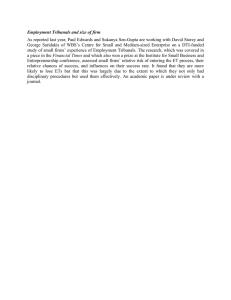

Academy of Management Perspectives Behind the Scenes: Intermediary organizations that facilitate science commercialization through entrepreneurship Journal: Manuscript ID Document Type: Keywords: Academy of Management Perspectives AMP-2016-0133.R3 Symposium Entrepreneurship (General) < Entrepreneurship < Topic Areas, Venture capital < Entrepreneurship < Topic Areas, Innovation Processes < Technology and Innovation Management < Topic Areas Page 1 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Behind the Scenes: Intermediary organizations that facilitate science commercialization through entrepreneurship Paige Clayton University of North Carolina clayton3@live.unc.edu Maryann Feldman University of North Carolina maryann.feldman@unc.edu Nichola Lowe University of North Carolina nlowe@email.unc.edu Acknowledgements: The National Science Foundation and the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation provided funding. 1 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 2 of 60 Abstract: Lacking resources to commercialize science, entrepreneurs rely on intermediary organizations often within their local ecosystems. This paper seeks to improve our understanding of how intermediaries operate to advance the commercialization of science by providing a set of specialized services. We review five intermediaries commonly mentioned in the ecosystem literature: university technology transfer offices; professional service firms; networking, connecting and assisting organizations; incubators, accelerators, and coworking spaces; and financing entities—including venture capital, public financing, angel financing and crowdsourcing. Specifically, we explore how these various intermediaries function and provide complementary and related services in support of scientific commercialization through entrepreneurship. After defining intermediation, we review the literature on each organization type, providing a definition and considering the contribution of the intermediary and the related policy implications. Each section concludes with suggestions for additional research. Keywords: intermediaries; science commercialization; scientific entrepreneurship; entrepreneurial ecosystem; entrepreneurial support organization. 2 Page 3 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives I. Introduction A successful theater performance requires a large support cast working behind the scenes, without which the show would not go on. Just as the audience focuses their attention on the dramatic action happening on stage, the commercialization of science tends to orient its gaze toward the innovative technology and its enabling star, the entrepreneur. But as with theater, diverse entities work behind the scenes to support the necessary processes of founding, managing and scaling a new scientific venture. In the commercialization of science, the least visible players are intermediary organizations — entities that operate in the void between the scientific discovery and the ultimate realization of value from commercialization, providing specialized services and access to equipment and resources beyond the reach of startup firms. Although these support organizations have a long history in helping disseminate information important to technology innovation, they are often treated as tangential to the study of science-based entrepreneurship (Howells, 2006). Yet varying access to these background supports can have a profound effect on entrepreneurial performance, as well as help sustain innovative activities within a regional economy (Cooke, Uranga, & Etxebarria, 1997). Academic interest in entrepreneurial ecosystems creates an opportunity to shine the spotlight on these behind the scenes organizations. By definition, ecosystems are “a set of interconnected entrepreneurial actors, institutions, entrepreneurial organizations and entrepreneurial processes which formally and informally coalesce to connect, mediate and govern the performance within the entrepreneurial environment,” (Mason & Brown, 2014, pp. 5). Thus, the nascent ecosystem literature makes room for a variety of innovation- 3 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 4 of 60 supporting intermediaries, including: nonprofit, private, and public organizations, as well as universities, incubators, entrepreneurial support organizations, professional service providers and venture capitalists (Isenberg, 2011; Mason & Brown, 2014; Auerswald, 2015; Bell-Masterson & Stangler, 2015; Mack & Mayer, 2015; Stam, 2015). The ecosystem model also suggests an organic and fluid relationship between intermediaries that coevolve in a place. However, in order to fully appreciate the synergistic effects of this relational dynamic, we first need to recognize the contribution each intermediary makes to this science commercialization ecosystem. While each type of intermediary offers the potential to bring unique—yet complementary—services and supports to a regional ecosystem, there is also the potential for multiple intermediaries to coordinate, and even duplicate, efforts in order to address persistent innovation challenges or gaps. The first objective of this paper is to improve our understanding of intermediaries in the commercialization of science. We limit our review to five intermediaries that support science commercialization commonly mentioned in the ecosystem literature: university technology transfer offices; professional service firms; networking, connecting and assisting organizations; incubators, accelerators, and coworking spaces; and financing entities—including venture capital, public financing, angel financing and crowdsourcing. Specifically, we explore how intermediaries operate in the context of scientific entrepreneurship by providing a set of specialized services to advance the commercialization of science. What unites these various intermediaries is their function and provision of both complementary and related services in support of scientific commercialization through entrepreneurship. After a brief framing of intermediation, we review the literature on each organization type in turn, providing a definition and 4 Page 5 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives considering the contribution of the intermediary and the related policy implications. Each section concludes with suggestions for additional research. II. Intermediaries Inside and Out Consideration of intermediaries adds a new theoretical dimension to studies on the commercialization of science. The Bush (1945) linear model argued that commercialization could be left entirely to the private sector if government supported upstream research (Hart, 1998). Stokes (1997) however questioned this division of labor arguing that interactions between public and private sector actors are often essential for bringing scientific discoveries to market. Adding to the discussion, Branscomb and Auerswald (2002) used the colorful metaphor “valley of death” to not only explain a frequent failure with science-based commercialization, but also to recognize the need for intervention to bridge these noted gaps. As this suggests, the ability to commercialize science depends on complex, dynamic and adaptive responses and relationships among private, quasi-public and public sector organizations. The concept of systems of innovation has been used to capture the relational dimensions and characteristics of environments that support knowledge creation and enhance innovation (Edquist, 1997). Systems of innovation are most succinctly defined as “the set of institutions whose interactions determine the innovative performance...of national firms,” (Nelson & Rosenberg, 1993: pp. 4-5). Yet the innovation system approach often assumes homogeneity within a single country, when significant regional differences within countries suggest that innovation is more often a subnational phenomenon. 5 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 6 of 60 Recent work by several European scholars has attempted to expand the Triple Helix model to include intermediaries that operate between universities, industry and government in several European contexts (Fernández-Esquinas et al., 2016; Suvinen et al., 2010; Todeva, 2013). While this work attempts to make the role of intermediaries more central, and uncovers the specific challenges of intermediation between the tripartite partners with differing goals, the theory is limited by its singular focus on universityindustry-government links. In contrast, the ecosystem concept, which originated with practitioners in the mid1990s (Autio & Thomas, 2014), recognizes the micro-geography of innovation and thus captures the diverse mix of locally-embedded support organizations that contribute to innovation. The modern concept of an innovation ecosystem is rooted in the earlier literature on systems of innovation and builds upon endogenous growth theory (Romer, 1990). New Growth Theory puts knowledge creation at the center of models of economic growth, while resonating with observations of the dynamic intra-regional social relations described as part of late 19th century Marshallian industrial districts. Increased interest in capturing the sub-national geography of innovation suggests an opportunity to look closely at the intermediary organizations that contribute to the vital health of a regional innovation ecosystem. It has long been recognized that innovative firms must be able to access, acquire, assimilate and exploit external knowledge to develop and sustain competitive advantage (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002). Yet firms, especially small entrepreneurial firms, rarely innovate in isolation. Networking with other firms often aids in the transmission of tacit and highly complex knowledge across firm boundaries, where 6 Page 7 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives vertical integration is inefficient and knowledge cannot be easily priced (Powell, 1990). Equally important, however, is access to other mediating agents and intermediary organizations that act as boundary spanners to help facilitate network formation among firms, while also extending essential resources, services, and guidance in support of innovation and the transfer of tacit and explicit knowledge (Howells, 2006; Wright et al., 2008). Intermediaries are especially important for science-based entrepreneurial firms given high barriers to commercializing scientific knowledge. At a general level, intermediary organizations support innovation by directly engaging with individual establishments through the provision of services and access to resources that can enhance business development or expedite technology commercialization. More specifically, intermediaries work with science-based entrepreneurs to overcome information and resource asymmetries by providing specialized information about: intellectual property protection, the navigation of clinical trials in the life sciences, and the negotiation of technical standards for firms innovating in information, internet, and equipment technologies. Some intermediaries offer specialized services that help entrepreneurs refine their ideas and business plans, reducing the transaction costs of engaging in commercialization activity. McEvily and Zaheer (1999) find that the development of new capabilities is stronger in firms with ties to regional intermediaries. Intermediaries can also help firms resolve financial constraints either directly, through subsidies, or indirectly, by making introductions to other sources of finance. Intermediaries also play an essential coordinating role, forging networks and partnerships across the science-based business community and introducing nascent 7 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 8 of 60 entrepreneurs to more established and influential business leaders, mentors, or partners. In this regard, intermediaries do not just address innovation gaps at the individual firm level. They also contribute to agglomeration economies by shaping and reshaping relational dynamics within and across the regional economy, through the creation of an industry commons (Berger, 2013). Intermediaries diffuse knowledge across firms and supply chains, thus providing a mechanism to give greater material substance to the concept of knowledge spillovers. While Marshall notes that the “secrets of the industry are in the air”, these intermediate support organizations provide channels for air circulation. Corredoira and McDermott (2014) support these findings, suggesting that intermediaries play an invaluable role in