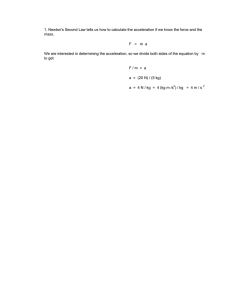

16 Newton’s Axioms The Newtonian1 or classical mechanics is governed by three axioms, which are not independent of each other: 1. the law of inertia, 2. the fundamental equation of dynamics, 3. the interaction law, and as a supplement: the theorems on independence concerning the superposition of forces and of motions. Premises of Newtonian mechanics are as follows: 1. The absolute time; that means that the time is the same in all coordinate frames, that is, it is invariant: t = t . One may determine in any coordinate frame whether events 1 Isaac Newton, b. Jan. 4, 1643, Woolsthorpe (Lincolnshire)—d. March 31, 1727, London. Newton studied in 1660 at Trinity College in Cambridge, particularly with the eminent mathematician and theologian L. Barrow. After getting various academic degrees and making a series of essential discoveries, in 1669 Newton became successor of his teacher in Cambridge. In 1672 he was member and in 1703 president of the Royal Society. From 1688 to 1705, he was also member of Parliament, since 1696 attendant and since 1701 mint-master of the Royal mint. Newton’s life’s work comprises, besides theological, alchemistic, and chronological-historical writings, mainly works on optics and on pure and applied mathematics. In his investigations on optics he describes the light as a flow of corpuscles and by this way interprets the spectrum and the composition of light, as well as the Newton color rings, diffraction phenomena and double-refraction. His main opus Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (printed in 1687) is fundamental for the evolution of exact sciences. It includes the definition of the most important basic concepts of physics, the three axioms of mechanics of macroscopic bodies, the principle of “actio et reactio,” the gravitational law, the derivation of Kepler’s laws, and the first publication on fluxion calculus. Newton also dealt with potential theory and with the equilibrium figures of rotating liquids. The ideas for the great work emerged mainly in 1665–1666 when Newton had left Cambridge because of the pestilence. In mathematics Newton worked on the theory of series, for example, in 1669 on the binomial series, on interpolation theory, approximation methods, and the classification of cubic curves and conic sections. But Newton could not remove logical problems even with his fluxion calculus that was represented in 1704 in detail. His influence on the further development of mathematical sciences can hardly be judged, because Newton disliked publishing. When Newton made his fluxion calculus public, his kind of treatment of problems of analysis was already obsolete as compared to the calculus of Leibniz. The quarrel over whether Newton or Leibniz deserved priority for developing the infinitesimal calculus continued until the 20th century. Detailed studies have shown that they both obtained their results independently of each other [BR]. 134 135 NEWTON’S AXIOMS are simultaneous, because in classical physics one may imagine that signals are being exchanged with infinitely large velocity. 2. The absolute space; that means that a coordinate frame, being at absolute rest, which spans the full space, exists. This absolute space may be thought of as being represented by the world ether, which shall be at absolute rest and so to speak embodies the absolute space. Newton by himself did not believe in the ether; he could imagine the absolute space also as being empty. In most recent time the 2.7 Kelvin radiation has been discovered. This radiation is believed to originate from the Big Bang that presumably generated our universe. A coordinate frame in which this radiation is isotropic—of equal intensity in all directions—might also serve as such an absolute coordinate frame. 3. The mass being independent of the velocity. 