Mary Bateman, 'A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey'

advertisement

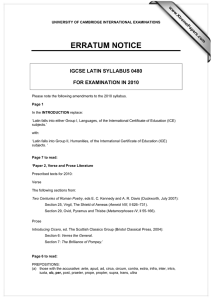

Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) A Newly-Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey Abstract This article provides the first detailed study of a manuscript held in the archives of Downside Abbey in Stratton-on-the-Fosse, Somerset, UK. The manuscript, Downside 78291 (henceforth F), contains a Latin prose chronicle which has not previously been described or identified. The present article demonstrates that it is a copy of the chronicle known as the Latin Prose Brut. After a codicological and paleographical study of the manuscript itself, I contextualise this witness within the wider Latin Prose Brut tradition, and suggest a possible author: William Worcester. Textual variants in this copy of the Brut evince a pro-Lancastrian bias common to many Latin Prose Bruts of the fifteenth century; but there is also evidence of an author keen to emphasise England’s historic victories against France. Keywords Codicology, Downside, history, palaeography, manuscripts, medieval, pro-Lancastrian, AngloFrench relations, Prose Brut Introduction The present article concerns a manuscript that was recently discovered in the Library and Archive at Downside Abbey in Stratton-on-the-Fosse, Somerset. The discovery was made as part of an ongoing cataloguing project lead by George Ferzoco.1 The manuscript has not previously been described. It forms part of the collection bequeathed to the library by Downside School alumnus and prolific manuscript collector David Rogers after his death in 1995. 2 It was therefore not at Downside when Ker visited during his major cataloguing project, though it appears in Ker’s addenda published in 2002. 3 It contains a chronicle of England (the spine of the binding reads ‘MS Chron. Anglie’, and [p. 167] Ker lists it as Chronicon Anglie). It is written in Latin prose, and has hitherto not been correctly identified. On the opening folio, an early modern reader – probably Thomas Martin (see below) – writes: ‘this seems to me to be either a copy of Gildas, continued by some writer to his own Days, or else an entire work of his, in which he makes much use of Gildas’ (f. 1r). In fact, the manuscript is a copy of a text known as the Latin Prose Brut, a chronicle of the British and English kings that begins with Brutus. As I hope to show, the text bears a close resemblance to another copy of the Latin Prose Brut, Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 311, but before discussing the affiliations of this chronicle with the complex Stratton-on-the-Fosse, Somerset, Downside Abbey 78291 (F). I extend my gratitude to George Ferzoco for making me aware of the manuscript, and for offering his support and advice in the writing of this article. 2 Bent Juei-Jensen, ‘Obituaries: David Rogers’, The Independent, 9 June 1995 <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituaries-david-rogers-1585536.html> [accessed 3 May 2019] 3 Downside Abbey 78291 (no. 147) in N. R. Ker, Addenda to Medieval Manuscripts in British Libraries, 5 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969-2002), V (2002), p. 10. For Ker’s catalogue of the entire Downside collection, see Ker, Medieval Manuscripts, II, pp. 419-477. 1 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) Latin Prose Brut tradition an examination of the manuscript is in order. The following sigla gives the abbreviations that this article uses for each manuscript:4 L = London, British Library MS Lansdowne 212 B = Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson B. 169 H = London, British Library MS Harley 3884 J = Oxford, St John’s College MS 78 E = Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 311 G = Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College MS 72/39 F = Downside 78291 The Manuscript Manuscript Stratton-on-the-Fosse, Downside Abbey 78291 is a paper manuscript of 91 folios measuring 144mm x 220mm. It contains only one text: the Latin Prose Brut. The manuscript appears to be the work of a single scribe, although some pages are more cramped than others, which suggests that this may have been a personal copy. The script, written in black ink with red rubrication and initials, is a medium-grade anglicana hand with secretary features (such as the flat-top secretary g). The script appears to date from the second half of the fifteenth century, and the paper stock used throughout bears a 1460 watermark from Bordeaux – a front-facing bull with a tripart tail – meaning that the manuscript must have been composed after 1460. 5 The early modern binding is later – perhaps eighteenth century. Early modern marginalia is present throughout, some of which reveals information about the manuscript’s ownership history. Somebody – probably David Rogers, given the appearance of similar additions made to other Downside manuscripts that he is known to have acquired – has also added pencil notes on the manuscript’s provenance to a flyleaf. The manuscript’s previous owners, in reverse chronological order, are identified as John Borthwick of Crookston (1787-1845); ‘honest Thomas Martin of Palgrave’ (1697-1771); Francis Blomefield (1705-1752); and ‘Richard Benstad’. Borthwick’s bookplate is pasted to the front endpaper; and a further bookplate and marginal signatures throughout belong to Blomefield, who looks to have purchased the codex on September 17 th 1735. Martin, who would have acquired the manuscript as part of Blomefield’s collection, leaves his signature on the front endpaper. After Martin’s death, his collections were broken down and sold through [p. 168] various channels; several catalogues from these sales survive, one of which contains a listing that may be the Downside Codex.6 The earliest owner or reader was ‘Richard I follow Kingsford’s manuscript abbreviations here with the addition of G and F. I have been able to inspect all of these manuscripts excepting J. 5 C. M. Briquet, Les filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600 avec 39 figures dans le texte et 16 1123 fac-similés de filigranes, 4 vols (Geneva: A. Jullien, 1907), I, no. 2785. 6 There were several catalogues made of Martin’s partial collections: one printed in Lynn, A Catalogue of the Library of Mr. Thomas Martin, of Palsgrave, in Suffolk, deceased (Lynn: W. Whittingham, 1772), ESTC T98426; a sales catalogue for Booth & Berry, Norwich Bibliotheca Martiniana: A Catalogue of the entire Library of the late 4 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) Benstad’, whose autograph, a seventeenth-century hand, appears throughout the codex (ff. 1r, 13r, 20v-21r, 56v, 70v-71r). The same hand also writes the names ‘Thomas’ (f. 1r), ‘T. C. Eng Benstad’ (f. 71r), ‘Mary Alger’ (f. 56v), ‘Light’ (ff. 1r; 13r; f. 56v, f. 70v), and perhaps ‘Elizabeth Maman’ (f. 74v), and a date, ‘1696’ (f. 74v). An eighteenth-century hand – perhaps Blomefield’s – has added an informal contents page to the flyleaf, listing the English kings after William the Conqueror. The list ends with Henry V, which suggests that the chronicle’s final section on Henry VI was already absent from the manuscript by this stage (the beginning and end of the chronicle have been cut out). Structurally, the manuscript consists of eight quires, originally of twelve folios each (senions), although the third quire wants two before and after f. 25, and the seventh quire wants two before f. 71; these missing folios were excised from the