CARLEEN GRUNTMAN

TOWARDS THE MEANING OF FOR: A CORPUS

ANALYSIS

Thèse présentée

à la Faculté des études supérieures de l'Université Laval

dans le cadre du programme de doctorat en linguistique

pour l'obtention du grade de Philosophiae Doctor (Ph.D.)

DEPARTEMENT DE LANGUES, LINGUISTIQUE ET TRADUCTION

FACULTÉ DES LETTRES

UNIVERSITÉ LAVAL

QUÉBEC

2011

© Carleen Gruntman, 2011

Abstract

The present study is an attempt to determine whether there is a core meaning,

or potential meaning, that determines the 31 main uses of the preposition for in

discourse. The theoretical approach adopted is based on Gustave Guillaume's general

theory of the Psychomechanics of Language in which it is postulated that, even for a

word that appears to be highly polysemous, it is possible to hypothesize one meaning

that explains all observed usage. In order to formulate an explanation regarding the

meaning oi for, an analysis of authentic texts was carried out, in addition to giving

careful consideration to the explanations and descriptions found in grammars and

dictionaries. The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) and the British

National Corpus (BNC) provided most of the authentic texts analyzed for this study.

The actual observation of for in these corpora involved grouping the corpus examples

according to common collocations, primarily of the various types of verbal lexemes

found with for, and then determining whether a common semantic element could be

ascertained in the co-lexemes of for which determined their occurrence with this

preposition. Further insights were provided by observing the types of noun phrases

that occur after for, particularly with verbs of movement, and contrasting these

observations with the data found with the same verbs when construed with the

semantically related preposition to.

As well, from a diachronic perspective, it was

necessary to consider how for developed from a limited use, possibly involving one

single sense, into a wide variety of multiple senses, and whether or not this first sense

can contribute to a more unified explanation of modern-day usage of for. The position

taken in this thesis is that for contributes a meaning in all its uses, even in the so-called

complementizer function in for...to constructions where it implies future-oriented or

forward-looking directionality in the form of the ear-marking of an event for a

prospective subject. Fur's semantic contribution was also discerned in usage with verbs

expressing various forms of future orientation such as desire, request, effort or

purpose. After careful observation and analysis, it was hypothesized that for represents

a movement bringing into association two entities such that one entity comes to occupy

the space belonging to the other. When combined with contextual factors, this

unspecified potential can give rise to four main types of expressive effect, those of

exchange, attribution, obtaining and matching.

Ill

Résumé

Towards the Meaning of For. A Corpus Analysis

Les recherches présentées dans cette thèse portent sur la préposition anglaise

for. Ce mot jouit non seulement d'une haute fréquence d'emploi en anglais, mais

également d'un double statut, pouvant s'employer tantôt comme préposition, tantôt

comme conjonction. À cela s'ajoute les 31 sens différents qui peuvent lui être attribués

selon les contextes, d'où les nombreuses difficultés liées à l'enseignement de ce mot

dans le cadre de l'apprentissage de l'anglais langue seconde.

Cette étude vise à déterminer s'il existe un signifié de puissance unique qui

déterminerait en langue les divers emplois de for en discours. Elle s'inscrit dans le

cadre de la psychomécanique du langage. Il n'existe par ailleurs à ce jour aucune étude

de corpus sur le signifié du mot for. C'est pourquoi cette recherche s'appuiera sur une

analyse approfondie des emplois de ce mot à partir d'un corpus constitué de plus de

5,000 exemples attestés, tirés de la langue écrite et parlée, analyse qui sera effectuée

dans une perspective tant diachronique que synchronique.

Dans le débat en grammaire cognitive entre prototypicité et schématicité, cette

étude plaide en faveur d'un seul signifié schématique pour la préposition for, qui

nonobstant son caractère abstrait, conserve suffisamment de matière lexicale pour lui

éviter l'étiquette de signifié «délexicalisé».

IV

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the participation and essential

contribution of Professor Patrick Duffley, my thesis supervisor.

Not only did he

provide expert guidance, his patience went above and beyond the call of duty giving me

the freedom and time to complete this dissertation. For this I will be forever grateful.

As well, I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Walter Hirtle, always

encouraging, whose introduction to the study of language and especially the works of

Gustave Guillaume, ultimately sent me in pursuit of the ever, maybe forever, elusive for.

Dr. Barbara Bacz's careful reading of an earlier draft of this dissertation was

invaluable with respect to the rigours of academia. Her comments ultimately allowed

for a more cohesive and structured dissertation, thank-you.

I also remain grateful to Dr. John Hewson, member of my examination

committee, for his indispensable and significant comments.

As well, I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to all those friends and

family members, notably Ron and Pascale, whose encouragement and support kept me

on track, ultimately getting me to the finish line.

During my studies, I was honoured and grateful to be awarded a bursary from le

Fonds Gustave Guillaume. In addition, I am thankful for the financial support awarded

to me for professional development from the École des langues de l'Université Laval

and the Syndicat des chargées et chargés de cours de l'Université Laval.

Finally, this thesis is dedicated to Kay and Art, in memorandum, for they made it

all possible.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract

Résumé

Acknowledgments

Table of Contents

„

General Introduction

1. The Problem

2. Objectives

3. Corpus Methodology

3.1 Preliminary Remarks

3.2 The Corpus

3.3 Method of Analysis

3.4 Order of Presentation

Chapter 1: The Theoretical Framework

Introduction

The Theoretical Approach

Other Approaches

Defining Prepositional Meaning

4.1. A Cognitive Approach to Lexical Analysis

4.2 A Psychomechanical Approach to Prepositions....'.

5. Lexical Monosemy

6. Prepositions: Function Words?

7. Various Descriptions

1.

2.

3.

4.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Page

i

iii

iv

v

Chapter 2: For. A Diachronic Perspective

Preliminaries

Problems of Terminology

For, Fore, and Pro

Prepositional Development: Configurational Syntax

Recorded Dictionary Meanings: Old English to Modern English

Conclusion

Chapter 3: Complementizer or Preposition?

1. Preliminaries

2. For-To Complementizer Explained

2.1 Diachronic/or NP to V Construction

3. Characteristics of the For-Complement

3.1 Subject of the Infinitive

3.2 Other Characteristics

4. For Complementizer: Semantically Empty?

'

1

5

5

5

6

6

8

10

12

16

19

20

24

29

32

35

45

46

47

51

53

61

63

64

68

70

70

71

74

VI

4.1 Semantic Interpretations

4.2 Lindstromberg: A Prototypical Meaning

5. Verbal Matrix Predicates

6. Conclusion

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Chapter 4: Verbs Signifying Movement

Preliminaries

Data Organization and Analysis: Verbs of Movement

Verbs of Direction

3.1 To Go

3.2 To Arrive

3.3 To Depart

3.4 To Head

3.5 To Leave

3.6 To Return

3.7 To Come

3.8 To Set Out

3.9 To Set Off

3.10 To Set Sail

3.11 To Travel

Verbs of Manner-Specified Movement

4.17bi?un

4.2 To Crawl

4.3 To Walk

4.4 To Wander

4.5 To Stray

4.6 To March

4.7 To Fly

4.8 To Dash

4.9 To Rush

Verbs of Bodily Movement:

5.1 To Climb

5.2 To Reach

5.3 To Scurry

5.4 To Bend Down

,

5.5 To Stoop

5.6 To Slide

Concluding Comments

Chapter 5: Future-Oriented Verbs

1. Preliminaries

2. Verbs of desire

2.1 To Crave

2.2 To Hanker

74

76

77

79

:

;

80

81

84

84

86

88

90

92

93

94

95

97

99

101

102

102

103

105

106

107

107

108

109

110

Ill

Ill

Ill

112

113

113

114

115

119

120

121

122

Vil

2.3 To Hunger

2.4 To Pine

2.5 To Thirst

2.6 To Hope

2.7 To Long

2.8 To Wish

2.9 To Yearn

3. Verbs of Request

3.1 To Appeal

3.2 To Ask

:.

