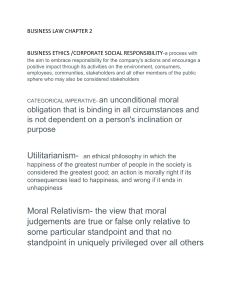

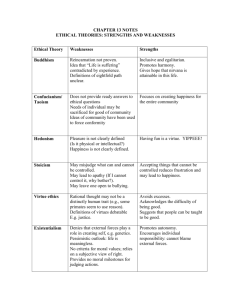

Introduction (Note: Non-relevant text has been removed from this page.) From: E. Soifer, ed., Ethical Issues: Perspectives for Canadians, 3rd edition. Broadview Press, 2009. There is another way in which the different issues are linked as well. This is that they are all moral issues. (Note: many people distinguish between “moral” and “ethical,” and the distinction is drawn in a variety of different ways. For the pur-poses of this book, however, I see no need to draw such a distinction, and so these words will be used interchangeably.) “Moral” is another word notori-ously difficult to define. I will take it that calling an issue a “moral” issue implies that it has something to do with how people should act; with what is right or wrong, or what states of affairs are good or bad. In this broad sense, it seems everyone has some moral beliefs—people who say they “don’t believe in morality” usually mean that they do not accept the particular moral “rules” dominant in their societies at the time, not that they have no beliefs what soever about what sorts of things people should or should not do. It is not necessary, of course, for individuals to have a fully worked out moral system, or a firmly established set of moral rules. People can function perfectly well with only a vague set of moral be-liefs or intuitions. Nevertheless, philosophers have often tried to provide some sort of systematic account of morality. There is considerable debate within philosophy about whether it is even possible to develop such a “moral theory,” and I do not want to pre-judge that issue here. Nevertheless, I believe it to be useful for any reader interested in these issues to have some sort of background un-derstanding of how the issues might be described in terms of various moral theories. (For one thing, x Ethical Issues Introduction writers on these issues often refer to these theories, assuming a background knowledge. For example, writers on pornography might refer to a “utilitarian” consideration of the consequences of its publication, without explaining the moral theory this word describes.) Accordingly, this book begins with an introduction to some of the most influential strands of moral theory. I leave it to the reader to decide how these might apply to the issues at hand. Utilitarianism Perhaps the single most influential moral theory over the past couple of centuries has been one called “utilitarianism.” One of its best known advocates, John Stuart Mill, described utilitarians in the 1860s as people who believe that “actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness; wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.”1 The basic intuition here seems to be that, if anything matters, happiness does, and it makes sense to try to get as much as possible of what matters. There are other theories that tell us to aim at the maximum possible amount of some other thing held to have value, such as beauty, knowledge, etc. Any such theories are commonly called “consequentialist,” because they claim that the rightness of an act depends on its having the right sort of consequences. Utilitarianism, then, is a particular form of consequentialist theory, which states that the value to be maximized is happiness (or “utility”). Utilitarianism adds to this an emphasis on equality—the belief that each entity capable of happiness is entitled to having that happiness counted equally with all others. Of course one might not get what one wants, if more people want something else, or indeed if only a few people want something else, but they want it very much. Still, nobody’s well-being is simply to be ignored. Therefore, according to utilitarianism, the way to decide which action to pursue is to add up the increase in happiness for each individual affected by the action (subtracting all unhappiness, if there is any) for each possible action, and do whichever action will produce the most happiness. Before getting into more detail about utilitarianism, it is worth mentioning another theory which is also concerned with bringing about happiness and which is commonly called “ethical egoism.” According to this view, the right thing for individuals to do is to aim at their own happiness, whether or not that coincides with the happiness of others. This view should be separated from a view known as “psychological egoism,” which holds that, as a matter of fact, human beings always do try to act in their own interests. Psychological egoism makes an empirical claim about human nature and how people do act (although it is sometimes hard to see what evidence could possibly be taken to disprove the claim, which casts doubt on its credentials as an empirical claim at all). Ethical egoism, on the other hand, makes a claim about how people should act, and indeed it might seem ethical egoism depends on the falsity of psychological egoism, since it makes little sense to say one should act in a particular way if it is in fact impossible to act in any other way. Some people would deny that ethical ego­ism is a “moral” theory at all, maintaining that morality requires people to be self-sacrificing, at least sometimes. (Egoism does recommend that people sacrifice their current interests for their long-term interests, e.g., by forcing oneself to study for an exam so as to further one’s career, even when one is more inclined to watch a movie on TV. But that might not be considered self-sacrificing.) In any case, insofar