codex at some point. Moreover, the final quire wants one folio at the end. At these points the text is imperfect: f. 24v ends with the death of St Oswald and the beginning of Cadwallader’s reign, and f. 25r picks up again with descriptions of the seven Anglo Saxon kingdoms, beginning with Kent.7 Folio 25v ends by introducing the third Anglo Saxon kingdom of East Anglia (‘Estanglorum’) ruled by Redwald (fl. c. 599-624), and f. 26r opens halfway through the reign of King Ine.8 Between folios 70 and 71, there is missing material concerning the end of King Henry III’s reign, the Second Barons’ War, and the beginning of Edward II’s reign.9 Moreover, the beginning and ending of the chronicle is missing. There appears to have originally been another quire containing the opening of the Brut which has since been lost: the text begins with the reign of Enniaunus (Ker misread this as ‘Ecumanus’), and the text for the preceding kings, Brutus through to Marganus, is missing. Similarly, the text ends abruptly mid-sentence during Henry V’s diplomatic negotiations with Emperor Sigismund; in E, there are a further 14 folios after this point detailing the lives of Henry V and VI, ending with the murder of James I of Scotland.10 This suggests that Downside 78291 may lack a further quire at the end of the text. eminent antiquary, Mr. Thomas Martin, of Suffolk (Norwich: Booth and Berry, 1773), ESTC T98425; and a sales catalogue for Baker and Leigh, A Catalogue of the very curious and numerous collection of MSS. Of Thomas Martin, Esq. of Suffolk, lately deceased (London: Baker and Leigh, 1773), ESTC T28840. Only the Baker and Leigh catalogue contains a listing that could match Downside 78291: a paper manuscript ‘genealogy of the Kings of England to Hen. VI, O. 16. O H’, no. 120, p. 6. 7 The end of f. 24v reads: ‘Cadwaladrus filius Cadwallonis successit patri. ¶ Cuius’; this corresponds verbatim with another Prose Latin Brut manuscript, Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 311 f. 30v. In the Downside manuscript, the opening of f. 25r reads: ‘diu imposterum tenebunt nouit ille cui nichil latet. De septem vero regnis prodans eorumque limitatibus [….]’, which corresponds with E at f. 31v. Here and elsewhere, underlined text represents expanded abbreviations. 8 The end of f. 25v reads: ‘Tercium Regnum fuit Estanglorum quod huit Reges quosdam paganos et Redwaldum qui fidem Christi susceperat sed postmodum Apostatauit. eius filius’, which corresponds with f. 32r in E; the opening of f. 26r reads: ‘domibus Regni sui beato Petro concessit quod dicia ab Anglis Romescot latine vero de narvis Petri vocabatur. […]’, which corresponds with E at f. 33r. 9 The closing passage of f. 70v reads: ‘Edwardus veniens de Wygornia viam comitus ad filium suum in Castro de Kenelworth tendentis interclusit. sic que Comes apropinquas’, which corresponds with the end of E, f. 74v. Folio 71r opens thus: ‘in quo multa ad Regis Regni que reformacionem siuit statuta ad quorum obseruacionem Rex prefato iuramento subscripsit […]’, which corresponds with E at f. 76v. 10 ‘ ¶ Interim Sigismundus et henricus Reges legates quendam Comitem Romanorum Regis . & Anglia Comitem Warwici cum plurimus sapientum’, f. 91v. This corresponds with the end of f. 94v in E. Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) The Prose Brut and the Latin Prose Brut The group of chronicles known as the Prose Brut were clearly highly popular and widely disseminated in a number of languages, and as such I will refer to both the ‘Prose Brut’ – which encompasses Prose Brut chronicles across different languages – and the ‘Latin Prose Brut ’ specifically. Discounting early print books, there are currently at least 51 known manuscripts containing the Anglo Norman Prose Brut, 183 containing the Middle English Prose Brut. There are far fewer extant witnesses of the Latin Prose Brut - between 17 and 28 copies, depending on whether one follows the classifications of Matheson, Kennedy, or Kooper.11 Distinct from the older versified Bruts of Wace (in Anglo Norman) and Laȝamon (in Middle English), the first Prose Brut was an Anglo-Norman chronicle beginning with Brutus and ending with the reign of Henry III in 1272. The oldest Anglo-Norman version, an edition of which was recently published by Julia Marvin, formed the basis for all subsequent versions and continuations of the Prose Brut.12 It should not be confused with Brut chronicles more widely, which can (confusingly) be in either verse or prose. Rather, the Prose Brut is a subgroup with its own [p. 169] specific characteristics (for example, the oldest Anglo-Norman Prose Brut uses a particular group of sources, including Gaimar’s Estoire and the Barlings chronicle).13 In sum, a ‘Brut in prose’ is not the same as the ‘Prose Brut’. The Anglo Norman Prose Brut enjoyed many reinventions and afterlives, including translations into Latin, Middle English (and back again), and other vernaculars such as Welsh The most comprehensive manuscript lists for the Anglo-Norman, English, and Latin versions can be found in Lister M. Matheson, The Prose Brut: The Development of a Middle English Chronicle, Medieval Texts & Studies 180 (Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University, 1998), pp. xvi-xxxvi. Matheson builds on the work done by C. L. Kingsford, English Historical Literature in the Fifteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon, 1913), pp. 310-12. Matheson counts 24 Latin Prose Brut witnesses; E. D. Kennedy disagrees with Matheson’s count, identifying 16 plus (later) two more: see E. D. Kennedy, ‘Glastonbury’, in The Arthur of Medieval Latin Literature, ed. by Siân Echard (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2011), pp. 110-31 (p. 119); E. D. Kennedy and Peter Larkin, ‘Prose Brut, Latin’ in The Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle, ed. by Graeme Dunphy and Cristian Bratu (Brill, online 2016) <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/22132139_emc_SIM_02111> [accessed 31 October 2019]; E. D. Kennedy, ‘“History Repeats Itself”: The Dartmouth Brut and Fifteenth-Century Historiography’, Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Cultures, 3.2 (2014), 196–214 <https://doi.org/10.1159/000075162>. A further highly unusual Latin Prose Brut was identified in 2016: see Erik Kooper ‘Longleat House MS 55: An Unacknowledged Brut Manuscript?’ in The Prose Brut and Other Late Medieval Chronicles: Books Have Their Histories, Essays in Honour of Lister M. Matheson, ed. by Jaclyn Rajsic, Erik Kooper, and Dominique Hoche (York: York Medieval Press, 2016), pp. 75-93. Although the Longleat manuscript doesn’t fit into either Matheson or Kennedy’s systems of classification, Kooper has shown that it is ultimately based on the oldest Anglo-Norman Prose Brut, and it does not resemble the ‘similar chronicles’ rejected by Kennedy. I therefore include it in my own count of Latin Prose Brut manuscripts (28, including the Downside witness). 12 Julia Marvin (ed. and trans.), The Oldest Anglo-Norman Prose Brut Chronicle: An Edition and Translation, Medieval Chronicles 4 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006). See also Ruth J. Dean and Maureen B. M. Boulton, Anglo-Norman Literature: A Guide to Texts and Manuscripts (London: Anglo Norman Text Society, 1999). 13 Julia Marvin, ‘Sources and Analogues of the Anglo-Norman Prose “Brut” Chronicle: New Findings’, Trivium, 36 (2006), 1–31. 