Uploaded by

llllei63

Environmental Risk Management in China: Integration & Prioritization

advertisement

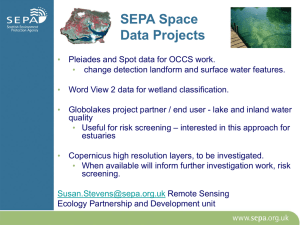

This article was downloaded by: [Wageningen UR Library] On: 11 December 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 907218144] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 3741 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Contemporary China Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713429222 Integrating and Prioritizing Environmental Risks in China's Risk Management Discourse Lei Zhang; Lijin Zhong Online publication date: 27 January 2010 To cite this Article Zhang, Lei and Zhong, Lijin(2010) 'Integrating and Prioritizing Environmental Risks in China's Risk Management Discourse', Journal of Contemporary China, 19: 63, 119 — 136 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/10670560903335835 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10670560903335835 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Journal of Contemporary China (2010), 19(63), January, 119–136 Integrating and Prioritizing Environmental Risks in China’s Risk Management Discourse Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 LEI ZHANG and LIJIN ZHONG* Human society faces a growing number of risks, including both natural disasters and risks that stem from human behavior. This is particularly true in China, which is experiencing rapid social, economic and political transitions. Since the 1970s, China’s modernization process has been accompanied by the emergence of an increasing number of man-made risks, in particular environmental pollution, but until very recently, a risk management system did not exist in China. Society was woken up by a series of disasters and accidents, including SARS in 2003, followed by the explosion of avian flu and the chemical spill in the Songhua River in 2005. The last incident in particular finally kicked off the development of a national risk management system (specifically an emergency response system) in China. This paper analyses the status quo of the legislation, institutions and mechanisms for risk management in China and identifies opportunities and strategies for prioritizing and integrating environmental and health risks into the emerging system. The study concludes that although a series of alarming incidents have succeeded in putting risk management issues at the top of the public and political agenda, currently risk management in China can be characterized as reactive and compartmentalized, with a lack of prioritization and integration of policy efforts and resources. There is also a danger that the traditional statecentered approach may fail to create an effective risk management system, which requires improved transparency, accountability, and cross-sectoral coordination. The paper concludes with the proposal of strategies that might enable the environmental authorities to be more effective and reduce their marginalization and isolation. I. Introduction: theories of risk and risk management Three decades ago, the German social theorist Ulrich Beck declared that we were ‘living on the volcano of civilization’ and that human beings had entered a risk society.1 His panoramic analysis of the condition of Western societies has already been hailed as a classic. Beck defined risk management as ‘a systematic way of dealing with hazards and insecurities induced and introduced by modernization * Lei Zhang is currently at the Environmental Policy Group in Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Lijin Zhong is in the College of Environmental Science and Engineering at Tsinghua University, China. 1. U. Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity, trans. Mark Ritter, Introduction by Scott Lash and Brian Wynne (London: SAGE Publications, 1992 [originally published in 1986]), 260 pp. ISSN 1067-0564 print/ 1469-9400 online/10/630119–18 q 2010 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/10670560903335835 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG itself’. Beck was well ahead of his time in calling attention to the importance of the concept of risk and the practice of risk management as essential features of modern society. Developments since his first work have confirmed his view, and there is little doubt that debates over how to manage risk will increase in their importance.2 In addition to uncontrollable natural catastrophes (such as hurricanes, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, where the possible loss is considered to have been caused externally)3, there is now growing recognition of risks that are generated by modernization, including environmental/ecological risks that are closely associated with human health risks, work safety issues and social unrest.4 The interconnection between human and ecosystem health is now a given: not only is it recognized on an intuitive level but its significance has also been measured in terms of its contribution to the burden of disease.5 The World Health Organization, in conjunction with the World Bank, estimates that 20% of deaths in the developing world are directly attributed to environmental factors related to pollution and states that proper environmental management is the key to avoiding the quarter of all preventable illnesses which are directly caused by environmental factors.6 Many serious public health problems have been caused by or associated with environmental pollution,7 including, most notably, the Los Angeles smog of 1943, the London smog of 1952, Japanese Minamata disease in 1953, the Bhopal gas leak disaster in 1984, the Basel warehouse fire in 1986, and the Baia Mare spill in 2000. We have begun to understand that economic development can impair public health if environmental and social considerations are marginalized.8 However, recognition in academic research of the interactions between environment and social risks and health has not been echoed in risk management practices. Although risk management is interdisciplinary in nature, in practice it is excessively compartmentalized9 and traditional risk assessment and management approaches designed to deal with the risks of an earlier time have failed to cope with the 2. See William Leiss’s review on Risk Society, Towards a New Modernity by Ulrich Beck, in the website of Canadian Journal of Sociology online, available at: http://www.ualberta.ca/,cjscopy/articles/leiss.html (accessed 20 December 2008). 