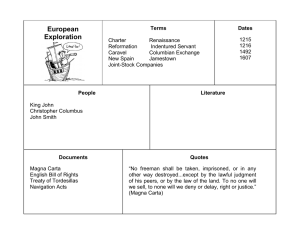

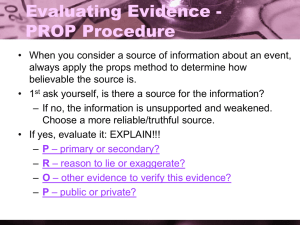

The Optimist’s Guide To The AI Governance Challenge How interactions between humans and machines can shape a brighter future TA B L E O F C O N T E N T S 2 Editor’s Note 4 A Magna Carta for Inclusivity and Fairness in the Global AI Economy 12 Humans and AI: Rivals or Romance? 18 Why Machines Will Not Replace Us 24 The AI Governance of AI 31 AI and the Future of Lie Detection 37 Conclusion 1 Editor’s Note Relevance of TITLE On OFthe THIS CHAPTER Behavioral Science to AI SHALL GO HERE 2 On the Relevance of Behavioral Science to AI Even as we continue to develop a fuller understanding of the mechanisms that underlay human judgment and decision-making, advancements in intelligent machinery are forcing us to codify the processes by which decisions are, and should be, made. Should your self-driving Uber be allowed to break traffic regulations in order to safely merge onto the highway? To what extent are algorithms as prone to discriminatory patterns of thinking as humans – and how might a regulatory body make this determination? More fundamentally, as more tasks are delegated to intelligent machines, to what extent will those of us who are not directly involved in the development of these technologies be able to influence these critical decisions? It is with these questions in mind that we are pleased to have adapted the following series of articles for publication at TDL. – Andrew Lewis, Editor-in-Chief 3 Chapter One A Magna ta for TITLE OF THIS Car CHAPTER Inclusivit y and Fairness in SHALL GO HERE the Global AI Economy 4 A Magna Carta for Inclusivity and Fairness in the Global AI Economy by Olaf Groth, Mark Nitzberg and Mark Esposito We stand at a watershed moment for society’s vast, unknown digital future. A powerful technology, artificial intelligence (AI), has emerged from its own ashes, thanks largely to advances in neural networks modeled loosely on the human brain. AI can find patterns in massive unstructured data sets and improve its own performance as more data becomes available. It can identify objects quickly and accurately, and make ever more and better recommendations — improving decision-making, while minimizing interference from complicated, political humans. This raises major questions about the degree of human choice and inclusion for the decades to come. How will humans, across all levels of power and income, be engaged and represented? How will we govern this brave new world of machine meritocracy? 5 Machine meritocracy To find perspective on this questions, we must travel back 800 years: It was January, 1215, and King John of England, having just returned from France, faced angry barons who wished to end his unpopular vis et voluntas (“force and will”) rule over the realm. In an effort to appease them, the king and the Archbishop of Canterbury brought 25 rebellious barons together to negotiate a “Charter of Liberties” that would enshrine a body of rights to serve as a check on the king’s discretionary power. By June they had an agreement that provided greater transparency and representation in royal decision-making, limits on taxes and feudal payments, and even some rights for serfs. The famous “Magna Carta” was an imperfect document, teeming with special-interest provisions, but today we tend to regard the Carta as a watershed moment in humanity’s advancement toward an equitable relationship between power and those subject to it. It set the stage eventually for the Enlightenment, the Renaissance, and democracy. Balance of power It is that balance between the ever-increasing power of the new potentate — the intelligent machine — and the power of human beings that is at stake. Increasingly, our world will be one in which machines create ever more value, producing more of our everyday products. As this role expands, and AI improves, human control over designs and decisions will naturally decrease. Existing work and life patterns will be forever changed. Our own creation is now running circles around us, faster than we can count the laps. 6 Machine decisions This goes well beyond jobs and economics: in every area of life machines are starting to make decisions for us without our conscious involvement. Machines recognize our past patterns and those of (allegedly) similar people across the world. We receive news that shapes our opinions, outlooks, and actions based on inclinations we’ve expressed in past actions, or that are derived from the actions of others in our bubbles. While driving our cars, we share our behavioral patterns with automakers and insurance companies so we can take advantage of navigation and increasingly autonomous vehicle technology, which in return provide us new conveniences and safer transportation. We enjoy richer, customized entertainment and video games, the makers of which know our socioeconomic profiles, our movement patterns, and our cognitive and visual preferences to determine pricing sensitivity. As we continue to opt-in to more and more conveniences, we choose to trust a machine to “get us right.” The machine will get to know us in, perhaps, more honest ways than we know ourselves — at least from a strictly rational perspective. But the machine will not readily account for cognitive disconnects between that which we purport to be and that which we actually are. Reliant on real data from our real actions, the machine constrains us to what we have been, rather than what we wish we were or what we hope to become. 