Managerial Economics Introduction: Origins & Resource Allocation

advertisement

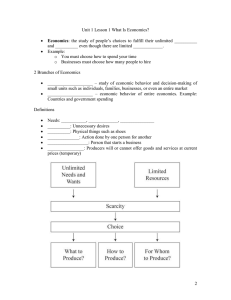

Topic 1: An Introduction to Managerial Economics Over the last two centuries, Economics has evolved as a formal discipline, putting in place some common, general rules that help manage resources better. As the discipline of Management evolved, Economics became an integral part in its curriculum and tools of Economics that needed to be taught to managers are now loosely classified as Managerial Economics. Before we start with a formal discussion of Managerial Economics it will be interesting to learn something about the origins of Economics. On the Origins of Economics Adam Smith Thomas Mun Picture downloaded from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Smith#/media/File:Adam_Smith_The_Muir_portrait.jpg Adam Smith is usually acknowledged to frame as the person who presented Economics as a formal discipline as we know of it today. His book titled, “An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations” written in 1776, created quite a storm in the prevailing philosophy of those times. The philosophy prevalent then was called the Mercantilist Philosophy1 which advocated that the wealth of nations emerged from trade, and for that an export surplus was needed, which would bring in precious metals like gold and silver into the economy. Do remember that gold and silver were the standard currency then for exchange. Remember, this was also the time that East India Company had its trade with India, and the British Crown objected to the trade with India it was a drain of precious metals from the economy in exchange for the spices and textiles obtained from India. Thomas Mun the then Director of the East India Company defended the trade with India on the grounds that that England was re-exporting the goods obtained from India to other countries and bringing back a lot more precious metails into the country than that given to India. Going by the Mercantilist Philosophy, in order to have an export surplus, the exports of the country should be cheap, for it to be cheap, wages had to be low, and if wages were low, a large section of the population would have a meagre standard If you are interested in the History of Economic Thought, read the book titled, “A history of Economic thought” by Eric Roll. 1 Managerial Economics Page 1 of living. Not only that Mercantilists assumed the size of the pie to be fixed, if one country grabbed a larger share of the pie, the other country necessarily would have a much smaller share. Adam Smith, in contrast was of the view that the wealth of nations emerged from production rather than trade. Remember this was also the time that industrial revolution was going on in England, and with industrial revolution there was a shift from home production to factory production. With factory production, there was division of labour, in the first chapter of Adam Smith’s book talk of how division of labour in a pin factory, leads to a huge increase in productivity. If there were to be division of labour and specialization, the size of the pie would increase, and it will be possible for all parties to be better off. Over time Economics branched into two major sub-streams, Macroeconomics and Microeconomics. Macroeconomics deals with issues that affect the entire population as a whole, such as inflation, interest rates, unemployment and Gross Domestic Product (GDP), things we read in pink newspapers. Microeconomics deals with issues of individuals and firms and its main intention is to make the best possible use of available resources. This course deals with Microeconomic concepts as relevant for managers. With this background in mind, it will be apt to start with our course material. Back to Managerial Economics A key and a common problem that managers face are making the most efficient use of available resources. It should be noted that the term ‘Management’ is not restricted only to professional managers working in offices, but has various applications. For example, students face a management problem on how to make the best possible use of their available time to maximize their grades, housewives face a management problem on what resources to use to cook, clean, and do other household chores to maximize satisfaction of the household. Let us elaborate on the example of a student’s problem on how to allocate their time to various subjects to maximize their total score. Let’s assume students can predict the marks they will get for every hour they decide to study. Let us also assume a student has decided on the total number of hours he wishes to study and let that be three hours. The marks he can get for any number of hours put in for a subject is given by Table 1.1. The objective of the student is to maximize the total marks within the three hours studied. If a layman were to solve this problem, they would approach the following problem in this manner; look at all possible combinations (x, y) in which one can allocate time between English and Economics, where x denotes the number of hours devoted to English, y denotes the number of hours devoted to Economics, and look at the total score for each combination, and the combination that yields the maximum score. Therefore, the total score obtained for each of the combinations (3, 0), (2, 1), (1, 2) and Managerial Economics Page 2 (0, 3) are 70, 90, 90 and 60 respectively. Therefore, the student would choose to either study 2 hours of English and 1 hour of Economics or 1 hour of English and 2 hours of Economics. Table 1.1: Number of hours studied and marks obtained Hours of study/subjects 0 1 2 3 English 0 40 60 70 Economics 0 30 50 60 Now let’s examine how an Economist would approach