3. N. Luhman, Risk, A Sociological Theory (Edison, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2005). 4. As concluded by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, available at: http://www.millenniumassess ment.org (accessed 20 December 2008). 5. R. T. Di Giulio and E. Monosson, ‘Interconnections between human and ecosystem health: opening lines of communication’, in R. T. Di Giulio and E. Monosson, eds, Interconnections Between Human and Ecosystem Health (London: Chapman and Hall, 1996), pp. 3 –6. 6. See WHO website, available at: http://www.who.int/phe/en/ (accessed 20 December 2008). 7. R. D. Gupta, Environmental Pollution, Hazards and Control (New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, 2006); Jing Fang and Gerry Bloom, ‘China’s rural health system and environment-related health risks’, Journal of Contemporary China 19(63), (2010). 8. F. Pearce and S. Tombs, ‘Hegemony, risk and governance: “social regulation” and the American chemical industry’, Economy and Society 25, (1996), pp. 428–454; M. Gandy, ‘Rethinking the ecological leviathan: environmental regulation in an age of risk’, Global Environmental Change 9, (1999), pp. 59–69; W. Leiss, Smart Regulation and Risk Management, A Paper Prepared at the Request of the Privy Council Office and External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation (Government of Canada External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation), available at: http://www. smartregulation.gc.ca; C. Hales et al., ‘Health aspects of the Millennium Impact Assessment’, Ecohealth 1, (2004), pp. 124–128; C. Butler, ‘Peering into the fog: ecologic change, human affairs, and the future’, Ecohealth 2, (2005), pp. 17– 21; P. Weinstein, ‘Human health is harmed by ecosystem degradation, but does intervention prove it? A research challenge from the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment’, Ecohealth 2, (2005), pp. 228–230. 9. A. Miller, ‘Ideology and environmental risk management’, The Environmentalist 5, (1985), pp. 21–30. 120 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 INTEGRATING AND PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS increasing complexity of risk and its changing social context.10 As Robert and Lajtha11 have pointed out, the traditional risk management framework is inadequate and a number of conceptual black holes can be identified. Traditional responses, which mainly involve policing by the state, have increasingly come to be perceived as insufficient and unsatisfactory.12 Given the widespread implications of risk management, Griffiths pointed out that, ‘it is important to strive towards the fullest possible integration of all relevant inputs’.13 The challenge of the risk society is to create political regimes and institutions capable of meeting rising public expectations for risk containment and reduction in the face of the growing pace and complexity of risk generation and the progressive intertwining of risk with deeper questions of ethics, the social ends of government, and democratic process.14 To meet this challenge, different models for risk management have been conceived and practiced in different countries. Both the European and the American initial risk management systems were responses to alarming chemical industrial accidents. Of these accidents the Bhopal gas leak disaster in 1984 led to the greatest number of human casualties, the Basel warehouse fire in 1986 caused large-scale pollution of the river Rhine, and the Baia Mare spill in 2000 severely threatened the Danube River. More recently the towns of Enschede in 2000 and Toulouse in 2001 were seriously affected by chemical explosions.15 Recognizing the importance of risk management systems for protecting human health and safeguarding the environment, the 1980s saw the first wave of legalization and institutionalization in the West, for instance, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act of 1986 in the United States. This federal law was a congressional reaction to a number of incidents, most notably the 1984 Union Carbide incident in Bhopal, India, but this law is part of a much broader set of activities, protests, pressures, and claims in many countries in the 1970s and 1980s, brought together under the right-to-know denominator. In a significant number of OECD countries, this resulted in right-to-know legislation and information disclosure provisions in the 1980s (six countries even had them installed in the 1970s). After about two decades of development, both Europe and the United States have comprehensive systems that are based on multidisciplinary understandings and that serve as models for the rest of the world. Their experiences also show that the integration of health, environment and safety management into one coordinated risk management system is both crucial and cost-effective.16 For instance, the new National Response Plan (NRP) 2004, which is built on the template of the National 10. R. E. Kasperson and J.X. Kasperson, ‘The social amplification and attenuation of risk’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 545, (1996), pp. 95 –105. 11. Robert and Lajtha, ‘A new approach to crisis management’, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 10(4), (2002), pp. 181 –91. 12. I. K. Richter et al., Risk Society and the Culture of Precaution (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006). 13. R. Griffiths, ‘Acceptability and estimation in risk management’, Science and Public Policy, (1980), pp. 154 –161. 14. Kasperson and Kasperson, ‘The social amplification and attenuation of risk’. 15. OECD, OECD Guidelines for Chemical Accident Prevention, Preparedness and Response: Guidance for Industry (Including Management and Labour), Public Authorities, Communities and other Stakeholders (Paris: OECD, 2003). 