Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

www.elsevier.com/locate/jvb

A meta-analytic examination of the construct validity

of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire

Job Satisfaction Subscale

Nathan A. Bowling *, Gregory D. Hammond

Wright State University, Department of Psychology, 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway, Dayton, OH 45435-0001, USA

Received 21 December 2007

Available online 1 February 2008

Abstract

Although several different measures have been developed to assess job satisfaction, large-scale examinations of the psychometric properties of most satisfaction scales are generally lacking. In the current study we used meta-analysis to examine the construct validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale (MOAQJSS; [Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire.

Unpublished manuscript, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, G. D., & Klesh, J.

(1983). Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. In S. E. Seashore, E. E. Lawler, P. H. Mirvis, & C. Cammann

(Eds.), Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices (pp. 71–138). New York: Wiley-Interscience]), which is a brief, face-valid measure of global job satisfaction. Our analyses indicate that the MOAQ-JSS is a reliable and construct-valid measure of job satisfaction. We also report normative data for the MOAQ-JSS.

Ó 2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Job satisfaction; Construct validity; Meta-analysis

1. Introduction

The study of job satisfaction has a long history in industrial and organizational psychology (Wright, 2006),

where it is examined as a potential cause, correlate, and consequence of both work-related and non-work variables. A number of studies, for example, have examined the potential situational (Fisher & Gitelson, 1983;

Fried & Ferris, 1987; Jackson & Schuler, 1985; Loher, Noe, Moeller, & Fitzgerald, 1985) and dispositional

(Connolly & Viswesvaran, 2000; Judge & Bono, 2001) causes of job satisfaction and job satisfaction has been

examined as a potential cause of important work-related behaviors, such as job performance (Iaffaldano &

Muchinsky, 1985; Judge, Thoresen, Bono, & Patton, 2001; Petty, McGee, & Cavender, 1984), absenteeism

*

Corresponding author.

E-mail address: nathan.bowling@wright.edu (N.A. Bowling).

0001-8791/$ - see front matter Ó 2008 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.01.004

64

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

(Farrell & Stamm, 1988), and turnover (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Indeed, Spector (1997) observed that job satisfaction is the most widely-studied topic in industrial and organizational psychology.

Given its popularity as a research topic, it should be no surprise that several different measures have been

developed to assess job satisfaction. Unfortunately, there are few large-scale studies that examine the psychometric properties of these measures. One notable exception, however, is a meta-analysis by Kinicki, McKeeRyan, Schriesheim, and Carson (2002), which examined the construct validity of the Job Descriptive Index

(JDI; Smith, Kendall, & Hulin, 1969). Although Kinicki et al. found evidence that the JDI is a construct-valid

measure of facet satisfaction, we believe that efforts should be made to examine the validity of other job satisfaction measures. As we detail below, such research is especially needed in light of potentially serious limitations of the JDI. Thus, in the current study we provide a quantitative review of a job satisfaction measure

that avoids many of the JDI’s limitations. Specifically, we used meta-analysis to examine the reliability and

construct validity of the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale

(MOAQ-JSS; Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, & Klesh, 1979, 1983). We also compiled normative data for

the MOAQ-JSS. First, however, we briefly describe the nature of the MOAQ-JSS and discuss its history.

1.1. Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire

The MOAQ was developed as an alternative to the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS; Hackman & Oldham,

1980) and thus includes subscale that assess the variables identified by Hackman and Oldham’s (1976) Job

Characteristics Model (for reviews of the development and early history of the MOAQ see Cammann

et al., 1979, 1983). These variables include descriptions of the work environment (e.g., job characteristics), psychological states (e.g., experienced meaningfulness, feelings of responsibility), and employee responses (e.g.,

job satisfaction, motivation). In the current study, however, we focus exclusively on the Job Satisfaction Subscale of the MOAQ.

Scores on the MOAQ-JSS are computed using the average of the following three items (note that the second

item is reversed-scored):

‘‘All in all I am satisfied with my job.”

‘‘In general, I don’t like my job.”

‘‘In general, I like working here.”

Although the original version of the MOAQ-JSS used a 7-point agree–disagree scale (Cammann et al.,

1979, Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, & Klesh, 1983), some researchers have used 5-point (e.g., Allen, 2001;

Grandey, 2003) and 6-point (e.g., Brasher & Chen, 1999; Fox & Spector, 1999) versions of the measure.

1.2. Advantages of the MOAQ-JSS over other job satisfaction measures

One obvious advantage of the MOAQ-JSS is its length. While the MOAQ-JSS consists of only three items,

other popular job satisfaction scales are generally much longer. The JDI (Smith et al., 1969), for example,

includes 72 items, while the long-form and short-form of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ;

Weiss, Dawis, England, & Lofquist, 1967) include 100 items and 20 items, respectively. Thus, the MOAQJSS can be especially useful when concerns about questionnaire length make longer job satisfaction measures

impractical.

The MOAQ-JSS also offers an advantage over other job satisfaction measures in that it is a face-valid measure of the affective component of job satisfaction. This is important because definitions of job satisfaction

have generally described it as including an affective or emotional component (Brief, 1998; Brief & Roberson,

1989; Organ & Near, 1985). Job satisfaction, in other words, involves not only one’s thoughts but also one’s

feelings about his or her job. Each of the three MOAQ-JSS items, for example, includes either the word ‘‘satisfied” or ‘‘like,” which can be described as being affective or emotion-oriented words. This is in contrast to

other measures, such as the JDI, which have been criticized for not adequately assessing employee affect (Brief,

1998; Brief & Roberson, 1989; Organ & Near, 1985).

Finally, we should also note that the MOAQ-JSS assesses a different construct than those assessed by the

JDI subscales. While the JDI assesses specific facets of job satisfaction (i.e., satisfaction with work itself,

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

65

supervision, co-workers, pay, and promotional opportunities), the MOAQ-JSS assesses global job satisfaction.

Although the JDI research group developed a measure of global job satisfaction (the Job In General Scale or

JIG; Ironson, Smith, Brannick, Gibson, & Paul, 1989) many years after the introduction of the original JDI,

this general measure was not examined in the Kinicki et al. (2002) meta-analysis. Thus, although research by

Kinicki et al. on the validity of the JDI provides a useful contribution to the literature, it is important to examine the construct validity of other job satisfaction measures, such as the MOAQ-JSS.

In the next section we develop a nomological network (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955) for the global job satisfaction construct. Using this network as a guide, we conducted a meta-analysis that examined the construct

validity of the MOAQ-JSS.

2. A nomological network for job satisfaction

In order to examine the construct validity of a measure, it is important to first specify a nomological network for the construct of interest (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). That is, one should identify a pattern of relationships that theoretically exist between the given construct and several external variables. One can conclude

that a specific measure is construct-valid if it yields a pattern of relationships with external variables that is

similar to the pattern specified by the nomological network.

