Industrial Companies Evaluation Criteria in New Product Development Gates- JPIM 2003 (2)

advertisement

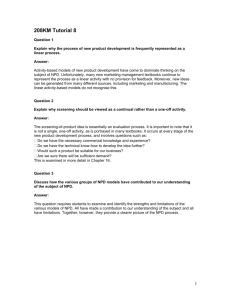

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 r 2003 Product Development & Management Association Industrial Companies’ Evaluation Criteria in New Product Development Gates Susan Hart, Erik Jan Hultink, Nikolaos Tzokas, and Harry R. Commandeur This article presents the results of a study on the evaluation criteria that companies use at several gates in the NPD process. The findings from 166 managers suggest that companies use different criteria at different NPD evaluation gates. While such criteria as technical feasibility, intuition and market potential are stressed in the early-screening gates of the NPD process, a focus on product performance, quality, and staying within the development budget are considered of paramount importance after the product has been developed. During and after commercialization, customer acceptance and satisfaction and unit sales are primary considerations. In addition, based on the performance dimensions developed by Griffin and Page (1993), we derive patterns of use of various evaluative dimensions at the NPD gates. Our results show that while the market acceptance dimension permeates evaluation at all the gates in the NPD process, the financial dimension is especially important during the business analysis gate and after-market launch. The product performance dimension figures strongly in the product and market testing gates. The importance of our additional set of criteria (i.e., product uniqueness, market potential, market chance, technical feasibility, and intuition) decreases as the NPD process unfolds. Overall the above pattern of dimensions’ usage holds true for both countries in which we collected our data, and across firms of different sizes, holding different market share positions, with different NPD drivers, following different innovation strategies, and developing different types of new products. The results also are stable for respondents that differ in terms of expertise and functional background. The results of this study provide useful guidelines for project selection and evaluation purposes and therefore can be helpful for effective investment decisionmaking at gate-meetings and for project portfolio management. We elaborate on these guidelines for product developers and marketers wishing to employ evaluation criteria in their NPD gates, and we discuss directions for further research. Introduction R ecent investigations of new product developments (NPD) have reinforced the concept of a process based on a series of develop- Address correspondence to Susan Hart, Department of Marketing, University of Strathclyde, Stenhouse Building, 173 Cathedral Street, Glasgow G4 0RQ, Scotland, UK. Phone: +44-141-548-4927; E-mail: susan.hart@strath.ac.uk. ment stages interpolated by a series of evaluative stages [9,31,37]. Preceded by the formulation of new product strategy (also coined Protocol [7] and Product Innovation Charter [12]), the development stages include idea generation, concept development, building the business case, product development, market testing, and market launch [7,13]. After each of these stages an evaluation takes place, essentially to determine whether the new product should advance INDUSTRIAL COMPANIES’ EVALUATION CRITERIA IN NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT GATES BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Susan Hart is vice dean of research at Strathclyde Business School. In addition, Professor Hart has worked for a variety of private sector companies, ranging from multinational to small manufacturers in consumer and industrial enterprises. She sits on the executive committee of the Academy of Marketing and recently was elected to the Senate of the Chartered Institute of Marketing. Furthermore she edits the Journal of Marketing Management and is a member of the Journal of Product Innovation Management. She also acts as reviewer for seven other academic journals and is a proposal reviewer for four grant-awarding bodies. Erik Jan Hultink is an Associate Professor of Marketing at the Faculty of Design, Engineering and Production of Delft University of Technology, where he received his PhD. He received his MSc in Economics from the University of Amsterdam. His research interest concentrates on launch strategies and new product development methods and measurement. He has published on these topics in journals such as the International Journal of Research in Marketing, the Journal of Product Innovation Management and the Journal of High Technology Management Research. Nikos Tzokas is Professor of Marketing at the University of East Anglia. He graduated and received an MBA from the Athens University of Economics in Greece. He was awarded a PhD in 1993 from the School of Management at the University of Bath. Formerly at the University of Strathclyde and the University of Stirling, he joined the School of Management in November 2000. His research areas of interest include Relationship Marketing, Customer Relationship Management, New Product Development, and Sales Management. He has published widely on these issues in journals such as The Journal of Selling and Major Account Management, Industrial Marketing Management, International Business Review and the Journal of Product Innovation Management and the Journal of Marketing Management. Harry R. Commandeur holds the Dr. F.J.D. Goldschmeding Chair of Economics for Increasing Returns at Nyenrode University, Breukelen, The Netherlands. He also teaches at the Department of Marketing and Organization, Faculty of Economics, Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands. further or should be terminated. These evaluation stages have been termed gates [7] or convergent points [21]. Such an evaluation requires the collection and consideration of information and the application of criteria against which this information can be assessed. Much research into NPD has dealt with the techniques used for the collection of relevant information [30,31], yet more articles have been published regarding the intricacies of disseminating and using such information [28]. In contrast, the subject of criteria to be used in evaluating the information inputs to NPD is scant, and where it does exist, it tends to be confined to articles dealing with the idea and concept screening gates [8,14]. The criteria act as guideposts against which the performance of the NPD effort can be evaluated and adjustments can be made if necessary [34]. To the J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 23 extent that these criteria are derived from the corporate and new product strategy of the firm and are focused to the specific requirements of each stage of the NPD process, they can help reduce managerial uncertainty and can identify areas where additional attention and resources are needed. Furthermore, they can strengthen the strategic decision-making process of the firm by helping management develop and can deploy the right competencies and resources across the NPD effort. As Hauser and Zettelmeyer [23] maintain, ‘‘Select the right metric for each activity and you can encourage the right decisions and actions by scientists, engineers, and managers’’ (p. 32). That said, key writers observe that the ‘‘go/ kill’’ decision points often are missing from representations and studies of the NPD process [7,34]. Motivated by the important role of criteria throughout the NPD effort, we attempt here to shed additional light on the nature and utilization of these criteria in contemporary industrial