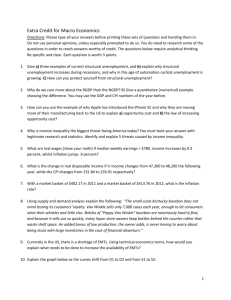

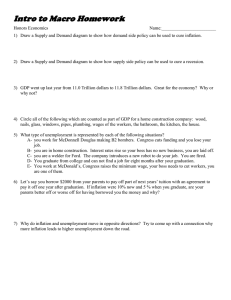

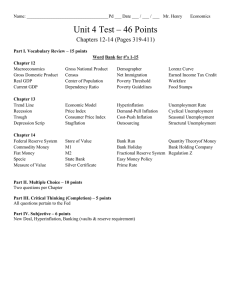

Chapter 10 - Macroeconomic objectives I: Low unemployment, low and stable rate of inflation 10.1 Low unemployment Unemployment and its measurement Unemployment refers to people of working age who are actively looking for a job but who are not employed. A closely related term is underemployment, referring to people of working age with part-time jobs when they would rather work full time, or with jobs that do not make full use of their skills and education. Examples include people who work fewer hours per week than they would like, or trained individuals, such as engineers, economists, or computer analysts, who work as taxi drivers, or waiters or waitresses, or anything else unrelated to their profession, when they would rather have a job in their profession. Both unemployment and underemployment mean that an economy is wasting scarce resources by not using them fully. In the case of unemployment this is obvious. With underemployment, working at a job other than in one’s profession also involves resource ‘waste’, because some resources that were used for training and education are wasted when people are forced to work at a job that does not make use of their skills. Calculating unemployment: the unemployment rate The labour force is defined as the number of people who are employed (working) plus the number of people of working age who are unemployed (not working but seeking work). The labour force is actually a fraction of the total population of a country, because it excludes children, retired persons, adult students, all people who cannot work because of illness or disability, as well as all people who do not want to work. Unemployment can be measured as a number or percentage: As a number, unemployment is the total number of unemployed persons in the economy, i.e. all persons of working age who are actively seeking work but are not employed. As a percentage, unemployment is called the unemployment rate, defined as: For example, if the unemployment rate in an economy is 6%, this means that six out of every 100 people in the labour force are unemployed. Underemployment can similarly be measured as a number or as a percentage. If the underemployment rate is 15%, this means that 15 out of every 100 people in the labour force are underemployed. Difficulties in measuring unemployment The unemployment rate is one of the most widely reported measures of economic activity, used extensively as an indicator of economic performance. Yet it is actually difficult to obtain an accurate measurement of unemployment. Official statistics often underestimate true unemployment because of hidden unemployment, arising from the following: ● ● ● ● Unemployment figures include unemployed persons who are actively looking for work. This excludes ‘discouraged workers’, or unemployed workers who gave up looking for a job because, after trying unsuccessfully to find work for some time, they became discouraged and stopped searching. These people in effect drop out of the labour force. Unemployment figures do not make a distinction between full-time and part-time employment, and count people with part-time jobs as having full-time jobs though in fact they are underemployed. Unemployment figures make no distinction on the type of work done. If a highly trained person works as a waiter, this counts as full employment. Unemployment figures do not include people on retraining programmes who previously lost their jobs, as well as people who retire early although they would rather be working. In addition, official statistics may overestimate true unemployment, because: ● Unemployment figures do not include people working in the underground economy (or informal economy). This is the portion of the economy that is unregistered, legally unregulated and not reported to tax authorities. Some people may be officially registered as unemployed, yet they may be working in an unreported (underground) activity. A further disadvantage of the national unemployment rate (calculated for an entire nation) is that it is an average over the entire population, and therefore does not account for differences in unemployment that often arise among different population groups i n a society. Within a national population, unemployment may differ by: ● ● ● ● ● region – regions with declining industries may have higher unemployment rates than other regions gender – women sometimes face higher unemployment rates than men ethnic groups – some ethnic groups may be disadvantaged due to discrimination, or due to lower levels of education and training age – youth unemployment (usually referring to persons under the age of 25) often face higher unemployment rates than older population groups, often due to lower skill levels; people who are ageing also sometimes face higher unemployment rates as employers may be less willing to employ them occupation and educational attainment – people who are relatively less skilled may have higher unemployment rates than more skilled workers (though in some countries higher unemployment rates may be found among highly educated groups). Calculating the unemployment rate To calculate the unemployment rate, we use the definition of unemployment together with the formula for the unemployment rate given above. Suppose there is a population of 35.5 million people, of whom 17.3 million are in the labour force, 1.5 million work part time though they would rather work full time, 0.5 million are discouraged workers, and 1.4 million are looking for work but cannot find any. What is the unemployment rate? The unemployment rate is1.4/17.3 × 100 = 8.1%, which 17.3 is the number looking for work but unable to find any divided by the size of the labour force, times 100. Note that we ignore the size of the total population (it is irrelevant), as well as the number of people who are working part-time (they are considered to be employed) and the number of discouraged workers (they are not considered to be unemployed or part of the labour force). Consequences of unemployment Unemployment of labour is one of the most important economic concerns to countries around the world, as it affects many aspects of economic and social life. Reduction of unemployment is a key objective of governments everywhere, as its presence has major economic and social consequences. Economic consequences Unemployment has the following economic consequences: ● ● ● ● ● A loss of real output (real GDP). ○ Since fewer people work than are available to work, the amount of output produced is less than the level the economy is capable of producing. ○ This is why unemployment means that an economy finds itself somewhere inside its production possibility curve, producing a lower level of output than it is capable of producing. A loss of income for unemployed workers. ○ People who are unemployed do not have an income from work ○ Even if they receive unemployment benefits, they are likely to be worse off financially than if they had been working. A loss of tax revenue for the government. ○ Since unemployed people do not have income from work, they do not pay income taxes; this results in less tax revenue for the government. Costs to the government of unemployment benefits. ○ If the government pays unemployment benefits to unemployed workers, the greater the unemployment, the larger the unemployment benefits that must be paid, and the less tax revenue left over to pay for important government-provided goods and services such as public goods and merit goods. Costs to the government of dealing with social problems resulting from unemployment. ○ ● ● The social problems that arise from unemployment often require government