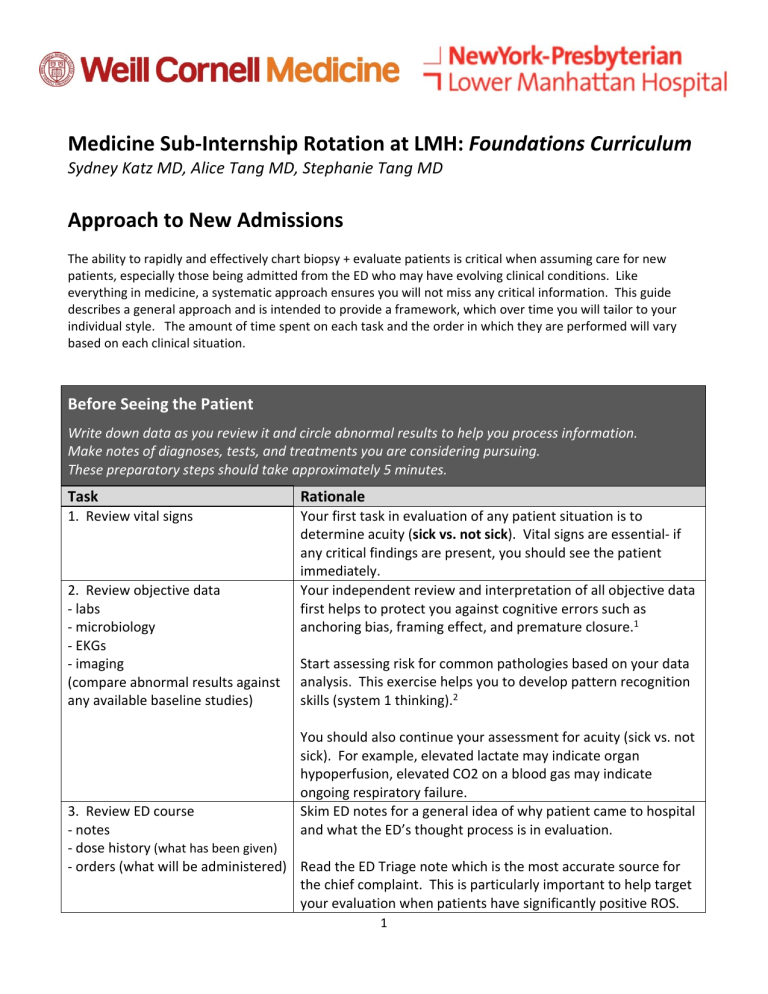

Medicine Sub‐Internship Rotation at LMH: Foundations Curriculum Sydney Katz MD, Alice Tang MD, Stephanie Tang MD Approach to New Admissions The ability to rapidly and effectively chart biopsy + evaluate patients is critical when assuming care for new patients, especially those being admitted from the ED who may have evolving clinical conditions. Like everything in medicine, a systematic approach ensures you will not miss any critical information. This guide describes a general approach and is intended to provide a framework, which over time you will tailor to your individual style. The amount of time spent on each task and the order in which they are performed will vary based on each clinical situation. Before Seeing the Patient Write down data as you review it and circle abnormal results to help you process information. Make notes of diagnoses, tests, and treatments you are considering pursuing. These preparatory steps should take approximately 5 minutes. Task Rationale 1. Review vital signs Your first task in evaluation of any patient situation is to determine acuity (sick vs. not sick). Vital signs are essential‐ if any critical findings are present, you should see the patient immediately. Your independent review and interpretation of all objective data first helps to protect you against cognitive errors such as anchoring bias, framing effect, and premature closure.1 2. Review objective data ‐ labs ‐ microbiology ‐ EKGs ‐ imaging (compare abnormal results against any available baseline studies) Start assessing risk for common pathologies based on your data analysis. This exercise helps you to develop pattern recognition skills (system 1 thinking).2 You should also continue your assessment for acuity (sick vs. not sick). For example, elevated lactate may indicate organ hypoperfusion, elevated CO2 on a blood gas may indicate ongoing respiratory failure. Skim ED notes for a general idea of why patient came to hospital and what the ED’s thought process is in evaluation. 3. Review ED course ‐ notes ‐ dose history (what has been given) ‐ orders (what will be administered) Read the ED Triage note which is the most accurate source for the chief complaint. This is particularly important to help target your evaluation when patients have significantly positive ROS. 1 4. Call ED for sign out 5. Consider briefly skimming prior discharge summaries or recent outpatient notes for information relevant to current presentation Obtain verbal sign out from the ED physician. Since you have already reviewed the data, you should focus on listening for history and assessment. Ask any questions that arose in your mind as you were reviewing the data. If there are worrisome vital signs, ask for them to be repeated. If you believe there are tests or therapies that need to be expedited, discuss this with the ED and request them to initiate. This is especially helpful if: ‐ patient had a recent hospitalization for a related issue ‐ there are underlying psychiatric issues that may complicate the patient’s assessment or development of therapeutic rapport You should perform a more thorough and comprehensive review of available data after seeing the patient. Sample Chart Biopsy Structure: 2 Evaluating the Patient Your time at the bedside evaluating the patient is not purely information gathering. In real time, you should be integrating data acquired from the history and physical into your clinical assessment (adding items to the problem list, reorganizing your differential diagnoses). This active process directs your next lines of thinking and how to focus your history & exam. Task Rationale 6. Obtain history + physical CC: Ask why patient came to the hospital (i.e. their main concern). Ask open‐ended questions as much as possible in beginning of encounter. HPI/ROS: 2 pronged approach ‐ Establish a timeline. Let the patient