firms. The aim of this article is to examine how the use of different criteria varies at different gates of the NPD process. The remainder of this article is divided into four sections. First, we review the NPD literature in order to define our conceptual framework for study and to specify our research questions based on this conceptualization. Second, we describe a survey of the procedures of 166 industrial firms for evaluating new product projects as they evolve from incomplete ideas to nascent products and thus become increasingly resource-hungry [9,30,36]. Then we present results of the study, and last, we discuss their research and managerial implications. Background and Research Questions Despite the changes in the conceptualization of NPD projects that have taken place over the past 25 years, evaluation of the development project as it journeys from intangible idea to actual customer offering remains central [16,27,35]. Indeed, much research demonstrates that a phased review process commonly is used [6,7,17]. Even research disputing the efficacy of the traditional linear, sequential representation of the NPD process tends to recognize the central role of evaluation and the reevaluation of the development project as it progresses [3,20,21]. Common to all phased review representations of the NPD process is the notion that it is made up of development phases 24 J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 (i.e., development stages) and evaluation phases (i.e., corresponding evaluation gates). Evaluation within a gate includes techniques that may be repeated as alternative or refined design concepts of product configurations are developed. Different techniques are used to assess the commercial and technical feasibility of the developing product. The commercial set of techniques includes beta-testing, perceptual mapping, conjoint analysis, Quality Function Deployment (QFD), A-T-R models, break-even analysis, and sensitivity testing. In addition to these commercial evaluation techniques, technical evaluation sets include the assessment of design, production, and functional feasibility and specifications. In short, as well as commercial evaluation and reevaluation, it is of critical importance to evaluate the function, form, and production of the new product project. Each gate is a different combination of technical and commercial evaluation sets. Idea screening is the first of a series of evaluations, beginning when the collection of new product ideas is complete. It is an initial assessment to weed out impractical ideas. This initial evaluation cannot be very sophisticated, as it is concerned with identifying ideas that can be developed into concepts and can be evaluated for their technical feasibility and market potential. As the development project proceeds, the information collected regarding both technical and commercial feasibility becomes more copious, and because it relates less to something vague and abstract and more to something tangible and complete, the information has greater potential for being reliable and valid [7]. Thus, when a project reaches market testing, the information yielded will be more complete and will encompass customer opinions, buying behavior, operation of the product in use, production and delivery, and communication to its target market. Yet despite the recognition that the amount and quality of information increases incrementally through each stage of the NPD process, the criteria used to evaluate the information remain unclear. It has been 15 years since Ronkainen’s [33] observation that ‘‘a major issue that has been overlooked is whether or not the same set of criteria is used at every decision-making point or whether the weights of individual criteria vary from one point to another’’ (pp. 171–72). Apart from this one study, however, there has been little further light shed on this matter. Ronkainen [32] found that in four industrial companies, decision- S. HART ET AL. makers used three sets of criteria for evaluative purposes: product, market, and finance, with the last category being of greatest importance. Further, he found that market criteria were determinants of the go/no-go decision at the concept screening gate and that during the product testing gate, product-related criteria took over as being more important. Finally, he suggested that financial criteria were stressed more in the last two gates of the NPD process, which he defined as scale-up and standardization. Despite the important contribution of these findings to our understanding of how NPD processes are applied within firms, they are limited in some respects. First, the small scale of the study, coupled with its age and restriction to large, American firms, make it unwise to assume general applicability of the findings to NPD evaluation. Second, the conceptualization of the process used, while relevant for the four firms investigated, makes no reference to common frameworks used to depict the work of new product developers, and it is therefore difficult to slot the implications into the mainstream of NPD research and theory. A further knowledge gap regarding evaluation criteria relates to the evaluative dimensions to be used during the evaluation gates. With the exception of those articles dealing with idea and concept screening, or post-launch evaluation, the literature as yet has not made a consistent attempt to provide insights into how the evaluative dimensions are deployed throughout the NPD process [8,18,24]. Below, we argue that criteria related to new product performance measures can become the basis for examining the evaluative dimensions for NPD gates. The measurement of new product performance has been the subject of significant research studies within the past 10 years [18,19,20,24]. Such research has affirmed that there are several dimensions of NPD performance, including technical-, financial-, and market-based performance [18,20]. The findings of these studies can be linked to the criteria used in the monitoring of an NPD project. In other words, if there are different kinds of new product performance outcomes to be achieved, then the use of evaluative criteria related to the performance dimensions would be an appropriate means of steering the NPD process through the go/no-go evaluation gates. More specifically, as new product performance on one dimension may be achieved at the expense of performance on another, it is crucial that the evaluative criteria at the gates mirror those used to INDUSTRIAL COMPANIES’ EVALUATION CRITERIA IN NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT GATES assess the performance of the product once launched. In our research, we sought explicitly to incorporate the dimensions of new product performance detailed in the literature in investigating how NPD projects are evaluated throughout their development. In short, we have synthesized the concepts of evaluative criteria and performance indicators. The work of Hauser [22] and Hauser and Zettelmeyer [23] supports our approach. Using a three-tier metaphor to categorize different types of research, development, and engineering (RD&E) activities (i.e., projects, programs, and explorations) in 10 research-intensive organizations, Hauser and Zettelmeyer [23] found that the appropriateness of different metrics varies for different types of RD&E projects. They concluded that ‘‘metrics that are best for one type of activity may be counter-productive for another type’’ (p. 38) and warned that ‘‘if a firm applies the same metrics throughout the RD&E process it does not get the most out of its technological efforts’’ (p. 33). The use of