as egoism tries to provide a guide for how people should live, it deserves some mention when discussing morality. One argument often put forward for ethical egoism is that, if people pursue their own interests, everyone will be better off. This could be because each person knows his or her own interests best, and so will be in the best position to achieve them, or because such an approach would avoid the ill effects of people’s “butting in” and generally interfering with others’ business. It has also been suggested along these lines that charity is always Ethical Issues xi Introduction demeaning to the recipient, and that only ethical egoism can avoid some such element of charity. Of course, all of these are empirical claims, which might turn out to be false. For example, there could be cases where people are not the best judges of what is in their best interests, or it may be that such an egoist approach might turn out to be in the interests of some at the expense of others, rather than being better for everyone. But the main thing to note here is that these arguments are not really arguments for egoism at all, so much as arguments for a particular view of utilitarianism. The expressed goal here is “everyone’s happiness,” or “maximum happiness,” not just one’s own good. It is simply that having each pursue his or her own good is held to be the best means for bringing about the utilitarian goal. There may be other arguments which really are for ethical egoism directly, but for now I will return to utilitarianism. There is an obvious appeal to a theory that tells us to aim at maximum happiness, but there are problems as well. This is not the place to recite all of the arguments for and against this theory, but I will touch on some of the most important aspects of the ongoing debate. The first point to be noted is that, in order to use this theory, we have to have a pretty good idea of what sorts of things contribute to a person’s happiness. Although everyone has at least some rough idea about this, there are certainly cases where people might disagree; for instance, about whether a particular action has made a given individual “better off” or not. Utilitarians generally try to explain what is meant by “happiness” either in terms of some pleasant mental state, or in terms of having one’s desires satisfied. (Note that there may be cases in which these accounts have to separate, such as times when satisfaction of one’s desires does not produce the mental state one expected.) Some people, however, might claim that people can be better off in one condition than another, whether they realize it or not. For example, someone might think a person is better off doing something active with one’s leisure time, rather xii than sitting around watching television. Calling this sort of being better off a state of “happiness” might involve stretching the term a bit, but nevertheless there have been “utilitarians” who have claimed that happiness along these lines is what is to be maximized. Another problem utilitarianism faces is in deciding how to compare one person’s happiness with another’s. To take a simple case: if two children each want the last candy, how can one decide which one to give it to? Utilitarianism seems to say we should give it to the one who will enjoy it more, but it may be very hard to tell which one that is. When it comes to making decisions for large numbers of people, the problem is even greater. If a town has to decide whether to build a theatre or a gymnasium, each of which would be used by different people, how can we compare the amounts of happiness involved in either decision? These problems are compounded by the fact that we cannot foresee all the consequences of our actions, and so can’t even tell exactly how many people will be affected in the long run. These are certainly problems utilitarians should consider, but they may not be strong enough to destroy the theory. Perhaps utilitarians can claim that all we need for guiding our decisions are rough estimates. After all, nobody claims that human beings will always succeed in doing the right moral thing all the time. Perhaps trying to bring about the most happiness is all we can demand. And it seems clear that people often do use such considerations in trying to make decisions. For example, if several people want to go out to dinner together and are trying to decide where to go, it seems likely they will use elements of utilitarian reasoning. If some people like Chinese food and others prefer Italian, for example, often the decision will be made by some sort of estimate of which choice will maximize the overall happiness. Even if utilitarianism is able to deal with these problems, however, it is still not off the hook. One of the most persistent criticisms of utilitarianism has been that it fails to give the required promi- Ethical Issues Introduction nence to considerations of justice. Utilitarianism says that utility is to be maximized overall, but what if the way to achieve that is to sacrifice some individual (or group of individuals) so that others may enjoy greater benefits? Is it all right to do so, or do the individuals involved have rights that they not be treated in certain ways? A classic example of the sort of question at issue here goes as follows: suppose you are a law officer, and you are holding a person in custody. There is a mob outside threatening to riot unless you turn this person over to them, in which case the person will be abused and ultimately killed. You know