filling structural holes that separate firms, allowing for the fluid movement of knowledge. Their geographic concentration can also contribute to greater regional specialization, thereby helping to motivate new product and firm development (Feldman & Kogler, 2010). It is important to consider the possibility of negative externalities from the networking role of intermediaries. Pahnke et al. (2015) find evidence of competitive information leakage across shared intermediaries. Specifically, when firms are indirectly linked because they share the same intermediary (e.g., a VC firm), information may accidentally be leaked to a competitor and hinder—rather than support— innovation. This suggests that there are important qualitative differences in the ways that intermediaries operate. Innovation is clearly a high-risk undertaking, not simply for entrepreneurial firms that seek to transform novel ideas into society-enhancing solutions and marketable products, but also for the regions in which these innovative firms are embedded. In this regard, it is important to also recognize a third, yet often obscured contribution of regional 8 Page 9 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives intermediaries. An intermediary can reach well beyond the business community to support and sustain regional innovation and science commercialization through their on-going interaction with other intermediaries. This is the essential idea behind innovation systems or ecosystems: the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Intermediaries have been known to join forces in order to shape and inform policy action and regional strategy, even engaging in forms of collective action to amass political support in order to advance policy goals and capacity building (Feldman & Lowe, 2017). But equally, intermediaries align efforts in order to shape the types of scientific discoveries that get commercialized by local entrepreneurs, and in ways that often reflect the unique social, environmental or technological challenges facing residents in their region (Owen-Smith & Powell, 2006). In this respect, intermediaries are not only well-poised to address some of the emergent gaps in U.S. federal science policy, but they also provide a resource for guiding policy in support of science commercialization and regional economic development. Table 1. Intermediary Definitions and Roles in Scientific Entrepreneurship Here III. Methodology With this potential contribution in mind, we began this analysis with an examination of the ecosystem literature. Admittedly the ecosystem concept encompasses a variety of culture, social, and symbolic conditions that augment the contribution of more formal support institutions (Stam, 2015). Still, as Spigel (2015) notes, formal institutions within an ecosystem are tangible entities that are most easily influenced by policy. We focus on five 9 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 10 of 60 tangible, physical entities most commonly featured in ecosystem analysis: university technology licensing offices; professional service firms; workspace providers, including incubators, accelerators, and coworking spaces; organizations that provide networking and programmatic assistance; and financing entities, including venture capital, angel investment, public funding, and crowdsourcing. Table 1 defines each intermediary and provides examples of their role in scientific entrepreneurship. For each of these categories, we conducted an extensive literature search using a variety of keywords outlined in Appendix A. This produced a large cross-section of the literature. Scholarly journal articles were found through online searches of bibliographic databases such as: Web of Science, Google Scholar, and ProQuest Summon. In an effort to reduce bias in the results of searches, we specifically included highly cited as well as more recent articles. We also included articles from a range of journal rankings and disciplinary fields. Papers were included based on whether they contributed to the state of knowledge on intermediation or a specific intermediary organization. IV. University Technology Transfer and Licensing Offices The commercialization of academic science typically begins with university technology transfer or licensing offices (TTO) that work with businesses to license a university-created technology (Spigel, 2015; Stam, 2015). In the U.S., the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 formalized a process for the licensing of university inventions that resulted from government-funded research, although there was an historical precedent for university ownership (Mowery et al., 2004). Other countries have adopted policies similar to the U.S. system of university ownership or—alternatively—assert professors’ privilege so that the 10 Page 11 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives individual inventor retains ownership (Cunningham & Link, 2016; Huyghe et al., 2016). Many reviews consider the role of universities in the economy and highlight their role in ecosystems (D’Este & Patel, 2007; Etzkowitz et al., 2000; Rothaermel et al., 2007). Our focus, however, is limited to the specific role of TTOs as intermediary organizations that assist in the commercialization of science. It is worth noting that ideas with scientific value can also originate from government labs and from private firms, although there is less research on their commercialization efforts. For private firms, internal offices and legal counsel (rather than intermediaries) manage the licensing relationship (Kline, 2003; Maine, 2008). Technology transfer offices participate in markets for technology, defined as “transactions for the use, diffusion and creation of technology (or intellectual property),” (Arora et al., 2001, pp. 423). While firms of all sizes license technology, academic startups feature most prominently in scholarly work as they are seen to offer the possibility of greatest impact. Yet university technology transfer is characterized by highly skewed distributions, with the majority of offices failing to break even while other TTOs have big hits and enjoy strong revenue flows (Feller and Feldman, 2010). Siegel and Wright (2015a) argue that TTOs overcome three main challenges: first, they provide faculty incentives to disclose inventions and engage in the commercialization process; second, TTOs maintain researcher involvement in the development process, and; third, they provide information about the value of technology. Of course, faculty can bypass the formal TTO process by patenting directly with industry (Siegel et al., 2004). While some critics complain that licensing may diminish the traditional strength of informal university knowledge spillovers, Thursby and Thursby (2002) provide evidence that this is not the 11 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 12 of 60 case. Wright et al. (2008) find, however, that TTOs better intermediate the transfer of explicit rather than tacit knowledge in a study of TTOs in the U.K., Belgium, Germany, and Sweden. The organization of the TTO as well as the level of resources committed by the university are important to the capacity to commercialize technology (Bercovitz et al., 2001; Siegel et al., 2003). Thursby and Kemp (2002) found that private universities tend to be more efficient in licensing than public universities, while universities with a medical school are less efficient in licensing. O’Shea et al. (2005) found that the number of startups a university is able to generate is related to: past university TTO success, faculty quality, the size and source of research funding, and the amount of resources devoted to TTO staff. Markman et al. (2005) find a positive relationship between the speed with which the TTO processes new invention reports and the creation of startups. Importantly, based on the case of Belgium’s K.U. Leuven TTO, Debackere and Veugelers (2005) argue that wellmanaged and structured TTOs reduce information asymmetries between industry and university, fostering industry-university linkages that are lacking in the European context and cause the “European paradox” of high levels of scientific expertise, with low contributions to industry. The finding by Huyghe et al. (2016) that more than half of surveyed pre- and postdoctoral researchers at 24 European universities were completely unaware of their university’s tech transfer operations, however, is not an encouraging figure. TTOs use various mechanisms to improve the commercialization of academic science, including equity and uniform startup licenses, to educational support programs, and incubators. Universities started using equity in lieu of licensing fees to encourage new 12 Page 13 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives firm formation (Feldman et al., 2002). Di Gregorio and Shane (2003) found that TTO policies, rather than capital market constraints, impact the number of new ventures created: more startups are formed when TTOs make equity investments. Many types of licensing agreements are used by TTOs, with new express licenses recently becoming popular (Rector & Thursby, 2016). The commercialization of academic science now involves more stakeholders, especially at the regional level. Furthermore, the methods of commercialization have expanded, e.g., accelerators and business plan competitions (Siegel & Wright, 2015b). If the local TTO is not effectively engaged, other intermediaries are likely to gain importance in the ecosystem. If TTOs serve an important purpose, then the faculty that commercialize on their own (either through professor privilege or who choose to circumvent the process) should find a substitute intermediary. And even when the university TTO is well resourced and has a strong history, other intermediaries may assist commercialization activity. V. Physical Space: Incubators, Accelerators, and Coworking Spaces The commercialization of science requires physical workspace, laboratory space, clean rooms and advanced equipment. Incubators, accelerators, and coworking spaces provide entrepreneurs access to physical facilities at below market rates, and with preferential terms. Moreover, the co-location of physical facilities allows for the circulation of ideas. Incubators, accelerators, and coworking spaces may be affiliated with universities or alternatively operate as public, for-profit, or nonprofit entities. Mian et al. (2016) calls for the development of a field of study called Technology Business Incubation (TBI) to further define these intermediaries’ contributions. Perhaps what is most interesting is that 13 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 14 of 60 while incubators have been in existence over half a century, accelerators are a much newer phenomenon, and new organizational forms (such as coworking spaces) are proliferating. In general, the trend is for physical space providers to add services that aid commercialization, reflecting the political and social context surrounding these organizations (Phan et al., 2005). Incubators Incubators, as the name implies, attempt to support early stage firms to a point where they hatch or become viable entities. The expectation is that successfully incubated firms can exit in a strategic business position (Aernoudt, 2004). Though first appearing in the 1950s, incubators began to grow in number in the U.S. during the 1980s for reasons including: the passing of Bayh-Dole, expansion of IP rights in the U.S., and newfound profits from biotechnology commercialization—all factors driven by the potential for commercializing science (Hackett & Dilts, 2004). The rise of European science parks occurred largely as a result of Triple Helix partnerships designed to replicate U.S. successes (Colombo & Delmastro, 2002). Categorizing the organizational forms and management practices of incubators has been a vexing problem and is one reason why there is little conclusive empirical research. Bruneel et al. (2012) present an evolutionary process that characterizes generations of incubators, with each augmenting the value proposition. First generation incubators focused only on offering affordable space, while second generation incubators added knowledge-based business support services. Third generation incubators began to add networking support and serve earlier stage companies, focusing more on selection and 14 Page 15 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives quicker tenant turnover, in an effort to make profits. While the earliest incubators were publicly financed, for-profit and corporate incubators emerged, with incumbent