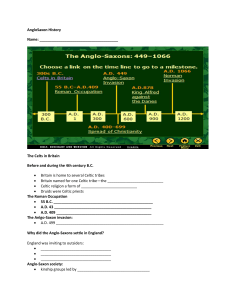

1. Invasions. The pre-Celtic period. What makes the Scottish, Welsh, English and Northern Irish different from each other? About 2,000 years ago the British Isles were inhabited by the Celts who originally came from continental Europe. During 1,000 years there were many invasions. The Romans came from Italy in 43 A.D. and, in calling the country ‘Britannia’, gave Britain its name. The Angles and Saxons came from Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands in the 5th century and England got its name from this invasion (Anglelands). The Vikings (Scandinavians) arrived from Denmark and Norway throughout the 9th century and in 1066 the Normans invaded from France. These invasions drove the Celts into what is now Wales and Scotland, and they remained, of course, in Ireland. The English, on the other hand, are the descendants of all the invaders, but are more Anglo-Saxons than anything else. The various origins explain many of the differences found between England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland – differences in education, religion and the legal systems, but most obviously, in language. As far as historical research could establish, the first inhabitants of the British Isles were nomadic Stone Age hunters. Those newcomers must have been a Mediterranean people. Their burial places in Cornwall, in Ireland, in the coastal regions of Wales and Scotland are found to be either long barrows that is manmade hills or huge mounds covering hutlike structures of stone slabs. These people are thought to be settled on the chalk hills of the Cotswolds, the Sussex and Dorset downs and the Chilterns. They were joined after a few centuries by some similar southern people who settled along the whole of the western coast, so that the modern inhabitants of Western England and Wales and Ireland have good archaeological reasons to claim them for their forefathers (the time is usually given as around 2400 BC. 2. The Celtic invasion. The Romans invasion. Anglo-Saxon invasion. Celtic invasion Around 700 BC, another group of people began to arrive. Many of them were tall, and had fair or red hair and blue eyes. These were the Celts, who probably came from central Europe or further east, from southern Russia, and had moved slowly westwards in earlier centuries. The Celts were technically advanced. They knew how to work with iron, and could make better weapons than the people who used bronze. It is possible that they drove many of the older inhabitants westwards into Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The Celts began to control all the lowland areas of Britain. the ancestors of many of the people in Highland Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and Cornwall today. knowledge of the Celts is slight. At first most of Celtic Britain seems to have developed in a generally similar way. The Celts were organised into different tribes, and tribal chiefs were chosen from each family or tribe, sometimes as the result of fighting matches between individuals, and sometimes by election.The last Celtic arrivals from Europe were the Belgic tribes. to settle in the southeast of Britain. Belgic tribes were different from the older inhabitants. The Celtic tribes continued the same kind of agriculture as the Bronze Age people before them. But their use of iron technology and their introduction of more advanced ploughing methods made it possible for them to farm heavier soils. they continued to use, and build, hill-forts. Celts were highly successful farmers, growing enough food for a much larger population. The Romans invasion The Romans came from Italy in AD 43 and in calling the country “Britannia” gave Britain its name. At the time of the Roman’s first expedition (Caesar’s expedition in 55 BC when a 10-thousand strong Roman army was repulsed by the ironweapon-possessing Celts with the help of the Channel storms) the Belgic tribal chief Cunobelin (Shakespeare’s Cymbeline) united the Celtic tribes of southern Britain under his rule and called himself, after the Roman fashion, “Rex Britonum” that is “King of the Britons” – a title which was impressed on the coins that he struck in his capital, Camulodunum. It was this king who invited Roman traders and craftsmen to come and settle in Britain. Some historians attribute the origin of London to his reign (the Celtic phrase Llyn-din, “Lake-Fort” is believed by some to have given the town its name) and archaeologists state that the wooden London bridge was built at that time. The city was called Londinium, for this time when, after Caesar’s first “reconnaissance” the Romans started infiltrating into the country as immigrants and traders bringing in eastern luxuries and taking out corn, metal and slaves. Thus, ground was prepared for the Roman conquest. The decay of Roman power in Britain became apparent already at the end of the 4th century. The attacks of the wild Celtic tribes from behind the walls that had sealed off those dangerous areas, were no longer so efficiently and promptly repulsed in the latter part of the 5th century as it used to have been the Roman’s way. The usual grainloaded ships were no longer sent to the metropolis. Finally in 407 orders came for the legions to return. Those historians who base their observations on the data derived from town life, that is, the life of the romanized upper layers of the British Celts, state that Romanization was completed and the Celts forgot they were Britons. Romanization was nearly non-existent in Ireland and Scotland. In the countryside, the old Celtic way of life was preserved. The Celts continued living in their old Celtic way, suffering from the invaders’ exploitation, passing their native customs and traditions from generation to generation and speaking their Celtic dialects enriched by some of Latin