funds to be appropriately dealt with. More unequal distribution of income. ○ Some people (the unemployed) become poorer while others (the employed) are able to maintain their income levels. ○ Since certain population groups (ethnic groups, regional groups, etc. discussed above) may be more hard hit by unemployment than others, the effects of increasing income inequalities and resulting poverty tend to be concentrated among population groups who are more disadvantaged to begin with. ○ If unemployment is high or tends to persist over long periods of time, this may lead to increased social tensions and social unrest. Unemployed people may have difficulties finding work in the future. ○ When people remain out of work for long periods, they may not find work easily at a later time in the future. ○ This can happen because the unemployed workers may partly lose their skills due to not working for a long time, or because in the meantime new skills may be required that workers have not been able to keep up with, or because firms have found ways to manage with fewer workers. ○ This process is known as hysteresis. ○ Hysteresis suggests that high unemployment rates in the present may mean continued high unemployment rates in the future, even when economic conditions become more favourable. Personal and social consequences ● ● Personal problems. ○ Being unemployed and unable to secure a job involves a loss of income, increased indebtedness as people must borrow to survive, as well as loss of self-esteem. ○ All these factors cause great psychological stress, sometimes resulting in lower levels of health, family tensions, family breakdown and even suicide. Greater social problems. ○ High rates of unemployment, particularly when they are unequally distributed for the reasons noted earlier, can lead to serious social problems, including increased crime and violence, drug use and homelessness. Types and causes of unemployment Structural unemployment Structural unemployment occurs as a result of changes in demand for particular types of labour skills, changes in the geographical location of industries and therefore jobs, and labour market rigidities. Changes in demand for particular labour skills The demand for particular types of labour skills changes over time. This may be the result of technological change, which often leads to a need for new types of skills, while the demand for other skills falls. For example, computer technology ,the introduction of automated teller machines (ATMs). In addition, changes in demand for labour skills may occur because of changes in the structure of the economy, leading to some growing industries and some declining industries. Workers who lose their jobs in declining industries may not have the necessary skills to work in growing industries, and become structurally unemployed. For example,as the agricultural sector declines in relative importance and the manufacturing and services sectors grow, agricultural workers may lose their jobs. Workers lacking the necessary skills to work in industry or services may become structurally unemployed These kinds of changes lead to mismatches between labour skills demanded by employers and labour skills supplied by workers. Such mismatches cause structural unemployment. Changes in the geographical location of jobs When a large firm or even an industry moves its physical location from one region to another, there is a resulting fall in demand for labour in one region and an increase in the region where it relocate If people cannot move to economically expanding regions, they may become structurally unemployed. Sometimes firms relocate to foreign countries, increasing the overall structural unemployment within a country. Once again, the result will be a mismatch between labour demanded and labour supplied within a geographical region (or country). Using a diagram to show structural unemployment arising from mismatches between labour demand and labour supply Structural unemployment arising from mismatches between labour demand and supply can be shown indirectly in a product supply and demand diagram. Figure 10.1(a) shows how falling demand for a product (a shift from D1 to D2) results in a smaller quantity supplied (fall to Q2 from Q1 ). Such falling demand could be for a product produced in a declining industry, or one that was produced in a local industry that has relocated elsewhere The smaller quantity supplied means firms require less labour to produce the particular product; therefore, workers who lack skills to find a job in another industry, or workers who cannot relocate to another area become structurally unemployed. Labour market rigidities are factors preventing the forces of supply and demand from operating in the labour market They include: ● ● ● ● minimum wage legislation, which leads to higher than equilibrium wages and causes unemployment labour union activities and wage bargaining with employers, resulting in higher than equilibrium wages also causing unemployment employment protection laws, which make it costly for firms to fire workers (because they must pay compensation), thus making firms more cautious about hiring generous unemployment benefits, which increase the attractiveness of remaining unemployed and reduce the incentives to work. Although economists do not always agree on the effects of these factors on unemployment, many argue that they are responsible for higher unemployment rates in countries with strong labour protection systems (such as in Europe) compared to countries with weaker labour protection systems (such as the United States). Using diagrams to show structural unemployment arising from labour market rigidities Unemployment arising from minimum wage legislation, labour union activities and employment protection laws can be shown indirectly, through a product supply and demand diagram, as in Figure 10.1(b). Higher than equilibrium wages and employment protection lead to higher costs of production for firms, causing the firm supply curve to shift to the left, leading to a smaller quantity of output produced (Q2 instead of Q1 ). Firms therefore hire a smaller quantity of labour, and this contributes to structural unemployment of this type. Unemployment arising from minimum wages and labour union activities leading to higher than equilibrium wages, can also be shown in a labour market diagram, as in Figure 10.1(c) The higher than equilibrium wage, Wf, results in unemployment of labour equal to Qs – Qd Structural unemployment (of all types) is a serious type of unemployment because it tends to be long term. A certain amount of structural unemployment is unavoidable in any dynamic, growing economy, and is therefore considered to be part of ‘natural unemployment’. However, this does not mean that it cannot be lowered. There are many policies governments can pursue to reduce it, including measures encouraging workers to retrain and obtain new skills, and to relocate (move) to areas with greater employment opportunities; providing incentives to firms to hire structurally unemployed workers; and measures to reduce labour market rigidities. Frictional unemployment Frictional unemployment occurs when workers are between jobs. Workers may leave their job because they have been fired, or because their employer went out of business, or because they are in search of a better job, or they may be waiting to start a new job Frictional unemployment tends to be short term, and does not involve a lack of skills that are in demand It is therefore less serious than structural unemployment. A certain amount of frictional unemployment is inevitable in any growing, changing economy, where some industries expand while others contract, some firms grow faster than others, and workers seek to