the same problem. If a student decides to study for just one hour, they should allocate that study hour to English rather than Economics and get 40 marks. If they were to study for a second hour, that would go to Economics rather than English, since the increase in total marks would be 30 rather than 20, and the final score would be 70. As for the third hour, it does not matter whether one studies English or Economics, the increase in marks would be by 20, and the total score would be 90. Table 1.2: Number of hours studied and marks obtained An Economist’s View Hours of study/subjects 1 2 3 English 20 50 85 Economics 10 25 45 Now let us look at Table 1.2. If a student studies for 3 hours only, it is obvious that they should devote all that time to English. Can you comment on the difference between Tables 1 and 2, and thereby the difference in allocation that results? Remember velocity and acceleration from school days: marks in Table 1 are increasing at a decreasing rate, while those in Table 2 are increasing at an increasing rate. For that reason, a student chooses to study both English and Economics for the situation in Table 1, and chooses to study only English for the situation in Table 2. In Mathematics, we call the first an interior solution, and the second a corner solution. One can think of another example where a similar situation happens. People in general feel most happy when they receive the first unit of any good; the next unit makes them happy but not as much as the first unit did. Economists call this property the law of diminishing marginal utility, and due to this reason, we spend our money on all goods be it food, clothing or shelter. However, if a man is interested in only two goods; alcohol and cigarettes, for both goods, happiness increases at an increasing rate for every additional unit of Managerial Economics Page 3 consumption, we would then find that they will choose to spend their money either completely on alcohol or completely on cigarettes. The example above is of a situation where there is scarcity of time. Usually when we think of scarcity, we think of scarcity of resources and money. Economist Senthil Mullainathan and Psychologist Eldar Shafir wrote a book titled, “Scarcity: Why having too little means so much”, which discusses how to handle scarcity of time and scarcity of money. The fact is that having enough resources or money does not always solve all problems, though it makes life a lot easier. Retailers frequently complain about scarcity of space in stocking up things, so therefore they must make the best use of limited space and stock up wisely. Even households may have the means to buy expensive curio items to display in the house, but may choose not to buy it because of lack of space. Let us consider a simple retail store say Shaligram, the campus store at XLRI’s problem. The store has has just enough space to keep 12 cartons of goods, each carton of the same volume. Let us suppose, Mr. Agarwal, the store owner of Shaligram is required to pay all that he earns from the proceeds of the sale from the cartons to the respective wholesaler. The amount Mr. Agarwal is paid a commission per carton and the total demand for the item is given in Table 1.3, How many cartons of each should Mr. Agarwal have in his store? Table 1.3: Commission from Different Cartons No. 1 2 3 4 Items Sugar Lays Chips Parle Buscuits Old Spice Aftershave Managerial Economics Commission 100 750 400 2100 Demand Per Month 10 8 3 2 Page 4 We can see in this case, that given that there is no monetary investment involved on the part of Mr. Agarwal, he should opt for cartons that give the maximum commission. That way 2 cartons of Old Spice Aftershave, 8 cartons of lays chips and 2 cartons of Parle buscuits, earning a profit of Rs. 11000. Now let us assume in addition to the space constraint, Mr Agarwal also has a cash constraint of Rs. 10000, with which he has to buy the cartons and then sell it at a profit. The amount he has to pay per carton, the net profit/commission earned per carton, and the total demand per item is given in Table 1.4. The commission earned is the same as before. We now have to answer the same question again. How many cartons of each should Mr. Agarwal have in his store? Table 1.3: Commission from Different Cartons No. 1 2 3 4 Items Sugar Lays Chips Parle Buscuits Old Spice Aftershave Cost per Carton 1000 3000 1000 7000 Net Profit/Commission per carton 100 750 400 2100 Demand Rate Per ofReturn Month (%) 10 10 25 8 40 3 30 2 Total Money Available: Rs. 10000 We immediately notice that it is not possible to do the same level of stocking as before. If we proceed the same way as before, and stock first Old Spice, we earn Rs. 2100 of commission/profit, but exhaust Rs. 7000 of cash. It is not possible to buy the second carton of old spice. With the remaining Rs. 3000, we can buy the next best, that was Lay’s chips giving us Rs. 750 of commission. We would now earn a profit of just Rs. 2850, and space for 10 cartons will be left empty due to a cash constraint. Is there a better way of stocking up, so that we earn a higher level of profit? Yes, let us compute the return on money as done in Table 1.4 from buying each carton and then decide which one to stock first. In this case we can see that Parle biscuits give the maximum return. On stocking 3 cartons of Parle biscuits, the extra storage space is 9 cartons, however, the remaining income is INR 7000. Since, Old Spice provides the maximum return after Parle, and costs INR 7000 for one carton. Thus, the store owner stocks one carton of old spice, thereby exhausting his income with extra remaining space for 8 cartons. However, this bundle maximizes his profits of INR 3300.We can see that this is definitely an