Layoffs, Commitment, and Performance: A Sociology Study

advertisement

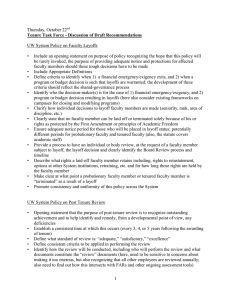

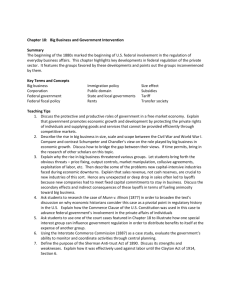

Work http://wox.sagepub.com/ and Occupations Surviving Layoffs: The Effects on Organizational Commitment and Job Performance LEON GRUNBERG, RICHARD ANDERSON-CONNOLLY and EDWARD S. GREENBERG Work and Occupations 2000 27: 7 DOI: 10.1177/0730888400027001002 The online version of this article can be found at: http://wox.sagepub.com/content/27/1/7 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Work and Occupations can be found at: Email Alerts: http://wox.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://wox.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://wox.sagepub.com/content/27/1/7.refs.html >> Version of Record - Feb 1, 2000 What is This? Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg WORK AND et al.OCCUPATIONS / SURVIVING LAYOFFS This article tests the hypotheses that the effects of layoffs on surviving employees’level of organizational commitment and job performance will vary according to (a) how close employees are to the layoffs, (b) their perceptions of the fairness of the layoffs, and (c) their position in the organizational hierarchy. Analyses were conducted on 1,900 respondents employed by a large U.S. company. Results indicated that although perceptions of layoff unfairness were associated with lower commitment regardless of employee position, close contact with layoffs was associated with the greater use of sick hours by surviving managers and professionals, but with lower use of sick hours and higher work effort by employees in lower positions. Surviving Layoffs The Effects on Organizational Commitment and Job Performance LEON GRUNBERG RICHARD ANDERSON-CONNOLLY University of Puget Sound EDWARD S. GREENBERG University of Colorado, Boulder A wave of corporate restructuring has swept American corporations over the past decade (Cappelli et al., 1997), reaching almost floodtide levels after the publication of Hammer and Champy’s (1993) Reengineering the Corporation. A central aspect of this corporate restructuring has been the intentional shedding of large numbers of employees in a process that has come to be known as downsizing (Freeman & Cameron, 1993). The evidence suggests that this downsizing is affecting large numbers of employees1 (Cappelli et al., 1997) and producing a range of negative attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Authors’ Note: This research is supported by grant No. AA10690-02 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to thank Sarah Moore, two anonymous reviewers, and the editor for their helpful comments. WORK AND OCCUPATIONS, Vol. 27 No. 1, February 2000 7-31 © 2000 Sage Publications, Inc. 7 Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 8 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS It has been suggested, for example, that downsizing is putting into doubt the unwritten yet implicit psychological contract that underlay the postwar employment system in large, core firms (Cappelli et al., 1997; Edwards, 1979). The sense of reciprocal obligation, whereby companies rewarded their employees with long-term job security in exchange for loyalty, commitment, and full work effort, is being replaced by a more fragile and contingent relationship (Morrison & Robinson, 1997). Research also indicates that downsizing has had serious adverse consequences for the many working Americans who lost their jobs during these episodes, with evidence of declining incomes, psychological deterioration, alcohol abuse, and family tensions (“The Downsizing of America,” 1996; Kozlowski, Chao, Smith, & Hedlund, 1993). Less is known, however, about layoff survivors, the vast majority of Americans who, while retaining their jobs, have found themselves working for companies where substantial layoffs have occurred. In this article, we focus on this somewhat neglected group of working Americans and examine the effects of their layoff experiences on their sense of loyalty or commitment to their employer and on their job performance. RESEARCH ON LAYOFF SURVIVORS Recent comprehensive reviews of the literature have found the impact of layoffs on survivors to have been more negative than positive (Kozlowski et al., 1993). As expected, survivors tend to be angry; less productive; less trustful of their work organizations, supervisors, and managers; more anxious about their jobs and financial futures; less likely to innovate and take risks; and more likely to suffer from low morale and job dissatisfaction (also see Mone, 1994; Sadri, 1996; Shaw & Barret-Power, 1997; Tombaugh & White, 1990). They also seem to have more health problems (Kanter, 1997; Vahtera, Kivimaki, & Pentti, 1997). However, as Brockner and his associates have shown, survivors’ reactions are not uniform. Employees’ responses to layoffs seem to vary according to how close the survivors are to those laid off, how they assess the fairness of the organization’s behavior in the layoff process (Brockner, Grover, Reed, DeWitt, & O’Malley, 1987), the survivors’ prior level of identification with the organization (Brockner, Tyler, & Cooper-Schneider, 1992), their level of self-esteem (Brockner, Davy, & Carter, 1985), and their sense of job insecurity (Brockner, Grover, Reed, & DeWitt, 1992). Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 9 Although suggestive, the existing studies on layoff survivors are marked by several limitations. Many are based, for example, on in-depth interviews with very small numbers of people in single companies, thus making it hard to generate systematic, generalizable knowledge (Grunberg, Knudsen, & Greenberg, 1997; Kets de Vries & Balazs, 1997; Noer, 1993), or on laboratory experiments conducted on undergraduate students, a study population rather different from the kinds of people and work settings involved in realworld layoffs (Brockner & Greenberg, 1990). The few existing survey-based investigations are characterized by small sample sizes (Armstrong-Stassen, 1993; Davy, Kinicki, & Scheck, 1991; Mone, 1994; Tombaugh & White, 1990), making it very difficult to specify and test elaborate models. Very few studies have examined the effects of layoffs on survivors’ job performance, and those that have have either been conducted in the artificial environment of the laboratory (Brockner et al., 1987) or have relied solely on self-report measures (Brockner, Grover, et al., 1992). Moreover, very little systematic research exists on how layoffs affect different groups of employees across the organizational hierarchy (ArmstrongStassen, 1993). This is particularly germane as recent layoff activity has gone beyond the traditional blue-collar victims and begun to affect relatively privileged and previously insulated employees such as managers and professionals (Cappelli et al., 1997, pp. 68-69). Whether such relatively privileged employees react to downsizing episodes by remaining loyal to their companies (Heckscher, 1995) or by feeling a stronger sense of betrayal because their supposed high level of prior commitment is violated (Brockner, 1992; Cappelli, 1992) is an important question for the continued viability of traditional models of corporate organization, which depend on bureaucratic control and internal labor markets (Edwards, 1979). This article aims to build on the existing research on layoff survivors and to address some of the limitations we have discussed above. In particular, we wish to examine the effects that two critical conditions of the layoff experience may have on the degree of employees’ commitment to their company. We ask to what extent employees’ organizational commitment is affected by differences in their own experiences with layoffs and in their evaluations of the fairness of their company’s behavior during the layoff process. We ask further about the extent to which these experiences, perceptions, and attitudes translate into actual behavioral outcomes, such as absenteeism and lower work effort. These questions are investigated using a large sample of employees, paying particular attention to the differential experiences of employees who occupy different positions in the organizational hierarchy. