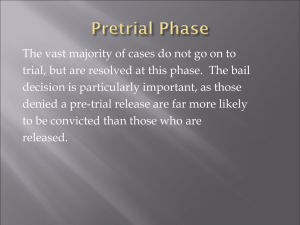

Topic: Bail Introduction When a person was charged with a crime before a court and held in police custody, the accused will be brought to the court for the court to decide whether they should continue to be held in custody or be released by bail. All crimes and offences except the unbailable offence are bailable in nature. However, bail must be refused if the court found that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the accused has been guilty of an offense punishable by death or life imprisonment. If the offence committed by the accused was a bailable offence, the court must release the accused as of rights. The court may also impose certain conditions in granting a bail to the accused, for example having the accused to surrender his passport or any diplomatic identification. Failure to comply with the required conditions imposed on the accused may lead the accused being kept in remand until trial. When there is a lawyer represent the accused, the lawyer will request the court to release the accused on bail whereas an unrepresented accused will be on the discretion of the court to decide whether to grant a bail to the accused. Bails can also be considered as a bond between the accused and the court by paying a certain sum of money for the purpose of securing attendance. The court will also request a bailor or guarantee to enter into a recognisance to ensure that if the accused break the conditions of bail, they will have to bare the responsibilities and consequences. 1.0 Definition of Bail General Rule: The giving of bail is to restore a person to his freedom, yet technically he is considered as being delivered into the custody of his sureties, who have control and dominion over him. The sureties will act as an administrator of the accused to ensure the appearance of the accused and pay the cost of the bail payment on behalf of the accused. Bail is also considered as a temporary released of an accused person upon paying a certain sum of securities to the court and an undertaking by the bailor to ensure the attendance of the accused throughout his trial. According to Blackstone’s Commentaries, it defines bail as delivery or bailment of a person to his sureties, upon their giving (together with himself) sufficient security for his appearance: he being supposed to continue in their friendly custody, instead of going to gaol.’ Tomlins Law Dictionary defines bail as to set liberty of an arrested person by taking security for his appearance at a specific day and place determined by the court. The reason why it is called a bail is to bind the accused and his sureties for his forthcoming and render the accused from going into the prison. In Termes de la Ley, it was provided that an arrested man who was restrained of his liberty or being by law bailable, the law offered the accused to be released by bail with the conditions that a certain sum of money will be bound by the accused and sureties to ensure the appearance of the accused. Upon the bonds of these sureties, it is said that the accused is bailed, that is to say, set the accused at liberty until the day appointed for his appearance determine by the court. Chapter 38 of the Criminal Procedure Code provide a comprehensive guideline and procedure in respect of bail. Bail means to set aside at liberty for an arrested person, on surety to secure for his appearance during the trial. It is also said to give the accused the right to be released from custody granted to a person charged with an offence on condition that he or she undertakes to return to court at some specified time and any other condition that the court may impose. R v Light : The accused had a prima facie right to be at liberty until conviction which is consistent with the principle of every accused person of a crime is presumed to be innocent until proved guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. However, this right may be regulated by statutory requirement on the rights of release on bail. In Mallal’s Criminal Procedure, 4th Ed, at 461, it was stated that bail should not be refused on the basis that the accused have been punishable to a long term of imprisonment or that the granting of bail has a tendency to increase the number of appeals and of protracting the appellate proceedings. The discretion vested in the hand of the Court to grant bail should be judiciously exercised in accordance with the principles laid down by the Statutes on the facts of each particular case. 2.0 Purpose of Bail R v Rose: Bail is not punitive in nature. Bail should not be withheld as a punishment, the only purpose in giving out bail is to secure the attendance of the prisoner at the trial. This was affirmed in the case of Moh Ting King v PP and Mohd Jalil bin Abdullah v PP. Yusof bin Mohamed v PP: Bail, in his literal meaning means security taken from a person to appear on a fixed date before a court. However, bail is not granted automatically as to safeguard the society from the hazard of the misadventures of one who has been alleged to have committed a crime. See Section 389 3.0 Types of Bail When there is a trial or a pending appeal, the court may grant a bail to the accused pending the trial or appeal. Whether or not bail will be granted is depend on the discretion of the court and the nature of the offences committed by the accused. A matter of bail if determined on the ground whether the accused was charged with a bailable or a non- bailable offence. The general principle of law relating to bail will be governed under Section 387 to 394 of the Criminal Procedure Code. A. Bailable Offences Section 2 CPC: Offence shown as bailable in the First Schedule or which is made bailable by any other law for the time being in force Section 387 CPC: Any person except non-bailable offenders