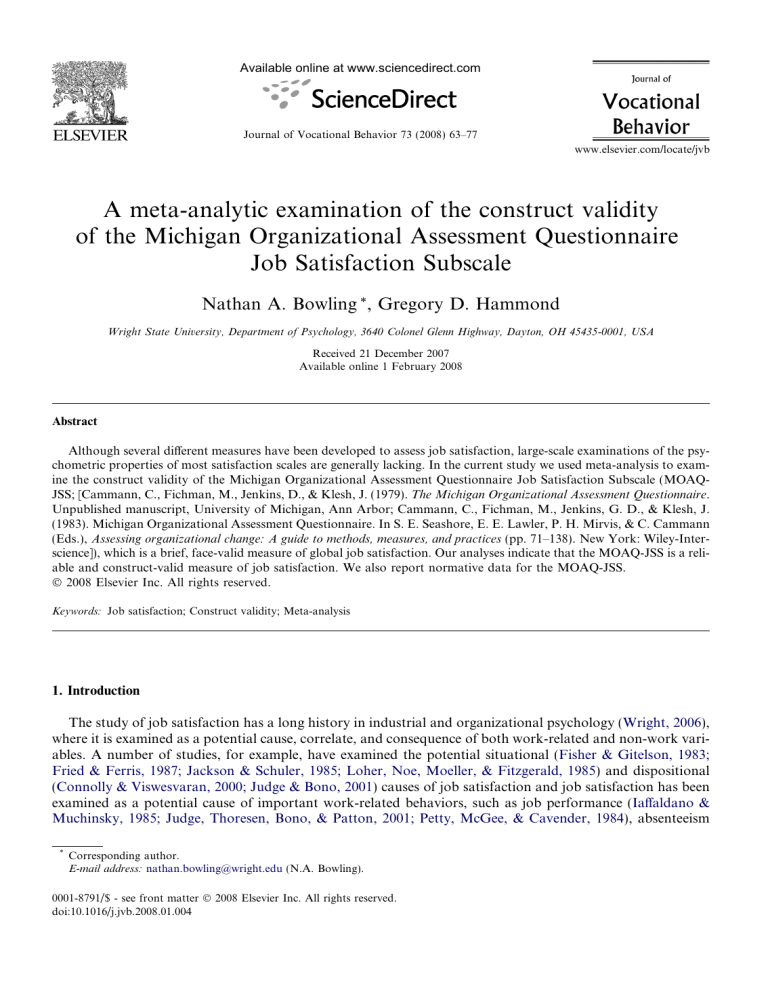

In the current section we present a nomological network that identifies the hypothesized causes, correlates,

and consequences of job satisfaction (see Fig. 1). This network is based on decades of theoretical and empirical

work that examines the job satisfaction construct (for reviews of the job satisfaction literature see Brief, 1998;

Spector, 1997) and is not intended to represent a comprehensive theory of job satisfaction.

Our subsequent meta-analysis examined whether the MOAQ-JSS yields a pattern of relationships similar to that

predicted in the nomological network. We should note that Kinicki et al. (2002) used a similar strategy in examining

the construct validity of the JDI. Their work largely forms the basis for the approach used in the current study.

2.1. Hypothesized antecedents of job satisfaction

2.1.1. Job characteristics

Job characteristics, which are a reflection of the complexity of one’s work tasks, have long been established both theoretically and empirically as a potentially important cause of job satisfaction. More specifHypothesized Correlates

Hypothesized Antecedents

Job Complexity (+)

Skill Variety

Task Identity

Task Significance

Autonomy

Feedback

Stressors (-)

Role Conflict

Role Ambiguity

Role Overload

Organizational Constraints

Interpersonal Conflict

Work-Family Conflict

Social and Organizational Support (+)

Person-Environment Fit (+)

Job Attitudes (+)

Facet Satisfaction

Organizational Commitment

Job Involvement

Career Satisfaction

Organizational Justice

Strains (-)

Job Tension

Anxiety

Depression

Emotional Exhaustion

Frustration

Physical Strains

Life Satisfaction (+)

Hypothesized Consequences

JOB

SATISFACTION

Job Performance (+)

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (+)

Counterproductive Work Behavior (-)

Employee Withdrawal (-)

Turnover Intentions

Turnover

Absenteeism

Fig. 1. Nomological network of hypothesized antecedents, correlates, and consequences of job satisfaction.

66

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

ically, the Job Characteristics Model (JCM; Hackman & Oldham, 1976, 1980) suggests that job complexity, which includes skill variety, task identify, task significance, autonomy, and feedback, is positively associated with job satisfaction. Consistent with the JCM, research has found considerable support for the

relationships between job characteristics and satisfaction (Fried & Ferris, 1987; Loher et al., 1985).

2.1.2. Work stressors

Work stressors, which are any aspects of one’s work environment that have the potential to cause mental or

physical illness (Jex, Beehr, & Roberts, 1992), are theoretically and empirically related to job satisfaction.

Research and theory suggest, for example, that stressors such as role ambiguity and role conflict (Fisher &

Gitelson, 1983; Jackson & Schuler, 1985), role overload (Spector & Jex, 1998), organizational constraints

(Spector & Jex, 1998), work–family conflict (Kossek & Ozeki, 1998), and interpersonal conflict (Bowling &

Beehr, 2006; Lapierre, Spector, & Leck, 2005) are all negatively associated with job satisfaction.

2.1.3. Social and organizational support

The receipt of support from one’s supervisors, co-workers, or organization has been widely examined as a

potential cause of job satisfaction. Research has consistently found positive relationships between both social

support and perceived organizational support and satisfaction (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Viswesvaran,

Sanchez, & Fisher, 1999).

2.1.4. Person–environment fit

Person–environment fit is the degree of compatibility between an employee and his or her work environment (Kristof, 1996). Theoretically, a good fit between what an employee wants or needs and what the

organization or job actually supplies is expected to contribute to one’s level of satisfaction. Consistent

with this hypothesis, previous research has established a strong positive relationship between person–environment fit and job satisfaction (Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, & Johnson, 2005; Verquer, Beehr, & Wagner, 2003).

2.2. Hypothesized correlates of job satisfaction

2.2.1. Job attitudes

Previous research suggests that job satisfaction yields positive relationships with other job attitudes, such as

organizational commitment (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002), job

involvement (Brown, 1996), and career satisfaction (Bowling, Beehr, & Lepisto, 2006). Confirmatory factor

analyses (CFA) further suggest that these attitudes are distinct from each other (Brooke, Russell, & Price,

1988; Mathieu & Farr, 1991). Thus, job satisfaction is related to but not redundant with other job attitudes.

Given the results of prior meta-analyses that have examined job satisfaction (Brown, 1996; Mathieu & Zajac,

1990; Meyer et al., 2002), we expected that the MOAQ-JSS will yield especially strong relationships with all

job attitudes except continuance commitment.

2.2.2. Organizational justice

Organizational justice includes several sub-dimensions, including distributive, procedural, and interactional justice (Colquitt, 2001). Research and theory suggest that each of these sub-dimensions is positively

related to job satisfaction (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001; Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, & Ng,

2001).