16. Ibid.; US EPA, 2004 Year in Review: Emergency Management—Prevention, Preparedness and Response (US EPA), available at: http://www.epa.gov. 121 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG Incident Management System (NIMS), is an all-discipline, all-hazards plan that establishes a single, comprehensive framework for the management of domestic incidents, the OECD Guiding Principles for Chemical Accident Prevention, Preparedness and Response (1992 first edition to 2003 second edition). Indeed, one of the common trends in these countries and regions is that environmental security is gaining in importance in overall risk management, although this has not translated into pragmatic institutional arrangements that enable the integration of environmental risk management into the system as a whole. Theoretical discussions and empirical observations highlight the fact that environmental risks are, in many cases, the causes and/or the consequences of other types of risks or incidents. Given the fact that environmental risk is an integral dimension of contemporary production processes,17 the greatest benefit of integrating environmental risks into a systems context is that it provides a framework for considering the costs and benefits of strategies for prevention and mitigation.18 For this reason, the importance of environmental risks and incidents, which are more controllable and preventable than those generated by natural processes, should be recognized and given more attention as risk management systems are established or modified. There is now a consensus that an effective risk management system should include the following elements: prevention, preparedness, response and recovery (see Figure 1). But while it is easy to understand the necessity of these four steps in risk management, it is a real challenge to weigh risks and set priorities across different risk categories, to create institutions that guarantee cross-sectoral coordination, to allocate resources effectively and to address underlying social characteristics, structures or processes.19 As we I have argued in the second paragraph above, the connection between environmental risks and other types of risks justifies the prioritization of environmental risk management in the broader system. Given the long-term impacts that environmental incidents can have on affected populations and the environment, recovery is far from an easy and one-time task, but rather one that requires different actions and involves different actors and long-term commitment as well as the investment of resources. Managing a ‘double risk society’: the China case If the distribution of ‘bads’, with globalizing ecological risks primary among them, is a dominant characteristic of the affluent ‘risk-society’,20 the mixed importance of both the fair distribution of ‘goods’ (such as wealth and social benefits) as well as the ‘bads’ (such as pollution and health damage) has made many developing countries and the ones in transition ‘double-risk’ societies.21 As a country in the midst of rapid 17. Gandy, ‘Rethinking the ecological leviathan’; Pearce and Tombs, ‘Hegemony, risk and governance’. 18. Bartell S. Dale et al., ‘Systems approach to environmental security’, Ecohealth 1, (2004), pp. 119 –123. 19. J. Salter, ‘Risk management in a disaster management context’, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 5, (1997). 20. Beck, Risk Society. 21. L. Rinkevicius, ‘The ideology of ecological modernization in “double-risk” societies: a case-study of Lithuanian environmental policy’, in G. Spaargaren, A. P. J. Mol and F. H. Buttel, eds, Environmental Sociology and Global Modernity (London: SAGE Publications, 1999). 122 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 INTEGRATING AND PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS Figure 1. Integrated risk management system prioritizing environmental risk. and extensive social, economic and political transitions, which have stirred up many deeply rooted conflicts and problems in society as development moves forward, China is a typical ‘double-risk’ society.22 Over the past three decades, China’s economic explosion has created an ecological implosion. Environmental degradation is costing the country nearly 9% of its annual GDP.23 Overdevelopment and the poor management of rivers, forests, grasslands, and land affect the livelihoods of rural and urban residents, and both rich and poor. Biodiversity is increasingly threatened, and the impact of pollution on people’s health is severe. Environmental pollution is blamed for the rise in cancer.24 The number of premature deaths in China caused by respiratory diseases related to air pollution is 750,000 a year (a more conservative estimate by SEPA is 400,000 a year).25 In addition, the environment has become one of the leading causes of rising social unrest in China. In 2004 the government recorded 74,000 mass protests and in 2005 the number of criminal cases related to public disorder was reportedly as high as 87,000. In 2005, the international and domestic media were kept busy reporting on numerous environmental protests, several of which spiraled out of control, resulting in beatings, arrests, and even deaths.26 The industrial sector contributes about half of China’s GDP but also generates serious risks for society and the environment. Despite China’s increasingly vigorous efforts to curb industrial pollution over recent decades, industry remains the principal culprit of 22. L. Zhang, Ecologizing Industrialization in Chinese Small Towns, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Wageningen University, 2002. 23. J. L. Turner and L. Zhi, ‘Chapter 9: Building a green civil society in China’, in State of the World 2006: Special Focus: China and India, available at: http://www.worldwatch.org/node/4000 (accessed 20 December 2008). 24. According to a Health Ministry survey in 30 cities and 78 counties, available at: http://planetark.org/ dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/41947/story.htm (accessed 20 December 2008). 25. China: Growth—and Growing Pains, available at: http://www.thefreelibrary.com/China:þ Growth – andþ growingþpains.-a0177072018 (accessed 20 December 2008). 