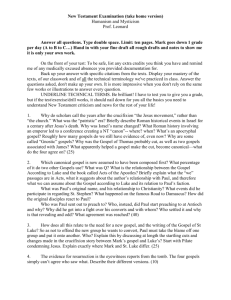

Understanding the Gospels: Genre and Ancient Literature

advertisement

SAN PEDRO COLLEGE – RELIGIOUS STUDIES 2 (intro to the new testament I) INTRODUCTION Matthew, Mark, Luke and John are the first books called ‘Gospels’: what does this mean? Why were they given this description? And what expectations would an ancient reader have of a book with this title? These questions add up to asking about the literary genre to which the Gospels belong. Three reasons demonstrate that this is important. First, what readers expect to find in a book is determined by their initial perception of what kind of book it is. This expectation comes from reading the introduction to the book, seeing the writing style used and examining the literary structure. Thus, a modern reader will have a quite different approach to reading poetry compared to reading a newspaper report of a political event. Similarly, an ancient reader would expect different things from, for example, Thucydides’ historical account of the Peloponnesian war and Aristotle’s handbook for students on rhetoric. Second, knowing something about the genre of a work can help us, reading centuries later, to enter into how the ancient author and ancient readers would experience the book. Genre forms an implicit ‘contract’ between writer and readers, with shared expectations, which enables good communication to take place – expectations which are modified as the readers read and re-read the book. Third, a knowledge of genre means that we can recognize something new is being done. Authors can and do break the bounds of established literary genres and introduce fresh elements or even new genres – and we shall see that some argue the Gospels do precisely this. WHAT DOES ‘GOSPEL’ MEAN? To the first Christians it would be great surprise to find a book called ‘gospel’, since for them ‘gospel’ meant the gospel message. The word itself (Greek evangelion) means ‘good news’ and was used in Graeco-Roman literature for announcements such as the accession of a new emperor. (See page 4 for example.) In Jewish writings, the cognate verb (Greek evangelizomai) is used in announcing the coming of Yahweh to save his people (e.g. Isa 40:9; 52:7; Joel 2:32; Nahum 1:15). Throughout Paul’s letters, which are the oldest books of the NT, the noun ‘gospel’ means the Christian message about the coming, life, death and resurrection of Jesus which Paul and others preach (e.g. Rom 1:1-4,16; 1 Cor 15:1; 2 Cor 2:12), and the verb ‘I proclaim good news’ is used for announcing this message orally (e.g. Rom 1:15; 1 Cor 1:17; 9:16). So how did a word associated with a spoken message become the title of a written book? one gospel (message) of Jesus, but told ‘according to Matthew’, ‘according to Mark’, etc. To answer this question fully, we need to consider two main approaches to the genre of the Gospels: a) the first considers the similarities which the Gospels have with other forms of ancient writings; b) the second focuses on the distinctive features of the Gospels when compared with such works THE GOSPELS AS LIKE OTHER ANCIENT LITERATURE There is a long tradition in scholarship of comparing the Gospels with other ancient writings, and for good reason. Looking for features which the Gospels share with other literature is natural, since if they were totally unlike any other books which were known in antiquity, it might have been harder for them to find acceptance by readers. Like other ancient (and modern) literature, a book would not necessarily have a genre label attached to it (e.g. a modern novel does not usually have the word ‘novel’ on its cover), so a librarian would have to compare the style and contents of Mark with those found in other books. ● THREE KINDS OF ANCIENT LITERATURE Three particular kinds of literature might be considered as potential parallels to the Gospels. a) the ‘acts’ (Greek praxeis) - which were books giving accounts of great historical figures and their deeds. - In the 2nd century AD, Arian wrote his Anabasis about the military campaigns and battles of Alexander the Great, the brilliant Greek general of the 4th century BC who conquered most of the known world. - The Acts of the Apostles is an example of a Christian book using this title - and thus Luke may well be using two different genres of book in his two-volume work, Luke-Acts. - However, the Gospels contain a good deal of teaching by Jesus, and contain relatively little movement and few exploits of the kind which Greek readers would expect in such a book (principally political and military). - Further, Jesus’ trial for sedition and state execution would suggest that he was too doubtful and obscure a figure for treatment in such a book. The first step towards answering this is to recognize that when Matthew, Mark, Luke and John first appeared in writing, they were not labeled as ‘Gospels’. That title was attached to them later, when they were collected together, and each was seen as an expression of the What are the Gospels? – Page 1 of 5 SAN PEDRO COLLEGE – RELIGIOUS STUDIES 2 (intro to the new testament I) b) the ‘memoirs’ (Greek apomnemoneumata) - which were collections of individual stories about, or sayings of, a famous person. - Xenophon wrote his Memoirs about the philosopher Socrates (c. 380 BC) and Plato had also written his Dialogues about Socrates (c. 380 – 350 BC). In about 150 AD Justin Martyr describes an early Christian meeting thus: “And on the day called Sunday there is a meeting in one place of those who live in cities or the country, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read as long as time permits (Apology 67.3).” - Justin also writes “the memoirs of the apostles… are called Gospels” (Apology 66). He thus sees similarities between these Christian writings and the previous ‘memoirs’, although he is unique in describing the Gospels this way. He may choose this term because he writes for pagan readers who would know books called ‘memoirs’. - The Gospels, however, contain much that would be regarded as unnecessary to memoirs, including most of the action within them, as well as the account of the death of Jesus. Indeed, when we remember the percentage of each Gospel which is taken up with the last days of Jesus, his death and resurrection (almost 50% in Mark), and the relatively small amount taken up with Jesus’ teachings, it is likely that an ancient reader would see Justin as stretching considerably the bounds of the term ‘memoirs’ in applying it to the four Gospels. c) the ‘lives’ (Greek “bioi”) of the ancient world - Plutarch was a famous biographer of the first century AD who wrote a number of Parallel Lives which compare and contrast two great figures. He sets out his aims as follows: “I am not a writer of histories but of biographies. My readers therefore must excuse me if I do not record all events or describe in detail, but only briefly touch upon, the noblest and the most famous. For the most conspicuous do not always or of necessity show a man’s virtues or failings, but it often happens that some light occasion, a word or a jest, gives a clearer insight into character, than battles with their slaughter of tens of thousands and the greatest array of armies and sieges of cities. As painters produce a likeness by the representation of the countenance and the expression of the face, in which the character is revealed, without troubling themselves about the other parts of the body, so I must be allowed to look rather into the signs of a man’s character, and by means of these to portray the life of each, leaving to others the description of great events and battles (Alexander 1.1).” - Thus, for Plutarch, and the Graeco-Roman biographical tradition, the ‘lives’ focused on the person, whereas ‘acts’ and other historical writings focused on events. A ‘life’ was written to provide an example or model by highlighting the person’s character or ethos – thus Plutarch says that he chooses the material for his biography in order to draw his readers’ attention to that. - For a long time, it is used to be argued that the Gospels are not biographies, but this argument was usually based on a comparison with modern biographies. It is true that the Gospels lack the full coverage of modern biographies: they say little about Jesus’ childhood and upbringing; they are very uneven in their coverage of his life, focusing particularly on his public ministry of about three years, and especially on the last period; and they do not tell us much about his psychological and personal development. - However, Richard Burridge has mounted a strong argument for considering the Gospels as ancient ‘lives’. He studies a wide range of ancient ‘lives’ and establishes a set of features of this literary genre: 1) opening features: there is usually a title and an opening formula 2) the subject of the biography tends to be the subject of a large proportion of the main verbs in the book, and is given the lion’s share of the space, providing the focus on the subject which Plutarch describes 3) external features including the structure of the book, its style, etc. which enhance the focus on the subject 4) internal features such as the setting, the topics and content included, the values and attitudes espoused or promoted by the work, and the author’s intention and purpose (whether stated explicitly or not). When Burridge compares the four Gospels one by one with this pattern, he finds each of these features to be present in a comparable form in each. This strongly suggests that an ancient reader hearing Mark and the others read aloud (the normal way books were ‘read’ in the ancient world, cf Acts 8:30) would recognize them as ‘lives’ of Jesus. To repeat our earlier point: this does not mean that we should think of them like modern biographies, but it does mean that the evangelists have chosen a vehicle which would be recognizable to a wide readership around the Mediterranean basin. A weakness of Burridge’s conclusion is that ‘lives’ form a very wide category of books, and vary considerably in how much they aim to be true to what happened and how much they write stories which typify the person’s character but which may not have happened. Nevertheless, Burridge has identified a key