2.2.3. Psychological and physical strains

Strains represent the psychological (e.g., anxiety, burnout, etc.) or physical (e.g., headaches, upset stomach,

etc.) illness that results from being exposed to stressors (Jex et al., 1992) and are typically found to yield negative relationships with job satisfaction (e.g., Sanchez & Viswesvaran, 2002; Spector & Jex, 1991; Tepper,

2000). Because job satisfaction is generally defined as including an affective component (Brief, 1998), emotion-oriented strains, such as anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, and frustration, should yield

especially strong relationships with satisfaction.

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

67

2.2.4. Life satisfaction

Research and theory suggest that job satisfaction is positively related to non-work attitudes, such as life

satisfaction (Tait, Padgett, & Baldwin, 1989). This is likely to occur because emotions experienced in one life

domain (e.g., work) ‘‘spill over” into other life domains (e.g., life in general; Judge & Watanabe, 1994).

2.3. Hypothesized consequences of job satisfaction

2.3.1. In-role performance

Much theoretical and empirical attention has been given to the consequences of job satisfaction. Several

studies, for instance, have examined in-role job performance as a potential consequence of satisfaction

(Iaffaldano & Muchinsky, 1985; Judge et al., 2001; Petty et al., 1984). Satisfaction, for instance, has been

hypothesized to influence in-role performance via effects on employee motivation (Strauss, 1968). Consistent

with this, research has consistently found a positive relationship between satisfaction and in-role performance

(Iaffaldano & Muchinsky, 1985; Judge et al., 2001; Petty et al., 1984).

2.3.2. Extra-role performance

In response to the modest findings yielded by research on the satisfaction–performance relationship, some

researchers have advocated the broadening of the performance domain to include extra-role behaviors

(Borman & Motowidlo, 1993; Brief, 1998). These researchers reason that because in-role performance is often

closely managed by organizations, then satisfaction should not be strongly related to in-role performance.

That is, given the situational constraints created by organizations to encourage effective in-role performance,

dissatisfied employees will often avoid withholding performance even if they desire to. On the other hand,

extra-role behaviors, such as organizational citizenship behavior (OCBs; Smith, Organ, & Near, 1983) and

counterproductive work behavior (CWBs; Chen & Spector, 1992) are voluntary in nature. Thus, the decision

to engage or not engage in OCBs and CWBs is largely based on the discretion of the individual employee. For

this reason, satisfaction is expected to yield positive relationships with OCBs and negative relationships with

CWBs and these relationships are expected to be stronger than those found between satisfaction and in-role

performance. Consistent with this reasoning, meta-analyses have found that satisfaction yields significant relationships with both OCBs and CWBs (Dalal, 2005; LePine, Erez, & Johnson, 2002; Organ & Ryan, 1995).

2.3.3. Withdrawal behavior

In addition to being a potential predictor of in-role and extra-role performance, job satisfaction is theoretically

and empirically linked to several forms of withdrawal behavior. These behaviors include absenteeism (Farrell &

Stamm, 1988) as well as turnover intention and actual turnover (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Given the findings of prior

job satisfaction research (Tett & Meyer, 1993), the relationship between the MOAQ-JSS and turnover intention is

expected to be especially strong. In explaining these relationships, researchers have theorized that withdrawal

behaviors are a strategy used by workers to avoid unpleasant or dissatisfying work (Hanisch & Hulin, 1991).

In sum, we used meta-analysis to examine the reliability and construct validity of the MOAQ-JSS. Specifically,

we examined whether the MOAQ-JSS yields a pattern of relationships consistent with that described above in the

nomological network and presented in Fig. 1. We also compiled normative data for the MOAQ-JSS.

3. Method

We used meta-analysis to examine the psychometric properties of the Michigan Organizational Assessment

Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale (MOAQ-JSS; Cammann et al., 1979, 1983). Below, we discuss our

literature search strategy and the methods used to examine the reliability and construct validity of the

MOAQ-JSS. We also describe the methods used to compile the normative data.

3.1. Literature search

We first searched the PsycINFO database using the keywords ‘‘job satisfaction.” Given the size of the job

satisfaction literature, it was impractical to examine every article that was identified using ‘‘job satisfaction” as

68

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

the search term (a December 20, 2007 search of the PsycINFO database using the key words ‘‘job satisfaction”

yielded a total of 21,968 sources published between 1979 and 2007). Thus, we limited our initial literature

search to articles published between 1979 (i.e., the year Cammann et al. first introduced the MOAQ) and

2007 in the following journals: Academy of Management Journal, Administrative Science Quarterly, Journal

of Applied Psychology, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, and Personnel Psychology.

We chose these particular journals because Kinicki et al. (2002) limited their search to the same sources.

Although we concede that several studies using the MOAQ-JSS are likely to appear in other journals, it

was necessary to limit this initial search due to the size of the job satisfaction literature. We conducted additional PsycINFO searches using the key words ‘‘Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire” and we

also searched for articles that mentioned the name ‘‘Cammann” in their reference section. These later searches

were not limited to any particular journals, and thus we identified articles to add to our database that were

published in several additional journals (e.g., Journal of Management, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Journal of Organizational Behavior, and Journal

of Vocational Behavior).

In an effort to identify additional MOAQ-JSS samples, we reviewed each article found via the above PsycINFO searches. This yielded additional samples, because articles found in the PsycINFO searches often cited

additional MOAQ-JSS studies that we had not previously identified.

3.2. Inclusion criteria

After identifying potentially relevant studies, we closely reviewed each to ensure that they used the original

MOAQ-JSS. We excluded some studies from our database because they either adapted the MOAQ-JSS to laboratory tasks (e.g., Douthitt & Aiello, 2001), modified one or more MOAQ-JSS items (e.g., Duffy & Shaw,

2000), did not use all three MOAQ-JSS items (e.g., Vandenberg, Richardson, & Eastman, 1999), or because

they combined the MOAQ-JSS with other measures of job satisfaction (e.g., Barsky, Thoresen, Warren, &

Kaplan, 2004). We also excluded studies that translated the MOAQ-JSS into languages other than English,

since there were too few studies using any single non-English language to make meta-analysis feasible. We also

excluded studies that adapted the MOAQ-JSS for use in non-employee samples. These criteria yielded a final

total of 80 samples (overall N = 30,703) that used the MOAQ-JSS.

3.3. Analyses examining the reliability of the MOAQ-JSS

To examine the reliability of the MOAQ-JSS, we used methods similar to those of Kinicki et al. (2002).

First, we computed the mean internal consistency reliabilities (coefficient alpha) for the MOAQ-JSS. We also

computed the range of internal consistency reliabilities across samples. Similar analyses were conducted for

the test–retest reliability of the MOAQ-JSS. In examining the reliability of the MOAQ-JSS, we computed both

sample-weighted and un-weighted statistics.