7 Personal choice Will the machine eliminate that personal choice? Will it do away with life’s serendipity — planning and plotting our lives so we meet people like us, thus depriving us of encounters and friction that force us to evolve into different, perhaps better human beings? There’s tremendous potential in this: personal decisions are inherently subjective, but many could be improved by including more objective analyses. For instance, including the carbon footprint for different modes of transportation and integrating this with our schedules and pro-social proclivities may lead us to make more eco-friendly decisions; getting honest pointers on our more and less desirable characteristics, as well as providing insight into characteristics we consistently find appealing in others, may improve our partner choices; curricula for large and diverse student bodies could become more tailored to the individual, based on the engine of information about what has worked in the past for similar profiles. Polarization But might it also polarize societies by pushing us further into bubbles of like-minded people, reinforcing our beliefs and values without the random opportunity to check them, defend them, and be forced to rethink them? AI might get used for “digital social engineering” to create parallel micro-societies. Imagine digital gerrymandering with political operatives using AI to lure voters of certain profiles into certain districts years ahead of elections, or AirBnB micro-communities only renting to and from certain socio-political, economic, or psychometric profiles. Consider companies being able to hire in much more surgically-targeted fashion, at once increasing their success rates and also compromising their strategic optionality with a narrower, less multi-facetted employee pool. 8 Who makes judgments? A machine judges us on our expressed values — especially those implicit in our commercial transactions — yet overlooks other deeply held values that we have suppressed or that are dormant at any given point in our lives. An AI might not account for newly formed beliefs or changes in what we value outside the readily-codified realm. As a result, it might, for example, make decisions about our safety that compromise the wellbeing of others — doing so based on historical data of our judgments and decisions, but resulting in actions we find objectionable in the present moment. We are complex beings who regularly make value trade-offs within the context of the situation at hand, and sometimes those situations have little or no codified precedent for an AI to process. Will the machine respect our rights to free will and self-reinvention? Discrimination and bias Similarly, a machine might discriminate against people of lesser health or standing in society because its algorithms are based on pattern recognition and broad statistical averages. Uber has already faced an outcry over racial discrimination when its algorithms relied on zip codes to identify the neighborhoods where riders were most likely to originate. Will the AI favor survival of the fittest, the most liked, or the most productive? Will it make those decisions transparently? What will our recourse be? 9 Moreover, a programmer’s personal history, predisposition, and unseen biases — or the motivations and incentives of or from their employer — might unwillingly influence the design of algorithms and sourcing of data sets. Can we assume an AI will work with objectivity all the time? Will companies develop AIs that favor their customers, partners, executives, or shareholders? Will, for instance, a healthcare-AI jointly developed by technology firms, hospital corporations, and insurance companies act in the patient’s best interest, or will it prioritize a certain financial return? We can’t put the genie back in the bottle, nor should we try — the benefits will be transformative, leading us to new frontiers in human growth and development. We stand at the threshold of an evolutionary explosion unlike anything in the last millennium. And like all explosions and revolutions, it will be messy, murky, and fraught with ethical pitfalls. A new charter of rights Therefore, we propose a Magna Carta for the Global AI Economy — an inclusive, collectively developed, multistakeholder charter of rights that will guide our ongoing development of artificial intelligence and lay the groundwork for the future of human-machine co-existence and continued, more inclusive, human growth. Whether in an economic, social, or political context, we as a society must start to identify rights, responsibilities, and accountability guidelines for inclusiveness and fairness at the intersections of AI and human life. Without it, we will not establish enough trust in AI to capitalize on the amazing opportunities it can and will afford us. 10 Moreover, a programmer’s personal history, predisposition, and unseen biases — or the motivations and incentives of or from their employer — might unwillingly influence the design of algorithms and sourcing of data sets. Can we assume an AI will work with objectivity all the time? Will companies develop AIs that favor their customers, partners, executives, or shareholders? Will, for instance, a healthcare-AI jointly developed by technology firms, hospital corporations, and insurance companies act in the patient’s best interest, or will it prioritize a certain financial return? We can’t put the genie back in the bottle, nor should we try — the benefits will be transformative, leading us to new frontiers in human growth and development. We stand at the threshold of an evolutionary explosion unlike anything in the last millennium. And like all explosions and revolutions, it will be messy, murky, and fraught with ethical pitfalls. A new charter of rights Therefore, we propose a Magna Carta for the Global AI Economy — an inclusive, collectively developed, multistakeholder charter of rights that will guide our ongoing development of artificial intelligence and lay the groundwork for the future of human-machine co-existence and continued, more inclusive, human growth. Whether in an economic, social, or political context, we as a society must start to identify rights, responsibilities, and accountability guidelines for inclusiveness and fairness at the intersections of