that this person has done no wrong, and the mob would therefore be killing an innocent person. On the other hand, you know that if you do not turn the person over, there will be no way to prevent the mob from rioting (assume it is too late for any rational persuasion). If they do riot, there is a very good chance not only of a great deal of damage to property in the neighbourhood, but also that more innocent people (say, local residents) will be killed in the chaos. Assuming that each person’s life would contain equal happiness, it seems that the way to maximize utility would be by turning over this individual, thereby stopping the riot and saving the lives of some innocent residents. Yet many people believe that the person in custody has a right not to be treated in this way, and that one is not allowed to sacrifice this one person for the overall good. What should one do in such a case? Cases such as the one involving the innocent person in custody are often used as criticisms of utilitarianism. The claim is that the only way to maximize happiness overall is by doing something which we are not morally allowed to do. Since utilitarianism tells us to maximize happiness overall, it tells us to do something we are not morally allowed to do. No theory which sometimes tells us to do what is wrong can be the ultimate test of what is right. Utilitarians can respond to such a challenge in several ways. One way is to accept that the theory would tell us to perform actions which would be commonly considered wrong, but claim that they in fact are not wrong in the rare circumstances in which the theory says to do them. Indeed, it might be asked how we can know with certainty that certain actions (such as sacrificing an innocent person) are always wrong. How reliable are our intuitions? A second sort of response a utilitarian might offer is to deny that the proposed “wrong” action really would have the best consequences. It might be claimed, for example, that the situation as described fails to take into account long-term consequences, such as loss of trust in the law, or the guilt members of the angry mob would feel when the truth came out at a later time. Perhaps killing the innocent person appears to maximize happiness only when one fails to look at the big picture. One final sort of response utilitarians might use would be to argue that there are adequate resources within the theory to prohibit it from requiring any grossly wrong actions. One version of utilitarianism which has been claimed to have such resources is some­­times known as “indirect utilitarianism,” the best-known version of which is called “rule util­i­tar­ian­ism.”2 (The account of utilitarianism discussed above might then be called “direct” or “act” utilitarianism, for contrast.) The rule utilitarian believes that one should figure out which rules, if generally followed, would bring about the most happiness. When faced with a particular decision, this view then states that one should simply follow the rule which applies to the situation in which one finds oneself. For instance, it seems likely that a rule saying “do not kill,” if followed, would have good consequences overall, and thus it is one it seems a rule utilitarian would be likely to endorse. In the sort of “innocent person” case above, then, the rule utilitarian might simply note that that rule applies, and accordingly decide not to kill the innocent person, without needing to calculate the consequences in this particular case. This might be thought particularly valuable because people are not likely to be able to evaluate consequences accurately in the heat of the moment when action is called for. Ethical Issues xiii Introduction Act utilitarians have two main reasons for resisting rule utilitarianism. The first is that one may be virtually certain that following the generally good rule would not have the best consequences in some situations in which one finds oneself. Should one stick to the rule anyway in such a situation? What would be the justification for doing so? Since the purpose of the rule was to bring about the best consequences, it might seem odd to follow it even in cases in which it is not likely to fulfill its purpose. Indeed, philosopher J.J.C. Smart has claimed that adhering to rules in such situations amounts to “rule-worship,” and should be dismissed as irrational.3 Thus the act utilitarian claims that rules may be useful as general guidelines, but following a rule can never be an adequate substitute for calculating consequences. The second, related, objection act utilitarians raise against rule utilitarianism has to do with the specificity of the rules the rule utilitarian advocates. The rule “do not kill” does seem, at first glance, likely to maximize happiness overall, but careful thought reveals a number of possible exceptions. Perhaps the rule should be “do not kill, except in self-defense,” or “except when killing an enemy soldier while fighting a just war,” and so on. If there are too many exceptions, the rule might prove unmanageable for everyday use, and yet there might seem to be compelling reasons to allow such exceptions. Ultimately, the act utilitarian might claim that the rule would have to become something like “do not kill, except when utility would be maximized by doing so,” but that is not really anything different from what an act utilitarian would say. In other words, it could be claimed that rule utilitarianism “collapses” back into act utilitarianism. Both act and rule utilitarians believe that