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 10 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS ARGUMENT AND HYPOTHESES ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT This study assumes that there will be significant variations in how layoffs are experienced by surviving employees and that these variations will matter in predicting survivors’ job attitudes and performance. Our fieldwork revealed considerable variation in survivors’ experiences with layoffs. We found that some employees had themselves been laid off in the past and then rehired, whereas others had been put on notice that they were next on the list to be let go, should additional rounds of layoffs occur. Some had avoided such direct experiences with layoffs but had witnessed the layoffs of close work friends or colleagues. A few unfortunate employees had experienced several of these occurrences, whereas others had experienced none of them. Thus, the contact with layoffs may be directly personal, as when employees are laid off and subsequently rehired or receive “warn notices”; or the contact may be more indirect, as happens when those with social ties to the survivors are laid off (i.e., close friends or coworkers at the firm). Although any contact with layoffs is likely to increase survivors’ sense of job insecurity and to decrease their morale and commitment to their company, we suspect that direct experiences with layoffs are likely to have stronger effects on employees than indirect ones. Another likely source of variation is how employees evaluate the fairness or justice of their company’s layoff activity. Research has shown that employee perceptions concerning procedural justice issues are important factors influencing employees’ evaluations of their organizations (McFarlin & Sweeney, 1992; Rousseau & Tijoriwala, 1998). We, therefore, expect those who perceive the layoff process as having been conducted in an unfair manner to have more negative attitudinal and behavioral reactions than those who believe the company acted fairly (Brockner, Tyler, et al., 1992). Previous research and our own fieldwork among layoff survivors indicate that employees attend to two principal factors when assessing the relative fairness of company behavior during layoffs: first, how fair the company decision process is in selecting employees for layoffs (decisions based on connections or friendship were often seen as “political” and unfair); and second, whether those who were let go were treated well by the company (Brockner & Greenberg, 1990). We also expect that the employee’s position in the organization will affect how layoffs shape organizational commitment. Those higher up in the organization are typically those who are most favored in terms of material Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 11 rewards, authority, and autonomy and therefore tend to be the most committed to the organization (Lincoln & Kalleberg, 1990). They are also more likely to have internalized the goals and values of the company (Edwards, 1979). If, as Brockner, Tyler, et al. (1992) argue, “employees’ attitudes depend on the relationship between prior belief and subsequent experiences” (p. 259), then the layoff experience should be most disturbing for those who had identified most closely with the organization, namely managers and professionals. Similarly, we expect those at the bottom of the organizational hierarchy, who are typically afforded little autonomy, authority, and trust by the organization and who receive fewer material rewards, to feel less “betrayed” or violated by the layoffs and to respond less negatively. Based on this discussion, we propose the following set of hypotheses, which address the effect of the two layoff variables on the organizational commitment of layoff survivors: Hypothesis 1a: Greater contact with layoffs will be associated with lower levels of organizational commitment. Hypothesis 1b: Greater perceived unfairness of layoffs will be associated with lower levels of organizational commitment. Hypothesis 1c: Layoff contact will have a stronger negative association with organizational commitment for managers and professionals than for employees lower down the organizational hierarchy. Hypothesis 1d: Perceived unfairness will have a stronger negative association with organizational commitment for managers and professionals than for employees lower down the organizational hierarchy. In sum, the first two hypotheses claim that layoffs should have a negative impact on all employees, whereas the second two propose that the negative effects will be even greater for the employees in the highest positions. JOB PERFORMANCE Although there is a growing body of literature on the psychological effects of layoffs on survivors’ attitudes, there has been very little research on survivors’ job performance. Surveys of companies that have downsized indicate that, although morale has clearly been harmed, this low morale has rarely damaged company performance (Greenberg & Canzoneri, 1996). Indeed, many companies report improvements in productivity (Cappelli et al., 1997). Cappelli and his colleagues speculate that survivors “cannot act out their frustration with the break in the psychological contract” (p. 201) because such behavior is extremely risky in a loose job market. Although there may be some validity to this argument, we will argue that the impact on individual Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 12 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS performance will vary depending on the amount of autonomy or power employees enjoy within the organization as well as on their options in the labor market (Schellenberg, 1996). In this article, we examine two aspects of performance over which employees have some control: (a) absences, of which a significant portion is probably not due to illness but rather is volitional in nature (Hackett, 1989; Hammer & Landau, 1981); and (b) the employee’s level of work effort (Hodson, 1991). We argue that both layoff contact and the perceived justice of the company’s behavior during the layoff process will affect these performance measures but that their impact will vary according to the employee’s position in the organizational hierarchy. Although layoffs may produce a sense that the psychological contract between employer and employee has been violated and may generate a desire to restore equity or balance in the relationship through a decline in individual performance (Adams, 1965), it is important to remember that this psychological outcome operates within an organizational structure that provides differential opportunities and constraints for translating psychological states into behavior (Walsh & Tseng, 1998). The most important structural cleavage, we argue, is the occupational one between managerial and professional employees (such as accountants, lawyers, and the like), on one hand, and lower-ranking employees, on the other. Employees lower down the organizational hierarchy, who tend to have fewer market options should they be laid off and who tend to be more closely supervised and monitored, are less likely to engage in risky behavior (such as absences or reduced work effort), no matter what their feeling is toward the company (Bowles, Gordon, & Weisskopf, 1983). Indeed, the threat of job loss, which may become more powerful the more contact employees have with layoffs, may actually lead to declines in absence behavior and increases in work effort during and following large-scale layoffs. Such workers have a strong incentive to keep their heads down and not draw attention to themselves. There are several additional reasons why lower level employees may respond to layoffs with increases in their work performance relative to upper level employees. For one thing, they are subject to closer supervision and performance measurement so they are less able than others to shirk. They are also more likely to be uncredentialed, with very job-specific skills, and therefore to have fewer opportunities in the external job market than upper-level employees. Typically, they also receive less generous severance pay and job search assistance than upper level employees (Brockner, 1992), increasing both the expected decrease in income after a layoff and the expected time spent unemployed. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 13 Finally, we note that the wage premium, that is, the gap between current wages and those prevailing on the local labor market, paid to production workers, is higher than the premium paid to upper level workers for this particular firm.2 Therefore, the cost of job loss may be much higher for production workers than for managers and professionals (Bowles et al., 1983). In contrast to lower level workers, managers and professionals face a different set of opportunities and constraints. Because they are not as closely monitored, they can respond to company layoffs with greater absences and lower levels of work effort without drawing attention to themselves or incurring disciplinary sanctions. Furthermore, they may be in a better position because of their credentials and skills to find other acceptable employment. We expect, therefore, that position in the organizational hierarchy will moderate the effects of layoff contact on absences and work effort. Whether organizational position also moderates the effects of layoff fairness on work performance is less clear. Although employees may expect that improved performance could spare them from being laid-off when the layoff is seen as having been conducted fairly, there may be less reason to believe that improvements in individual performance will enable them to escape a layoff when the layoffs are perceived as having been unfairly or arbitrarily carried out. Therefore, we