AI and human life. Without it, we will not establish enough trust in AI to capitalize on the amazing opportunities it can and will afford us. 11 Chapter Two andCHAPTER AI: Rivals TITLEHumans OF THIS or Romance? SHALL GO HERE 12 Humans and AI: Rivals or Romance? by Terence Tse, Mark Esposito and Danny Goh We stand at a watershed moment for society’s vast, unknown digital future. A powerful technology, artificial intelligence (AI), has emerged from its own ashes, thanks largely to advances in neural networks modeled loosely on the human brain. AI can find patterns in massive unstructured data sets and improve its own performance as more data becomes available. It can identify objects quickly and accurately, and make ever more and better recommendations — improving decision-making, while minimizing interference from complicated, political humans. This raises major questions about the degree of human choice and inclusion for the decades to come. How will humans, across all levels of power and income, be engaged and represented? How will we govern this brave new world of machine meritocracy? 13 The (human) empire strikes back It’s certain that we will hear more and more alarmist accounts. However, we have seen it before – many times, in fact. Back in 1963, it was J F Kennedy who said, “We have a combination of older workers who have been thrown out of work because of technology and younger people coming in […] too many people are coming into the labor market and too many machines are throwing people out” [4]. Going further back, when the first printed books with illustrations started to appear in the 1470s in Germany, wood engravers protested as they thought they would no longer be needed [5].But this all begs one question: If technological progress represents a comprehensive threat to humans, then why do we still have jobs left? In fact, many of us are still working, probably much harder than before. The answer: machines and humans excel in different activities. For instance, machines are frequently no match for our human minds, senses and dexterity. For example, even though Amazon’s warehouses are automated, humans are still required to do the actual shelving. And this doesn’t only apply to physical jobs. The real story behind today’s AI is that it cannot function without humans in the loop. Google is thought to have 10,000 ‘raters’ who look at YouTube videos or test new services. Microsoft, on the other hand, has a crowdsourcing platform called Universal Human Relevance System to handle a great deal of small activities, including checking the results of its search algorithms [6]. And this blend of AI and humans, who follow through when the AI falls short, is not going to disappear any time soon [7]. Indeed, the demand for such on-demand human interventions is expected to continue to grow. The ‘human cloud’ is set to boom. 14 Closer together The above illustrates a very important lesson – humans will be needed. The key is how to integrate humans and machines in various activities and how to steer AI towards the creation of new economic interfaces, rather than towards the mere replacement/displacement of existing ones. At the moment, the probability of AI getting things right is between 85 and 95 per cent. Humans, on the other hand, generally score 60 to 70 per cent. On this basis alone, we need only machines and not humans. Yet, in some highly data-driven industries such as financial and legal services, there can be no error – any mistake can result in huge financial costs in the form of economic losses or expensive lawsuits. Machines by themselves are not enough. Furthermore, AI can only run an algorithm that is predefined and trained by a human, and so a margin of error will always exist. When mistakes take place, AI will not be able to fix them. Humans, by contrast, are able to create solutions to problems. We believe that the best solution is to use machines to run production up to the level of 95 per cent accuracy, and supplement this with human engineers to mitigate risks if not to strive to improve accuracy. Humans and machines will – and must – work together. As business consultants, educators and policy advisors, we all strongly believe that, ultimately, what really matters is how to prepare people to work increasingly closely with machines. 15 Closer together The above illustrates a very important lesson – humans will be needed. The key is how to integrate humans and machines in various activities and how to steer AI towards the creation of new economic interfaces, rather than towards the mere replacement/displacement of existing ones. At the moment, the probability of AI getting things right is between 85 and 95 per cent. Humans, on the other hand, generally score 60 to 70 per cent. On this basis alone, we need only machines and not humans. Yet, in some highly data-driven industries such as financial and legal services, there can be no error – any mistake can result in huge financial costs in the form of economic losses or expensive lawsuits. Machines by themselves are not enough. Furthermore, AI can only run an algorithm that is predefined and trained by a human, and so a margin of error will always exist. When mistakes take place, AI will not be able to fix them. Humans, by contrast, are able to create solutions to problems. We believe that the best solution is to use machines to run production up to the level of 95 per cent accuracy, and supplement this with human engineers to mitigate risks if not to strive to improve accuracy. Humans and machines will – and must – work together. As business consultants, educators and policy advisors, we all strongly believe that, ultimately, what really matters is how to prepare people to work increasingly closely with machines. 