Types of Assets: Classification, Properties, and Net Identifiable Assets

advertisement

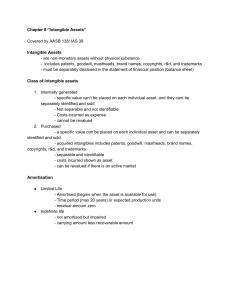

What Are the Main Types of Assets? An asset is a resource owned or controlled by an individual, corporation, or government with the expectation that it will generate future cash flows. Common types of assets include: current, noncurrent, physical, intangible, operating, and non-operating. Correctly identifying and classifying the types of assets is critical to the survival of a company, specifically its solvency and associated risks. The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) framework defines an asset as follows: “An asset is a resource controlled by the enterprise as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise.” Examples of assets include: Cash and cash equivalents Inventory Investments PPE (Property, Plant, and Equipment) Vehicles Furniture Patents (intangible asset) Stock Properties of an Asset There are three key properties of an asset: Ownership: Assets represent ownership that can be eventually turned into cash and cash equivalents Economic Value: Assets have economic value and can be exchanged or sold Resource: Assets are resources that can be used to generate future economic benefits Classification of Assets Assets are generally classified in three ways: 1. Convertibility: Classifying assets based on how easy it is to convert them into cash. 2. Physical Existence: Classifying assets based on their physical existence (in other words, tangible vs. intangible assets). 3. Usage: Classifying assets based on their business operation usage/purpose. Classification of Assets: Convertibility If assets are classified based on their convertibility into cash, assets are classified as either current assets or fixed assets. An alternative expression of this concept is short-term vs. long-term assets. 1. Current Assets Current assets are assets that can be easily converted into cash and cash equivalents (typically within a year). Current assets are also termed liquid assets and examples of such are: Cash Cash equivalents Short-term deposits Stock Marketable securities Office supplies 2. Fixed or Non-Current Assets Non-current assets are assets that cannot be easily and readily converted into cash and cash equivalents. Non-current assets are also termed fixed assets, long-term assets, or hard assets. Examples of non-current or fixed assets include: Land Building Machinery Equipment Patents Trademarks Classification of Assets: Physical Existence If assets are classified based on their physical existence, assets are classified as either tangible assets or intangible assets. 1. Tangible Assets Tangible assets are assets that have a physical existence (we can touch, feel, and see them). Examples of tangible assets include: Land Building Machinery Equipment Cash Office supplies Stock Marketable securities 2. Intangible Assets Intangible assets are assets that do not have a physical existence. Examples of intangible assets include: Goodwill Patents Brand Copyrights Trademarks Trade secrets Permits Corporate intellectual property Classification of Assets: Usage If assets are classified based on their usage or purpose, assets are classified as either operating assets or non-operating assets. 1. Operating Assets Operating assets are assets that are required in the daily operation of a business. In other words, operating assets are used to generate revenue from a company’s core business activities. Examples of operating assets include: Cash Stock Building Machinery Equipment Patents Copyrights Goodwill 2. Non-Operating Assets: Non-operating assets are assets that are not required for daily business operations but can still generate revenue. Examples of non-operating assets include: Short-term investments Marketable securities Vacant land Interest income from a fixed deposit Importance of Asset Classification Classifying assets is important to a business. For example, understanding which assets are current assets and which are fixed assets is important in understanding the net working capital of a company. In the scenario of a company in a high-risk industry, understanding which assets are tangible and intangible helps to assess its solvency and risk. Determining which assets are operating assets and which assets are non-operating assets is important to understanding the contribution of revenue from each asset, as well as in determining what percentage of a company’s revenues comes from its core business activities. What is Net Identifiable Asset? Net Identifiable Assets (NIA) consists of the assets acquired from a company whose value can be measured at a given point of time and its future benefit to the company is recognizable. NIA is used for Purchase Price Allocation (PPA) and the calculation of Goodwill in Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A). The prefix “Net” here means after deducting the liabilities that also come along with the acquisition. Components of Net Identifiable Assets Identifiable assets are assets that the acquired company includes in the list of balance sheet items. The asset amount that is not on the balance sheet is to be put under “Goodwill.” The amount of the goodwill is relative to the amount that an acquiring company paid and is essentially based on the perception and assumptions of the acquiring company. This is the reason that Goodwill is not considered a part of Net Identifiable Assets. Example – Calculation of Net Identifiable Assets and Goodwill Let us see the concept of Net Identifiable Assets and Goodwill through an example: An acquirer has paid $20,000 to purchase another company. The assets that are posted on the acquired company are all identifiable assets. The amount paid over and above the value of Net Identifiable assets, i.e. the value of total assets less total liabilities, is the amount of Goodwill. Goodwill is not included on the acquired company’s balance sheet because it is not an “Identifiable Asset” and is only reported on the balance sheet when acquired. The value of Goodwill is not empirically verifiable and thus remains an unidentifiable asset even after acquisition. Its value is incidental to the amount the acquirer pays during the acquisition, which might differ from case to case. Identifiable intangible assets and goodwill As per the CON5 asset recognition criteria, an asset is recognized if it meets the definition of an asset, has a relevant attribute measurable with sufficient reliability, and the information about it is representationally faithful, verifiable, neutral (i.e., it is reliable), and capable of making a difference in user decisions (i.e., it is relevant). For intangible assets to be separately identified from goodwill, the abovementioned criterion along with the ones below must be fulfilled: 1. Legal (or Contractual) – Control over the future economic benefits of the asset results from contractual