is arrested or detained without warrant shall release him on bail, provided that he is prepared to give bail Bailable offence will be usually granted by the court as of rights as stated under s387. The sentence for the offence committed by the accused will be relatively less serious and carry a lesser punishment as well. B. Non-Bailable Offences Section 2 CPC: Non bailable offence means any other offence than a bailable offence Section 388: Any person committed a non bailable offence will be released on bail except the court found that there appears reasonable grounds for believing that he has been guilty of an offence punishable with death or imprisonment for life. The term ‘non-bailable’ is not equivalent to the term ‘unbailable’ where bail is prohibited absolutely. The court is given a complete discretion under section 388 to decide whether to allow bail in the case of a non-bailable offence. C. Unbailable Offences There is specific provision in a written law stating that bail shall not be granted to an accused person who is charged with a particular offence notwithstanding any written law or any rule of law to the contrary Bail will not be granted at all by the court Section 12 (1) of the Firearms (Increased penalties) Act 1971: Bail shall not be granted to an accused person charged with an offence under this Act. Section 41B of the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952: Bail shall not be granted to an accused charged with an offence under this Act where the offence is punishable with death or imprisonment more than five years or less than five years but PP certifies in his writing that it is not in the public interest to grant bail to the accused. Section 57(4) of the Internal Security Act 1960: A person charged with an offence against this section shall not be granted bail. R9 of ESCAR: Bail shall not be granted to an accused person in a security case, but it may be allowed where the offence is not punishable with death/ life imprisonment if the accused satisfies the court that he should be granted bail. Yap Sooi Kim v PP: “Punishable with imprisonment” as stated under Section 41B(1)(b) DDA means the powers of punishment that the court has under the law, not the punishment which the court choose to impose. Accused charged with Section 39A(2) which impose imprisonment for life with minimum 5 years imprisonment, lies within the ambit of S.41B(1)(b). Lay Chin Hei v PP: Provision of specific law prevail provision of general law. PP v Chiew Siew Luan: Provision regarding the granting of bail should be construed in the context of the DDA, not in the CPC and to the extent that the general provision of CPC must be ex necessitate yield to specific provisions of S.41B DDA. Generalibus Specilia Derogant: when a special provision is made in a special statute, that special provision excludes operation of general law. PP v Ilamaran: Section 41B DDA override Section 388 CPC D. Bail Pending Investigation In normal context, the police are allowed to arrest and hold the arrested person in custody for a maximum of 48 hours without bail. However, the police have to release the accused at the end of the 48 hours if there are insufficient evidence to charge and remand the accused. If the police decide to hold the accused, the case will be passed to the prosecutor and the court will decide on whether to grant bail on the accused. If it is a bailable offence, the court will set the bail amount and release the accused as of rights. The accused may be released on bail during the police investigation if he is not produced before the magistrate within 24 hours and the said investigation is still ongoing. The accused was given the right to be released on bail under Article 5(4) of the Federal constitution and Section 28 of the CPC because the police has no sufficient ground to charge the accused. However, this doesn’t mean that the accused are totally free from the charges or offense because the police are still suspicious that the accused have committed a criminal offence. Typically what happens is that you are interviewed under caution by the police, but there are not sufficient grounds to charge you. However, the police do not want to dismiss you as a suspect just yet. Instead, they want more time to make inquiries, before deciding whether or not to refer your case to the Public Prosecutor. The police, therefore, choose to release you under investigation. This allows you to leave the police station, but the police can seize your personal property as evidence. The accused will be protected under Section 29 CPC, section 387 and 388 CPC. Section 29: “No person who has been arrested by a police officer shall be released except on his own bond or on bail or under the order in writing of a Magistrate or of a police officer not below the rank of Inspector.” Section 387 - Applies to bailable offences - A police officer (Officer in Charge of Police Station or any Police Officer not under the rank of corporal) shall release an accused who had committed a bailable offence on bail or discharge him on executing a bond (personal bond) without sureties pending investigation. This is sometimes referred to as “police bail”. Section 388 - Applies to non-bailable offences - A police officer in charge of the police district (OCPD) shall release an accused who had committed a non-bailable offence on bail pending investigation but he shall not be so released if there appears reasonable grounds for believing that he has been guilty of an offence punishable with death or imprisonment for life. - The police officer is also allowed to exercise his discretion to release an accused who had committed a non-bailable offence on bail at any stage of the investigation with a condition that the accused execute a bond (personal bond) without sureties to secure his attendance