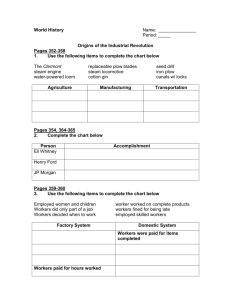

Despite the significant increases in productivity, the working conditions in the early cotton factories were atrocious o Adult weavers and spinners were reluctant to leave the safety and freedom of work in their own homes labor in noisy and dangerous factories where the air was filled with cotton fibers 16. Why did factory owners turn to children and foundlings for labor? Factory owners often turned to young orphans and children who had been abandoned by their parents and put in who had been abandoned by their parents and put in the care of local parishes Parish officers often apprenticed such unfortunate foundlings to factory owners; the parish thus saved money; the factory owners gained workers over whom they exercised almost the authority of slave owners Apprenticed as young as five or six years of age, boy and girl workers were forced by law to labor for their “masters” for as many as fourteen years 17. What were the working conditions for them? Housed, fed, and locked up nightly in factory dormitories, the young workers labored thirteen or fourteen hours a day for little or no pay Harsh physical punishment maintained brutal discipline; hours were appalling, commonly thirteens or fourteen hours a day, six days a week To be sure, poor children typically worked long hours in many types of demanding jobs, but this wholesale coercion of orphans as factory apprentices constituted exploitation on a truly unprecedented scale 18. Why was the creation of the world’s first machine powered factorings in the British textile industry in the 1770 and 1780s a major historical development? The creation of the world’s first machine-powered factories in the British cotton textile industry in the 1770s and 1780s, which grew out of the putting-out system of cottage production, was a major historical development Both symbolically and substantially, the big new cotton mills marked the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Britain By 1831 the largely mechanized cotton textile industry accounted for fully 22 percent of the country’s entire industrial production 19. Why was coal an alternative to wood? By the 18th century wood was in ever-shorter supply; processed wood (charcoal) was the fuel that was mixed with iron ore in the blast furnace to produce pig iron The iron industry’s appetite for wood was enormous, and by 1740 the Brian iron industry was stagnating; vast forests enabled Russia in the 18th century to become the world’s leading producer of iron, much of which was exported to Britain By 1640 most in London were heated with coal, and it was used in industry to provide heat for making beer, glass, soap, and other products; the breakthrough came when industrialists began to use coal to produce mechanical energy and to power machinery To produce more coal, mines had to be dug deeper and deeper and were constantly filling with water; mechanical pumps, usually powered by animals walking in circles at the surface, had to be installed 20. Why was the creation of the steam engine important for coal mining? Steam Engine: a breakthrough invention by Thomas Savery in 1698 and Thomas Newcomen in 1705 that burned coal to produce steam, which was then used to operate a pump; the early models were superseded by James Watt’s more efficient steam engine, patented in 1769 21. Why was the steam engine of Watt the most fundamental advance in society? In 1763 a gifted young Scot named James Watt was drawn to a critical study of the steam engine; Watt was employed at the time by the University of Glasgow as a skilled craftsman making scientific instruments A partnership in 1775 with Matthew Boulton, a wealthy English industrialist, provided Watt with adequate capital and exceptional skills in salesmanship that equaled those of the renowned pottery king, Josiah Wedgwood From ingenious manufactures such as the cannon maker John Wilkinson, Watt was gradually able to purchase precision parts; this support allowed him to create an effective vacuum in the condenser and regulate a complex engine By the late 1780s the firm of Boulton and Watt had made the steam engine a practical and commercial success in Britain For the first time in history, humanity had, at least for a few generations, almost unlimited power at its disposal; for the first time, inventors and engineers could devise and implement all kinds of power equipment to aid people in their work The steam engine drained mines and made possible the production of ever more coal to feed steam engines elsewhere The steam-power plant began to replace waterpower in cotton-spinning factories during the 1780s, contributing greatly to that industry’s phenomenal rise Steam took the place of waterpower in flour mills, in the malt mills used in breweries, in the flint mills supplying the pottery industry, and in the mills exported by Britain to the West Indies to crush sugarcane 22. What was coke and why was it important for iron? Originally, the smoke and fumes resulting from coal burning meant that coal could not be used as a cheap substitute for expensive charcoal in smelting iron Starting around 1710, ironmakers began to use coke, a smokeless and hot-burning fuel produced by heating coal to rid it of water and other impurities, to smelt pig iron After 1770 the adoption of steam-driven bellows in blast furnaces allowed for great increases in the quantity of pig iron produced by British ironmakers; in the 1780s Henry Cort developed the puddling furnace, which allowed pig iron to be refined in turn with coke Cort developed steam-powered rolling mills, which were capable of turning out finished iron in every shape and form; the economic consequence of these technical innovations was a great boom in the British iron industry o In 1740 annual British iron production was only 17,000 tons; with the spread of coke smelting and the impact of Cort’s inventions, production had reached 260,000 tons by 1806; in 1844 Britain produced 3 million tons of iron New efficient methods of transportation and other innovations created new industries, improved the distribution of goods, increased consumerism and enhanced the quality of life (steamships, railroads, streetcars) New industries – chemical industry, electricity, automobiles) A combination of factors including geography, lack of resources, the dominance of traditional landed elites, the persistence of serfdom in some areas, and inadequate government