improvement over the earlier figure of Rs. 2850. Sometimes, having more than one resource is an advantage as it may be possible to substitute one for the other. For example, if you have a deadline to reach a place for an event that is important to you, if you find that it may not be possible to reach on time by train, you may choose to fly if you have enough money. In this case, time and money are substitutes. However, that is not always the case; you may need both to achieve an outcome. For example, suppose you decide to join a coaching class to ace a Management entrance examination, you are Managerial Economics Page 5 investing both time and money. Unlike in the example discussed earlier, there is no guarantee that you will ace the exam if you take the course, but the chances of doing well increases significantly. So, in the real world, we have to take decisions in an uncertain environment, which is challenging, unlike in the examples we just discussed, where it is possible to come up with the absolute right answer with some effort. Space has also been visualized from a different aspect by early economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo. Land was recognized as an important resource for production along with labour and capital. Over time the constraint ceased; with improvement in agricultural productivity, more food could be produced on the same tract of land, and with sky-scrapers, more people could live and work at the same place. Improvements in transport and the Internet made things even better. However, an article in the weekly Economist reports how space is again becoming a constraint due to urban regulations on height and density, although there are equally convincing arguments for such regulations to prevent over-crowding of a city2. In this course, we will cover the following topics: • Decision Making in the Household • Decision Making in an Enterprise • Markets: Perfect Competition, Monopoly and Oligopoly • Market Failure: Externalities and Public Goods • The Economics of Information Decisions within the household are easy to conceptualize. A household consisting of a husband, wife and children has to decide whether both spouses should be working or not. If both work, the household receives more material benefits and can enjoy a higher standard of living, but on the flip side, outside help will be required for cooking, cleaning, and looking after the children. Furthermore, a household needs to make financial decisions, such as how much to spend on goods and services monthly and how much to save for future contingencies. Of the amount that is going to be spent, what are the goods and services that the household needs to buy. A lot of these decisions depend on the household’s tastes, its monthly income, and the prices of different goods and services. All these aspects will be looked at while we discuss the topic Decision Making in the Household. The goods and services that households wish to buy are provided by enterprises. What is the incentive of these firms to provide services? It is Profits. Firms are greedy to earn more and more profits. They can do so by choosing the right technology. The best technology may not be the appropriate one; it may be too expensive and might reduce profits. Should one use laborintensive techniques or capital-intensive techniques, or a mix of both? These aspects will be examined while discussing Decision Making in an Enterprise. 2 Look up http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21647622-land-centre-pre-industrial-economy-has-returnedconstraint-growth Managerial Economics Page 6 We are all aware that profits consist of revenues minus the costs. Output prices have a large impact on deciding revenues, and input prices play a significant role in costs. Do firms have control over output and input prices? It depends on the kind of Markets we have. If there is a single firm in the market and many consumers, the firm has the entire bargaining power over prices, and can charge a very high price to maximize profits, and we have a Monopolistic market. However, if there are many firms and many consumers, no single firm or consumer has control over the price that is going to prevail and we have a Perfectly Competitive market. A firm in a perfectly competitive market cannot charge a price higher than the others – since the output sold by them is identical to what others sell, they will lose customers to others. Given the large number of firms that exist in the market, it is physically impossible for firms to collude and set a high price and earn profits. The same is however possible if there are just a few producers, say two to four firms in the market, and such markets are described as Oligopolistic markets. Strategic issues become very important in oligopolistic markets. Should firms collude amongst themselves or compete? Do producers have any strategies to deter entry? How rivals react to what a firm does are aspects a firm needs to consider while making a decision. For example, the petroleum market is an oligopolistic market. Countries forming the Oil and Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) had decided to impose quotas on the amount of oil each country could drill out, in order to limit the world supply of oil and keep oil prices high. It worked for some time, but then every country thought of drilling a little more oil and earning a bit more profit. Because each country thought in the same fashion, soon the world supply of oil became too large and global petroleum prices fell, and each country was worse off than it would have been if each had stuck to the agreement. These issues along with how firms decide how much to produce and what prices to charge in each market structure will be