companies offering incubation as a means to generate new sources of revenue (Becker & Gassman, 2006). Incubators can also be categorized according to their objectives: mixed type incubators serve all technologies and types of firms, while economic development incubators aim to leverage local activities to create employment opportunities (Aernoudt, 2004). A third category, technology incubators, typically focus on specific sectors (often aligned with cluster development strategies) and offer access to shared specialized resources, such as testing facilities or chemical formularies that are especially important for the commercialization of science. In a study of 13 specialized and 13 diversified German business incubators, Schwartz and Hornych (2010) find a firm's industry rather than incubator specialization better explains the likelihood of firm linkages to academic institutions, and find no difference in internal network patterns between incubator types. This heterogeneity of mission, organizational form and practice complicates impact assessments (Mian, 1996, 1997; Di Gregorio & Shane, 2003; Bergek & Norman, 2008; Hackett & Dilts, 2004, 2008; Mian et al., 2016; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2014). Not surprisingly, the effectiveness of incubator participation on the commercialization outcomes of individual firms also varies. Schwartz (2013) found incubated firms do not have a statistically significantly higher chance of survival than nonincubated firms. In contrast, Lewis et al. (2011) used discriminant analysis and found business incubation positively impacts firm outcomes. Incubator quality is more predictive of outcomes than incubator size, age, or regional capacity for entrepreneurship. They also 15 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 16 of 60 found most top-performing incubators tend to: be nonprofit, have government support, have larger budgets, and exhibit similar management practices. Furthermore, incubator success is correlated with having incubator graduates and technology transfer specialists on the incubator’s board. In interesting new research analyzing the roles of business incubators in emerging markets, Dutt et al. (2016) find these incubators may operate as “open system intermediaries” to support market development as well as to support individual business development. These contrast to “closed system intermediaries,” as open system intermediaries “seek to create benefits for parties beyond a well-identified set of participating actors,” (pp. 819). More research on intermediaries in these emerging economies is warranted. The number of incubators is ever increasing, suggesting an opportunity for evidence-based research to guide operations. Contradictory results may reflect the wide range of services offered by incubators from subsidized real estate to intensively managed, supportive environments. This suggests the possibility of developing a matrix of incubator characteristics matched against the local characteristics of entrepreneurs and the existence of other support organizations in the region. Accelerators Although accelerators have been described as a “new generation incubator model” (Pauwels et al., 2015, pp. 13), they differ from incubators on a number of variables— including: duration, business model, selection, and mentorship—among others (Cohen, 2013). Firms are typically provided with a small investment in return for an equity share. 16 Page 17 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Selection into accelerators is highly competitive, which sends a quality signal to outside investors (Kim & Wagman, 2014). Accelerators make extensive use of seminars for education about entrepreneurship. Furthermore, mentorship is intense in accelerators and a multitude of relationships can exist between the accelerator and the startup, including: direct investment, help with finding additional investment, and partnering in pilot production and distribution (Kohler, 2016). Accelerators also stress finding the value proposition for the customer, which can be especially beneficial for scientists turned entrepreneurs who tend to focus on the scientific aspects of their firm. Moreover, many accelerators focus on ideas, projects or ventures before the formation of a company. After an intense three to six-month program, entrepreneurs have gained information about the viability of their project—the science may be strong, but if a market does not yet exist then it is not a good opportunity. Accelerator funders are more like venture capitalists in that they invest in a group of firms, while only expecting to receive large returns on just a few ventures. Therefore, they will accept earlier investments overall, which is important for commercializing science. Hallen et al. (2014) study the impact of accelerators based on the time it takes ventures to reach certain milestones, such as the first round of VC. They find mixed results using a Cox proportional hazard model on a matched set comparison of accelerated and nonaccelerated ventures. They find no difference between accelerated and non-accelerated firms, however firms in some specific accelerators did realize a faster time to milestones than did other accelerators. Hallen et al. (2014) argue these results are indicative of the difficulties in the acceleration process. Empirical work is needed to shed further light on 17 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 18 of 60 acceleration processes and outcomes, as data on accelerators becomes more widely available. Recent studies find accelerators do have an effect on early firm outcomes. Smith and Hannigan (2015) use hazard analysis to compare startup exits and follow-on funding outcomes between accelerated and angel-funded firms. With data from two top accelerators and 19 top angel funders, they find accelerated ventures are more likely to exit by acquisition, and at an earlier date, than angel-funded firms. Accelerator firms are also more likely to receive a first round of VC funding earlier than angel-funded firms, and this earlier date is around the time of the accelerator’s ‘demo day’. Smith and Hannigan (2015) argue these findings are the result of differences between the processes of angel versus accelerator investing, and the ways in which angels and accelerator managers realize returns. The fact that accelerator operators invest in cohorts and spend more time nurturing and mentoring the firms could be such an explanation. The presence of an accelerator may signal a strong or growing entrepreneurial ecosystem. Fehder and Hochberg (2014) use difference-in-differences analysis to analyze the impact of accelerators on entrepreneurial ecosystems. They find that startups located in MSAs with an accelerator receive more financing whether or not they participated in the accelerator, and argue this indicates that accelerators have an impact on ecosystem strength. The role of accelerators in ecosystems and compared to other workspace provision models, however, would benefit from greater theoretical and empirical development. Coworking Spaces 18 Page 19 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Coworking spaces—a low rent, alternative workspace purported to offer a fun and informal atmosphere—are another new phenomenon in the workspace intermediary field. Coworking spaces are distinguished from earlier shared office facilities by their emphasis on social interactions, aesthetic design and management by cashed out entrepreneurs and potential investors (Waters-Lynch et al., 2016). They are found in hotspots of activity and range from small operations to national organizations—such as WeWorks—and large firms—such as Microsoft and Google. Incubators and accelerators have evolved to offer coworking spaces, but Moriset (2014) questions their future, arguing the spaces neither create much profit for operators, nor add much value to occupants. There are three types of coworking space users: freelancers, microbusinesses, and people working for themselves or for companies external to the space (Parrino, 2015). Knowledge exchange through collaborative relationships only occurs when the coworking organization encourages such collaboration—co-location alone does not foster collaborative relationships. Data from an online coworking magazine, Deskmag, indicates entrepreneurs are present and active users of coworking spaces; approximately, 20% of coworkers are entrepreneurs that employ other workers (Foertsch, 2011). Research on the contribution of coworking spaces to science entrepreneurship is limited thus far. A case analysis in South Wales found that coworking spaces support entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial activities through networking, peer mentoring, and allowing easier access to forms of capital, among other things; but, this study has limited generalizability (Fuzi et al., 2015). Waters-Lynch et al. (2016) argue Schumpeterian economic theory is a useful theoretical lens through which coworking may be studied to understand how it contributes to innovation. For scientists working on an idea, a third- 19 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 20 of 60 place to go to meet with like-minded people may be an important first step. Future empirical work will be important for this field. VI. Professional Service Providers Professional service firms (PSF) aid in the commercialization of science by vetting proposals for new companies and connecting founders to a wider pool of resources, networks, and entrepreneurial support. These service professionals have access to specialized knowledge, are usually embedded in an existing entrepreneurial community, and can serve as network bridges for new entrepreneurs, thus helping reduce transaction and search costs (Zhang & Li, 2010). Extending the entrepreneurial ecosystem concept, Stam (2015) considers PSFs to be vital “feeders” into that system. Hayter (2016) found service providers are especially important to academic entrepreneurs as they provide information related to law and accounting, as well as services such as product testing that might not be accessible to them through their established academic networks. Professional service firms have not been studied widely in the management literature (Empson et al., 2015). This reflects difficulty in identifying which ancillary firms qualify as technology intermediaries. Von Nordenflycht (2010) presents a taxonomy based on three defining features: knowledge intensity, low capital intensity, and high degree of professionalization. Knowledge intensity, the high degree of knowledge specialization, is the most important defining feature. The higher the degree of knowledge specialization, the more important the service is to the entrepreneur. The majority of studies focus on law firms. Gilson’s (1984) seminal work found that Silicon Valley attorneys act as transaction cost engineers, reducing costs of engaging in 20 Page 21 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives commercialization. In a study of prospective entrepreneurs, Shane (2001) found local attorneys provide initial advice on patent protections and scope affecting the decision to start a company. Accountants and investment bankers provide a similar function reducing the impact of information market failures on startups (Gilson, 1984). Suchman and Cahill (1996) found Silicon Valley business attorneys further define local business norms and integrate norms into the legal and business community. Suchman (2000) found Silicon Valley attorneys function as business counselors, dealmakers, gatekeepers, proselytizers, and matchmakers. As dealmakers, lawyers link startups to other firms, such as VC. As gatekeepers, they selectively connect startups to other members of their networks. As proselytizers, they use their influence to educate startups on business norms, further solidifying norms. As matchmakers, attorneys sort and match clients and resources. These roles shape the broader community. Cable (2014) argues this model of startup lawyering has grown with the proliferation of entrepreneurship as an economic development strategy. Originating in Silicon Valley, the practice has several distinctive features as attorneys set contract standards and defer initial payments in lieu of equity, believing that greater return will follow. In an investigation of the spatial patterns of semiconductor firms that recently had their initial public offering, Patton and Kenney (2005) found that legal counsel used by entrepreneurs is always proximate to startup activity, followed by investment bankers, venture capital, and finally independent directors. While locational patterns differ across industries, a subsequent paper using the same data found that attorney startup services remain highly local (Kenney & Patton, 2005). 