11 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) and Middle Dutch.14 As well as translations, a number of continuations and adaptations of the Prose Brut were composed throughout the Middle Ages: the authors of these continuations may have seen their work as an act of restoration, rather than invention.15 Downside 78291 has one such continuation, and although the end of the text is cut away it is likely to be the version that finishes in 1437, ending with the murder of James I of Scotland.16 The sheer number of variations across extant Prose Brut manuscripts has led to difficulties in classifying these chronicles. C. L. Kingsford, working on the Prose Brut in the early twentieth century, appears to have found the Prose Brut’s classification a problematic exercise: he sets out myriad versions and continuations plus a number of ‘peculiar versions’.17 This outlier category was also picked up by Matheson, who proposed four Prose Brut groups (across all languages): the Common Version, the Extended version, the Abbreviated Version, and a further group of ‘Peculiar Texts and Versions’.18 There are three main reasons for these difficulties in taxonomy. Firstly, the interrelationship between the vast number of extant Prose Bruts (across all languages) is extremely complex, both codicologically speaking and in terms of textual content.19 Some Latin Prose Bruts are copied from Anglo Norman versions; others are copied from other Latin Prose Bruts; and others might be translations of the Middle English version(s). Sometimes, a Prose Brut might be a translation of a translation. What’s more, Prose Brut scribes might work from several different exemplars, perhaps even from several different languages. As Kingsford puts it: ‘the most likely solution is that the Brut was not the homogeneous work of a single writer, but that various hands were at work on it during a number of years, selecting their material sometimes from one quarter and sometimes from another.’20 Secondly, the Prose Brut appears to have been seen as a text that was perfectly suited to customisation and adaptation: filled with pseudoexplanations for toponyms, often based in legend, the Prose Brut was a text that begged to be personalised, and indeed it was. For example, MS Longleat 55, which was produced in Somerset, provides details about Glastonbury concerning Melkin’s prophecy that do not appear in other Latin Prose Bruts.21 With this in mind, Edward Donald Kennedy said that it is ‘more accurate to speak of Prose Brut chronicles rather than one chronicle, since a number of the manuscripts are textually quite different from one another with interpolations not found in others.’ 22 Erik On the Welsh Brut y Brenhinedd, see Katherine Himsworth, ‘Brut y Brenhinedd’, in Arthur in the Celtic Languages: The Arthurian Legend in Celtic Literatures, ed. by Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan and Erich Poppe (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2019), pp. 95-110. Most recently, Sjoerd Levelt has identified a Middle Dutch chronicle published in 1480 as a Prose Brut according to Kooper’s criteria (Levelt’s edition of the work is forthcoming). 15 Daniel Wakelin, Scribal Correction and Literary Craft (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 51. 16 See Matheson, pp. 44-46. 17 Kingsford, English Historical Literature in the Fifteenth Century, p. 122. 18 Matheson, The Prose Brut, ob. cit. 19 Matheson gives a synoptic inventory of the various versions of the Prose Brut in Matheson, The Prose Brut, pp. 67-78. 20 Kingsford, p. 128. 21 Kooper, p. 81, p. 84. 22 E. D. Kennedy, Chronicles and Other Historical Writings, A Manual of the Writings in Middle English, 1050-1500, 8 (New Haven CT: Archon, 1989), p. 2629. 14 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) Kooper provides the most useful advice for understanding the Prose Brut: ‘to bring more clarity to the discussion we should begin by accepting that a “Prose Brut chronicle” is a genre, not a specific text’.23 In my view, the Prose Brut seems to sit somewhere between a genre and a text, emblematic of the collaborative and often anonymous approach to writing history in the Middle Ages. The Prose Brut was a constantly evolving collaborative project, and in some English Prose Brut witnesses the text is described as ‘compilid and writen’ by ‘many diuerse good men’ rather than a single author.24 [p. 170] The Latin Prose Brut Aside from the matter of identifying the Prose Brut, there is also the question of how to identify and classify the Latin Prose Bruts as a subgroup.25 Matheson counted 24 Latin Prose Bruts.26 Kennedy, on the other hand, considers eight of Matheson’s 24 to actually represent five different chronicles.27 To these, we can add four new discoveries: Huntington MSS 48570 and 19960 respectively; MS Longleat 55; and the present Downside witness. 28 The total number is prone to variation, not only because there is no scholarly consensus on the precise parameters for defining a Latin Prose Brut but also because ‘it is almost certain that a number of texts remain unidentified in sketchily catalogued manuscripts’.29 There are a huge number of different versions, continuations, and an Albina prologue in some witnesses. Given these idiosyncrasies, present in a huge number of Latin Prose Brut manuscripts, it can be difficult to distinguish between what Kingsford and Matheson have dubbed ‘peculiar’ versions of the Latin Prose Brut (or ‘doubtful’ versions which are difficult to categorise), and other chronicles that derive from it. The demarcations that clearly separate one text from another do not exist when it comes to the Prose Brut. Matheson divides the Latin Prose Brut into three different versions: the first is a close translation of the shorter Anglo-Norman version; the second version continues to 1437 in its fullest form; and an anomalous third version, present in British Library Harley MS 941, appears to be unique.30 Kooper’s recent discovery, however (MS Longleat 55) does not fit neatly into this taxonomy. With this in mind, Kooper has put forward a useful set of criteria for identifying Latin Prose Bruts that do not fit into Matheson’s existing classification: 1. A Prose Brut must begin with an ‘account of the first settling of Britain by Brutus’ (this can also include the Albina legend or the Troy story). 2. It must also contain, at the very least, ‘a short history of both the British and the Anglo-Saxon kings’, and ‘continue after the Norman conquest at least as far as the death of Henry III or the coronation of Edward I’ [i.e., c. 1270]. Kooper, p. 77, p. 89. Glasgow University Library MS Hunter 83 f. 15r; British Library MS Harley 3730 f. 2r. Cited in Wakelin, Scribal Correction, p. 51. 25 The complexities are summarised in Matheson, pp. 37-39. 26 Matheson, pp. 37-46. 27 Kennedy, ‘Glastonbury’, p. 119. 28 See Kennedy and Larkin, ‘Prose Brut, Latin’; E. D. Kennedy, ‘“History Repeats Itself”. 29 Matheson, p. 39. 30 Matheson, pp. 37-47. 23 24 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) 3. ‘The majority of the material should be based on earlier Prose Brut texts, and thus ultimately go back to the Oldest Version of the Anglo-Norman Prose Brut ’.31 While the first and second criteria on this list are included in the broadest parameters as posited by Diana Tyson, the third point – that to be a Latin Prose Brut a text must be based on the oldest Anglo-Norman Prose Brut, which has been critically edited and studied by Julia Marvin – sets the Latin Prose Brut apart as a specific text with its own particular set of sources and characteristics. 