discussed in the Markets: Perfect Competition, Monopoly and Oligopoly section. Markets do not always function correctly. Some imperfections caused by externalities and other provisions cause market failure. The topic on Market Failure: Externalities and Public Goods discusses such issues. There are instances where we cannot rely on markets to provide certain goods and services and government intervention may be required. Public goods are defined as goods that are (a) non-excludable and (b) non rivalrous. The major reason for government intervention is for the provision of public goods like defense and foreign affairs which are non excludable and non rival in consumption. If left to the market, there will be a gross under-provisioning of such goods. Think of a residential building, where a bulb has to be put in the passage; a bulb costs Rs.20 and any resident is only willing to pay Rs.15 to light up the staircase. Even if there are two such residents, it is clear that there is a case for lighting up the staircase, but one needs some other institutional mechanism to do it. One option is for the government to collect taxes and provide for such a service. In this situation, if an individual buys a bulb and thus provides himself/herself with the service of a lit-up staircase, they indirectly provide it to others also. This is a situation of externalities where an individual’s action has an impact on others too. Since others also get the benefit of a lit-up staircase without paying a penny, they will wait for someone else to do the purchase, and this is a classic case of free riding. Therefore, in the presence of externalities, public or government intervention may be required. Benefits from Managerial Economics Page 7 consumption of private goods like food and clothing is not passed on to others who do not pay for it. In contrast, the consumption of public goods like defence is not limited only to people who pay taxes. Moreover, one person’s consumption does not decrease or limit the amount by which another person can consume. Externalities are not always of a positive variety as the one just discussed. For example, a factory letting its waste onto a river causes damage to the fisherman as their catch decreases.. Can you think of ways to solve such externality problem? One may bring both the businesses of the factory and fishing under the same ownership, or bring both parties affected by the activity to a negotiating table (Ronald Coase’s solution), or impose taxes or subsidies to discourage or encourage an activity (Pigou’s solution). Certain other goods which are supplied by the government have no characteristics of a standard public good. These goods are termed as ‘merit goods’. Examples of merit goods are education, and health. Such goods, if left for provision by the private sector might not be consumed in adequate quantities due to pricing issues. The view that the government should intervene because it knows what is in the best interest of individuals better than they themselves is referred to as paternalism. Contrary to the popular view, competition is not always desirable in society. In many industries, production is subject to decreasing average costs, and thus a single producer can produce and serve the entire market. Table 1.3 Cost structure of different industries based on number of units produced Quantity Produced 1 2 3 Industry A 2 5 9 Industry B 4 7 9 Let us look at a scenario show in Table 1.3. For an industry such as Industry A, as output increases, costs to produce the output increases proportionately. For the first extra unit, the additional cost is 3 (from 2 to 5), and for the second extra unit, the additional cost is 4 (from 5 to 9). However, for industries such as Industry B, the costs to produce additional outputs decrease. It is then economical for one firm to produce all three quantities of the good at 6 units of cost. In firms where the marginal productivity of labour or capital decreases as output increases, the cost to produce those outputs increase. For firms that have a high fixed cost to produce the first output, but minimal marginal costs for the next few quantities produced, it is beneficial that one firm produces the entire quantity. For example, if to produce one unit of good A, the cost incurred is 100, but for the second unit it is 2, then the average cost of producing two units is 51. If two firms had to produce one unit each, the total average cost would be 100. However, in such a case, the monopolist charges a higher price and limits quantities (this shall be covered in detail later in the course). It is thus imperative that the government steps in and charges a price that just covers up the cost, so that it is accessible to all sections. This was the Managerial Economics Page 8 reason why in post independent India, sectors like steel, railways and electricity were managed by the public sector. Another reason for the entry of the government is the ‘universal service obligation’ (USO). USO entails three basic fundamentals: availability of resources, affordability of resources, and accessibility of resources. There are a lot of benefits with the government providing services to the economy. However, a fully government run system has its own downfalls. Some of the major reasons why there exists a high level of inefficiency with the government are: low productivity, excessive public debt burden, lack of managerial skills, and other such factors. It is in this context that privatization helps. A perfect example of this is the opening up of the Indian economy in 1991, and allowing foreign direct investment. This measure had a lot of positive outcomes such as boosting economic growth, increasing employment and productivity and even a stronger