3.4. Analyses examining the construct validity of the MOAQ-JSS

We used Hunter and Schmidt’s (2004) method to conduct meta-analyses examining the construct validity of

the MOAQ-JSS. We computed sample-weighted mean correlations corrected for unreliability in both the

MOAQ-JSS and its hypothesized antecedents/correlates/consequences. We corrected the correlations individually when all reliability data were available. Artifact distributions were used to estimate missing reliabilities.

We used Wanous, Reichers, and Hudy’s (1997) meta-analytic reliability estimate to correct for unreliability in

single-item turnover intention measures and Viswesvaran, Ones, and Schmidt’s (1996) meta-analytic reliability

estimate to correct for inter-rater reliability in job performance ratings.

3.5. Normative data for the MOAQ-JSS

Finally, we computed normative means and standard deviations for the MOAQ-JSS. We calculated both

un-weighted and sample-weighted normative data.

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

69

4. Results

4.1. Reliability of the MOAQ-JSS

Table 1 reports analyses examining the internal consistency and test–retest reliabilities of the Michigan

Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale (MOAQ-JSS). As displayed in the table,

we found that the MOAQ-JSS yielded acceptable levels of reliability. Specifically, the mean sample-weighted

internal consistency reliability was.84 (k = 79, N = 30,623) and the mean sample-weighted test–retest reliability was .50 (k = 4, N = 746).

4.2. Construct validity of the MOAQ-JSS

4.2.1. Hypothesized antecedents of job satisfaction

Table 2 presents meta-analyses examining the relationships between the hypothesized antecedents of job

satisfaction and the MOAQ-JSS.

These analyses found that job complexity (q = .46, k = 5, N = 877), skill variety (q = .28, k = 3, N = 725),

task identity (q = .28, k = 3, N = 725), task significance (q = .17, k = 3, N = 725) autonomy (q = .35, k = 13,

N = 2984), and feedback (q = .46, k = 3, N = 725) were each positively related to the MOAQ-JSS. Work

stressors, on the other hand, were negatively associated with the MOAQ-JSS. Specifically, role ambiguity

(q = .42, k = 14, N = 3060), role conflict (q = .32, k = 12, N = 3164), organizational constraints

(q = .39, k = 8, N = 1690), interpersonal conflict (q = .29, k = 18, N = 7634), work–family conflict

(q = .41, k = 3, N = 1204), work to family conflict (q = .21, k = 6, N = 1787) and family to work conflict

(q = .13, k = 5, N = 1493) each yielded negative relationships.

Finally, the table shows that supervisor social support (q = .47, k = 6, N = 1616), co-worker social support

(q = .33, k = 4, N = 703), perceived organizational support (q = .46, k = 4, N = 1084), and person–environment fit (q = .49, k = 3, N = 524) were all positively related to the MOAQ-JSS. Of the 18 hypothesized antecedents, the only one that did not yielded the expected relationship with the MOAQ-JSS was role overload

(q = .03, k = 12, N = 3259). As a whole, therefore, these results regarding the hypothesized causes of job

satisfaction are consistent with the nomological network.

4.2.2. Hypothesized correlates of job satisfaction

In Table 3 we report the results of meta-analyses examining the relationship between the MOAQ-JSS and

the hypothesized correlates of job satisfaction. As shown in the table, the MOAQ-JSS yielded positive relationships with other job attitudes. Specifically, satisfaction with work itself (q = .74, k = 2, N = 316), supervision (q = .57, k = 2, N = 316), co-workers (q = .40, k = 2, N = 316), pay (q = .43, k = 5, N = 1322),

promotional opportunities (q = .54, k = 3, N = 730), organizational commitment (q = .69, k = 9,

N = 3161), affective commitment (q = .77, k = 16, N = 8061), normative commitment (q = .52, k = 6,

N = 1626) continuance commitment (q = .05, k = 8, N = 2446), job involvement (q = .53, k = 5, N = 1627),

career satisfaction (q = .55, k = 2, N = 463), distributive justice (q = .44, k = 4, N = 896), procedural justice

(q = .54, k = 6, N = 3480), and interactional justice (q = .42, k = 3, N = 2946) each yielded positive relationships with the MOAQ-JSS.

We also found that the MOAQ-JSS was negatively associated with several strains, including job tension

(q = .42, k = 3, N = 654), anxiety (q = .15, k = 11, N = 4255), depression (q = .41, k = 6, N = 3693),

Table 1

Internal consistency and test–retest reliability for the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Scale

Internal-consistency reliability

Test–retest reliability

k

N

Un-weighted M

Sample-weighted M

Range

k

N

Un-weighted M

Sample-weighted M

Range

79

30,623

.85

.84

.67, .94

4

746

.49

.50

.40, .64

Note. k, number of samples; N, total sample size.

70

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

Table 2

Relationships between Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Satisfaction Scale and the hypothesized causes of job

satisfaction

Variable

k

N

Job complexity

Skill variety

Task identify

Task significance

Autonomy

Feedback

Role ambiguity

Role conflict

Role overload

Organizational constraints

Interpersonal conflict

Work–family conflict

Work–family conflict

Family–work conflict

Supervisor support

Co-worker support

Perceived organizational support

Person–environment fit

5

3

3

3

13

3

14

12

12

8

18

3

6

5

6

4

4

3

877

725

725

725

2984

725

3060

3164

3259

1690

7634

1204

1787

1493

1616

703

1084

524

Mean r

Mean q

SDq

.40

.23

.21

.10

.29

.35

.34

.26

.02

.33

.23

.36

.18

.11

.37

.27

.41

.44

.46

.28

.28

.17

.35

.46

.42

.32

.03

.39

.29

.41

.21

.13

.47

.33

.46

.49

.09

.05

.01

.08

.19

.05

.10

.22

.23

.08

.09

.00

.06

.06

.15

.28

.18

.13

Note. k, number of samples; N, total sample size; mean r, average weighted correlation coefficient; mean q, average weighted correlation.

Coefficient corrected for unreliability in both the predictor and criterion.

Table 3

Relationships between Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Satisfaction Scale and the hypothesized correlates of job

satisfaction

Variable

k

N

Satisfaction with work itself

Satisfaction with supervision

Satisfaction with co-workers

Satisfaction with pay

Satisfaction with promotional opportunities

Organizational commitment

Affective commitment

Normative commitment

Continuance commitment

Job involvement

Career satisfaction

Distributive justice

Procedural justice

Interactional justice

Job tension

Anxiety

Depression

Emotional exhaustion

Frustration

Generic psychological strains

Physical symptoms

Life satisfaction

2

2

2

5

3

9

16

6

8

5

2

4

6

3

3

11

6

5

12

5

13

3

316

316

316

1322

730

3161

8061

1626

2446

1627

463

896

3480

2946

654

4255

3693

898

2624

2566

4180

941

Mean r

Mean q

SDq

.62

.50

.36

.37

.47

.59

.64

.43

.04

.39

.45

.40

.45

.32

.33

.13

.32

.54

.36

.39

.18

.35

.74

.57

.40

.43

.54

.69

.77

.52

.05

.53

.55

.44

.54

.42

.42

.15

.41

.62

.45

.46

.22

.41

.07

.00

.22

.06

.05

.09

.03

.14

.11

.17

.00

.00

.08

.08

.00

.19

.01

.07

.04

.06

.08

.05

Note. k, number of samples; N, total sample size; mean r, average weighted correlation coefficient; mean q, average weighted correlation.