32 Kooper’s criteria proved very useful for his purposes because MS Longleat 55 presents several unique features throughout that do not allow it to fit into either Matheson’s or Kingsford’s taxonomies, suggesting that it is either a new translation of the Prose Brut into Latin or else a version that is not included in existing classifications. However, as I will go on to demonstrate, Downside 78291 does closely resemble extant Latin Prose Brut manuscripts whose identifications have not been contested since their discovery by either Kingsford, Matheson, or Kennedy. For my purposes, therefore, Matheson’s taxonomy of the Latin Prose Brut manuscripts provides a good point of departure. The following section sets out the extant versions of Latin Prose Brut witnesses and contextualises Downside 78291 within this framework. [p. 171] Downside 78291: The Text We can now begin to compare Downside 78291 with the existing Latin Prose Brut witnesses. None of the eight witnesses representing five ‘different’ chronicles (according to Kennedy) match the text of Downside 78291, and they can be immediately disregarded. Nor does Downside correspond with MS Longleat 55. This leaves the 18 Latin Prose Bruts identified by Kennedy. These can be divided between the two major Latin Prose Brut categories theorised by Matheson. The first version ends in 1367, and appears to be a translation of the Short Version of the Anglo-Norman Brut.33 The second version of the Latin Prose Brut, in its most complete form, continues to 1437 and the murder of James I, and seems to constitute a compilation rather than a simple translation. Within this second version, Kingsford identifies two sub-categories based on their post-1399 material: one with a brief life of Henry V (known as the ‘common version’), the other with a fuller account of his reign.34 G, which had not previously been examined, contains the shorter version, and does not represent a copy of E as has previously been thought.35 The Huntington manuscripts identified by Kennedy also contain the shorter Kooper, p. 89. See Marvin (ed and trans), The Oldest Anglo-Norman Prose Brut Chronicle; Marvin, 'Sources and Analogues'. In her 1994 catalogue of Anglo-Norman Prose Brut chronicles Diana Tyson included 116 manuscripts, but as Kooper has demonstrated Tyson’s parameters are so broad that many other chronicles that are distinct from the Prose Brut could also fit into her taxonomy. See Diana Tyson, ‘Handlist of Manuscripts Containing the French Prose Brut Chronicle’, Scriptorium, 48 (1994), 333-44; and the discussion in Kooper at pp. 87-93. 33 For a description of the first version, see Matheson, pp. 39-42. Most recently, this ‘version’ has been observed to differ in terms of the extensiveness and nature of its continuations; in personal communication, Trevor Russell Smith has suggested to me that this might be considered a further Prose Brut subgroup which Russell Smith terms ‘the Canterbury Latin Prose Brut.’ 34 Kingsford, pp. 310-337. 35 G, ff. 49v-51r. M. R. James, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Gonville and Caius College, 2 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1907), 72/39, I, pp. 65-66. The misunderstanding may have come from James’ remark that ‘the same chronicle is in MS. Corp. Chr. Cant. 311’ (p. 66). 31 32 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) version of Henry V’s life.36 The version with the longer Henry V material is represented by the following manuscripts: British Library MS Lansdowne 212; Oxford, St John’s College MS 78 (J); Bodleian Rawlinson B. 169 (B), although this follows the shorter version for Henry IV; and British Library Harley 3884 (H), which continues to 1455. As well as these manuscripts, there are three other ‘peculiar’ versions that include slightly different versions of Henry V’s reign: Bodleian Rawlinson C. 234 (known previously as the ‘Godstow Chronicle’) is fuller for the years 14151421; Bodleian Rawlinson B. 147 includes the long version of Henry’s reign but with ‘distinctive peculiarities’; and Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 311 (E), which though different to the other versions (as we will discuss shortly), falls into the ‘long’ category.37 Downside 78291 belongs to the group of Latin Prose Bruts that contain the long life of Henry V. Whilst we must acknowledge that the scribe of the Downside manuscript may have worked from multiple exemplars, we can initially narrow down the witnesses with which to compare Downside 78291 based on this longer Henry V group. We can immediately disregard C. 234 (the Godstow Chronicle): neither its earlier portions nor its post-1399 material resemble the Downside manuscript. Similarly, the idiosyncrasies which Kingsford identifies in B. 147 do not appear in Downside 78291.38 This leaves five manuscripts to consider: L, H, B, J, and E. This subgroup represents the version of the Latin Prose Brut referred to in some manuscripts as the ‘new’ chronicle (‘nova’): E, for example, opens with Nova Cronica on a flyleaf (the opening of Downside has been excised but may have contained a similar title).39 This particular recension first appeared in the fifteenth century as Lancastrian propaganda (which perhaps explains its profession to be a ‘new’ chronicle).40 It was first written in Latin, and was later translated to English as the New Croniclis (Matheson’s PV-1437:B).41 As yet, the Latin Prose Brut has not been critically edited, saving Kingsford’s edition of the post-1399 material in the nine manuscripts that were then known (both the short and long versions of Henry V’s reign). Kingsford collated from L, H, B, and J, but not E – CCCC MS 311 – because E had not yet identified (G was assumed a copy). As I will demonstrate, Kingsford also missed some important variants in B, which are shared (to a greater or lesser extent) with Downside and E. In terms of the manuscripts used by [p. 172] Kingsford in his edition, Downside shares the most variants in common with J and L, although where J and L present different textual variations Downside tends to resemble J. Downside resembles B more closely still (these variants are not always recorded by Kingsford). This suggests that Downside sits closer to B in the existing stemma than the other witnesses. Kennedy and Larkin, ‘Latin Prose Brut’. Matheson, p. 43. 38 These include, for example, an unusual brief reign for Henry IV; the defeat of Northumberland and Bardolph in 1408 at ‘Hasulwode’; the inclusion of ‘Sire de Gaucourt’ and ‘Dominus de Totevile’ in the list of prisoners at Agincourt; and a reference to the Benedictine Chapter of 1421, amongst other quirks. See Kingsford, p. 311. 39 E, f. ivv (flyleaf). 40 On the ‘nova cronica’ see E. D. Kennedy, ‘“History Repeats Itself”: The Dartmouth Brut and Fifteenth-Century Historiography’, Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Cultures, 3.2 (2014), 196–214 (pp. 207-210) <https://doi.org/10.1159/000075162>. 41 Matheson, pp. 44-46. This version has not been edited, but I have compared Downside and E throughout this article with the New Croniclis contained in Oxford Bodleian Library MS Ashmole 791. 