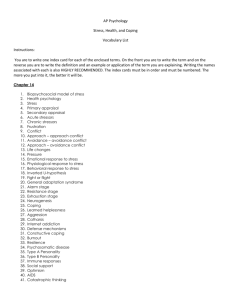

■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 1 2 4 9 11 15 18 21 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Cost Savings vs. Cost Avoidance Definitions and Clarifications Key Issues/ Problems ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Executive Summary Hot Topics in Today’s Supply Chain Management DEFINING COST REDUCTION AND COST AVOIDANCE BRYAN ASHENBAUM CAPS: CENTER FOR STRATEGIC SUPPLY RESEARCH EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Purchasing and supply management departments are under increasing pressure to reduce costs and deliver savings to their organizations’ Case Study I: PSEG bottom lines. Crucial to this mission is the proper categorization of the various types of cost reduction and their application to the company’s operating budgets and profit and Case Study II: NCR Corporation loss measures. Generally speaking, cost reductions come in two different categories: “hard” cost savings and soft“ cost avoidance. However, neither of these has a universally accepted definition or method by which it is tracked and applied to company Case Study III: Northrop Grumman financials. Appendix A: PSEG Cost Reduction Breakdowns and Examples this issue, participants attempted to provide clarity and standardized working At a recent CAPS: Center for Strategic Supply Research Critical Issues conference on definitions for these cost reduction categories. These definitions and clarifications are detailed in the first section of this report. The next section details the following key issues and problems faced by companies as they seek to properly assess cost Appendix B: NCR Cost Reduction and Cost Avoidance Examples contributes advantage ■ MARCH 2006 MISSION STATEMENT CAPS ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■❖ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■❖ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ to competitive organizations by delivering leading-edge research reduction: • “Cancellation” of net savings due to an overall increase in the business unit’s cost structure • Supply management’s role in the cost savings allocation decision • Chronology of supply management’s involvement and the need for budget cuts • Visibility, in terms of systems, people, and metrics • Total cost of ownership (TCO) concept for purchased items/services globally to support continuous • Multi-year issues in cost savings change and breakthrough perform- • Creating a proper incentive structure for supply management personnel ance improvement in strategic sourcing and supply. The report then focuses upon three case studies, detailing selected approaches and best practices in defining, tracking, and validating cost savings and cost avoidance. Finally, Appendices A and B provide additional examples of cost savings and cost avoidance categories at two of the case study firms. Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 2 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ COST SAVINGS VS. COST AVOIDANCE: DEFINITIONS AND CLARIFICATIONS Purchasing and supply management departments are under increasing pressure to reduce costs and deliver savings to their organizations’ bottom lines. To that end, strategic sourcing strategies are developed and sophisticated negotiation techniques are deployed to reduce the prices paid for goods and services.1 In addition, strategic sourcing personnel are encouraged to find new and innovative ways to work with suppliers to reduce mutual costs rather than to simply demand from those suppliers a yearly price decrease. Crucial to this mission is the proper categorization of the various types of cost reduction and their application to the company’s operating budgets and profit and loss measures. Generally speaking, cost reductions come in two different categories: “hard” cost savings and “soft” cost avoidance. However, neither of these has a universally accepted definition or method by which it is tracked and applied to company financials. A great deal of a supply management’s effort results in cost avoidance, yet this category is more intangible than cost savings. As a result, many supply professionals are concerned that they do not receive proper credit for delivering cost avoidance savings to the company. By some estimates, $1 of cost savings can equal $7 (or more) of increased revenue in bottom-line impact, making clear definitions and a way to properly quantify all cost reductions a worthy goal indeed. A brief example might serve to show why clear definitions are necessary. At one company, a purchasing manager negotiates a 5 percent decrease in price for a raw material, resulting in a savings of $100,000 that year. At another company her counterpart successfully resists a supplier’s attempt to raise prices by 10 percent, allowing the company to avoid spending an additional $200,000 that year. Although greater in value, the second savings is also more intangible—is the $200,000 a “real” savings? If so, can a high-level manager put his or her hands on that “saved” $200,000 and re-invest it in the business? This is the very heart of the cost savings versus cost avoidance issue. Cost Savings The CAPS conference participants largely agreed that cost savings (hard) are defined as/characterized by: • Year-on-year saving over the constant volume of purchased product/service. • Actions that can be traced directly to the P&L. • A direct reduction of expense or a change in process/technology/policy that directly reduces expenses. Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 3 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ • Process improvements that result in real and measurable cost or asset reductions. • The examination of existing products or services, contractual agreements, or processes to determine potential change(s) that reduce cost. • Net reductions in prices paid for items procured when compared to prices in A significant challenge place for the prior 12 months, or a change to lower cost alternatives, i.e., [old price - new price] x volume. for supply management professionals is how to properly quantify cost avoidance intangible savings as “real” savings. Generally speaking, cost savings are understood as tangible bottom line reductions resulting in saved money that could be removed from budgets or re-invested back into the business. There also needs to be a prior baseline or standard cost for the purchased product or service so that these savings could be measured against the prior time period’s spend. Cost Avoidance Cost avoidance is a more difficult category to define. Is it simply “everything else” beyond hard price reductions for products and services that are repeat buys? Some definitions of cost avoidance that emerged from the conference include the following. • Avoidance is a cost reduction that does not lower the cost of products/services when compared against historical results, but rather minimizes or avoids entirely the negative impact to the bottom line that a price increase would have caused. • When there is an increase in output/capacity without increasing resource expenditure, in general, the cost avoidance saves are the amount that would have been spent to handle the increased volume/output. • Avoidances include process improvements that do not immediately reduce cost or assets but provide benefits through improved process efficiency, employee productivity, improved customer satisfaction, improved competitiveness, etc. Over time, cost avoidance often becomes cost savings. Needless to say, cost avoidance is more open-ended and is more difficult to quantify. As a result, cost avoidance is something that many people feel free to ignore, or to discount as a “phantom” or lesser savings to the company. Generally, cost avoidance does not hit the P&L directly and does not result in a tangible budget savings that can be pulled out or re-invested. A significant challenge for supply management professionals is how to properly quantify cost avoidance intangible savings as “real” savings.2 Some examples of cost avoidance include: • Resisting or delaying a supplier’s price increase • A purchase price that is lower than the original quoted price Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 4 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ • Value of additional services at no cost, e.g., free training • Long-term contracts with price-protection provisions, i.e., multi-year contracts • Introduction of a new product or part number requiring a new raw material purchase. Spend is lower than previously, but the savings is classified as avoidance because there is no historical comparison. There are some actions related to cost or price that are neither cost savings nor avoidance. (Note the conflict with the list above, as various companies had different ways to recognize cost avoidance.) These include: • Technology development funding used to pay for intercompany goods and services. • Supplier quote used as baseline. • Negotiating an expense increase when industry average is increasing at a higher rate than negotiated. • Negotiating risk mitigation for contract or legal exposures. • First-time spend on a good or service where there is not a defined business unit budget. This section has attempted to provide some working definitions for cost savings and cost avoidance, and to provide some understanding of how firms perceive them and apply them to their budgets and purchasing goals. The next section sketches the key issues and problems that arise as companies try to define and track cost savings and avoidance. KEY ISSUES/PROBLEMS The following key issues and problems have been faced by companies as they seek to properly assess cost reduction: • “Cancellation” of net savings due to an overall increase in the business unit’s cost structure • Supply management’s role in the cost savings allocation decision • Chronology of supply management’s involvement and the need for budget cuts • Visibility, in terms of systems, people, and metrics • Total cost of ownership (TCO) concept for purchased items/services • Multi-year issues in cost savings • Creating a proper incentive structure for supply management personnel “Cancellation” of Net Savings Due to an Overall Increase in the Business Unit’s Cost Structure Cost savings efforts do not occur in a vacuum. The business may be growing, other input costs may be changing, or the strategic mission of the firm itself may be