the ultimate moral standard lies in good consequences, specifically maximizing happiness. Theories which maintain that there are some moral considerations which do not depend on the consequences of our actions are sometimes called “deonto­logical” theories. xiv Deontological Theories Deontological theories do not have to say consequences are always unimportant, but they do have to say that the rightness of an action at least sometimes depends on qualities of the action itself, rather than its consequences. A deontologist might claim, for example, that it is always wrong to tell a lie, even if that lie will not harm anyone. Deontological theories often begin with either rights or duties. In recent political debate, it has become popular to try to draw support for one’s cause by describing it in terms of rights. Thus, people make claims ranging from “a right to treatment as an equal” and a “right to life,” through “animal rights” and “rights to national self-­determination,” to “rights to a university education” and “rights to holidays with pay.” Often, people on each side of an issue claim rights which seem to conflict with those claimed by the other side. In philosophy, some care must be taken in introducing a rights claim. It may be that some moral claims cannot properly be put in terms of rights. What sorts of entities can have rights? Must right-holders be individuals, or can there be collective rights? What is the relationship between interests and rights? Must rights be the sort of things one can choose whether or not to exercise, such as the right to free expression? Can there be “special” rights which belong to some people and not others (for example, rights police officers must have, but others should not)? And what happens when rights claims conflict? It has been suggested that rights claims should be understood in terms of several elements. One way to do this is in terms of a formula such as the following: “X has a right to Y against Z in virtue of V.” In these terms, if people make rights claims, it is permissible to press them to explain exactly what is to be substituted for each of the letters in the formula. Who has the right (X)? How did they qualify for it (V)? What is it a right to (Y)? And what does its existence imply by way of duties for others (Z)? With regard to the last of these questions, it is also possible to ask whether others Ethical Issues Introduction have a “positive” duty to provide something for the right-holder (e.g., health care), or merely a “negative” duty not to interfere (e.g., with one’s right to express oneself ). Raising these questions will often make rights claims less obvious than they may have seemed at first. The other common forms of deonto­logical theories take “duties” as the central notion of morality. Certainly much of our common moral discourse can be described in terms of duties. For example, one might assert we have a duty to refrain from murdering, or a duty not to make promises we do not intend to keep. It is possible, though, that some aspects of morality are more difficult to describe in this way. For example, if we see someone trapped in a burning building, do we have a duty to try to rescue him or her, even at the risk of our own lives, or is that something which it would be nice to do, but which is “beyond the call of duty”? Even if there is a way to describe all of our moral beliefs in terms of duties, however, there is still a problem. How do we come to know which duties we have? Where do they come from? This problem becomes more acute when we discover that different duties conflict with each other, and that people (both in different cultures and within a single one) disagree about which duties they have. For example, if I have promised to keep a secret, but it turns out someone I care about will be harmed if I do, I may be unsure about what to do. It may seem that in these sorts of cases I have two conflicting duties, and I need some way of knowing which one should give way. Similarly, at the inter-personal level, people might disagree about whether there is a duty to abstain from premarital sex, for example. How are we to decide which is right in such cases? Intuitionism Some deontological theorists have claimed that we have a faculty called “intuition” which informs us about our duties. This faculty is often seen as being similar to our senses. Just as sight can per- ceive colour and hearing can perceive sound, so intuition might be said to perceive moral facts. One problem many people have with this view is that there may not be any moral “facts” out there waiting to be perceived. The most common objection, however, is that talk of this faculty does not really explain how different people can have such different moral beliefs, nor indeed how it can come to be that whole cultures can agree within themselves, but disagree with other cultures. The intuitionist can reply that some people are simply better than others at using this faculty, just as some people may have better vision or hearing than others. Perhaps also the faculty needs to be “trained” by proper upbringing. Such a reply raises questions, however, about how we can tell which people are using the faculty “correctly” and which are not. Furthermore, a person who is uncertain how to act is not given much useful guidance if told simply to follow his or her intuition. For these sorts of reasons, many people do not find this intuitionist approach satisfactory. Kantian Ethics How else might we learn which duties we have? Perhaps