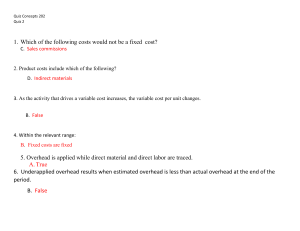

Bridgeton Industries: Automotive Component and Fabrication Plant (ACF): Case Analysis Case Overview In the 1980s, the Automotive Component and Fabrication Plant (ACF) of Bridgeton Industries loss market share due to foreign competitive pressure and oil price shock, leading to a number of plant closings. To determine where to cut costs, Bridgeton hired a consulting firm to analyze the cost competitiveness of its product lines, which led to its decision to cease production of mufflers and oil pans at the end of model year 1988 and resulted in the loss of jobs. Despite improved production efficiency, the manifold line was downgrade and identified as a candidate for outsourcing in 1990. Management’s impulse to proceed with caution in its decision to outsource manifolds, which if produced internally, could lead to higher sales and profit in the long-run given the prospect that future increases in emission standards could boost demand and price for manifolds. To assist ACF’s management in deciding on a suitable production strategy in a market facing increased competitive pressure, we evaluated: (1) trends in overhead allocation rates; (2) the appropriateness of ACF’s cost system for making strategic non-routine decisions (i.e., outsourcing); and (3) 1991 budget projections for alternative decisions: to outsource or not to outsource manifolds. Question # 3: Expected gross margins for given products 1 and 2 based on 1988 and 1990 budgets Expected gross margins for two hypothetical products are estimated as a percentage of selling price for each product based on ACF’s 1988 and 1990 model year budgets, assuming selling price, material and labor costs are constant. We first determined the total overhead (burden) for each of the years as a percentage of direct labor (Exhibit 1). In 1988, the overhead rate was 434.5% ($109,890 ÷$25,294) and in 1989, the overhead rate was 563% ($79,393 ÷$14,102). We calculate overhead for each product by multiplying the overhead rate by labor cost. As seen in Exhibit 2, we added the material and labor costs to the total overhead, which provides the total costs for each product in each year. We then obtain gross margin for each product in each year by calculating selling price less total costs and then estimate gross margin as a percentage of the selling price. From Exhibit 2, we see that gross margin percentages declined from 1988 to 1990 by 55.36% and 35.16% for products 1 and 2 respectively, resulting from a significantly higher overhead allocation rate in 1990 (563%) than in 1988 (434.5%). This suggests that outsourcing muffler/exhausts and oil pans at the end of 1988, did not improve ACF’s profitability. While ACF was able to reduce overhead costs by about 30%, outsourcing adversely impacted the gross margins of ACF’s two remaining product lines which were overburdened by transferred fixed costs associated with the production of muffler and oil pans (reflected in the nearly one-third increase in the overhead rate from 434.5% in 1988 to 577.4% in 1989). This increase in the overhead burden can be attributed to the significant decrease in direct labor that 0 resulted from the outsource decision; in 1989, there was a 46.48% drop in direct labor costs (60 direct labor jobs were lost). Notably, while budgeted sales fell by almost 40%, ACF’s overhead costs only fell by about 30%. In sum, overhead allocation rates had a large impact on profitability even with a drastic decline in overhead. Question #4: Appropriateness of product costs reported by the cost system for strategic analysis The product costs reported by ACF’s cost system are not entirely appropriate for strategic non-routine decisions such as outsourcing. For its overhead costs, ACF relies on a single cost driver—the cost of direct labor—to allocate overhead to its product. A close examination of ACF’s overhead allocation reveals the limitations of traditional cost systems. ACF’s use of one allocation base, direct labor cost, does not allow for effective allocation of overhead costs to each product, given that direct labor does not reflect ACF’s recent productivity improvements and has limited value added as a single cost-driver, given that ACF’s production processes are highly automated. One input cannot drive the costs of all overhead accounts. Given that ACF plant is highly mechanized, using machine hours as a cost-driver would more accurately reflect the distribution of overhead among products than direct labor costs. If AFC continues to misallocate its overhead, management may run the risk of overcosting labor-intensive, high-volume products. This causes strategic analysis of decisions to be flawed as can be intuited from the significant decline of gross margins resulting from ACF’s decision to outsource mufflers and oil pans. Given ACF’s product diversity, tracing overhead to the correct product is important to understanding the profitability of each product. Question #5: Estimated 1991 model year budget given alternative outsource decision The manifold product line became a candidate for outsourcing