Motivation, Culpability, and Punishment in Criminal Actions

advertisement

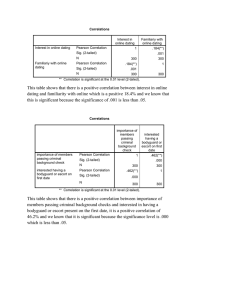

The Critical Role of Motivation in Assigning Culpability and Punishment for Criminal Actions Christian D. Johnston & Jack A. Palmer, Ph.D. Department of Psychology, College of Business and Social Sciences, The University of Louisiana at Monroe Introduction Often, there is a great disparity regarding how a criminal action is viewed from a purely legal perspective in comparison to how it is viewed from an individual psychology perspective. The legal system generally views motive as irrelevant in determining criminal liability. By contrast, from a psychological perspective, motive plays a large role in the assessment of blameworthiness of the perpetrator in regards to their actions. (Malle, B., Guglielmo, S. & Monroe, A. 2012; Malle, B., Guglielmo, S. & Monroe, A. 2014.) Introduction Trials are conducted with the purpose of: Courts must determine whether mens rea—the term used to describe the mental element which is required for an action to constitute a crime—was present at the time of the criminal act. 1. determining whether the defendant actually committed the illegal act in question 2. determining whether the perpetrator had the required mental state Mens rea generally requires the accused to be shown as intending to do wrong or, at the least, that they possessed the knowledge that they were doing wrong. Motive may be introduced into a trial as evidence of guilt; however, motive is not perceived as an actual legal component of guilt. (Hessick, 2006) Introduction The court must attempt to determine if the defendant is guilty or not guilty. Issues relating to culpability of the defendant’s blameworthiness are generally made only at sentencing, as illustrated by the case of Regina vs. Dudley and Stephens. In this case, sailors who were shipwrecked and marooned on a life raft—with no food or water—decided eventually to kill and eat one of their own. Later, when they were rescued, they were prosecuted for the killing. The defendants argued they should not be punished due to the killing being required for their survival. The court did not accept this defense that were starving; they were found guilty of murder. However, their sentence was commuted from death to only six months imprisonment. Kadish & Schulhofer, 2011 Introduction In the current state of our legal system, motive plays only a minor role in the determination of relative culpability of defendants. To compensate for this deficit, Hessick (2006) has argued that motive should play an expanded role in punishment assessment. Through accounting for motivation during the sentencing phase of a trial, punishment will more accurately reflect an appropriate amount of moral condemnation for actions of the defendant. Hessick writes: “Because a punishment system that reflects shared values is more effective at deterring crime, and because motives are perceived as relevant to a defendant’s blameworthiness, a punishment system that accounts for motives may also result in less crime” (2006). Purpose of this Study The rationale for the present study was to assess the role of motive domain and its influence on perceptions of culpability of the perpetrator, as well as appropriate punishment. The motivation underlying the perpetrator’s criminal act was hypothesized to have a major influence on the perception of that perpetrator’s level of culpability and what level of punishment was deserved. To investigate this, vignettes were created falling into four categories of motivation: Greed, Revenge, Jealousy, and crimes committed through Military engagements. Purpose of this Study To explore the interrelationships of vignette responses and: Demographic values: HEXACO Personality Test: Sex Honesty-Humility Ethnicity Emotionality ACT scores Extraversion Level of religiosity Agreeableness Level of spirituality Conscientiousness Openness to Experience Method Participants 102 university students enrolled in introductory psychology classes in Louisiana volunteered to participate in the study. Self-report Instruments Basic Empathy Scale (BES) = cognitive & affective empathy Level of Religiosity (REL) = self-reported degree of religiosity Level of Spirituality (SPI) = self-reported degree of spirituality The HEXACO-60 Honesty-Humility (H): Sincere, honest, faithful, loyal, modest/unassuming versus sly, deceitful, greedy, pretentious, hypocritical, boastful, pompous Emotionality (E): Emotional, oversensitive, sentimental, fearful, anxious, vulnerable versus brave, tough, independent, self-assured, stable Extraversion (X): Outgoing, lively, extraverted, sociable, talkative, cheerful, active versus shy, passive, withdrawn, introverted, quiet, reserved Agreeableness (A): Patient, tolerant, peaceful, mild, agreeable, lenient, gentle versus ill-tempered, quarrelsome, stubborn, choleric Conscientiousness (C): Organized, disciplined, diligent, careful, thorough, precise versus sloppy, negligent, reckless, lazy, irresponsible, absent-minded Openness to Experience (O): Intellectual, creative, unconventional, innovative, ironic versus shallow, unimaginative, conventional Vignettes Participants were asked to read vignettes falling into four categories of perpetrator motivation: Greed, Revenge, Jealousy, and Military engagement. In all categories, the outcome of the criminal action was the same—death of a human being. Each category had 3 vignettes for a total of 12 vignettes. Sample Vignettes Greed A businessperson owns a company that manufactures a protein supplement drink. The owner orders the workers to add a certain chemical to the formula that will falsely show higher protein values when the product is tested. The chemical is known to be toxic and the subsequent outcome of this action is a disastrous. The protein drink causes the death of at least one individual before the product is pulled from the market. What is the culpability (responsibility) of this person? Circle one. If found guilty in a court of law what should the punishment be? Circle one. 1= Not at All 1= Less than one year in prison 2= Very Little 2= From 1 to 15 years in prison 3= Somewhat 3= More than 15 years in prison 4= To a Great Extent 4= Life in prison 5= Entirely 5= Death by execution Sample Vignettes Revenge A parent loses a child in a college campus mass shooting. The perpetrator has been arrested and is being transported to the courthouse to stand trial. The bereaved parent finds a hiding place outside the courthouse and lies in wait with a sniper rifle. As the perpetrator is being led up the courthouse steps the grieving parent kills the perpetrator with a single shot. What is the culpability (responsibility) of this person? Circle one. If found guilty in a court of law what should the punishment be? Circle one. 1= Not at All 1= Less than one year in prison 2= Very Little 2= From 1 to 15 years in prison 3= Somewhat 3= More than 15 years in prison 4= To a Great Extent 4= Life in prison 5= Entirely 5= Death by execution Sample Vignettes Jealousy An individual comes home to find their spouse in bed with a stranger. A struggle ensues and the stranger is killed by that individual. What is the culpability (responsibility) of this person? Circle one. If found guilty in a court of law what should the punishment be? Circle one. 1= Not at All 1= Less than one year in prison 2= Very Little 2= From 1 to 15 years in prison 3= Somewhat 3= More than 15 years in prison 4= To a Great Extent 4= Life in prison 5= Entirely 5= Death by execution Sample Vignettes Military A Special Forces sniper has one chance to take out a high-value enemy target. The high-value target is standing in front of a civilian bystander. The sniper decides to take the shot and both the target and the bystander are killed by the same bullet. What is the culpability (responsibility) of this person? Circle one. If found guilty in a court of law what should the punishment be? Circle one. 1= Not at All 1= Less than one year in prison 2= Very Little 2= From 1 to 15 years in prison 3= Somewhat 3= More than 15 years in prison 4= To a Great Extent 4= Life in prison 5= Entirely 5= Death by execution Results and Discussion Results and Discussion Part 1: Impact of Motivation Domain on Judgments of Culpability Data analysis revealed a significant effect for motivation domain [One-way repeated measures ANOVA, Wilkes' Lambda=.606, F(3, 99)= 21.5, p<.0001, Multivariate partial eta squared=.394] Domain Mean SD N Greed Culpability Revenge Culpability Jealousy Culpability Military Culpability 4.43 3.74 4.32 3.98 .681 1.08 .774 .872 102 102 102 102 Results and Discussion Part 1: Impact of Motivation Domain on Judgments of Culpability Pair-wise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment of the mean scores for Culpability of the four types of Motivation revealed: Greed scored significantly higher than Revenge Both Greed and Revenge were significantly higher than Military (p< .001) Jealousy did not differ significantly from either Greed or Revenge. Greed > Revenge and Jealousy > Military Results and Discussion Part 2: Impact of Motivation Domain on Judgments of Punishment Data analysis revealed a significant effect for motivation domain [One-way repeated measures ANOVA, Wilkes' Lambda=.327, F(3, 98)=67.11, p<.0001, multivariate partial eta squared=.673] Domain Mean SD N Greed Punishment Revenge Punishment Jealousy Punishment Military Punishment 2.71 2.25 3.17 2.07 .789 .982 .833 .806 102 102 102 102 Results and Discussion Part 2: Impact of Motivation Domain on Judgments of Punishment Pair-wise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment of the mean scores for Punishment of the four types of Motivation revealed: Jealousy scored significantly higher than Greed and Revenge Both Jealousy and Greed were significantly higher than Revenge and Military (p< .001) Revenge did not differ significantly from Military. Jealousy > Greed > Revenge and Military Correlations between Judgments of Culpability and Punishment Greed Punishment Greed Punishment Pearson Correlation Revenge Punishment .624** .012 .000 .000 102 102 102 101 