the threetier metaphor by the researchers above highlights the fact that metrics or evaluative criteria should be aligned to the different objectives and therefore to the different requirements of each type. However, Hauser and Zettelmeyer [23] examined only the use of metrics for different types of RD&E processes and not at different gates of the process. Nevertheless, ‘‘most firms had a concept that the management of technology varied depending on the stage of the process’’ (p. 33). Our study has been developed to address this level of detail. Drawing on the foregoing review of the relevant literature, our specific research questions that guided our study were as follows: (1) Which criteria are used most frequently at the NPD evaluation gates? (2) Which evaluative dimensions are used most frequently at the NPD evaluation gates? We assessed the results for these two research questions in two separate countries to examine the stability of the findings. Moreover, we were interested in exploring how a firm’s profile was related to the nature and number of criteria and dimensions used at the NPD gates. Specifically, we examined firm-level factors (firm size, market share position, and NPD driver), NPD program level factors (innovation strategy and product newness), and respondent factors (experience in the firm and functional background). J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 25 Research Method Our research findings are based on a survey of 166 managers from Dutch and UK companies that are developing and manufacturing industrial goods. This research instrument was used to collect information on criteria that companies use at various evaluation gates in the NPD process. In addition, the survey collected background and demographic data on the respondent and the firm. The survey was pretested in two rounds (with four companies in each round). Interviews with six managers after the second round indicated that the meanings of the questions and answer categories were clear and that the survey could be completed without difficulties. The questionnaire originally was developed in Dutch for data collection in The Netherlands and subsequently was translated by a native speaker in English (and was back-translated by a different translator in Dutch as a check) for data collection in the UK. The procedure of collecting the data was identical in both countries. All potential respondents were prenotified by phone by one of the project members. They introduced themselves as contributors to an international study on NPD evaluation criteria. Preliminary notification by phone was used to solicit cooperation, to check whether the company had developed and launched any new products recently, to identify the respondent who had been responsible for the NPD effort, and to increase the response rate [39]. Accordingly, questionnaires were mailed out to those identified as having primary responsibility for NPD in each firm, by name. More details on the data collection in the two countries are provided below. The Netherlands. We used a CD-ROM Business Directory (by Generator BV) to develop a sample frame of 1,927 manufacturing companies with more than 20 employees in some selected industries (chemicals, medical equipment, electronics, and computers). From a total of 509 randomly selected companies contacted by phone, 228 companies agreed to participate in the research and received the mail questionnaire. Thirty-four companies had not developed any new products in the last five years; 134 companies only assembled or sold new products but did not develop them; 52 companies were not interested in participating in the research; and 61 of the companies could not be reached or had gone bankrupt. This procedure and an additional reminder postcard led to 134 usable questionnaires, an effective response rate of 59 percent (of those who agreed to 26 J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 S. HART ET AL. Table 1. Profile of Dutch and UK Samples The Netherlands Number Percent United Kingdom Number Total Sample Percent Number Percent Firm level factors Number of Employees Less than 50 32 33 4 6 36 22 51 to 100 29 30 8 12 37 22 101 to 1000 34 35 43 62 77 46 More than 1000 2 2 14 20 16 10 1 26 27 22 32 48 29 2–4 50 53 35 51 85 52 5 or Lower 19 20 12 17 31 19 Market driven 80 84 50 72 130 79 Technology driven 15 16 19 28 34 21 Market Share Position NPD Driver NPD Program level factors Innovation Strategy Technological innovator 47 49 39 57 86 52 Fast imitator 38 39 16 23 54 33 Cost reducer 12 12 14 20 26 16 Line addition 16 17 23 33 39 24 Improvement 65 67 42 61 107 64 Completely new 16 17 4 6 20 12 NP Newness Respondent factors Duration of Employment Less than 1 year 8 8 5 7 13 8 1 to 3 years 11 11 12 17 23 14 3 to 5 years 17 18 13 19 30 18 More than 5 years 61 63 39 57 100 60 1 new product 10 10 6 9 16 10 2–4 new products 43 44 30 43 73 44 5–9 new products 19 20 19 28 38 23 More than 10 25 26 14 20 39 23 Number of NPD Projects Involved Functional Area of Respondent Marketing/sales 16 17 43 62 59 36 R&D/development 57 59 11 16 68 41 General management 19 20 12 17 31 19 Other 4 4 3 4 7 4 INDUSTRIAL COMPANIES’ EVALUATION CRITERIA IN NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT GATES participate). We checked the responses from early and late respondents to assess nonresponse bias [1]. No significant differences were found between both sets of respondents thus minimizing concerns for nonresponse bias. To obtain a homogeneous sample of respondents, we will use only the responses from the companies who developed and launched new products for industrial customers (N597). Table 1 contains the profile of the Dutch sample. United Kingdom. We used the FAME CD-ROM Business Directory (by Bureau van Dyke) to develop a sample frame of 500 manufacturing companies with more than 20 employees in the same selected industries (chemicals, medical equipment, electronics and computers). From this original sample frame of 500 firms, after initial contact by phone, 48 were excluded because of a policy of company confidentiality. A further 14 had not been engaged in any NPD efforts and therefore were excluded. Of the remaining 438 respondents that agreed to participate, 100 returned the questionnaire, thus providing a response rate of 23 percent. Again, nonresponse bias was examined and was not found to be a major problem [1]. To also obtain a homogeneous sample of UK respondents, only the responses from industrial companies were included (N569). Table 1 also provides an overview of the UK sample. Questionnaire. The questionnaire focused on the 15 core project-level indicators of new product performance [18,19]. Since Griffin and Page [18,19] were mainly interested in measuring new product performance after launch, we also scanned the literature for criteria that are used in earlier gates of the NPD process. Five additional criteria were identified: product uniqueness, market potential, marketing chance, technical feasibility, and intuition [2,11,15,26,32]. By comparing seven models of the NPD process [4,6,9,13,25,30,36], six distinct evaluation gates were selected: idea screening, concept screening, business analysis, product testing, analyzing test market results, and after-launch assessment. Hultink and Robben [24] made a distinction between measuring new product performance in the short term and in the long term after launch. They found that the importance attached by managers to the indicators of new product performance depended strongly on this time perspective. Therefore, we decided to include the short-term as well as the long-term performance assessment. Hence, for