in 1991. To determine the impact of outsourcing manifold production on ACF, we estimated the plant’s 1991 model budget under two scenarios: (1) the continued production of manifolds and (2) the outsourcing of manifolds. Under Scenario 1 (no changes to product line), which assumes selling prices, volumes, material and direct labor costs remain unchanged, we kept the overhead burden at the 1990 level of 563% of direct labor, which assumes that no new efficiencies in overhead costs are achieved in 1991 (Exhibit 3). Under this scenario, if Bridgeton continues internal production of its manifold line at the ACF plant, total revenue would remain at $226,542; direct materials cost at $69,546; and direct labor costs at $14,102 (Exhibit 3). In 1991, factory profit would be $63,501 with a gross margin of 28% (Exhibit 3). Under Scenario 2, where manifold production is outsourced, we assume selling prices, volumes, and material cost for fuel tanks and doors remain the same. Direct material and labor costs for manifolds would no longer be incurred (see Exhibit 3). Outsourcing the production of the manifold line would result in total revenue of $133,422; direct material costs at $33,821, and direct labor costs at $7,562 (Exhibit 3). 1 The first step in determining factory profit and gross margin under Scenario 2 was to account for overhead costs account changes. Overhead is applied as a percentage of direct labor costs. Exhibits 1 and 3 show that direct labor costs decreased by 46% from 1988 to 1989 from outsourcing muffler systems and oil pans. From Exhibit 3, under scenario 2, we see outsourcing manifolds from 1990 to 1991 would also decrease direct labor costs by 46%. We estimate the changes in overhead accounts from 1988 to 1989 (when direct labor decreased by 46%). We assume that if the change in an overhead account is close to 46% (the change in direct labor costs from outsourcing) then it may be considered a variable account. Where the change is not close to 46%, we assume the overhead account is fixed. Given these budget assumptions, we are able to observe that overhead accounts 2000, 3000, and 12000 are highly variable and decrease by about 46% with outsourcing (Exhibit 3). Under Scenario 2, where overhead is fixed (see analysis above), Bridgeton should use the same 1990 overhead cost. Where overhead is variable, Bridgeton should multiply their 1990 overhead account balances by direct labor ratio (total direct labor costs in 1991/total direct labor costs in 1990) to get the budgeted overhead costs in 1991. If manifolds were outsourced in 1991, the overhead allocation rate based on direct labor costs would be 855.7%; overhead costs would total $64,710; and factory profit would be $27, 329 (Exhibit 3). Using these overhead costs in our analysis, we determined that the total profit would be $27,329 in 1991 if manifolds were outsourced. If the ACF continues production of manifolds, its profit would be $63,501. If the ACF continues producing manifolds, its overhead allocation rate would be 563%, which is the same as the 1990 rate; in contrast, the allocation rate would increase to 855.7% if the facility outsourced its production of manifolds. Recommendations Bridgeton should not outsource manifolds in 1991, as this would make ACF less profitable; factory profit would decrease from $63,501 to $27,329 (Exhibit 3). Even if manifold production is outsourced, ACF possesses a fixed overhead that will transfer to the other product lines (fuel tanks and doors), making them less profitable. We recommend AFC apply diverse cost-drivers, including machine hours, to few cost pools. This would provide a more accurate estimate of manifold’s profitability and costs and allow for a more accurate identification of product lines contributing the most to variable overhead costs. It would also allow for the development of more competitive pricing among products. Lastly, when applying overhead, the cost of unused capacity should be considered. 2 Appendix Exhibit 1. Allocation of Overhead at ACF (1987-1990) Year Total sales Total overhead costs 1987 1988 1989 1990 $330,154 $351,071 $216,338 $226,542 $107,954 $109,890 $78,157 $79,393 Total direct labor costs $24,682 $25,294 $13,537 $14,102 Overhead allocation rate (Total overhead costs/Total direct labor costs) 437.4% 434.5% 577.4% 563.0% % Change in overhead allocation % Change in direct labor costs % Change in sales % Change in overhea d costs -0.66% 32.89% -2.49% 2.48% -46.48% 4.17% 6.34% -38.38% 4.72% 1.79% -28.88% 1.58% Exhibit 2. Expected Gross Margins for Products 1 and 2 (Model Year Budgets 1988 and 1990) Product Per unit Expected Selling Price (P) Standard Material Cost (MC) Standard Labor Cost (LC) 1 Product 2 1988 $62 1990 $62 1988 $54 1990 $54 $16 $16 $27 $27 $6 $6 $3 $3 434.5% 563% 434.5% 563% Overhead Costs (OAR*LC) $26.07 $33.78 $13.03 $16.89 Total Costs (MC + LC + OC) $48.07 $55.78 $43.03 $46.89 Gross Margin (P – Total Costs) $13.93 $6.22 $10.97 $7.11 10.03% 20.31% Overhead Allocation Rate (OAR) Gross Margin % (Gross Margin/Price) Change in Gross Margin % 22.47% -55.36% 13.17% -35.16% 3 4