3.3 To Bargain

3.4 To Beg

4. Verbs of Effort..

4.1 To Strive

4.2 To Struggle

4.3 To Labor

4.4 To Try

5. Verbs of Purpose

5.1 To Fish

5.2 To Hunt

5.3 To Fight

5.4 To Grope

5.5 To Forage

5.6 To Aim

5.7 To Apply

5.8 To Campaign

5.9 To Wait

5.10 To Look

5.11 To Watch

6. Concluding Comments

Chapter 6: Verbs of Speech and Expression

1. Preliminaries

2. To Argue

3. To Plead

4. To Speak

5. To Preach

6. 7o Teach

7. To Cry ;

8. To Yell

9. To Roar

10. To Shout

11. To Mutter

12. To Explain

123

124

125

125

126

126

127

128

128

129

130

130

131

132

133

133

133

134

135

136

137

138

138

139

141

142

145

152

153

154

;

;

„...

156

157

158

158

160

161

161

162

163

164

165

165

vin

13. Concluding Comments

1.

2.

3.

4.

Chapter 7: Towards a Potential Meaning

Preliminary Comments .,

Main-Use Descriptions

2.1 Before

2.2 Representation

2.3 Support

2.4 Purpose

2.5 Of Advantage or Disadvantage

2.6 Of Attributed or Assumed Character

2.7 Cause or Reason

2.8 Of Correspondence or Correlation

2.9 Of Reference

2.10 Of Duration and Extension

Towards a Potential Meaning Hypothesis

3.1 Fur's Potential Meaning

Concluding Comments

Chapter 8: Final Conclusions

1. Preliminary Comments

2. Determining Fur's Potential Meaning

3. Concluding Remarks

Bibliography

167

168

171

175

175

178

180

186

187

188

193

194

196

197

203

203

205

206

208

210

General Introduction

1. The Problem

For, a high-frequency word in English can function as a preposition, a

conjunction, or as a complementizer {cf Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman 1999: 639)

and has been attributed as many as 31 distinct lexical senses. Thus, it comes as no

surprise that for, like other frequently occurring prepositions, is especially difficult to

teach to learners of English as a second language. The present study was undertaken in

an attempt to determine whether there is a core meaning, or potential meaning, that

determines the use of for in discourse. A clearer view of this meaning would allow a

clearer view of the influence of contextual factors on the resulting message of

utterances containing this preposition and help to organize the various senses in a

more coherent and comprehensible manner.

Determining a core or potential meaning begins by observing and analyzing

language in context such as provided by a corpus of actual language use. A survey of the

literature reveals that linguistic observation and analysis based on corpus analysis or

authentic data is by no means relatively recent. The Alexandrians in the third and

second centuries B.C. searched for recurrent parallels in texts and the Stoics cited

examples from texts to demonstrate differences in grammatical structures. As well, the

great nineteenth century Danish grammarian, Otto Jespersen, and the American

structuralist, CC. Fries, used authentic data, be it in the form of literary sources

(Jespersen) or letters written to a government agency and recorded telephone

conversations (Fries). Unfortunately, with the advent of transformational grammar,

using a corpus or actual texts from written or oral discourse was largely abandoned

because, according to Liles (1971: 7), "the transformationalist is more concerned with

the system that underlies the language than he is with the actual speech of an

individual...." Consequently, this approach focuses on "competence," which belongs to

the fictitious ideal speaker rather than on performance, or actual use of language by a

real speaker to produce discourse. If "competence" is taken in the realistic sense of a

real speaker's subconscious knowledge of language however, one can argue that it can

be accessed through a speaker's performance as attested by a corpus containing

authentic data.

It is this interpretation of the competence/performance dichotomy

which is adopted here. With respect to prepositions, this usage-based approach has

been taken by Lindner (1982) on up and out, Brugman (1983) on over and Todaka

(1996) on between and among.

In these studies, authentic texts, such as found in a

corpus, provided the data on which these authors based their observations and drew

their conclusions.

In any case, according to Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman (1999: 411) there is

no known study "that has focussed on the meaning (s) of for in authentic texts." While

the study of words and grammatical structures in English has been progressing for

many years, there has only recently been a return to sound scientific methodology

involving authentic texts, due in large part to computers and their capacity to store

large databases of real language examples. Perhaps this explains why there has yet to

be a study on for in authentic texts.

This study is based on the hypothesis that it is possible, even for a word that

appears to be highly polysemous, to determine one meaning that will explain all

observed usage. Clearly it will be necessary to define the semantic content of for and

the extent to which the context and speech situation contribute to the messages

conveyed by utterances containing this preposition. Most grammars describe the

grammatical relationship observed between two sentence components as either spatial

or temporal, treating this relationship as the 'meaning' of the preposition. For these

grammarians a preposition's meaning is derived from the nature of the relation that it

expresses in a given sentence. For instance, Quirk et al. (1985) provide at least 9

categories of prepositional meaning, giving the impression that there is one category

per use. Their account is based on the point of view that prepositions are described

with respect to "relational meaning" such as PLACE, TIME, INSTRUMENT and CAUSE,

though they do acknowledge that "it is difficult to describe prepositional meanings

systematically in terms of such labels" and consequently add that "meanings are

elucidated by paraphrase, by antonymy, or grammatical transformation."(p. 320) In

any event, the nature of the meaning expressed by the preposition in the case of for can

be either spatial or temporal, an observation that raises the question as to whether

spatial for is a separate form from temporal for, a homonym, or whether for is indeed

polysemous. However, if for is polysemous, and has different senses in different

contexts, then what explains the use of the same sign to express them? Clearly for must

have meaning on its own before being used in a context or situation because, as Hirtle

(1989:135) states, "if one combines a number of meaningless words to form a context,

the context itself will be meaningless." On the other hand, if the 31 different senses

expressed by for are all homonyms, how is the listener to know which of the 31

homonyms is appropriate in a given context? In other words, if there is no indication on

the level of sign as to what meaning is being expressed, how is the speaker to know

whether, in the case of for, a spatial or a temporal relation is being expressed? This

then is the problem according to Hirtle (1997: 69):

how to account for a difference of meaning when there is no difference in the

visible or audible signs expressing those meanings, when in fact the principle

of differentiation must lie, not in what differentiates two contexts, nor in what

differentiates two words, but in what, within a single word, differentiates two

of its meanings.

In other words, the problem is to define a semantic content that can explain the

message conveyed by an utterance containing for in its numerous and various uses

beyond the specific nature of the relation being expressed in each individual sentence.