each of the seven evaluation gates, respondents assessed which of the 20 evaluation J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 27 criteria were used. Respondents were asked to answer the questions in relation to representative new products that they had developed and had launched in the previous five years. The ability of the respondents to provide well-informed answers to these questions was checked by means of the number of NPD projects they were involved in the previous five years as well as by the duration of their employment with the firm. It was found that 90 percent of the respondents were involved with the development of more than two new products during the previous five years and that 78 percent of them had been with the firm for more than three years (see Table 1). These findings increased our confidence in the ability of the respondents to provide wellinformed answers regarding their firms and associated NPD practices. Respondents received, along with the questionnaire, detailed definitions and a diagrammatic representation of the NPD stages and evaluation gates. These definitions and diagram were pretested with six respondents in four different companies, increasing the face validity of our instrument as it communicated a consistent picture of NPD stages and gates across the respondents. The pretest showed that it was not necessary to provide definitions for the 20 evaluation criteria, as the respondents felt comfortable with the criteria as stated and considered that definitions for the criteria were superfluous and even distracting. Analysis and Results This section consists of three parts. First, the most frequently used evaluation criteria at the seven NPD gates will be presented. Then, we will focus on the patterns of use of various evaluative dimensions. Finally, we will test whether any differences exist with regard to the evaluative dimensions used per NPD gate for different subgroups of respondents. Evaluation Criteria at NPD Gates For those respondents who said they evaluated the new product in a certain gate, we calculated the percentage of those firms that used any of the 20 evaluation criteria. Table 2 shows the results from this analysis; shadowed boxes include the percentage of firms that exceeds our cut-off point of 50 percent, indicating what we regard as the most 28 J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 S. HART ET AL. Table 2. Percentage of Companies Using Evaluation Criteria at NPD Gates Marketing Chance Technical Feasibility Intuition 51 Market Potential 19 Product Uniqueness 8 Time-to-Market 27 Quality 5 Product Performance 24 Introduced in Time 11 Stays within Budget 38 Margin IRR/ROI 31 Profit Objectives 27 Break-Even time 24 Sales in Units 31 Market Share 46 Sales Growth Idea Screening Sales Objectives NPD Evaluation Gates Customer Satisfaction Evaluation Criteria Customer Acceptance The Netherlands 36 17 51 52 28 70 54 Concept Screening 48 37 11 1 4 14 6 10 9 8 9 14 48 36 9 18 22 14 47 20 Business Analysis 31 22 51 38 37 62 27 46 26 46 16 22 25 18 20 20 50 39 27 20 Product Testing 36 37 6 2 5 22 11 9 6 16 39 34 65 67 21 28 10 6 36 20 Test Market 68 66 9 7 12 24 8 12 8 16 17 29 63 56 18 23 19 17 43 19 Post-Launch S/T 54 59 41 28 33 59 15 41 19 44 12 32 45 35 14 26 35 22 8 16 Post-Launch L/T 31 52 38 42 36 51 7 38 17 40 10 9 31 23 4 14 27 13 3 13 United Kingdom Customer Acceptance Customer Satisfaction Sales Objectives Sales Growth Market Share Sales in Units Break-Even time Profit Objectives IRR/ROI Margin Stays within Budget Introduced in Time Product Performance Quality Time-to-Market Product Uniqueness Market Potential Marketing Chance Technical Feasibility Intuition Evaluation Criteria Idea Screening 54 38 46 27 27 27 11 32 16 35 19 14 33 22 35 75 73 40 75 62 Concept Screening 60 45 20 10 10 23 10 15 8 23 25 22 45 32 23 42 53 35 70 28 Business Analysis 31 25 60 52 55 70 42 67 67 73 31 31 27 22 46 36 69 48 33 19 Product Testing 45 39 20 14 13 16 13 20 16 27 59 45 73 69 47 42 30 17 59 19 Test Market 77 66 27 16 16 20 16 20 17 25 33 41 83 79 36 36 38 19 48 11 Post-Launch S/T 77 75 70 64 52 71 32 57 29 71 16 43 54 61 32 32 36 23 9 14 Post-Launch L/T 57 76 68 72 74 68 28 72 47 79 6 13 55 64 0 30 32 17 8 8 NPD Evaluation Gates frequently used NPD evaluation criteria. As expected, some criteria were used more often in the early gates of the NPD process (for example, technical feasibility and intuition), while other criteria were more often used in later gates of the process (for example, sales in units, meeting profit objectives and margin). Some criteria were frequently used in only one or two of the evaluation gates (for example, intuition and product uniqueness), while other criteria were frequently used in at least three of the seven evaluation gates (for example, customer satisfaction, sales in units and product performance). Below, we will discuss the three most frequently used criteria at the different NPD evaluation gates (see Table 3). Idea screening. Technical feasibility is the most frequently used criterion for idea screening purposes. Intuition also plays a major role (see Table 2). This is INDUSTRIAL COMPANIES’ EVALUATION CRITERIA IN NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT GATES J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 29 Table 3. Most Frequently Used Evaluation Criteria at NPD Gates The Netherlands Indicator United Kingdom Percent of use Indicator Percent of use Idea Screening Technical feasibility 70 Technical feasibility 75 Intuition 54 Product uniqueness 75 Market potential 52 Market potential 73 Customer acceptance 48 Technical feasibility 70 Product performance 48 Customer acceptance 60 Technical feasibility 47 Market potential 53 Concept Screening Business Analysis Sales in units 62 Margin 73 Sales objectives 51 Sales in units 70 Market potential 50 Market potential 69 Quality 67 Product performance 73 Product performance 65 Quality 69 Stays within budget 39 Stays within budget 59 Product Testing Analyze Test-Market Results Customer acceptance 67 Product performance 73 Customer satisfaction 65 Quality 69 63 Customer acceptance 59 Product performance Post Launch Evaluation, Short Term Customer satisfaction 59 Customer acceptance 77 Sales in units 59 Customer satisfaction 75 Customer acceptance 54 Sales in units 71 Post Launch Evaluation, Long Term Customer satisfaction 52 Margin 79 Sales in units 51 Customer satisfaction 76 Sales growth 42 Market share 74 not surprising given the large uncertainties and the lack of relevant, valid information at this stage. In addition, market potential and product uniqueness are assessed. It seems that firms in our sample follow a balanced approach at this gate by evaluating both technical and market aspects of new ideas. Concept screening. Table 3 shows that firms most frequently used customer acceptance, product performance, and technical feasibility at this gate. UK companies also test the market potential of the new product concept. Of interest is the lack of use of any financial criteria in the first two evaluation gates of the NPD process. Business analysis. After the business analysis is performed, large investments are needed to proceed to the next stage of the NPD process. Hence, it is critical to forecast the sales and profit levels for the proposed new product. Accordingly, in the business analysis gate, companies tend to use sales criteria (such as sales in units) instead of product-level criteria. Market potential also figures heavily, as there is a clear association between sales and market potential. UK companies also evaluate the product’s margin extensively. Product testing. After