when required. - This is subject to the condition that there are not reasonable grounds for believing that the accused has committed a non-bailable offence, but there are sufficient grounds for further inquiry into his guilt by the Court, thus pending such inquiry the accused shall be released on bail pending investigation. - Pursuant to section 388 (3) CPC, the officer shall record in writing the reasons for releasing the accused on bail pending investigation. However, the right to bail pending investigation will be vested at the discretion of the Magistrate court to remand the accused in custody pending completion of police investigation pursuant to section 117 CPC. Maja anak Kus v PP : - The appellant submitted that when a person is brought before a magistrate accused of a bailable offence, even under section 117, Criminal Procedure Code for further remand, he is entitled to bail as of right, provided he is able and willing to furnish bail; and section 117 comes into operation after the person is arrested under section 28 and investigation cannot be completed within 24 hours. It was emphasized that section 28 clearly stipulates that the arrest and detention is subject to the provisions in the Code as to bail. Although he is brought before a magistrate under section 117, his right to bail remains, and the magistrate is bound to grant him bail under section 387(i) if he is arrested for a bailable offence and is prepared to give bail. - It was held that Section117 overrides the right to bail under Section 387. Magistrate was right to refuse bail and ordered for the remand of the accused under Section117 for police investigation. - (In short, the court has the discretion to grant the bail or refuse the bail even though Section 387 allows the accused who was committed a bailable offence to be release on bail as of rights. The court will see the nature and the merits of the case then decide on whether to grant or reject the application of bail) E. Bail Pending Trial An accused may be released on bail during pending trial subject to the type of offence for which he was charged in the court. The issuance of bail or bond will be done when the accused is charged in court. Bail pending trial is when the accused was officially charged and claim trial in the court and the court will fix a date for the hearing of the trial. While waiting for the pending date of the trial, the accused will request to be released on bail during the trial. If an accused is released on bail pending trial, he may have to obtain sureties to secure his attendance in court when required (at the date (s) of hearing/trial). Further the court may impose other conditions like the number of sureties required to secure his release on bail, amount of bond the surety has to deposit as security with the court as well as other conditions like for the accused to surrender all his travel documents to court. (*) The accused will be given during the pending trial either to be release on bail with two sureties or to be release on personal bond. For the accused to be release on bail with two sureties, the court may impose certain conditions under Section 390 whereas for the accused to be released on personal bond, it is a bond executed by the accused himself as a promise/guarantee that he will appear in court as and when required by it. We can see under section 387 (2), 388 (2), 390 (1) CPC 4.0 Principle of Bail The underlying principle of the bail is that an arrested person should be release on bail as to their rights except certain circumstances where the court found reasonable grounds that the accused had committed with the offence punishable with death or life imprisonment. This relates to the principle that an accused is presumed innocent until proven guilty. We can see in the case of R v Lim Kwang Seng where the court held that any accused person committed bailable offence and who is prepared to give bail must be released on bail. In Malaysia, there are differing opinions as to whether bail may be revoked or cancelled, and the accused committed into custody. In Mohd Jalil bin Abdullah v PP, after repeated absences from the hearings, the Magistrate issued warrants for the arrest of the accused persons who were on bail, revoked their bail, committed them to custody, set a new date for the hearing of the case and dismissed their application for bail. On their application to the High Court, the court held that the Magistrate was wrong when he ordered the accused persons to be remanded; what the Magistrate should have done was, upon revocation of the bail, grant the accused persons a new bail with sufficient sureties as he deemed fit. Only if they failed to execute the fresh bail, would the Magistrate be empowered to commit both the accused to custody. In the case of Wong Kim Woon v PP, the court decided that where there has been a breach of fundamental term of the bail, there cannot be any other consequence consistent with due administration of justice than that bail be ended, whether by revocation or cancellation. The revocation or cancellation cannot amount to an exercise of an inherent jurisdiction. In such a case, there will be no contravention of Section 387(1) since bail has been granted, and a cancellation or revocation will merely be a consequence of breach of its terms. Specific statutory power to cancel or revoke bail in such circumstances is unnecessary PP v Dato Mat: Where discretion is given to the court to either refuse or grant bail, that discretion in itself implies a discretion to grant bail subject to certain conditions. Thus, it follows that where no such discretion is given, there is no power to impose conditions in the order granting bail. (It is the discretion of the court to grant bail to the accused but subject to certain conditions. However, the court cannot impose