Naturally, the teaching of multiple senses of a preposition to second language

learners is difficult, with the not surprising result that the latter misuse or avoid using

this preposition. This can be observed in the examples below taken from usage of

advanced students of English as a second language:

*... he had us deliver the piano on Friday, he promised to pay pizza, (instead of to pay

for the pizza)

* Without her job, she would not be able to pay her studies, (instead of to pay for her

studies)

* Mom, you don't have to search a painter anymore, I found someone, (instead of to

search for a painter)

*...will be eligible to the draw, (instead of eligible for the draw)

* When she was young she rode her bike to school for the time of her elementary and

high school studies (instead of during the time)

l

If grammar books are to be of greater service to the learner and teacher, then

prepositional meaning must reflect a lexical content that can help one to understand

and explain all observed usage rather than simply enumerating uses and treating the

messages observed in each use as if they were different meanings of the same

preposition. The aim of this study is to formulate an explanation regarding the

meaning of for through the analysis of an extensive corpus, giving careful consideration

to the explanations and descriptions found in grammars and dictionaries. The results of

this study will determine whether one of/or's actual meanings as observed in discourse

is more central, or more prototypical, and the other meanings somehow derive from it,

as purported by Prototype Theory, or if in fact a potential meaning, albeit abstract, can

be described with enough lexical content to avoid the label 'delexicalized'.

2. Objectives

This research will be the first study to examine actual language use for the

purpose of determining the basic meaning of for. Based on the analysis of over 5,000

attested examples from written and spoken English obtained from sources such as the

Brown University Corpus, the British National Corpus, the Corpus of Contemporary

American English, the aim of this study will be to address the following specific issues:

1. To systematically observe and analyse/or in modern-day usage.

2. To determine and formulate a core meaning, or potential meaning, that explains all

the observed uses offor in discourse.

3. To situate the potential meaning within a theoretical framework.

4. To identify the lexical content of for.

5. To understand through the meaning of for why it combines with certain words and

not others.

6. To understand through the meaning of for its many different functions in a

sentence.

3. Corpus Methodology

3.1 Preliminary Remarks

This study of for utilizes a typical scientific methodology involving three phases:

observation, reflection and analysis. These phases are based on an inductive approach

in which generalized conclusions leading to a potential meaning hypothesis are formed

based on a finite collection of specific observations of authentic examples. It is a

corpus-based approach in which actual language is studied in naturally occurring texts.

While the goal of this thesis is to determine a central underlying meaning, or potential

meaning, the actual observation of for in numerous corpora also aims to uncover

typical patterns of language use and analyze the contextual factors influencing

variability. This approach is much in keeping with Biber et al (1998: 3) who describes

the central research goals of corpus study as "assessing the extent to which a pattern is

found and analyzing the contextual factors that influence variability." The quantitative

measurement will involve the collocations of for and how frequent each of these

collocations is. On the other hand, the grammatical associations will reveal how for

functions in a sentence and how systematic patterns arise from these associations.

Thus, it is hoped that through the analysis of lexical and grammatical associations

insights can be gained into a core or potential meaning of for. Obviously,

comprehensive studies of usage, "cannot rely on intuition, anecdotal evidence, or small

samples; they rather require empirical analysis of large databases of authentic texts, as

in the corpus-based approach." (Biber et al 1998: 9)

3.2 The Corpus

The corpus on which this study is based is composed of more than 5000 attested

examples found in the following sources:

1.

2.

3.

4.

The Brown University Corpus

The British National Corpus

The Collins Cobuild Bank of English

The Corpus of Contemporary American English (Brigham Young

University)

5. The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Edition

6. Grammars, articles and books listed in the bibliography

7. Examples collected personally

Actual citations in the thesis number 515, most of which are representative examples

of the sense being analyzed. By selecting representative examples it was not necessary

to cite all 5,000 examples, which would have swelled the size of the thesis excessively.

3.3 Method of Analysis

The corpus analysis involved analyzing the various examples by first of all

grouping them into already known relationships. An important part of this involved

grouping the corpus examples according to the collocations found with for. A further

dimension of this problem is whether a common semantic element can be ascertained

in the lexemes collocating with for, which determines their occurrence with for. Collins

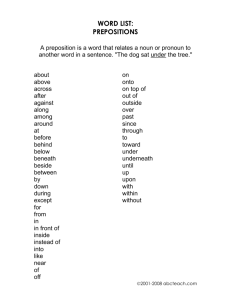

Cobuild (1990:164) provides an example of some of these words:

account for

ask for

care for

go for

make for

settle for

allow for

bargain for

come for

head for

plan for

watch for

answer for

call for

fall for

live for

provide for

Swan (1995: 445-449) lists other common combinations of for with nouns, verbs or

adjectives as:

anxious for

look for

reason for

search for

congratulate/congratulations for

pay for

responsible/responsibility for

sorry for

Analyzing the corpus with respect to the above collocations has led to further insights

about for. Consideration will also be given to examples that do not fit into any of the

above categories. In addition, the frequency of occurrences, when pertinent, will be

noted as a way to determine the most common usage.

Then, a more fine-grained analysis of the meanings of for as described by a

selection of grammars and dictionaries, especially the OED and Webster's, was

undertaken with a view to applying the observations and preliminary conclusions to

these descriptors' proposals of for"s meaning. The OED's descriptions of meanings are

based on thousands of actual attestations from a wide variety of printed sources. Thus,

the corpus analysis of for has directly or indirectly involved thousands of authentic

uses of for. This corresponds to a scientific approach using the method of induction,

going from observing particular uses with specific individual examples to the general

8

level, at which a hypothesis is formulated to explain all of the particular facts found in

the data.

3.4 Order of Presentation

The first chapter describes the theoretical approach taken in which the word is

considered as the basic unit of language, with each word being seen as having its own

semantic content, or mental representation, independent of and prior to its utterance

in any particular sentence. As well, other theoretical approaches with respect to

prepositional meaning are considered, in particular approaches that consider

prepositions as having a purely syntactic function with little lexical content.

In the second chapter, for is considered from a diachronic point of view. On the

semantic side of the problem, the question of to what extent the lexical content of for

has been reduced through the process of generalization to make for a highly

polysemous word is investigated. In this chapter, the development of for from a limited

use, possibly involving one single sense, into its multiple senses, is observed, and the

question is raised as to whether or not this first sense can contribute to a more unified

explanation of modern-day usage of for.

In the third chapter, the proposal that for has a 'complementizer' function is

evaluated, as well as questioning certain claims found in the literature, such as whether

for-to complements are limited to emotive complements, when for functions as a

complement or as a preposition, and if the some of meanings proposed for for by some

authors, in particular Bresnan (1979) and Lindstromberg (1996), can explain this

particular use of the preposition. What does emerge in this chapter, with the

examination offor in phrases composed of for + NP + to-infinitive, is an impression of a

meaning-content implying both motivation and directionality. This first impression

became a cornerstone with respect to formulating a hypothesis regarding for's

potential meaning as that of a movement

Chapters 4 to 6 involve the actual analysis of the examples selected from the

various corpora. In particular, Chapter 4 is dedicated to verbs signifying movement

that co-occur with for and where applicable when for can be opposed to the closely

linked preposition to. Chapter 5 is dedicated to verbs implying a future orientation for

the realization of their lexical content. Chapter 6 is dedicated to verbs of speech and

expression. As a result of observing hundreds of examples in these chapters, a clearer

image of for's potential meaning begins to emerge, especially the observation that the

largest number of uses relates to purposes, motives and intentions. This led to some

preliminary conclusions about for's potential meaning as bringing to the message an

impression of a forward movement leading to a (desired) result, or a resultant

situation, with the movement representing a means to achieve the desired end.