expect perceived unfairness to harm performance across all job categories, but to a greater extent for managers and professionals, as they face fewer constraints in determining their level of work performance. Our argument then suggests a second set of hypotheses for job performance: Hypothesis 2a: For managerial and professional employees, greater contact with layoffs will be associated with higher levels of absences. Hypothesis 2b: For managerial and professional employees, greater contact with layoffs will be associated with lower levels of work effort. Hypothesis 2c: For lower level employees, greater contact with layoffs will be associated with lower levels of absences. Hypothesis 2d: For lower level employees, greater contact with layoffs will be associated with higher levels of work effort. Hypothesis 2e: Across all job categories, greater perceived unfairness of layoffs will be associated with higher levels of absences. Hypothesis 2f: Across all job categories, greater perceived unfairness of layoffs will be associated with lower levels of work effort. Hypothesis 2g: The magnitude of the effect of perceived unfairness on absences will be larger for upper level employees than for lower level employees. Hypothesis 2h: The magnitude of the effect of perceived unfairness on work effort will be larger for upper level employees than for lower level employees. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 14 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS METHODS STUDY SITE This study was conducted in a very large manufacturing division of a company on the west coast of the United States.3 At the time of the study (mid1996 to early 1997), the division employed more than 80,000 people who worked at every level in the job skill hierarchy, ranging from design engineers to semiskilled assemblers, from managers and lawyers to receptionists. The division operates in an industry subject to cyclical fluctuations in demand. As we began our study, the division was just completing a 5-year process of layoffs that had reduced the workforce by 27%. These layoffs coincided with the strong economic recovery from the 1991 to 1992 recession, both nationally and regionally, with unemployment in the metro region declining from 7% in 1992 to 3.5% in 1997. The layoffs were distributed across all job categories (known as pay codes in the organization) in rough proportion to each pay code’s representation in the company. For example, the drop in the number of employees between the peak of the cycle in January 1992 and its trough in January 1996 was 29% for hourly production workers and 26% for managers. Thus, hourly workers made up 49% of the labor force in 1992 and 47% in 1996. The proportion of managers remained constant at 10%. We should also note that the vast majority of the layoffs were involuntary, although some employees did subscribe to 4 a voluntary buy-out program offered by the company. In addition, many employees who were not laid off received warn notices notifying them that they might be laid off, should further workforce reductions prove necessary.5 The company undertook the layoffs both as a response to a decline in market demand and in an attempt to restructure the design and production process. The restructuring program included conversion to a computerized and streamlined design and parts-ordering system, the introduction of lean manufacturing modeled on the Toyota system (Womack, Jones, & Roos, 1990), and experiments with cross-functional teams in certain areas and product lines. Although the division’s orders were growing rapidly and workers were being hired in large numbers in early 1997, morale among the workforce was 6 still very low. Many employees believed the company had undertaken unnecessarily large reductions, despite current profitability, as a way to drive up the company’s stock price—and hence the value of top management’s stock options—and as a way to cow the labor force. Even several months into the recovery and rehiring (early 1997), large numbers of employees (30% to Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 15 40% of the sample) reported, in answer to a question on the survey, that they believed their jobs would be put at risk in the future by various aspects of restructuring (e.g., lean production, new technologies, or outsourcing). DATA COLLECTION Both the company and the two unions, which together represent about 70% of the labor force, cooperated in the study. The company allowed us to examine important documents and statistical information, giving us access to key policy makers and to employees, on condition of complete confidentiality. The two unions agreed to let us speak to shop stewards and to advertise in union newspapers so that we could encourage widespread participation in the survey. Data were collected in three forms. First, in-depth interviews and focus groups were conducted with a randomly selected sample of about 80 employees, representing all job categories and management levels. A key purpose of these interviews and focus groups was to gain a sense of the range of workplace changes employees and managers had experienced and to assess the nature of their reactions to the layoffs and to the restructuring program. Second, a variety of data, including number of sick hours used, was collected 7 directly from company records. Finally, a questionnaire was mailed to 3,700 randomly selected and currently employed workers who had worked for the division for at least 2 years.8 Of these, 2,279 valid questionnaires were returned, representing a 62% return rate. Respondents were each paid $20 for participating. Analysis was conducted on those respondents with no missing values.9 VARIABLES The measures used in this study are either standard measures from the social science literature or were developed specifically for this study and pretested on a group of employees. One of the performance measures, sick leave hours, is taken directly from internal company records. Layoff contact experience. This additive index is original to this study and is designed to measure the degree of contact surviving employees have with layoffs. It is constructed from four questions that probe the details of respondents’ direct and indirect experience with layoffs in their present company. The questions ask respondents, all of whom were employed by the company when the survey was conducted, whether they had at any time in the past 5 Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 16 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS years (a) been laid off (and then rehired), (b) received a warn notice that they might be laid off in the next round of downsizing, or (c) had close friends at the company and/or (d) coworkers laid off. To take account of the relative severity of the layoff experience, items are weighted so that the more direct and close the contact with layoffs was, the greater the weight. We assume that direct personal contact with layoffs is likely to have more powerful effects on the survivors’sense of vulnerability to job loss and on any negative emotional response to the company than witnessing the layoff of a friend or colleague. We also assume that the emotional effect of the layoff of a close friend will be stronger than that of a coworker because of the closer social ties and greater identification that exists with a close friend (Brockner et al., 1987).10 Therefore, having been laid off and rehired is scored as 4, receiving a warning about a pending layoff is scored as 3, having a friend in the company laid off is scored as 2, and having a coworker laid off is scored as 1. The resulting index ranges from 0 to 10. Sense of layoff justice. Two questions make up this additive index.11 One asks whether the respondent believes the company acted fairly in selecting those who were to be let go during the last round of layoffs; the other asks how well the company treated those who were let go. The measure is coded so that higher scores reflect greater perceived justice. Alpha for this index = .66. Position in the organizational hierarchy. Employees in the company are divided into six pay codes, ranging from managers, professionals, and administrators at the top, down through engineers, technicians, and general office staff to hourly production workers. We have divided these six pay codes into a dichotomous variable based on our own and company insiders’ assessments of the degree of autonomy and power each pay code has within the company. Managers, along with professionals and administrators, are in one category because they exercise power over others and/or enjoy wide latitude in deciding how to carry out their work. The other job categories—engineers, technicians, clerical, and hourly production workers—tend to be more closely supervised and to have less autonomy on the job in this company.12 Layoff Contact · Position in the Organizational Hierarchy. This interaction term allows the relationship between layoff contact and the dependent variables to differ for each organizational position. Because organizational position is a dummy variable (1 = manager or professional; 0 = other), the value of this variable will equal the value of layoff contact for managers and professionals and will equal 0 for everyone else. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 17 Sense of Layoff Justice ´ Position in the Organizational Hierarchy. As with the preceding interaction, this variable allows the effect of layoff justice to differ between the organizational positions. Organizational commitment. This three-item index measures one central component of organizational commitment, namely, how attached respondents are to the business enterprise in which they are employed (O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). The questions ask respondents to indicate their agreement or disagreement, using a 5-point Likert-type scale format, with the following statements: “I feel very little loyalty to this company”; “I am proud to work for this company”; “I would turn down another job with more pay in order to stay with this company.” This is a shortened version of the scale used by Lincoln and Kalleberg (1990) and has an alpha of .72. Individual job performance. We employ both an objective and a selfreport measure to assess the performance effects of the layoff experience. Sick leave hours is one of the few company-recorded indicators of individual absenteeism and measures the total number of hours each employee has used from his or her sick leave account. Because employees across all the pay codes receive the same 2 weeks of paid sick leave hours per year and because all employees have a similar incentive to economize on the hours used (unused sick leave hours are returned to employees in some form of money payment), variations in the hours used across individuals or pay codes is a useful indicator of both voluntary and involuntary absences. The measure we use in the analysis represents the hours used over 30 months prior to the study (July 1, 1994 to December 31, 1996) and hence captures absence behavior during and just after the height of the layoff activity. The second measure is original to this study and asks respondents to estimate the proportion of each day that they work to their full potential (answer categories include the following: nearly all the time: i.e., 90% or more, most of the time, i.e., 75% to 90%, some of the time, i.e., 50% to 75%, not much of the time, i.e., less than 50%). The question taps into another dimension of performance; namely, the effort employees expend when they are in attendance at work. Of course, the question assumes that technical aspects of work organization do not severely constrain the ability of employees in different pay codes to determine their effort levels. Although it is true that some production jobs may provide very little opportunity for individuals to control their work effort (e.g., assembly line work), in this division there was no moving assembly line. The product moved from station to station, but the flow was not machine-paced. Similarly, we recognize that effort norms may be the Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 18 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS result of explicit or implicit collective decisions of teams or groups (Barker, 1993), and this may constrain individual choices regarding work effort. Although in this division, teams were more prevalent at the higher levels of the organization, there was absolutely no difference in the average effort levels reported by those in higher and lower level positions (both scoring 2.94 on the full potential variable). These observations, as well as the feedback we received in a pretest of the question and the response categories, convinces us that the question is a reasonably valid indicator of individuals’ perceived work effort across all positions in the organization. Control variables. We employ a large number of controls so we can better assess the independent effects of the two layoff variables. In addition to the standard background variables of age, gender, time worked at the company, family income, and whether the respondent is married or living with a partner and has children under 18 living at home, we also control for a number of important attitudinal variables that have been linked to organizational commitment, absences, or work effort in the literature. These are job challenge, job satisfaction, organizational support, work stress, role overload, and the respondents’ sense of mastery (Brooke & Price, 1989; Lincoln & Kalleberg, 1990; Mayer & Schoorman, 1998; Mowday, Porter, & Steers, 1982). To control for the possibility that organizational restructuring is responsible for changes in work performance, we include a measure of the total amount of change an employee has experienced due to reengineering. Finally, to better assess the effects of the layoff variables on voluntary absence behavior (as opposed to involuntary absences due to illness), we have added a control for the number of symptoms of bad health respondents report (see Appendix for details of the items in the various control measures). RESULTS Table 1 provides the ranges, means, and standard deviations for the variables used in the analysis. Table 2 presents the results of ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions, with commitment and the two performance measures regressed separately on the control variables and the study variables described in the previous section. From column 1, we see that the perceived fairness of the layoffs has a highly significant association with commitment, indicating that the greater the perception of company fairness by employees, the greater their level of organizational commitment. The result is consistent with Hypothesis 1b. To test Hypothesis 1d, the claim that the response of upper level employees to Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS TABLE 1: 19 Descriptive Statistics of Variables Included in the Regression Analyses Mean Range Organizational commitment 10.04 Sick hours 103.37 Full potential 2.94 Layoff contact 2.51 Layoff justice 3.71 Organizational position (1 = manager/professional) 0.27 .57 Layoff contact organizational position Layoff justice organizational position 1.00 Job challenge 10.31 Organizational support 10.35 Mastery 26.24 Role overload 9.41 Age 43.60 Gender (0 = male) 0.24 Tenure with company 14.55 Married/partner 0.77 Children 0.48 Family income 3.73 Stress 10.80 Job satisfaction 11.24 Bad Health Index 1.81 Reengineering change 51.25 3-15 0-624 1-4 0-10 0-6 ´ ´ 0-1 0-10 0-6 3-15 4-20 8-35 3-15 24-93 0-1 0-42 0-1 0-1 1-7 0-18 3-15 0-6 14-70 SD n 2.50 58.88 0.77 1.90 1.40 2,229 2,262 2,246 2,262 2,130 .45 1.22 1.83 2.67 3.61 4.71 2.63 8.72 0.43 7.17 0.42 0.50 1.55 5.91 2.37 1.24 7.96 2,262 2,262 2,235 2,236 2,241 2,213 2,245 2,248 2,252 2,262 2,225 2,228 2,201 2,172 2,238 2,217 2,119 perceived unfairness will be more negative than the response of lower level employees, we must examine the value and significance of the coefficient of the interaction term of perceived fairness and organizational position.13 We see that the interaction term between perceived fairness and organizational position is quite small and statistically insignificant, indicating that perceived fairness has a similar effect on all employees, no matter what their position in the organization. Contrary to our expectations specified in Hypotheses 1a and 1c, layoff contact does not have a significant negative impact on commitment for any group of employees. Finally, several of the control variables, age, job tenure, job challenge, and organizational support, have the expected significant effects on commitment. In column 2, we see that sick hours are significantly related to layoff contact. The coefficient for layoff contact without the interaction term indicates that higher levels of layoff contact are significantly associated with reduced sick hours for lower level employees, supporting Hypothesis 2c. The Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 20 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS TABLE 2: OLS Regressions for Commitment, Sick Hours, and Full Potential Dependent Variable Independent Variable Layoff contact Layoff justice Organizational position Layoff contact × organizational position Layoff justice × organizational position Organizational commitment Job challenge Organizational support Mastery Role overload Age Gender Tenure with company Married/partner Children Family Income Stress Job satisfaction Bad Health Index Reengineering change Constant n R2 (1) Organization Commitment (2) Sick Hours (3) Full Potential 0.050 (0.027) –2.144** (0.816) 0.023* 0.242*** (0.041) –2.163 (1.247) 0.006 0.042 (0.360) –27.54* (10.84) 0.036 –0.055 (0.065) 5.366** (1.950) –0.017 (0.010) (0.016) (0.138) (0.025) –0.015 (0.028) (0.074) 2.946 (2.228) –0.029 –1.594* (0.776) –0.653 (0.638) 0.636 (0.506) 0.452 (0.318) –0.376 (0.635) –0.564** (0.203) 25.922*** (3.363) –0.211 (0.245) 5.121 (3.814) 0.781 (3.074) –4.669*** (1.043) –0.205 (0.280) –1.309 (0.861) 4.498*** (1.154) 0.606** (0.200) 2.543*** (0.471) 139.23*** (16.458) 1,951 1,759 0.39 0.10 0.168*** (0.019) 0.288*** (0.015) 0.015 (0.010) –0.029 (0.018) 0.028*** (0.007) 0.218* (0.109) 0.034*** (0.008) –0.012 (0.126) 0.035 (0.101) –.030 (0.035) † (0.010) 0.019 0.040*** (0.008) 0.0003 (0.006) 0.017*** (0.004) 0.001 (0.008) 0.007** (0.003) 0.306*** (0.043) –0.005 (0.003) 0.103* (0.048) –0.012 (0.039) –0.036** (0.013) 0.013*** (0.004) 0.037*** (0.011) –0.017 (0.015) 0.0005 (0.003) 0.958*** (0.209) 1,748 0.14 NOTE: OLS = ordinary least squares. †p =.051. *p <.05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. interaction term is also significant, suggesting that managers and professionals differ from other workers in their response to layoff contact. In fact, based on the equation, we expect that, on average, managers and professionals will increase their sick time by 3.2 hours for each unit increase in their score on the index of layoff contact. Computing the standard error from the covariance matrix (not shown), this value is found to be significantly greater than zero ( p = 0.04). This result supports Hypothesis 2a. We do not find support for the hypotheses (2e and 2g) that relate layoff fairness and absences. The coefficient of perceived fairness does not achieve significance for either set of employees. We do find, however, that employee commitment is significantly related to sick hours, such that higher commitment is associated with fewer sick hours used. Not surprisingly, the index of Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 21 bad health has a significant positive association with sick hours, as does being female and experiencing a lot of reengineering change. Column 3 of Table 2 shows the regression for the other performance variable, working at full potential.14 Consistent with Hypothesis 2d, we find that higher scores on the index of contact with layoffs is associated with a greater propensity to report working to their full potential for lower level employees. Unlike the analysis of sick hours, the effect of layoff contact on working at full potential for upper level employees does not significantly differ from that for lower level employees. This is shown by the statistical insignificance of the interaction term. However, the magnitude of the effect, as measured by the points estimates, is much stronger for lower level employees: The coefficient of layoff contact for lower level employees is 0.023; for upper level, 0.006 ( = 0.023 – 0.017). But because the estimate of the effect for upper level employees is positive (although small), we do not find support for Hypothesis 2b. Finally, the relationship between perceived fairness of the layoffs and working to one’s full potential is small and insignificant for all employees, rejecting Hypotheses 2f and 2h. Again, as with sick hours, we find that higher commitment is associated with a greater propensity to work to one’s full potential. DISCUSSION Our purpose in this article was to examine the effects of two important aspects of layoffs on the organizational commitment and job performance of a large group of employees in different positions of authority in a large manufacturing company. We find mixed support for the hypotheses relating the two layoff variables to organizational commitment. Only Hypothesis 1b, which predicts a negative association between perceptions of layoff unfairness and organizational commitment, is supported. No support is found for the hypothesized negative association of layoff contact with commitment (Hypothesis 1a), nor for a differential effect of either layoff variable on the commitment of managers and professionals in contrast to employees lower down the organizational hierarchy (Hypotheses 1c and 1d). The result that perceived layoff unfairness has a strong, significant, and negative impact on organizational commitment, given the control that is present for other relevant work variables, for example, job challenge and organizational support, can plausibly be interpreted as supportive of our theoretical proposition— when workplace norms are violated through what is perceived to be an unjust layoff process, workers respond by decreasing their commitment to the organization. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 22 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS We suggest two possible explanations for the lack of support for Hypothesis 1d, that managers and professionals would respond more strongly to perceived layoff injustice than lower level employees. One is that norms of justice are equally strong across the organization. Even though organizational commitment seems to be more essential to obtain adequate performance from managers and professionals, workers in other positions in the organization can often be as committed to the organization and can respond as strongly to violations of the norms of workplace justice. In addition, at certain critical times, such as when companies engage in large-scale layoffs, all workers, regardless of their organizational position, may be reminded that they are vulnerable to someone else’s decision. Perhaps for similar reasons, we did not find support for the claim that layoff contact would be associated with reduced employee commitment to the organization (Hypothesis 1a). Layoff contact, controlling for the perceived fairness of the layoff, may not diminish commitment because workers may expect such behavior in the modern economy. In response to the recent widespread and continuous downsizing and restructuring activity, workers may have learned to regard layoffs as a normal element of a competitive marketplace and thus no longer see them as violating the implicit reciprocal obligations of the psychological contract. Indeed, the postwar contract may no longer be shaping many employees’ expectations. However, the perception of the justice of the layoff is not dictated by competitive marketplace pressures, and employees seem unwilling to commit to the organization when it appears to be acting unfairly. The fact that employees in all occupational groups in the organization respond strongly to normative violations would explain the unexpected statistical insignificance of the interaction term for layoff contact and employee position in the organization. We believed that managers and professionals would have a more negative response to layoff contact. It seems that many employees at this level of the organization also have learned to accept downsizing as an inescapable fact, controlling for the manner in which it was conducted. Heckscher (1995) found such a result for middle managers, who reported that they believed downsizing to be necessary and did not reduce their loyalty to the firm in its wake. Turning to the effects of the two layoff variables on work performance, we again find mixed support for our hypotheses. Whereas the perceived fairness of the layoff seems to affect employee commitment, the degree of contact with layoffs seems to matter in the case of employee job performance. As hypothesized (2a and 2c), we find that the work performance of employees does not respond uniformly to contact with layoffs. For employees in engineering, technical, clerical, and production positions in the organization, Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 23 greater layoff contact is associated with lower use of sick hours. On the other hand, for managers and professionals, greater contact with layoffs tends to be associated with higher use of sick hours. This result is significant, even with a large number of controls entered for other variables that might influence absences. Indeed, the inclusion of the symptoms of poor health variable as a control increases the likelihood that the sick hours that are being predicted are not primarily due to ill health (including ill health that might have been 15 caused by the stresses associated with layoffs). It should also be remembered that all employees are allocated an equal number of sick hours and have similar financial incentives to economize on their use. So what explains the divergent behavior of these two groups of employees? As we have argued, we suspect that the behavior of lower level employees may represent a rational response to their perceived threat of job loss. With less authority and autonomy in the organization than managers and professionals, and with fewer options in the job market, these workers may seek to change their behavior (for example, by reducing their absences) so as to minimize their chances of being selected for layoffs in any future rounds of downsizing. This interpretation gains some support from the findings in a recent longitudinal study of the effects of downsizing on absenteeism. Whereas downsizing increased the rate of medically certified long-term sick leave, it reduced short-term absences not related to ill health (Vahtera et al., 1997). Similarly, our findings