26. E. Economy, ‘The lessons of Harbin’, Time Asia Magazine 166, (5 December 2005), p. 23; J. L. Turner, working paper ‘China’s environmental crisis: opening up opportunities for internal reform and international cooperation’ http://www.chinabalancesheet.org/Documents/PaperEnvironmentPaper.pdf (2006). 123 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG environmental degradation and threats to public health.27 To take the petro-chemical industry as an example: in 2004 the output of this sub-sector increased by 32.3% over 2003 and accounted for 18% of the national GDP. Demand-driven expansion of the scale of production necessarily increases the risks and the risk is heightened by the fact that most of these potential ‘bombs’ are located along major rivers and lakes and in densely populated areas. By 2006, there were 21,000 chemical plants along rivers in China and half were on either the Yangtze or Yellow Rivers, the country’s two main and most populated arteries.28 Within two and a half months of the chemical spill in the Songhua River on 13 November 2005, SEPA received 45 reports of environmental accidents, including a cadmium spill into the Beijiang River in Guangdong province.29 The question is not whether similar incidents will occur in the future, but when and where the next one will happen and what we can do to prevent and prepare for it. As a latecomer in this field, China can learn a lot from international experience. At the same time, the risks China faces are more acute than in developed countries, and China lacks the institutional capacity and social infrastructure required to cope with these risks. This implies that China has to find a more effective and affordable solution for safeguarding its modernization project. Figure 1 shows what such a solution might look like. The most important feature of this proposed solution/strategy is prioritizing environmental risks and focusing on prevention and preparedness. Given the fact that China needs to build its risk management capacity in social, economic and political contexts that differ from those in the Western world, more China-specific systems need be created to protect people and the environment there. The remainder of this article analyzes the status of current legislation, institutions and mechanisms of Chinese incident management and identifies opportunities and strategies for integrating environmental elements into the emerging system. Section II further analyzes recent developments in the Chinese system, which leads to recommendations for strengthening the system. II. Chinese risk management system in the making and its characteristics Although various man-made risks, especially ecological/environmental risks, have accompanied and been intensified by economic reform in China since the end of the 1970s, there was until recently, no risk management system in China. Effectively, the country was like a person with no immune system. China has only recently begun to respond to the increasing risks associated with its current mode of development. Arguably, two major events marked the rather short history of the Chinese risk management system (which has mostly taken the form of emergency response), namely, SARS in 2003 and the chemical spill in the Songhua River in November 2005.30 In the wake of SARS, the term ‘state of emergency’ first 27. H. Shi and L. Zhang, ‘Environmental governance of China’s rapid industrialization’, Environmental Politics 15, (2006), pp. 272–293. 28. US EPA, 2004 Year in Review. 29. SEPA, News Release on Recent Environmental Accidents, available at: http//:www.zhb.gov.cn. 30. The first city-level risk management system was started in Nanning, the capital city of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in May 2002. Shanghai was the first among provincial level governments which started to formulate its overall emergency response plan in 2001: available at: http://www.enorth.com.cn (accessed 9 January 2006). However, these local practices did not attract political and public attention at that time. 124 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 INTEGRATING AND PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS appeared in China. In fact, shortly after SARS, the modified Constitution 2004 changed the term ‘enforcement of Martial Law’ to ‘state of emergency’. This modification indicates the shift of political attention from the traditional focus on political stability to other domains, including major natural or human disasters and emergencies, and marks the beginning of legislation on public risk management. Not surprisingly, the first piece of legislation after SARS was the ‘Public Health Emergency Response Ordinance’ issued in May 2003. In September 2003, the Beijing municipal government issued its Response Plan for the Prevention and Control of SARS. In order to formulate the National Emergency Response Plan, a working group was formed in July 2003 under the leadership of the State Council. In May 2004, the State Council circulated the ‘Guidelines for Formulation of Emergency Response Plans by Provincial/Municipal Governments’ and urged local governments to report their plans to the State Council before the end of September 2004. In January 2005, Premier Wen Jiabao approved the National Emergency Response Plan, together with 25 Specific Thematic Plans and 80 Sectoral Plans. On 22–23 July 2005, the State Council called for the first National Working Conference on Public Incident Management, which marked the start of the institutionalization of public risk management in China. On 8 January 2006 when the State Council officially issued the National Emergency Response Plan, all the provinces and municipalities had completed their plans.31 In the ‘Guidelines’ of the State Council, public incidents are defined as emerging public incidents, natural or manmade, that cause major casualty, loss of property, ecological and environmental damage and social threats. These incidents are further divided into four categories: natural disasters (earthquakes, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, tropical storms, forest fires, biological disasters, etc.); catastrophic incidents associated with industrial production, traffic and transportation, public works, and environmental pollution and ecological damage; public health and medical emergencies (epidemics, food