16 References [1] Frey, Carl Benedikt and Osborne, Michael. The Future of Employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Oxford Martin School, 2013. http://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/publications/view/1314 [2] Chui, Michael, Manyika, James, and Miremadi, Mehdi. How Many of Your Daily Tasks Could Be Automated?, Harvard Business Review, 14 December 2015. (https://hbr.org/2015/12/how-many-of-your-daily-tasks-could-beautomated) [3] Tse, Terence and Esposito, Mark. Understanding How the Future Unfolds: Using Drive to Harness the Power of Today’s Megatrends. Lion Crest, 2017. [4] John F Kennedy interview by Walter Cronkite, 3 September 1963, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RsplVYbB7b8 [5] The Economist. Artificial intelligence will create new kinds of work, 26 August 2017. https://www.economist.com/news/business/21727093humans-will-supply-digital-services-complement-ai-artificial-intelligence-willcreate-new [6] Ibid. [7] Gray, Mary L. and Suri, Siddharth. “The humans working behind the AI curtain,”Harvard Business Review, 9 January 2017. 17 Chapter Three Machines Will TITLE Why OF THIS CHAPTER Not Replace Us SHALL GO HERE 18 Why Machines Will Not Replace Us by Terence Tse, Mark Esposito and Danny Goh Lately, we have received quite a number of requests asking us to explain further why artificial intelligence (AI) and robots are unlikely to put humans out of work soon. It may be a contrarian position, but we are definitely optimistic about the future, believing that the displacement of labour won’t turn out to be as gloomy as many are speculating. Despite the endless talk on the threat of machines to human jobs, the truth is that, while we have lost jobs in some areas, we have gained them in others. For instance, the invention of automatic teller machines (ATMs), introduced in the 1960s, ought to have eliminated the need for many bank employees in the US. Yet, over time, the industry has not just hired more staff, but job growth in the sector is, in fact, doing better than the average [1].So, why is this? The answer can actually be found in Hollywood movies. In the 1957 film Desk Set, the entire audience research department in a company is about to be replaced by a giant calculator. 19 It is a relief to the staff, however, when they find out that the machine makes errors, and so they get to keep their jobs, learning to work alongside the calculator. Fast forward to the 2016 film Hidden Figures. The human ‘computers’ at NASA are about to be replaced by the newly introduced IBM mainframe. The heroine, Dorothy Vaughan, decides to teach herself Fortran, a computer language, in order to stay on top of it. She ends up leading a team to ensure the technology performs according to plan. Facts and not fantasies These are not merely fantasies concocted by film studios. Granted, realistically, many jobs, especially those involving repetitive and routine actions, may succumb to automation for good. But the movies above do encourage us not to overrate computers and underrate humans. Delving deeper into this, we believe there are several elements that underpin this message. Only humans can do non-standardised tasks. While traditional assembly line workers are set to be replaced by automation, hotel housekeeping staff are unlikely to face the same prospect any time soon. Robots are good at repetitive tasks but lousy at dealing with varied and unique situations. Jobs like room service require flexibility, object recognition, physical dexterity and fine motor coordination; skills like these are – at the moment at least – beyond the capabilities of machines, even for those considered intelligent. 20 Machines make human skills more important. It is possible to imagine an activity – such as a mission or producing goods – to be made up of a series of interlocking steps, like the links in a chain. A variety of elements goes into these steps to increase the value of the activity, such as labour and capital; brain and physical power; exciting new ideas and boring repetition; technical mastery and intuitive judgement; perspiration and inspiration; adherence to rules; and the considered use of discretion. But, for the overall activity to work as expected, every one of the steps must be performed well, just as each link in a chain must do its job for the chain to be complete and useful. So, if we were to make one of these steps or links in a chain more robust and reliable, the value of improving the other links goes up [2]. In this sense, automation does not necessarily make humans superfluous. Not in any fundamental way, at least; instead, it increases the value of our skill sets. As AI and robots emerge, our expertise, problem-solving, judgement and creativity are more important than ever [3]. For example, a recent study looks into a Californian tech startup. Despite the company providing a technology-based service, it finds itself to be growing so fast that, with the computing systems getting larger and more complex, it is constantly drafting in more humans to monitor, manage and interpret the data [4]. Here, the technologies are merely making the human skills more valuable than before. 