36 37 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) However, Downside resembles E far more closely that either L, H, B, or J. In his catalogue, M. R. James dated E to c. 1475-1525, so it is possible that Downside was copied from this manuscript, or vice versa.42 Of the discrepancies that do exist between Downside and E, many of these are mechanical scribal errors, such as the repetition of ‘anno’ at f. 87v (‘hoc eodem anno anno’ [this same year year]), which would have probably been introduced during the copying process.43 There are several textual variations in Downside that are not shared with any of the other long Henry V manuscripts partially edited by Kingsford (L, H, B, and J), and almost all these unique textual variants are present in the Corpus Christi manuscript (E). Some of these variations also appear in B but were not picked up by Kingsford. There are other clues pointing to a cognate relationship between Downside and E. The following passage marks the transition between Henry IV and Henry V’s reigns, and the moment where the text departs from the ‘common’ version to the expanded life of Henry V. Here, the text is most similar in Downside, B, and E, although Downside and E match especially closely in terms of text and page design: Et cum Rex iste Henricus. regnasset XIII annis et dimidium apud Westmonasterium spiritum exalauit et in ecclesia Christi Cantuarie sepelitur Henricus quintus filius Henrici quarti […] (Downside 78291, f. 86r) Et cum Rex iste Henricus regnasset XIII annis et dimidio apud Westmonasterium spiritum exalauit et in ecclesia Christi Cantuarie sepelitur Henricus quintus filius Henrici quarti […] (E, f. 90r). Et cum rex iste henricus regnasset tresdecim annis et dimidio apud Westmonasterium spiritum exalauit. et in ecclesia Christi Cantuarie sepelitur Henricus quintus filius Henrici quarti […] (B, f. 78v).44 There is no visible break at this juncture in either Downside or E in terms of page design, change in hand or ink, which may suggest that the scribes of both manuscripts were working from an exemplar that already contained this seamless transition.45 The similarities between Downside and E are so striking – even in terms of spelling and page design – that we can state with some confidence that Downside and E share a direct stemmatic link. Although Downside is a lower grade of manuscript than E and uses a slightly different script, there are also some similar scribal quirks that raise the possibility that these manuscripts were copied by the same scribe: note for example the unusual g letterform with a right-curling descender throughout in both witnesses.46 Both exemplars follow the same patterns of rubrication, and the marginal notes are Fig. 1: Similar g letterforms in Downside (above, f. 20v) and E (below, f. 26v). (p. 173 in this article) M. R. James, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College Cambridge, 2 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1912), II, pp. 111-12. 43 This corresponds to f. 91r in E. 44 Underlined text represents an abbreviation that has been expanded. Bold text represents rubrication. Punctuation and capitalisation have been maintained (full stops in subsequent quotations indicate puncti). 45 Wakelin points out the importance of page design in identifying cognate manuscripts; see Scribal Correction, p. 50. As a point of comparison, Henry V’s reign begins on a separate folio in L (ff. 155v-166r). 46 See figure 1. 42 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) identical. Place names are almost invariably spelled the same in both Downside and E. Toponyms, unlike those in L, H, B, and J, have not been anglicised: in Downside and E we see, for example, ‘Kittaux’ in place of ‘Kitcawe’ (Downside f. 87v, E f. 91v)47 and ‘Agincourt’ in place of ‘Agyncourt’ (Downside f. 88v, E f. 92r).48 The Dukes of Alençon are not ‘duces [p. 173] Alencoun’ but ‘duces Alenconii’ (Downside f. 89r, E f. 92v; also B, f.80v); and the King of Calais is ‘Callisie Rex’ rather than ‘Calles Rex’ (Downside f. 89v, E f. 93r).49 We also see ‘Thwangcastre’ in place of ‘Thwangcastell’ (Downside, f. 14r; E f. 21v).50 This may suggest that the scribe responsible for these changes was skilled in Latin, altering the text as he saw fit. As Daniel Wakelin has shown, it was not unusual for scribes to amend ‘poor English’ or Latin in their exemplars during the copying process.51 Elsewhere in the Downside manuscript, as well as E and B, a previously unnoticed interpolation has been made at some stage during the copying process. An alternative version of the interpolation, worded differently, also appears in the witnesses containing the shorter version of Henry V’s life.52 The interpolation is preserved in the New Croniclis, which suggests that Downside, E, and B are most closely related to the English translation. The interpolator appears to have had some knowledge of the campaigns fought in France, and may have been a clerk in the service of a knight who fought across the channel. The embellishment has been made to the description of the Siege of Harfleur. The interpolation is reproduced below from Downside, E and B, with comparative extracts included from the shorter life of Henry V and the New Croniclis respectively. Bold text indicates the interpolated material: 53 [p. 174] B: Kydkaus (f. 79v). B: Agyncorte (f. 80r). 49 B: Calesie rex (f. 81r). 50 B: Tawangcastre (f. 17v). 51 Wakelin, Scribal Correction, p. 60. 52 See Kingsford, p. 316; G, f. 49v. 53 Additions differing from Kingsford’s collation of L, J, B and H (Kingsford, p. 325) are given in bold. As previously, underlining indicates expanded text, and all punctuation (and paraph marks) are reproduced from the manuscripts. 47 48 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) Downside, f. 87v88r […] Deinde vsque Harifluuium progressus ipsam circum obsedit diris insultibus ipsam infestando. cuius parietes horrisonis machinarum iaculacionibus pilas lapideas terribiliter euomencium solotenus consternuntur. turres campanilia forcia que edificia violenter conquaciendo. tanta vero missilium et machinarum horribilitas nusquam a seculo est visa vel audita in finibus Francorum54 E f. 91v […] Deinde usque harifluuium progressus ipsam circum obsedit diris insultibus ipsam infestando. cuius parietes horrisonis machinarum iaculacionibus pilas lapideas terribiliter euomencium solotenus con55 consternuntur. turres campanilia forcia que edificia violenter conquaciendo. tanta vero missilum et machinarium horribilitas nusquam a seculo est visa vel audita in finibus Francorum B, ff. 79v-80r […] Deinde usque harifluuium progressus ipsam circum obsedit. diris insultibus ipsam infestando cuius parietes horrisonis machinarum iaculacionibus pilas lapideas terribiliter euomencium solotenus consternuntur. turres campanilia forcia que edificia violenter conquaciendo. ¶ Tanta vero missilium et machinarum horribilitas nusquam a seculo est visa vel audita in finibus francorum From the shorter life of Henry V56 […] ac villam de hareflieu obsedit diris insultibus ipsam infestando. cuius parietes horribilibus bumbardorum iaculacionibus pilas lapideas terribiliter euomencium solo tenus consternuntur. turres campanilia forcia et edificia violenter conquaciendo. Talium pilarum ludus nusquam a seculo est visus vel auditus in confinijs Francorum New Croniclis (MS Ashmole 791, ff. 55r-v) […] & so wente he forþe to harflewe & besegyd it. Leynge þere to grete sawtys. wyþ grete Sounnys castynge a downe þe wallys & ouer þrowynge steples. churchis. tentes. & stronge byldyngys. So grete horrybylyte of dartys. & engynys. before þat tyme was neuere sene. neþere herde of in Fraunce. Although the base text here is already dramatic, someone has taken pains to embellish it further. The addition may suggest that the interpolator, or their patron, was present at the Siege of Harfleur itself. At the very least, this alteration amplifies England’s historical victories against the French. Other textual variations in Downside, E, and B may also place emphasis on these past ‘From there to Harfleur they advanced, and hemmed in the city all the way around, and with dreadful insult they attacked it. Its walls echoed with the dreadful sound of war machines hurtling rocks and mortar, frightfully spewing them forth and strewing them like seeds. Towers, belfries and strong buildings were violently shattered; truly there were so many horrifying missiles and siege engines that nowhere in our age were seen or heard to the very limits of France’. Translation mine. 55 This occurs at the end of a line and appears to represent a mechanical scribal error. 