further conditions for bailable offence as this is the right of the accused.) For non-bailable offence, the accused did not has the right to be released on bail but bail is allowed subject to the discretion of the court. This can be seen in Section 388. Under Section 388, if the accused was charged with a non bailable offence and the court found that he has the reasonable ground to believe that the accused committed offence punishable with death or life imprisonment, the court will not release the accused on bail. However, if the accused committed a non bailable offence but the court has no reasonable ground to believe that the accused committed offence punishable with death or life imprisonment, the court will subject to his discretion release the accused on bail. However, there are also three categories where the court may grant bail to the accused who was charged for offences punishable with death or imprisonment for life and it appears there are reasonable grounds for believing that the accused is guilty of the offence. Women - PP v Latchemy: The female accused was charged for murder and released on bail of RM 2,000 on the ground that she was a mother of 10 children and was breast feeding. However, the high court revoked the grant of bail because the reason was not exceptional and special reason - Leow Nyuk Chin v PP : The female accused was charged with the offence of murder under Section 302 of the Penal Code. The accused’s counsel relied on the accused being a women and tendered a medical report on her health condition - Che Su bt Daud v PP : The female accused was jointly charged with her husband for drug trafficking. She relied on the ground that she was a mother of six children and was breast feeding the youngest children. The High court , agreed with Latchemy case that her reason was not exception or special reason. Minor under the age of 16 years old - KWK (A Child) v PP : The accused was 12 years old at the time of commission of offence, the bail will only be given in exceptional circumstances. Sick or infirm person - PP v Dato Balwant Singh: The court granted bail in the sum of RM 500,000 to the accused under the provision of Section 388 with two sureties as he was above 80 years old and had various medical conditions. Other relevant factors (Mallal’s Criminal Procedure Code) - The nature and gravity of the offence charged; - The nature of the evidence in support of the charge; - Whether there is or is not reasonable grounds for believing the accused is guilty of the offence; - The severity and degree of punishment which conviction might entail; - The guarantee that the accused, if released on bail, will not either abscond or obstruct the prosecution in any way; - The danger of the offence being continued or repeated; - The danger of the witnesses being tampered with; - Whether the accused if released on bail, is likely to tamper with the prosecution evidence; - Whether the accused is likely to get up false evidence in support of the defense; - The opportunity of the accused to prepare the defense; - The character, means and standing of the accused; - The long period of detention of the accused and probability of further period of delay. - Also can referred to the case of PP v Wee See Siang where the court also listed 9 factors similar to the factors referred to above and added that the list is not exhaustive. - Che Su bt Daud v PP : These factors are not exhaustive, thus, factors such as age, sex and state of health of the accused are relevant factors to be considered - Dato’ Seri Anwar Ibrahim v PP: The court held that the critical factor is that applicants must show reasonably to the satisfaction of the court that their cases come within the ‘exceptional circumstances’ category. In this case, the medical condition of the first applicant did not meet the test of ‘exceptional circumstances’ as to warrant the grant of bail as there was no assertion or any medical evidence produced to show that the continuous incarceration of the first applicant was the cause of his further injuries as alleged. 5.0 Objection to Bail Bail may be opposed on the ground that the court has a reasonable ground to believe that the accused had committed with offence punishable with life imprisonment or death. Bail may also be opposed by the court on certain reason, for example the if granted bail will tamper with potential witnesses that may directly implicate the accused is considered in the case of Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim v PP. The said witnesses made police reports to that effect. In the case of Shaikh Karim & Ors v Emperor AIR, the court held that the status of an accused person is not a sufficient ground for granting an application for bail. The respectability of an accused person per se is not sufficient for him being admitted for bail nor does his bad character disentitle him to get bail. 6.0 Conditions that can be imposed For non-bailable offence, the court may grant bail to the accused but subject to certain conditions. PP v Dato Mat : The court stated that where discretion is given to the court to either refuse or grant bail, that discretion in itself implies a discretion to grant bail subject to certain conditions. - The respondent was charged for a non bailable offence under Section 409 of the Penal Code. The judge release the respondent on bail bond in two sureties and on condition that he surrendered his international passport to the court. - The law relating to bail is set out in Chapter XXXV of the Criminal Procedure Code. Section 387 sets out the right of an accused or arrested person to bail in bailable offence. Section 388 provides for the circumstances where a police officer or the court may exercise its discretion to release on bail any person accused of a non-bailable offence. Both sections do