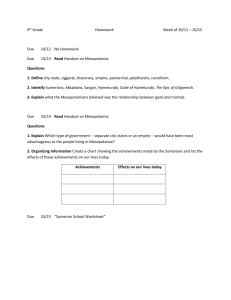

Mesopotamia Mesopotamia is a region of southwest Asia in the Tigris and Euphrates river system that benefitted from the area’s climate and geography to host the beginnings of human civilization. Its history is marked by many important inventions that changed the world, including the concept of time, math, the wheel, sailboats, maps and writing. Mesopotamia is also defined by a changing succession of ruling bodies from different areas and cities that seized control over a period of thousands of years. I. City-states - Sumer grew rapidly. Soon, there were hundreds of villages and towns, some with populations of only a few hundred and some with populations of 30,000 or more. Cities became the centers of trade, learning, and religion and offered people more opportunities than life in the country. By the year 2500 BCE, the total population in ancient Sumer was more than half a million people. About four out of five of those people lived in the cities, making Sumer the world’s first urban culture. To protect themselves, small towns attached themselves to big cities. This created a system of city-states. City-states are communities that include a city and its nearby farmland. The nearby land might include several smaller villages. There were many city-states throughout Sumer. Some of the most powerful city-states included Eridu, Bad-tibura, Shuruppak, Uruk, Sippar, and Ur. Eridu is thought to be the first of the major cities formed and one of the oldest cities in the world. - Each city-state had its own ruler. They went by various titles such as lugal, en, or ensi. The ruler was like a king or governor. The ruler of the city was often the high priest of their religion as well. This gave him even more power. The most famous king was Gilgamesh of Uruk who was the subject of the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the world's oldest surviving works of literature. In addition to the king or governor, there was a fairly complex government with officials who helped to organize city building projects and keep the city running. There were also laws that the citizens must follow or face punishment. The invention of government is often credited to the Sumerians. II. Empires of Ancient Mesopotamia 1. Akkadian Empire - The Akkadian Empire was an ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia, which united all the indigenous Akkadian speaking Semites and the Sumerian speakers under one rule within a multilingual empire. - King Sargon, the founder of the empire, conquered several regions in Mesopotamia and consolidated his power by instating Akaddian officials in new territories. He extended trade across Mesopotamia and strengthened the economy through rain-fed agriculture in northern Mesopotamia. - The Akkadian Empire experienced a period of successful conquest under Naram-Sin due to benign climatic conditions, huge agricultural surpluses, and the confiscation of wealth. - The empire collapsed after the invasion of the Gutians. Changing climatic conditions also contributed to internal rivalries and fragmentation, and the empire eventually split into the Assyrian Empire in the north and the Babylonian empire in the south. 2. Assyrian Empire - Assyria is named for its original capital, the ancient city of Ašur—also known as Ashur—in northern Mesopotamia. - Ashur was originally one of a number of Akkadian-speaking city states ruled by Sargon and his descendents during the Akkadian Empire. Within several hundred years of the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, Assyria had become a major empire. - At its peak, the Assyrian empire stretched from Cyprus in the Mediterranean Sea to Persia, and from the Caucasus Mountains (Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan) to the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt. It was at the height of technological, scientific, and cultural achievements for its time. - In the Old Assyrian period, Assyria established colonies in Asia Minor and the Levant, and asserted itself over southern Mesopotamia under king Ilushuma. - Assyria experienced fluctuating fortunes in the Middle Assyrian period, with some of its kings finding themselves under the influence of foreign rulers while others eclipsed neighboring empires. - Assyria became a great military power during the Neo-Assyrian period, and saw the conquests of large empires, such as Egyptians, the Phoenicians, the Hittites, and the Persians, among others. - After its fall in the late 600s BCE, Assyria remained a province and geo-political entity under various empires until the mid-7th century CE. 3. Babylon empire - A series of conflicts between the Amorites and the Assyrians followed the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, out of which Babylon arose as a powerful city-state c. 1894 BCE - Babylon remained a minor territory for a century after it was founded, until the reign of its sixth Amorite ruler, Hammurabi (1792-1750 BCE), an extremely efficient ruler who established a bureaucracy with taxation and centralized government. - Hammurabi also enjoyed various military successes over the whole of southern Mesopotamia, modern-day Iran and Syria, and the old Assyrian Empire in Asian Minor. - After the death of Hammurabi, the First Babylonian Dynasty eventually fell due to attacks from outside its borders. III. Cultural 1. Festival Ancient Mesopotamians had ceremonies each month. The theme of the rituals and festivals for each month was determined by at least six important factors: - The Lunar phase (a waxing moon meant abundance and growth, while a waning moon was associated with decline, conservation, and festivals of the Underworld) - The phase of the annual agricultural cycle - Equinoxes and solstices - The local mythos and its divine Patrons - The success of the reigning Monarch - The Akitu, or New Year Festival (First full moon after spring equinox) - Commemoration of specific historical events (founding, military victories, temple holidays, etc.) 2. Music Some songs were written for the gods but many were written to describe important events. Although music and songs amused kings, they were also enjoyed by ordinary people who liked to sing and dance in their homes or in the marketplaces. Songs were sung to children who passed them on to their children. Thus songs were passed on through many generations as an oral tradition until writing was more universal. These songs provided a means of passing on through the centuries highly important information about historical events 3. Games Hunting was popular among Assyrian kings. Boxing and wrestling feature frequently in art, and some form of polo was probably popular, with men sitting on the shoulders of other men rather than on horses. They also played majore, a game similar to the sport rugby, but played with a ball made of wood. They also played a board game similar to senet and backgammon, now known as the "Royal Game of Ur". 4. Family life Mesopotamia, as shown by successive law codes, those of Urukagina, Lipit Ishtar and Hammurabi, across its history became more and more a patriarchal society, one in which the men were far more powerful than the women. As for schooling, only royal offspring and sons of the rich and professionals, such as scribes, physicians, temple administrators, went to school. Most boys were taught their father's trade or were apprenticed out to learn a trade. Girls had to stay home with their mothers to learn housekeeping and cooking, and to look after the younger children. Some children would help with crushing grain or cleaning birds. Unusually for that time in history, women in Mesopotamia had rights. They could own property and, if they had good reason, get a divorce. 5. Burials Most people were buried in family graves under their houses, along with some possessions. A few have been found wrapped in mats and carpets. Deceased children were put in big "jars" which were placed in the family chapel. Other remains have been found buried in common city graveyards. IV. Code of Hammurabi The Code of Hammurabi was one of the earliest and most complete written legal codes and was proclaimed by the Babylonian king Hammurabi, who reigned from 1792 to 1750 B.C. Hammurabi expanded the city-state of Babylon along the Euphrates River to unite all of southern Mesopotamia. The Hammurabi code of laws, a collection of 282 rules, established standards for commercial interactions and set fines and punishments to meet the requirements of justice. Hammurabi’s Code was carved onto a massive, finger-shaped black stone stele (pillar) that was looted by invaders and finally rediscovered in 1901. 1. King Hammurabi - Hammurabi was the sixth king in the Babylonian dynasty, which ruled in central Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) from c. 1894 to 1595 B.C. - In the 30th year of his reign, Hammurabi began to expand his kingdom up and down the Tigris and Euphrates river valley, overthrowing the kingdoms of Assyria, Larsa, Eshunna and Mari until all of Mesopotamia was under his sway. 2. Code of Hammurabi - The Code of Hammurabi was one of the only sets of laws in the ancient Near East and also one of the first forms of law. The code of laws was arranged in orderly groups, so that all who read the laws would know what was required of them. Earlier collections of laws include the Code of Ur-Nammu, king of Ur (c. 2050 BC), the Laws of Eshnunna (c. 1930 BC) and the codex of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c. 1870 BC), while later ones include the Hittite laws, the Assyrian laws, and Mosaic Law. These codes originate from similar cultures in a relatively small geographical area, and they have passages that resemble each other - The Code of Hammurabi is the longest surviving text from the Old Babylonian period.[17] The code has been seen as an early example of a fundamental law, regulating a government – i.e., a primitive constitution.[18][19] The code is also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, and it also suggests that both the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence. - While the Code of Hammurabi was trying to achieve equality, biases still existed against those categorized in the lower end of the social spectrum and some of the punishments and justice could be gruesome. The magnitude of criminal penalties often was based on the identity and gender of both the person committing the crime and the victim. The Code issues justice following the three classes of Babylonian society: property owners, freed men, and slaves. - Punishments for someone assaulting someone from a lower class were far lighter than if they had assaulted someone of equal or higher status. For example, if a doctor killed a rich patient, he would have his hands cut off, but if he killed a slave, only financial restitution was required. Women could also receive punishments that their male counterparts would not, as men were permitted to have affairs with their servants and slaves, whereas married women would be harshly punished for committing adultery.