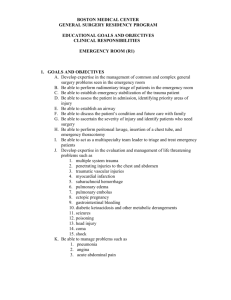

DOI: 10.1308/147363514X14042954770238 Trainees' Forum In an effort to improve standards and safeguard against mishaps, strategies used in commercial or military settings are increasingly being explored. In this article by Wood et al the application of a modified military combat estimate to plan orthopaedic trauma fracture care is described. Although the article highlights its use in orthopaedics, the adoption of strategic planning can be applied to any surgical discipline using the framework described. We welcome proposals for articles in the Trainees’ Forum. Authors wishing to submit an unsolicited study, review or editorial should email a short bullet-point outline of the proposed article (of no more than 250 words) to bulletin@rcseng.ac.uk. David Sanders Series Editor Ann R Coll Surg Engl (Suppl) 2014; 96: 363–365 The seven questions: a novel surgical planning strategy based on military doctrine Ryan J Wood Specialty Registrar in Trauma and Orthopaedics1 Major Jeremy Granville-Chapman Specialty Registrar in Trauma and Orthopaedics2 Colonel John C Clasper Consultant in Trauma and Orthopaedics Surgery2 1 Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust 2 Frimley Park Hospital Foundation NHS Trust Surgical planning is the first step in operative fracture management. The degree of planning that is required is determined by a number of factors, including the nature of the injury mechanism and its concomitant physiological insult, complexity of the fracture and region, expertise of the surgical team and equipment limitations. The Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) foundation believe planning encourages the surgeon to focus on the fracture pattern, fixation technique and surgical approach. This aids identification of problems that may be encountered, which when anticipated may be avoided or more easily overcome. It has benefits on a number of additional levels for the surgeon, trainees, theatre staff and patients alike. AO suggests four sequential stages in surgical planning. The first three are reconstruction, decision making and fixation. These then lead to the fourth stage: the surgical tactic, or a series of steps to be undertaken in the operating theatre.1 Beyond this guidance, formal planning prior to procedures is rarely practised and of varying quality, depending on the experience and character of the operating surgeon as well as the centre at which the patient is treated. It is a topic that is touched upon in the wider literature by experienced orthopaedic surgeons offering their advice and tips.2,3 For many low-volume trauma surgeons, the process of fracture fixation can seem like a battle. A number of factors can conspire to work against the surgeon and it sometimes seems as though the surgical team is overmatched by the problems thrown at it. Adopting a military level of planning and execution may therefore optimise the chances of a successful outcome. With this in mind, this paper explores a novel method of surgical planning that draws inspiration from British military doctrine and the estimate process. It benefits from a more global approach that encompasses logistic as well as surgical constraints. Combat estimate – the ‘seven questions’ The estimate process is used by the British military to allow the formulation of considered plans. It is a logical process by which a commander, faced with a problem, may arrive at a decision as to how that problem can be solved and the steps required to achieve the desired outcome. The estimate occurs at three levels: the operational, tactical and combat estimates, with the latter being ideal for generating tempo at a local level. It can be described as the process by which ‘an adequate and flexible plan is developed in a reasonable amount of time’.4 In real terms, the combat estimate is used by commanders of smaller units on the ground to develop plans in a timely fashion to overcome specific military situations or adversaries. This combat estimate is often referred to as the ‘seven questions’. By going through each of the questions, problems and additional requirements will be identified. These may be in terms of information that is required or a piece of specialist equipment that will be needed. This then generates specific requests for information or equipment that will need to be acted upon. The process offers a very succinct problem-solving paradigm that, when adapted, lends itself to the field of surgical planning, particularly in trauma surgery. In this case the military commander is the surgeon, and the foe is the fracture. The military approach can 363 THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS OF ENGLAND BULLETIN be easily adapted to lend structure to the thought processes involved in planning an operation for orthopaedic trauma. The seven questions of the combat estimate and our proposed surgical corollary are shown in Figure 1. FIGURE 1 SURGICAL ESTIMATE – THE ‘SEVEN QUESTIONS’ Broadly, questions 1 to 3 are concerned with the development of situational awareness and understanding of the mission and the battlespace. These then feed into questions 4 to 7 to allow development of a course of action. In surgical terms, questions 1 to 3 are similarly focused on understanding the fracture and 4 to 7 on designing and documenting a surgical plan. Question 1: what is the fracture pattern/location? This requires identification of the nature of the injury. What pattern/configuration is the fracture? Where in the bone is it located – is it intra- or extra-articular? The fracture will usually have been identified on plain radiographs, but in order to answer question 1 fully, requests for further information (RFIs) such as cross-sectional imaging may be required to delineate the anatomy of the injury. Question 2: what mode of fixation do I want to employ? This question requires the application of the principles of basic fracture management and asks whether primary (direct) or secondary (indirect) bone healing is desirable