advance their income and professional positions. An important cause of frictional unemployment is incomplete information between employers and workers regarding job vacancies and required qualifications. Because of incomplete information, it takes time for the right applicants to get matched up with the right jobs. Therefore, frictional unemployment is part of natural unemployment. Measures to deal with frictional unemployment aim at reducing the time that a worker spends in between jobs and improving information flows between workers and employers. Seasonal unemployment Seasonal unemployment occurs when the demand for labour in certain industries changes on a seasonal basis because of variations in needs. Farm workers experience seasonal unemployment because they are hired during peak harvesting seasons and laid off for the rest of the year. The same applies to lifeguards and gardeners, who are mostly in demand during summer months, people working in the tourist industry, which varies from season to season, shop assistants, who are in greater demand during peak selling months, and many others. Some seasonal unemployment is unavoidable in any economy, as there will always be some industries with seasonal variations in labour demand. Therefore, seasonal unemployment is also part of natural unemployment Measures to deal with seasonal unemployment are similar to those for lowering frictional unemployment. Structural, frictional and seasonal unemployment: the natural rate of unemployment Since ‘full employment’ means there is unemployment equal to the natural rate, what we really mean is that when an economy has full employment, it has unemployment equal to the sum of structural, frictional and seasonal unemployment. Moreover, since the natural rate of unemployment is unemployment when the economy is producing potential output, a fall in the natural rate of unemployment is reflected by an increase in potential output, a ppearing as a rightward shift of the LRAS curve and the Keynesian AS curve. We can now see that such AS shifts can occur due to a reduction in structural, frictional or seasonal unemployment. However, note that an increase in potential output does not necessarily mean that structural, fictional or seasonal unemployment have fallen, as potential output may increase for a variety of reason Cyclical (demand-deficient) unemployment Cyclical unemployment, as the term suggests, occurs during the downturns of the business cycle, when the economy is in a recessionary gap. The downturn is seen as arising from declining or low aggregate demand (AD) , and so is also known as demand-deficient unemployment. As real GDP falls due to a fall in AD, unemployment increases because firms lay off workers. In the upturn of the business cycle, as real GDP increases, the recessionary gap becomes smaller and cyclical unemployment falls. When the economy produces real GDP at the level of potential output, there is no longer any cyclical unemployment. Although cyclical unemployment is a Keynesian concept, it can be illustrated by use of both the monetarist/new classical and Keynesian versions of the AD-AS model, shown in Figure 10.2 In both parts, the economy is initially producing potential output Yp ,with zero cyclical unemployment A fall in aggregate demand, causing AD1 to shift to AD2 , creates a recessionary gap as real output falls to Yr ec. At Yr ec, the new unemployment created is cyclical unemployment. Since cyclical unemployment arises from a deficiency of aggregate demand, measures to reduce this unemployment involve the use of government policies to increase aggregate demand, and eliminate the recessionary gap. The four types of unemployment in relation to the AD-AS m odel The four types of unemployment are shown in relation to the AD- AS m odel in Figure 10.3 At output Yp, real GDP is equal to potential or full employment GDP, where there is unemployment equal to the natural rate, or the sum of structural, frictional and seasonal unemployment, and cyclical unemployment is equal to zero. If GDP falls to any level less than Yp , there is a recessionary gap, and unemployment increases so that in addition to structural plus frictional plus seasonal unemployment there is also cyclical (demand-deficient) unemployment. If GDP increases to any level greater than Yp , there is an inflationary gap, and unemployment falls below the natural rate of unemployment. This means that some workers who were structurally, frictionally or seasonally unemployed now find jobs. However, these jobs tend to be of a short duration, because the economy does not usually remain in an inflationary gap indefinitely. The government is likely to step in with policies to bring the economy back to output level Yp, where unemployment will once again reach the natural rate. Whereas it is a simple matter to distinguish between the four types of unemployment on a theoretical level, in the real world it can be very difficult to identify and distinguish between the different types of unemployment. The labour market is in a continuous state of change, with some workers quitting their jobs, others being fired, with some unemployed workers waiting for an appropriate job and others retraining for a new job, with some firms expanding, others contracting, and with some people newly entering the labour force and others leaving. The uncertainties surrounding the causes of unemployment mean that it is not always an easy matter for governments to devise appropriate policies to lower it. Evaluating government policies to address the different types of unemployment The most important difference is between cyclical (demand-deficient) unemployment, with potential solutions in the aggregate demand side of the macroeconomy, and the natural rate of unemployment (of which structural unemployment is the most serious) with potential solutions in the aggregate supply side of the macroeconomy. 10.2 Low and stable rate of inflation Inflation and deflation Inflation is defined as a sustained increase in the general price level. When we speak of the ‘general price level’ we refer to an average of prices of goods and services in the entire economy, not to the price of any one particular good or service. ‘Sustained’ means that the general price level must increase to a new level and not fall back again to its previous lower level. Further, an increase in the general price level does not necessarily mean that prices of all goods and services are increasing; prices of some goods and services may be constant or even falling, while others are increasing. The presence of inflation indicates that prices of goods and services are increasing on average. Deflation is defined as a sustained decrease in the general price level. As in the case of inflation, deflation refers to an average of prices; it is likely to be uneven, with some prices constant or even increasing. Inflation is far more common than deflation; in fact, since the 1930s (the period of the Great Depression), most economies around the world have been experiencing a rising price level, or inflation. In our discussions of the AD-AS model, we have frequently seen increases in the price level; these indicate inflation. A change in the rate of inflation, by contrast, refers to a change in how fast the price level is rising. If the price level increases by 5% in one year and then increases by 7% the next year, this represents an increase in the rate of inflation. If the price level increases by 10% in one year and by 7% the next year, this represents a decrease in the rate of inflation, and is called d isinflation. Disinflation therefore occurs when inflation occurs at a lower rate. A fall in the rate of inflation, such as from 10% to 7%, means that the price level is increasing