not have any specific provision for the imposition of conditions. - However, Indian authorities seem to favour the view that when discretion is given to the court to refuse or grant bail, that discretion in itself implies a discretion to grant bail subject to certain conditions. But, when there is no discretion to refuse bail, the question of imposing conditions does not arise — Rex v Genda Singh & Ors AIR 1950 All 525. Thus conditions can be included in a bail bond issued pursuant to s 388 but not to s 387 as the latter section gives no discretion to the officer or court to withold bail when the person arrested is prepared to provide such bail. - In Varadaraja Mavalliar (1957) 1 Mad LJ (Crim) 717, the Madras High Court reviewing the case law on this subject held that in non-bailable offences, the court can impose restriction in suitable cases. In Re Kota Appalakonda AIR 1942 Mal 749 the court in holding that condition made under s 496 of the Indian Criminal Procedure Code to be invalid made the following observation on the scope of s 497: With regard to non-bailable offences, I can see no objection to imposing conditions of this kind; for the magistrate has an option to grant bail or to refuse bail and he has also the power under s 497(5) of the Criminal Procedure Code of causing persons so released to be arrested and committed to custody, which subsection he would apply in case the condition was not fulfilled. - The provisions of s 496, s 497 and s 498 of the former Indian Criminal Procedure Code correspond with s 387, s 388 and s 389 respectively of our Criminal Procedure Code and for the same reasons as expressed in the aforementioned case, we would agree that analogous fair and reasonable conditions apropos to the securing of the accused's subsequent attendence in court are not illegal and therefore imposable by our courts. In fact, although no ruling was made in the Federal Court's decision in Government of Malaysia & Ors v Loh Wai Kong [1979] 2 MLJ 33and the Supreme Court's decision in PP v Zulkifflee bin Hassan [1990] 2 MLJ 215 the facts in both cases clearly indicate that the condition for the surrender of passport was not disapproved of by the court. PP v Abdul Rahim bin Hj Ahmad : Other than requiring the surrender of passports as a condition to bail, the court is empowered to impose different types of conditions to bail. (where two conditions of bail were imposed in that the applicants were required to report twice a day to the nearest police station and were not to approach the premises where the complainant lived). PP v Dato’ Balwant Singh: The court has granted the accused with a sum of RM 500,000 bail with two sureties with security to be furnished and several conditions which included To surrender firearm and license to the police; to remain indoors for a stipulated time. When the court impose conditions to the granting of bail, the accused must strictly comply with it, otherwise the accused will face the risk of being remanded in custody pending trial. Dato Mat case : The practice to do so however had gained judicial recognition in the courts in both India and Malaysia on the rationale that such condition would provide an adjunctive or supplemental security towards ensuring the attendance of the arrested person at his subsequent trial. No person can be admitted to bail under s 388 or s 389 purely on his undertaking to abide by some conditions alone without binding himself to forfeit a certain sum in the event of his default, but a person may be released on bail without any condition attached to it. Such condition therefore, to our mind, is not the principal but only a complementary security to be applied concomitantly with the amount prescribed in the bail bond. Such condition in the bail bond would have a persuasive effect of reducing a larger amount of bail which would have been otherwise required by the court. To put it in another way — a court may require a certain large amount to be deposited in respect of a non bailable offence but would be willing to reduce it to a lesser sum on the undertaking of the detained person to surrender his passport. 6.0 Application For Bail If the application for bail made by the accused was refused by any inferior court, the accused may appeal to the high court, which may confirm, vary or reverse the order of the inferior court. The accused may make an appeal to the High Court under Section 394. The high court will determine the merit of the case and the decision made by the inferior court, confirm, vary or reverse the order made by such inferior court or apply to the High court under Section 389 whereupon the High Court may grant or vary bail, though it cannot order custody if bail has been granted at first instance In the case of Sulaiman bin Kadir v PP, the applicant was charged with rape under Section 376 of the Penal Code. The applicant applied for bail pending trial but was refused by the Session court under Section 388. The Deputy Public Prosecutor contended that the the application is in effect an appeal from the refusal of the learned president to grant bail and that therefore these proceedings should be brought by Notice of Appeal under section 394 of the Criminal Procedure Code which reads: "Any person aggrieved by any order or refusal of any inferior court made under this chapter may appeal to the High Court, which may confirm, vary or reverse the order of such inferior court." - The difference between the two procedures is simply this: If it is an appeal, it will take a longer time to be heard because there has to be a Notice of Appeal and the Subordinate Court will have to state its reasons for refusal before the Petition of Appeal can be filed and eventually heard but if it is an application by Notice of Motion supported by affidavit, it can be made immediately after