4. The mass of a closed system of bodies (or mass points) is independent of the processes going on in this system, no matter what kind these processes are. The concepts of absolute time and absolute space, as well as the velocity independence of the mass, are lost in the special theory of relativity. Finally, the fourth premise is no longer fulfilled in high-energy processes as, for example, p + p → p + p + π + + π − . Here new masses are generated. Newton formulated his axioms essentially as follows: Lex prima: Each body remains in its state of rest or uniform rectilinear motion as long as it is not forced by acting forces to change this state. Lex secunda: The change of motion is proportional to the effect of the driving force and tends toward the direction of that straight line along which the force is acting. Lex tertia: The action always equals the reaction, or the actions of two bodies onto each other are always of equal magnitude and of opposite direction. Lex quarta: Supplement to the laws of motion: Rule of the parallelogram of forces, that is, forces add up like vectors. Thereby the superposition principle of the actions of forces is postulated (principle of unperturbed superposition). Because we deal in the following only with point mechanics, we have to introduce the model representation of the mass point. Here one abstracts from shape, size, and rotational motions of a body and considers only its translational motion. Newton’s axioms in modern form then read as follows: Axiom 1: Any mass point remains in the state of rest or rectilinear uniform motion until this state is terminated by the action of other forces (i.e., by transfer of forces). This is a special case of the second axiom. Namely, F = 0, then −−−−→ m · v = constant. 136 NEWTON’S AXIOMS 16 Because of the presupposed velocity independece of the mass, it then holds that −−−−→ v = constant. If the “quantity of motion” p = m · v is denoted as the linear momentum of the mass point, then the law of inertia is identical with the law of conservation of the linear momentum. Axiom 2: The first time derivative of the linear momentum p of a mass point is equal to the force F acting on it: F= d(m · v) dp = = ṗ, dt dt where p = mv is the linear momentum.2 . Because in general the mass is a velocity-dependent quantity, that is, it is also timedependent, it must not simply be pulled in front of the bracket. In the nonrelativistic Newtonian mechanics (v c ; c = 3 · 108 m s−1 ), the mass m is, however, treated as being independent of the time, and one thus obtains the dynamic fundamental equation: F=m dv d 2r = m 2 = m r̈ = ma. dt dt That means that the acceleration a of a mass point is directly proportional to the force acting on it and coincides with the direction of the force. If several forces are acting simultaneously onto a mass point, then the above relation according to the principle of superposition of forces reads dp = dt n Fi . i=1 Axiom 3: The forces exerted by two mass points onto each other have equal magnitude and opposite directions; force = – counterforce: Fi j = −F ji , where i = j. Here Fi j is the force exerted by the jth point onto the ith point. F ji is the force exerted by the ith onto the jth point. Remark: The relation F = d(mv)/dt is on the one hand a definition of the force, on the other hand a law. The statutory aspect is that, for example, the first time derivative of the linear momentum occurs, but not the third or fourth or something else. Because the force 2 The time derivatives are often abbreviated with a dot, for example d f /dt ≡ f˙, v = dr/dt = ṙ, or a = d 2 r/dt 2 = r̈ We will use this notation wherever it seems appropriate. 