words like “castra” – military camp (found now in names like Lancaster, Winchester, Leicester, Chester, etc.). The Anglo-Saxon invasion During the next some centuries there were many invasions. The Angles, Saxons and Jutes came from Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands in the 5th century, and England gets its name from this invasion (Anglelands). The Germanic tribes of the Jutes believed to have been a Frankish tribe from the lower Rhine reaches, were the first to arrive. They seem to have been in contact with the Romans and were certainly well versed in military matters since they used to serve as hired soldiers in the Roman army. They settled in the southern part of the island for good, founding their state of Kent later on. Other Germanic tribes that followed in their wake, went about the business of invasion in a very thorough fashion. They were the primitive Angles and Saxons, backward Teutonic tribes from the so-called German coast, that is from the country around the mouth of the Elbe and from the south of Denmark. The barbaric invaders not only annihilated all the remnants of Roman culture, they killed and plundered and laid the country waste. The Celts were mercilessly exterminated. One of the tribal leaders, King Arthur, organized Celtic resistance so as to make it a constant menace to the Anglo-Saxon invaders. King Arthur, the 6th c. hero of Celtic Independence, became in the memory of the people a defender of the faith. Thirteen centuries later Alfred Tennyson – a poet, described Arthur’s knights and the tragedy of the conquered people. Thus the resistance of the brave Celts protracted the conquest period, which to a great extent determined the political structure of the conquerors’ society. Up to 829 English History is the struggle waged by one of the Anglo-Saxon states after another for power over its neighbours. The Anglo-Saxon society was in transition from a stage where the family group was the basic unit to a state where the territorial unit, the village community or the township as it was called, was coming to the fore as the elementary unit of society. From the tribal organization the society was passing to the beginning of the feudal class organization. At the end of the 6th century (597) Roman Christianity was introduced. It was a process that completed later in the 7th century. 3. The influence of the invasion by Germanic tribes on the English language. The Germanic tribes who settled in Britain in the 5th century spoke the very closely related Germanic tongues of their continental homelands. From these developed the English language. In fact, the words English and England are derived from the name of one of these early Germanic peoples, the Angles. English has been spoken in England, changing gradually as languages must. Te Earliest written records of the English language are all but incomprehensible to the speaker of Modern English without special training. As soon as the Britons were left to themselves, they had very little peace for many years. Sea rovers came sailing in ships from other countries, and the Britons were always busy trying to defend themselves. Among these invaders were some Germanic tribes called Angles, Saxons and Jutes (who lived in the northern and central parts of Europe). They spoke different dialects of the West Germanic language from which modern English developed. A wild and fearless race, they came in hordes from over the North Sea and, try as they might, the Britons could never drive them away. And many battles were fought by the Britons until at last they were forced to retreat to the west of Britain: to Wales, Cornwall and Strathclyde. Those who ventured to stay became the slaves of the invaders and were forced to adopt many of their customs and learn to speak their languages. The Angles, Saxons and Jutes were pagans, that is to say they believed in many gods. The gods of the Anglo-Saxons were: Tu or Tuesco – god of Darkness, Woden – god of War, Thor – The Thunderer, and Freia – goddess of Prosperity. When people learned to divide up time into weeks and the week into seven days, they gave the names of their gods. It is not hard to guess that Sunday is the day of the Sun, Monday – the day of the Moon, Tuesday – the day of the god Tuesco, Wednesday – Woden’s day, Thursday – Thor’s day, Friday – Freia’s day, and Saturday – Saturn’s day (Saturn was the god of Time worshipped by ancient Romans). 4. The Scandinavian invasion. The Norman Conquest. Scandinavian Invasion It is impossible to state the exact date of the Scandinavian invasion as it was a long process embracing over two centuries, the first inroads of the Scandinavian Vikings having began as far back as the end of the 8th century. The Scandinavian invasion and the subsequent settlement of the Scandinavian on the territory of England, the constant contacts and intermixture of the English and the Scandinavians brought about many changes in different spheres of the English language: word-stock, grammar and phonetics. The influence of Scandinavian dialects was especially felt in the North and East parts of England, where mass settlement of the invaders and intermarriages with the local population were especially common. Norman Conquest The Norman Conquest began in 1066. The Normans were by origin a Scandinavian tribe who two centuries back began their inroads on the Northern part of France and finally occupied the territory on both shores of the Seine. The French King Charles the Simple ceded to the Normans the territory occupied by them, which came to be called Normandy. The Normans adopted the French language and culture, and when they came to Britain they brought with them the French language. The heritage of the Norman Conquest was manifold. It united England to Western Europe, opening the gates to European culture and institutions, theology, philosophy and science. The Conquest in effect meant a social revolution in England. The lands of the Saxon aristocracy were divided up among the Normans, who by 1087 composed almost 10% of the total population. Each landlord, in return for his land, had to take an oath of allegiance to the king and provide him with military services if and when required. 