the product development stage, it is of paramount importance to check whether the new product has met its objectives from a technical point of view. To prevent ‘‘technical dogs’’ from being developed [5], not surprisingly, the most frequently used criteria in this stage have to do with 30 J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 product performance and quality. Firms also are keen to measure whether they stay within the development budget at this gate. Analyze test market results. After the market testing stage in the NPD process, companies measure the performance and quality of the new product again. In addition, customer reactions to the new product are collected. By evaluating technical aspects as well as customer acceptance and satisfaction, companies apparently try to prevent launching ‘‘better mousetraps that nobody wants’’ [5]. Post-launch evaluation short term. This gate is the first real test for the new product in the market. Now it becomes clear whether the product will be accepted in the marketplace and whether any profit will be made on the new product investments. In addition, it is the market launch stage where positive or negative word of mouth owing to customer satisfaction can build or break the new product’s success. Hence, the most frequently used evaluation criteria measure the customer acceptance of the new product, customer satisfaction, and sales levels. Post-launch evaluation long term. At this time the new product should be well established in the marketplace. Initial problems to the new product have been sorted out. Performance now is assessed mainly in terms of sales and market share. However, it is interesting to note that customer satisfaction also is being assessed in this gate. This, we argue, is important since according to Woodruff [38] changes in customer expectations may influence the level of satisfaction they get from a product. Firms, therefore, need to be alert to detect such changes, which, if surpassed, may undermine their competitive position. Firms in the UK also frequently measure the new product’s margin at this gate. Evaluative Dimensions at NPD Gates To address research question 2, our objective was to move away from single criteria and examine what is happening in a broader context—for example, do companies show a usage preference of some evaluative dimensions over others at different gates in the NPD process? As mentioned earlier, the 20 criteria used in our study correspond to the 15 project-level criteria identified by Griffin and Page [18,19] and include five more because our study examined the entire range of the NPD process and not just after-launch performance. In the present step of our analysis, we used S. HART ET AL. Griffin and Page’s [18] three dimensions of performance (market acceptance, financial performance, and product performance), as well as the additional indicators we introduced in a category of their own (additional indicators). Table 4 presents the results of this analysis. Each cell in Table 4 depicts the number of evaluation criteria (from each of the four dimensions) used per NPD gate. The total average number of criteria for each dimension used throughout the entire process is shown (column totals) as is the total average use of criteria for each dimension per stage (row totals). Furthermore, all are broken down for the Dutch and UK sample and statistical significance of differences tested using t-tests. Table 4 shows that the market acceptance dimension permeates all the evaluation gates in the NPD process, indicating the market orientation of these firms. The financial dimension emerges prominently only during the business analysis evaluation and after market launch in the short and long term. The product performance dimension, despite figuring in almost every evaluation gate, becomes prominent during the product testing and test market evaluation gates. Finally, our dimension containing additional criteria shows a fair use over the entire range of the NPD evaluation gates yet with prominence during the idea-screening gate. These results are consistent for both countries in which we collected our data. In fact, only six (out of 29) tests between the two countries appeared to be statistically significant (see Table 4). We proceeded to examine the emerging patterns in evaluative dimensions over the NPD evaluation gates. Figure 1 presents four graphical representations of the number of criteria used per dimension over the NPD evaluation gates. Examining this figure, it becomes apparent again that the two country samples show a similar pattern of usage, although firms in the UK generally use more criteria, an observation strengthened by the fact that one of the six statistically significant differences between the two countries was the total average number of criteria used for each stage throughout over the entirety of the evaluative gates. Finally, in order to compare the relative usage of the four dimensions over the NPD evaluation gates, we calculated the standardized number of criteria per dimension used in each evaluation gate (i.e., number of criteria per dimension used divided by the number of criteria in each dimension). Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the results of this analysis. INDUSTRIAL COMPANIES’ EVALUATION CRITERIA IN NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT GATES J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 31 Table 4. Number of Criteria per Evaluative Dimension at the NPD Gates Market Acceptance Financial Performance Product Performance Additional Indicators Total Market Acceptance Financial Performance Product Performance Additional Indicators Total Evaluation Dimensions Idea Screening 2.0 0.7 1.3 2.5 6.5 2.2 0.9 1.2 3.2 7.6 Concept Screening 1.2 0.3 1.2 1.2 3.9 1.7 0.6 1.5 2.3 6.1 Business Analysis 2.4 1.5 1.0 1.6 6.5 2.9 2.5 1.6 2.1 9.0 Product Testing 1.1 0.4 2.3 1.3 5.1 1.5 0.8 2.9 1.7 6.9 Test Market 1.8 0.4 1.8 1.2 5.3 2.2 0.8 2.7 1.5 7.2 Post-Launch S/T 2.7 1.2 1.4 1.1 6.4 4.1 1.9 2.1 1.1 9.2 Post-Launch L/T 2.5 1.0 0.8 0.7 5.0 4.1 2.3 1.4 0.9 8.7 13.71 5.58 9.8 9.62 38.71 18.7 9.8 13.4 12.8 54.7 NPD Evaluation Gates Total Average 5.53 7.8 Note: Entries in bold indicate a significant difference in the number of criteria used per dimension between The Netherlands and the UK. We adjusted the a level for the number of tests. For all significant differences, means were higher for the UK. The pattern of relative usage of the evaluative dimensions over the NPD gates was identical in both countries. Figure 2 therefore shows the relative usage of these dimensions for the total sample. Our set of additional indicators, which included criteria such as product uniqueness, technical feasibility, and intuition, is used most frequently at the idea and conceptscreening gates. Then, the financial performance and market acceptance dimensions take over at the business analysis gate. Assessing product performance dominates the product testing and test-market gates during which the financial performance dimension is largely ignored. The fact that financial performance hardly is assessed at the test-market gate is somewhat surprising, as it suggests that only the functional performance and market acceptance are assessed without their attendant financial implications. Thereafter however, the market acceptance and financial performance dimensions resume their primacy over the other dimensions as the NPD process draws nearer to its conclusion. Patterns of usage in Figure 2 corroborate our earlier findings and provide support to the work of Ronkainen [32] and Hultink and Robben [24]. Indeed, the latter authors