Linguistics Made Easy: An Introduction to Language Study

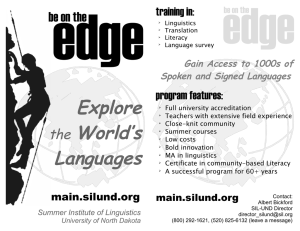

advertisement