currency. Two reasons why the private sector works well is: incentives (wages are competitive), and monitoring (which induces employees to put in the best effort). However, privatization of services can again lead to problems such as inadequate service provision, and high prices (the case of monopoly). To mitigate such concerns, regulatory authorities should impose some regulations to such industries to provide checks and balances. Till now we had assumed that both the firms and the consumers had absolutely the same idea about the product or service. This however may be true only in a few cases; for example, for perishable commodities like vegetable or fish, one can ascertain the quality and bargain on a just price. However, in many situations, firms have a better idea about product quality than consumers. Think of a situation where a person wants to sell a second-hand car, the seller definitely knows the state of the car better than the buyer. George Akerlof in a paper titled, “The market for ’lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism” first demonstrated that there may not exist a market for second hand cars. If people could decipher the quality of the car, there could be an agreement of the price that would be paid. In the absence of ways to decipher quality, the price of a used car would be that of the average quality of a used car. If that be the case, only persons with less than average quality will offer their cars for sale, and buyers knowing the same will not opt to buy. Thus, there will not be a market for second hand cars although buyers may be willing to pay more than sellers for any quality type. Such aspects about asymmetry of information between the players in the market will be discussed in the section on The Economics of Information. The problem that we just discussed is termed as adverse selection; that is, in the absence of proper information; the worst of the used cars come into the market. Now, let us take another example: the Government of India while deciding to implement the Fifth Pay Commission in the late 1990’s recommended higher pay for its employees, but felt that staff strength was too large and needed to be trimmed down, so they came up with the concept of a “leaner, meaner bureaucracy”. The way to achieve the same was thought to be by a Voluntary Retirement Scheme (VRS). Initially the VRS was open to all, and can you guess the kind of staff that opted for VRS? It was the better ones who left since they were confident of getting a job in the outside market as well as availing the VRS package. Therefore, the government faced the problem of adverse selection, Managerial Economics Page 9 that is, by offering the VRS package, they retained the worst of the lot, and therefore the “adverse selection”3. The problem of adverse selection is also much talked of in the insurance markets. If companies were not allowed access to medical records of patients, and if there existed competition in the insurance markets, the premium that people would have to pay would reflect that to be paid by the average customer. At such a premium, only people with below average health would opt for insurance and the health insurance market will fail to survive. There is another interesting problem that emerges if insurance companies were to offer full coverage for a car or a house. Given that one is fully insured against any damage, people may choose to become “careless” rather than being “careful”. Individuals may choose to drive recklessly and not bother to lock their house in case they have bought insurance with full coverage. This is termed as the problem of moral hazard, that is, if insurance companies are unable to observe the behaviour of customers, they might end up inadvertently propagating the wrong behaviour. In order to prevent such a problem, the trick is always to offer part rather than full insurance. Problems of moral hazard are also encountered in interactions between an employer and an employee. Before we start the discussion, let us be clear on the fact that most outcomes in social sciences are not deterministic like that in physical sciences. For example, sales by an employee cannot be exactly mapped to the number of hours he/she put in. A lot depends on whether it is a boom or slump period. Even with very little effort, one can get good outcome if one is lucky, and face a bad outcome despite the best of efforts. Nevertheless, higher effort reduces the possibility of a bad outcome and employers realize this and design their wage contracts accordingly. If an employee is offered fixed wages, he/she will choose to shirk and not work. Recognizing this problem, an employer may be forced to appoint monitors to monitor employees, which adds to costs. In doing so, another problem arises – how does an employer ensure that the monitor does not shirk his/her work? Think about it. An alternative would be to design a wage structure with a fixed component, and a bonus component, which is conditional on outcome. Things to decide in this case are: How much should the fixed component be? How should targets be set to receive the bonus? How high should the bonus be? If the fixed component is too low, it will be hard to find employees, so it should be high enough to induce people to work for you. The performance benchmark and the bonus are designed to induce high rather than low effort. If the benchmark is set too low, people will choose to shirk since they will get the bonus anyway. If it is set too high, most people find it difficult to achieve and may not even try to work towards it, so it is counterproductive. As far as the magnitude of the bonus is concerned, it should be just high enough to ensure that individuals put in high rather than low effort in the presence of the bonus package. Now that we have had a fair idea of the course outline, let us first brush up on a few concepts that will be needed in one or more topics. They are In fact, State Bank of India realizing this stopped the “voluntary retirement scheme” during the start of its transformation process (ref: page 62, of “Grits, Guts and Gumption: Driving Change in a State Owned Giant” by Rajesh Chakrabarti, Penguin 2010. 