refusal without notice to the Subordinate Court (but with Notice to the Public Prosecutor) and the application can even be heard by the High Court on the same day or very soon thereafter, speed being the essence of such an application. - There does not appear to be any authority as to which is the proper course to take in such cases. In my view, if a person should not be kept in custody for a moment longer than is necessary then the speedy procedure of section 389 is obviously indicated. But there are other compelling reasons why section 389 is the appropriate procedure. That section gives the High Court absolute discretionary powers to vary bail from time of arrest right up to the time of conviction. It may grant bail when bail has been refused. It may reduce the amount of bail if the amount is excessive. It may increase the amount of bail if the amount is insufficient. But it may not order custody if bail has been granted. - The appeal provisions of section 394 of the Criminal Procedure Code, on the other hand, are intended to deal with matters not provided for under section 389 of the Criminal Procedure Code, for instance, if an accused person had been admitted to bail by a Subordinate Court contrary to section 388(i) of the Criminal Procedure Code. As this application arises out of a refusal to grant bail, the provisions of section 389 apply and I accordingly hold thatit is properly before this court. PP v Chew Siew Luan: Fresh application may be made to the High Court if attempt made at the lower court failed. The appeal provisions in s 394 are therefore intended to deal with matters not provided for under s 389, such as for instance, where an accused person has been admitted to bail by an inferior court contrary to s 388(1). It appears that orders and refusals of police officers concerning bail are not appealable under s 394 since the term ‘police officers’ is not included in the section. In such a case, an application may be made under s 389 wherein the High Court may, inter alia, direct any person be admitted to bail, reduce or increase the bail required by a police officer or court. Where a person’s application for bail is rejected the first time, he may apply again to the same court and if there has been a change of circumstances since the last unsuccessful attempt, bail may be granted PP v Abdul Rahim bin Hj Ahmad : The three applicants were arrested and charged with the offence of rape. They were released on bail but were subsequently re-arrested. They applied for bail twice but their applications were refused. This is their third application for bail. In this application, counsel for the applicants pleaded that (a) there had been a change of circumstances since the two unsuccessful applications were heard in that there was now available to the court a medical report showing that the complainant may not have been raped at all; (b) the preliminary inquiry for the case had been delayed for a further six weeks and the applicants had already been in custody for a considerable time (about four months since the date of their re-arrest). - The court allow the bail application and impose certain conditions that the applicants should report once in the morning and once in the evening to the nearest police station and that they do not approach near the premises where the complainant lives. Michael Lee @ Weng Onn Lee v PP: The court held that there can be fresh application for bail when there was material changes un circumstances which was not considered in earlier application. It must also be noted that when bail is not granted by the subordinate court, an application can be made directly to the high court under Section 389. There is actually no necessity to rely on Section 394 procedure as it will take a longer time and procedure for the accused to appeal for the application of bail. Section 389 need not required for fresh application for bail to be made to the high court when there is a change of circumstances. The only requirement by the applicant/accused is to show to the court that there has to be an alteration or variation of the bail order made. The alteration or variation can be on the refusal of bail by the court or conditions of bail set by the court. The applicant/accused has only to show sufficient and cogent reasons like material change in circumstances since the last order made by the court or new facts have come to light which the court ought to know. E.g. there is now available to the court in a rape case information on the proposed marriage of the accused to the victim of rape. Section 389 : Fast and speedy Section 394: The process of appeal is cumbersome as it entails filing of a Notice of Appeal, to wait for the grounds of decision of the lower court judge, filing of a petition of appeal premised on the grounds furnished and to wait for a hearing date of appeal by high court. The entire process is slow and it will defeat the urgent nature of the subject matter which is bail. In a situation where an accused has not been granted bail, he may have to be remanded in custody pending an appeal pursuant to section 394 CPC. - An appeal under s 394 involves a long and tedious process. The process of appeal first involves filing a notice of appeal within 14 days from the time of the order appealed from is passed or made Upon filing the notice of appeal, the appellant has to wait for the court appealed from to make and serve him a signed copy of the grounds of decision. The preparation of the grounds of judgment often takes a long time as illustrate in the case of Voon Chin Fatt v PP where the court held that the grounds of decision should always be written as promptly as possible. However this is not often the case: see TN Nathan v PP[1978] 2 MLJ 134), as a result of which the accused may be unnecessarily detained. Thus, it is clear