56 Kingsford, p. 316; G, f. 49v. The text here is from Kingsford’s edition; he uses Bodleian Rawlinson C. 398 as his base text for Henry IV’s reign, and for the longer life of Henry V Kingsford’s base text comes from L. 54 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) victories. Compare, for example, the following extracts concerning the forced expulsion of Queen Isabella, second consort to Richard II, from England after her husband’s deposition: Hoc anno Isabella secunda uxor Regis. Ricardi57 dote sua nudata multis tamen58 munerata donariis59 ab Anglia pulsa est & in Franciam usque transmissa [In this year, Isabella the second wife of King Richard, stripped of much of her dowry yet still honoured with gifts, was expelled from England and carried over to France.] Hoc anno Isabella Regina, nuper vxor Regis Ricardi,61 dote sua nudata cum magnis tamen muneribus ab Anglia pulsa est et in Franciam transmissa. [In this year Queen Isabella, the new wife of King Richard, stripped of her dowry, yet with great gifts, was expelled from England, and carried over to France] (Downside f. 84v; E f. 89r; B f. 77v)60 (Kingsford, p. 313; G f. 48v)62 [p. 175] The changes shown here are also reflected in the New Croniclis.63 In Kingsford’s collated edition, Isabella is referred to as ‘Queen’ [Regina], and the ‘new wife’ [nuper uxor] of King Richard. However, in Downside, B and E she is referred to pointedly as Richard’s ‘second’ wife [‘secunda uxor’], and the word ‘Queen’ [Regina] is missing altogether.64 Whilst this may simply be an alteration for clarity’s sake, it may be politically significant: Richard’s first marriage to Anne of Bohemia, daughter of Charles IV Holy Roman Emperor, secured the support of the Holy Roman Empire in England’s fight against France during the Hundred Years’ War. Richard’s later marriage to Isabella, on the other hand, helped to secure Richard’s peace treaty with France, an agreement that was not wholly popular with the English nobility. Indeed, under Richard’s successor, Henry IV, Isabella was stripped of her queenship and forcibly sent back to France.65 Whilst ‘new wife’ [nuper uxor] might perhaps refer to the newness of the marriage, ‘second wife’ perhaps implies that Anne of Bohemia (and England’s military alliance with the Empire) came first. The textual changes here may subtly suggest that the author disapproves of Richard II’s peace agreement with France, and that Isabella held no right to be referred to as ‘Queen’ after Henry IV took the throne. There are other unique variants in Downside, E and B which glorify Henry IV and V and downplay any discontent which occurred during their reigns. For example, material concerning the execution of the four men responsible for the 1400 Epiphany Rising against Henry IV is absent in the text in Downside at f. 84v (before ‘Hoc anno Isabella Regina’), despite appearing in In B: Ricardi secundi In B: temen 59 In B: denarijs 60 Expansions, punctuation, and capitalisation here follow the Downside manuscript. 61 In G: Richardi 62 The text here follows Kingsford’s edition. 63 MS Ashmole 791, f. 54r. 64 Kingsford, p. 313; Downside 78291 f. 84v; E f. 91r. 65 Anthony Tuck, ‘Richard II (1367-1400), King of England and Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine’, The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 8 January 2008 <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb9780198614128-e-23499> [accessed 28 May 2019]. 57 58 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) L, H, J, and G.66 It is also missing in E and B, and in at least one manuscript containing the English New Croniclis.67 The rebels in question had been awarded titles by Richard II for assisting him against Gloucester and the Lords Appellant. The 1400 rebellion was therefore motivated by a desire to kill the new king Henry, replacing him with the deposed Richard.68 The plot aimed to take down six of the most important Lancastrian lords, and was therefore fundamentally an attempt to destroy Lancastrian power. 69 The reason for the event’s omission in this version of the Latin Prose Brut may therefore be motivated by a desire to paint Henry IV in a positive light by omitting evidence of dissatisfaction in his reign from the history books. According to John Blacman, Henry VI’s confessor, the imprisoned Henry VI was reluctant to accept that there had been any opposition to the reigns of his father or grandfather, which chimes with the omissions in Downside and E: My father was king of England, and peaceably possessed the crown of England for the whole time of his reign. And his father and my grandfather was king of the same realm. And I, a child in the cradle, was peaceably and without any protest crowned and approved as king by the whole realm, and wore the crown of England some forty years, and each and all of my lords did me royal homage and plighted me their faith, as was also done to other my predecessors.70 These modifications and omissions support Kennedy’s assertion that the Latin Prose Brut exhibits a ‘Lancastrian bias’.71 Kennedy also points to the Latin Prose Brut’s Joseph of Arimathea material as evidence of a Lancastrian agenda, based on Henry V’s use of the Glastonbury church foundation legend as justification for England’s antecedence as a Christian nation.72 Whilst the Joseph of Arimathea material is absent in some Latin Prose Bruts with the shorter life of Henry V (it is not in Domitian A. iv nor Harley 3906), [p. 176] the Latin Prose Bruts with the longer life of Henry V all include this Joseph of Arimathea material (L, J, B, H, E and Downside). This lends support to Kennedy’s suggestion. Given that the manuscript was composed some time in the second half of the fifteenth century, it is not surprising that the text has been tweaked to glorify England’s historic French campaigns. Some chroniclers writing at this time were perturbed by England’s recent defeats in France and the peaceful period that had followed. William Worcester (1415-1492) is one such Kingsford, p. 313; G f. 48v. Here is the excised passage, following Kingsford’s edition: ‘Hoc eodem anno Bernardus Brokes, Johannes Shelley, milites, Johannes Mawdeleyn, et Willelmus Fereby, nuper capellini Regis Ricardi, capiuntur, qui postmodum decapitate fuerunt’ [In this same year, Bernard Brocas, John Shelley, knights, John Magdalen, and William Fereby, King Richard’s new chaplain, were captured, and were beheaded soon after]. Translation mine. 67 B, ff. 77r-v; MS Ashmole 791, f. 54r. 68 The executed rebels were attainted by Henry IV, but this decision was formally reversed in 1461 by a Yorkist parliament, probably shortly before Downside 78291 was written. On the Epiphany rising see C. Given-Wilson, Henry IV (New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2016), pp. 160-164. 