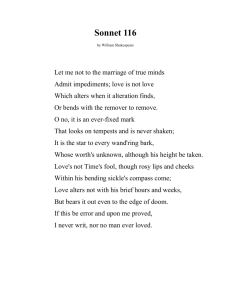

Shakespeare's Sonnets Amanova D. Shakespeare's Sonnets Shakespeare’s Sonnets are often breath-taking, sometimes disturbing and sometimes puzzling and elusive in their meanings. As sonnets, their main concern is ‘love’, but they also reflect upon time, change, aging, lust, absence, infidelity and the problematic gap between ideal and reality when it comes to the person you love. Even after 400 years, ‘what are Shakespeare’s sonnets about?’ and ‘how are we to read them?’ are still central and unresolved questions. The ‘Fair Youth’ sonnets Sonnets 1 to 126 seem to be addressed to a young man, socially superior to the speaker. The first 17 sonnets encourage this youth to marry and father children, because otherwise ‘[t]hy end is truth’s and beauty’s doom and date’ (Sonnet 14) – that is, his beauty will die with him. After this, the sonnets diversify in their subjects. Some erotically celebrate the ‘master mistress of my passion’ (Sonnet 20), while others reflect upon the ‘lovely boy’ (Sonnet 126) as a cause of anguish, as the speaker desperately wishes for his behaviour to be different to the cruelty that it sometimes is. ‘For if you were by my unkindness shaken, / As I by yours’, laments the speaker of Sonnet 120, ‘you have passed a hell of time’. The ‘Dark Lady’ sonnets Sonnets 127 to 152 seem to be addressed to a woman, the so-called ‘Dark Lady’ of Shakespearean legend. This woman is elusive, often tyrannous, and causes the speaker great pain and shame. Many of these sonnets reflect on the paradox of the ‘fair’ lady’s ‘dark’ complexion. As Sonnet 127 punningly puts it, ‘black was not counted fair’ in Shakespeare’s era, which favoured fair hair and light complexions. This woman’s eyes and hair are ‘raven black’ – and yet the speaker finds her most alluring. The two final sonnets (Sonnets 153 and 154) focus on the classical god Cupid, and playfully detail desire and longing. They do not seem to directly relate to the rest of the collection. When were Shakespeare’s Sonnets composed and published? The sonnets were probably written, and perhaps revised, between the early 1590s and about 1605. Versions of Sonnets 128 and 144 were printed in the poetry collection The Passionate Pilgrim in 1599. They were first printed as a sequence in 1609, with a mysterious dedication to ‘Mr. W.H.’ The dedication has led to intense speculation: who is ‘W.H.’? Is he the young man of the sonnets? As with the ‘Dark Lady’, various candidates have been proposed, such as William Herbert, third Earl of Pembroke, and Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. No conclusive identification has been made, and it may never be, because it is not clear that the sonnets are even about particular historical individuals. Moreover, since this dedication is by the printer, not Shakespeare, and we don’t know if Shakespeare was involved in the 1609 printing of his Sonnets, it may have no relationship to the series of feelings, relationships and anguishes that the poems map out. Shakespearean sonnets Shakespeare’s sonnets are composed of 14 lines, and most are divided into three quatrains and a final, concluding couplet, rhyming abab cdcd efef gg. This sonnet form and rhyme scheme is known as the ‘English’ sonnet. It first appeared in the poetry of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516/17– 1547), who translated Italian sonnets into English as well as composing his own. Many later Renaissance English writers used this sonnet form, and Shakespeare did so particularly inventively. His sonnets vary its configurations and effects repeatedly. Shakespearean sonnets use the alternate rhymes of each quatrain to create powerful oppositions between different lines and different sections, or to develop a sense of progression across the poem. The final couplet can either provide a decisive, epigrammatic conclusion to the narrative or argument of the rest of the sonnet, or subvert it. Sonnet 130, for example, builds up a paradoxical picture of the speaker’s mistress as defective in all the conventional standards of beauty, but the final couplet remarks that, though all this is true, And yet by heaven I think my love as rare, As any she belied with false compare.