21 Social aspects matter. Perhaps one of the most telling lessons learnt from underestimating the power of human interactions can be found by looking at Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Until recently, it was widely believed that the rise of digital teaching tools would make human teachers less relevant, or even superfluous. However, that was not found to be the case with MOOCs. Instead, they have shown that human teachers can be made more effective with the use of digital tools. The rise of hybrid programmes, in which online tools are combined with a physical presence, has only partially reduced the number of face-to-face hours for teachers, while freeing them up to be more involved with curriculum design, video recording and assessment writing. Ultimately, it is this combination of human interactions and computers that champions [5].Human resistance is not futile. Many of us have witnessed seemingly promising IT projects end up in failure. But, very often, this is not the result of technological shortcomings. Instead, it is the human users that stand in the way. Unfamiliar interfaces, additional data-entry work, disruptions to routines, and the necessity to learn and understand the goals the newly implemented system is trying to achieve, for instance, often cause frustration. The aftermath is that people can put up an enormous amount of resistance to taking on novel technologies, no matter how much the new systems would benefit them and the company. Such an urge to reject new systems is unlikely to change in the short term. 22 Closer together There is simply no reason to think that AI and robots will render us redundant. It is projected that, by 2025, there will be 3.5 million manufacturing job openings in the US, and yet 2 million of them will go unfilled because there will not be enough skilled workers [6]. In conclusion, rather than undermining humans, we are much better off thinking hard about how to upskill ourselves and learn how to work alongside machines, as we will inevitably coexist – but it won’t be a case of us surrendering to them. References [1] Bessen, James. Learning by Doing: The Real Connection Between Innovation, Wages, and Wealth. Yale University Press, 2015. [2] This is called the O-ring theory or principle, which was put forward by Michael Kremer in 1993. The name comes from the disaster of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986, which was caused by the failure of a single O-ring. In this case, an inexpensive and seemingly inconsequential rubber O-ring seal in one of the booster rockets failed after hardening and cracking during the icy Florida weather on the night before the launch. [3] Autor, David. “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3-30, 2015. [4] Shestakofsky, Benjamin. “Working Algorithms: Software Automation and the Future of Work”, Work and Occupations, 44(4), 2017. [5] Tett, Gillian. “How robots are making humans indispensable”, Financial Times, December 22, 2016. https://www.ft.com/content/da95cb2c-c6ca11e6-8f29-9445cac8966f [6] Manufacturing Institute and Deloitte, Skills Gap in US Manufacturing, 2017. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/manufacturing/articles/skills-gapmanufacturing-survey-report.html 23 Chapter four Governance of TITLEThe OFAITHIS CHAPTER AI SHALL GO HERE 24 The AI Governance of AI by Josh Entsminger, Mark Esposito, Terence Tse and Danny Goh Our lives are ruled by data. Not just because it informs companies of what we want, but because it helps us to remember and differentiate what we want, what we need, and what we can ignore. All these decisions give way to patterns, and patterns, when aggregated, give us a picture of ourselves. A world where such patterns follow us, or even are sent ahead of us — to restaurants to let them know if we have allergies, to retail stores to let them know our preferred clothing size —is now so feasible that labeling it science fiction would expose a lack of awareness more than a lack of imagination. The benefits of AI are making many of our choices easier and more convenient, and in so doing, tightening competition in the space of customer choice. As this evolution happens, the question is less to what extent AI is framing our choices, but rather, how it is shaping them. In such a world, we need to understand when our behavior is being shaped, and by whom. 25 Clearly, most of us are quite comfortable living in a world where our choices are shaped by AI. Indeed, we already live in such a world: from search engines to smooth traffic flow, many of our daily conveniences are built on the speed provided by the backend. The question we need to ask ourselves when considering AI, and its governance, is whether we are comfortable living in a world where we do not know if, and how, we are being influenced. Behavioral Bias or Behavioral Cues AI can do for our understanding of behavior what the microscope did for biology. We have already reached the point where software can discover tendencies in our behavioral patterns we might not consider, identifying traits that our friends and family would not know. The infamous, but apocryphal, story of the father who discovered his daughter was pregnant when Target began sending advertisements for baby suppliers (after detecting a shift in her spending) gives us a sneak peek.[2] Our lives are already ruled by probabilistic assumptions, intended to drive behavior. Now we need to ask, and answer honestly, how much of your life are you willing to have shaped by algorithms you do not understand? More importantly, who should be tasked with monitoring these algorithms to flag when they have made a bad decision, or an intentionally manipulative one? 26 As more companies use AI, and the complexity of its insights continues to grow, we will be facing a gap above the right to an understanding, or the right to be informed – we will be facing a gap concerning when, and if, a violation has occurred at all. As our digital presence grows, and this presence is being pulled by public directions for the future of e-governance and private for how we engage with our interests – meaningful governance will have to include an essential first step, the right to know how our data is being used, who has it, and when are they using it. Another example of how behavior and technology are interfacing at a faster than ever pace is through the observation of what Chatbots have been shown to provide us: the potential for emotional associations, which might be used for manipulative purposes.