point which has moved the debate forward and which tells us that the focus of the Gospels is Jesus, the subject of the ‘life’. But much of the last hundred years, the heart of Gospels scholarship has been in examining the communities supposed to be behind the Gospels, rather than their subject. THE GOSPELS AS UNLIKE OTHER ANCIENT LITERATURE The alternative approach in scholarship has been to notice ways in which the Gospels are distinctive and different from other ancient books. A key figure is K. L Schmidt, who published an essay ‘The place of the Gospels in the history of literature’ (1923), in which he claimed that the Gospels should be seen as ‘folk literature’ (as opposed to high literature) because the evangelists did not write in the “I” of an eyewitness narrator and made use of stories and material from others (rather than carrying out the research entirely themselves). Schmidt assumed that the Gospels had been put together by the evangelists collecting stories about Jesus and then putting them together, rather like sticking newspaper cuttings into a scrapbook. This view treats the Gospels as preaching documents, gathering together the stories told in the early Christians’ proclamation about Jesus. The British scholar C. H. Dodd studied the evangelistic speeches in Acts in a very significant work, and argued that there was a fairly consistent pattern found in these speeches. Dodd’s ‘set piece’ study What are the Gospels? – Page 2 of 5 SAN PEDRO COLLEGE – RELIGIOUS STUDIES 2 (intro to the new testament I) was of Acts 10:34-43, Peter’s speech in Cornelius’ home in Caesarea, and he identified six key elements of the speech which formed the pattern of early Christian preaching: a) John the Baptist prepared the way for the coming of Jesus, verse 37; b) these events were promised in the OT Scriptures (the prophets), verse 43; c) Jesus’ ministry was powerful and empowered by God, verses 38-39a; d) Jesus was arrested, tried and executed on a cross, v.39b; e) God raised Jesus from the dead and he was seen by witnesses, verse. 40f; f) those who follow Jesus are commanded to tell others about him, verse. 42 The key step in Dodd’s argument was to notice that these six points correspond to the major sections of Mark, and come in roughly the same sequence: a) John the Baptist appears in fulfillment of the OT (note the quotation form Isaiah 40 in Mk 1:2f), Mk 1:115; b) Jesus’ ministry is outlined and described, Mk 1:16 8:30; c) An extended description of Jesus’ movement to Jerusalem, where he is arrested, tried and dies on the cross, Mk 8:31 – 15:47; d) A brief description of the resurrection of Jesus, Mk 16:6; e) Jesus’ disciples are to go and tell others, Mk 16:7. While Dodd’s picture does not fit completely at every point of detail, it does go a long way to explain why these books came to be called ‘Gospels’, for Dodd shows that they were each an extended narrative form of the gospel message which the early Christians proclaimed. To add to this, R. P. Martin (1972) has examined Mark’s opening verse to see how he ‘titles’ his book. Mark calls his book “The beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the son of God” (Mk 1:1). The word ‘beginning’ (Greek arche) could well have the sense of ‘origin’ or ‘source’ here. If that is so, Mark’s book is an explanation of where the gospel message comes from, what the foundational events which the gospel message proclaims are. On this view the Gospels are the church’s testimony about Jesus rather than biography, for biography’s focus is on the past figure who is remembered, whereas Jesus was not ‘remembered’ by the early Christians – they experienced him as alive and present with them by the Spirit. TRUTH IN BOTH VIEWS? On balance it seems likely that there is truth in both approaches to the genre of the Gospels. It is likely that they would have similarities with other ancient literature, for such familiarity would help readers to engage with the book. Burridge demonstrates by detailed study that there are close resemblances between the four Gospels and ancient ‘lives’, and thereby shows that the focus of these books is Jesus. has done in and through Jesus. Dodd and Martin argue persuasively that the Gospels enshrine the church’s proclamation of Jesus in narrative form - and thus how from a different perspective that these books are all about Jesus. C.F.D. Moule concludes judiciously: Here, then, in the Synoptic Gospels and Acts, each with its own peculiar emphasis, may be found the deposit early Christian explanation: here are the voices of Christians explaining what lead their existence -- how they themselves came to be: telling the story to themselves, that they may tell it to others, or even telling it directly to those others. (Moule 1981,133) WHY WERE THE GOSPELS WRITTEN? So, in order to understand the nature of the Gospels better, we shall ask what we know about the immediate causes of them being written down. On the usual dating of the four Gospels, it is held that Mark is the oldest and that he did not publish his book until the sixties AD. Why did it take so long before writing these books, and