shifting. What often happens is that supply managers may announce a savings of X dollars or of a certain percent, but functional managers who run the various divisions may observe Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 5 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ that their overall cost structure has increased due to other factors. This increase in other areas can obliterate or mask the savings that were realized. How does this affect the recognition of those savings? Does this turn those hard savings into cost avoidance? Many firms indicate that hard savings are only recognized as dollars that could be taken Many firms indicate that hard savings are only recognized as dollars that could be taken out of the budget or reinvested into the business. out of the budget or re-invested into the business. If the overall divisional cost growth flows opposite from supply’s saving efforts in one area, then the savings are not present in a tangible sense. Consider the following sub-scenario of this larger issue. Suppose a company buys 10 widgets for $2 a piece in 2005. In 2006, supply management negotiates a price of $1.50, but volume growth means that 12 of the widgets must be purchased. What savings were truly realized (see the chart below)? The difference in actual spend is only $2. Yet a plausible savings of $5 or $6 could be claimed if either one of the years was held as a baseline volume. How are these savings divided into hard/soft categories? Another view is that there are two savings streams. The first is a “price” variance on the base (2005) volume ($0.50 x 10 units). The second is a “volume” variance base on the additional units purchased in the following year ($0.50 x 2 units). Is the price variance hard savings, and the volume variance cost avoidance? Spend 2005 2006 for Price: Price: Widgets $2.00 $1.50 $20.00 $15.00 $24.00 $18.00 2005 Volume: 10 Widgets 2006 Volume: 12 Widgets Supply Management’s Role in the Cost Savings Allocation Decision A rigorous measurement and tracking process is essential to maximize value from cost reduction initiatives. Supply management is by and large responsible for generating many cost reductions and also for managing this process. The numbers that emerge from this process must be meaningful and recognized by upper management. Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 6 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ That being said, supply management must play a vital yet cautious role once cost savings have been realized and reported. First, supply management and finance must be coordinated on the reporting of savings numbers so that budgets can be assessed properly and so that supply management does not come off as the villain, or get caught up in internecine battles. Second, most conference participants indicated that while supply management identifies the savings, it is the senior executives with P&L responsibility who make the decision regarding the allocation of the savings—whether they are to be removed from the budget and taken straight to the bottom line or reinvested elsewhere in the business. It is supply management’s job to ensure faith in the numbers—to ensure that whether regarded as hard savings or cost avoidance, the benefits were realized overall. The managers can then make decisions regarding the elimination or redeployment of hard dollar savings at their disposal. Chronology of Supply Management’s Involvement and the Need for Budget Cuts A consistent theme in discussion of cost savings focuses on the timing of cost reduction efforts. Often, cost savings efforts are seen as a threat to budgets. No one seems eager to participate in a project that will result in their budget being reduced for the following reporting period. In this case, supply management comes looking for cooperation on cost reduction initiatives and finds a lack of enthusiasm, or perhaps even downright hostility. On the other hand, if the business unit is tasked to reduce its budget first, then supply management can be looked to enable that goal with suggestions for cost savings. When the budget push is on, supply management arrives with a cost-cutting toolkit and receives a much warmer welcome. As such, it almost appears better for supply management to wait to be approached by the functional units after budget cuts are announced, looking like a hero rather than a villain. Of course, this is a rather short-sighted and dysfunctional view of supply management’s role and of the need for continuous improvement. Supply management will be tasked with cost reduction regardless of whether senior managers have been tasked to reduce their budgets by a set amount or not. This is certainly not an endorsement for supply managers to wait until approached by panicked managers in order to gain access. This report is merely pointing out a bureaucratic political reality that supply managers will have to navigate even more carefully than their negotiations with key suppliers. Supply managers need to be aware that the warmth of their reception in other departments may well depend upon the Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 7 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ current climate and