at a lower rate, hence is disinflation. A fall in the price level indicates that deflation is occurring. Measuring inflation and deflation The consumer price index Explain that inflation and deflation are typically measured by calculating a consumer price index (CPI), which measures the change in prices of a basket of goods and services consumed by the average household. Measures of inflation (and deflation) are obtained by use of price indice A price index is a measure of average prices in one period relative to average prices in a reference period called a base period. One of the most commonly used price indices to measure inflation is the consumer price index (CPI). The consumer price index (CPI) is a measure of the cost of living, or the cost of goods and services purchased by the typical household in an economy. It is constructed by a statistical service in each country, which creates a hypothetical ‘basket’ containing thousands of goods and services that are consumed by the typical household in the course of a year The value of this basket is calculated for a particular year (called a base year); this is done by multiplying price times quantity for each good and service in the basket, and adding up to obtain the total value of the basket. The value of the same basket of goods and services is then calculated for subsequent years. The result is a series of numbers that show the value of the same basket o f goods and services for different years. The CPI is then constructed to show how the value of the basket changes from year to year by comparing its value with the base year. Once the consumer price index is constructed, inflation and deflation can be expressed as a percentage change of the index from one year to the other, which is simply a measure of the percentage change in the value of the basket from one year to another. Since the value of the basket changes from one period to another because of changes in the prices of the goods in the basket, these percentage changes reflect changes in the average price level. A rising price index indicates inflation; a falling price index indicates deflation. CPIs and rates of change in the price level are also calculated on a monthly basis and a quarterly basis ● ● ● The consumer price index (CPI) is a measure of the cost of living for the typical household, and compares the value of a basket of goods and services in one year with the value of the same basket in a base year. Inflation (and deflation) are measured as a percentage change in the value of the basket from one year to another. A positive percentage change indicates inflation. A negative percentage change indicates deflation. Problems with the consumer price index (CPI) The CPI, we have seen, is based on a fixed basket of goods and services d efined for a particular year, meant to reflect purchases of consumer goods and services by the typical household. The use of such a basket leads to some problems: ● ● ● ● Different rates of inflation for different income earners. ○ The rate of inflation calculated by use of the CPI reflects the change in average prices of goods and services included in the basket. ○ However, different consumers have different consumption patterns depending on their income levels, and these may differ from what is included in the basket. ○ This means they face different rates of inflation than what is calculated on the basis of the CPI basket. Different rates of inflation depending on regional or cultural factors. ○ Exactly the same idea as above applies to consumer groups whose purchases differ from the typical household’s consumption patterns, because of variations in tastes due to cultural and regional factors. Changes in consumption patterns due to consumer substitutions when relative prices change. ○ Each good and service included in the basket is weighted (multiplied by the number of units of the good or service purchased by the typical household over a year). ○ However, as some goods and services become cheaper or more expensive over time, consumers make substitutions, buying more units of the cheaper goods and less of the more expensive ones. ○ This results in changing weights (number of units consumed by the typical household), but because the weights in the basket are fixed, the changes in consumption patterns cannot be accounted for in the CPI. ○ Therefore, the CPI gives a misleading impression of the degree of inflation, usually overstating it. Changes in consumption patterns due to increasing use of discount stores and sales. ○ In many countries, consumers increasingly make use of discount stores and sales, thus buying some goods and services at lower prices than those used in CPI calculations. ● ● ● ● ○ This is another reason why the CPI tends to overstate inflation. Changes in consumption patterns due to introduction of new products. ○ In this case, too, a fixed basket of goods and services cannot account for new products introduced into the market, as well as older products that become less popular or are withdrawn (consider for example the replacement of videotapes by DVDs). Changes in product quality. ○ This is another problem related to the use of a fixed basket of goods and services. ○ The CPI cannot account for quality changes over time. International comparisons. ○ The CPIs of different countries differ from each other with respect to the types of goods and services included in the basket, the weights used and methods of calculation. ○ This limits the comparability of CPIs and inflation rates from country to country. ○ To address this problem, the European Union (EU) has devised a Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). ○ The HICP determines consistent and compatible rules that must be followed by EU countries in order to calculate CPIs that are consistent with each other. Comparability over time. ○ Virtually all countries around the world periodically revise their CPI baskets and change the base year (usually about every ten years) to try to deal with many of the problems noted above. ○ In many countries the weights of goods and services are changed as often as every year. ○ This means that whereas price index numbers are comparable over short periods of time, over longer periods comparability is lessened because of cumulative changes in the basket of goods and services. The core rate of inflation There are certain goods, notably food and energy products (such as oil) that have highly volatile prices (meaning they fluctuate widely over short periods of time). Reasons for price volatility include wide swings in supply or demand, causing large and abrupt price changes. When such goods are included in the CPI, they may give rise to misleading impressions regarding the rate of inflation. To deal with this problem, economists measure a core rate of inflation, which usually is done by constructing a CPI that does not include food and energy products with highly volatile prices. The producer price index (PPI) The producer price index (PPI) is actually several indices of prices received by producers of goods at various stages in the production process. For example, there is a PPI for inputs, a PPI for intermediate goods and a PPI for final goods (at the wholesale level, not retail). PPIs measure price level changes from the point of view of producers rather than consumers. Price level changes measured by PPIs are considered to be predictors of changes in the consumer price index (CPI) and hence predictors of the rate of inflation, because they measure price changes at an earlier stage in the production process. For example, if prices of inputs or intermediate prices are rising, it is likely that the prices of the final products paid by consumers will also rise at a later date. Also, if wholesale