69 See C. Given-Wilson, ‘Richard II, Edward II, and the Lancastrian Inheritance’, The English Historical Review, 109.432 (1994), 553-71 (p. 556). 70 John Blacman, Henry the Sixth: A Reprint of John Blackman’s Memoir with Translation and Notes, ed. and trans. by M. R. James (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1919), p. 44. 71 Kennedy, p. 121. 72 Kennedy, ibid. 66 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) example. Worcester spent much of his life in the service of John Fastolf, a knight with lands in England and France. A veteran of the Hundred Years’ War, Fastolf fought in several major battles, including the Siege of Harfleur. Whilst Worcester cannot have accompanied Fastolf to Harfleur, he certainly accompanied his patron on several later French campaigns. Worcester believed strongly that England should re-invade France: his best-known work, The Boke of Noblesse, urged the King to continue his French campaigns. Composed and revised between 1453 and 1475 for dedication to both Henry VI and Edward IV, the Boke identified past problems with strategy and rulership, advising the king on military issues and pressing for another French invasion.73 Catherine Nall has demonstrated that Worcester crafted the Boke to strategically prompt an ‘emotional response from his readers’ by using ‘apostrophes, laments, and exhortations’.74 This technique is similar to the embellishment added to the Siege of Harfleur passage in Downside and E. Although it would be an overstatement to suggest that Worcester was the originator of the changes witnessed in Downside and E, he does represent the type of person who might have had motive and opportunity to make such alterations to the text. Aside from Worcester’s martial agenda, we know that he composed Latin chronicles.75 We also know that he sought out Latin Prose Brut chronicles: Master Brewster, keeper of the manuscripts for the earls of Warwick, allowed Worcester to copy extracts from chronicles in his keeping, including one which recorded Henry V's campaigns in France (though the extracts which Worcester copied in his Itinerary do not match the Downside witness).76 Of course, it is important to remain circumspect: there were certainly other chroniclers whose patrons had been involved in the Siege of Harfleur, and who were equally passionate about England exercising her sovereignty over France. For example, John Hardyng (c. 1377-1464) also worked in the service of a veteran of the Hundred Years’ War: Sir Robert Umfraville, who fought in the Battle of Agincourt and the Siege of Harfleur.77 This said, Hardyng did not, to our knowledge, write in Latin, although he may have used Latin sources when preparing his English Metrical Chronicle. It should be noted that neither Downside nor E appear to have been written by Worcester himself: although Worcester’s hand varies during the course of his life and depending on the grade of manuscript that he is writing, Downside does not appear to have been copied by Catherine Nall, ‘William Worcester Reads Alain Chartier: Le Quadrilogue invectif and its English Readers’, in Charter in Europe, ed. by Emma Cayley and Ashby Kinch (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2008), pp. 135-48, p. 143. Nall’s edition of the Boke of Noblesse is forthcoming. 74 Catherine Nall, ‘Moving War: Rhetoric and Emotion in William Worcester’s Boke of Noblesse’, in Emotions and War: Medieval to Romantic Literature, ed. by Stephanie Downes, Andrew Lynch, and Katrina O’Loughlin (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015), pp. 116-32 (p. 116). 75 Nicholas Orme, ‘William Worcester [Botoner] (1415-1480x85), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 28 September 2006 (Oxford University Press) <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb9780198614128-e-29967> [accessed 29 May 2019]. 76 Antonia Gransden, Historical Writing in England, 2 vols (London: Routledge, 1982), II, pp. 339-40; William Worcester, Itineraries, ed. and trans. by John H. Harvey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), pp. 20919. Another manuscript containing Worcester’s collectanea, including extracts copied from diverse chronicles, is London College of Arms MS Arundel 48, which I have not yet been able to consult for parallels with Downside and E. 77 Henry Summerson, ‘Sir Robert Umfraville (d. 1437)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004 < https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128e-27992> [accessed 29 May 2019]. 73 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) Worcester. Many distinctive letterforms from Downside, such as anglicana w and the q-like flattop secretary g with unusually straight descenders curling to the right at the bottom, are not present in either the Paston correspondence, Worcester’s notebook, nor his notes in The Boke of Noblesse.78 Yet this does not rule out Worcester’s involvement somewhere along the line in the process of copying, revision, and continuation of this particular Latin Prose Brut recension. At the very least, Worcester provides a telling example of the kinds of interests and political motivations that fuelled the copying (and altering) of late medieval prose chronicles. Whilst any conjecture about Worcester’s involvement cannot be demonstrated until further evidence comes to light, [p. 177] what is clear is that a new cluster of Prose Latin Brut manuscripts is emerging that represents a new subgroup: the version of the chronicle present in Downside, E, and B must share a close stemmatic relationship. In conclusion, Downside 78291 provides an interesting new contribution to our understanding of the Latin Prose Brut tradition. It is remarkably similar to Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 311 (E) in terms of unique textual variants and page design shared by the two manuscripts, and is also closely similar to Bodleian Rawlinson MS B. 169 (B). We must disregard the prior suggestion that Gonville and Caius MS 72/39 is a ‘copy’ of E, and instead we should consider Downside in relation to E and B. The similarities between Downside, E and B, and the further similarities between this group and the New Croniclis, suggest that we need to reconsider how these manuscripts interrelate. Acknowledgements Firstly, I extend my thanks to the South West and Wales Doctoral Training Partnership, for providing financial support for the archival placement undertaken at Downside Abbey. I thank the reviewers for their detailed and helpful feedback. This article would not be in its current form without the generous help and expertise of Catherine Nall, Erik Kooper, Trevor Russell Smith, and Sjoerd Levelt, whose previous scholarship on William Worcester and the Prose Brut respectively was invaluable to me in the present study. I would also like to thank Ad Putter and George Ferzoco for supporting my research and feeding back on earlier drafts of this article. Both George Ferzoco and Simon Johnson, keeper of the library and archive at Downside Abbey, were most generous in inviting me to assist in cataloguing the amazing collections; without their support I would have never come across Downside 78291 in the first place. Works Cited Primary Sources British Library Add. MS 43488, ff. 15-16, 20, 31, 37-39, 40, and 49-52. Although I do not claim that Worcester was involved in the copying of this particular witness, it should nevertheless be noted that Worcester and his patron are known to have employed scribes. Worcester mentions hiring scribes in his Itineraries, ed. by Harvey, p. 388 (or Cambridge Corpus Christi College MS 210, p. 309): 'Fyrst payd for the wrytyng of a cop[y] of the entree of the plee called the Inparlance ayenst thabbot of Langley.' See also Catherine Nall, ‘Ricardus Franciscus Writes for William Worcester’, The Journal of the Early Book Society for the Study of Manuscript and Printing History, 11 (2008), 207-12. 