that where an accused is denied bail, an appeal under s 394 would not be a good option: see PP v Dato’ Mat[1991] 2 MLJ 186, SC. In contrast, the procedure under s 389 is simpler and quicker: see Sulaiman bin Kadir v PP[1976] 2 MLJ 37, where Harun J explained the differences between the two procedures in the following words: ‘The difference between the two procedures is simply this: If it is an appeal, it will take a longer time to be heard because there has to be a Notice of Appeal and the Subordinate Court will have to state its reasons for refusal before the Petition of Appeal can be filed and eventually heard but if it is an application by Notice of Motion supported by affidavit, it can be made immediately after refusal without notice to the Subordinate Court (but with Notice to the Public Prosecutor) and the application can even be heard by the High Court on the same day or very soon thereafter, speed being the essence of such an application. - There does not appear to be any authority as to which is the proper course to take in such cases. In my view, if a person should not be kept in custody for a moment longer than is necessary then the speedy procedure of section 389 is obviously indicated. But there are other compelling reasons why section 389 is the appropriate procedure. That section gives the High Court absolute discretionary powers to vary bail from time of arrest right up to the time of conviction. It may grant bail when bail has been refused. It may reduce the amount of bail if the amount is excessive. It may increase the amount of bail if the amount is insufficient. But it may not order custody if bail has been granted. - The appeal provisions of section 394 of the Criminal Procedure Code, on the other hand, are intended to deal with matters not provided for under section 389 of the Criminal Procedure Code, for instance, if an accused person had been admitted to bail by a Subordinate Court contrary to section 388(1) of the Criminal Procedure Code. As this application arises out of a refusal to grant bail, the provisions of section 389 apply and I accordingly hold that it is properly before this court.’ In PP v Zulkifflee bin Hassan, the court held that the High Court has jurisdiction to entertain an application under s 389 concerning the amount of bond executed, even though no appeal was filed under s 394. Soo Shiok Liong v Pendakwa Raya : The court held that the amount of bail shall not be excessive but be reasonable based on the circumstances of the case. - Bail is never designed to be punitive in nature against the applicant; it is merely to warrant appearance of the applicant at the place, date and time stated in the bond. Therefore, quantum of bail should be reasonable and non excessive, failing which it will defeat the purpose of bail, in the event the Court is prepared to release him on bail. If the amount of bail is excessive, it might caused difficulties to the applicant in getting suitable sureties to post bail as fixed by the court, especially for a person of ‘meagre means’ - An excessive bail amount has the effect of punishing the accused even before he is found guilty of the offence for which he is charged with. The bail amount alone cannot be the sole consideration to ensure the attendance of the accused in court. In fixing the amount of bail the court has to take into consideration the circumstances of each particular case, such as for instance, whether the accused has co-operated with the police in their investigations and whether the accused has benefited from the fruits of his crime. - The court in this case has laid down several factors for consideration in setting the quantum of bail bond as follows, which however is not exhaustive: 1. The nature and gravity of the offence and the severity and degree of punishment which conviction might entail; One of the relevant, but not overriding factors to be considered; 2. The quantum should be higher in the case of non-bailable offences; 3. An excessive quantum may defeat the granting of bail; 4. Whether there is a likelihood of the applicant absconding if the bail quantum is set at too low; 5. Bail is not intended to be punitive but only to secure the attendance of the Accused at the trial therefore that amount of the bond must be fixed with the regard to the circumstances and must not be excessive; 6. Conditions set in granting the bail such as surrender of traveling documents should also be taken into consideration in reducing the quantum of bail; 7. Cooperation given by the Accused should also go to abate the quantum of bail; 8. The quantum of bail should not be set so prohibitively high as to have the effect of incarcerating the Accused before he is convicted of the crime; and 9. Factors for consideration in setting the quantum of bail bond-application of the Court’s mind in considering such factors to be reflected in the judge’s records. - The Court should be prepared to grant bail, as the denial of bail has the effect of punishing an accused before he is proven guilty of the charges against him, where he may be kept under remand for months, even years before the completion of the trial, where at the end of the trial he may be found to be not guilty and subsequently acquitted. This is against the cardinal principle and basis of criminal law that is ‘presumed to be innocent until proven guilty’. A quantum of bail which is excessive results in the inability of the accused to post bail which has the same effect, as the accused may find difficulty in securing a bailor acceptable by the court posting bail on the amount fixed. - Bail should only be refused when there are reasons to believe or there are allegations made that if bail is granted, the applicant may abscond or obstruct the prosecution in any way; there is danger that the offence will continue or