prices are rising, that also indicates that the higher prices will eventually be Consequences of inflation Inflation, and especially a high rate of inflation, poses problems for an economy, because it affects particular population groups especially strongly, as well as the economy as a whole. The relationship between inflation, purchasing power and nominal and real income To understand why problems can arise, let’s consider the relationship between inflation and purchasing power, and nominal and real income Purchasing power refers to the quantity of goods and services that can be bought with money Imagine you have £60 to spend on shirts. You can think of this as your ‘nominal income’. When the price is £20 per shirt, you can buy three shirts. If the price increases to £30 per shirt, you can only buy two shirts. Your money, or your nominal income of £60 has not changed, yet the purchasing power of the £60, or what this money can buy, has fallen due to the increase in price. ‘Real income’ is the same as ‘purchasing power’; it refers to what your money can buy: it decreases as prices rise, and increases as prices fall. Changes in real income, money income and the general price level are related to each other in the following way: % change in real income (or purchasing power) = % change in nominal income−% change in the price level (or the rate of inflation) Inflation leads to a fall in real income, or purchasing power, only if nominal income is constant, or if nominal income increases more slowly than the price level. Say there is a 5% increase in the price level, which is a 5% rate of inflation. How will your real income be affected? If your nominal income also increases by 5%, your real income, or purchasing power, remains unchanged. Therefore, for you, inflation is not a problem. If, however, your nominal income remains constant or increases by less than 5%, your real income falls, and you will be worse off since the purchasing power of your income is reduced. Consequences of inflation Redistribution effects Inflation redistributes income away from certain groups in the economy and towards other groups. Redistribution arises in situations where certain groups lose some purchasing power and become worse off, while other groups gain purchasing power and become better off. Groups who lose from inflation include: landlords receive fixed rental income individuals receive fixed welfare payments. ● ● ● ● People who receive incomes or wages that increase less rapidly than the rate of inflation. ○ When individuals’ incomes do not keep up with a rising price level (do not increase as fast as the price level), a fall in their real incomes results and they therefore become worse off. ○ These groups may include all those noted above plus any other kind of income receiver whose income is not increasing as rapidly as the price level. Holders of cash. ○ As the price level increases, the real value or purchasing power of any cash held falls. Savers. ○ People who save money may become worse off as a result of inflation. In order to maintain the real value of their savings, savers must receive a rate of interest that is at least equal to the rate of inflation. ○ In general, savers who receive a rate of interest on their savings lower than the rate of inflation suffer a fall in the real value (or purchasing power) of their savings. Lenders(creditors). ○ People who lend money may be worse off due to inflation. ○ In general, lending at a lower interest rate than the rate of inflation makes the lender (creditor) worse off at the end of the loan period. Groups who gain from inflation include: ● ● ● Borrowers (debtors). ○ In general, borrowing at a lower interest rate than the rate of inflation makes the borrower (debtor) better off at the end of the loan period. Payers of fixed incomes or wages. ○ As long as nominal wages, pensions, rents, welfare payments, etc., are fixed while there is inflation, the payers (whether they are firms, the government, payers of rent, etc.) benefit as the real value of their payments falls due to inflation. Payers of incomes or wages that increase less rapidly than the rate of inflation. ○ As long as incomes of any kind increase less rapidly than the rate of inflation, the payers of these incomes benefit due to the falling real value of their payments. Uncertainty Inability to accurately predict what inflation will be in the future means that people cannot predict future changes in purchasing power (of income, wealth, loans and anything else that is measured in terms of money). This causes uncertainty among economic decision- makers. Firms, in particular, become more cautious about making future plans under uncertainty about future price levels, because they are unable to make accurate forecasts of costs and revenues, as these depend on the future prices of their inputs and their products. Their uncertainty leads them to make fewer investments, which in turn may lead to lower economic growth. Menu costs Menu costs are costs incurred by firms when they have to print new menus (in restaurants), catalogues, advertisements, price labels, etc., due to changes in prices. The higher the rate of inflation, the more often firms have to change their prices and therefore, the higher the menu costs. Money illusion Money illusion refers to the idea that some people feel better off when their nominal income increases, even though the price level may increase at the same rate and possibly even faster. When this occurs, people are under the illusion that they are better off whereas in fact they are not: their real income or purchasing power has not changed at all, and may even have decreased. If money illusion is widespread, it has negative consequences because it leads consumers to make wrong spending decisions. International (export) competitiveness When the price level in a country increases more rapidly than the price level in other countries with which it trades, its exports become more expensive to foreign buyers, while imports become cheaper to domestic buyers. The country’s international competitiveness, or its ability to compete with foreign countries, is reduced. The result is that the quantity of exports falls, and the quantity of imports increases This in turn may create difficulties for the country’s balance of payments Consequences of hyperinflation (supplementary material) Hyperinflation consists of very high rates of inflation. It is defined as occurring when the price level increases by more than 50% per month, though it can reach thousands or even millions of percentage points per year. In more recent years, many hyperinflations have been concentrated in Latin America from the mid-1980s to early 1990s Hyperinflation results from very significant increases in the supply of money, which impact directly on the price level. Hyperinflations occur when governments resort to printing money, thereby increasing its supply. Hyperinflation has serious negative consequences, over and above those discussed above, because money loses its value very rapidly. Consumers increase their spending to benefit from the current lower prices, thereby feeding aggregate demand. Workers demand higher nominal wages to maintain the real value of their current and future incomes, thereby feeding cost- push inflation. Therefore, an inflationary spiral is created (a process where inflation sets in motion a series of events that worsen the inflation). Serious hyperinflations result in a massive disruption of economic activity: businesses stop investing in productive activities and invest instead in assets that are believed to maintain their value as prices rise (gold, real estate or jewels); firms also withhold goods from sale in the market so that they can sell them later