found that the importance of financial criteria is increased in the long-term assessment of NPD success. The usage pattern of financial criteria in Figure 2 supports this variation that also is evident in Ronkainen’s [32] work. However, whereas Ronkainen [32] found that market acceptance criteria scored lower in usage than financial performance criteria in the concept-screening gate, our findings suggest a different pattern. Figure 2 shows that market acceptance criteria score consistently is higher than financial criteria in every evaluation gate apart from the business analysis evaluation. As explained earlier, this may be an indication of the higher market orientation of firms in our sample as compared to those studied by Ronkainen [32] in 1985. This would be consistent with the development in the last decade of the concept of market orientation, which might be expected to filter into numerous management practices, including the evaluative dimensions of the NPD process, producing a stronger emphasis on market reaction as a primary indication of the ‘‘green light’’ throughout the development process. Given the paucity of previous empirical research on the evaluation gates in NPD, looking at what might account for different usage of evaluative dimensions may lead to greater insights as to when and why some dimensions should be deployed. We 32 J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 S. HART ET AL. Number of Criteria Country Variations in Market Acceptance 6. 0 5. 0 4. 0 3. 0 2. 0 1. 0 0. 0 Netherlands U.K. Idea Screening Concept Screening Business Analysis Product Testing Test Market Post-Launch S/T Post-Launch L/T NPD Evaluation Gates Number of Criteria Country Variations in Financial Performance 4. 0 3. 0 Netherlands 2. 0 U.K. 1. 0 0. 0 Idea Screening Concept Screening Business Analysis Product Testing Test Market Post-Launch S/T Post-Launch L/T NPD Evaluation Gates Number of Criteria Country Variations in Product Performance 5 .0 4 .0 3 .0 Netherlands 2 .0 U.K. 1 .0 0 .0 Idea Screening Concept Screening Business Analysis Product Testing Test Market Post-Launch S/T Post-Launch L/T NPD Evaluation Gates Number of Criteria Country Variations in Additional indicators 5.0 4.0 3.0 Netherlands 2.0 U.K. 1.0 0.0 Idea Screening Concept Screening Business Analysis Product Testing Test Market Post-Launch S/T Post-Launch L/T NPD Evaluation Gates Figure 1. Number of Evaluation Criteria Used per Dimension over the NPD Gates therefore decided to investigate the impact of the sample profile variables to examine the stability of the patterns of evaluation. The Impact of Profile Variables on the Evaluative Dimensions Used Three sets of profile variables were analyzed for evidence of changing patterns of evaluation. These profile variables included firm-level factors (size, market share position, and NPD driver), NPD program level factors (innovation strategy and product newness), and respondent factors (experience and functional background). Table 5 shows the number of significant differences (out of 28 tests) for each of these sets of factors. The tests used were either t-tests or one-way analysis of variance, depending upon the number of groups used to describe the profile variables (see Table 1). Of the firm-level factors, only one difference among firms of different sizes was found to be significant statistically: At the business analysis stage, larger firms used more product performance criteria than the smallest companies in the sample. This, however, may be a chance finding. In addition, firms with different market share positions tended to use the same INDUSTRIAL COMPANIES’ EVALUATION CRITERIA IN NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT GATES J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 33 Standardized Number of Criteria per Dimension Variations in Performance Dimensions over NPD Evaluation Gates 0.6 0.5 Market Acceptance Financial Performance Product Performance Additional Indicators 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0.0 Idea Concept Screening Screening Business Analysis Product Test Market Post-Launch Post-Launch Testing S/T L/T NPD Evaluation Gates Figure 2. Relative Use of Evaluative Dimensions over NPD Gates (for total sample) number of criteria per dimension, and when the sample was subdivided into those firms that were technologically driven and those that were market driven, again the number of criteria used for each evaluative dimension showed no change. Similarly, when we examined the NPD program-level factors, no differences in the number of evaluation criteria per dimension were found. Table 5. Differences in Number of Criteria Used per Dimension across Subgroups* Number of Differences Profile Variables (Out of 28 tests) Firm-Level Factors Number of employees 1 Market share position 0 NPD driver 0 NPD Program-Level Factors Innovation strategy 0 Product newness 0 Finally, when looking at the respondent factors, the number of evaluation criteria used per dimension did not fluctuate with different levels of respondent expertise. A slight difference was found in four (out of 28) tests with respect to the functional area of the respondent. Specifically, at the idea-screening gate, marketing/sales respondents used more market acceptance criteria than research and development (R&D) respondents. At the concept-screening gate, marketing/sales respondents used more criteria for the product performance dimension, while at the product testing and long-term post-launch evaluations marketing/sales respondents used more of the additional criteria. The number of differences, however, is so low that we cannot be sure that they are not merely chance results. Overall, given the vast number of tests that were insignificant, we have no strong evidence in support of firm size, market position, NPD program type, or allegiances of the respondents being significant moderators of any variations in the evaluative dimensions used at different gates of the NPD process. That said, the results hint that there may be a preference for using evaluative dimensions consistent with the traditions and training of one’s professional functional area, and overall, measurement is more intense in the UK than in the Netherlands. Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations Respondent Factors Duration of employment 0 Experience in NPD 0 Functional area 4 It is agreed widely that the notion of complexity is inherent in the NPD efforts of industrial companies. However, it is agreed equally that this complexity can and should be managed for the successful development of new products. One means of doing so is by 34 J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 establishing guideposts against which management activity can be evaluated, controlled, and modified if needed throughout the NPD process. The significance of the latter becomes apparent if one considers the ever increasing costs of NPD and the detrimental effects to the firms’ resources if they commit to the wrong project. Research in the past has outlined a number of criteria used by firms to evaluate new product projects. Research also has demonstrated that as these projects progress, they impose different requirements to the firm’s management and its operational resources. Therefore, it is logical to assume that the evaluative criteria used per gate of the NPD process should reflect the different tasks and competencies required at the corresponding stages. Yet evidence in support of this assumption is only scant, thus producing an incomplete picture of the NPD measuring processes in industrial firms. The present study aimed to fill a part of this gap