5. Historical background from the 12th to the 14th century. The struggle between English and French. Historical background from the 12th to the 14th century. The Norman Conquest was not only a great event in British political history but it was also the greatest single event in the history of the English language. The conquerors had originally come from Scandinavia (compare “Norman” and “Northmen”). About one hundred and fifty years before their Conquest of Britain they seized the valley of the Seine and settled in what henceforth known as Normandy. In the course of time they were assimilated by the French and in the 11th century came to Britain as French speakers and as bearers of French culture. They spoke the Northern dialect of the French language, in some minor points differing from central French. Their tongue in England is usually referred to as Anglo-Norman; for the present purpose we shall call it “French”. One of the most significant consequences of the Norman domination in Britain is to be seen in the use of the French language in many spheres of British political and social life. For almost three hundred years French was the official language of the king court, the language of the law courts, the church and the castle. It was the everyday language of the most nobles and of many townspeople in the southeast. The intellectual life and education were in the hands of French-speaking people, and boys at school were taught to translate their Latin into French instead of English. The lower classes and especially the country people, who made up the bulk of the population, held fast to their own tongue. Thus the two languages coexisted and gradually permeated each other. Translators of French books used a large number of French words in their translations and imitated the sentence structure of the original, unable to find good English equivalents. In the course of the 14th c. the English language gradually took the place of French as the language of literature and the official language of the government and ousted French from all the social spheres. Two hundred years after the Norman Conquest, in 1258, Henry II issued a Proclamation to the counsellors elected to sit in Parliament from all parts of England, in three official languages: French, Latin and English. This was the first official document after the conquest to be written in English. In 1349 it was ruled that English should be used in schools. In1362 Edward III gave his consent to an Act of Parliament ordaining that English should be used in the law courts, since “French has become much unknown in the realm”. In the same year Parliament, for the first time, was opened with a speech in English. Thus in the late 14th century English was re-established as the official language of the country. The three hundred years of domination of the French language in many spheres of life affected the English language more than any other single foreign influence before or after. The greater French influence in the south and in the higher ranks of the society led to greater dialectal differences both regional and social. A more specific influence was exercised on the alphabet and spelling. The tremendous number of French borrowings adopted by the English language indirectly affected even the phonetic structure of the language, especially word accentuation. The struggle between English and French. 1. English began to use French words in current speech. Probably many people became bilingual and had a fair command of both languages. The struggle between French and English was bound to end in the complete victory of English. The earliest sign of the official recognition of English by the Norman kings was the famous PROCLAMATION issued by Henry 3 in 1258 to the councilors in Parliament. It was written in 3 languages: French, Latin and English. During this period such changes were in English: there appeared prepositions and conjunctions, but the grammar was saved unchangeable. Such words as servant, prince, guard – (connected with life of royal families) were borrowed. With life of church – chapel, religion, prayer, to compress; with city life – city, merchant, painter, tailor. The names of animals were saved, but if their meanings were used as meal – the Norman’s names were given to them (beef, pork, veal, mutton). 2. The dialect division which evolved in Early ME was on the whole preserved in later periods. In the 14th and 15th c. we find the same grouping of local dialects: the Southern group, including Kentish and the South-Western dialects (the SouthWestern group was a continuation of the OE Saxon dialects), the Midland or Central (corresponding to the OE Mercian dialect – is divided into West Midland and East Midland as two main areas) and the Northern group (had developed from OE Northumbrian). And yet the relations between them were changing. 3. The most important event in the changing linguistic situation was the rise of the London dialect as the prevalent written form of language. The history of the London dialect reveals the sources of the literary language in Late ME and also the main source and basis of the Literary Standard, both in its written and spoken forms. The Early ME written records made in London – beginning with the PROCLAMATION of 1258 – show that the dialect of London was fundamentally East Saxon. Later records indicate that the speech of London was becoming more fixed, with East Midland features gradually prevailing over the Southern features.