Chapter 7 presents a preliminary postulate regarding for's potential meaning, as

a forward movement leading to a result. This first preliminary postulate is then

applied to the main uses of for with a view to further refinement of the postulate

regarding for's potential meaning. Once a final postulate was determined, one that can

be applied to all the main senses offor as determined by the OED, a schematic diagram

of this meaning is then presented. Then, as within a fully scientific method, the next

step was to test the hypothesis by applying it to specific uses.

Chapter 8 presents final conclusions by summarizing how for's potential

meaning was determined through observation, reflection and analysis. In addition,

some consideration is given to areas that require further research.

Chapter 1

The Theoretical Framework

1. Introduction

The use of a corpus assumes that linguistics is a science of observation based on

the scientific method, a method that involves observation and reflection. This study is

based in addition on Gustave Guillaume's general theory of language, also known as the

Psychomechanics of Language, a theory that considers the activities of observation and

reflection to be intimately linked. However, it is important to note that while a corpus

can provide an object of study, it is not the only reality of language. Discourse as

reflected in a corpus, is in fact a product created by language users and for this reason

it must be analyzed taking into account the mental processes involved in the

production of this product. Therefore, the study of language, involving observation and

reflection, must be considered with respect to two facets of language, one being

discourse (the corpus), which is what Guillaume considers the "physically visible" and

the other, tongue, at the subconscious level, which he refers to as the "mentally visible".

11

Thus it can be argued, as explained below, access to "tongue" is obtained only through

reflection on what is visible in "discourse".

Guillaume never mentioned the importance of observation in

linguistics without stressing that it must be accompanied by

reflection. Convinced as he was that, on the mental side, the

reality of language is largely subconscious and so extends far

beyond what direct observation can reveal, he realized that this

hidden part can be reached only by analysis, by reflecting on

observed data. He often spoke of observation and reflection in

terms of their results —seeing and understanding—or in terms of

their objects—the perceivable and the conceivable. And he

frequently pointed out that the linguist must commute between

the perceivable and the conceivable in his effort to understand

what he sees and to see what he understands.

(Hirtle, 1984: XII)

Consequently, observation of the corpus, the "perceivable" is intimately linked to

reflection on the "conceivable", for it is in the realm of the subconscious that resides the

ultimate reality of language-tongue, a reality that does not belong to the realm of the

observable but is nonetheless real, and which constitutes the principal causal factor

lying behind discourse.

Scientific reflection on the conceivable cannot be a mere flight of fancy,

however: a theory is required to provide the framework or guide in which this

reflection can take place, for without it a coherent explanation linking all observed uses

would in all likelihood be impossible. Yngve (1986: 2) makes much the same point

when he argues "...for observations unconnected to adequate integrating and

interrelating theory are little more than a mass of unorganized facts, and thus only a

feeble contribution to linguistic knowledge." Moreover, observation of a corpus can

reveal usage and patterns of usage not explained by grammars or instances that

contradict current explanations. Thus an attempt must be made to reflect on these

occurrences in order to explain their use. However, any attempt to explain these

observations outside of a linguistic theory would mean adding another explanation of

usage to what is already written and therefore continuing to support the 'separatemeaning-for-each-use' model. This would not advance our understanding of this

12

preposition but would only contribute to the impression that for is highly polysemous

and impossible to understand.

2. The Theoretical Approach

Gustave Guillaume considered the word to be the basic unit of language and

each word to constitute the means by which a speaker can voice, through discourse or

inner dialogue, his experience. Hirtle (1993: 50) writes that "the meaning expressed by

a sentence, or set of sentences constituting a discourse, is a linguistic reconstitution of

an experience which itself is unsayable" and that "this meaning can be expressed only if

it has first been represented by words." In other words, Guillaume postulates that

words are the means of representing experience through language and that a word is a

unit made up of a physical sign and a mental significate. Furthermore, this 'mental

significate' or meaning, according to Hirtle (1997:112) consists of both a lexical matter

proper to that particular word and a grammatical form. Lowe (1996a: 83) describes the

word structure of English in the following way:

In English ... the lexical matter of a word is individuated in

tongue, established in the subconscious as a particular lexeme

distinct from every other lexeme in the language. As such, a

lexeme in English is particularizing and tends to be expressed

byasingle phonological sign.... The grammatical form of a word,

on the other hand, is generalizing in the sense that it categorizes;

that is, it situates the particular lexeme in one of a limited set of

broad categories, the parts of speech.

This implies that the choice of a word is meaning-motivated or experiencemotivated, which in turn suggests that the syntax of a sentence is not autonomous of

meaning but instead is influenced by both the lexical and grammatical meanings

expressed within each of the words of which it is made up. Indeed, Hirtle (1998: 97)

implies a certain coherence between the words when he states that syntax results from

"preconscious mental operations of relating one meaning component to another."

13

Thus it is argued that each word has its own make-up, or mental representation,

independent of and prior to its utterance in any particular sentence and is not

dependent upon the context evoked by the sentence for its meaning, but instead

contributes meaning to the sentence. Meaning it should be pointed out, does not refer

directly to reality, but instead to the speaker's experience of reality, since the external

world has to first be mentally experienced by the speaker before it can be represented

mentally and talked about.

In this way, every lexical element involves a representation corresponding to its

semantic content, referred to as its meaning, or significate1, which in turn is linked to

its corresponding phonological form, referred to as its sign2. However, representing

the world of experience corresponds to only one side of the language coin, the other

side being expression. In other words, language is the tool, through words, by which we

represent and express our conception of reality or our world of experience. Yet,

representing and expressing our experience would not be possible without an act of

language, a dynamic process called on any time we have something to say about

something. This process, or operation, involves two facets of language, namely tongue,

which can be described as a set of mental programs that a speaker has available in his

subconscious and the other, discourse, which is actual language consisting of words and

sentences. In other words, according to Lowe (1996a: 78), within the theory of

Psychomechanics, an act of language:

occurs whenever a speaker calls on the resource of tongue to

represent, to make sayable, some portion of his experience and

then goes on to say, to express, what he has represented, producing

thereby a bit of discourse, a sentence. When a person speaks, when

he performs an act of language, he carries out an operation of actualization

between tongue and discourse, of realization between potential and

actual, of transition between permanent and momentary, (italics added)

1

2

Other corresponding terms for significate are sememe and alloseme.

Also known as morpheme and allopmorph.

14

Tongue, therefore, provides the means for representation or rather gives the speaker

the instrument needed to represent his experiences for "without representation, no

expression would be possible" (Lowe, 1996a: 78). Discourse, on the other hand,

represents the actualization, or result, of the act of language.

Language thus has two modes of existence, tongue and discourse, involving two

distinct types of operation, namely representation and expression permitting the

passing from one to the other, and two types of meaning. First, a potential meaning or

significate in tongue, which is a generalized representation of experience, or "a

collector or condenser of impressions" (Lowe, 1996a: 80) and, secondly, actual

meaning as observed in a sentence. This meaning is one actualization of the potential

meaning in tongue and can be described as an expression of a particular experience, or

"a conveyer of impressions" (Lowe, 1996a: 80). In other words, the actual meaning

observed in discourse is a reduction of the potential meaning, which is unobservable in

tongue, to one of its possible meanings, which is appropriate to the specific situation

being expressed.