in extant knowledge. Our findings first show that companies use different criteria at different NPD evaluation gates. While such criteria as technical feasibility, intuition, and market potential are stressed in the early screening gates of the NPD process, a focus on product performance, quality, and staying within the development budget are considered of paramount importance after the product has been developed. Customer acceptance and satisfaction and unit sales are primary considerations during and after market launch. Our study also produced interesting patterns of usage of evaluative dimensions over the NPD process. The market acceptance dimension permeates the entire NPD process and gains in prominence during the short- and long-term performance evaluation after launch. As we argued earlier, this may be attributed to the continuous attention to customer acceptance and satisfaction paid by the firms in our sample. From a theoretical point of view this is noteworthy, as marketing theory always has advocated in favor of a continuous orientation to the needs of the customer [29]. Furthermore, the fact that this orientation permeates the whole NPD process is a first indication that despite specific considerations at each stage (e.g., conceptual, technical, financial, and market), firms attempt to impose an overall layer of customer and marketing orientation. We speculate that this may enable them to listen and react to the ‘‘voice of the customer’’ in a systematic and coherent way alongside the whole spectrum of their NPD efforts. S. HART ET AL. The financial dimension emerges prominently in the business analysis gate and gains importance in the short- and long-term performance evaluation after launch. Again, use of this dimension corresponds to the requirements of the specific stage. Evaluation criteria of a financial nature may assist management to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of their efforts and to identify whether their products need additional support, a rejuvenating injection of capital or a strategy of deletion to give way to other products or release resources for other NPD projects. As expected, the product performance evaluative dimension figures strongly in the product and market testing gates. This, we suggest, reflects management efforts to avoid go-errors that have to do with the launch of ‘‘technical dogs’’ or ‘‘better mousetraps no one wants’’ [5]. Our set of additional criteria proved to be especially relevant in the idea-screening gate. Consideration of product uniqueness, market potential, and technical feasibility at the early stages of the NPD project reflects, we argue, a tendency of our sampled firms to follow a balanced yet holistic approach in their NPD efforts. From a managerial point of view, the above patterns may provide useful guidelines for focusing attention and expending resources during the entire NPD process. We argue that the informed use of evaluation criteria as guideposts for increased managerial attention and identification of problems may help management to prevent drop- and go-errors in their innovation efforts. Managers may compare and contrast findings from this study with their own NPD practices and, by doing so, may enrich the knowledge pool upon which they draw to make well-informed decisions. We suggest that, among other things, three key issues emerged for managers. First, we recommend that managers should strive to develop and to implement evaluative criteria targeted to the specific requirements and expectations from each stage of their NPD project. This, we argue, will allow them to detect problems and to identify opportunities as they occur. Moreover, although not considered in this article, carefully focused evaluative criteria allow management to allocate responsibility and to exercise control that reflects managerial fairness and justice. Second, we recommend that managers should ‘‘listen to the voice of the customer’’ throughout their NPD process. This can be accomplished by evaluating each stage of their NPD process, among other things, with customer acceptance and customer INDUSTRIAL COMPANIES’ EVALUATION CRITERIA IN NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT GATES satisfaction in mind. Of course, as suggested earlier, management should consider evaluative criteria that are aligned to the requirement and expectations of each stage, yet customer acceptance and satisfaction emerged as evaluative criteria with high usage along the whole spectrum of NPD activities in our sampled firms. Third, it was interesting to find that the pattern of evaluative dimensions used over the NPD gates was similar across subgroups of respondents. Although the present study did not include all possible relevant firm-level, NPD-program level, and respondent factors, those mentioned frequently in the literature were investigated. These findings suggest that it is not important how large the company is, what their market share position is, what the driver of NPD is, what innovation strategy they follow, and what kind of new products they develop. All firms likely should measure their NPD processes (in terms of the evaluative dimensions) in a pattern consistent with the one found for our samples to assess the attractiveness of new product opportunities at different stages of development. Limitations and Further Research Directions This research project has helped define better the complexity and structure of NPD measuring processes in industrial firms. However, as with all research, the methods employed have inherent limitations, which lead to opportunities to improve future research in this area. First, we asked respondents to answer the questions in relation to representative new products they had developed and had launched in the previous five years. This retrospective methodology has several limitations. For example, halo bias effects may be present because the performance of the new products chosen was known prior to completing the survey. There also may be differences between respondents’ recalled and actual measurements. For example, selectivity of recall, rationality bias, and reconstruction bias may cause respondents to bias upwardly their responses in order to make their firms look good. Second, this research investigated the use of criteria across several NPD evaluation gates. An obvious next step would be to measure the perceived importance of the criteria at the different evaluation gates. Although it may be suggested that the frequency of use of a J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 35 certain criterion reflects, or is related to, the importance of measuring this criterion, additional research is necessary to substantiate this. A third limitation is that this research is based on what managers reported that they have done. Thus, the research is descriptive, providing insight only into the number and nature of criteria used at the evaluation gates. While this is useful, it would be even more helpful if we could tell them what to do. For example, by contrasting successful with unsuccessful firms, or successful with failed new products, differences may appear in the criteria that are used at the evaluation gates. The striking similarities that were identified in our results across subgroups of respondents may indicate that heterogeneity of samples in research investigating NPD evaluation criteria need not bias the results. However, we also suggest using alternative lenses for detecting any differences or similarities in the use of NPD evaluative criteria. For example, an analysis comparing emerging (new economy) with traditional sectors (old