at higher prices; lenders (creditors) suffer massive losses as the real value of debts falls dramatically. At the extreme, money loses its value altogether and people resort to barter (the direct exchange of goods or services, eliminating the need for money), which in itself makes production and exchange extremely difficult. Serious hyperinflations can also lead to political and social unrest. What is an appropriate rate of inflation? Most governments prefer a low and stable rate of inflation, not a zero rate of inflation. Why is a zero rate of inflation, meaning a constant price level, not the preferred objective? The reason is that a zero rate of inflation comes dangerously close to deflation, which as we will see below can cause serious problems for an economy. There is no one particular rate of inflation that is ideal, but many governments would like to see this in the range of about 2–3% per year. Less than 2% might be considered as coming close to deflation; more than 4% is seen as being too high. Types and causes of inflation Demand-pull inflation Demand-pull inflation involves an excess of aggregate demand o ver aggregate supply at the full employment level of output, and is caused by an increase in aggregate demand. It is shown in the AD-AS model as a rightward shift in the AD curve. Assume the economy is initially at full employment equilibrium, producing potential GDP, shown as Yp in Figure 10.4 parts (a) and (b). The economy experiences an increase in aggregate demand appearing as a rightward shift of the AD curve from AD1 to AD2 in both diagrams. The impact on the economy is to increase the price level from Pl1 to Pl2 , and to increase the equilibrium level of real GDP from Yp to Yinfl. The increase in the price level from Pl1 to Pl2 due to the increase in aggregate demand is known as demand-pull inflation. Note that demand-pull inflation is associated with an inflationary gap: real GDP is greater than full employment GDP, and unemployment falls to a level below the natural rate of unemployment. The demand for labour is so large that some workers who are structurally, frictionally or seasonally unemployed temporarily find jobs. Cost-push inflation Cost-push inflation is caused by a fall in aggregate supply, in turn resulting from increases in wages or prices of other inputs, shown in the AD- AS model as leftward shifts of the AS curve. Assume the economy is initially at the full employment level of output, Yp in Figure 10.5, and suppose there is an increase in costs of production. The SRAS curve shifts from SRAS1 to SRAS2 , leading to an increase in the price level from Pl1 to Pl2, and a fall in the equilibrium level of real GDP from Yp to Yr ec The increase in the price level due to the fall in SRAS i s known as cost-push inflation. Cost-push inflation is analysed only by means of the monetarist/new classical AD- AS model. The Keynesian model is not equipped to deal with short- term fluctuations of aggregate supply. Keynes was concerned with showing the importance of aggregate demand in causing short-term fluctuations. The output level Yr ec, though indicating a recession, is not called a recessionary/deflationary gap, because output gaps (whether recessionary or inflationary) can only be caused by too little or too much aggregate demand The presence of both inflation and unemployment is called stagflation, a combination of the words ‘stagnation’ and ‘inflation’. This should be contrasted with an increase in aggregate demand leading to demand-pull inflation, which results in a higher price level but an increase in real GDP Consequences and causes of deflation Why deflation occurs rarely in the real world Deflation is not a common phenomenon. Whereas it is often the case that the price of a particular good or service may fall over time, it is rare to see the general price level of an economy falling. There are several factors that account for this: ● ● ● Wages of workers do not ordinarily fall. ○ This means it is difficult for firms to lower the prices of their products, as this would cut into their profits, especially since wages represent a large proportion of firms’ costs of production. ○ There are several reasons why wages do not fall easily (labour contracts, minimum wage legislation, worker and union resistance to wage cuts, ideas of fairness, fears of negative impacts on workers’ morale, etc.). Large oligopolistic firms may fear price wars. ○ If one firm lowers its price, then others may lower theirs more aggressively in an effort to capture market shares, and then all the firms will be worse off. ○ Therefore, firms avoid cutting their prices. Firms want to avoid incurring menu costs resulting from price changes, ○ particularly if they believe that the lower prices will prevail only for short periods of time. Therefore, they avoid lowering their prices. ○ Deflation is generally feared more than inflation, because it may pose potentially serious problems for an economy. The negative consequences of deflation are discussed below. Consequences of deflation Redistribution effects The redistribution effects of deflation are the opposite of those of inflation: with a falling price level, individuals on fixed incomes, holders of cash, savers and lenders (creditors) all gain as the real value of their income or holdings increases. By contrast, borrowers (debtors) and payers of individuals with fixed incomes lose with a falling price level, as they must pay out sums that have an increasing real value. Uncertainty Deflation, like inflation, creates uncertainty for firms, which are unable to forecast their costs and revenues due to declining price levels. Menu costs Menu costs (the costs to firms of printing new menus, catalogues, advertisements, price labels, etc.) are similar in the case of deflation as in the case of inflation, as both simply involve changes in prices. Risk of a deflationary spiral with high and increasing cyclical unemployment A deflationary spiral involves a process where deflation sets into motion a series of events that worsen the deflation. Deflation discourages spending by consumers, because they postpone making purchases as they expect that prices will continue to fall. Deflation also discourages borrowing by both consumers and firms, for the reason noted above: the real value of debt increases as the price level falls. The result is that consumer and business spending falls, causing aggregate demand to fall. If the economy is already in recession, this will become deeper with falling AD, unemployment increases further, incomes and prices fall further, deflationary pressures increase further, spending and borrowing decrease further, and so on in a downward spiral. Risk of bankruptcies and a financial crisis As we saw above, deflation results in an increase in the real value of debt. If the economy is in recession, and incomes are falling while the real value of debt is increasing, the result will most likely be bankruptcies of firms and consumers who are unable to pay back their debts If such bankruptcies become widespread, banks and financial institutions will be affected, and a large risk of a major financial crisis arises. The last two items, risks of a deflationary spiral and a financial crisis, reveal the special and potentially serious dangers of deflation. Causes of deflation From an analytical point of view, we can make a distinction between two causes of deflation: decreases in aggregate demand, held to lead to a ‘bad’ kind of deflation, and increases in aggregate supply, held to lead to ‘good’ deflation. To see how ‘bad’ deflation could arise, suppose the economy is at a point of long run equilibrium as in and assume there is a decrease in aggregate demand (for example, due to business pessimism) so that the