and how that is best achieved. For intra-articular fractures, anatomical reduction and absolute stability with interfragmentary compression may be required and the surgical strategy and equipment will need to be adapted to achieve this. The same applies for relative stability and question 2 will generate surgical options, but question 3 needs to be considered before choosing the most appropriate of the surgical fixation options. Question 3: what can I do to optimise fracture healing? Having identified the fracture type and the surgical options available, one must also consider fracture healing and how to optimise it. This will depend on the location of the fracture, patient comorbidities and the nature of the surrounding soft-tissue injury. It may generate the need for further information in terms of the patient’s medical, drug 364 FIGURE 2 SURGICAL ESTIMATE FLOWCHART and social histories. Additional needs such as the involvement of other medical and surgical specialties may also become apparent at this stage – eg plastic surgery to aid in management of open fractures or input from medical teams to mitigate the risk of comorbidities. Question 4: where and when will the operation need to take place? Having built up a picture of the patient and the fracture in questions 1 to 3, the urgency of fixation and the ideal timing of surgery should be apparent. This may be on the next available trauma or emergency theatre list but may also involve additional planning if the equipment or personnel requirement so dictate. It may involve a decision to proceed with damage-control surgery and a staged definitive solution. Question 5: what resources do I need to accomplish each action/effect? We now have an understanding of how the fracture is going to be fixed THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS OF ENGLAND BULLETIN and where and when this may happen. This allows consideration of the surgical equipment, supporting personnel (eg anaesthetists, radiographer) and implants that will be required. Specific limitations at this point may feed back and alter the considerations made in the previous question – in some cases changing either the timing of surgery or the mode of fixation to be adopted (in the developing world, image intensification is not always available. Closed reduction techniques and minimally invasive techniques may not therefore be feasible). Question 6: in what order do I need to perform the steps of the operation? This represents the formulation of a step-by-step surgical plan, based on the considerations above. This reflects the AO principles and will inform not only the operating surgeon and his or her assistant(s) but also the rest of the theatre team. The generation of a surgical planning diagram is already taught on AO courses, both basic and advanced. It can be done either on TraumaCad ® systems or on paper and includes: patient positioning and preparation; surgical approach and hazards therein; fracture reduction techniques and contingency measures; implants to be used and their sequence of application; and wound management and closure. This plan can be displayed in theatre for reference for all before and during surgery. Question 7: what postoperative measures do I need to impose? Prior to surgery, thought can be given to the postoperative control measures that can be put into place to ensure that rehabilitation of the patient begins at the earliest possible moment. This would include further antibiotics, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, weight-bearing status of the patient and range of movement of adjacent joints. Some aspects of this may be altered postoperatively to reflect intra-operative findings and events (eg quality of bone for screw purchase). By considering these factors preoperatively, one can undertake a more informed consenting process in terms of likely inpatient stay, rehabilitation constraints and patient expectations of final outcome. Summary All surgeons would attest to the importance of considered planning in trauma surgery. This seven-question surgical estimate, derived from a combat planning tool, provides a concise structure by which many aspects of planning can be considered. It should help surgeons in their approach to complex trauma. For surgeons who regularly tackle complex fractures in a high-volume trauma centre, this may be a formalised version of an analysis that already occurs on a daily basis. Its strengths may well be in improving planning in smaller centres where logistical support for trauma is not so robust. From a training perspective, it has many added advantages. Trainees might be encouraged to undertake and present their surgical estimates to their supervising consultants. This would form the framework for a case-based discussion and lead naturally onto a procedure-based assessment as the trainee executes their plan. Above and beyond the surgical plan, this planning tool develops an awareness and understanding of the logistical constraints to surgery that can alter decision making. In terms of feedback, the structured estimate can be interrogated to see if it ‘survived contact’ with the patient. The old military adage that ‘no plan survives first contact’ probably runs true in surgery but with adequate planning and subsequent critical analysis, the ability to remain flexible and adapt can be increased. Any areas where unexpected problems arose, or contingency measures were required, can be highlighted and inform future planning and personal development. We commend this approach to all surgeons operating on trauma patients. References Porteous MJ. Pre-operative planning. In: Ruedi TP, Buckley RE, Moran CG, eds. AO Principles of Fracture Management. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2007. 2. Graves ML. The value of preoperative planning. J Orthop Trauma 2013; 27: S30–34. 3. Martin CR. Preoperative planning for fracture management. Am J Orthop 2012; 41: E128–129. 4. Estimates. Army Doctrine Publication: Operations: Ministry of Defense; 2010. 1. 365