economy) may produce additional insights to this subject. Also, we suggest that in line with our earlier discussion, one would expect differences in the use of evaluative criteria on the basis of differences on strategic objectives set or other situational and environmental conditions surrounding particular NPD projects. For example, researchers should examine whether time pressures and hostile competitive environments moderate both the number and relative importance of evaluative criteria used per stage of the NPD process. The type of the NPD project may call for the use of additional evaluative criteria as in the work of Hauser [22]. Also, collaborative NPD projects may require development and implementation of different evaluation criteria. Furthermore, differences in the number of criteria used by Dutch and UK companies deserve further attention. Country variations in the average size of firms and the functional background of the respondents in our sample suggest that there may be value in research seeking to assess if such variations may moderate the number of evaluation criteria used at different gates of the NPD process. Finally, as evaluative criteria may reflect areas where managerial attention is directed, one can expect a link between evaluative criteria used and strategic and operational capabilities of the firm. Researchers examining this link may find an excellent opportunity for integrating strategic concepts into the theory and practice of NPD. Overall, results of this project 36 J PROD INNOV MANAG 2003;20:22–36 S. HART ET AL. increase the current state of knowledge with regard to the pool of criteria used by management to safeguard the success of their NPD efforts. The significance of the latter can be outlined by referring to Cooper and Kleinschmidt [10] who stated, ‘‘If businesses are to survive and prosper, managers must become astute at selecting new product winners, and at effectively managing the process from idea to launch.’’ 22. Hart, S. and Baker, M. Learning from success: multiple convergent processing in new product development. International Marketing Review 11(1):77–92 (1994). References 23. Hauser, J.R. Research, development, and engineering metrics. Management Science 44:1670–1689 (1998). 1. Armstrong, J.S. and Overton, T.S. Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research 14(August):396– 402 (1977). 2. Balachandra, R. Critical signals for making go/no-go decisions in new product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management 1(2):92–100 (1984). 3. Biemans, W.G. Managing Innovation within Networks. London and New York: Routledge, 1992. 4. Booz, Allen and Hamilton New Products Management for the 1980s. New York, NY: Booz, Allen & Hamilton, 1982. 5. Calantone, R.J. and Cooper, R.G. A discriminant model for identifying scenarios of industrial new product failure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 7(3):163–183 (1979). 6. Cooper, R.G. Stage-gate systems: a new tool for managing new products. Business Horizons (May–June): 44–54 (1990). 7. Cooper, R.G. Winning at New Products: Accelerating the Process from Idea to Launch. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1993. 8. Cooper, R.G. and de Brentani, U. Criteria for screening new industrial products. Industrial Marketing Management 13:149–156 (1984). 9. Cooper, R.G. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. An investigation into the new product process: steps, deficiencies, and impact. Journal of Product Innovation Management 3:71–85 (1986). 19. Griffin, A. and Page, A.L. PDMA’s success measurement project: recommended measures by project and strategy type. Journal of Product Innovation Management 13:478–496 (1996). 20. Griffin, A. The PDMA Best Practice Report, PDMA (1997). 21. Hart, S. Dimensions of success in new product development: an exploratory investigation. Journal of Marketing Management 9:23– 41 (1993). 24. Hauser, J.R. and Zettelmeyer, F. ‘‘Metrics to evaluate RD&E. Research-Technology Management 40:32–38 (1997). 25. Hultink, E.J. and Robben, H.S.J. Measuring new product success: the difference that time perspective makes. Journal of Product Innovation Management 12:392–405 (1995). 26. Kotler, P. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation and Control, (7th edition). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1991. 27. Lipovetsky, S., Tishler, A., Dvir, D. and Shenhar, A. The relative importance of project success dimensions. R&D Management 27(2):97–106 (1997). 28. Mahajan, V. and Wind, J. New product models: practice, shortcomings, and desired improvements. Journal of Product Innovation Management 9(2):128–139 (1992). 29. Moenaert, R.K. and Souder, W.E. An information transfer model for integrating marketing and R&D personnel in NPD projects. Journal of Product Innovation Management 7(2):91–107 (1990). 30. Narver, J.C. and Slater, S.F. The effect of marketing orientation on business performance. Journal of Marketing 54(October):20–35 (1990). 31. Page, A.L. Assessing new product development practices and performance: establishing crucial norms. Journal of Product Innovation Management 8:18–31 (1993). 10. Cooper, R.G. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. Success factors in product innovation. Industrial Marketing Management 16:215–223 (1987). 32. Rochford, L. and Rudelius, W. How involving more functional areas within a firm affects the new product process. Journal of Product Innovation Management 9(4):287–299 (1992). 11. Craig, A. and Hart, S. Where to now in new product development research. European Journal of Marketing 26:1–49 (1992). 33. Ronkainen, I.A. Criteria changes across product development stages. Industrial Marketing Management 14:171–178 (1985). 12. Crawford, C. Merle Defining the charter for product innovation. Sloan Management Review (Fall): 3–12 (1980). 34. Saren, M.S. Reframing the process of new product development: from stages models to a blocks. Journal of Marketing Management 10(7):633–644 (1994). 13. Crawford, C.M. New Product Management. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin, 1994. 14. De Brentani, U. Do firms need a custom-designed new productscreening model? Journal of Product Innovation Management 3:108–119 (1986). 15. Feldman, L.P. and Page, A.L. Principles versus practice in new product planning. Journal of Product Innovation Management 1:43–55 (1984). 35. Schmidt, J.B. and Calantone, R.J. Are really new product development projects harder to shut down? Journal of Product Innovation Management 15(March):111–123 (1998). 36. Takeuchi, H. and Nonaka, I. The new product development game. Harvard Business Review (Jan:–Feb:) 137–146 (1986). 37. Urban, G.L. and Hauser, J.R. Design and Marketing of New Products. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993. 16. Gehani, R.R. Concurrent product development for fast-track corporations. Long Range Planning 25(6):40–47 (1992). 38. Wind, J. and Mahajan, V. Issues and opportunities in new product development. Journal of Marketing Research 34:1–12 (1997). 17. Griffin, A. Metrics for measuring product development cycle time. Journal of Product Innovation Management 10(2):112–125 (1993). 39. Woodruff, R.B. Customer value: the next source for competitive advantage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 25(2):139–153 (1997). 18. Griffin, A. and Page, A.L. An interim report on measuring product development success and failure. Journal of Product Innovation Management 10:291–308 (1993).

![Your [NPD Department, Education Department, etc.] celebrates](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006999280_1-c4853890b7f91ccbdba78c778c43c36b-300x300.png)