AD curve shifts from AD1 to AD2. Whereas the AD-AS m odel predicts a drop in the price level, or deflation, this is unlikely to occur over a short period of time for the reasons discussed above, accounting for the highly However if low aggregate demand persists over a long period, the infrequent occurrence of deflation. price level falls to P2 . This is ‘bad’ deflation because it is associated with recession, falling incomes and output, and cyclical unemployment. These are the circumstances that characterised the deflation of the Great Depression during the 1930s, and more recently in Japan. ‘Good’ deflation, on the other hand, can be shown in a diagram to be caused by a rightward shift of the LRAS curve, with the AD curve constant (or also shifting to the right but by less than the LRAS shift), so that the new point of equilibrium occurs at a lower price level. This is held to be ‘good’ deflation because it is associated with economic expansion, rising incomes and output, increasing employment and economic growth. Some economists argue that it was under such circumstances that the deflation of Britain and the United States in the late 19th century occurred. The fear in 2003 that deflation might occur possibly involved both kinds of deflation. It was held that the downward pressure on prices was due partly to advances in information technology (causing an increase in aggregate supply) and partly to falls in aggregate demand. However, it must be stressed that while it may be possible to make an analytical distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ deflation, no deflation is ever good. An important reason is that as we have seen above, deflation discourages spending because it reduces borrowing due to increases in the real value of debt, and also because consumers postpone purchases in the expectation that prices will fall. These factors cause aggregate demand to fall regardless of the causes of deflation. For these reasons, deflation is generally feared and is considered by economists to be a greater threat than inflation. 10.3 Topics on inflation Constructing a weighted price index and calculating the rate of inflation We will construct a consumer price index (CPI) for a simple economy where consumers typically consume three goods and services: burgers, DVDs and haircuts, shown in column 1 of Table 10.1. Column 2 gives us the quantities of each that the typical household buys in a year; these are the weights. Note that a weighted price index is a price index that ‘weights’ the various goods and services according to their relative importance in consumer spending. To construct a 1 Decide which of the years will be the base year; we choose 2009. 2 Use the price of each good and service in the base year (2009), to calculate its base year value (multiply quantity in column 2 by 2009 prices in column 3); these values appear in column 4. 3 Add up all values in column 4 to get the total value of the basket in the base year; this is $756, appearing at the bottom of column 4. 4 Use the price of each good and service in 2010 to calculate its 2010 value (multiply the number of units in the basket (column 2) by 2010 prices (column 5)); then do the same using 2011 prices (column 7); the resulting values appear in column 6 for 2010 and column 8 for 2011. 5 Add up the values in column 6 to obtain the total value of the basket in 2010; this is $798 appearing at the bottom of column 6; do the same to find the value of the basket in 2011, which is $900, appearing at the bottom of column 8. We now have all the information we need to construct our price index for 2009, 2010 and 2011. Note that: Using the price index constructed above, we can calculate the rate of inflation (the percentage change in the price level). The percentage change in a variable A i s calculated by the following: To calculate the percentage change in the price level from 2009 to 2010, we have Therefore, it follows that the rate of inflation in the period 2009–11 is 119.0 − 100.0 = 19.0% However, it is only possible to read off the rate of inflation from a price index in this simple way in those cases involving a percentage change in the price level relative to the base year, whose price index number is equal to 100. Note that a price index with increasing values over time (such as the example above) indicates inflation. Decreasing values over time indicate deflation. Also, note that the first year in a price index need not be the base year Calculating real income In Chapter 8, we learned how to calculate real GDP from nominal GDP using the GDP deflator (page 228). We can now use the CPI to calculate real income (of consumers, pensioners, or other social groups): Clearly, if nominal income increases by the same percentage as the price level (measured by the CPI), real income remains unchanged. The CPI is, in fact, very useful for calculating adjustments that must be made to nominal income (of wage-earners, pensioners, etc.) in order for these groups to maintain a constant or increasing real income. Since the CPI compares price levels based on goods and services in a specific basket, it only makes sense to calculate inflation rates from a price index constructed by use of the same basket. Further, it is not possible to make comparisons of price levels (i.e. calculate rates of inflation) across years by use of price indices that have a different base year, even if the basket of goods and services is the same. Therefore, for comparisons of index numbers to be meaningful, the index numbers must be calculated using the same base year, and for the same basket of goods and services. The rate of inflation based on the GDP deflator is calculated in the same way as with the consumer price index. In our example the average price level of goods and services included in GDP increased by 18.8% in 2001–2 (= 118.8−100.0), and by 30.0% in 2001–3 (= 130.0−100.0). The rate of increase in the period 2002–3 is: Comparing the CPI with the GDP deflator ● ● The GDP deflator includes irrelevant goods from the consumer’s perspective and excludes imports. The GDP deflator does not allow goods and services to be weighted in accordance with their relative importance in the typical household’s budget. Possible relationships between unemployment and inflation The Phillips curve The Phillips curve is concerned with the relationship between unemployment and inflation. The relationship showed that the lower the rate of inflation, the higher the unemployment rate; and the higher the rate of inflation, the lower the unemployment rate. This relationship is shown in Figure 10.6(a), where the unemployment rate is measured along the horizontal axis, and the rate of inflation along the vertical axis. The Phillips curve suggests that if there is a constant negative relationship between the two variables, then every economy faces a trade-off between inflation and unemployment: it can choose between a relatively low rate of inflation and a higher unemployment rate, such as point a on the curve, or a higher rate of inflation and a lower unemployment rate, such as point d. Whereas,ideally, it would be preferable for any economy to have low inflation and low unemployment, such as point e, this is not possible according to the theory of the Phillips curve, as the only achievable points are those on (or close to) the curve. The reasoning behind the shape of the curve can be illustrated by use of the AD-AS m odel, shown in Figure 10.6(b). Assume a fixed, upward-sloping SRAS c urve, and imagine a succession of aggregate demand increases (which could be caused by any of the factors. As aggregate demand shifts from AD1 to AD2 , the price level rises from Pl1 to Pl2 , the level of real GDP increases from Y1 to Y2, and the level of unemployment