[2] As developments in natural language processing grow to combine with advanced robotics, the potential of building that bond from touch, warmth, comfort, also grows – particularly in a world where we experience the largest endemic of loneliness, driving the UK to literally appoint a minister for loneliness. As machine to machine data grows in the internet of things, companies with preferential access will have more and more insight into more and more minute aspects of behavioral patterns we ourselves might not understand — and with that comes a powerful ability to nudge behavior. Good data is not just about volume, it is about veracity — as IoT grows, we are handing firms everything they need to know about us on a silver platter. 27 We can argue still that the issue is not the volume, the issue is the asymmetry of analytic competency in managing that volume — meaning asymmetries in capturing value. In turn, this means some companies not only understand you, but can predict your behaviour to the point of knowing how to influence a particular choice most effectively. In the age of big data, the best business is the insight business. Accountability: who is looking after us? The first question concerning building accountability is how to keep humans in the decision loop of processes made more autonomous through AI. The next stage needs to preserve accountability in the right to understanding — to know why an algorithm made one decision instead of another. New proposals are already emerging on how to do this — for example, when specific AI projects are proprietary aspects of a firm’s competitiveness, we might be able to use counterfactual systems to assess all possible choices faced by an AI.[3] But systems that map decisions without breaking the black box will not be able to provide the rationale by which that algorithm made one decision instead of another. 28 Yet the problem still goes deeper. The problem with transparency models is the assumption that we will even know what to look for — that we will know when there needs to be a choice in opting out of a company’s use of data. In the near future, we may not be able to understand by ourselves when an AI is influencing us. This leads us to a foundational issue: to govern AI, we may need to use AI. We will need AI not just to understand when we are being influenced in overt ways, but to understand the new emerging ways in which companies can leverage the micro-understanding of our behavior. The capacity for existing legal frameworks, existing political institutions, and existing standards of accountability to understand, predict, and catch the use of AI for manipulative purposes is sorely lacking. Algorithmic collusion is already a problem — with pricing cartels giving way to pop-up pricing issues that can disappear, without prior agreement, thus avoiding the initial claims.[4] We can imagine a world where collusion is organized not by the market, but by tracking the behavior of distinct groups of individuals to organize micro-pricing changes. Naturally, questions emerge: who will govern the AI that we use to watch AI? How will we know that collusion is not emerging between the watchers and the watched? What kind of transparency system will we need for a governing AI to minimize the transparency demands for corporate AI? 29 The future of AI governance will be decided in the margins — what we need to pay attention to is less the shifting structure of collusion and manipulation, but the conduct, and the ability for competent AI to find the minimal number of points of influence to shape decision making. We need to have a conversation to make our assumptions and beliefs about price fixing, about collusion, about manipulation, painfully clear. In an age of AI, we cannot afford to be vague. References [1] Piatetsky, Gregory. Did Target really predict a teens pregnancy? The Inside Story May 7 2014 KD nuggets [2] Yearsly, Liesl. We need to talk about the power of AI to manipulate humans. June 5 2017. MIT Tech Review [3] Mittelstadt, Brent. Wachter, Sandra. Could counterfactuals explain algorithmic decisions without opening the black box? 15 January 2018. Oxford Internet Institute Blog [4] Algorithms and Collusion: Competition Policy in the Digital Age. OECD 2017 30 Chapter five theCHAPTER Future of TITLEAIOFand THIS Lie Detection SHALL GO HERE 31 AI and the Future of Lie Detection by Josh Entsminger, Mark Esposito, Terence Tse and Danny Goh We live in a world now where we know how to lie. With advances in AI, it is very likely that we will soon live in a world where we know how to detect truth. The potential scope of this technology is vast — the question is how should we use it? Some people are naturally good liars, and others are naturally good lie detectors. For example, individuals who fit the latter description can often sense lies intuitively, observing fluctuations in pupil dilation, blushing, and a variety of micro-expressions and body movements that reveal what’s going on in someone else’s head. This is because, for the vast majority of us who are not trained deceivers, when we lie, or lie by omission, our bodies tend to give us away. For most of us, however, second guessing often overtakes intuition about whether someone is lying. Even if we are aware of the factors that may indicate a lie, we are unable to simultaneously observe and process them in real time — leaving us, ultimately, to guess whether we are hearing the truth. 32 Now suppose we did not have to be good lie detectors, because we would have data readily available to know if someone was lying or not. Suppose that, with this data, we could determine with near-certainty the veracity of someone’s claims. We live in a world now where we know how to lie. With advances in AI, it is very likely that we will soon live in a world where we know how to detect truth. The potential scope of this technology is vast — the question is how should we use it? The Future of AI Lie Detection Imagine anyone could collect more than just wearable data showing someone’s (or their own) heartbeat, but continuous data on facial expressions from video footage, too. Imagine you could use that data, with a bit of training, to analyze conversations and interactions from your daily life — replaying ones you found suspicious with a more watchful gaze. Furthermore, those around you could do the same: imagine a friend, or company, could use your past data to reliably differentiate between your truths and untruths, matters of import and things about which you could not care less. This means a whole new toolkit for investigators, for advertisers, for the cautious, for the paranoid, for vigilantes, for anyone with internet access. Each of us will have to know and understand how to manage and navigate this new data-driven public record of our responses. 