78 Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 210 Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 311, ff. 1-101 Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College MS 72/39 Glasgow, Glasgow University Library MS Hunter 83 Huntington CA, Huntington Library MS 19960 Huntington CA, Huntington Library MS 48570 London, British Library Add. MS 43488 London, British Library MS Cotton Domitian IV London, British Library MS Lansdowne 212, ff. 2-171v London, British Library MS Harley 3884, ff. 227-228v (fragment) London, College of Arms MS Arundel 5 Warminster, Wiltshire, Longleat House, MS 55 Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Ashmole 791 Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson B. 147 Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson B. 169, ff. 1-88 Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson B. 195 Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson C. 398 Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Rawlinson C. 234 Oxford, St John’s College MS 78, ff. 2-55v Stratton-on-the-Fosse, Somerset, Downside Abbey 78291 San Marino CA, Huntington Library HM 48570 Secondary Works A Catalogue of the Library of Mr. Thomas Martin, of Palsgrave, in Suffolk, deceased (Lynn: W. Whittingham, 1772) ESTC T98426 A Catalogue of the very curious and numerous collection of MSS. Of Thomas Martin, Esq. of Suffolk, lately deceased (London: Baker and Leigh, 1773), ESTC T28840 Bibliotheca Martiniana: A Catalogue of the entire Library of the late eminent antiquary, Mr. Thomas Martin, of Suffolk (Norwich: Booth and Berry, 1773), ESTC T98425 Blacman, John, Henry the Sixth: A Reprint of John Blackman’s Memoir with Translation and Notes, ed. Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) and trans. by M. R. James (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1919) Briquet, C. M., Les filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600 avec 39 figures dans le texte et 16 1123 fac-similés de filigranes, 4 vols (Geneva: A. Jullien, 1907) Dean, Ruth J. and Maureen B. M. Boulton, Anglo-Norman Literature: A Guide to Texts and Manuscripts (London: Anglo Norman Text Society, 1999) Given-Wilson, C., Henry IV (New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2016) ---------------------, ‘Richard II, Edward II, and the Lancastrian Inheritage’, The English Historical Review, 109.432 (1994), 553-71 Gransden, Antonia, Historical Writing in England, 2 vols (London: Routledge, 1982) Himsworth, Katherine, ‘Brut y Brenhinedd’, in Arthur in the Celtic Languages: The Arthurian Legend in Celtic Literatures, ed. Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan and Erich Poppe (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2019), pp. 95-110 James, M. R., A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College Cambridge, 2 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1912) ---------------, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Gonville and Caius College, 2 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1907) Juei-Jensen, Bent, ‘Obituaries: David Rogers’, The Independent, 9 June 1995 <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituaries-david-rogers-1585536.html> [accessed 3 May 2019] Kennedy, E. D. and Peter Larkin, ‘Prose Brut, Latin’ in The Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle, ed. by Graeme Dunphy and Cristian Bratu (Brill, online 2016) <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2213-2139_emc_SIM_02111> [accessed 31 October 2019] Kennedy, E. D., ‘“History Repeats Itself”: The Dartmouth Brut and Fifteenth-Century Historiography’, Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Cultures, 3.2 (2014), 196–214 <https://doi.org/10.1159/000075162> -----------------------, ‘Glastonbury’, in The Arthur of Medieval Latin Literature, ed. Siân Echard (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2011), pp. 110-31 -----------------------, Chronicles and Other Historical Writings, A Manual of the Writings in Middle English, 1050-1500, 8 (New Haven CT: Archon, 1989) Ker, N. R., Medieval Manuscripts in British Libraries, 5 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969-2002) Kingsford, C. L., English Historical Literature in the Fifteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon, 1913) Kooper, Erik, ‘Longleat House MS 55: An Unacknowledged Brut Manuscript?’ in The Prose Brut Mary Bateman, ‘A Newly Discovered Latin Prose Brut Manuscript at Downside Abbey’, The Downside Review, 137.4 (2019), 166-181 (accepted version – pagination inset) and Other Late Medieval Chronicles: Books Have Their Histories, Essays in Honour of Lister M. Matheson, ed. Jaclyn Rajsic, Erik Kooper, and Dominique Hoche (York: York Medieval Press, 2016), pp. 75-93 Marvin, Julia (ed. and trans.), The Oldest Anglo-Norman Prose Brut Chronicle: An Edition and Translation, Medieval Chronicles 4 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006) -------------------------------, ‘Sources and Analogues of the Anglo-Norman Prose “Brut” Chronicle: New Findings’, Trivium, 36 (2006), 1–31 Matheson, Lister M., The Prose Brut: The Development of a Middle English Chronicle, Medieval Texts & Studies 180 (Tempe, AZ: Arizona State University, 1998) Nall, Catherine, ‘Moving War: Rhetoric and Emotion in William Worcester’s Boke of Noblesse’, in Emotions and War: Medieval to Romantic Literature, ed. Stephanie Downes, Andrew Lynch, and Katrina O’Loughlin (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015), pp. 116-32. ------------------, ‘William Worcester Reads Alain Chartier: Le Quadrilogue invectif and its English Readers’, in Charter in Europe, ed. Emma Cayley and Ashby Kinch (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2008), pp. 135-48. ------------------, ‘Ricardus Franciscus Writes for William Worcester’, The Journal of the Early Book Society for the Study of Manuscript and Printing History, 11 (2008), 207-12. Orme, Nicholas, ‘William Worcester [Botoner] (1415-1480x85), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 28 September 2006 (Oxford University Press) <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odn b-9780198614128-e-29967> [accessed 29 May 2019]. Summerson, ‘Sir Robert Umfraville (d. 1437)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004 (Oxford University Press) <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odn b-9780198614128-e-27992> [accessed 29 May 2019]. Tuck, Anthony, ‘Richard II (1367-1400), King of England and Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine’, The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 8 January 2008 <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odn b-9780198614128-e-23499> [accessed 28 May 2019]. Tyson, Diana, ‘Handlist of Manuscripts Containing the French Prose Brut Chronicle’, Scriptorium, 48 (1994), 333-44. Wakelin, Daniel, Scribal Correction and Literary Craft (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014) Worcester, William, Itineraries, ed. and trans. by John H. Harvey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969)