Coefficient corrected for unreliability in both the predictor and criterion.

emotional exhaustion (q = .62, k = 5, N = 898), frustration (q = .45, k = 12, N = 2624), general psychology strains (q = .46, k = 5, N = 2566), and physical symptoms (q = .22, k = 13, N = 4180). Finally, the

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

71

Table 4

Relationships between Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Satisfaction Scale and the hypothesized consequences of job

satisfaction

Variable

k

N

Job performance

Organizational citizenship behavior

Counterproductive work behavior

Turnover intension

Turnover

Absenteeism

12

8

3

31

7

5

2401

1555

874

12,618

3818

1180

Mean r

Mean q

SDq

.15

.17

.29

.52

.14

.12

.19

.21

.33

.65

.15

.13

.13

.07

.01

.16

.08

.00

Note. k, number of samples; N, total sample size; mean r, average weighted correlation coefficient; mean q, average weighted correlation.

Coefficient corrected for unreliability in both the predictor and criterion.

Table 5

Normative data for the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Measure

MOAQ-JSS

k

N

Un-Weighted M

Un-weighted SD

Sample-weighted M

Sample-weighted SD

5-point

6-point

7-point

18

8

36

7135

1865

15,234

3.93

4.70

5.48

0.83

1.20

1.31

3.87

4.70

5.40

0.82

1.19

1.37

Note. MOAQ-JSS, Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale; k, number of samples; N, total sample

size.

MOAQ-JSS was positively related to life satisfaction (q = .41, k = 3, N = 941). In sum, these findings regarding the relationships between the MOAQ-JSS and each of the 22 hypothesized correlates of job satisfaction are

consistent with the pattern depicted in Fig. 1.

4.2.3. Hypothesized consequences of job satisfaction

We conducted meta-analyses examining the relationships between the MOAQ-JSS and the hypothesized

consequences of job satisfaction (see Table 4). As hypothesized in Fig. 1, the MOAQ-JSS yielded positive relationships with in-role job performance (q = .19, k = 12, N = 2401) and organizational citizenship behaviors

(q = .21, k = 8, N = 1555), and negative relationships with counterproductive work behaviors (q = .33,

k = 3, N = 874), turnover intentions (q = .65, k = 31, N = 12,618), turnover (q = .15, k = 7, N = 3818),

and absenteeism (q = .13, k = 5, N = 1180).

4.3. MOAQ-JSS norms

Finally, we compiled norms for the MOAQ-JSS. Because some authors reported the sum of the 3 MOAQJSS items and others reported the average of the items, it was necessary for us to place all the descriptive statistics (i.e., means and standard deviations) form the primary studies on a common metric. Thus, we transformed the MOAQ-JSS descriptive statistics from studies that used the sum of the MOAQ-JSS items into

scores that represented the average of the MOAQ-JSS items. This was achieved by dividing the descriptive

statistics by 3 (i.e., the number of MOAQ-JSS items). As shown in Table 5, separate norms are reported

for the 5-, 6-, and 7-point versions of the MOAQ-JSS. Seventeen samples were excluded from these analyses

because the authors did not report the number of scale points they used for the MOAQ-JSS.

5. Discussion

The current study used meta-analysis to provide the largest and most comprehensive examination ever conducted of the psychometric properties of a global job satisfaction measure. Our analyses revealed important

findings concerning the reliability of the MOAQ-JSS. First, we found that the MOAQ-JSS yielded acceptable

levels of reliability (see Nunnally, 1978). We also found extensive evidence of the construct validity of the

72

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

MOAQ-JSS. Specifically, the MOAQ-JSS generally yielded a pattern of relationships with external variables

that is consistent with that identified in the nomological network (see Fig. 1). Job characteristics, social and

organizational support, and person–environment fit were positively related to and stressors were negatively

related to the MOAQ-JSS. Furthermore, the MOAQ-JSS was positively associated with other job attitudes

and with life satisfaction and negatively associated with strains. Finally, the MOAQ-JSS was positively related

to in-role performance and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), but was negatively associated with

counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs) and employee withdrawal.

In addition to noting that the direction of the correlations that we found for the MOAQ-JSS generally

matched those hypothesized in Fig. 1, it is also important to consider that the magnitude of the relationships

generally supported our predictions. The relationships for job attitudes and turnover intention, for instance,

were among the strongest relationships that we found. Continuance commitment was the only job attitude

found to be weakly related to the MOAQ-JSS. This overall pattern of results is consistent with past job satisfaction research (Brown, 1996; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Meyer et al., 2002; Tett & Meyer, 1993). Likewise, we

found some evidence that the MOAQ-JSS was more strongly related to extra-role performance (particularly

CWBs) than to in-role performance. This pattern is also consistent with past research (Brief, 1998).

Given such evidence that the MOAQ-JSS is a reliable and valid measure of global job satisfaction, it may in

many situations offer advantages over other popular measures of job satisfaction. First, the MOAQ-JSS consists of only three items. It might thus be preferred over longer satisfaction measures in instances where questionnaire length is a concern. Second, the MOAQ-JSS appears to better assess the affective component of job

satisfaction than does many other popular measures. This is important because scholars have generally

described job satisfaction as including an emotional response to one’s job (Brief, 1998; Brief & Roberson,

1989; Organ & Near, 1985). As discussed above in the introduction, some satisfaction measures, such as

the Job Descriptive Index (JDI; Smith et al., 1969) have been criticized for not effectively assessing the affective

component of job satisfaction (Brief, 1998; Brief & Roberson, 1989; Organ & Near, 1985). Because it contains

words such as ‘‘satisfaction” and ‘‘like,” the MOAQ-JSS is a face-valid measure of affective job satisfaction.

Furthermore, the current findings regarding the relatively strong relationships between the MOAQ-JSS and

emotion-related variables (i.e., affective commitment, job tension, depression, emotional exhaustion, and frustration) provide support for the affective nature of the MOAQ-JSS.

Finally, we reported normative data for the MOAQ-JSS. The mean MOAQ-JSS scores that we obtained

are consistent with the common research finding that most employees are satisfied with their jobs (Spector,

1997). Because they can help managers and researchers interpret MOAQ-JSS scores, these normative data

have important practical applications.

5.1. Limitations

Because nearly all of the primary studies used cross-section designs, the current study was unable to test

causal relationships. Furthermore, common-method variance may have influenced the correlations that we

found, since most of the primary studies exclusively used self-report data. Finally, it is likely that our literature

search may not have found all studies that have used the MOAQ-JSS. This may be particularly true because

our search focused exclusively on published research. We should note, however, that our literature search did

yield a large number of studies (k = 80) and a large overall sample size (N = 30,703).