3 Managerial Economics Page 10 Some elementary mathematics The concept of efficiency in Economics The concept of opportunity cost Managerial Economics Page 11 Appendix 1: Some Elementary Mathematics In Economics, we deal a lot with graphs. Graphs help to conceptualize some things better. Let us again begin with a table of marks obtained for the number of hours study. Consider the data in Table 1.1. The same information can be put in a graph as seen in Figure 1. If you notice Figure 1, Hours of study 0 1 2 3 Economics 0 50 75 80 Marks in Econmics Figure 1 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 1 2 3 4 Hours of study You will see you will notice kinks occur at points 1 and 2 hours of study. A graph with such kinks is not differentiable as Mathematicians would say. What would make the above graphs smoother? If the same data of marks were available in minutes or preferably seconds rather than after each hour, we would expect the graph to look like that in Figure 2. If we had data in minutes the above graph would be smooth. If yincreases as x increases Managerial Economics dy >0 dx Page 12 Ma rks in Eco no mic s Hours of study Marks in Economics Marks in Economics Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 dy > 0, but the curves look different. Why? dx d2y d2y If at any point on the curve, if >0, the curve is locally convex, if <0, the curve is dx 2 dx 2 locally concave. In both these graphs Managerial Economics Page 13 Concave Convex y y x Figure 5 x Figure 6 If the chord joining any two points on the curve lies below the curve, it is globally concave, if it lies above the curve, it is globally convex. y y x Figure 7 Comment on x d2y dy and dx dx 2 Managerial Economics for these two curves. Are these curves convex or concave? Page 14 y y x Figure 9 dy Comment on dx x Figure 10 d2y and for these two curves. Are these curves convex or dx 2 concave? Managerial Economics Page 15 Appendix 2: The Concept of Efficiency in Economics Most organizations are concerned about whether they are being run efficiently. Efficiency would imply the best possible use of available resources, and it is a relative concept. Relative in the sense that for a particular score, we mark out who performs best, give that entity the full score, and other entities are marked as inefficient and the extent of inefficiency is measured by the extent to which it falls short relative to the one that performs best. In Economics, discussions around efficiency centre on mainly two concepts, namely: Productive or Technical efficiency Allocative efficiency Productive efficiency is easy to conceptualize if there is a single input being used for the production of a single output. In such a situation, the technology that uses the least input to produce a unit of output is the most efficient. Inefficiency of others must be measured relative to this most efficient technology. However, if two or more inputs are being used to produce a single output; or a single input being used to produce two outputs, more than one production technology may be efficient. The concept of efficiency we would now introduce is attributed to Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923)4. An economy will be said to have achieved technical efficiency, if given the inputs available, two products X and Y are being produced; it is not possible to increase the production of X, without sacrificing the production of Y. That is if 5 units of food and 2 units of clothing is currently being produced, increasing food production to 6 units may imply reducing clothing production to 1 unit. In both situations then the economy is efficient, however if the same economy produces 2 units of food and 1 unit of clothing, it is definitely inefficient. Outputs X and Y will finally be consumed by different households. If it is not possible to redistribute X and Y amongst households such that a household can be made better off only by making some household worse off, then we have achieved allocative efficiency.Distribution of goods and services amongst individuals may be efficient, but not equitable, and vice versa. For example, let an economy produce 1000 units each of both X and Y, and let there be 100 individuals. An allocation of 10 units each of X and Y is an equitable allocation, but not necessarily efficient. Of the 100 individuals, let there be one who prefers more X to Y and another who prefers more Y to X. These two individuals can exchange X and Y amongst themselves, and after the exchange we have 98 individuals who are as well off as before, and these two individuals better off, so the initial allocation of 10 units each of X and Y to each individual was surely not efficient. Pareto went on to prove that if all markets (markets such as food and clothing) were competitive, we would arrive at a set of prices in each market at which • All producers maximize their profits Look up The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics for more information about Vilfredo Pareto’s academic contributions. 4 Managerial Economics Page 16 • All consumers maximize their welfare subject to a budget constraint • Demand equals supply in all markets5. The immediate implication of this theorem is that it is desirable to have competition in each and every market. This is something that we investigate further in this course. 