or other legal rights (regardless of whether those rights are transferable or separable from other rights and obligations); or 2. Separability – The asset is capable of being separated or divided and sold, transferred, licensed, rented, or exchanged (regardless of whether there is an intent to do so or whether a market currently exists for that asset), or, if it cannot be individually sold, etc., it is capable of being sold, transferred, licensed, rented or exchanged along with a related contract, asset, or liability. All intangible assets acquired from other enterprises or individuals, whether singly, in groups, or as part of a business combination, are recognized initially and are measured based on their respective fair values. Under the provisions of ASC 350, however, a serious effort must be directed to identifying the various intangibles acquired. Valuation Techniques Learn the most important valuation techniques in CFI’s Business Valuation course! Step by step instruction on how the professionals on Wall Street value a company. Real estate business intelligence: it’s never been easier to get the insight you need It’s no secret that real estate companies have tended to lag behind those in other sectors in terms of the adoption of new technologies. Yet, one area in which we’re seeing a rapid uptake is in business intelligence and data analysis solutions. It shouldn’t really be a surprise; businesses are collecting more data than ever before and, with a range of increasingly powerful tools available, it’s never been easier to get the valuable insight you need to drive your business forward. Enhanced native analytics In your day-to-day role, you will already use a variety of software solutions from email platforms to property management systems and each of these will have their own reporting features and functionality. All encompassing decision making potential There is a general acceptance that a team is much more effective when it’s pulling in the same direction. Although getting everyone in a global business on the same page is easier said than done, there has been a firm move away from silo culture and it is easier than ever to access important datasets from other departments. More importantly, powerful tools now exist that can help you pull all that data together and turn it into something incredibly valuable for your entire organisation. If you run a retail business, you can now see what stock you have on the shelf in real time, add third party datasets to build up a picture of trends and opportunities, project store P&L and even analyze, forecast and simulate the effect of promotions on sales and margins. As the asset management industry faces tighter margins and an increasingly digital client landscape, effectively leveraging data has become crucial to remaining competitive. While many managers have implemented business intelligence functions to enhance decision-making in the Distribution space, dashboards and reporting which merely identify baseline business activity (e.g., net new flows in a certain region) are insufficient to make data a true competitive advantage. Asset managers must prioritize investment in the technical and organizational infrastructures to promote the predictive capabilities necessary to differentiate themselves and gain market share. A wealth of data is held by organizations in disparate systems such as maintenance management, enterprise resource planning (ERP), process control, process historians, condition monitoring, asset integrity management and a plethora of spreadsheets. Typically these data sets are stored and analyzed independently, however, maintenance and reliability practitioners frequently have to bring data together from multiple sources to support decision making or to identify improvement opportunities. And these processes can often be challenging, inefficient and timeconsuming, with the effectiveness of the outcome influenced by the spreadsheet skills and determination of the individual. The latest generation of business intelligence (BI) tools, often already available and being used within an organization, are an efficient, repeatable way to draw information together and present a more complete and timely picture of asset performance and asset health. Whereas these BI tools can open up endless possibilities for data analysis, data visualization and the calculation of performance metrics that are potentially “interesting”, challenges lie in the inconsistency of data across systems, gaps in data sets, inaccuracies in data and differing thoughts on how to use the data to address organizational imperatives. Using case studies from a variety of gas machinery and industrial applications, this paper explores the challenges and benefits of the BI tools approach to analyzing asset performance and asset management programs. 2. The digital opportunity The digital age, if nothing else, provides us with a dizzying array of big numbers. A few keyword searches and clicks and you can find all kinds of numbers and statistics: Gas turbines generating 500+ gigabytes of data every day, more than 50 billion devices to be connected to the internet of things (IoT), 40,000 exabytes (trillion gigabytes) of stored data by 2020, and new terms invented to cope with the exponential growth – the dinosaur-like Brontobytes tipping the scales at 1027 bytes caught this father’s attention (1) and (2). Financial numbers are no less impressive, according to a recent McKinsey report (3), “the IoT brings with it a total potential economic impact of up to $11.1 trillion by 2025”. Most relevantly for us, the resources sector is likely to be affected significantly, where the economic effect of connected devices and analytics may reach $1T. Critically, the report also paints a picture of winners and losers; the winners being those companies who find ways to extract insights and value from their IoT data, and the stragglers who risk losing out to competitors. So what are the leading companies doing and what is on their minds? The Accenture 2017 Digital Refinery Survey (4) confirms that the current focus is clearly on cost reduction, and while “new digital technologies are not currently the top investment priority”, digital spend will increase in coming years to support this. Of that digital spend, analytics has been identified as having the greatest potential impact on operational performance. 3. Analytics, big data and business intelligence So while analytics is nothing new (UPS started an analytics group in 1954!), what has changed is the volume and variety of data that can now potentially be analyzed. “Big data” essentially describes a new opportunity provided by the structured rows and columns stored in today’s data warehouses, databases and spreadsheets, and the unstructured video, sound and images being captured by new technologies (drones, thermal cameras, etc.) and stored in new “data lakes”.