6. Summary

In sum, we found evidence that the MOAQ-JSS is a reliable and construct-valid measure of job satisfaction.

We strongly encourage both researchers and practitioners to use the MOAQ-JSS to assess global job

satisfaction.

Acknowledgement

The authors which to thank Marsha Moss for assisting us with the literature search.

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

73

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis

*

Allen, T. D. (2001). Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58,

414–435.

*

Allen, T. D., Lentz, E., & Day, R. (2006). Career success outcomes associated with mentoring others: A comparison of mentors and

nonmentors. Journal of Career Development, 32, 272–285.

*

Ashforth, B. E., & Saks, A. M. (1996). Socialization tactics: Longitudinal effects of newcomer adjustment. Academy of Management

Journal, 39, 149–178.

*

Ashforth, B. E., Sluss, D. M., & Saks, A. M. (2007). Socialization tactics, proactive behavior, and newcomer learning: Integrating

socialization models. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70, 447–462.

Barsky, A., Thoresen, C. J., Warren, C. R., & Kaplan, S. A. (2004). Modeling negative affectivity and job stress: A contingency-based

approach. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 915–936.

*

Bartlett, K. R. (2001). The relationship between training and organizational commitment: A study in the health care field. Human

Resource Development Quarterly, 12, 335–352.

*

Beehr, T. A., Farmer, S. J., Glazer, S., Gudanowski, D. M., & Nair, V. N. (2003). The enigma of social support and occupational stress:

Source congruence and gender role effects. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8, 220–231.

*

Beehr, T. A., Glaser, K. M., Beehr, M. J., Beehr, D. E., Wallwey, D. A., Erofeev, D., et al. (2006). The nature of satisfaction with

subordinates: Its predictors and importance to supervisors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 1523–1547.

*

Beehr, T. A., Glaser, K. M., Canali, K. G., & Wallwey, D. A. (2001). Back to basics: Re-examination of demand-control theory of

occupational stress. Work & Stress, 15, 115–130.

Borman, W. C., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1993). Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In N. Schmitt

& W. C. Borman (Eds.), Personnel selection (pp. 71–98). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bowling, N. A., & Beehr, T. A. (2006). Workplace harassment from the victim’s perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 998–1012.

*

Bowling, N. A., Beehr, T. A., Johnson, A. L., Semmer, N. K., Hendricks, E. A., & Webster, H. A. (2004). Explaining

potential antecedents of workplace social support: Reciprocity or attractiveness?. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology

9, 339–350.

Bowling, N. A., Beehr, T. A., & Lepisto, L. R. (2006). Beyond job satisfaction: A five-year prospective analysis of the dispositional

approach to job attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 315–330.

*

Brasher, E. E., & Chen, P. Y. (1999). Evaluation of success criteria in job search: A process perspective. Journal of Occupational and

Organizational Psychology, 72, 57–70.

Brief, A. P. (1998). Attitudes in and around organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brief, A. P., & Roberson, L. (1989). Job attitude organization: An exploratory study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19, 717–727.

Brooke, P. P., Russell, D. W., & Price, J. L. (1988). Discriminant validation of measures of job satisfaction, job involvement, and

organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73, 139–145.

*

Brough, P., O’Driscoll, M. P., & Kalliath, T. J. (2005). The ability of ‘family friendly’ organizational resources to predict work–family

conflict and job and family satisfaction. Stress and Health, 21, 223–234.

Brown, S. P. (1996). A meta-analysis and review of organizational research on job involvement. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 235–255.

*

Brown, D. J., & Keeping, L. M. (2005). Elaborating the construct of transformational leadership: The role of affect. The Leadership

Quarterly, 16, 245–272.

*

Bruck, C. S., Allen, T. D., & Spector, P. E. (2002). The relation between work–family conflict and job satisfaction: A finer-grained

analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60, 336–353.

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, G. D., & Klesh, J. (1983). Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. In S. E. Seashore, E.

E. Lawler, P. H. Mirvis, & C. Cammann (Eds.), Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices

(pp. 71–138). New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. Unpublished

manuscript, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

*

Carless, S. A., & Bernath, L. (2007). Antecedents of intent to change careers among psychologists. Journal of Career Development, 33,

183–200.

*

Carlson, D. S., & Kacmar, K. M. (2000). Work–family conflict in the organization: Do life role values make a difference? Journal of

Management, 26, 1031–1054.

*

Carlson, D. S., & Perrewé, P. L. (1999). The role of social support in the stressor–strain relationship: An examination of work–family

conflict. Journal of Management, 25, 513–540.

*

Chen, P. Y., & Spector, P. E. (1991). Negative affectivity as the underlying cause of correlations between stressors and strains. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 76, 398–407.

*

Chen, P. Y., & Spector, P. E. (1992). Relationships of work stressors with aggression, withdrawal, theft and substance use: An

exploratory study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 65, 177–184.

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes, 86, 278–321.

74

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology,

86, 386–400.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of

25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425–445.

Connolly, J. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2000). The role of affectivity in job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences,

29, 265–281.

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 281–302.

Dalal, R. S. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1241–1255.

*

Diefendorff, J. M., & Richard, E. M. (2003). Antecedents and consequences of emotional display rule perceptions. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 88, 284–294.

*

Diefendorff, J. M., Richard, E. M., & Gosserand, R. H. (2006). Examination of situational and attitudinal moderators of the hesitation

and performance relation. Personnel Psychology, 59, 365–393.

Douthitt, E. A., & Aiello, J. R. (2001). The role of participation and control in the effects of computer monitoring on fairness perceptions,

task satisfaction, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 867–874.

*

Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C., Shaw, J. D., Johnson, J. L., & Pagon, M. (2006). The social context of undermining behavior at work.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 101, 105–126.

Duffy, M. K., & Shaw, J. D. (2000). The Salieri Syndrome: Consequences of envy in groups. Small Group Research, 31, 3–23.

*

Eby, L. T. (2001). The boundaryless career experiences of mobile spouses in dual-earner marriages. Group & Organization Management,

26, 343–368.

*

Eby, L. T., & Russell, J. E. A. (2000). Predictors of employee willingness to relocate for the firm. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 57,

42–61.

*

Egan, T. M., Yang, B., & Bartlett, K. R. (2004). The effects of organizational learning culture and job satisfaction on motivation to

transfer learning and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15, 279–301.

*

Farmer, S. J., Beehr, T. A., & Love, K. G. (2003). Becoming an undercover police officer: A note on fairness perceptions, behavior, and

attitudes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 373–387.

Farrell, D., & Stamm, C. L. (1988). Meta-analysis of the correlates of employee absence. Human Relations, 41, 211–227.

Fisher, C. D., & Gitelson, R. (1983). A meta-analysis of the correlates of role conflict and ambiguity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68,

320–333.

*

Fortunato, V. J. (2004). A comparison of the construct validity of three measures of negative affectivity. Educational and Psychological

Measurement, 64, 271–289.

*

Fox, S., & Spector, P. E. (1999). A model of work frustration–aggression. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 915–931.