the most influential deontological theorist of all has been eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant, who believed that we could discover our moral duties through the use of reason alone. He suggested that any time we are contemplating an action we should apply a rational test to it, and if it fails the test, it is an action we are not allowed to perform. This test, known as the “categorical imperative,” has a few different formulations. The best known of these are, first, that we should act as if the principle we were acting on were to become a universal law,4 and, second, that we must “treat human­ity ... always at the same time as an end and never simply as a means.”5 There has been a great deal of debate about how these principles are to be interpreted. One way to understand the first one might be by considering the question often raised when someone does a thing of which we do not Ethical Issues xv Introduction approve, which is “What if everyone did that?” (or, perhaps, “How would you like it if people did that to you?”). The second one might be understood as a requirement that we treat people with respect and concern for their integrity as people. Few would deny that these are good general guidelines for action, but many would question whether they give a full account of morality, or whether they are indeed given by reason alone. For example, one might ask what it means to treat a person as an end and not simply as a means. Does that mean we should consider each person’s well-being before we act? But that is exactly what a utilitarian would say, and Kant’s deontological approach was supposed to solve some of the problems utilitarianism runs into. And as for the “univer­salizing” version of the test, does it matter how we describe the circumstances? If we describe a given action as an act of lying, then it would seem we could not want that universalized. But if we describe it as an act of lying to a would-be murderer so as to save the life of a friend, we might come to a very different conclusion. It is not clear whether a rational test such as the categorical imperative can provide us with all the moral guidance we might want. Kant’s principles have unquestionably inspired many moral philosophers, but there is still no consensus as to how successfully he addressed the pressing ethical questions. It is also not clear whether there is another way to discover which duties apply, such as through a faculty of intuition. These deontological approaches raise some promising ideas, but cannot be said to have provided unquestionable solutions to the problems of moral philosophy. Virtue Ethics As we have seen, utilitarianism and deon­tol­­ogy each has its appeal, but each has problems as well. Many philosophers continue to believe that one of these approaches is the best one to take, and the debate rages on. Others, however, have decided that some alternative must be found. xvi One such alternative which has been around for centuries but which has become increasingly popular in recent years is what is often known as “virtue ethics.” This approach focuses on the state of character of a morally good person, rather than on a state of affairs (as utilitarianism seems to do) or on particular actions (as deontology seems to do). According to this view, the primary usage of moral terminology should be to evaluate individuals’ characters as “good” or “bad,” where a “good” person is one who chooses actions because they are of the right moral kind. Such a person acts out of a disposition to do what is morally right, rather than by weighing the alternatives of what one could do and applying a general principle to decide between them. One way of conceptualizing the difference between virtue ethics and the other types of ethical views discussed here is in terms of the central questions asked. Whereas the other views seem to focus on the question of what one should do, virtue ethics focuses on the question of what sort of person one should be. This might be thought to have the advantage of putting moral actions within the context of entire lives, rather than seeing ethical life as a series of unconnected actions. This in turn might make sense of a number of types of moral judgements we actually make. Clearly, we often do make judgements about people’s ethical character (e.g., “she’s dishonest,” or “he’s weak-willed”). What’s more, these judgements can be made even if there are some actions by the person which do not fit with the characterization. For example, a generous person may sometimes act selfishly, and still be considered a generous person. We might say the selfish action is “out of character” for that person. Another element of our moral judgements which relates to character is the element of integrity. People differ from each other in terms of their individual projects and commitments and their personal relationships. The sorts of ethical views discussed above seemed to require the same action from anyone placed in the same circumstances. Perhaps morality should not be seen Ethical Issues Introduction as “agent-neutral” in this sense, however. Perhaps one’s obligations depend upon facts about who one is, as an individual. It might make a difference, for example, whether one is the parent of one of the people affected by an action, or whe­ther one is a committed pacifist, or whether one has devoted hours to studying a particular type of architecture. To demand that everyone be required to act the same way in order to be moral might be to require