that lower level employees with the greatest contact with layoffs report that they are more likely to work to their full potential throughout the day bolster this interpretation. The behavior of managers and professionals who have had the greatest contact with layoffs (higher absences but no noticeable effect on their selfreported work effort) does not seem to indicate a retributive or hostile reaction. If that were the case, as we hypothesized, then we should see particularly steep declines in their levels of organizational commitment and in their self-reported levels of work effort. Neither is evident. This suggests that the greater use of sick hours by managers and professionals may be due to jobsearch behavior. We speculate that such employees, when they see impending layoffs, use the greater freedom from supervision their positions provide and the marketability of their skills to begin to absent themselves from work in the search for alternative employment (Drago & Wooden, 1992; Mowday et al., 1982, p. 91). This interpretation was supported by several managers at 16 the company who were asked to comment on the findings. Employees’ perceptions of the fairness of the layoffs has no direct or main effect on either of the performance measures, nor do we find an interaction effect with the employees’ position in the organization. Whatever effect layoff fairness has on performance is mediated through the effect on Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 24 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS organizational commitment and is similar for all job categories in the organizations. Perceptions of unfairness are associated with lower organizational commitment, and lower commitment is associated with increased absences and reduced work effort. It appears, therefore, that layoffs can affect survivors’ individual job performance in two ways. Contact with layoffs seems to improve lower level employees’ work performance, at least in the short run, whereas it seems to have either little or a negative effect on higher level employees. Perceptions of layoff unfairness worsen employee performance by lowering commitment across all positions in the organization. CONCLUSION Although our study has sought to address some of the weaknesses of previous research in this area, it is still marked by several limitations. First, even though the sample was large and occupationally heterogeneous, our results are based on a sample of employees in only one company, and therefore the question of generalizability is raised. We make no definitive claims about the effects of layoffs on survivors across the whole U.S. economy. We believe, however, that what is going on in this firm in terms of outsourcing, downsizing, digitalization of design and manufacturing, and lean production is fairly typical of what is going on in large manufacturing firms across the country and that our findings may be cautiously extended to this economic sector. Whether this is a valid assumption must, however, await further research on other companies in other industries. Second, it is possible that some of the reported relationships may be bidirectional, or the product of third unmeasured variables. For example, organizational commitment may influence perceptions of unfairness, and the relationship between commitment and work effort may be the result of a general positive effect. Similarly, job performance may have influenced who was selected for layoffs, with work sections with the worst performance singled out for the most layoffs. Although it is plausible to argue that there was such a selection process at work for those who received warn notices, or even perhaps for those who had close colleagues laid off, it is highly unlikely that the company selected layoff victims based on their friends’ level of organizational commitment and job performance. So although we recognize that only longitudinal studies with baseline data can definitively untangle issues of causality, we nevertheless believe that our interpretation—that it is the layoff experiences that produced the effects—is valid. A third limitation concerns our measure of layoff contact, which does not include organizations that experienced no layoffs and therefore does not have Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 25 the total possible variation in the condition. Even those individuals who scored zero on our measure were almost certainly aware that the organization was laying off large numbers of employees and thus were somewhat affected by the experience. Studies that use a quasi-experimental longitudinal design or that include organizations with no or very few layoffs are necessary to provide a complete determination of the effects of layoff contact. However, we should note that such firms are increasingly hard to find in the manufacturing sector of the economy, as even nonunion companies, such as IBM, Kodak, and Sears, which had never previously experienced large-scale layoffs, have downsized (Jacoby, 1998). Despite these limitations, this study reinforces the prevalent notion in the literature that downsizing and large-scale layoffs have important effects on surviving employees. Moreover, the effects are evident a full 2 years after the last major round of layoffs, at a time when the company was undergoing rapid growth in sales and employment. And, even as downsizing and layoffs have become routine practices in large companies and, therefore, are no longer seen as serious violations of an implicit postwar contract, our findings suggest that employees’ sense of commitment may still be strongly affected by how the layoffs are carried out and by how those who are laid off are treated. Indeed, this new climate of job uncertainty has led some commentators to predict the emergence of a new kind of work commitment, one tied to a “mission or task rather than to a company” (Heckscher, 1995). The archetypal employee will have to become “flexible” and “emotionally detached” (Rudolph, 1998). Whether such a psychological shift is occurring is unclear at present. Future researchers might want to explore more systematically whether such contingent attachments are emerging and what their consequences are for employees and the companies that employ them (McGovern, Hope-Hailey, & Stiles, 1998). The results also shed light on the somewhat puzzling observation of low employee morale coexisting with solid or at worst mixed work performance in downsizing companies (Cappelli et al., 1997). As we have seen, not all employees face the same set of constraints and opportunities in selecting their behavioral responses. Lower level employees may feel levels of anger or demoralization similar to those in more privileged positions in the wake of layoffs; however, with less power and fewer options, they may have to swallow hard and toe the line. However, it is doubtful whether such a basis for worker effort augurs well for the long-term performance of America’s large firms. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 26 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS APPENDIX: Control Variable Variable (source) Question Age How old were you on your last birthday (in years)? Children Do any children under the age of 18 live with you in your home? (Yes/No) Gender Are you male ( = 0) or female ( = 1)? Married/partner What is your marital status? (1 = married or living with partner, 0 = other) Job tenure How long have you worked at the company (in years)? Index of Job Challenge Sum of three items: On my job I seldom get a chance to use my special skills and abilities (reverse coded); Success on my job requires all my skill and ability; My job is very challenging. 5-point Likert-type response categories from strongly disagree (SD) to strongly agree (SA). Alpha = .74 Index of General Job Satisfaction (Camman, Fichman, Jenkins, & Klesh, 1983) Sum of three items: All in all, I am very satisfied with my job; In general I don’t like my job (reverse coded); In general I like working here. 5-point Likert-type responses from SD to SA. Alpha = .86 Mastery Scale (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978) Sum of seven items: I have little control over the things that happen to me; There is really no way I can solve some of the problems that I have; There is little I can do to change many of the important things in life; I often feel helpless dealing with the problems of life; Sometimes I feel I’m being pushed around in life (all five previous items are reverse coded); What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me; I can do just about anything I really set my mind to do. 5-point Likert-type responses from SD to SA. Alpha = .82 Index of Poor Health Sum of five items asking respondents if they had experienced (Yes/No) any of the following in the last year: back pain, ulcers, indigestion, high blood pressure, heart problems. Index of Perceived Organizational Support (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchinson, & Sowa1986) Sum of four items: The company appreciates extra effort from me; The company really cares about my well-being; If I did the best job possible, the company would be sure to notice; The company cares about my opinions. 