21 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 22 of 60 Gompers and Lerner (2010) argue real estate brokers and managers familiar with equity investing also reduce transaction costs of obtaining finance. Accountants and investment bankers provide a similar function reducing the impact of market failures on startups (Gilson, 1984). Zhang and Li (2010) analyzed the impact of startup network ties to PSFs on production innovation in a study of 202 firms in a Chinese technology cluster. They found new ventures’ networks with technology service firms, law firms, and accounting firms have a positive impact on firm product innovation. The sparse and disconnected nature of the literature outlined here shows ample room for continued research on the role of PSFs as intermediaries in the entrepreneurship and technology commercialization process. The literature lacks a theoretically constructed conceptualization of the impact of attorneys, accountants, insurance agents, and other service providers, on technology commercialization. Additional analysis at a regional scale will be most useful as previous studies show service providers mostly operate at a local level. Finally, an important, yet unanswered, question raised by Friedman et al. (1989) is whether Silicon Valley attorneys help the high technology industry grow, or whether— conversely—the high technology industry led to growth in the local legal sector. Perhaps it is less a case of determining directionality, and more a future research opportunity for studying positive feedback and mutual reinforcement. VII. Networking, Connecting and Assisting Organizations Public, quasi-public and nonprofit programs frequently step in to support scientific entrepreneurship. These public service organizations have limited expectation for direct financial gain, but rather a greater focus on the public outcomes of economic growth 22 Page 23 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives through the promotion of startups. They serve networking support roles for entrepreneurs, coordinating local organizations and programs by bringing together public and private entities, and serve agenda-setting roles for policy and practice. Motivated to serve a public purpose, these organizations exist to address network failures (Schrank & Whitford, 2009). One example of such an organization is the North Carolina Biotechnology Center (herein, “the Biotech Center”), established by the North Carolina legislature in 1981 as a nonprofit 501c3, with the majority of its budget derived from annual state appropriations (Feldman & Lowe, 2011). As a quasi-public nonprofit, the Biotech Center has the option to secure additional funding, including federal research grants. This nonprofit structure has enabled the Biotech Center to position itself as less partisan, and thus retain state support even during changing political environments (Lowe & Feldman, 2015). Another example of a successful quasi-public, coordinating, and networking program is the San Diego CONNECT program. This intermediary was founded in 1985 as a bottom-up effort of entrepreneurs, supported by economic development officials, to connect industry to academia and advance local entrepreneurship and the commercialization of academic science (Kim & Jeong, 2014; Walcott, 2002). Disconnecting from the university may have allowed CONNECT to reach a broader base of entrepreneurs to assist. Not-for-profit organizations with more limited government involvement also offer a portfolio of topical programs to respond to local needs and contribute to the commercialization of science through entrepreneurship. One example is the nonprofit Council for Entrepreneurial Development (CED), one of the nation’s first membership organizations dedicated to new firm support by providing: networking assistance, mentorship, entrepreneurial education and training, and identification of capital sources. 23 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 24 of 60 Research finds such organizations efforts fruitful. Cumming and Fischer’s study (2012) of a one-stop Innovation Synergy Center in Ontario, finds that publicly-provided business advisory services positively affect entrepreneurial outcomes. Both nonprofit and quasi-public programs can operate at multiple scales. Nonprofits such as SCORE and America’s Small Business Development Centers (SBDC) have a national reach and receive federal funding from the Small Business Administration (SBA), though operate a decentralized network of local programs. SCORE offers entrepreneur training workshops and mentoring through over 300 chapters. SBDC is an entrepreneur and small business assistance network that offers training and mentoring through partnerships with universities and state economic development agencies. Chrisman et al. (2005) found the time entrepreneurs spent in “guided preparation” with an outside advisor at SBDCs prior to starting a company was associated with increased startup performance, including better employment and sales outcomes. Still, the time spent had diminishing marginal returns. Yusuf (2010) argues that startup assistance programs like these may not have an immediate effect, but often help support entrepreneurs’ latent, rather than perceived, needs. Local programs to support entrepreneurship also exist, which may be directed by a higher level of government. In their case study of a Midwest region Feldman and Lanahan (2010) find that firms pursue state and local funding programs more often than federal programs. They also find local innovation programs have difficulty coordinating activities and practices, and argue for the creation of bottom-up regional coordinating bodies. As nonprofit and quasi-public structures and governing bodies continue to proliferate, there is a need for greater research on these organizations, their programs and 24 Page 25 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives their impact. Multiple points of contact, however, make evaluations of single organizations more difficult. There is an opportunity for more empirical work on the interaction, sequencing and coordination of various forms of public and quasi-public support. VIII. Finance Providers Finance organizations are especially important intermediaries for supporting the commercialization of science through entrepreneurship. Without money, science and technology-based companies simply cannot grow. Kerr and Nanda (2015) review the literature on innovation finance and find that four features of the R&D process constrain finance. First, the innovation process is uncertain. Second, innovation’s returns are highly skewed. Third, information asymmetries between entrepreneurs and investors favor entrepreneurs. Fourth, new innovation-focused ventures often rely on intangible assets that can easily be lost if employees leave. The expenses for science based startups are higher than average due to the costs of: labs and clean workspaces, highly skilled employees, insurance, consulting services, and the need to protect intellectual property. This list of expenses could easily be substantially increased, depending on the technology. Thus, a variety of entrepreneurial funding sources have emerged to help companies commercialize. These sources entail varying costs to the entrepreneur, and provide different degrees of value-added services. For example, both banks and VCs monitor investee firms, but VCs also offer value-adding services (Fraser et al., 2015). Funding sources are typically characterized by ownership: public, nonprofit, and private. Funding organizations may be local or operate at a national level. Furthermore, universities take equity in academic startups in lieu of licensing fees, which provides 25 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 26 of 60 legitimacy for the startup and allows the university to share in any potential upside (Feldman et al., 2002). Entrepreneurs typically initially bootstrap their companies, obtaining funding from what is known as the three F’s—friends, family, and fools. Other financial intermediaries screen startups, provide contractual agreements, and monitor investments on behalf of investors (Berger & Udell, 1998). We look at financial intermediation in terms of its impact on commercialization outcomes, rather than just in terms of financial outcomes for investors, and to investigate the nonpecuniary roles of financial intermediaries. Venture Capital Defined as “the professional asset management activity that invests funds raised from institutional investors, or wealthy individuals, into promising new ventures with a high growth potential,” (Da Rin et al., 2012), VC firms operate as partnerships that raise money from institutional and individual investors. They may be corporate, bank-owned, private or government-sponsored. Private-sponsored VC is less common in European countries than in the U.S. In Asian countries, however, VCs do not have the same relationships with universities as in the U.S.: VC often invest in earlier stages in Asia than in the U.S. (see Kenney et al. 2002 for a review of VC in Asia). VC funding is the most extensively studied form of entrepreneurial finance and is noted to have an aggressive management model that facilitates the commercialization of science. Samila and Sorenson (2010, pp. 1358) argue, “venture capital supports the development of these [innovative] ideas and helps to train and encourage a community of entrepreneurs capable of bringing 26 Page 27 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives those ideas to market,” making clear the contribution of VC as a commercialization intermediary. Venture capitalists use a multistage financing approach that provides funding in tranches. This allows VC to stop funding if specific benchmarks are not met, or if it becomes apparent that the firm is not going to succeed (Kerr, Nanda & Rhodes-Kropf, 2014). Public research funding and VC are complementary and result in more innovative activity, as measured by patents and startups, when a region has a greater amount of VC (Samila & Sorenson, 2010). The ability of VC investment to stimulate innovation also depends on characteristics of the VC firm (Kortum & Lerner, 2000). Hsu (2006) finds VC-funded firms are more likely to engage in cooperative commercialization strategies such as strategic alliances, and more likely to have an initial public offering (IPO) than non-VC funded firms. These results were intensified when well known VCs provided funding. Hsu (2004) finds that startups will pay more in terms of equity for investments from VC firms with higher reputations. VC networks are useful to startups (Cable & Shane, 1997), yet Wright et al. (2006) identify heterogeneity, as some VC have more social capital and involve themselves more deeply with the company. Cumming and Dai (2010) find VC investment decisions have a decidedly local focus. Over 50% of investments are made in firms located within 250 miles of the VC firm’s office. However, more reputable and well-networked VCs have a broader geographic reach. More local bias is present when VC is specialized in a technology industry and when investments are made in a greater number of rounds. Results show that local investments are more likely to have successful exits, which also has implications for how VCs add value to portfolio firms. Furthermore, the value-added effect of VC tends to vary depending on 27 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 28 of 60 where the VC firm is located. Pinch and Sunley (2009), for example, find VC in the Southampton, U.K. cluster are less effective as knowledge transfer agents than VC in leading high-tech clusters such as Silicon Valley. Cumming and Dai (2011) investigate the relation between VC fund size, and successful firm exit—finding fund size has a diminishing marginal return to startups. In a novel exploitation of exogenous variation in new airline routes, Bernstein et al. (2016) found that greater on-site involvement, particularly of the lead VC, increased innovation in firms along a number of dimensions; and interpreted these findings to indicate active monitoring by VC is, in fact, a valuable asset for funded firms. Wright et al. (2008, pp. 1209) argue, “venture capitalists and angels with specialist technological skills may act as intermediaries that provide access to customers and suppliers.” These connections may be especially important for technology