people to act in ways which conflict with their deeply held convictions. Such a demand might be seen, however, to conflict with the integrity of the individual, and thus to miss a major aspect of our moral experience. One specific ethical outlook which might be considered a kind of virtue ethics is the “Ethic of Care” approach, which deserves special mention. This approach is ­often associated with feminism, and suggested differences between women and men (either biologically based or as a result of socialization). In particular, it has been claimed that women tend to think about moral situations largely in terms of caring responses to individuals involved, whereas men are more likely to try to apply general abstract principles. It has been further stated that traditional consequentialist and deontological theories have not sufficiently appreciated the value of emotional caring responses (thereby excluding women’s experience from discussion of morality). It has also been suggested that respond­ing sympathetically to the needs and desires of others might lead to a less confrontational approach to ethics, and a greater possibility of finding mutually acceptable solutions to moral problems. This approach may also be thought to have the advantage, common to virtue ethics approaches, of allowing the flexibility needed to deal with the fact that no two situations are alike. The most common objection to virtue ethics is that it is too vague to be of much use in moral decision-making. For one thing, there is a problem of knowing which character traits should be seen as “virtues,” especially in view of differences between cultures in terms of which character traits have been considered virtuous. Both utilitarians and deontologists would claim that we can decide which character traits to encourage as “virtues” only because we already know what sorts of actions we believe to be right, and then can decide which personal characteristics are most likely to lead one to perform the right actions. Even if we knew which traits were virtues, however, it might be difficult to use this information to help decide how to act in the face of moral dilemmas. If honesty and avoiding harm to others are both virtues, for example, how is one to decide whether to tell the truth when one knows doing so will cause harm? The ethical issues discussed in this book give rise to a large number of cases in which there appears to be a conflict between virtues. Deontologists and consequentialists could agree that we do evaluate people in terms of having or not having various good characteristics, but insist that we do so only because those people generally do the right sort of actions, or bring about the right sort of consequences. The fact that we do make evaluations of these various types does not by itself establish anything about which of them is most fundamental. Ethical Relativism When faced with the various difficulties which confront the leading moral theories, some philosophers have suggested that there are no universal moral truths at all—that what is “right” in a given society is whatever people in that society believe is right. This view is often called “relativism,” or, to distinguish it from other theories which sometimes go by this name, it could be called “cultural ethical relativism.” In order to assess this relativist claim, it may be useful to distinguish several different issues. First of all, it should be noted that relativists say more than that there are different beliefs in different cultures. They also make the claim that what each of these cultures believes to be right is right. One could believe the first without believing the second, however—one might think that one culture has it right while another has it wrong. Ethical Issues xvii Introduction It may be very difficult to prove that one is right and the other wrong, but that does not necessarily mean that it is not true to say it. For example, people might have different theories about why the dinosaurs died out, only one of which could be true, even if it were never possible to prove which one is correct. On the other hand, even if one is convinced that a particular culture has a mistaken moral belief, that does not automatically tell us anything about what we are allowed to do to try to change the situation. Certainly much harm has been done over the years by people who felt certain about their own moral beliefs and tried to impose these beliefs on others. Mistakes of that sort have no doubt helped convince many people that a relativist approach is the only one we can adopt, practically speaking. However, one might think that tolerance of others’ difference is a very important moral value all by itself, and therefore one might disapprove of such impositions of moral belief, even while believing that one particular set of beliefs is morally best in some objective sense. Indeed, many people’s common-sense moral beliefs seem to reflect such a value, but also place a limitation upon it. If, for example, the dominant view in another culture is that women should not be treated as equals, or that slavery or torture is acceptable, many people might think we have an obligation to try to convince that culture of the error of its ways. We may or may not be entitled to use force to bring about the change, but many would say we should do more than simply say “Well, that’s their business” and stay out of the picture. Indeed, if relativism is correct, it becomes hard to see how people can engage in ethical debate even within