5-point Likert-type response categories from SD to SA. Alpha = .88 Index of Work Overload (Camman et al., 1983) Sum of three items: I never seem to have enough time to get everything done; I have too much work to do everything well; The amount of work I am asked to do is fair (reverse coded). 5-point Likert-type responses from SD to SA. Alpha = .76 Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 27 APPENDIX Continued Variable (source) Question Index of Stress in General (Smith et al., 1992) Respondents were asked: Think of your job in general. All in all, what is it like most of the time: pressured, hassled, pushed, many things stressful, relaxed (reverse coded). Response categories to the six items were Yes, it describes my job;No, it doesn’t describe my job;I can’t decide.Alpha = .82 Family income Measured as 1 = less than $35,000; 2 = $35,000 to $49,999; 3 = $50,000 to $64,999; 4 = $65,000 to $79,999; 5 = $80,000 to $94,999; 6 = $95,000 to $109,999, 7 = Over $110,000 Index of Amount of Reengineering change Respondent was given a general question, To what extent have you been expected to do the following things in your work over the past 2 years? The index is the sum of the Likert responses (much less to much more) for 14 aspects of work: To use your skills in new ways, To learn to use new technology, To work on new problems and tasks you haven’t done before, To upgrade your skills and training just to stay even, To work with less supervision, To take on more responsibility for setting work goals, To work with people in different job categories than your own, To work on teams, To work longer hours, To add tasks done by others in the past to your own normal responsibilities, To attend more meetings, To adopt a new organizational philosophy, To learn to use computers, To learn new software programs. Alpha = .86 NOTES 1. As late as 1996, even as the U.S. economy was in its fifth year of expansion, the American Management Association reported that job elimination continued at a pace similar to that during the early 1990s, with half of the responding firms (1,441 major U.S. firms participated in the survey) reporting job cuts and about one third engaging concurrently in hiring and firing (Greenberg & Canzoneri, 1996). 2. Indirect evidence is supportive of our contention. Company and union officials agree that production workers are paid a generous premium over prevailing wages in the local labor market, an observation confirmed by a comparison of state-gathered earnings data with the income data in our survey. In contrast, a comparison of the salary of recent MBAs at the leading business school in the area with those of recent MBA hires at the company suggests that upperlevel workers at this company are paid below the prevailing local average salary. 3. Because we do not approach this study as a case study and because of confidentiality agreements with the study company, we do not provide rich contextual detail, although we provide enough, we believe, to set our methods and findings in scientific context. Our main concern Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 28 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS in this study is not this case, moreover, but the relationship among a range of variables about jobs and the workplace. And, because the study is being conducted in a very large company with several production sites, a wide range of technologies and occupations, many supervisory styles, and a variety of forms of production organization, we are confident that wide variation exists on all of our principle variables. Thus, what we lose in broad generalizability, we believe, is compensated for by our ability to examine rich and complex relationships, with, as we have said, some confidence that our findings can be cautiously generalized to large American manufacturing firms. 4. See Cornfield (1983) for an analysis of the factors that influence the probability of voluntary and involuntary layoffs across different occupational groups. In contrast to the case reported here, Cornfield found variations in the rates of layoffs across occupational groups. 5. Large companies are required, by law, to give at least 60 days notice to employees targeted for layoffs (known as warn notices in this company). Managers admitted they handed out many more warn notices than were actually activated, thus damaging employee morale more than necessary. 6. This assessment is supported by comments from managers and union leaders, as well as by the many employees we interviewed. Evidence from internal company surveys and our survey also confirms this state of low morale. 7. About three fourths of the items in the questionnaire are validated items used by other researchers or by us in the past and are widely discussed in the research literature. The remainder are items specific to this study, formulated after interviews and focus group sessions with employees. A preliminary version of the questionnaire was pretested on a sample of 104 employees from one work sector of the larger company. A focus group, organized from among employees who had participated in the pretest, helped analyze the questionnaire. 8. This was done to exclude new hires who had not experienced the downsizing phase. 9. To assess possible bias due to missing values, missing cases were compared to the cases included in the regression. The two groups did not differ significantly, and in fact were nearly equal on a large number of variables, including demographic, job attitude, and performance measures. We also compared the sample to the division’s workforce on average age and tenure in the company and on racial and gender composition, finding no significant differences between the two groups. Specific results are available from the authors. 10. Some support for these assumptions is provided by comparing the scores of survivors who had experienced any one of these four kinds of contact with layoffs. Those with direct personal experiences reported greater job insecurity than respondents with indirect experiences. Similarly, survivors who had seen friends laid off reported feeling less trust in top management than those who had witnessed the layoff of coworkers. 11. The questions included the following: (a) During the last major round of layoffs, how fair was the procedure that the company used to select those who were let go? (b) During the last major round of layoffs, how well did the company treat those who were let go? Answer categories were very well, well, not very well, and not well at all. 12. Although we recognize that engineers occupy an ambiguous position in any organizational hierarchy because they are both highly skilled employees and yet subject to monitoring and supervision, we believe there are two good reasons why engineers can validly be distinguished from managers and professionals and placed with hourly, clerical, and technical employees. First, all the engineers are represented collectively by an association that acts like a union in all negotiations with the company. Their wages and benefits are therefore determined through collective bargaining with the company, unlike those of managers and professionals. Second, they report considerably less decision-making authority in the functioning of teams than do managers and professionals in similar situations. Still, given the ambiguous position of engi- Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 29 neers, we reran the three regressions excluding the engineers. Results for the organizational commitment and the sick hours variables were essentially unchanged except that commitment no longer had a significant effect on sick hours, whereas layoff justice reduced sick hours used. The equation for work effort was somewhat different, with layoff contact now having no effect and the significance of the commitment variable becoming borderline ( p < .10). 13. The beta coefficient for upper-level employees is obtained by summing the coefficient of perceived fairness with the coefficient of the interaction term. The variances and covariance of these latter coefficients are used to obtain the standard error of the coefficient for the upper-level employees. 14. As a reviewer noted, full potential might be better modeled using an ordered logit rather than an OLS regression. Following this approach, the results were essentially unchanged compared to those presented in Table 2; that is, increasing layoff contact is associated with increasing work to full potential for lower-level employees. We provide the OLS results instead of the ordered logit because they are more widely understood and easier to interpret. The ordered logit results are available from the authors. 