based firms. Vanacker et al. (2013) investigate how VC adds value to startups compared to angel investors. They matched a sample of VC- and angel-backed firms to similar non-backed firms and used OLS regression to assess impact on performance measured by gross profits, finding both funding sources moderate the relationship between slack resources and firm performance compared to non-backed companies. Angel investors are associated with better use of human resources, while VC investment was associated with better financial and human resource use. The results indicate that startups’ efficiency in operations, such as commercialization, may benefit more from VC than angel investment. Furthermore, the VC effect is correlated with the equity share—greater VC ownership increases performance. The literature has also considered how VCs make investment decisions. Nanda and Rhodes-Kropf (2013) found that hot markets make VC investors more willing to 28 Page 29 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives experiment by investing in more radical innovations. Bottazzi et al. (2016) find trust levels affect VC decision-making and are a complement to contingent control contracts. Specifically, higher trust predicts the likelihood of an investment being made, meaning contracts are not used to overcome trust issues, but are used when trust exists. Further investigation into the characteristics of VC, which allow them to best act as local intermediaries and affect commercialization, would be useful. There is a need to consider the match between VC characteristics and firm characteristics and commercialization potential. Also, there is currently little research that considers how VC interacts with other ecosystem intermediaries and members. Angel Investors Angel investors are individual investors who invest in smaller amounts and at an earlier, riskier stage of startup development, which helps to provide proof of concept for scientific discoveries. The total amount of startup financing provided by angels is greater than the amount provided by VC (Wessner, 2002). Angels are often experienced entrepreneurs with technology expertise, and offer advice and mentoring for an indefinite amount of time (Cohen, 2013; Ibrahim, 2008). Beneficial for commercializing science, angels also have much longer time horizons than VC as they do not have to exit at some point on behalf of other investors, yet like VC they prefer to be located close to startups in which they invest (Berger & Udell, 1998; Sohl, 1999). Research on angel investment is still developing, constrained by a lack of data. Sohl (1999, pp. 106) describes angel investment as a “relatively invisible” venture capital market segment. Ibrahim (2008) observed a lack of interest by academics and media on 29 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 30 of 60 this group, even as this group has attributes, such as patience and eclectic interests, that make them good first investors in commercializing science. Ten years later this trend has reversed, but the difficulty of obtaining data from private angel investors makes empirical work challenging. Studying this less visible group requires innovative techniques. Kerr et al. (2014) used data obtained directly from organized angel groups in a regression discontinuity design to study the effect of angels on firm outcomes. Defining a discontinuity threshold as a level of critical interest shown in the company by angels, the results suggest that startups funded by two successful angel groups had a higher probability of survival or successful exit, and better employment outcomes than those rejected by the same groups. Bernstein et al. (2015) performed a randomized field experiment using the online “AngelList” investing platform to investigate how angel investors make investment decisions based on startup characteristics. The manipulation of emails alerting investors of new investment opportunities introduced exogenous variation into the information provided to potential investors, allowing identification of angels’ interest level. Interestingly, angel investors were more influenced by founding team composition than firm sales and the identities of other investors, reinforcing the idea that this class of investor may be important for commercializing science. Public Funding Public and quasi-public funding programs often extend financial support for commercializing science. Government has taken an active role in supporting science and innovation for over half a century, though direct public support for entrepreneurship is 30 Page 31 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives more recent. Public programs such as the U.S. Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, which provides highly competitive grants to develop technology for Federal Agencies, have operated since the 1980s. Such programs operate outside the U.S. as well. Aernoudt (2005) uses the case of a successful Belgian program to argue public coinvestment programs are an effective means to help angels spread risk. A long literature evaluates the impact of the SBIR program (Lanahan & Feldman, 2015, 2017; Lanahan, 2016; Lerner 1999; Link & Scott, 2010; Qian & Haynes, 2014), yet consensus on the program’s impact is elusive. An SBIR funded project faces a 50% probability of failing to produce a commercialized technology, though Link and Scott (2010) compellingly argue this an acceptable risk level for the federal government. Reinforcing this, Lerner (1999) found that firms with SBIR grants grew faster in sales and employment, and were more likely to receive subsequent VC investment than a matched set of firms without SBIR; results were stronger in high-technology industries and in regions with a higher concentration of VC. Furthermore, SBIR funding has a positive impact on patenting levels in small and medium sized nanotechnology firms (Kay et al., 2013). While U.S. states create their own entrepreneurship programs, they also leverage and augment national programs. Forty-two states have SBIR service assistance programs and 17 states have an SBIR matching grant (Lanahan & Feldman, 2015). Lanahan and Feldman (2017) provide evidence of the efficacy of such policies, finding that firms that receive an SBIR Phase I state match grant have a higher probability of receiving an SBIR Phase II grant, when awarded from the National Science Foundation. Finance is also available in the form of public VC. Pergelova and Angulo-Ruiz (2015) analyze the impact of U.S. government equity, loan and guarantee programs for 31 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 32 of 60 entrepreneurship, finding that guarantees and equity have a positive impact on firms’ competitive advantage and an indirect effect on profits. Public sources may offer less added-value to startups engaging in commercialization than private sources, though. Pierrakis and Saridakis (2017) find that U.K. firms receiving only public VC apply for less patents than those obtaining only private VC, attributing this divergence to public fund manager’s lack of expertise compared to private managers. Indirect public efforts are also seen through attempts to stimulate investments from private sources. Lerner (2002) argues government intervention, in the form of public VC, is justified when public investment can certify firm quality to other investors, and when technological spillover is possible. Several states have created investment programs, such as Connecticut Innovations, a quasi-public, state-funded venture capital fund founded in 1989 (Feldman & Kelley, 2002). Lerner (2002) warns, however that public VC programs can be inefficient and difficult to design. It is certainly true that many public financing programs are oriented towards capturing the benefits of science commercialization within their jurisdictions’ boundaries. Moreover, different levels of governments, national and local, have the capacity to design their own programs and experiment with different requirements and stipulations, which makes program evaluation difficult. Future research should continue to investigate the role public funding sources play in stimulating innovation and commercialization. Crowdfunding Crowdfunding is the newest—and least understood—practice in entrepreneurial finance, and is defined as: “the efforts by entrepreneurial individuals and groups – cultural, 32 Page 33 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives social, and for-profit – to fund their ventures by drawing on relatively small contributions from a relatively large number of individuals using the Internet, without standard financial intermediaries" (Mollick, 2014, pp. 2). Crowdfunding emerged after the 2008 recession— when bank finance became less available—and has become more structured with time, though equity crowdfunding standards are slow to develop in many countries (Bruton et al., 2015; Harrison, 2013). The 2012 JOBS Act legalized equity crowdfunding in the U.S. (Agrawal et al., 2014). Crowdfunding platforms allow individual or pooled investments in firms or projects, usually called campaigns (Bruton et al., 2015). The use of web-based platforms offers an opportunity to describe the science underlying a project and to reach a larger set of potential investors than possible through the angel funding model. Crowdfunding models also differ in how funders receive compensation. Donation models do not provide compensation for investors and usually benefit nonprofits or charities. Reward models offer gifts in return for investment. Pre-purchase models provide investors with the product in which they invested. In lending models, investors receive returns following typical borrow-lender relationships. Finally, equity models offer shares in profit, or ownership (Harrison, 2013). Current crowdfunding research is dominated by descriptive and case-based studies. Lehner et al. (2015) uncover broad, nonfinancial implications of crowdfunding using four campaign case studies, including crowdfunding’s ability to serve as an alternative distribution channel where funders act as pre-market testers and help with problem identification, quickening commercialization time. 33 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 34 of 60 Several crowdfunding studies use data from Kickstarter, a prominent reward-based platform. Frydrych et al. (2014) find certain signals impact how projects gain legitimacy, including founding team composition and the time to achieving funding goals. Stanko and Henard (2016) study innovation outcomes of successful Kickstarter campaigns and find that beyond funds generated, campaigns help creators with product feedback and idea sharing—important to commercialization. With surveys and data from over 200 Kickstarter firms they find the amount of subsequent innovation by campaigners is related to campaign features, such as how open the campaign is to external ideas, and how early in the development process the campaign began. These findings suggest that crowdfunding may provide an enhanced commercialization model. The geography of crowdfunding investment is of interest since its online basis should theoretically obviate geographic bias. Agrawal et al. (2011) find geography does not play a role in investment decisions once campaigners’ friends and family network is controlled for in estimation. Still, most campaigns are concentrated in geographic regions typically viewed as more entrepreneurial (Mollick, 2014), highlighting the need to consider crowdfunding as part of the regional innovation ecosystem. Though some entrepreneurial finance providers have been studied extensively, there is a need to understand the relationships and dependencies among finance sources. Learning how various sources impact the likelihood of receiving funding from different sources will provide important information to entrepreneurs seeking to commercialize scientific discoveries, and policy makers designing public finance programs. Better data is imperative to extending research on angel investing and crowdfunding. 