safety and other incidents that threaten public health and safety); and civil disorder (terrorist attacks, economic crises and diplomatic crises). Incidents are graded using a four scale according to their nature, severity, susceptibility to control, etc., with Grade I being the most severe (see Table 1). Obviously, this definition does not recognize the weight of environmental risks and their relationship with other risks, as we argue should be done. Consequently, the emergency response plans do not reflect a sufficient integration of environmental considerations and there is a lack of cross-sectoral coordination and cooperation in practice. Not surprisingly, after the explosion of the chemical plant, the newly formulated emergency response plans in Jilin, Heilongjiang and Harbin were found not to have been fully functioning. The first reaction from the local government after the explosion focused only on production safety, without taking into account the environmental pollution consequences and its affect on the drinking water supply, which could have been avoided or mitigated if proper measures had been taken quickly.32 Thus, this accident glaringly exposed the weaknesses within the current risk management systems in terms of the legal framework, institutional 31. ‘The establishment of Chinese incident management system’, China Youth Daily, (8 May 2006). 32. J. W. Chang, Rethinking Songhuajiang Pollution Incident: Problems in Chinese Environmental Legislation (China Institute of Law), available at: http//:www.iolaw.org.cn/. 125 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG Table 1. The classification of public risks in China Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 Risk categories of Chinese ERS Natural disaster Catastrophe incidents Public health and medical incidents Social security threats Flood/drought, hurricanes, storms, earthquake, biological disaster, wildland/forest fire, etc. Work safety, transportation accident, public infrastructure accident, environmental pollution, ecological damage, etc. Epidemic, unknown disease, food safety, animal epidemic, and other occurrences threatening public health and safety Terrorist attacks, economic crisis and diplomatic crisis, etc. capacity, and the efficacy of the response measures taken, as well as other ‘unstructured factors’ such as awareness, public participation, transparency and freedom of information. Legislation Legislation pertaining to risk management in China is a typical example of reactive law making. Although prior to 2003 China had a few relevant laws governing the enforcement of martial law, the mitigation of the consequences of earthquakes, and flood prevention and production safety, the legal framework for public incident management was fragmented and inadequate. As of 2007 existing laws dealt mainly with specific or sectoral risks, not recognizing the weight of environmental risks and the ways in which they are connected to public health and other risks. The range and severity of risks in China today calls for the creation of a more comprehensive and coordinated risk management system with a more solid legal base. This is why an emergency response law was drafted as an expedient response to SARS in 2003. The Emergency Response Law came into effect from 1 November 2007. This law is an important legal base for building a risk management system in China, although it focuses only on one of the four elements of the risk management cycle. Apart from specific laws directly addressing certain risks, there are only a few clauses within environment-related legislation that can guide and support integrated environmental risk management. For instance, the only relevant part in the Chinese Environmental Protection Law 1989, Article 31, specifies . . . in the event of the occurrence of incidents that cause or might cause pollution, the responsible organization must take control actions, inform affected organizations and citizens, and report to the local Environmental Protection Bureau and other relevant authorities. Potential polluters should take necessary measures to prevent and control pollution incidents. 126 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 INTEGRATING AND PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS But Article 31 does not give a clear definition of what an environmental incident is or make specific requirements regarding emergency responses, such as warning systems, reporting, information disclosure, impact assessment, legal responsibilities, recovery, etc. In addition, this law does not require industries to install emergency systems and does not overcome the horizontal and vertical compartmentalization of tasks and responsibilities across authorities; nor does it indicate how this law relates to other relevant legislation, such as the Epidemic Prevention and Control Law and the Work Safety Law. This ambiguity is also reflected in other laws regarding emergency responses to environmental problems, such as legislation regarding the prevention and control of water, air and solid waste pollution, various ecological damage prevention and control laws, and the environmental administrative law.33 Overall, the current legislation does not provide a sound base for the creation of a comprehensive national incident management system which recognizes the importance of environmental risk prevention and control and justifies the integration of environmental risks into other sectors. The current emergency management system focuses only on responses to the disasters that have already occurred, which is only one of the elements in a complete and effective risk management system that includes prevention, preparedness, response and recovery. It is too early to say how the emergency response law will overcome these weaknesses in the legal system and how environmental risk can be fully integrated into other emergency response plans. Furthermore, the effective implementation of emergency response plans requires legally-mandated and institutionalized freedom of information and, community rightto-know measures. It must also address issues of compensation, liability and responsibility for organizing recovery after incidents, many of