Language, then, is essentially a dynamic process consisting of a series of

operations between tongue and discourse, or "an acquired mental program for

actualizing the appropriate words to represent the intended message and combining

them into sentences to express it" (Hirtle, 1994: 113).

Thus a maxim of

Psychomechanics is that at the root of language we find tongue, a system of systems,

with the system of the word at its basis. The word-forming mechanism which

constitutes the system of the word not only. involves a "regular means whereby

experience may be transmuted into a linguistic representation linked to a sign" (Lowe

1996a: 80), but also the means by which a word's significate incorporates two types of

meaning, namely lexical and grammatical. From the point of view of a representational

mechanism, according to Hirtle (1993: 52), "this means there must be an operation of

ideogenesis to provide the lexical component and an operation of morphogenesis to

provide the grammatical component." It is in this way that the lexical significate

determines the notional content of a word while the grammatical significate

15

determines the formal content of a word, such as number, gender, tense, mood, and

more importantly especially with respect to prepositions, the syntactic function of a

word. In a language such as English where, unlike in Eskimo (Lowe, 1996a: 81), word

order is quite strict, prepositions are used to indicate the relations between words in

place of grammatical suffixes such as those found in Eskimo. Thus it follows that the .

system or operation of word-forming must be closely linked to the system or operation

of sentence-forming. In other words, syntax is not based on arbitrary rules, but rather

on the grammatical and lexical meanings of a word; consequently, according to Hirtle

(1995:83):

A meaning-based approach seeks to describe how any word is

constructed in thought, meaningwise, in such a way as to permit

it to be used in a sentence, to permit it to enter into the syntactic

relation the speaker wished to establish for it. That is to say, a

meaningful approach to language leads to a theory based on the

word because in any language the first form for expressing meaning

is the word and so the nature of a syntactic relationship is seen to

be conditioned by the nature of the words involved.

This, then, presents a view of the word not as a form to be studied solely from

the point of view of how it functions in a sentence, or solely with regard to the lexical

notion attributed to the word, but instead with a view to discerning how the two, the

grammatical function and the lexical notion, both contribute to the meaning expressed

by a sentence. The purpose of this study is to attempt to determine a potential

meaning to be derived not only from the grammatical component, or relational

function of the preposition in the sentence, but also from the lexical component. To be

understood and properly taught, prepositions must be defined with respect to their

lexical notion and not just with respect to their grammatical role or function.

According to Guillaume (1984: 119), "a word with a material meaning, a word which is

a lexeme, contains indications as to both its fundamental meaning and its intended use

- the role, defined within certain limits, it is slated to play in the sentence."

16

In addition to the semantic content of the words of which it is composed, the

message conveyed by any utterance is also a product of the context and co-text in

which the utterance occurs. The speaker treats the hearer as an intelligent coparticipant in the communicative act, expecting him to infer the total message not only

from what is expressed by the words uttered, but also by putting what is said into

relation with general knowledge of the world and particular knowledge of the speech

situation and what has been said so far in the conversational exchange. It is extremely

important to distinguish between meaning and message. One of the main goals of our

research is to show how one linguistically-signified meaning can give rise to a

multitude of different messages according to what other sorts of meaning it is

combined with and the different types of context in which it is used.

3. Other Approaches

The study of prepositions can be done from two points of view, grammatical and

lexical, the former focusing on the function or role of the preposition in the sentence

and the latter concentrating on what if any meaning a preposition contributes to an

expression. Indeed, there does seem to be agreement among linguists (cf Hirtle, Bates,

Schulze, Langendoen) that prepositions "carry little meaning" or are "highly

dematerialized."

This has led Bates (1976: 353) to state that it is "tempting to

distinguish a great number of distinct uses for each preposition; in this way most

prepositions appear to be polysemous." This comment is based on the view that

prepositional meaning is nothing more than a description of the senses expressed in

various sentences; in this way lexical content is ignored, if in fact, there is any lexical

content postulated at all. In other respects, grammarians diverge as to whether or not

prepositions are "words", "structure words" (Kolln, 1982: 113), "grammatical words"

(Lowe, 1996a: 81), "morphemes" (Rosenbaum, 1967: 24) "particles" (Schulze, 1987: 4),

"meaningless formatives inserted for purely grammatical purposes" (Chomsky in

Langacker, 1992: 296) "as an annoying little surface peculiarity" (Asher & Simpson:

17

1994: 3303) or simply as "appendages to nouns or pronouns" (Asher & Simpson: 1994:

3303). Prepositions are often analyzed in conjunction with the noun phrase that the

preposition governs, i.e. as "prepositional phrases." In some cases, prepositions are not

defined on their own as separate words with a distinct lexical meaning but rather by

their syntactic function, as in Jackson (1980: 69):

In these cases the preposition has a purely syntactic function

in relating a verb, adjective or noun to a following object or

complement. It is more or less meaningless, since it cannot be

replaced by any other preposition and thus enter into a

meaningful contrast

Another case in which for is generally treated as meaningless is when it is used

to introduce the subject of an infinitive. The term "complementizer" was first applied to

this use by Rosenbaum (1967), who claims that for functions as a 'marker' with respect

to predicate complements and "co-occurs only with the complementizer to" (p. 24).

This analysis makes for a mere sign, not a word with a distinct lexical or grammatical

interpretation. Similar analyses of for + noun + to-infinitive are proposed by Seppânen

(1981), Mair (1987) and Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman (1999), all of whom focus on

the function of the/or-phrase in the sentence.

Unlike these authors, who consider the complementizer function of for from a

syntactic point of view, Kiparsky & Kiparsky (1970) analyze this function according to

the semantics of the matrix verb: according to them the for-to complements "occur with

a semantically natural class of predicates...which we term EMOTIVITY... to which the

speaker expresses a subjective, emotional, or evaluative reaction." (p. 169). Menzel

(1975:78) clarifies Kiparsky & Kiparsky's position by stating, "embedded sentences

with the surface form for NP to VP are embedded under matrix verbs with the features

[+ EMOT] and [-FACT] ...because FOR-TO complements cannot take the head noun

fact..." In other words, with respect to 'fact' "the speaker presupposes that the

embedded clause expresses a true proposition" (Kiparsky & Kiparsky, 1970: 147).

Unfortunately, these authors give 'factive and emotive examples' such as, important,

18

crazy, odd, in addition to 'non-factive and emotive examples' like improbable, unlikely, a

pipedream suggesting that the complement can be either [+FACT] or [-FACT] in

addition to [+ EMOT]. If, as Menzel (1975) suggests, the features of the matrix verb,

namely [+ EMOT] and [-FACT] determines the type of complement, then the question is

how can the above predicates like important, crazy with the feature [+FACT] etc., occur

with for-to complements? While it is not the purpose of this dissertation to explain this

contradiction, (cf Mair, 1987), it does point to the complexity of analyzing for

independently of its own semantics and only from the point of view of the semantics of

the matrix verb or the semantics of the predicate.

Carroll (1983: 424) in her study of Ottawa Valley English (OVE) argues that "for

shows up as a preposition in front of to-infinitives but is a complementizer when it

shows up before NP subjects." This implies that/or sometimes has meaning (expressing

the notion of purpose, for instance, in / am here for to fish) and sometimes not (We

waited for somebody to repair the car). Such a position is obviously problematic: how

can a meaningful element suddenly lose its meaning in certain contexts? This study

will take a close look at for in its use to introduce the so-called subject of an infinitive in

order to discern what is going on in this case.