137 NEWTON’S AXIOMS is the derivative of a vector with respect to a scalar (the time), it is a vector itself. Hence, the addition of forces is governed, for instance, by the law of force parallelogram. Problem 16.1: Single-rope pulley A weight W1 = M1 g hangs at the end of a rope. Here, g = 9.81 m/s2 is the gravitational acceleration of all bodies at the surface of the earth. At the other end of the rope, hanging over a roller, a boy of weight W2 = M2 g pulls himself upward. Let his acceleration relative to the tightly mounted roller be a. What is the acceleration of the weight W1 ? e T T Solution Let b be the acceleration of W1 and T the rope tension. The Newtonian equations of motion then read W2 A boy and a weight hanging at the ends of a rope. (a) For the mass M2 (boy): −M2 · ae = M2 g e − T e; W1 (16.1) (b) for the mass M1 (weight W1 ): M1 b e = M1 g e − T e. (16.2) These are two equations with two unknowns (T, b). Their solution may be given immediately: T = M2 (a + g); T b=g− M1 =g− = (16.3) M2 (a + g) M1 (M1 − M2 )g − M2 a . M1 (16.4) If M1 = M2 , it follows that b = −a, as it should be. On the other hand, if a = 0, it follows that 2) b = (M1M−M g and vanishes for the case M1 = M2 , as expected. 1 Problem 16.2: Double-rope pulley A mass M1 hangs at one end of a rope that is led over a roller A (compare the figure). The other end carries a second roller of mass M2 , which in turn carries a rope with the masses m 1 and m 2 fixed to its ends. The gravitational force is acting on all masses. Calculate the acceleration of the masses m 1 and m 2 , as well as the tensions T1 and T in the ropes. 138 Solution NEWTON’S AXIOMS We introduce the unit vector e ⊥ pointing upward (see figure) and denote the string tensions by T = T e and T1 = T1 e, respectively (see figure). The individual masses are influenced by the string tension (i.e., the force in the rope) and by the gravitational force. We now write down the equations of motion for the individual masses according to Newton’s fundamental law. M1 a1 e = −M1 ge + T e , A M1 m 1 (a2 − a1 )e = −m 1 ge + T1 e , m 2 (−a2 − a1 )e = −m 2 ge + T1 e . T T M2 −M2 a1 e = −M2 ge + T e − 2T1 e , (16.5) 16 T1 m2 T1 m1 The acceleration of the mass M1 has been denoted by a1 e, e that of the mass M2 is then (because of the constant rope length) −a1 e; the acceleration of the mass m 1 relative to the Masses and forces at the doublemass M2 is a2 e, that of the mass m 2 is −a2 e. 16.5 represents rope pulley. a set of four equations with the four unknowns: a1 , a2 , T, T1 . Subtraction of the second equation from the first one yields (M1 + M2 )a1 = −(M1 − M2 )g + 2T1 . (16.6) The addition of the last two equations of 16.5 leads to −(m 1 + m 2 )a1 + (m 1 − m 2 )a2 = −(m 1 + m 2 )g + 2T1 . (16.7) The subtraction of 16.7 from 16.6 then yields a relation between a1 and a2 : (M1 + M2 + m 1 + m 2 )a1 − (m 1 − m 2 )a2 = (−M1 + M2 + m 1 + m 2 )g . (16.8) A second relation of this kind is obtained by subtracting the last two equations 16.5 from each other, namely −(m 1 − m 2 )a1 + (m 1 + m 2 )a2 = −(m 1 − m 2 )g . (16.9) The accelerations a1 and a2 are now found from equations 16.8 and 16.9: a1 = −M1 (m 1 + m 2 ) + M2 (m 1 + m 2 ) + 4m 1 m 2 g; (m 1 + m 2 )(M1 + M2 ) + 4m 1 m 2 (16.10) a2 = −2M1 (m 1 − m 2 ) g, (m 1 + m 2 )(M1 + M2 ) + 4m 1 m 2 (16.11) such that the total acceleration of mass m 1 is obtained as a2 − a1 = −M1 m 1 + 3M1 m 2 − M2 (m 1 + m 2 ) − 4m 1 m 2 g (m 1 + m 2 )(M1 + M2 ) + 4m 1 m 2 (16.12) and that of mass m 2 is (−a2 − a1 ) = M1 (3m 1 − m 2 ) − M2 (m 1 + m 2 ) − 4m 1 m 2 g. (m 1 + m 2 )(M1 + M2 ) + 4m 1 m 2 (16.13) 139 NEWTON’S AXIOMS If all masses were identical (M1 = M2 = m 1 = m 2 ), then 1 a2 − a1 = − g, 2 a2 = 0, and 1 1 −a2 − a1 = − g, a1 = g, (16.14) 2 2 as one would expect. The string tension T1 follows with 16.10 from equation 16.6 after a simple calculation as T1 = = 1 1 (M1 + M2 )a1 + (M1 − M2 )g 2 2 4m 1 m 2 M1 g. (m 1 + m 2 )(M1 + M2 ) + 4m 1 m 2 (16.15) The rope tension T is obtained from the first two equations 16.5, using 16.10 and 16.15, as (M1 − M2 )a1 (M1 + M2 )g + + T1 2 2 = M1 a1 + M1 g = M1 (a1 + g) 2(m 1 + m 2 )M1 M2 + 8m 1 m 2 M1 g. = (m 1 + m 2 )(M1 + M2 ) + 4m 1 m 2 T = (16.16) According to 16.15 the rope tension T1 vanishes if one of the masses m 1 , m 2 , M1 vanishes. In this case the rope is rolling without tension, as is clearly expected. The rope tension T vanishes if either M1 = 0, or M2 and one of the masses m 1 or m 2 (or both) vanish. If m 1 = m 2 = m = 0 and if M1 = 0, M2 = 0, a limit m → 0 can be taken: T = 2M1 M2 g. M1 + M2 This is the rope tension in the case of the single roller with the two masses M1 and M2 at the rope ends.