which are not yet on the agenda of the Chinese legislators.34 Although the Environmental Information Disclosure Decree took effect on 1 May 2008, a survey we have conducted on its implementation concludes that it is seen by the majority of EPBs as a burden, and that only lip service is paid to information disclosure.35 Institutional building Arguably, a formal institutional network for comprehensive emergency management did not exist in China before SARS. An ad hoc National Emergency Response Office within the State Council was quickly established as a liaison point between the State Council and other governmental authorities in 2006 after the Songhua River pollution incident.36 This Office organizes resources for the formulation of the National Emergency Response Plan, approves other specific thematic emergency response plans, and guides the practices of other ministries and local 33. J. W. Chang, Problems and Countermeasures Regarding Legislation for Environmental Incident Management in China, available at: http//:www.h20-china.com. 34. J. W. Chang, Foreign Experience in Environmental Legislation of Public Participation and Lessons for China (China Institute of Law), available at: http//:www.iolaw.org.cn. 35. L. Zhang, A. P. J. Mol and G. Z. He, unpublished working paper ‘Environmental governance and information disclosure in China’, submitted to Environmental Science & Technology. 36. See ‘Circular regarding the establishment of State Council Emergency Response Office’, Policy Paper No. 32 by the General Office of State Council, 10 April 2006. 127 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG governments.37 It is also responsible for coordination among different organizations and mobilizing the resources needed in case of emergency. Given its current capacity and authority, it is doubtful that this Office can influence the legislative bodies and other governmental authorities in terms of institutional building and legislation. In order to build up a nationwide institutional network, the State Council has urged its ministries and departments to set up their own offices to be responsible for the formulation and implementation of their emergency response plans. This has led to increases of staff, budgets, and training in these organizations.38 Governments at various levels are responsible for incident management work following the practices at the national level (Figure 2). Outside government, enterprises and organizations are also required to make their own emergency response plans. However, nothing is said about the contents of these plans or how they will be monitored. Cities have been creative in designing and developing their own risk management systems. Four different models have emerged so far, represented by Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Nanning. Each model presents a different kind of leadership, reflecting an emphasis on different risks and different agencies. Beijing and Nanning have created an overarching commission or center, while Shanghai and Guangzhou have built onto existing departments. These models set examples for other cities to be innovative in creating their institutional arrangements to fit their own situations (Table 2). It is noted that in all four of these models, environmental risk and its integration with other risk management is generally neglected. Given the past record of rather unsuccessful attempts to integrate environmental concerns into the scope of work of other sectoral departments in China, SEPA is challenged by the question of how to enable environmental elements to penetrate other plans. This partly explains why in the National Environmental Emergency Response Plan (one of the theme-based plans), certain responsibilities, such as coordination among different authorities, implementation of environmental emergency responses, the establishment of an early warning system for environmental incidents, formulation of the National Environmental Emergency Response Plan, public awareness raising and the official release of information, are left to the National Inter-Ministerial Conference for Environmental Protection (NIMCEP). But the NIMCEP, which was convened in 2001 by the State Council for Inter-Ministerial Coordination on Environmental Issues39 is a body that only meets occasionally to respond to specific events, and it is based on loose networks. Although it facilitates the exchange of information about environmental problems across sectors, the NIMCEP’s decisions have no legitimacy. In this situation, it is far from clear how SEPA and its local counterparts can play a strong role in the emerging risk management systems in China. 37. At the time of writing, 80 sectoral emergency response plans and 25 subject-based emergency response plans had been formulated. The National Emergency Response Plan for Environmental Incidents is one of the subject-based plans issued by the State Council. General Office of the State Council, ‘Emergency Response System Framed’, 5 August, 2006, at: http://www1.www.gov.cn/ztzl/content355022.htm. 38. For instance, the State Work Safety Supervision Administration (SWSSA) planned to add 80 staff in its Emergency Response Headquarters, which was established in January 2006. During the 11th ‘Five Year Plan’ of the SWSSA, 20.3 billion Yuan will be allocated to establish its vertical emergency response system, including six regional relief stations, 11 sectoral aid systems, 31 provincial headquarters and 333 municipal branches. See New Beijing Daily, (13 March 2006), available at: http://www.sina.com.cn. 39. SEPA, Major Events of Environmental Protection 2002, available at: http//:www.sepa.gov.cn. 128 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 INTEGRATING AND PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS Figure 2. Four-level emergency response system in China. Measures and actions The central government’s call for risk management has been received by different departments in different ways. New measures and actions have been taken to raise awareness, to improve the information of freedom, to build institutional capacity, to institutionalize public participation, and so on. It is good to see that communicating with the media