33 The issue for the next years is not whether lying will be erased — of course it will not —but rather, how these new tools should be wielded in the pursuit of finding the truth. Moreover, with a variety of potential ways of mis-reading and misusing these technologies, in what contexts should they be made available, or promoted? The issue for the next years is not whether lying will be erased — of course it will not —but rather, how these new tools should be wielded in the pursuit of finding the truth. Moreover, with a variety of potential ways of mis-reading and misusing these technologies, in what contexts should they be made available, or promoted? The Truth About Knowing the Truth Movies often quip about the desire to have a window into someone else’s brain, to feel assured that what they say describes what they feel, that what they feel describes what they will do, and what they will do demonstrates what everything means for them. Of course, we all know the world is not so neat, and one might fall prey to searching for advice online. What happens when such advice is further entrenched in a wave of newly available, but poorly understood, data? 34 What will happen, for example, when this new data is used in the hiring process, with candidates weeded out by software dedicated to assessing whether and about what they’ve lied during an interview? What will happen when the same process is used for school selection, jury selection, and other varieties of interviews, or when the results are passed along to potential employers. As the number of such potential scenarios grows, the question we have to ask is when is our heartbeat private information? Is knowledge of our internal reactions itself private, simply because until now only a small segment of perceptive people could tell what was happening? Communities often organize around the paths of least resistance, creating a new divide between those who understand and can navigate this new digital record, and those who cannot. Imagine therapists actively recording cognitive dissonance, news shows identifying in real time whether or not a guest believes what they are saying, companies reframing interviews with active facial analysis, quick border security questioning. The expanding scope of sensors is pushing us away from post-truth to an age of post-lying, or rather, an end to our comfort with the ways in which we currently lie. As with everything, the benefits will not be felt equally. We might even be able to imagine the evolution of lie detection moving towards brain-computer interfaces — where one’s right to privacy must then be discussed in light of when we can consider our thoughts private. 35 In court rooms, if we can reliably tell the difference between reactions during a lie and during the truth, do witnesses have a right to keep that information private? Should all testimonials be given in absolute anonymity? Researchers at the University of Maryland developed DARE, the Deception Analysis and Reasoning Engine, which they expect to be only a few years away from near perfect deception identification. How then should we think about the 5th amendment of the US constitution, how should we approach the right to not incriminate oneself? With the advent of these technologies, perhaps the very nature of the courtroom should change. Witnesses are not given a polygraph on the stand for good reason: it’s unreliable — but there may be little stopping someone with a portable analytics system to tell their vitals or analyze a video feed from a distance, and publish the results for the court of public opinion. How should our past behavior be recorded and understood? How we design nudges, how we design public spaces, how we navigate social situations, job offers, personal relationships, all depend on a balance of social convention by which we allow ourselves — and others — to hide information. Yet, what should we do with a technology that promises to expose this hidden information? Is a world based on full-truths preferable to the one we have now? Will we have a chance to decide? Advances in AI and the democratization of data science are making the hypothetical problem of what kind of world we prefer an all too real discussion, one we need to have soon. Otherwise we’ll have no say in determining what lies ahead. 36 Closing Remarks OnOF TheTHIS Future Discourse TITLE CHAPTER Around AI & Behavior SHALL GO HERE 37 On The Future Discourse Around AI & Behavior Much of the conversation around AI has been on the impact it will have on our working lives. While this is an important issue and certainly a very visible one these days, in many ways it only scratches the surface of the true impact AI is poised to have on humanity. As AI becomes more and more commoditized and becomes a bigger part of our physical and social environment, we believe the conversation will begin to shift from critical to constructive - from 'Will AI pose a huge threat to human welfare?' to 'How can we make sure the impact of AI on welfare is as sustained and equitable as possible'. With this in mind, we believe that it is crucial to start a discourse about the intersection of AI and behavior science, in particular the behavioral economics and social psychology of human-computer interactions in a world run by algorithms. We hope that this document has been a first step in a direction toward this AI-humanism. 