attitude toward cost savings and budget-setting at their firm at the given time. Visibility, in terms of systems, people, and metrics For optimal cost reduction efforts, visibility is needed on three levels: systems, people, and measurement. Systems, understood as both IT infrastructure and company For optimal cost reduction efforts, visibility is needed on three levels: systems, people, and measurement. policies, need to be in place so that managers can get a realistic handle on what costs actually are, what areas might benefit from cost reduction efforts, and how company policies are designed to track and execute these savings efforts. Flexible and comprehensive IT systems are crucial, as they are the medium that will provide the visibility needed to accurately assess costs and expenditures. Likewise, processes for executing and tracking cost reduction projects should be in place and available to all personnel. Hierarchical roll-up mechanisms need to be in place to collect, report, and roll up operating unit benefits. Once systems are in place, then adequate staffing must be provided to track savings projects and to consistently fine-tune the procedures and policies. In some companies, a single supply manager individual tracks projects and results in a database. Other firms place responsibility with the individual buyers for entering their own cost savings. Within this second group, there will often be some sort of central auditor or team to examine and extract this data. Finance is also required to verify the cost savings numbers put forth by supply management. It is typical that finance personnel will serve in parallel with those in procurement to track savings and spend. These people are often part of finance with a dotted line responsibility, or can be analysts specifically assigned to the purchasing group. Measurement standardization is the third piece of visibility. Complications arise in calculating cost savings — changes in volumes, different business unit accounting practices, not all units on the same ERP system, etc. Measurement standardization and the use of a set of common metrics are needed to keep the company speaking one “common language” on cost reduction. It is an old but accurate saying that “what gets measured gets improved,” and another that “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” Metrics to track cost savings and cost avoidance should be standardized throughout the company, should be clearly defined, and should be available to all personnel. The establishment of clear metrics and definitions helps avoid the accusations of “fuzzy math” or the arguments over what amount has been saved by a particular initiative. Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 8 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) Concept for Purchased Items/Services It is widely acknowledged that price reductions are only one way to achieve cost reductions.3 The value that global supply management provides goes well beyond mere price reductions; it extends to supplier reliability, purchased goods quality, and initiating early supplier involvement in product design to grow market share. But price reductions are often the only visible and tangible proof of supply management’s effectiveness. How can quality and efficiency issues be factored into savings calculations so that price and differential are not the only proxies for cost and savings? How can production efficiencies, customer satisfaction, and market-share increases be tied back to a single purchased item? In other words, how can a TCO model be developed for an individual purchased item? In some respects, we are chasing the “holy grail” of purchasing with this issue. But the reality remains that consistent year-over-year price reductions are not always feasible. A more expensive good or service that yields a higher market share or greater production efficiency undoubtedly delivers a cost savings to the company, but methods are not in place to effectively tease out this result from other factors. Multi-Year Issues in Cost Savings Many cost savings efforts are multi-year, with realized savings spread out over several reporting periods. Do the cost savings (or at least their recognition) only last for a single year, even though the benefits may flow over a several-year period? For items that have a market scenario, a fixed price over a multi-year period can count as a loss or gain as the commodity market price fluctuates up or down. Many companies counts hard savings on multi-year contracts for the first 12 months, but then the savings in subsequent years are counted as softer cost avoidance (if at all). Others do count savings over the length of the contract, not simply the first time period. However, in the second year, that revised price is built into the budgets of the functional units (see Case Study II: NCR in this report for more examples of multi-year cost reduction approaches, particularly with regard to the calculation of cost reductions, purchase price variance, and carryover). A final thought is that for multi-year contracts, Year One investments are often greater than anticipated savings that year (even though over the lifetime of the contract the savings will be