sponsorship accounted for eastern and southern Europe’s lag in industrial development. The development of the market economy led to new financial practices and institutions (Bank of England, New definition of property rights, insurance) Industrialization in Prussia allowed that state to become the leader of a unified Germany, which subsequently underwent rapid industrialization under government sponsorship. (zollverein, List’s National System) In some of the less industrialized areas of Europe, the dominance of agricultural elites persisted into the 20th century Because of the persistence of primitive agricultural practices and land owning patterns, some areas of Europe lagged in industrialization while facing famine, debt and land shortages (Irish potato famine, Russian serfdom 23. Why was the railroad developed? How did it transform society? Rails reduced friction and allowed a horse or a human being to pull a much heavier load; thus, once a rail capable of supporting a heavy locomotive was developed in 1816, all sorts of experiments with steam engines on rails went forward George Stephenson acquired glory for his locomotive named Rocket, which sped down the track of the just completed Liverpool and Manchester Railway at a maximum speed of 24 miles per hour in 1829 The line from Liverpool to Manchester was a financial as well as a technical success, and many private companies quickly emerged to build more rail lines The railroad dramatically reduced the cost and uncertainty of shipping freight over land o Previously, markets had tended to be small and local; as the barrier of high transportation costs was lowered, markets became larger and ever nationwide o Larger markets encouraged larger factories with more sophisticated machinery in a growing number of industries; such factories could make goods more cheaply and gradually subjected most cottage workers and many urban artisans to severe competitive pressures o In all countries, the construction of railroads created a strong demand for unskilled labor and contributed to the growth of a class of urban workers 24. What was the Crystal Palace? Crystal Palace: the location of the Great Exhibition in 1851 in London; an architectural masterpiece made entirely of glass and iron The more than 6 million visitors from all over Europe marveled at the gigantic new exhibition hall set in the middle of a large, centrally located park; sponsored by the British royal family, the exhibition celebrated the new era of industrial technology and the kingdom’s role as world economic leader Britain’s claim to be the “workshop of the world” was no idle boast, for it produced two-thirds of the world’s coal and more than half of all iron and cotton cloth o More generally, in 1860 Britain produced a remarkable 20 percent of the entire world’s output of industrial goods, the gross national product rose roughly fourfold at constant prices between 1780 and 1851 o At the same time, the population of Britain boomed, growing from about 9 million in 1780 to almost 21 million in 1851; growing numbers consumed much of the increase in total production 25. What was Malthus’ idea about population? Sustaining the dramatic increase in population, in turn, was only possible through advances in production in agriculture and industry; based on the lessons of history, many contemporaries feared that the rapid growth in population would inevitably lead to disaster In Thomas Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population concluded that the only hope of warding off such “positive checks” to population growth as famine and disease was “prudential restraint” Young men and women to limit the growth of population by marrying late in life, but Malthus was not optimistic about this possibility; the powerful attraction of the sexes, he feared, would cause most people to marry early and have many children 26. What was Ricardo’s iron law of wages? Economist David Ricardo spelled out the pessimistic implications of Malthus’s thought; Ricardo’s depressing iron law of wages posited that over an extended period of time, because of the pressure of population growth, wages would always sink to subsistence level Wages would be just high enough to keep workers from starving Even the 1840s, contemporary observers might reasonably have concluded that the economy and the total population were racing neck and neck, with the outcome very much in doubt Perhaps workers, farmers, and ordinary people did not get their rightful share of the new wealth; perhaps only the rich got richer, while the poor got poorer or made no progress 27. How did industrialization spread outside of England? Outside of western Europe industrialization proceeded more gradually, with uneven jerks and national and regional variations Scholars are still struggling to explain these variations as well as the dramatic gap that emerged for the first time in history between Western and non-Western levels of economic production Different rates of wealth and power-creating industrial development, which heightened disparities within Europe, also greatly magnified existing inequalities between Europe and the rest of the world 28. Describe industrialization in Continental Europe In the newly mechanized industrial, British goods were being produced very economically, and these goods had come to dominate world markets; British technology had become so advanced and complicated that few engineers or skilled technicians outside England understood it Continental businesspeople had difficulty finding the large sums of money the new methods demanded, and laborers bitterly resisted the move to working in factories; all these factors slowed the spread of machine-powered industry Nevertheless, western Europe nations possessed a number of advantages that helped them respond to their challenges; most had a rich tradition of putting-out enterprise, which endowed them with experienced merchant capitalists and skilled urban artisans Moreover, while British inventors and entrepreneurs had to discover and implement new technologies on their own, other nations could simply “borrow” the new methods developed in Great Britain European countries had a third asset that many non-Western areas lacked in the 19th century: they had strong, independent governments that did not fall under foreign political control These governments would use the power of the state to promote industry and catch up with Britain