a single culture. One might wonder how we are to ­determine what a culture believes (Does everyone with­in the culture have to believe it? Nearly everyone? Just over half the people?). Once one has settled that, however, it seems one needs merely to take a vote in order to discover whether something is morally acceptable. Consider as an example the issue of capital punishment. If most people think capital punishment is xviii acceptable, and I do not think so, it seems there is nothing I could say to convince them. The simple fact that they think it is unacceptable would be enough to settle the issue, if the test of moral rightness is what people believe to be right. It should also be noted that the same sort of reasoning which supports cultural ethical relativism might be taken to support what we might call “individual ethical relativism,” the claim that what each individual thinks is right is right for that individual. Note, however, that accepting this would make it virtually impossible to justify any sort of moral criticism of others (and might also make it difficult to explain what it is one does if one changes one’s mind about an ethical matter). One other problem which cultural ethical relativists must face is in explaining how to identify a culture. Many countries (including Canada) are made up of several different cultural groups. Whether one refers to them as “cultures” or “subcultures” or by some other name, the problem remains that it is difficult to make any strong claims about what the present culture of Canada believes. (Note: some issues relating to this observation are among those discussed in Part 7, on multiculturalism, nationalism, and aboriginal rights.) Nevertheless, presumably issues such as those raised in this book must be approached from within some sort of cultural framework, and some of the questions (such as what laws, if any, there should be governing such things as abortion, treatment of the environment, and distribution of pornography) seem to require answers which can be applied to all Canadians. I have suggested that cultural ethical relativism has problems, but it is still possible that these problems could be overcome, and convincing reasons put forward for accepting cultural ethical relativism. To that extent, relativism is still a live issue. Perhaps it is best to approach the ethical issues discussed in this book with the aim of discovering answers which apply here and now, and postpone the question of whether these answers can be universally applicable. Clearly relativism does raise interesting questions about the very Ethical Issues Introduction nature of moral reasoning, but one should not conclude from the fact that people disagree about an issue that there is no possibility of establishing that one view about it is better than others. Application As we have seen, there is a great deal of question about which moral theory is the best, or even about whether we should aim for moral theories at all. Much interesting work is being done in this area, and it is well worth investigating further, but this is not the place to do so. Instead, I will now turn to the question of how moral theories might apply to specific moral issues. The classic view has been that one should work out the best moral theory, and then apply it to specific issues (hence the common term “applied ethics” for discussion of such contemporary moral issues). According to this view, one might decide, for example, that utilitarianism is the best view available, and then simply resolve the issues by trying to determine which action or policy would maximize happiness. Alternatively, one might test various policies to see if they conform to the categorical imperative, and so on. Not everyone would accept this approach, however. Some argue that we can be much more certain of our beliefs about these concrete cases than we can about rather abstract moral theories. Others point out that in the heat of the moment, we often do not have time to calculate what our chosen moral theory dictates, and so must simply apply, as well as we can, general common-sense rules which we have adopted earlier. I do not propose to settle these issues here. One could write a whole book on whether moral issues are best dealt with by applying moral theories—but that would be a different book. The information in this introduction is meant to familiarize the reader with some of the terms which may be referred to in the pieces which follow, and to provide some introductory background information about the nature of moral philosophy. What you make of that information, and of the arguments and ideas which follow, is up to you. Notes 1 J.S. Mill, Utilitarianism, originally published 1861, Hackett edition (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1979), p. 7. 2 Another version of indirect utilitarianism, which might be called “disposition utilitarianism,” might tell a person to foster whichever dispositions are most likely to maximize happiness overall, and then simply act in accordance with one’s dispositions in various situations. 3 J.J.C. Smart, “Extreme and Restricted Utilitarianism,” as printed in P. Foot (ed.), Theories of Ethics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967), pp. 176–77. 4 I. Kant, Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals, (J.W. Ellington, trans.), (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1981), p. 30, or p. 421 in the standard pagination. 5 Ibid., p. 36, or p. 429 in the standard pagination. Ethical Issues xix