Relevant to this problem is Duffley's (1992) work on the English infinitive and

further research on the semantic role of the preposition to. He (2000: 232) uses the

following examples to point out that the nuance between the direct-object construction

and that with a prepositional phrase can sometimes be extremely slight:

a. He craved pardon

b. He craved for pardon.

Furthermore, he points out that the prepositional phrase in (b) has a semantic parallel

with infinitive constructions as in He craved to be pardoned. This same view is reflected

in Seppanen (1981: 388) who claims "the three forms of postmodifier, for NP, to V, and

for NP to V... seem to be semantically equivalent." A logical conclusion might be that

19

the /or-phrase shares some of the semantic content of the to-infinitive complement.

This hypothesis will be further investigated in the present study.

The various approaches taken with respect to for underscore the need for an

explanation that can take into account the various functions of for, why for occurs with

certain verbs and adjectives, to what extent the matrix verb governs the use of for, why

for is the preposition used to introduce the "subject of the infinitive" in a/or + noun + to

+ infinitive construction and under what circumstances for is a direct or indirect object

In order to be complete, this explanation must consider not just the grammatical

function but also the lexical content of for and how this contributes to the various roles

and functions offor.

4. D efining Prepositional Meaning

•

■

While the role of prepositions in sentences has been observed in considerable

detail, what is not so well understood is how the lexical content conditions this

functional role. Indeed Curme's (1947: 19) definition of a preposition as "a word that

connects a noun or pronoun with a verb, adjective, or another noun or pronoun by

indicating a relationship between the things for which they stand" continues to be the

standard one. Hewson & Bubenik (2006: 39), based on Guillaume (1982: 130-132),

describe prepositions as "non-predicative" parts of speech, and distinguish them from

"predicative" parts of speech, i.e. nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs: the former are

grammatical and function within the "internal system of language" while the latter are

lexical and represent "perceived categories ... of the experiential world." Other studies

give the impression that prepositions bring no meaning at all to the sentence. Thus, for

the most part grammar books neglect any description of meaning with respect to

prepositions, mostly providing explanations that correspond to the syntactical

properties of this category. This has led Schulze (1987: 3), Quirk et al. (1985), Jackson

(1980: 69), among others, to suggest that the syntactic environment determines the

semantics of prepositions. This implies that prepositional meaning is merely relational,

20

functional and grammatical, determined not by the preposition itself but by the

surrounding verb or noun phrases, and leads to the description of prepositional

meaning as denoting temporality, spatiality, topic, purpose, similarity, instrument,

accompaniment and so forth.

That prepositions are considered relational, or functional words fulfilling a

purely syntactic function is not surprising considering the fact that some prepositions

have taken over the role of inflections indicating grammatical case. Historically, case

forms that once expressed the relationship of one word to another, denoting notions

such as location, possession or instrument, have now been replaced by the prepositions

such as at, of and with. This view has influenced some grammarians, among them

Jackson (1980: 88), who considers prepositions as relational words that "sometimes ...

mean some specific relation, such as 'place at which', 'direction', 'time when', 'cause'."

Similarly, for Fries (1940) the meaning of a preposition is determined by the inflection

it replaces; moreover, because meaning and function are the same with respect to

prepositions, these words are claimed to have little or no meaning. Yet, the fact that

not all prepositions originate from the disappearance of inflections - for example for raises the question of how such prepositions can evoke a meaningful relationship

without having at least a minimal meaning. Perhaps what needs to be considered is

whether it is the syntactic environment that determines a preposition's meaning, or if it

is not rather the preposition's meaning that determines the syntactic environment.

4.1 A Cognitive Approach to Lexical Analysis

Recent attempts have been undertaken within the theoretical framework of

cognitive linguistics to explain prepositions in terms of a lexical analysis. Claudia

Brugman's work on the preposition over presents a point of view in which she

proposes that the relationship expressed in the sentence is directly related to

experiences in the world, which give rise to the preposition's meaning, as she explains

in the following passage (1983: 3):

21

I will be demonstrating that imaginai representations of the spatial

relationships studied are necessary for explaining the various senses

of the word. The "representational" depictions in the paper are not

identical with the mental representations, the nature of which I can

make no claims about. However, since the depictions exploit familiar

spatial configurations existing in our experience of the world and I

believe our understanding of such configurations to be grounded in

those experiences, / do believe that the depictions bear some resemblance

to the corresponding mental representations... (italics added)

In other words, according to Brugman, her concrete depictions on paper of spatial

relationships with respect to over resemble, though are not identical with the mental

representation or meaning of the preposition. Yet to what degree her "depictions" are

the meaning of the preposition is not defined, as only a certain degree of resemblance is

claimed: "the depictions bear some resemblance to the corresponding mental

representation."(my italics) Ungerer and Schmid (1996: 161) reflect Brugman's work

on over by describing "mental representations" as "cognitive patterns" as indicated in

the following passage:

...locative relations like—OVER—and—UNDER... are regarded as IMAGE

SCHEMAS, i.e. simple and basic cognitive structures which are derived

from our everyday interaction with the world. The idea is that by experiencing

for example many instances of things-over-things we have acquired some

sort of cognitive pattern or schema of the OVER-relationship which we can

apply to other instances of the locative relation.

Through these "cognitive patterns or schémas" or "representational depictions" these

authors present a static set of components or patterns that arise from our everyday

interaction with the world and that to a certain extent are the mental representations,

or meanings, of the preposition.

Sandra and Rice (1995) raise the question as to whether the network analysis of

prepositional meaning mirrors the linguist's mind or the language user's. Clearly,

Brugman's representational depiction of "things-over-things" for the preposition over

does not respect British usage in 77?e post office is over the road from the grocer's, which

22

Hall (1986: 27) describes as meaning "on the other side of. American usage would call

for the preposition across in this example. Is this then a case of prepositional meaning

mirroring the linguist's mind rather than consideration for all usage? Or, again,

according to Sandra and Rice (1995: 92), could it be more the case that "different

linguists are likely to make different distinctions between usage types and to propose

different networks for the same preposition" because there is "a lack of explicit criteria

for distinguishing between usages." Perhaps the problem is not just "a lack of explicit

criteria" but as Hirtle (1994: 111) points out "it would be an error to reduce language

to merely signaling the experience of the speaker, to mirroring the intended message."

Certainly there is a connection between the world of experience and the meaning of a

preposition in a sentence. After all language is a necessary tool for expressing our

thoughts or experiences arising from our interactions with the external world. And

with locative prepositions it seems to make sense to describe their meaning with

respect to our actual experiences in the real world and then to apply these meanings to

more abstract utterances. In this way, / am over him, meaning that one is no longer

emotionally attached to someone, can be explained as a metaphorical application of the

spatial over as in The plane is flying over the city. However, while locative or spatial

prepositions can be mostly understood with respect to actual experience, does this

indicate that prepositional meaning is external to the mind? Korrel (1991: 12), within

the Guillaumian tradition, maintains that "we cannot put our experience into language

if in our preconscious we have not formed generalized images organized in systems

which are there at our disposal whenever we wish to think or say something." While it

can be argued that Korrel's "generalized images" reflect Brugman's "representational

depictions", what is not clear from Brugman's work is how the "representational

depictions" are part of an overall preconscious system nor what it is that allows for our

experience to be organized as depictions or patterns.