5 Refer to Hal Varian, Intermediate Economics, chapter 31, for a formal mathematical proof of the same, if interested. Managerial Economics Page 17 Appendix 3: The Concept of Opportunity Cost in Economics In Economics, we not only use the concept of absolute costs of production in the sense of the amount of resources used to produce a certain good, but also another concept of opportunity cost. Since resources are limited, the same may be used for the production of one or some other good. While investing in any line of production, businesses have to evaluate the profits that would be available here to the profits available in the next best alternative. For example, the opportunity cost of studying for an MBA in XLRI is not just the tuition costs, but must also include the amount one would have earned by working with the current qualification and experience. David Ricardo (1772-1823) used the concept of opportunity cost to demonstrate that trade can benefit both countries. He showed that with specialization, countries can manage to make the size of the cake bigger, and thus both can be better off, than in a situation where countries produce all by themselves and neither export nor import. Before we introduce his theory, let us first discuss the idea of a Production Possibilities Frontier. The Production Possibilities Frontier is a graph that shows the various combinations of output, such as food and clothing, that an economy can produce with the given resources and the available technology. Clothing Figure 11 4 2 Food For example, in Figure 11, with the available labour resources, an economy can produce either 4 units of clothing or 2 units of food, or some combination of the two. The slope of the line gives us the opportunity cost of producing food. That is, the opportunity cost of producing food in this economy is 2 units of clothing; that is, this society has to sacrifice 2 units of clothing in order to consume a unit of food. Now let us look at another example in Table 1.2, the production possibility frontier for this technology is given in Figure 12. As we can see, the graph is convex; output is increasing at an increasing rate. Managerial Economics Page 18 Table 1.2 Hours 1 2 Food 2 5 Clothing 2 5 Cl ot hi ng Figure 12 5 5 Food Now let us consider another example in Table 1.3. The production possibility frontier for this technology is given in Figure 13. It is concave since production is increasing at a decreasing rate. Table 1.3 Hours 1 2 Food 2 3 Clothing 2 3 Managerial Economics Page 19 Cl oth ing Figure 13 Food Let us now define the concept of absolute advantage. Let us now assume that there exist two countries A and B, each with two units of labour given in Table 1.4 and 1.5 respectively. A Table 1.4 Hours 1 2 Food 1 2 clothing 2 4 Hours 1 2 Food 2 4 clothing 1 2 Table 1.5 B With 2 units of labour, country A can produce 2 units of food, while country B can produce 4 units of food. So, country B has an absolute advantage in food production, if it uses fewer resources to produce one unit of food. Likewise, country A has an absolute advantage in the production of clothing. With the same example, let us now bring in the concept of comparative advantage. The opportunity cost of producing food is 2 units of clothing for A and ½ unit of clothing for B. B has a lower opportunity cost of producing food, so it has a comparative advantage in the production of food. Likewise, country A has a comparative advantage in the production of clothing. Does absolute advantage in the production of a commodity imply Managerial Economics Page 20 comparative advantage in the production of the same commodity? Not necessarily; the next example will illustrate the same. In the next example, the production technology of country A is given in Table 1.6 and of B in Table 1.7. Table 1.6 Hours 1 2 3 Food 1 2 3 clothing 1 2 3 Table 1.7 Hours 1 2 Food 2 4 clothing 6 12 Country B has absolute advantage in the production of both food and clothing. The opportunity cost of producing food is 1 units of clothing for A and 3 unit of clothing for B. Therefore, country A has a comparative advantage in the production of food. By similar reasoning, country B has a comparative advantage in the production of clothing. Country A has 3 units of labour and country B has 2 units of labour. Before trade, A produces 1 unit of food and 2 units of clothing, while B produces 2 units of food and 6 units of clothing. Both countries together produce 3 units of food and 8 units of clothing. Countries should specialize in the commodity where they have a comparative advantage. Therefore, country A should specialize in and produce 3 units of food and B should specialize in and produce 12 units of clothing. With specialization, the total production of food is 3 units the same as before trade, but that of clothing is 12 units higher than before trade, by 4 units. Now if there is going to be trade, what should the exchange rate be between food and clothing? How many units of clothing should be exchanged for a unit of food? For both countries to benefit from trade, the exchange rate should lie between the opportunity costs for producing food for both countries. The opportunity cost of producing food is 1 unit of clothing for country A and 3 units of clothing for country B. Let the exchange rate be 1 unit of food exchange for 2 units of clothing. Managerial Economics Page 21 In the situation after trade, at the exchange rate of 1 unit of food for 2 units of clothing, country A can give up 2 units of food and get 4 units of clothing. So, it consumes (3-2)= 1 unit of food and 4 units of clothing after trade.It consumes 2 units more of clothing after trade,so it is better off. After trade, country B gets 2 units