repeated; there is danger of witness or the prosecution evidence being tampered with. However, mere allegation of the same is not sufficient and there must be some information or evidence on record indicating the possibility. - The court in this case has expressed his beliefs against the deprivation of ones liberty until proven guilty. Justice must not only be done but must be seen to be done. * The amount of every bond executed under the provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code relating to bail must be fixed with due regard to the circumstances of the case as being sufficient to secure the attendance of the person arrested, but may not be excessive, and a Judge4may, in any case, whether there be an appeal on conviction or not, direct that any person be admitted to bail or that the bail required by a police officer or Court be reduced or increased. 7.0 Revocation of Bail Section 388 (5): gives power to the court to revoke or cancel a bail if there is an infringement of the terms of bail. The rationale behind the cancellation of bail is that since bail under s 388(1) is a privilege and not a right, it may be cancelled if the accused abuses his pre-trial liberty The procedure to be followed in cancelling or revoking bail is not provided for by the Criminal Procedure Code, however, it appears that there must be some form of evidence to support the application for revocation or cancellation but mere vague allegations would not be sufficient Phang Yong Fook v PP : In the present case, the learned Deputy only made vague allegations of harassment, tampering and intimidation in support of his application to revoke the bail in the court below. There was no oral or documentary evidences or even an affidavit to support the allegations. Wong Kim Woon v PP: it was decided that where there has been a breach of that fundamental term of the bail, there cannot be any other consequence consistent with due administration of justice than that bail be ended, whether by revocation or cancellation. The revocation or cancellation cannot amount to an exercise of an inherent jurisdiction. In such a case, there will be no contravention of s 387(1) since bail has been granted, and a cancellation or revocation will merely be a consequence of breach of its terms. Specific statutory power to cancel or revoke bail in such circumstances is unnecessary. - Application for revocation must be supported with reasons. - The reasons has to be with merits, for the accused to be remanded pending trial; e.g. harassing and tampering with witnesses. - The allegations against the accused must be supported by oral or documentary evidence. This will be contained in the affidavit in support of application for revocation of bail by the prosecution. - Ultimately the court must allow the accused an opportunity to be heard before bail is revoked; the principle of natural justice which is audi alteram partum. 8.0 Forfeiture of bond When an accused is released on bail or personal bond, he has to ensure appearance at the specified court on the required date and time. [s390] If he is released on bail his surety or sureties has to ensure his appearance in court. If the accused failed to appear or if the terms or conditions of a bond is breached the court may forfeit the sum of money deposited for the bond. If the accused who is released on bail or bond pending trial is absent in court on the required date and time, the court will issue a warrant of arrest against him followed by a Notice to Show Cause to the surety/bailor as to why the bond should not be forfeited. PROCEDURE TO FORFEIT S.404 Khor Ewe Suan o The court lay down the guideline on the procedure of S.404(1) - Whenever the bond is for appearance before a court and it is proved to the satisfaction of that court that such bond has been forfeited, the court shall record the grounds of such proof and may call upon any person bound by such bond to pay the penalty or to show cause why it should not be paid. [s404(1)] - The court first to take evidence about the bond and the sureties. This evidence may be given by specific witnesses, i.e. magistrates, SC judge or registrar who granted bail The sureties will be given opportunity to cross examine those witnesses If sufficient cause is not shown and the penalty is not paid, the court may proceed to recover the same by issuing a warrant for attachment and sale of property belonging to that person. [s404(2)] If the penalty is not paid and cannot be recovered by such attachment and sale, the person so bound shall be liable to imprisonment which may extend to six months. [s404(4)] The court has a discretion to remit any portion of the penalty and enforce payment in part only. [s404(5)] All forfeiture orders are appealable to the High Court pursuant to section 405 CPC. If the procedure is not complied with the court on appeal may set aside the forfeiture. All forfeiture orders are appealable to the High Court pursuant to section 405 CPC. CASES: Valliamai v PP o Mother in law stood surety to son in law. The order for forfeiture was set aside as sufficient cause had been shown. Ramlee & Anor o There were 2 bailor who had their RM2000 bail forfeited. They appealed. The learned judge was satisfied that the appellants had taken all steps to ensure the presence of the OKT in court. Sufficient cause was shown and the order to forfeit was quashed. Khor Hong Guan o Both the appellants had stood surety for the OKT to appear before a Magistrate Court. OKT had appeared several times until the case was transferred to the Sessions Court where the OKT was absent o Appellants submitted that their duty was to ensure the OKT to appear in Magistrate Court and not Sessions Court. The court held that they have not contravened the condition of their bonds and therefore the forfeiture should be set aside.