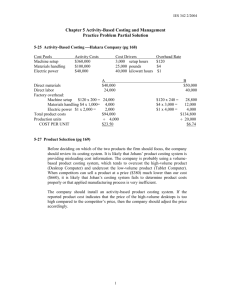

Chapter 7: Activity-Based Costing: A Tool to Aid Decision Making A. Traditional costing systems in manufacturing companies, such as those discussed in Chapters 5 (job-order costing) and 6 (process costing), are primarily designed to provide product cost data for external financial reports rather than for internal decision making. 1. For external financial reports, all manufacturing costs must be assigned to products—even manufacturing costs that are not actually caused by any particular product. For example, the rent on the factory building is the same (within limits) regardless of which products are produced and how much is produced, and yet this cost must be assigned to products for external financial reports. 2. For external financial reports, non-manufacturing costs (selling and administrative costs) are not assigned to products, even if the products directly cause the costs. For example, sales commissions are not included in product costs in traditional costing systems even though sales commissions are directly caused by selling specific products. 3. Because all manufacturing costs must be assigned to products for external financial reports, the costs of idle capacity must also be assigned to products. As a consequence, products are charged for the costs of resources they don’t use as well as for the costs of resources they do use. 4. In traditional costing systems, overhead costs are usually allocated to products using a single measure of activity such as direct labour-hours. This approach assumes that overhead costs are highly correlated with direct labourhours; that is, it assumes that overhead costs and direct labour-hours tend to move together. If this assumption is not valid, product costs will be distorted. B. Activity-based costing (ABC) attempts to remedy these deficiencies of traditional costing systems. The key concept in activity-based costing is that products (and customers) cause activities. These activities result in the consumption of resources, which in turn result in costs. Consequently, if we want to accurately assign costs to products and customers, we must identify and measure the activities that link products and customers to costs. C. The distinction between manufacturing and non-manufacturing costs is critical in traditional costing systems. This distinction is much less important in activity-based costing. Like variable costing, activity-based costing is concerned with how costs behave. And like variable costing, activity-based costing is primarily used in internal reports and is intended to help managers make decisions. D. A significant number of companies have experimented with some form of activity based costing. Activity based costing originated in manufacturing companies, but is now being widely applied in service companies as well. E. Activity-based costing differs from traditional costing in a number of ways: 1. Non-manufacturing costs, as well as manufacturing costs, may be assigned to products. 2. Some manufacturing costs—the costs of idle capacity and organizationsustaining costs—may be excluded from products. 3. A number of activity cost pools are used in activity-based costing. Each cost pool has its own unique measure of activity that is used as the basis for allocating its costs to products, customers, and other cost objects. a. An activity is an event that causes consumption of overhead resources such as processing a purchase order. b. An activity cost pool is a “bucket” in which costs are accumulated that relate to a single activity such as processing purchase orders. 4. The allocation bases in activity based costing (i.e., measures of activity) often differ from those used in traditional costing systems. There are two types of activity measures (also known as transaction drivers): a. Transaction drivers which are simple counts of the number of times an activity occurs. An example would be the number of machine set-ups. b. Duration drivers are measures of the amount of time needed to perform an activity. An example would be the length of time it takes to set up machines for a production run. Duration drivers are more accurate. 5. The overhead rates in activity-based costing (which are called activity rates), may be based on the level of activity at capacity rather than on the budgeted level of activity. F. Implementing activity-based costing involves five steps: 1. Identify and define activities, activity cost pools, and activity measures. 2. Assign overhead costs to activity cost pools. 3. Calculate activity rates, which function like predetermined overhead rates in a traditional costing system. 4. Assign overhead costs to cost objects using the activity rates and measures of activity. 5. Prepare management reports. G. To more fully understand activity-based costing, it is useful to think in terms of a hierarchy of costs: 1. Unit-level activities are performed each time a unit is produced. An example is testing a completed unit. 2. Batch-level activities are performed each time a batch is handled or processed. For example, tasks such as placing purchase orders and setting up equipment are batch-level activities. These activities occur no matter how many units are produced in a batch. 