of food and (12-4) = 8 units of clothing. It is better off in a situation after trade by 2 units of clothing. Therefore, trade makes both countries better off. It should be noted that if the exchange rate is close to 1, all the gains from trade accrue to country B; if the exchange rate is close to 3, all the gains from trade accrue to country A. As to where the exchange rate would settle, depends on the bargaining powers of country A and country B. Very often countries do not deny the gains from trade, but are in conflict as to how the gains from trade are to be shared. As to what the exchange rate between commodities should be is often termed as “terms of trade”. The concept of ‘comparative advantage’ among nations is also linked to the global economic history of industrialisation in the West. In the book ‘Global Economic History: Short Introduction’, the author explains how The Industrial Revolution in the West drove Asian manufacturers out of business for two reasons: Productivity in manufacturing, lower transportation costs. Manufacturing became more productive in Europe, cutting costs there. Industrial technology, however, was not cost-effective in other parts of the world where wages were lower. There was no point, for instance, in the Indians trying to compete against English textiles by using spinning machines since they increased the capital costs of spinning in India more than they lowered the labour costs. Asian producers either had to hope that the British would improve spinning machines sufficiently to make them cost-effective in Asia (which eventually did happen) or redesign the machines to adapt them to their own circumstances (which is what Japan did). Suppose India, for instance, were cut off from the rest of the world. The only way to increase its consumption of cotton cloth would be by reducing employment in farming and shifting the workers to spinning and weaving. The efficiency of labour in these activities would determine how much wheat had to be given up to get another metre of cloth. If it became possible to trade internationally, and if the price of cloth relative to wheat in the world market was less than the ratio implied by domestic production techniques, then Indians would have found it advantageous to export wheat and import cloth rather than producing the cloth themselves. They would, in other words, have become farmers rather than manufacturers. This reconfiguration brought short-run prosperity at the cost of long-run development. Managerial Economics Page 22 The impact of comparative advantage on the cotton industry in India The productivity of cotton rose in Britain while it fell in India. Conversely, India’s comparative advantage in the production of agricultural goods should have increased, while England’s declined. Comparative advantage implies that the unbalanced productivity growth of the Industrial Revolution should have furthered industrial development in England, while de-industrializing India. And that is what happened. The effect of unbalanced productivity growth and declining shipping costs shows up in the histories of cotton prices in England and India. In 1812, a group of English cotton manufacturers met to oppose the extension of the East India Company’s trade monopoly. They prepared a memorandum that showed 40-count yarn cost 43 pence per pound to spin in India but only 30 pence in England. The conclusion was that India was a great potential market for British products if only competition were allowed. Every country has a comparative advantage in something. As India lost its advantage in manufacturing, it gained an advantage in agriculture – raw cotton, in particular. Economists are however seriously divided on the issue of whether trade benefits all countries. Joseph Stiglitz, the 2001 Nobel Prize winner, in his book titled “Globalization and its Discontents” outlines the perils of globalization. In response to that book, a famous Indian Economist, Jagdish Bhagwati based in Columbia University wrote a book titled “In Defence of Globalization”. In one of the most comprehensive books on the welfare and ill effects of Globalization, Dani Rodrick’s book, “The Globalization Paradox” gives instances where trade between nations could have been viewed as unfair. Way back when the Hudson Bay company started trading with the American Indians in exchange for blankets, kettles, rifles and brandy, there were charges by opponents that they were underpaying American Indians for beaver furs and charging high prices for English goods. The Hudson Bay Company justified the prices as fair given the difficulty of trade in the American wilds. In short, since they were the only trading partner to the American Indians, they could afford to do so. Different interest groups gain or lose with free trade. In particular, within domestic markets, if a country is a net importer of a good, consumers gain and producers lose and vice versa. In 2012, the Indian government put a cap on exports on cotton yarn in order to help the textile Managerial Economics Page 23 industry keep cotton fabric prices low. However, this cap greatly hurt the cotton farmers who were any way going through a rough patch due to inadequate rainfall6. Coming back to the applications of opportunity cost, the Ricardian model of trade need not only apply to trade between countries, it may also apply to earning and sharing of housework between spouses and many other circumstances. Try to apply the Ricardian model to another example or critique as to why things will not work as Ricardo suggested. 6 Look up http://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/features/cotton-supply-chain-linkstruggling/story/23563.html for more details on this story. Managerial Economics Page 24