what other reasons led to the stories about Jesus taking written form? Broadly four reasons seem probable, within which scholars then debate the precise reasons for each individual Gospel being written. First and most practically, the period of writing the Gospels was a time when the original eyewitnesses were dying. For example, Luke presents himself as part of this ‘second generation’ by separating ‘us’ and ‘those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses’ (Luke1:2). This would give urgency to preserving personal knowledge of Jesus’ ministry for future generations, and a written form would be the most permanent. We might call this an historical reason. Second, there was an evangelistic reason, namely to communicate the gospel message to those who were not yet believers. In the NT letters we get only the briefest summaries of the evangelistic message preached to non-believers (e.g. 1 Thess. 1:9f; 1 Cor. 15:1-7), whereas (as Dodd argued) it seems likely that the written Gospels provide extended narrative summaries of the contents of the Christian proclamation. John seems to say that this is his purpose (John 20:31; contrast 1 John 5:13, clarifying that the letter is for believers) and it may be part of a Luke’s agenda also, depending on whether ‘Theophilus’ is a believer or an inquirer (Luke 1:1-4). Third, there was a didactic (or teaching) reason, to teach those who followed Jesus more about their faith and to help them grow in it. If ‘Theophilus’ was a believer already (Luke 1:3f.) it is likely that this was one of Luke’s aims. Similarly, the five major blocks of teaching material in Matthew (see p. 212 would be wonderfully appropriate explaining Christian lifestyle to a congregation; the sermon on the mount (Matt. 5-7) looks particularly tailored to this end. Fourth, there was a geographical reason, to spread the eyewitness testimony further afield. We know that the early Christians valued the oral passing on the stories about Jesus into the second century (see p. 70), so writing them down did not necessarily supersede the oral traditions. However, it did allow them to spread around more easily, since written documents could be copied relatively cheaply and were light enough for a traveler to carry. But it is also likely that there will be something novel about the Gospels, since they center on what the early Christians believe God What are the Gospels? – Page 3 of 5 SAN PEDRO COLLEGE – RELIGIOUS STUDIES 2 (intro to the new testament I) WHY THESE GOSPELS? Christian tradition from at least the second century AD has identified Matthew, Mark, Luke and John as the accounts of Jesus that are important and authoritative historically (hence ‘canonical’ – in the list or canon of recognized books). However, there were other gospels, many of them written in the century AD. These are so-called ‘apocryphal gospels’ are often attributed to an apostle, e.g. Peter or Thomas. Apocrypha – means “falsely inscribed or falsely attributed” Apocryphal gospels – are falsely inscribed gospel written by an anonymous author who appended the name of an apostle to his work. Most scholars have seen the apocryphal gospels as historically valueless: they contain bizarre stories. One leading scholar speaks of ‘a field of rubble, largely produced by the pious or wild imaginations of certain second-century Christians.’ (Meier 1991, 1:115) ● Infancy Gospel of Thomas - focuses on the birth of Jesus, recounting tales of Jesus as a super-boy ● Gospel of Peter - describes a huge Jesus coming out of the tomb followed by the cross. The notable American Scholar J.D. Crossan has taken a particular interest in this gospel, postulating an early Cross Gospel, on which it was based, from the fifties AD that was used by the canonical Gospels. ● The Gospel of Thomas - was found in a fourth-century Coptic library in1945 at Nag Hammadi in Egypt. It is a collection of 114 sayings of Jesus, many paralleled in the canonical Gospels, but some quite different, e.g. Saying 77: ‘Jesus said… “I am the all; the all came forth from me, and the all attained to me. Cleave a (piece of) wood, I am there” (Schneemelcher 1991, 127); and Saying 114: ‘Simon Peter said to them “Let Mariham (Mary) go out from among us, for women are not worthy of the life.” Jesus said: “Look, I will lead her that I may make her male, in order that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every woman who makes herself male will enter into the kingdom of heaven.” (Schneemelcher 1991, 192) ● The Secret Gospel of Mark - This gospel was contained in a letter supposedly written by the fourth-century church leader Clement of Alexandria which was discovered in 1958 (and subsequently lost) by the American scholar Morton Smith. The gospel is purportedly Mark’s more ‘spiritual’ account of Jesus, including some stories not found in canonical Mark, e.g. one that sounds like the Lazarus story of John 11, another in which the man Mark 14:52 who fled away naked to Jesus for teaching. Other Gospels of particular interest include: ● various Jewish Christian gospels, such as The Gospel of the Nazarenes, The Gospel of the