positive). In this case, is supply management denied credit if the subsequent-year savings are not counted to offset the initial year investment? In some instances, the answer seems to be yes, even though many other companies seem Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 9 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ willing to amortize the cost savings over the life of the contract so that the positive impact is recognized. Creating a Proper Incentive Structure for Supply Management Personnel The issues raised thus far all lead to the following question: How should the proper incentive structure be created for supply management personnel? Like anyone else, a If supply management is compensated only for hard savings, then the supply manager will engage in behaviors rewarded by the company. This creates a problem for the company if cost avoidance, multi-year savings, or other cost reduction efforts beyond hard savings do not count toward the supply manager's performance and promotion goals. tendency will be to ignore other forms of cost reduction. If supply management is compensated only for hard savings, then the tendency will be to ignore other forms of cost reduction. The company must clearly lay out what forms of cost reduction count toward goals, even if there is a scale of importance attached to them. There are many improvement projects (such as risk mitigation) where the cost of implementation requires hard dollars (training, hardware/software, capital equipment, reconfiguring facilities, etc.) but the short-term benefits are “soft.” Supply management must be able to receive some credit for these. Likewise, it must be determined clearly who gets the credit for the benefits delivered from cross-functional team initiatives to improve processes and reduce costs. If, for example, supply management works with logistics to reduce carrier freight, which function gets the credit? Do both parties get full credit, or half-credit each? (Of course, the money is only counted once, but some companies still give both parties equal credit for full benefit delivered in terms of individual promotion plans). One idea that has been suggested but has yet to see much traction is to provide supply managers with variable compensation as part of their incentive for meeting savings goals. Such bonus plans are of course common for senior management, marketing/sales, and production. Perhaps such bonuses would also have a positive effect on the company’s overall cost reduction goals. CASE STUDY I: PSEG Background Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG) is a publicly traded energy company headquartered in New Jersey. Main subsidiaries include PSEG Power LLC, Public Service Electric and Gas Company (PSE&G) and PSEG Energy Holdings LLC. It has approximately 10,500 employees and annual revenues of $11 billion. (www.pseg.com). PSEG is currently undergoing a merger with the Exelon Corporation (www.exeloncorp. Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 10 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ com). The merged company is expected to employ over 28,000 people, have approximately $27 billion in annual revenue, and serve over 9 million customers. Supply chain management (SCM) at PSEG is a hybrid organization; procurement is a center-led group, while logistics and operations are fairly decentralized. The centralized procurement group seeks to leverage cross-company spend volume (wires, transformers, street services, etc.) and indirect (that which supports the plants in operation) purchases. Tactical plant-level purchases are executed though a central procurement operations group. PSEG’s spend is approximately $1 billion in non-fuel materials and services (another group purchases and trades fuel). Approaches to Hard Savings vs. Cost Avoidance SCM as an organization has evolved from a decentralized organization to a centralized organization within the shared services organization. The mission was to generate $25 million in savings. The objective was to create a rigorous savings measurement and tracking process to maximize value from SCM initiatives and to ensure that the value from these initiatives was realized. PSEG categorizes cost savings into A, B, and C categories based upon bottom line impact and the hard savings/avoidance demarcation: A = Price or cost increase/decrease on recurring spend B = Value-added savings/increase where no prior price/cost information exists C = Avoided costs More comprehensively, the categories break down as follows (see Appendix A for specific examples and calculations for these savings categories). ❖ Category A • A-1. Calendar-year negotiated savings from prior agreement • A-2. Continuous improvement • A-3. PO extensions with price increases ❖ Category B • B-1. Calendar-year negotiated savings where no prior agreement exists • B-2. Process savings (budget-impacting) ❖ Category C • C-1. Process savings (non-budget-impacting) • C-2. Cost avoidances (non-budget-impacting) Some Category B savings are not hard and do not count toward actual budgetary impact. Category C savings are clearly cost avoidance and are therefore the hardest to quantify or make a convincing case for budget impact. Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 11 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ The PSEG tracking and validation process for cost savings projects is shown below in Figure 1. The upper half of Figure 1 shows the tracking and reporting process to document the savings from various savings projects. Projects with a savings (or increase) greater than $25,000 go through extra approval steps, ultimately being signed off by the internal Quarterly validation meetings are held to functional manager and the vice president of SCM. The lower half of Figure 1 shows the validation process by which savings resulting determine the budgetary from cost reduction projects are applied to company financial statements and budgets. impacts and budgets are Quarterly validation meetings are held to determine the budgetary impacts and budgets adjusted accordingly. are adjusted accordingly. Figure 1 ➢ The SCM group pursues savings and presents them to senior managers. These senior managers determine the budget impact (i.e., does the budget get reduced or do the savings get migrated to other areas where the resources are needed). CASE STUDY II: NCR CORPORATION Background NCR is a publicly traded hardware, software, and data warehousing company with 28,000 employees and approximately $6 billion in annual revenue (www.ncr.com). Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 12 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ NCR’s product offering includes ATMs, financial services kiosks, financial software, check imaging technology, retail point of sale (POS) software, data warehousing, and computer printer consumables. NCR was founded in 1884 as a manufacturer of mechanical cash registers and went public in 1926. Strategic purchasing at NCR is center-led, with a CPO and direct reports responsible for international purchasing offices, compliance, indirect spend, shared direct spend and major initiatives. There are supply line management roles in each business unit that Figure 2 Lever Rate Calculation Data Required - Net reductions in prices paid for items procured when compared to prices in place for the prior 12 months or change to lower cost alternatives [Old price - New price] * Volume •Summary PPV reports from the BUs •Copies of the old and new contracts plus data that supports actual volumes (POs, etc.) •Travel information (# of tickets, cost per ticket, etc.) from travel provider •Temporary Services information (# of hours, rates, etc.) from Managed Service Provider Rate “Market” - Industry market movement (positive and negative) by commodity [Old price - New price] * Volume. •Data from manufacturers (e.g., price information form Dell, Solectron, etc.) Demand - Proactive programs to reduce usage [Volume reduction] * Price. •Copies of cancelled contracts (including emails or other written documentation to suppliers) •Lists of names (mobile phone cancellations, etc.) •Temporary Services information (# of directed hires, moving work in house, etc.) from Managed Service Provider Compliance - Calculations vary depending on the commodity and type of cost reduction. Driving demand to approved programs or preferred suppliers and eliminating the premium paid when “outside” of the program. •Lists of names (mobile phones and pagers — getting them on the correct programs) •Temporary Services information (# of people outside the bill rates, etc.) from Managed Service Provider •Travel exception report from travel provider E&S - (Engineering & Proactive programs which change the manufacturing product specifications and designs [Old bill of materials – New bill of materials] * Volume. •Summary MUV reports from the BUs Specification) Monthly/Quarterly Commodity Director submit cost reductions Cost reductions reviewed & validated by Spend Analyst Quarterly Sourcing Council Review held Quarterly BU CFOs reviews held and results locked off Reports published to Procurement community Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 13 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ report to the CPO as well as to their own business units. Transactional purchasing (PO release, receipts, and day-to-day operational activities) is decentralized. Approaches to Hard Savings vs. Cost Avoidance Cost reduction efforts at NCR involve the examination of existing products or services, contractual agreements, or processes to determine potential changes that reduce cost. NCR defines cost avoidance as those savings that do not NCR looks at five different cost reduction levers: rate, rate market, demand, compliance, and engineering and specification (E&S). Figure 2 explores these cost levers in greater detail and provides the formulae for their calculation (and data required to do so). impact the P&L and do not lower cost compared to historical results. Figure 2 also provides an overview of the tracking and validation process used by NCR. Monthly cost reductions are validated by a designated spend analyst, and a quarterly sourcing council (the CPO, his/her direct reports, and business unit supply line management leads) reviews the aggregate savings numbers, which are then reviewed by the CFOs and applied to the financial systems. Examples of cost reduction at NCR are shown