correspondingly falls. The same process is repeated as aggregate demand increases from AD2 to AD3 , and then to AD4 , and so on. With every increase in aggregate demand, we have an increase in the price level and a fall in unemployment It follows, then, that we can simply think of each point on the Phillips curve (such as a, b, c or d) as corresponding to the point of intersection of SRAS w ith a different AD curve (a, b, c or d). The ‘choice’ of where to be on the Phillips curve in part (a) thus corresponds to a ‘choice’of AD curve in part (b) of the figure The breakdown in the relationship: stagflation During the 1960s, many economists came to believe that the Phillips curve did offer the possibility of choice between inflation and unemployment. At that time aggregate supply was relatively stable, and major changes in economic activity were caused by swings in aggregate demand. Most economists at the time were very strongly influenced by Keynesian thinking, believing that demand-side policies were very important in influencing the level of economic activity and real GDP. The Phillips curve appeared to offer governments the possibility of using demand-side policies to choose between various alternatives. High aggregate demand would lead to low unemployment and higher inflation, while low aggregate demand would lead to higher unemployment and lower inflation. Events of the 1970s and 1980s upset this line of thinking, and the stable relationship between inflation and unemployment that was suggested by the Phillips curve appeared to break down Whereas it had been supposed that aggregate supply could remain stable over long periods of time, a number of aggregate supply shocks led to a period of stagflation, a term coined at the time to refer to the new phenomenon of stagnation (or recession) with unemployment and inflation simultaneously. The most important of the supply shocks involved the oil price increases brought on by the actions of OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries), which restricted the global supply of oil). Another supply shock involved food price increases resulting from worldwide crop failures (restricting the global supply of food). The impacts of these events on the Phillips curve and on the SRAS c urve are shown in Figures 10.7(a) and (b). In part(b), we see that as the supply shocks cause the SRAS curve to shift leftward from SRAS1 to SRAS2 and then to SRAS3, the result is higher price levels (from Pl1 to Pl2 and Pl3 ) and lower levels of GDP (from Y1 to Y2 and Y3 ), signifying increases in unemployment. In other words, decreases in SRAS ( with AD constant) result in higher price levels and higher unemployment. This phenomenon is inconsistent with the logic of the Phillips curve, and was interpreted to involve outward shifts in the Phillips curve, which until then was thought to be stable and constant. The outward Phillips curve shifts appear in part(a), indicating that higher rates of inflation are associated with higher rates of unemployment; the moves from point a to b and c in part (a) correspond to points a, b and c in part (b). The long-run Phillips curve and the natural rate of unemployment In the late 1970s, the Nobel Prize-winning, monetarist economist Milton Friedman attacked the idea of a stable negative relationship between inflation and unemployment, and argued that there is only a temporary trade-off between inflation and unemployment, not a permanent one. Friedman made a distinction between a short-run Phillips curve and a long-run Phillips curve. The short-run Phillips curve is what we have considered above in Figure 10.6(a), which we can see once again in Figure 10.8(a), represented by SRPC1 and SRPC2. According to Milton Friedman, in the long run, this negative relationship no longer holds. Instead, the long-run Phillips curve is vertical at the level of ‘full employment’, or where unemployment equals the natural rate of employment. The long-run Phillips curve is LRPC i n Figure 10.8(a). Why is the long-run Phillips curve vertical at the economy’s natural rate of unemployment? The answer is quite simple: it is so for the same reasons that the LRAS curve is vertical at the level of real GDP corresponding to the natural rate of unemployment. Consider Figure 10.8, and suppose the economy is initially at point a in both parts In part (b), point a indicates that the economy is at a point of long-run equilibrium on AD1 , SRAS1 and the LRAS curve, with real GDP equal to potential GDP shown byYp. At Yp, unemployment is equal to the natural rate of unemployment, which we assume to be 5%. In part (a), point a indicates that the economy is on a short-run Phillips curve, SRPC1 , where it is experiencing a rate of inflation of 5% and unemployment of 5%, or the natural rate of unemployment. Suppose there occurs an increase in aggregate demand, so that the AD curve in part (b) shifts from AD1 to AD2 . In the short run the economy moves to point b on the SRAS1 curve, corresponding to a higher price level, Pl2 , increased real GDP, Yi nfl, and lower unemployment (unemployment falls below the natural rate). This corresponds to point b on the SRPC1 in part (a), where there is a higher inflation rate of 7% and lower unemployment at 3%. The economy moved to point b in the short run, because in the short run wages are constant; with the price level increasing, firm profitability increases, output increases and unemployment falls. But in the long run, point b cannot be a point of equilibrium, wages will rise to meet the increases in the price level, causing the SRAS curve to shift leftward from SRAS1 to SRAS2 , where it intersects AD2 at a point on the LRAS curve, or point c. Point c in part (b) is associated with a higher price level Pl3 , but real GDP has fallen back to Yp, and the rate of unemployment has returned to the natural rate In part (a), these changes mean the economy has moved to point c, where the short-run Phillips curve has shifted to the right to SRPC2 (remember, when the SRAS curve shifts leftward with a constant AD curve, the SRPC c urve shifts rightward, as we saw in Figure 10.7). At point c, there is a higher rate of inflation, now standing at 9%, and unemployment has climbed back up to 5%, or the natural rate. The vertical line connecting a and c is the long-run Phillips curve (LRPC), situated at the natural rate of unemployment. According to the short-run Phillips curve in Figure 10.6(a), there is a negative relationship between the rate of inflation and the unemployment rate, suggesting that in the short run policy-makers can choose between the competing alternatives of low inflation or low unemployment by using policies that affect aggregate demand. The long- run Phillips curve is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment, indicating that unemployment is independent of the rate of inflation, and that policy-makers do not have a choice between the two competing alternatives. In the long run, the only impact of an increase in aggregate demand is to increase the rate of inflation, while the level of real output and unemployment remain unchanged at the natural rate of unemployment. The short-run Phillips curve is a tool preferred by Keynesian economists, who see in this the possibility of using policies that focus on influencing aggregate demand to make choices about the rate of inflation and the rate of unemployment (and therefore the level of real GDP). By contrast, the long-run Phillips curve is an analytical tool preferred by monetarist/new classical economists, who are highly skeptical about the effectiveness of demand-side policies, and who use it to show that expansionary demand-side policies are more likely to result in inflation than to influence unemployment and real GDP.