*

Fox, S., Spector, P. E., Goh, A., & Bruursema, K. (2007). Does your coworker know what you’re doing? Convergence of self- and peerreports of counterproductive work behavior. International Journal of Stress Management, 14, 41–60.

Fried, Y., & Ferris, G. R. (1987). The validity of the Job Characteristics Model: A review and meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 40,

287–322.

*

Golden, T. D. (2006). The role of relationships in understanding telecommuter satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27,

319–340.

*

Golden, T. D., & Veiga, J. F. (2005). The impact of extent of telecommuting on job satisfaction: Resolving inconsistent findings. Journal

of Management, 31, 301–318.

*

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When ‘‘the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peerrated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 86–96.

*

Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G. M., & Steiner, D. D. (2005). Must ‘‘service with a smile” be stressful? The moderating role of personal control

for American and French Employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 893–904.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes, 16, 250–279.

Hanisch, K. A., & Hulin, C. L. (1991). General attitudes and organizational withdrawal: An evaluation of a causal model. Journal of

Vocational Behavior, 39, 110–128.

*

Harris, K. J., & Kacmar, K. M. (2006). Too much of a good thing: The curvilinear effect of leader-member exchange on stress. The

Journal of Social Psychology, 146, 65–84.

*

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., & Witt, L. A. (2005). An examination of the curvilinear relationship between leader-member exchange and

intent to turnover. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 363–378.

*

Harvey, P., Harris, R. B., Harris, K. J., & Wheeler, A. R. (2007). Attenuating the effects of social stress: The impact of political skill.

Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 105–115.

*

Hochwarter, W. A., Perrewé, P. L., Ferris, G. R., & Brymer, R. A. (1999). Job satisfaction and performance: The moderating effects of

value attainment and affective disposition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 296–313.

*

Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., & Tidd, S. T. (2002). The relationship between work status congruence and work-related attitudes and

behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 903–915.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings (2nd ed.). Newbury Park,

CA: Sage.

Iaffaldano, M. T., & Muchinsky, P. M. (1985). Job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 97, 251–273.

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

75

Ironson, G. H., Smith, P. C., Brannick, M. T., Gibson, W. M., & Paul, K. B. (1989). Construction of a job in general scale: A comparison

of global, composite and specific measures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 1–8.

Jackson, S. E., & Schuler, R. S. (1985). A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work

settings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 16–78.

*

Jex, S. M., Adams, G. A., Elacqua, T. C., & Bachrach, D. G. (2002). Tape A as a moderator of stressors and job complexity: A

comparison of achievement strivings and impatience-irritability. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 977–996.

*

Jex, S. M., Beehr, T. A., & Roberts, C. K. (1992). The meaning of occupational stress items to survey respondents. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 77, 623–628.

*

Jex, S. M., & Gudanowski, D. M. (1992). Efficacy beliefs and work stress: An exploratory study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13,

509–517.

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationships of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and

emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 80–92.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and

quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 376–407.

Judge, T. A., & Watanabe, S. (1994). Individual differences in the nature of the relationship between job and life satisfaction. Journal of

Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67, 101–107.

*

Kickul, J., Lester, S. W., & Finkl, J. (2002). Promise breaking during radical organizational change: Do justice interventions make a

difference?. Journal of Organizational Behavior 23, 469–488.

*

Kim, J. C., & Cunningham, G. B. (2005). Moderating effects of organizational support on the relationship between work experiences and

job satisfaction among university coaches. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 36, 50–64.

Kinicki, A. J., McKee-Ryan, F. M., Schriesheim, C. A., & Carson, K. P. (2002). Assessing the construct validity of the Job Descriptive

Index: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of applied Psychology, 87, 14–32.

Kossek, E. E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work–family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for

organizational behavior-human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 139–149.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person–organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel

Psychology, 49, 1–49.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individual’s fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–

job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342.

Lapierre, L. M., Spector, P. E., & Leck, J. D. (2005). Sexual versus nonsexual workplace aggression and victims’ overall job satisfaction: A

meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 155–169.

LePine, J. A., Erez, E., & Johnson, D. E. (2002). The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review

and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 52–65.

*

Liu, C., Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (2005). The relation of job control with job strains: A comparison of multiple data sources. Journal of

Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 325–336.

*

Liu, C., Spector, P. E., & Shi, L. (2007). Cross-national job stress: A quantitative and qualitative study. Journal of Organizational

Behavior, 28, 209–239.

Loher, B. T., Noe, R. A., Moeller, N. L., & Fitzgerald, M. P. (1985). A meta-analysis of the relation of job characteristics to job

satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70, 280–289.

Mathieu, J. E., & Farr, J. L. (1991). Further evidence for the discriminant validity of measures of organizational commitment, job

involvement and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 127–133.

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational

commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 171–194.

*

McLain, D. L. (1995). Responses to health and safety risk in the work environment. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 1726–1743.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance and normative commitment to the

organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20–52.

*

Miner-Rubino, K., & Cortina, L. M. (2007). Beyond targets: Consequences of vicarious exposure to misogyny at work. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 92, 1254–1269.

*

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict

voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 1102–1121.

*

Moore, S., Grunberg, L., & Greenberg, E. (2000). The relationships between alcohol problems and well-being, work attitudes, and

performance: Are they monotonic? Journal of Substance Abuse, 11, 183–204.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

*

Nurick, A. J. (1982). Participation in organizational change: A longitudinal field study. Human Relations, 35, 413–430.

Organ, D. W., & Near, J. P. (1985). Cognition vs affect in measures of job satisfaction. International Journal of Psychology, 20, 241–253.

Organ, D. W., & Ryan, K. (1995). A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship

behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48, 775–802.

*

Ostroff, C., & Clark, M. A. (2001). Maintaining an internal market: Antecedents of willingness to change jobs. Journal of Vocational

Behavior, 59, 425–453.

*

Penney, L. M., & Spector, P. E. (2005). Job stress, incivility, and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The moderating role of

negative affectivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 777–796.

*

Perrewé, P. L., Hochwarter, W. A., & Kiewitz, C. (1999). Value attainment: An explanation for the negative effects of work–family

conflict on job and life satisfaction. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4, 318–326.

76

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

Petty, M. M., McGee, G. W., & Cavender, J. W. (1984). A meta-analysis of the relationships between individual job satisfaction and

individual performance. Academy of Management Review, 9, 712–721.

*

Premeaux, S. F., Adkins, C. L., & Mossholder, K. W. (2007). Balancing work and family: A field study of multi-dimensional, multi-role

work–family conflict. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28, 705–727.

*

Randall, M. L., Cropanzano, R., Bormann, C. A., & Birjulin, A. (1999). Organizational politics and organizational support as predictors

of work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 159–174.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87,

698–714.

*

Rotondo, D. M., & Perrewé, P. L. (2000). Coping with a career plateau: An empirical examination of what works and what doesn’t.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 2622–2646.

*

Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 600–619.