in Appendix B. NCR defines cost avoidance as those savings that do not impact the P&L and do not lower cost compared to historical results, but that instead minimize or cancel negative bottom line impacts from potential price/cost increases. NCR’s methods of calculating/measuring cost avoidance are shown below: ❖ Price increase avoidance • Calculation: [Proposed price increase – negotiated price] x volume ❖ Cost avoidance for one-time purchases • Calculation: [Quoted price – Negotiated Price] x Volume. Use the final contract price and the first offer of the preferred supplier. If no preferred supplier then use the average of all offers or the first offer of the selected supplier; if averaging the offer would skew the savings, use judgment. ❖ Value added savings — Goods or services that are received and have an intrinsic value not billed as part of the contract. • Calculation: Value of additional service (which is at no cost) Examples of cost avoidance at NCR are shown in Appendix B. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate NCR’s approach to evaluating cost reduction changes on standard costs, cost reduction, purchase price variance (PPV), and carryover. NCR also tracks spend in low-cost regions, spend through global suppliers, and spend through reverse auctions. Reverse auctions in particular are perceived to give a greater Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 14 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Figure 3 Figure 4 NCR Standard Cost for Current & New Products Cost Reductions ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Current Products New Products Carryover Not in PPV N/A New PPV ICR - Not in Cost Reduction Considered Cost Avoidan ce Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 15 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ transparency to market prices. These auctions are conducted with a standardized set of terms & conditions (i.e., payment terms) and no post-auction bids are accepted. The lowest bidder is not necessarily guaranteed to win (some auctions consider supplier switching costs). In more commoditized markets (e.g., memory), the lowest bidder is guaranteed to win the bid. Cost reduction at Northrop Grumman focuses upon process improvement initiatives and on defining and Up until this year, hard savings have been the only measure that “counted” for purchasing employees from a performance and promotion standpoint. However, in 2006 NCR will be implementing cost avoidance measures as well. From NCR’s perspective, cost avoidance often provides greater benefit to the company, because the higher cost is never incurred in the P&L statement. CASE STUDY III: NORTHROP GRUMMAN tracking key metrics to track performance. Background Northrop Grumman is a global defense company employing 125,000 people and with annual revenues of approximately $30 billion (www.northropgrumman.com). It is a leading defense systems integrator, the largest military shipbuilder and the largest provider of airborne radar and electronic warfare systems. The integrated systems division employs 14,000 people and had 2004 revenues of $4.7 billion. The Materiel Organization at Northrop Grumman Integrated Systems reports to the vice president of operations. Materiel is organized into integrated delivery teams (which focus on business area and programmatic unique issues) and shared services teams, which are centralized functions for supplier quality/supplier performance, general procurement, major subcontracts, business management, materiel fulfillment, and strategy. Approaches to Hard Savings vs. Cost Avoidance Cost reduction at Northrop Grumman focuses upon process improvement initiatives and on defining and tracking key metrics to track performance. Process improvement initiatives contain the following key elements: • Strong executive support • Process owner commitment and stakeholder engagement • Program office infrastructure — people, processes, and systems • Communication plan • Project sponsorship and resource prioritization • Funding The following types of metrics are tracked and defined to measure the success of process improvement initiatives: Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 16 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ • Cost savings (hard benefits) • Cost avoidance (soft benefits) • Cash flow • Sales/revenue • Customer benefits • Non-financial Definitions of cost savings and cost avoidance at Northrop Grumman have been included in the previous section of this report that detailed definitions and clarifications. Some examples of the metrics tracked in these areas include: • Cycle time reductions resulting in lower unit cost (hard savings) • Reduced process operating expenses (hard savings) ■ Equipment/material ■ Manpower ■ Scrap/rework ■ Hardware and software licensing and maintenance costs • Productivity improvements that don’t result in staffing reductions (soft savings) • Process improvements that increase asset utilization, thus avoiding future capital or lease investment (soft savings) • Reductions in liability and risk premiums (soft savings) Northrop Grumman’s definition of cash flow savings is: process improvements that result in real, measurable, and permanent