15. Of course, it is certainly possible that close contact with layoffs increases the incidences of health problems in survivors in all occupational groups (Grunberg, Moore, & Greenberg, 1999). What we are suggesting is that, regardless of the possible reasons for the absences, managers and professionals find it less difficult to absent themselves from work. 16. A reviewer suggested that this interpretation would be strengthened if warn notices, rather than layoff contact, were a predictor of sick hours for managers but not other employees. Additional regression analysis (available from the authors) did find that warn notices have a significant positive association with sick hours for managers. The association with other employees was negative but failed to reach significance. REFERENCES Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic Press. Armstrong-Stassen, M. (1993). Survivors’ reactions to a workforce reduction: A comparison of blue-collar workers and their supervisors. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 10, 334-343. Barker, J. R. (1993). Tightening the iron cage: Concertive control in self-managing teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 408-437. Bowles, S., Gordon, D. M., & Weisskopf, T. E. (1983). Beyond the waste land. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books/Doubleday. Brockner, J. (1992, Winter). Managing the effects of layoffs on survivors. California Management Review, pp. 9-28. Brockner, J., Davy, J., & Carter, C. (1985). Layoffs, self-esteem, and survivor guilt: Motivation, affective, and attidunal consequences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 229-244. Brockner, J., & Greenberg, J. (1990). The impact of layoffs on survivors: An organizational justice perspective. In J. S. Carroll (Ed.), Applied social psychology and organizational settings (pp. 45-75). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Brockner, J., Grover, S., Reed, T. F., & DeWitt, R. L. (1992). Layoffs, job insecurity, and survivors’work effort: Evidence of an inverted-U relationship. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 413-425. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 30 WORK AND OCCUPATIONS Brockner, J., Grover, S., Reed, T., DeWitt, R., & O’Malley, M. (1987). Survivors’ reactions to layoffs: We get by with a little help for our friends. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, 526-541. Brockner, J., Tyler, T. R., & Cooper-Schneider, R. (1992). The influence of prior commitment to an institution on reactions to perceived unfairness: The higher they are, the harder the fall. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37, 241-261. Brooke, P. P., & Price, J. L. (1989). The determinants of employee absenteeism: An empirical test of a causal model. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62, 1-19. Camman, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, G. D., Jr., & Klesh, J. R. (1983). Assessing the attitudes and perceptions of organizational members. In S. E. Seashore, E. E. Lawler III, P. H. Mirvis, & C. Camman (Eds.), Assessing organizational change. New York: John Wiley. Cappelli, P. (1992). Examining managerial displacement. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 203-217. Cappelli, P., Bassi, L., Katz, H., Knoke, D., Osterman, P., & Useem, M. (1997). Change at work. New York: Oxford University Press. Cornfield, D. B. (1983). Chances of layoff in a corporation: A case study. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, 503-520. Davy, J., Kinicki, A. J., & Scheck, C. L. (1991). Developing and testing a model of survivor responses to layoffs. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 38, 302-317. The downsizing of America. (1996). New York: Times Books. Drago, R., & Wooden, M. (1992). The determination of labor absence: Economic factors and workgroup norms across countries. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 45, 764-778. Edwards, R. (1979). Contested terrain: The transformation of the workplace in the twentieth century. New York: Basic Books. Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchinson, S., & Sowa, D., (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500-507. Freeman, S. J., & Cameron, K. S. (1993). Organizational downsizing: A convergence and reorientation framework. Organization Science, 4, 10-29. Greenberg, E. R., & Canzoneri, C. (1996). 1996 AMA survey on downsizing, job elimination, and job creation. New York: American Management Association. Grunberg, L., Knudsen, H., & Greenberg, E. (1997). The effects of downsizing at a large American company: A qualitative investigation. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Comparative Sociology, University of Puget Sound. Grunberg, L., Moore, S., & Greenberg, E. (1999). The effects of contact with layoffs on surviving employees’ health and health-related behaviors. Unpublished manuscript. Hackett, R. D. (1989). Work attitudes and employee absenteeism: A synthesis of the literature. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62, 235-248. Hammer, M., & Champy, J. (1993). Reengineering the corporation. New York: HarperCollins. Hammer, T. H., & Landau, J. C. (1981). Methodological issues in the use of absence data. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66, 574-581. Heckscher, C. (1995). White-collar blues: Management loyalties in an age of corporate restructuring. New York: Basic Books. Hodson, R. (1991). Workplace behaviors. Work and Occupations, 18, 271-290. Jacoby, S. (1998). Downsizing in the past. Challenge, 41, 100-112. Kanter, R. M. (1997, July 21). Show humanity when you show employees the door. The Wall Street Journal. Kets de Vries, M. F. R., & Balazs, K. (1997). The downside of downsizing. Human Relations, 50, 11-50. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014 Grunberg et al. / SURVIVING LAYOFFS 31 Kozlowski, D., Chao, G. T., Smith, E. M., & Hedlund, J. (1993). Organizational downsizing strategies, interventions, and research implications. In International review of industrial and organizational psychology. New York: John Wiley. Lincoln, J. R., & Kalleberg, A. L. (1990). Culture, control, and commitment. New York: Cambridge University Press. Mayer, R. C., & Schoorman, F. D. (1998). Differentiating antecedents of organizational commitment: A test of March and Simon’s model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 15-28. McFarlin, D. B., & Sweeney, P. D. (1992). Distributive and procedural justice predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 626-637. McGovern, P., Hope-Hailey, V., & Stiles, P. (1998). The managerial career after downsizing: Case studies from the “leading edge.” Work, Employment, and Society, 12, 457-477. Mone, M. (1994). Relationships between self-concepts, aspirations, emotional responses, and intent to leave a downsizing organization. Human Resource Management, 33, 281-298. Morrison, E. W., & Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review, 22, 226-256. Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-organization linkages. New York: Academic Press. Noer, D. (1993). Healing the wounds. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. O’Reilly, C., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 492-499. Pearlin, L., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19, 2-21. Rousseau, D. M., & Tijoriwala, S. A. (1998). Assessing psychological contracts: Issues, alternatives, and measures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 679-695. Rudolph, B. (1998). Disconnected: How six people from AT&T discovered the new meaning of work in a downsized corporate America. New York: Free Press. Sadri, G. (1996). Reflections: The impact of downsizing on survivors—some findings and recommendations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 11, 56-59. Schellenberg, K. (1996). Taking it or leaving it: Instability and turnover in a high-tech firm. Work and Occupations, 23, 190-213. Shaw, J. B., & Barret-Power, E. (1997). A conceptual framework for assessing organization, work group, and individual effectiveness during and after downsizing. Human Relations, 50, 109-127. Smith, P. C., Balzer, W. K., Ironson, G. H., Karen, P. B., Hayes, B., Moore-Hirschl, S., & Parra, L. F. (1992). The development and validation of the stress in general (SIG) scale. Paper presented at the seventh meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Montreal, Canada. Tombaugh, J. R., & White, L. P. (1990, Summer). Downsizing: An empirical assessment of survivors’perceptions in a postlayoff environment. Organization Development Journal, pp. 32-43. Vahtera, J., Kivimaki, M., & Pentti, J. (1997). Effect of organizational downsizing on health of employees. The Lancet, 350, 1124-1128. Walsh, J. P., & Tseng, S. (1998). The effects of job characteristics on active effort at work. Work and Occupations, 25, 74-96. Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T., & Roos, D. (1990). The machine that changed the world. New York: HarperPerennial. Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com at GEORGIA TECH LIBRARY on November 13, 2014