34 Page 35 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives IX. Institutional Travels Popular accounts of innovation in regional economies often presume venture capital is the most essential institutional actor for supporting local entrepreneurship. But as Lerner (2009) notes in The Boulevard of Broken Dreams, the presence of VC is not sufficient to create an innovative local economy, and VC investment does not guarantee entrepreneurial firms will be successful. As this comprehensive survey illustrates, there are many other institutional actors in the mix, each adding additional and complementary services and supports. In some cases, these intermediaries focus on a particular segment of the local entrepreneurial community—the most focused of which are incubators, accelerators and coworking spaces, which only service those firms that secure residency in their facility. But others have a broader reach. University TTOs are on the front lines of technology intermediation. The ability of TTOs to accumulate stocks of human, network, and technological capital make them important players in ecosystems. However, not much is known about their actual potential for economic development and how policymakers might exploit their resources for broader goals. While the TTO literature is expansive, there are gaps in our understanding of the effectiveness and relationships of TTOs to other intermediaries in the ecosystem. Incubators, accelerators, and coworking spaces offer firms and entrepreneurs varying levels of support with one common feature—the provision of laboratory and/or workspace. While incubators have been studied the most closely of all three types, there is a need for more knowledge about incubation processes and effectiveness. The research on accelerators and coworking spaces is much newer. Empirical and theoretical work is 35 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 36 of 60 necessary to better understand how these organizations contribute to technology commercialization and startup outcomes. Another promising topic for future empirical research is professional services firms. Though these firms are not as glamourized as accelerators and VC, for example, they provide critical services that contribute to successful commercialization. The law literature has extensively studied Silicon Valley attorneys, but without an empirical lens. Other service providers are mentioned in studies, but often fail to receive due attention. The innovation literature has studied PSFs in more depth than management, but this trend is improving. Additional research is needed to understand the networking function of institutional intermediaries. Quasi-public programs are well positioned here, often connecting firms to a broader range of private and public stakeholders compared to their counterparts in academia or corporate settings. Entrepreneurial finance has received the most attention, with decades of research. Yet there is continuous innovation, including emergent funding models such as crowdfunding, as well as the evolution of earlier finance sources making the area ripe for continued inquiry. While the VC literature is extensive, literature investigating the relationship between VC and other funding sources is less developed. The impact of crowdfunders and angels on innovation is still unclear. Though at first glance crowdfunding may appear to have less value-added services than angels and VC, recent studies illuminate a number of features, like idea sharing and consumer feedback, which angels and VC may not provide. 36 Page 37 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives In many ways, the journey from research funding to technology commercialization via an entrepreneurial firm conjures up the image of an old suitcase or steamer truck papered with all the tags from the destinations on its journey. Every single intermediary or support organization that has contact with a firm leaves a fading, yet indelible mark. Studying each institutional category in detail allows researchers to not only identify important sources of divergence, but also begin to explore the interdependencies and intersections of different programs. As we note, university TTOs have long been known to partner with incubators and support organizations within their region. Reinforcing this, Fini et al. (2011) recognize that university supports for academic spin-offs can act to reinforce the contribution of other local support mechanisms. In our own research, we introduce the concept of entrepreneurial pathways in order to capture the different combinations and sequences of institutional supports that firms engaged with over time to grow their business and support innovation (Lowe & Feldman, 2017). More than a static inventory, the pathway concept places the firm within a well mapped institutional surrounding. It allows us to study the exact navigational routes that firms use to traverse that regional institutional landscape, and thus offers a unique vantage point for exploring the contribution of multiple institutions in advancing science, innovation, and sustained entrepreneurial growth. As we begin to recognize this fuller institutional picture of a region, it also creates an opportunity to propose an alternative policy narrative—one less focused on evaluating and identifying the best institutional fix and fit, and channeling all resources there—to one that instead considers the longer term entrepreneurial value of having institutional diversity, even redundancy, within a regional ecosystem. 37 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 38 of 60 REFERENCES Aernoudt, R. (2004). Incubators: Tool for entrepreneurship? Small Business Economics, 23, 127-135. Aernoudt, R. (2005). Executive forum: Seven ways to stimulate business angels’ investments. Venture Capital, 7, 4, 359-371. Agrawal, A. K., Catalini, C., & Goldfarb, A. (2011). The geography of crowdfunding. NBER Working Paper #16820. Agrawal, A., Catalini, C., & Goldfarb, A. (2014). Some Simple Economics of Crowdfunding. Innovation Policy and the Economy, 14, 1, 63-97. Arora, A., Fosfuri, A., & Gambardella, A. (2001). Markets for Technology and implications for corporate strategy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10, 2, 419-451. Auerswald, P. E. (2015). Enabling entrepreneurial ecosystems: Insights from ecology to inform effective entrepreneurship policy. Kauffman Foundation Research Series on City, Metro, and Regional Entrepreneurship, October 2015. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2673843 Autio, E., & Thomas, L. D. W. (2014). Innovation ecosystems: Implications for innovation management. In Dodgson, M., Philips, N., & Gann, D. M. (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management, Oxford University Press. Becker, B., & Gassmann, O. (2006). Corporate incubators: industrial R&D and what universities can learn from them. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(4), 469483. 38 Page 39 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Bell-Masterson, J., & Stangler, D. (2015). Measuring an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Arlington, Virginia: Kauffman Foundation. Bercovitz, J., Feldman, M., Feller, I., & Burton, R. (2001). Organizational structure as a determinant of academic patent and licensing behavior: An exploratory study of Duke, Johns Hopkins, and Pennsylvania State Universities. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 26(1), 21-35. Bergek, A., & Norman, C. (2008). Incubator best practice: A framework. Technovation, 28, 20-28. Berger, S. (2013). Making in America. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (1998). The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking & Finance, 22, 613-673 Bernstein, S., Korteweg, A., & Laws, K. (2015). Attracting early stage investors: Evidence from a randomized field experiment. Journal of Finance, forthcoming. Bernstein, S., Giroud, X., & Townsend, R. R. (2016). The Impact of Venture Capital Monitoring. The Journal of Finance, 71, 4, 1591-1622. Bonvillian, W. (2013). Advanced manufacturing policies and paradigms for innovation. Science, 342 (Dec. 6) 1173- 1175. Bottazzi, L., Da Rin, M., & Hellmann, T. F. (2016). The importance of trust for investment: Evidence from venture capital. NBER Working Paper #16923. Branscomb, L. and P. Auerswald (2002). Between invention and innovation, an analysis of funding for early-state technology development. NIST GCR 02-841. Washington, DC: NIST. http://www.atp.nist.gov/eao/gcr02-841/contents.htm. 39 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 40 of 60 Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, Published online May 2, 2017. Bruneel, J., Ratinho, T., Clarysse, B., & Groen, A. (2012). The evolution of business incubators: Comparing demand and supply of business incubation services across different incubator generations. Technovation, 32, 2, 110–21. Bruton, G., Khaul, S., Siegel, D., & Wright, M. (2015). New financial alternatives in seeding entrepreneurship: Microfinance, crowdfunding, and peer-to-peer innovations. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 39(1), 9-26. Bush, V. (1945). Science: The endless frontier. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. http://www.nsf.gov/od/lpa/nsf50/vbush1945.htm. Cable, A. J. B. (2014). Startup lawyers at the outskirts. Willamette Law Review, 50, 163193. Cable, D. M., & Shane, S. (1997). A prisoner's dilemma approach to entrepreneur-venture capitalist relationships. Academy of Management Review, 22, 1, 142-176. Chrisman, J. J., McMullan, E., & Hall, J. (2005). The Influence of Guided Preparation on the Long-Term Performance of New Ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 769– 791. Cohen, S. (2013). What do accelerators do? Insights from incubators and angels. Innovations, 8, 3/4, 19-25. Cohen, W. M. & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 128-152. 40 Page 41 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Colombo, M. G., & Delmastro, M. (2002). How effective are technology incubators? Evidence from Italy. Research Policy, 31(7), 1103-1122. Cooke, P., Urange, M. G., & Extebarria, E. (1997). Regional innovation systems: institutional and organizational dimensions. Research Policy, 26(4-5), 475–493. Corredoira, R. A. & McDermott, G. A. (2014). Adaptation, bridging and firm upgrading: How non-market institutions and MNCs facilitate knowledge recombination in emerging markets. Journal of International Business Studies, 45, 699–722. Cumming, D., & Dai, N. (2010). Local bias in venture capital investments. Journal of Empirical Finance, 17, 362-380. Cumming, D., & Dai, N. (2011). Fund size, limited attention and valuation of venture capital backed firms. Journal of Empirical Finance, 18, 2-15. Cumming, D. J. & Fischer, E. (2012). Publicly funded business advisory services and entrepreneurial outcomes. Research Policy, 41, 467-481. Cunningham, J. A., & Link, A. N. (2016). Exploring the effectiveness of research and innovation policies among European Union countries. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 415-425. Da Rin, M., Hellmann, T., & Puri, M. (2012). A survey of venture capital research. In G. Constantinides, M. Harris, & R. Stulz (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Finance, Vol. 2, North Holland, Amsterdam. Debackere, K., & Veugelers, R. (2005). The role of academic technology transfer organizations in improving industry science links. Research Policy, 34, 321-342. Denis, D. J. (2004). Entrepreneurial finance: An overview of the issues and evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance, 10, 301-326. 41 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 42 of 60 D’Este, P., & Patel, P. (2007). University–industry linkages in the U.K.: What are the factors underlying the variety of interactions with industry? Research Policy, 36, 1295 1313. Di Gregorio, D., & Shane, S. (2003). Why do some universities generate more start-ups than others? Research Policy, 32, 209-27. Dutt, N., Hawn, O., Vidal, E., Chatterji, A., McGahan, A., & Mitchell, W. (2016). How open system intermediaries fill voids in market-based institutions: The case of business incubators in emerging markets. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 3, 818-840. Edquist, C. (1997). Systems of innovation: technologies, institutions, and organizations. New York, NY: Psychology Press Empson, L., Muzio, D., Broschak, J. P., & Hinings, B. (Eds). (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Professional Service Firms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Etzkowitz, H., Webster, A., Gebhardt, C., & Terra, B. R. C. (2000). The future of the university and the university of the future: Evolution of ivory tower to entrepreneurial paradigm. Research Policy, 29, 313-330. Fehder, D. C., & Hochberg, Y. V. (2014). Accelerators and the regional supply of venture capital investment (Social Science Research Network). Feldman, M., Feller, I., Bercovitz, J. & Burton, R. (2002). Equity and the technology transfer strategies of American research universities. Management Science, 48, 1, 105-121. Feldman, M. P., & Kelley, M. R. (2002). How states augment the capabilities of technologypioneering firms. Growth and Change, 33, 173–195. 