improvements in the balance sheet (such as short-term assets, receivables, payables, etc.). Examples include: ■ Negotiating better accounts receivable/payable terms ■ Improving internal invoicing processes resulting in a lower receivables balance ■ Eliminating/postponing planned capital investments Northrop Grumman’s definition of sales improvement is: process improvements that result in revenue increases, additional funding, contract change, etc. Examples include: ■ Process improvements related to technology insertion motivating customers to place additional orders ■ Process improvements reduce per unit cost resulting in sales to new customers Northrop Grumman’s definition of customer benefits is: process improvements that result in customer benefits not covered by current contractual efforts. Examples include: ■ Process improvement project improves unit quality and performance, eliminating need for customer quality personnel Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 17 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Improved unit design reduces scrap/rework at customer facility after unit delivery Northrop Grumman’s definition of non-financial metrics is: those metrics that focus on the cost, quality, and cycle time of a process and its outputs. The objective in this case is the drive toward process maturity. Mature processes are statistically stable, standardized, lower in variation, and generally achieve desired results. Northrop Grumman generally gives equal credit to various functions that participate on cross-functional teams that yield significant cost savings. The money can only be counted once, but from a score-keeping (i.e., counting toward performance and promotion plans) standpoint, multiple functions can receive full credit for the savings. Endnotes Smock, Doug (2002) “Buyers Shift Strategies as Cost Reduction Goals Grow,” 1 Purchasing, Vol. 131, No. 14, pp. 13-14. Keen, Jack M. (1997) “Turn ‘Soft’ benefits into Hard Savings,” Datamation, Vol. 43, 2 No. 9, p. 38. Porter, Anne Millen (1994) “Beyond Cost Avoidance,” Purchasing, Vol. 117, No. 8, pp. 3 11-12. Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 18 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ APPENDIX A: PSEG COST REDUCTION CATEGORY BREAKDOWNS AND EXAMPLES Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 19 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 20 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Critical Issues ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ REPORT ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ 21 ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ APPENDIX B: NCR COST REDUCTION AND COST AVOIDANCE EXAMPLES Cost Reductions - Examples Lever Example Rate Year over year net reduction in prices paid Demand Proactive programs to reduce usage Compliance Driving demand to approved programs Engineering & Specification Programs to change product design & specifications Cost Reduction •You have a contract in place for catering services. If you renew your contract for the exact same service at a lower cost, this would be classified as rate cost reductions. ✓Old Contract - $100K •Your company has decided only certain employees will have cell phones, as a result, 100 cell phones are eliminated from the total cell phone population. ✓Cell Phones Eliminated – 100 •Your company has three preferred cell phone providers. A program is launched to ensure all employees are using the preferred suppliers. 1,000 employees are discovered to be paying a $10 premium. These employees were moved to one of the three preferred suppliers. •Your company redesigns Widget ABC to use plastic components instead of metal ones. The new bill of materials shows a net reduction in cost of $10/unit. 10K units were manufactured in the current year. ✓New Contract - $80K ✓Cost Reduction – $20K ✓Monthly Cost - $40/phone ✓Cost Reduction – $4K/Month or $48K/Yr ✓Cost Reduction – $10K/Yr ✓Cost Reduction – $100K/Yr Cost Reductions - Examples Cost Avoidance Type Price Increaes Avoidance Cost Avoidance for One Time Purchases Value Added Savings Example Cost Reduction •Your supplier tells you they are having a 15% rate increase. However, by negotiating, you are able to hold the increase to 10%. The 5% difference would be classified as cost avoidance. Had you not taken action your company would have paid more. •Your company needs to purchase Widget AB for a one time project, you have never purchased this product before. You receive quotes from your preferred supplier as well as two other suppliers. You choose to purchase from Supplier B. •Your company contracts with a local temporary agency to hire contractors for a short term project. To ensure the project is completed on time the agency also sends a on-site manager to the job site. The value of the on-site manager is $200/day. You did not contract for the on-site manager nor are you billed for the services. ✓Old Contract price - $100K ✓New Contract price - $110K ✓Cost Reduction - $0 ✓Cost Avoidance - $5K ✓Preferred Supplier Quote - $40 ✓Supplier B Quote - $25 ✓Supplier C Quote - $35 ✓Cost Avoidance = $15 ($40-$25) ✓Cost Avoidance - $200 * Number days Critical Issues Report, March 2006; www.capsresearch.org