Wege (1991: 277) points out with respect to these authors that for them the

semantic structure of prepositions is stored in terms of diagrams and not in terms of

features. In fact, Wege (1991: 282) describes a lexical model for prepositions as

including three kinds of features, namely "an inherent one concerning the arrangement

23

between two entities, a relational one corresponding to a conceptual schema, and a

third one concerning the original semantic domain." Wege (1991: 278) describes

'inherent features' or attributes as an arrangement of two referents. With respect to the

preposition over, the inherent feature is the arrangement of two referents on an

imaginary vertical axis. The 'relational feature' or attribute corresponds to a different

conceptual level, which she indicates can be either a conceptual schema of rest or

motion, or of PLACE and PATH. With respect to 'semantic domain', she states: "it may

be assumed for all prepositions that the semantic domain in which they occur

originally constitutes one component of their lexical meaning" (p. 282). Furthermore a

use of a local preposition in non-local contexts is according to Wege, a metaphorical

extension of its original meaning. She seems to suggest that the semantic domain of a

preposition can be dependent on other "lexical entities" which would indicate that

prepositional meaning is variable and that prepositions are polysemous. In fact, with

regard to polysemy, Wege (1991: 284) writes that "a core meaning underlying all

meanings of a polysemous lexeme is far too abstract in character to be stored

permanently." In our view, the necessarily decontextualized nature of meaning as

stored outside of particular uses is conducive rather than inhibitory with respect to

abstraction.

This raises another question: can the analysis of locative, or spatial prepositions

in determining their lexical content as described above be applied to prepositions that

express a temporal relationship?

With respect to temporal uses of English

prepositions, according to Bennett (1975: 95) "there are a number of respects in which

the temporal analysis will not parallel the spatial analysis." He argues that "this

asymmetry is the result of two well-known properties of time, its unidimensionality

and its unidirectionality" (p. 95) versus the three-dimensionality of space.

Furthermore, unlike Brugman, Bennett (1975: 4) puts emphasis on "intra-linguistic

semantic relationships, rather than on the relationship between linguistic items and

the world in which we live." This brings us back to the basic question: is the semantic

value of a preposition to be found only in the observed relationship expressed in

discourse, or only in the "relationship between linguistic items and the world in which

24

we live," or in a pre-instituted, unconscious meaning, derived from our experience of

the world and actualized in discourse to represent and express a particular intended

message?

4.2. A Psychomechanical Approach to Prepositions

In a psychomechanical approach, prepositions are seen as words and not as

mere appendages to nouns. Nor are they merely grammatical elements, but words with

both a lexical content, albeit abstract, and a grammatical content. A meaningless word

is linguistically impossible according to this theory of language, as each word

represents something in the experience that the speaker wishes to express or in the

intra-mental realm of the concepts used to refer to one's experience. Each lexical

representation is formed in such a way as to allow it to be placed in a cohesive

relationship with the meanings of other words. Indeed it is the role or function of the

preposition to bring parts of the sentence into a cohesive relationship that would not

exist without a preposition, and through the preposition's material or lexical notion to

characterize the nature of this relationship. Lowe (1996b: 66-67) describes the raison

d'être of the preposition from the Psychomechanical point of view:

Si l'on admet, à l'instar de Guillaume, que la langue est un système

prévisionnel, la préposition, tout comme la conjonction de

subordination, apparaît alors devoir son existence à divers types

d'hiatus syntaxiques (...) susceptibles de se produire, dans la

construction d'une phrase, entre deux mots ou deux groupes de

mots, hiatus que la préposition et la conjonction de subordination

auraient pour effet de combler. Cet hiatus, cet intervalle psychique

ou diastème comme le désigne Guillaume, la préposition le résout

en réalité de deux façons. Elle le résout formellement, d'une part,

en rendant effective la mise en rapport envisagée entre deux termes;

elle le résout matériellement, d'autre part, en précisant, par le contenu

de signification qui lui est propre, la nature du rapport par elle établi

entre les deux termes.

25

In other words, the general syntactic function of prepositions is the same from

one preposition to another, namely that of establishing a relationship, or according to

Psychomechanics allowing one word, or group of words, to be incident to another.

Indeed prepositions owe their existence to the semantic gap1 or interval arising

between sentence elements, when one word (or group of words) cannot come into a

direct relationship with another word because the mechanism of incidence is

inoperative.

Syntax, then, in Psychomechanics, can be explained as the result of operations of

incidence, with each part of speech making possible certain of such operations. The

role of prepositions is to intervene as the need arises within this system, a need that is

ultimately determined by the experience the speaker wishes to express. However,

while the existence of a gap or interval created when the mechanism of incidence

provided by other parts of speech is not operational explains the functional role of

prepositions, what needs to be determined for a full explanation of any given

preposition's actual uses is the semantic role of the preposition in question. Indeed, as

Cervoni (1991: 276) points out, the choice of a preposition is determined by its

semantics:

À l'instant où pour combler un diastème, il est fait appel à une

préposition, le choix qui s'effectue est commandé par une exigence

d'accord sémantique, que le linguiste conçoit comme une "convenance"

entre le sémantisme de la préposition et "l'argumentation" qui s'est

développée dans le "diastème."

A case in point is the pair of French phrases un verre à vin (a wineglass) and un verre de

vin (a glass of wine), in which the difference in interpretation is attributed to the sense

the preposition contributes to the overall message expressed by the phrase.

Guillaume theorizes that through its lexical meaning the preposition conveys a

reference to a limit and that each preposition denotes a position either within or

1

When the relation between two words cannot be made directly there is a "semantic gap", or "intervalle

psychique". This gap is bridged by the preposition.

26

beyond the reference limit. He therefore sees the lexical import of one preposition as

forming a lexical system with that of another preposition, one representing a

movement toward a position prior to a limit, the other away from or beyond the limit.

Using the examples of the French prepositions de and à Guillaume (1997: 47) writes:

...l'import de la préposition est une limite de référence dont la préposition

est l'en-deçà ou l'au-delà: de est l'au-delà d'une limite; à, l'en-deça de la

même limite. Raisonnablement, on met l'aller avant le retour, l'en-deça

avant l'au-delà: fe vais à Paris ;Je viens /Je reviens de Paris.

This could be diagramed as follows:

at—involves no movement, position

of contact with the limit

of— no movement, the possibility

of a movement of withdrawal

from the limit

While this abstract binary system provides a working hypothesis for

systematizing the lexemes of prepositions in tongue, it is not clear whether it is

applicable to all prepositions. Hewson & Bubenik (2006: 48) make an attempt to apply

it to English by dividing the 28 core prepositions identified in Ogden's Basic English

into 14 binary pairs in which:

...the first element may be seen as the movement towards a limit, and the second

as a transcendence or departure from the limit so established, each set forming

a radical binary tensor (see Guillaume 1984: 118-119), contrasting'goal and

source, where T marks the term for reversal of the vectors.