during emergencies was a topic in the training of the relevant official spokesmen/spokeswomen in workshops recently organized by the Information Office of the State Council.40 The State Work Safety Bureau has launched a training project for emergency response at the central and local levels for governmental officials, responsible managers of industries and organizations.41 Although this is the most systematic training project on this issue so far, the bulk of the training material focuses on work safety and public health. The management of environmental incidents is mentioned only briefly and none of the trainers is an environmental expert. To a large extent, the increase in environmental pollution accidents in recent years is the result of limited monitoring capacity and the lax enforcement of environmental regulations. Campaign-style reactive responses may succeed in attracting attention from the media and the public, as well as support from local governments for a short time, but the effects are often short-lived and there is rarely adequate follow-up. During a national telephone working meeting on responses to environmental incidents on 1 December 2005, SEPA required other EPBs to increase their awareness and capacity for emergency responses, to focus on prevention through 40. According to a speech by Cai Wu, the director of the Information Office of State Council, available at: http:// www.enorth.com.cn (accessed 3 December 2005). 41. State Administration of Work Safety (2006). 129 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 Table 2. Four models of city emergency response systems in China City Leadership Executive institution Characteristics Beijing Beijing Public Emergency Response Commission Beijing Emergency Response Headquarters in the General Office of the Beijing Municipality Shanghai Shanghai Disaster Mitigation Leading Team Guangzhou Guangzhou Social Jointaction Service Team Nanning Nanning City Emergency Response Center, a governmental agency reporting directly to the Nanning Government Shanghai Emergency Response Center in the Shanghai Public Security Bureau plus operating arms based in different relevant departments Guangzhou Social Jointaction Center in the Guangzhou Public Security Bureau Nanning City Emergency Response Center Coordinate cross-sectoral interests and responsibilities via commission and stress the status of Beijing as the capital city Small headquarters and big network based on existing facilities and resources Rely on the existing capacity of the Public Security Bureau Creation of a new hightechnology-based center for emergency response more publicity activities and to establish effective systems for reporting incidents. SEPA also specified the procedure for reporting incidents within the EPB system in March 2006,42 but it is not enough to raise risk awareness and capacity only within the SEPA (the Ministry of Environment since March 2008) system. It is more important to make environmental responsibility part of decision making in other departments. In recent years there has been an increase in the number of investigations and disciplinary actions taken against officials and government personnel responsible for wrong doing. In 2005, 17 officials were found by SEPA to be responsible for nine incidents. During a recent meeting of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, the newly appointed environmental minister, Mr Zhou Shengxian, called for local governments to give more protection and support to local environmental officers.43 The new minister expressed his intent to change the situation in which the directors of local EPBs are forced to choose between local economic interests on the one side, and the enforcement of environmental regulations on the other. However, it is not yet clear how he can make government officials pay for their environmentally damaging behavior.44 The problem is fundamentally the same when it comes to making local officials responsible for environmental risk management. 42. SEPA, ‘Circular on “Environmental incidents reporting measures” (trial)’, SEPA Policy Paper 59, (2006). 43. ‘Will public participation help environmental protection?’, China Daily, (22 May 2006). 44. ‘Protect the EPB directors’, People’s Daily, (22 May 2006). 130 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 INTEGRATING AND PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS In general, public information and participation in risk management are still limited. Governmental and market failures mean that it is essential for the public to be involved in environmental governance, including environmental risk management. A strong trend towards greater openness on environmental problems can be observed in the wake of the various incidents that have occurred in recent years. To open the political space for public participation in environmental governance and risk management, the Chinese government has finally started to take substantial actions rather than merely paying lip service to public participation. The recent decision of the State Council on ‘The Scientific Development Outlook and Enhancing Environmental Protection’ stresses that ‘ . . . developmental plans and construction projects must be decided on the basis of sufficient public participation and under public supervision by conducting public hearings or public announcements’. SEPA is actively responding to this call and is now working on ‘Measures Regarding Public Participation in Environmental Protection (trial)’ as an attempt to institutionalize public participation and to help SEPA conduct its work. This will be the first document to specify detailed procedures for public participation on environmental issues.45 SEPA was the first agency in China to issue regulations and actually hold public hearings based on the new Administration Permission Law passed in July 2004,46 and the Environmental Information Disclosure Decree 2007 was the first effort by a particular sector to operationalize the general regulations on Open Governmental Information. Although the government remains wary of too much citizen activism, China’s top leaders recognize that government needs help to address a broad range of emerging social