42 Page 43 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Feldman, M. P. & Kogler, D. F. (2010), “Stylized facts in the geography of innovation.” In B.H. Hall, & N. Rosenberg, (Eds.) Handbook of the Economics of Innovation. Vol 1, (pp. 381-410). North Holland: Amsterdam. Feldman, M., & Lanahan, L. (2010). Silos of small beer: A case study of the efficacy of federal innovation programs in a key Midwest regional economy. Center for American Progress. Feldman, M., & Lowe, N. (2011). “Restructuring for resilience. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 6, 1, 129-146. Feldman, M., & Lowe, N. (2017). How Do Ideas Get Into the Air? Governance and the Construction of Place-specific Innovative Advantage. In H. Bathelt, P. Cohendet, S. Henn & L. Simon (Eds). The Elgar Companion to Innovation and Knowledge Creation, Edward Elgar: Northampton (MA). Feller, I. and M. P. Feldman. (2010). “The commercialization of academic patents: black boxes, pipelines, and Rubik's cubes.” The Journal of Technology Transfer. 35(6): 597-616. Fernández-Esquinas, M., Merchán-Hernández, C., & Valmaseda-Andía, O. (2016). How effective are interface organizations in the promotion of university-industry links? Evidence from a regional innovation system. European Journal of Innovation Management, 19, 3, 424-442. Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Santoni, S., & Sobrero, M. (2011). Complements or Substitutes? The Role of Universities and Local Context in Supporting the Creation of Academic SpinOffs. Research Policy, Special Issue: 30 Years After Bayh-Dole: Reassessing Academic Entrepreneurship, 40, 8, 1113–1127. 43 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 44 of 60 Foertsch, C. (2011, January 13). Deskmag 1st Global Coworking Survey. Obtained from http://www.deskmag.com/en/the-coworkers-global-coworking-survey-168 [Accessed September 23, 2016]. Fraser, S., Kumar Bhaumik, S., & Wright, M. (2015). What do we know about entrepreneurial finance and its relationship with growth? International Small Business Journal, 33, 1, 70-88. Friedman, L. M., Gordon, R. W., Pirie, S., & Whatley, E. (1989). Law, lawyers, and legal practice in Silicon Valley: A preliminary report. Indiana Law Journal, 64, 3, 555-567. Frydrych, D., Bock, A. J., Kinder, T., & Koeck, B. (2014). Exploring entrepreneurial legitimacy in reward-based crowdfunding. Venture Capital, 16, 3, 247-269. Fuzi, A., Clifton, N., & Loudon, G. (2015). New spaces for supporting entrepreneurship? Coworking spaces in the Welsh entrepreneurial landscape. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of entrepreneurship, innovation and regional development, Sheffield, U.K., June 18-19, 309-318. Gilson, R. (1984). Value Creation by Business Lawyers: Legal Skills and Asset Pricing. Yale Law Journal, 94, 239-243. Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2010). Equity financing. In Z.J. Acs, & D.B. Audretsch (Eds.) Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research, International Handbook Series on Entrepreneurship, Vol. 5, (pp. 183-214). Springer: New York. Hackett, S. M., & Dilts, D. M (2004). A Systematic Review of Business Incubation Research. Journal of Technology Transfer, 29, 55–82. Hackett, S. M., & Dilts, D. M (2008). Inside the black box of business incubation: Study B – 44 Page 45 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives scale assessment, model refinement, and incubation outcomes. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 33, 5, 439-471. Hallen, B., Bingham, C., & Cohen, S. (2014). Do Accelerators Accelerate? Working paper. Harrison, R. (2013). Editorial: Crowdfunding and the revitalisation of the early stage risk capital market: Catalyst or chimera? Venture Capital, 15, 4, 283–287. Hart, D. (1998). Forged Consensus: Science, Technology, and Economic Policy in the United States, 1921-1953. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Hayter, C. S. (2016). Constraining entrepreneurial development: A knowledge-based view of social networks among academic entrepreneurs. Research Policy, 45, 475-490. Howells, J. (2006). Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Research Policy, 35, 715–728. Hsu, D. H. (2004). What do entrepreneurs pay for venture capital affiliation? The Journal of Finance, 59, 4, 1805-1844. Hsu, D. H. (2006). Venture capitalists and cooperative startup commercialization strategy. Management Science, 52, 2, 204-219. Huyghe, A., Knockaert, M., Piva, E., & Wright, M. (2016). Are researchers deliberately bypassing the technology transfer office? An analysis of TTO awareness. Small Business Economics, 47, 589-607. Ibrahim, D., (2008). The (not so) puzzling behavior of angel investors. Vanderbilt Law Review, 61, 1405–1452. Isenberg, D. (2011). The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economic policy: principles for cultivating entrepreneurship, Babson Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Project, Babson College, Babson Park: MA 45 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 46 of 60 Kay, L., Youtie, J., & Shapira, P. (2013). Signs of things to come? What patent submissions by small and medium-sized enterprises say about corporate strategies in emerging technologies. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 85, 17-25. Kenney, M., Han, K., & Tanaka, S. (2002). Scattering Geese: The Venture Capital Industries of East Asia: A Report to the World Bank. In UCAIS Berkeley Roundtable on the International Economy. University of California Berkeley: Berkeley. Kenney, M., & Patton, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial geographies: Support networks in three high-technology industries. Economic Geography, 81, 2, 201-228. Kerr, W. R., & Nanda, R. (2015). Financing innovation. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 7, 445-462. Kerr, W. R., Nanda, R., & Rhodes-Kropf, M. (2014). Entrepreneurship as Experimentation. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28, 3, 25-48. Kim, S. & Jeong, M. (2014). Discovering the genesis and role of an intermediate organization in an industrial cluster: focusing on CONNECT of San Diego. International Review of Public Administration, 19, 2, 143-149. Kim, J., & Wagman, L. (2014). Portfolio size and information disclosure: An analysis of startup accelerators. Journal of Corporate Finance, 29, 520-534. Kline, D. (2003) Sharing the corporate crown jewels. MIT Sloan Management Review, 44, 89–93. Kohler, T. (2016). Corporate accelerators: Building bridges between corporations and startups. Business Horizons, 59, 347-357. Kortum, S., & Lerner, J. (2000). Assessing the contribution of venture capital to innovation. The Rand Journal of Economics, 31, 674-692. 46 Page 47 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Lanahan, L. (2016). Multilevel public funding for small business innovation: a review of US state SBIR match programs. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41, 220-249. Lanahan, L., & Feldman, M. P. (2015). Multilevel innovation policy mix: A closer look at state policies that augment the federal SBIR program. Research Policy, 44, 13871402. Lanahan, L., & Feldman, M. P. (2017). Approximating exogenous variation in R&D: Evidence from the Kentucky and North Carolina SBIR State Match Programs. Review of Economics and Statistics. Advanced online publication. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00681. Lee, S., Park, G., Yoon, B. & Park, J. (2010). Open innovation in SMEs—An intermediated network model. Research Policy, 39, 290–300. Lehner, O. M., Grabmann, E., & Ennsgraber, C. (2015). Entrepreneurial implications of crowdfunding as alternative funding source for innovations. Venture Capital, 17, 12, 171-189. Lerner, J. (1999). The government as venture capitalist: The long-run impact of the SBIR program. The Journal of Business, 72, 3, 285-318. Lerner, J. (2002). When bureaucrats meet entrepreneurs: The design of effective 'public venture capital' programmes. The Economic Journal, 112, F73-F84. Lerner, J. (2009). The Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed—and What to Do About It. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Lewis, D. A., Harper-Anderson, E., & Molnar, L. A. (2011). Incubating Success: Incubation Best Practices that Lead to Successful New Ventures. Institute for Research on Labor Employment, and the Economy. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. 47 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 48 of 60 Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2010). Government as entrepreneur: Evaluating the commercialization success of SBIR projects. Research Policy, 39, 589-601. Lowe, N. & Feldman, M. (2015). Breaking the Waves: Innovating at the Intersections of Local Economic Development Planning. American Association of Geographers, Conference paper. Chicago, Illinois. Lowe, N., & Feldman, M. (2017). Institutional Life Within an Entrepreneurial Region. Geography Compass, 11(3). Mack, E., & Mayer, H. (2015). The evolutionary dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Urban Studies, 53, 10, 2118-2133. Maine, E. (2008). Radical innovation through internal corporate venturing: Degussa’s commercialization of nanomaterials. R&D Management, 38, 4, 359-371. Markman, G. D., Phan, P. H., Balkin, D. B., & Gianiodis, P. T. (2005). Entrepreneurship and university based technology transfer. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 241–264. Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. Background paper for workshop organized by the OECD LEED Programme and the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs on Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship, 7th November 2013. McEvily, B. & Zaheer, A. (1999). Bridging ties: a source of firm heterogeneity in competitive capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 12, 1133–1156. Mian, S. A. (1996). Assessing value-added contributions of university technology business incubators to tenant firms. Research Policy, 25, 325-335. Mian, S. A. (1997). Assessing and Managing the University Technology Business Incubator: An Integrative Framework. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 4, 251–285. 48 Page 49 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Mian, S., Lamine, W., & Fayolle, A. (2016). Technology Business Incubation: An overview of the state of knowledge. Technovation, 50-51, 1-12. Mollick, E. (2014). The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 29, 1-16. Moriset, B. (2014). Building new places of the creative economy. The rise of coworking spaces. Proceedings of the 2nd Geography of Innovation, International Conference, Utrecht University, Utrecht (The Netherlands). Mowery, D. C., Nelson, R. R., Sampat, B. N., & Ziedonis, A. A. (2004). Ivory Tower and Industrial Innovation: University-Industry Technology Transfer Before and After the Bayh-Dole Act in the United States. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Nanda, R., & Rhodes-Kropf, M. (2013). Investment cycles and startup innovation. Journal of Financial Economics, 110, 403-418. Nelson, R. R. and N. Rosenberg. (1993). "Technical innovation and national systems," in National innovation systems: a comparative analysis, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993. O’Shea, R. P., Allen, T .J., Chevalier, A., & Roche, F. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation, technology transfer and spinoff performance of U.S. universities. Research Policy, 34, 994-1009. Owen-Smith, J., & Powell, W. (2006). Accounting for emergence and novelty in Boston and Bay Area biotechnology. In P. Braunerhjelm & M. P. Feldman (Eds.), Cluster Genesis: Technology-Based Industrial Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pahnke, E. C., McDonald, R., Wang, D., & Hallen, B. (2015). Exposed: Venture capital, 49 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 50 of 60 competitor ties, and entrepreneurial innovation. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 5, 1334-1360. Parrino, L. (2015). Coworking: assessing the role of proximity in knowledge exchange. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 13, 261-271. Patton, D., & Kenney, M. (2005). The spatial configuration of the entrepreneurial support network for the semiconductor industry. R&D Management, 35, 1, 1-16. Pauwels, C., Clarysse, B., Wright, M., & van Hove, J. (2015). Understanding a new generation incubation model: The accelerator. Technovation, 50-51, 13-24. Pergelova, A., & Angulo-Ruiz, F. (2015). The impact of government financial support on the performance of new firms: the role of competitive advantage as an intermediate outcome. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26, 9-10, 663-705. Phan, P. H., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2005). Science parks and incubators: observations, synthesis and future research. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(2), 165-182. Pierrakis, Y., & Saridakis, G. (2017). Do publicly backed venture capital investments promote innovation? Differences between privately and publicly backed funds in the U.K. venture capital market. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 7, 55-64. Pinch, S., & Sunley, P. (2009). Understanding the role of venture capitalists in knowledge dissemination in high-technology agglomerations: A case study of the University of Southampton spin-off cluster. Venture Capital, 11, 4, 311-333. Powell, W. W. (1990). Neither market nor hierarchy: Network forms of organization. In. Staw, B. M., Cummings, L. L. (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, 12. pp. 295–336 Qian, H., & Haynes, K. E. (2014). Beyond innovation: Small Business Innovation 50 Page 51 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Research program as entrepreneurship policy. Journal of Technology Transfer, 39, 524-543. Rector, A. M., & Thursby, M. C. (2016). Licensing Inventions from Entrepreneurial Universities: The Context of Bayh–Dole. In (Eds.) Thursby, M.C., Technological Innovation: Generating Economic Results. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 361-413 Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 2), S71-S102. Rothaermel, F. T., Agung, S. D., & Jiang, L. (2007). University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Industrial & Corporate Change, 16, 4, 691-791. Samila, S., & Sorenson, O. (2010). Venture capital as a catalyst to commercialization. Research Policy, 39, 1348-1360. Schrank, A., & Whitford, J. (2009). Industrial policy in the United States: A Neo-Polanyian interpretation. Politics & Society, 37, 4, 521-553. Schwartz, M. (2013). A control group study of incubators’ impact to promote firm survival. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38, 3, 302–31. Schwartz, M., & Hornych, C. (2010). Cooperation patterns of incubator firms and the impact of incubator specialization: Empirical evidence from Germany. Technovation, 30, 485-495. Shane, S. (2001). Technological Opportunities and New Firm Creation. Management Science, 47, 2, 205-220. 51 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 52 of 60 Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D., & Link, A. (2003). Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the relative productivity of university technology transfer offices: An exploratory study. Research Policy, 32, 27-48. Siegel, D. S., Waldman, D. A., Atwater, L. E., & Link, A. N. (2004). Toward a model of the effective transfer of scientific knowledge from academicians to practitioners: Qualitative evidence from the commercialization of university technologies. Journal of Engineering and Management, 21, 115-142. Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2015a). University Technology Transfer Offices, Licensing, and Start-ups. In. Link, A.N., Siegel, D.S., & Wright, M. (Eds.) The Chicago Handbook of University Technology Transfer and Academic Entrepreneurship, Chicago Scholarship Online. Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2015b). Academic Entrepreneurship: Time for a Rethink? British Journal of Management, 26, 582-595. Smith, S. W., & Hannigan, T. J. (2015). Swinging for the fences: How do top accelerators impact the trajectories of new ventures. DRUID15, Rome. Retrieved from: http://druid8. sit. aau. dk/druid/acc_papers/5ntuo6s1r5dvrpf032x24x5on5lq. pdf. Sohl, J. E. (1999). The early-stage equity market in the USA. Venture Capital, 1, 2, 101-120. Spigel, B. (2015). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: A Sympathetic Critique. European Planning Studies, 23, 9, 1759–1769. Stanko, M. A., & Henard, D. H. (2016). How crowdfunding influences innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 57, 3, 15-17. 52 Page 53 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Stokes, D. (1997). Pasteur’s quadrant, basic science and technological innovation. Brookings Institute Press: Washington, DC. Suchman, M. C. (2000). Dealmakers and counselors: law firms as intermediaries in the development of Silicon Valley. In M. Kenney (Ed.). Understanding Silicon Valley: The Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region (pp. 71–97). Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA. Suchman, M. C., & Cahill, M. L. (1996). The hired gun as facilitator: Lawyers and the suppression of business disputes in Silicon Valley. Law & Social Inquiry, 21, 3, 679712. Suvinen, N., Konttinen, J., & Nieminen, M. (2010). How necessary are intermediary organizations in the commercialization of research? European Planning Studies, 18, 9, 1365-1389. Theodorakopoulos, N., Kakabadse, N. K., & McGowan, C. (2014). What matters in business incubation? A literature review and a suggestion for situated theorising. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21, 4, 602-622. Thursby, J. G., & Kemp, S. (2002). Growth and productive efficiency of university intellectual property licensing. Research Policy, 31, 1, 109–124. Thursby, J. G., & Thursby, M. C. (2002). Who is selling the ivory tower? Sources of growth in university licensing. Management Science, 48, 1, 90-104. Todeva, E. (2013). Governance of innovation and intermediation in Triple Helix interactions. Industry & Higher Education, 27, 4, 263-278. Vanacker, T., Collewaert, V., & Paeleman, I. (2013). The relationship between slack 53 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 54 of 60 resources and the performance of entrepreneurial firms: The role of venture capital and angel investor. Journal of Management Studies, 50, 6, 1070-1096. Von Nordenflycht, A. (2010). What is a professional service firm? Toward a theory and taxonomy of knowledge-intensive firms. Academy of Management Review, 35, 1, 155–174. Walcott, S. M. (2002). Analyzing an innovative environment: San Diego as a bioscience beachhead. Economic Development Quarterly, 16, 2, 99–114. Waters-Lynch, J., Potts, J., Butcher, T., Dodson, J., & Hurley, J. (2016). Coworking: A transdisciplinary overview. Working Paper. Wessner, C. W. (2002). Entrepreneurial finance and the New Economy. Venture Capital, 4, 4, 349-355. Wright, M., Lockett, A., Clarysse, B., & Binks, M. (2006). University spin-out companies and venture capital. Research Policy, 35, 481-501. Wright, M., Clarysse, B., Lockett, A., & Knockaert, M. (2008). Mid-range universities’ linkages with industry: Knowledge types and the role of intermediaries. Research Policy, 37, 1205-1223. Yusuf, J. (2010). Meeting entrepreneurs’ support needs: are assistance programs effective? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 17, 2, 294-307. Zahra, S. A. & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27, 185–203. Zhang, Y., & Li, H. (2010). Innovation search of new ventures in a technology cluster: The role of ties with service intermediaries. Strategic Management Journal, 31, 1, 88109. 54 Page 55 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives Paige Clayton (clayton3@live.unc.edu) is a doctoral student in the Department of Public Policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she received the 2014 Nancy W. Stegman Fellowship in Public Policy. Her research focuses on the areas of innovation, entrepreneurship, economic development, and science and technology policy. Maryann Feldman (maryann.feldman@unc.edu) is the Heninger Distinguished Professor in the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Public Policy Department, and a Research Director at UNC Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise. Feldman’s research focuses on the areas of innovation, commercialization of academic research, and factors that promote technological change and economic growth. Nichola Lowe (nlowe@email.unc.edu) is an Associate Professor in City and Regional Planning at UNC-Chapel Hill. Lowe’s work focuses on the institutional arrangements that lead to more inclusive forms of economic development and specifically, the role that practitioners can play in aligning growth and equity goals. 55 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Page 56 of 60 APPENDIX A Literature search keyword combinations: (1) intermedia* AND (technology commercialization OR academic entrepreneurship) AND spin-off AND (local OR region) (a) intermedia* AND spin-off AND (technology commercialization OR academic entrepreneurship) (2) ((intermedia* AND spin-off) OR (commercial* OR tech* transfer OR entrepreneur*)) AND university technology transfer/licensing office AND (local OR region) (a) intermedia* AND spin-off AND university technology transfer/licensing office (3) ((intermedia* AND spin-off) OR (commercial* OR tech* transfer OR entrepreneur*)) AND (KIBS OR professional service firm) AND (local OR region) (a) intermedia* AND (entrepreneur* OR spin-off) AND (KIBS OR professional service firm) 56 Page 57 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Academy of Management Perspectives (4) ((intermedia* AND spin-off) OR (commercial* OR tech* transfer OR entrepreneur*)) AND (government support program OR nonprofit support program) AND (local OR region) (a) intermedia* AND (entrepreneur* OR spin-off) AND (government support program OR nonprofit support program) (5) ((intermedia* AND spin-off) OR (commercial* OR tech* transfer OR entrepreneur*)) AND (incubator OR accelerator OR coworking space) AND (local OR region) (a) intermedia* AND spin-off AND (incubator OR accelerator OR coworking space) (6) ((intermedia* AND spin-off) OR (commercial* OR tech* transfer OR entrepreneur*)) AND (venture capital OR angel OR crowdfunding OR public funding OR government funding) AND (local OR region) (a) intermedia* AND spin-off AND (venture capital OR angel OR crowdfunding OR public funding OR government funding) 57 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 Page 58 of 60 Table 1. Intermediary Definitions and Roles in Scientific Entrepreneurship Intermediary Type Definition Primary Roles in Scientific Entrepreneurship Service Intermediaries Provide incentives for invention disclosure University Technology University offices that manages intellectual property of Transfer/ Licensing Offices university-created technologies. Engage faculty in development process Work with businesses to license technology Reduce transaction costs Third-party firms—including law, accounting and real Professional Service Firms Advise IP and business formation strategy estate firms—that provide resources and connections. Act as dealmakers Other Assisting Public, quasi-public and nonprofits that provide Facilitate networking and mentoring Organizations networking, specialized services and programs. Influence policy through agenda setting Physical Space Intermediaries Offer affordable space A physical space for early stage firm formation and idea Incubators Provide support services development. Generate revenue for incumbent firms 59 Page 59 of 60 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 Accelerators Academy of Management Perspectives A physical space, complemented with provision of Offer intensive programming resources and financial investment. Accelerate milestones Invest in exchange for equity Provide flexible, less structured programming A physical space that promotes proximity and Coworking Spaces Offer space for social interaction interaction. Facilitate networking and peer mentoring Financial Intermediaries Investment firms that raise funds from individuals and Provide multistage, benchmarked financing Venture Capital Firms institutions to support new ventures with high growth Motivated to increase firm performance potential. Provide early stage funding Individual investors or investment clubs that provide Angel Investors Source of patient capital early-stage financing in support of new ventures. Offer business advice and mentoring Long term source of support Public and quasi-public programs that provide financial Public Funding Programs Non-dilutive source of funding assistance in the form of grants or loans to new ventures. Signal quality for private financing mechanisms 60 Academy of Management Perspectives 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 Page 60 of 60 Recession proof Funding platform to secure large numbers of small Crowdfunding Platforms Enable inventors to gain immediate product feedback investments. Support idea sharing 61