*

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (1997). A longitudinal investigation of the relationships between job information sources, applicant

perceptions of fit, and work outcomes. Personnel Psychology, 50, 395–426.

*

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2000). The role of dispositions, entry stressors, and behavioral plasticity theory in predicting newcomers’

adjustment to work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 43–62.

*

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2002). Is job search related to employment quality? It all depends on fit. Journal of Applied Psychology,

87, 646–654.

*

Sanchez, J. I., Kraus, E., White, S., & Williams, M. (1999). Adopting high-involvement human resource practices: The mediating role of

benchmarking. Group & Organization Management, 24, 461–478.

*

Sanchez, J. I., & Viswesvaran, C. (2002). The effects of temporal separation on the relations between self-reported work stressors and

strains. Organizational Research Methods, 5, 173–183.

*

Seibert, S. E., Silver, S. R., & Randolph, W. A. (2004). Taking empowerment to the next level: A multiple-level model of empowerment,

performance, and satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 332–349.

*

Senter, J. L., & Martin, J. E. (2007). Factors affecting the turnover of different groups of part-time workers. Journal of Vocational

Behavior, 71, 45–68.

*

Siegall, M., & McDonald, T. (1995). Focus of attention and employee reactions to job change. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25,

1121–1141.

*

Sikorska-Simmons, E. (2005). Predictors of organizational commitment among staff in assisted living. The Gerontologist, 45, 196–205.

*

Sinclair, R. R., Martin, J. E., & Croll, L. W. (2002). A threat-appraisal perspective on employees’ fears about antisocial workplace

behavior. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 37–56.

Smith, P. C., Kendall, L., & Hulin, C. L. (1969). The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement: A strategy for the study of

attitudes. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Smith, C. A., Organ, D. W., & Near, J. P. (1983). Organizational citizenship: Its nature and antecedents. Journal of Applied Psychology,

68, 653–663.

*

Sosik, J. J., & Godshalk, V. M. (2004). Self-other ratings agreement in mentoring: Meeting protégé expectations for development and

career advancement. Group & Organization Management, 29, 442–469.

*

Spector, P. E. (1991). Confirmatory test of a turnover model utilizing multiple data sources. Human Performance, 4, 221–230.

Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Applications, assessment, causes and consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

*

Spector, P. E., Chen, P. Y., & O’Connell, B. J. (2000). A longitudinal study of relations between job stressors and job strains while

controlling for prior negative affectivity and strains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 211–218.

*

Spector, P. E., Dwyer, D. J., & Jex, S. M. (1988). Relation of job stressors to affective, health, and performance outcomes: A comparison

of multiple data sources. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73, 11–19.

*

Spector, P. E., & Fox, S. (2003). Reducing subjectivity in the assessment of the job environment: Development of the Factual Autonomy

Scale (FAS). Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 417–432.

*

Spector, P. E., Fox, S., Penney, L. M., Bruursema, K., Goh, A., & Kessler, S. (2006). The dimensionality of counterproductivity: Are all

counterproductive behaviors created equal? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 446–460.

*

Spector, P. E., Fox, S., & Van Katwyk, P. T. (1999). The of negative affectivity in employee reactions to job characteristics: Bias effect or

substantive effect? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 205–218.

*

Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1991). Relations of job characteristics from multiple data sources with employee affect, absence, turnover

intentions, and health. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 46–53.

Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1998). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at Work

Scale, Organizational Constraints Scale, Quantitative Workload Inventory, and Physical Symptoms Inventory. Journal of Occupational

Health Psychology, 3, 356–367.

*

Spector, P. E., & O’Connell, B. J. (1994). The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control and Type A to the

subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67, 1–11.

*

Spector, P. E., Sanchez, J. I., Siu, O. L., Salgado, J., & Ma, J. (2004). Eastern versus Western control beliefs at work: an investigation of

secondary control, socioinstrumental control, and work locus of control in China and the US. Applied Psychology: An International

Review, 53, 38–60.

*

Spreitzer, G. M., Kizilos, M. A., & Nason, S. W. (1997). A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment

and effectiveness, satisfaction and strain. Journal of Management, 23, 679–704.

Strauss, G. (1968). Human relations—1968 style. Industrial Relations, 7, 262–276.

N.A. Bowling, G.D. Hammond / Journal of Vocational Behavior 73 (2008) 63–77

77

Tait, M., Padgett, M. Y., & Baldwin, T. T. (1989). Job and life satisfaction: a reevaluation of the strength of the relationship and gender

effects as a function of the date of the study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 502–507.

*

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178–190.

*

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Hoobler, J., & Ensley, M. D. (2004). Moderators of the relationships between coworkers’ organizational

citizenship behavior and fellow employees’ attitudes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 455–465.

Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analysis based on

meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46, 259–293.

*

Tidd, S. T., & Friedman, R. A. (2002). Conflict style and coping with role conflict: An extension of the uncertainty model of work stress.

The International Journal of Conflict Management, 13, 236–257.

Vandenberg, R. J., Richardson, H. A., & Eastman, L. J. (1999). The impact of high involvement work processes on organizational

effectiveness: A second-order latent variable approach. Group & Organization Management, 24, 300–339.

*

Van Katwyk, P. T., Fox, S., Spector, P. E., & Kelloway, E. K. (2000). Using the Job-Related Affective Well-Being Scale (JAWS) to

investigate affective responses to work stressors. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 219–230.

Verquer, M. L., Beehr, T. A., & Wagner, S. H. (2003). A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and job attitudes.

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63, 473–489.

Viswesvaran, C., Ones, D. S., & Schmidt, F. L. (1996). Comparative analysis of the reliability of job performance ratings. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 81, 557–574.

Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J. I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of

Vocational Behavior, 54, 314–334.

*

Wanberg, C. R., & Banas, J. T. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of openness to change in a reorganizing workplace. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 85, 132–142.

*

Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 85, 373–385.

*

Wanberg, C. R., Kanfer, R., & Banas, J. T. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of networking intensity among unemployed job seekers.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 491–503.

Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied

Psychology, 82, 247–252.

Weiss, D. J., Dawis, R. V., England, G. W., & Lofquist, L. H. (1967). Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota, Industrial Relations Center.

*

Wheeler, A. R., Gallagher, V. C., Brouer, R. L., & Sablynski, C. J. (2007). When person–organization (mis)fit and (dis)satisfaction lead to

turnover: The moderating role of perceived job mobility. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 203–219.

Wright, T. A. (2006). The emergence of job satisfaction in organizational behavior: A historical overview of the dawn of job attitude

research. Journal of Management History, 12, 262–277.

*

Zalesny, M. D., & Farace, R. V. (1987). Traditional versus open offices: A comparison of sociotechnical, social relations, and symbolic

meaning perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 30, 240–259.

*

Zellars, K. L., Hochwarter, W. A., Perrewé, P. L., Miles, A. K., & Kiewitz, C. (2001). Journal of Managerial Issues, 4, 483–499.

*

Zhou, J., & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Academy of

Management Journal, 44, 682–696.