38 TITLE OF Authors THIS CHAPTER SHALL GO HERE 39 Authors Dr. Olaf Groth Olaf Groth, Ph.D. is co-author of “Solomon’s Code” and CEO of Cambrian.ai, a network of advisers on global innovation and disruption trends, such as AI, IOT, autonomous systems and the 4th Industrial Revolution for executives and investors. He serves as Professor of Strategy, Innovation & Economics at Hult International Business School, Visiting Scholar at UC Berkeley’s Roundtable on the International Economy, and the Global Expert Network member at the World Economic Forum. Dr. Mark Nitzberg Mark Nitzberg, Ph.D. is co-author of “Solomon’s Code” and Executive Director of the Center for Human-Compatible AI at the University of California at Berkeley. He also serves as Principal & Chief Scientist at Cambrian.ai, as well as advisor to a number of startups, leveraging his combined experience as a globally networked computer scientist and serial social entrepreneur. Mark Esposito Mark Esposito is a member of the Teaching Faculty at the Harvard University's Division of Continuing, a Professor of business and economics, with appointments at Grenoble Ecole de Management and Hult International Business School. He is an appointed Research Fellow in the Circular Economy Center, at the University of Cambridge's Judge Busines School. He is also a Fellow for the Mohammed Bin Rashid School of Government in Dubai. At Harvard, Mark teaches Systems Thinking and Complexity, Economic Strategy and Business, Government & Society for the Extension and Summer Schools and serves as Institutes Council Co-Leader, at the Microeconomics of Competitiveness program (MOC) developed at the Institute of Strategy and Competitiveness, at Harvard Business School. He is Founder & Director of the Lab-Center for Competitiveness, a think tank affiliated with the MOC network of Prof. Michael Porter at Harvard Business School and Head of the Political Economy and Sustainable Competitiveness Initiative. He researches the "Circular Economy" inside out and his work on the topic has appeared on top outlets such as The Guardian, World Economic Forum, Harvard Business Review, California Management Review, among others. He is the co-founder of the concepts of "Fast Expanding Markets" and "DRIVE", which represent new lenses of growth detection at the macro, meso and micro levels of the economy. He is also an active entrepreneur and co-founded Nexus FrontierTech, an Artificial Intelligence Studio, aimed at providing AI solutions to a large portfolio of clients. He was named one of the emerging tomorrow's thought leaders most likely to reinvent capitalism by Thinkers50, the world’s premier ranking of management thinkers and inducted into the "Radar" of the 30 most influential thinkers, on the rise. 40 Authors Terence Tse Terence is a co-founder & managing director of Nexus Frontier Tech: An AI Studio. He is also an Associate Professor of Finance at the London campus of ESCP Europe Business School. Terence is the co-author of the bestseller Understanding How the Future Unfolds: Using DRIVE to Harness the Power of Today’s Megatrends. He also wrote Corporate Finance: The Basics. In addition to providing consulting to the EU and UN, Terence regularly provides commentaries on the latest current affairs and market developments in the Financial Times, the Guardian and the Economist, as well as through CNBC and the World Economic Forum. He has also appeared on radio and television shows and delivered speeches at the UN, International Monetary Fund and International Trade Centre. Invited by the Government of Latvia, he was a keynote speaker at a Heads of Government Meeting, alongside the Premier of China and Prime Minister of Latvia. Terence has also been a keynote speaker at corporate events in India, Norway, Qatar, Russia and the UK. Previously, Terence worked in mergers and acquisitions at Schroders, Citibank and Lazard Brothers in Montréal and New York. He also worked in London as a consultant at EY, focusing on UK financial services. He obtained his PhD from the Judge Business School at the University of Cambridge. Danny Goh Danny is a serial entrepreneur and an early stage investor. He is the partner and Commercial Director of Nexus Frontier Tech, an AI advisory business with presence in London, Geneva, Boston and Tokyo to assist CEO and board members of different organisations to build innovative businesses taking full advantage of artificial intelligence technology. Danny has also co-founded Innovatube, a technology group that operates a R&D lab in software and AI developments, invests in early stage start-ups with 20+ portfolios, and acts as an incubator to foster the local start-up community in South East Asia. Innovatube labs have a team of researches and engineers to develop cutting edge technology to help start-ups and enterprises bolster their operation capabilities. Danny currently serves as an Entrepreneurship Expert with the Entrepreneurship centre at the Said Business School, University of Oxford and he is an advisor and judge to several technology start-ups and accelerators including Startupbootcamp IoT London. Danny has lived in four different continents in the last 20 years in Sydney, Kuala Lumpur, Boston and London, and constantly finds himself travelling. 41 Authors Josh Ensminger Josh Entsminger is an applied researcher at Nexus Frontier Tech. He additionally serves as a senior fellow at Ecole Des Ponts Business School’s Center for Policy and Competitiveness, a research associate at IE business school’s social innovation initiative, and a research contributor to the world economic forum’s future of production initiative. 42 Thank you for reading! Want to work together on a problem where behavior matters? Email Us: info@thedecisionlab.com Visit Us: www.thedecisionlab.com 43