3. Product-level activities are required to have a product at all. An example is maintaining an up-to-date parts list and instruction manual for the product. These activities must be performed regardless of how many batches are run or units produced. 4. Customer-level activities relate to specific customers and include sales calls and catalogue mailings that are not tied to a specific product. 5. Organization-sustaining activities are carried out regardless of which customers are served, which products are produced, how many batches are run, or how many units are produced. Examples include providing a computer network for employees, preparing financial reports, providing legal advice to the board of directors, and so on. Organization-sustaining costs should not be allocated to products or customers for purposes of making decisions. H. To understand the mechanics of activity-based costing, there is no good substitute for working through the example in the book step-by-step. Nevertheless, the process can be briefly summarized as follows: 1. Prepare the first-stage allocation of costs to the activity cost pools. a. Begin with a listing of the costs that will be included in the activitybased costing system and the results of interviews with employees that indicate how these costs are to be distributed across the activity cost pools. The interview results indicate what percentage of a specific cost such as indirect factory wages should be allocated to the first activity cost pool, the second activity cost pool, and so on. b. For example, the results of the interviews might indicate that 20% of the resources associated with office staff wages are consumed in processing purchase orders. If office staff wages are $200,000, then 20% of $200,000, or $40,000, would be allocated to the “processing purchase orders” activity cost pool. 2. Calculate the activity rates. a. An activity rate is a cost per unit of activity. For example, the activity rate for machine setups might be $14 per machine setup. b. Suppose that 2,000 purchase orders are processed per year. If the total cost of processing purchase orders is $60,000 per year, then the average cost would be $30 per purchase order ($60,000 ÷ 2,000 = $30). This is the activity rate for the “processing purchase orders” activity cost pool. c. Activity rates are important in activity-based management. Activity rates can be compared across organizations or across different locations in the same organization. For example, the cost of $30 for processing a purchase order may be higher at some locations in a company and lower at others. The higher cost locations may learn how to better process purchase orders by studying the techniques used at the lower cost locations. 3. Prepare the second-stage allocation of costs to products, customers, and other cost objects. For example, if a product requires two purchase orders and the activity rate is $30 per purchase order, the product would be allocated $60 (2 purchase orders × $30 per purchase order). Sum the costs of all of the activities associated with the product to determine the total cost of the product. I. Product costs computed under activity-based costing and traditional costing systems differ for a number of reasons. They differ in what costs are allocated to products as well as in how they are allocated. Focusing just on how the costs are allocated, some general patterns emerge. 1. An activity-based costing system typically shifts costs from high-volume products that are produced in large batches to low-volume products that are produced in small batches. Traditional costing systems apply batch-level and product-level costs uniformly to all products and the high-volume products absorb the bulk of such costs. In an activity-based costing system, such costs are assigned to the products that cause the costs, rather than spreading them uniformly over all products on the basis of volume. 2. The unit costs of the low-volume products usually increase more than the unit costs of the high-volume products decrease. The reason is that if X dollars are shifted from high-volume products to low-volume products, the cost savings for the high-volume products is spread over many units, whereas the in-crease in costs for the low-volume products is spread over few units. What To Watch Out For (Hints, Tips and Traps) Whenever possible, trace costs directly to activities and cost objects. For example, direct materials and direct labour costs are often traced directly to products and are not included in the activity based costing system. In an activity-based costing system, overhead costs can include both manufacturing and non-manufacturing costs (product and period costs) but does not have to include all manufacturing overhead as in a traditional costing system. However, a traditional costing system would include all manufacturing overhead costs and would exclude all non-manufacturing overhead costs. In contrast with a traditional costing system, some manufacturing overhead costs (such as the costs of idle capacity and organization-sustaining costs) are accumulated in a separate activity cost pool (the “other” cost pool as referred to in the text) and this cost pool is not allocated to the cost objects (products, customers, etc). Since it is not allocated to the products, it cannot be included in the product cost and will not be considered an inventoriable cost, instead, it is included as a cost on the income statement (similar to a period cost).