lead this part of the interview as this will identify what symptoms were the most concerning to them. Ascertain what the patient’s usual state of health is (independent, ambulates with walker, bedbound, nonverbal, etc.) to determine what has changed from baseline. *Note: If patients are disorganized, you may need to re‐direct them. Be sure that you understand clearly what happened in what order and how events related to each other. ‐ Elicit pertinent positives/negatives. Based on the information the patient has provided you thus far and your data review you should already have some preliminary diagnoses in mind. Focus on a differential‐based line of questioning and obtain discriminating information that will help better assess which diagnoses are more or less likely. ‐ Complete ROS with any systems not yet discussed PMH/PSH/Meds/All/FH/SH: Take a similar approach as to HPI. After obtaining baseline information, probe about details that will allow you to assess which diagnoses are more or less likely. MDs/Pharmacy/HCP/Emergency Contact: Essential for obtaining collateral. Try to collect this information on initial encounter in case the patient decompensates. Code Status: Must discuss if elderly patients or those who you feel may clinically deteriorate. 3 7. Obtain collateral information ‐ prior inpatient & outpatient records ‐ outpatient providers ‐ pharmacy ‐ family, HHAs, case managers, etc. 8. Synthesize your analysis Exam: Again, take a similar approach as to obtaining history. After completing your baseline comprehensive exam, perform any special maneuvers which will help you discriminate between competing diagnoses (i.e. orthostatics, JVD, reflexes, etc). Take note of IV access and hardware (foleys, central lines, etc). In cases where patients are poor historians or there are psychiatric issues contributing, collateral information from close contacts and outpatient providers is essential. Inaccurate information about medications is especially high risk both at time of admission and discharge. Medications lists provided by patients should be verified against their pharmacies, especially if there is any uncertainty about reliability. In addition, pharmacies are an excellent resource to obtain physician contact information. By now you have collected a wealth of information about the patient and his/her problems and done some preliminary analysis. Think of the next step in synthesizing as an organizational one. 1st create your Problem List. In the initial encounter, these will be a compilation of complaints, exam findings, and test abnormalities. After creating your list, you must prioritize it based on acuity and importance. Incidental findings and chronic medical problems should be listed last and specified as such so that other care providers can easily distinguish which are the active medical problems being managed. Then develop your Impression. Consider the Problem List as the pieces of the puzzle and your Impression as your attempt to fit the puzzle pieces together. How do all these clues you have found help you elucidate the story of what happened to this patient? Try to create as many possible stories as you can out of the puzzle pieces. In your description, maximize use of semantic qualifiers and illness scripts to optimize your assessment.3 Lastly, create you Plan. For each item on your Problem List, break down your plan into 2 sections‐ diagnostics (why did this happen) and therapeutics (how to make this problem better). 4 Suggested Readings 1. Croskerry, P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003 Aug;78(8):775‐80. 2. Pelaccia T, Tardif J, Triby E, Charlin B. An analysis of clinical reasoning through a recent and comprehensive approach: the dual‐process theory. Med Educ Online. 2011 Mar 14;16. doi: 10.3402/meo.v16i0.5890. 3. Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006 Nov 23;355(21):2217‐25. 5