Pearson Correlation .247* 1 .493** .247* Sig. (2-tailed) .012 .000 .013 N N Jealousy Punishment 1 102 102 102 101 .503** .493** 1 .373** .000 .000 102 102 102 101 .624** .247* .373** 1 .000 .013 .000 101 101 101 101 .360** .007 -.015 .198* .000 .948 .879 .047 102 102 102 101 Pearson Correlation .088 .451** .206* .162 Sig. (2-tailed) .378 .000 .038 .107 102 102 102 101 Pearson Correlation .158 .245* .191 .076 Sig. (2-tailed) .112 .013 .055 .450 102 102 102 101 Pearson Correlation .121 -.058 -.053 .378** Sig. (2-tailed) .226 .566 .594 .000 102 102 102 101 Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N Military Punishment Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N Greed Culpability Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N Revenge Culpability N Jealousy Culpability N Military Culpability Military Punishment .503** Sig. (2-tailed) Revenge Punishment Jealousy Punishment .247* N *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). .000 Part 3: Relationships between Personality Traits and Judgments of Culpability and Punishment HEXACO Honesty Correlated with Culpability Correlations HEX Honesty HEX Honesty Pearson Correlation GreedCulpability 1 .192 .203* .040 .044 .055 .043 100 100 100 100 100 Pearson Correlation .206* 1 .369** .505** .547** Sig. (2-tailed) .040 .000 .000 .000 N 100 102 102 102 102 Pearson Correlation .202* .369** 1 .500** .445** Sig. (2-tailed) .044 .000 .000 .000 100 102 102 102 102 Pearson Correlation .192 .505** .500** 1 .402** Sig. (2-tailed) .055 .000 .000 100 102 102 102 102 Pearson Correlation .203* .547** .445** .402** 1 Sig. (2-tailed) .043 .000 .000 .000 100 102 102 102 N Jealousy Culpability N Military Culpability MilitaryCulpability .202* N Revenge Culpability JealousyCulpability .206* Sig. (2-tailed) Greed Culpability RevengeCulpability N *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). .000 102 HEXACO Honesty, Emotionality, Extraversion & Conscientiousness Correlated with Punishment HEX Honesty HEX Honesty Pearson Correlation HEX Emotionality 1 Sig. (2-tailed) N HEX Emotionality Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N HEX Extraversion .011 .046 100 100 100 1 -.212* .022 .034 .829 .506 100 100 1 -.046 .011 .034 100 100 100 100 Pearson Correlation .200* .022 -.046 1 Sig. (2-tailed) .046 .829 .647 100 100 100 100 Pearson Correlation .201* .233* -.090 .103 Sig. (2-tailed) .045 .019 .371 .308 100 100 100 100 Pearson Correlation .234* .211* -.047 .286** Sig. (2-tailed) .019 .035 .641 .004 100 100 100 100 Pearson Correlation .168 .224* -.118 -.005 Sig. (2-tailed) .094 .025 .243 .960 100 100 100 100 .266** .279** -.211* .132 .008 .005 .036 .191 99 99 99 99 Pearson Correlation N N Military Punishment .506 -.212* N Jealousy Punishment .200* 100 N Revenge Punishment -.067 -.254* N Greed Punishment -.067 HEX Conscientiousness -.254* 100 Sig. (2-tailed) HEX Conscientiousness 100 HEX Extraversion Pearson Correlation (2-tailed) *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05Sig. level (2-tailed). N level (2-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 .647 Conclusion The present study has provided compelling evidence suggesting that the motivation behind a crime affects one’s perception of the perpetrator, as well as the manner in which they should be dealt. It has also demonstrated that judgments of punishment are closely aligned with assessments of culpability of the perpetrator. Interestingly, the results suggest that homicides motivated by jealousy and greed should merit stronger punishment than similar crimes motivated by revenge or in the course of military engagement. Furthermore, it has demonstrated that the sixth factor added to the traditional Big Five personality factor model by the HEXACO inventory—namely, HonestyHumility—is a strong predictor of such judgments. References Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. The HEXACO-60: A short measure of the major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(4), 340345. doi: 10.1080/00223890902935878 Darrick, J., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Development and validation of the basic empathy scale. Journal of Adolescence, 29(4), 589-611. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.010 Hessick, C. B. (2006). Motive’s role in criminal punishment. Southern California Law Review, 80(1). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=921111 Malle, B. F., Guglielmo, S., & Monroe, A. E. (2012). Moral, cognitive, and social: The nature of blame. In J. Forgas, K. Fiedler, and C. Sedikides (Eds.), Social thinking and interpersonal behaviour (311-329). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. Malle, B. F., Guglielmo, S., & Monroe, A. E. (2014). A theory of blame. Psychological Inquiry, 25(2), 147-186. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.877340 Nadler, J., & McDonnel, M. (2011). Moral character, motive, and psychology of blame. Cornell Law Review, 97(2), 255-304. 14 Q. B. D. 273 (1884). In S. H. Kadish and S. J. Schulhofer (Eds.), Criminal law and its processes (7th ed., 135-140).