27

In the case of the prepositions at and of, as indicated in the binary tensor model below

(c/ Hewson & Bubenik, 2006: 49), there is an initial movement toward the term T,

followed by an orientation away from T, indicating a contrast between a 'goal' notion

corresponding to at and a 'source' idea corresponding to of.

at

~~~

of

v

T

'

+orientation

'

"P

The sense attributed to at is thus that of a movement of orientation leading up to a

limit, while the sense of of is a movement of orientation away from the limit. The

application of the theory to the data is problematic however, as there is no discernible

idea of movement in the meaning of at observed in There is a hardware store at the

corner of King and Waterloo Streets. Even in He threw a rock at the dog, the idea of

movement comes from the verb throw, and at simply expresses the contact, or possible

contact, of the rock with the dog, thereby representing the dog as a target The notion

of'contact' is also proposed by Wierzbicka (1993: 438) to characterize the meaning of

at in the temporal use of this preposition, regarding which she hypothesizes that the

explanation for the fact that at implies sameness of time lies in the idea of contact with

the point in time denoted by the noun phrase following the preposition.

Moreover, the radical binary tensor cannot be applied indiscriminately as a

universal instrument of linguistic analysis. Some grammatical categories are only made

up of one member - this is the case for the definite article in classical Greek and the

basic demonstrative ce in modern French. In these cases, there is no binarity to which

the tensor can be applied and the meanings of these items must be defined in and for

themselves. It will be argued here that this is the case for the preposition for. Hewson &

Bubenik (2006: 49) place for as the initial half of a binary tensor in which it is opposed

to by as 'goal' vs 'source' within the shared domain of 'path', as shown in the diagram

below:

for

;

—% T

by

——————

+path

w-

28

Thus in / did it for you and it was done by me, Hewson & Bubenik argue that the path of

the action shows you as the goal and me as the source, with T being the end-point of the

movement for for and the starting-point of the movement for by. The problem is that

without a context it is impossible to know whether the use of for in / did it for you

expresses the idea of intended beneficiary or that of substitution ('I did it in place of

you'). In the substitution sense, however, there is no impression of a goal. This is even

clearer in an unambiguous example of the substitution/exchange sense such as /

bought the printer for $200: here it cannot be argued that the preposition/or denotes

a goal in any meaningful sense of the term.

The binary tensor does not fare any better in its application to the second

member of the purported two-stroke system. The notion of 'source' seems totally

inadequate to characterize uses of the preposition by such as those found in / walked

right by the bus stop or She was sitting by the door. This illustrates another important

problem with Hewson & Bubenik's application of the binary tensor to the prepositions

for and by: their diagram is based on just one use each of the two prepositions in

question. If this diagram is intended to depict a system in tongue, it must necessarily be

composed of potential rather than actual meanings and based on the observation of the

full range of meaning expressible by the forms. Potential meanings are the basis for

engendering all of the senses that a given form is capable of expressing in discourse

and as such they do not correspond to any one particular use. More importantly, a

hypothesis as to the nature of a potential meaning must be demonstrated to be capable

of engendering all of the known uses of a form. The depiction of the meanings offor and

by in the binary tensor system proposed by Hewson & Bubenik very clearly fails on this

count. For this reason, it will not be adopted here. Moreover, it will be demonstrated

that the meaning offor cannot be reduced to the notion of 'path leading to goal' even on

the potential level; instead, it involves a more complex idea which we will attempt to

characterize at the end of the thesis.

29

Afinalproblem with the binary tensor approach is that while/or can be opposed

to during in its temporal sense (cf. Gruntman, 2000) and to against in its attitudinal

sense, it is not obvious that there is one single preposition which stands in opposition

to for in its full range of usage. Binary tensors oppose unitary potential meanings of

two items per system in tongue, not particular actual senses of a number of different

items in discourse. The evidence suggests therefore that the most promising approach

to the preposition for is to start by looking at this little word in and for itself by means

of a detailed examination of a corpus of attested examples, and to base one's

hypotheses as to its potential meaning on the observation of a very broad range of uses.

This is the methodological perspective which is adopted in this study.

5. Lexical Monosemy

A monosemantic bias with respect to a word's meaning is not exclusive to the

theory of Psychomechanics. Ruhl (1989: 4) argues:

a researcher's initial efforts are directed toward determining a unitary

meaning for a lexical item, trying to attribute apparent variations in

meaning to other factors. If such efforts fail, then the researcher tries to

discover a means of relating the distinct meanings. If these efforts fail, then

there are several words. This approach initially assumes that lexical form

and meaning are fully congruent, and that claims of polysemy, homonymy,

and idiomaticity must be substantiated by detailed study, not merely

asserted as intuitive insights.

Among the researchers considering for from a monosemic point of view is Bresnan

(1979: 82), who writes "that there is a common meaning to for" which she refers to as

"intentional" or "motivational", terms which are meant to express "at once the

subjectivity and the directionality of for." She argues that for expresses subjective

reason or cause (i.e. the reason for attribution or judgment) as in He considers her a fool

for her generosity, where her generosity is the reason that he considers her a fool. In

addition, according to Bresnan, for also expresses purpose, use or goal. She also posits a

semantic relation tying these notions together (1979: 82):

The concepts of reason and purpose are semantically related,

both implying motivation, and both implying directionality,

30

whether from a source or toward a goal. However, the "direction"

is in a sense reversed:

40) for (x) —► Y X is the reason or subjective cause for Y.

He considers her a fool for her generosity.

41) for (x) <

Y X is the purpose or goal of Y.

This book is for your amusement.

Furthermore, she implies that "the choice of 'direction' may follow from the temporal

relations between X and Y" because in (41) the goal, purpose or use is future with

respect to Y, whereas in (40) the /or-complement may describe something

simultaneous with the main predicate and is non-future with respect to Y. Bresnan's

analysis, while interesting, is a prime example of the confusion between meaning and

message. While it is true in (40) that logically her generosity is the cause of her being

considered a fool, we will see later on this study that the linguistic meaning indicates

that this situation is construed rather as a sort of exchange scenario in which in

exchange for her generosity what she gets is his considering her a fool.

It is also significant that for combines with some verbs and not others. This of

itself could lead to certain generalizations about the meaning of this preposition. For

example, Bresnan (1979: 90) claims "...the class of verbs taking a/or-relativized object

prominently includes many so-called "intentional" verbs - verbs which do not imply

the existence of their objects or whose objects are in some sense unspecified or

indeterminate..." According to Bresnan these verbs include "need, want, search for;

those which disallow it include burn, break, trip over, and in general any verbs which

imply a concrete or physical relationship between subject and object." This view is

similar to that of De Smet (2007: 11) who writes that "many verbs taking for...toinfinitives express anticipation, volition, or goal-oriented activities."

These

observations are significant and need to be taken into consideration from the point of

view of which verbs, nouns and adjectives combine with for.

Bresnan's (1979: 91)

conclusion "that the for complementizer has a distinct semantic function which may

account for many of the peculiarities of its distribution, even in relative clauses" does

31

not however explore the question of what generates this function, the nature of the

lexical content brought to the sentence by the preposition for itself.

Tyler and Evans (2003: 2), writing in a cognitive grammar framework, consider

"senses associated with a single particle [which] constitute a semantic network

organized with respect to a primary sense." This idea of a 'primary sense' or 'protoscene' is described as:

A proto-scene is an idealized mental representation across the

recurring spatial scenes associated with a particular spatial

particle; hence it is an abstraction across many similar spatial scenes.

It combines idealized elements of real-world experience (objects in

the guise of TRs and LMs) and a conceptual relation (a conceptualization

of a particular configuration between the objects), (p. 52)

They consider that "other distinct senses may have become derived from the protoscene." This, at first glance, seems to parallel the notion being put forth in this thesis

with respect to a potential meaning, yet what remains to be determined is whether the

'proto-scene' is a prototypical sense or whether it is a schematic potential. According

to Tyler and Evans (2003: 52), "proto-scenes are instantiated in memory due to their