Ebionites, The Gospel of the Hebrews (the last resembling Matthew’s Gospel). These gospels only exist now in fragmentary form. _______________________________________________________ Sample from page 1, What does ‘gospel’ mean? GOOD NEWS OF AN EMPEROR The emperor Augustus is praised in an inscription from Priene (c. 9 BC): Providence… created… the most perfect good for our lives…filling him [Augustus] with virtue for the benefit of mankind, sending us and those after us a savior who put an end to war and established all things… and whereas the birthday of the god [i.e. Augustus] marked for the world the beginning of good tidings through his coming… Translation from N. Lewis & M. Reinhold, eds., Roman Civilization II, New York: Harper & Row, 1955, p. 64. Scholars have debated endlessly over the historical value of the Gospel of Thomas: some see it as rivaling the canonical Gospels in importance; most see it as at best a secondary source, of dubious value. Like other apocryphal gospels, Thomas is arguably… a) later than the canonical Gospels b) dependent – directly or indirectly – on the canonical Gospels c) reflecting the ideas of second-century Gnosticism What are the Gospels? – Page 4 of 5 SAN PEDRO COLLEGE – RELIGIOUS STUDIES 2 (intro to the new testament I) Supplementary Reading BIBLE GENRES How should the different genres of the Bible impact how we interpret God’s word? The Bible is a work of literature. Literature comes in different genres or categories based on style. And each genre is read and appreciated differently from another. For example, to confuse a work of science fiction with a medical textbook would cause many problems. They must be understood differently. In the same way, both science fiction and medical textbook must be understood and treated differently from poetry. Therefore, accurate exegesis and interpretation takes into consideration the purpose and style of a given book or passage of Scripture. In addition, some verses are meant figuratively, and proper discernment of these is enhanced by an understanding of genre. Inability to identify genre can lead to serious misunderstanding of Scripture. Main Literary Genres found in the Bible are: 1) LAW - the purpose of the law is to express God’s sovereign will concerning government, priestly duties, social responsibilities etc. - Examples: Leviticus and Deuteronomy 2) HISTORY - stories and epics from the Bible are included in this genre. Almost every book in the Bible contains some history. - Examples: Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, Joshua, Judges, 1st & 2nd Samuel, 1st & 2nd Kings, 1st & 2nd Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah and Acts 3) WISDOM - is the genre of aphorism that teaches the meaning of life and how to live. Some of the language used in wisdom literature is metaphorical and poetic and should be taken into account during analysis. - Examples: Proverbs, Job and Ecclesiastes 4) POETRY - are books of rhythmic prose, parallelism and metaphor. - Examples: Song of Solomon, Lamentations and Psalms - many of the psalms were written by David himself, a musician, or David’s worship leader. 6) EPISTLE - is a letter usually in a formal style. There are 21 letters in the New Testament from the apostles to various churches or individuals. - These letters have a style very similar to modern letters with an opening, a greeting, body and closing. - Content of the letter involves the following: a. clarification of prior teaching b. rebuke or admonition c. an explanation d. correction of false teaching e. a deeper dive into the teaching of Jesus - A reader may do well to understand the cultural, historical and social situation of the original recipients in order to get the most out of an analysis of these books. - Examples: Letters of Paul to the Romans, 1st and 2nd Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1st and 2nd Thessalonians; Letters of James, Peter, John and Jude 7) PROPHECY - includes predictions of future events, warning of coming judgments and an overview of God’s plan for Israel. - Examples: Old Testament book of Isaiah to Malachi; the book of Revelation - Apocalyptic Literature is a specific form of prophecy largely involving symbols and imagery in predicting disaster and destruction. We find this type of language in the following books: a. Daniel – the beast (Chapter 7) b. Ezekiel – the scroll (Chapter 3) c. Zechariah – the golden lampstand (Chapter 4) d. Revelation – the four horsemen (Chapter 6) The prophetic and apocalyptic books are the ones most often subjected to faulty exegesis and personal interpretation based on emotion or preconceived bias. Understanding the genres of Scripture is vital to the bible student. If the wrong genre is assumed for a passage, it can easily be misunderstood or misconstrued leading to an incomplete or fallacious understanding of what God desires to communicate. 5) NARRATIVE - this genre includes the Gospels which are biographical narratives about Jesus. Bits of other genre within the Gospels are parables and discourse. - Examples: books of Ruth, Esther and Jonah What are the Gospels? – Page 5 of 5