and environmental ills and to keep local governments in check, especially in light of the downsizing of the central government and the growing power of the local governments. Chinese environmental NGOs were the first to register as social organizations and now form the largest sector of civil society groups in China (nearly 2,000 in number).47 Inadequate technical capacity and support is another problem. Apart from the participation of the public and NGOs, the formation of subject-specific expert team is an integral part of an emergency response plan. Decision making in responding to emergencies must be based on scientific evidence. While it is easier for the central government to access and mobilize expertise when incidents occur, it can be impossible to obtain this technical support at the local level. Therefore, it is necessary to establish an information-sharing mechanism to maximize the benefit of expert resources. In addition, as part of institutional capacity building, expert teams need be formed to provide various kinds of technical support. As a preparedness measure, research that can inform how to respond in case of incidents should be promoted for chemicals that are produced on a large scale. Internet-based websites can play an important role in information and knowledge sharing, for example, the Longgang Information Net for Emergencies.48 Along with the formulation of emergency 45. Ibid. 46. Administration Permission Law requires administrative agencies to inform citizens of their right to express their opinions at public hearings regarding any government project that impacts them (Tang et al., 2005); Turner, ‘China’s environmental crisis’. 47. Turner, ‘China’s environmental crisis’. 48. See http://www.ics.lg.gov.cn/default.asp. 131 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG response plans, some governments or organizations have conducted various exercises simulating emergencies.49 All these activities, including awareness raising, training, the creation of new offices, recruitment of new staff and experts, the installation of monitoring systems and information systems, research on technical responses, and recovery measures, require capital, material and human inputs. For instance, Nanning Municipality has invested 170 million RMB for the construction of an emergency response system including a headquarters and five extended bases which cover an area of 10,029 square kilometers. This high-tech system follows the American 911 system, and was built with technical cooperation with Motorola. It is not difficult to calculate the investment that would be required if the whole of China were to choose a similar system.50 China’s risk management system has to compete for resources with other urgent needs. The newly issued Guideline for the 11th Five Year Plan devoted one chapter to risk management and hopefully this will lead to increased investment in this field as investment now will prevent greater losses in the future. Given the limited resources in China, it is extremely important to assess the weight of different risks and to identify priorities. Focus should be put on preventive measures to avoid the huge cost of response and recovery afterwards. For example, China has earmarked 26.6 billion RMB (US$3.3bln) to make water from the poisoned Songhua River drinkable by 2010.51 This expense could have been saved if a more effective response plan could have been implemented immediately after the explosion. Obviously, this is a formidable task for China and international assistance is badly needed. On the one hand, as a latecomer, China should take the opportunity to learn from other countries in developing its risk management system. International cooperation can also help China reduce investment in R&D activities, avoid repeating the same mistakes, and improve communication during transboundary disputes. III. Strategies for risk management integrating and prioritizing environmental risk Judging from current developments in China regarding risk management, it is fair to say that the newly emerged risk management system is a kind of ‘quick and dirty’ reaction on the part of the Chinese government, which focuses only on responding to emergencies. The Songhuajiang incident should not be merely viewed as exposing the shortcomings in the emergency preparedness of industry. It also exemplified the institutional weaknesses that underlie nearly all environmental and risk management problems in China—local government protectionism, insufficient government transparency, weak and understaffed environmental enforcement agencies,52 49. SEPA, Announcement on Observing Environmental Emergency Response Rehearse, available at: http//:www.zhb.gov.cn; ‘SEPA switches on its Environmental Emergency Response Plan in Huai River Basin’, People’s Daily, (30 April 2005); ‘Xie Zhenhua says: environmental indicators for performance evaluation of government officials’, Xinhuanet, (18 November 2005). 50. Nanning City Emergency Response Center: The First in China, available at: http://www.nanning.gov.cn/ (accessed 9 August 2004). 51. ‘China has earmarked 26.6 billion yuan to make water from its Songhua River drinkable’, Beijing Youth Daily, (8 January 2006). 52. SEPA has just fewer than 300 staff. 132 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 INTEGRATING AND PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS compartmentalized policy efforts, the absence of a coordinated legal framework, and a pervasive lack of mechanisms for informing and involving the public in environmental protection and risk management.53 Although issues like public participation and freedom of information are stressed when it comes to risk management, the actual legal and institutional structures in place are not really different from the traditional add-on solutions. They do not address the reality of what a disaster is: a wake-up call signaling that without real reform, there is the risk of hundreds of millions of citizens becoming desperately ill citizens, greater social unrest and, perhaps even the end of the Chinese economic miracle.54 Finally, there is no clear strategy regarding risk management in China today that is designed to achieve cost-effectiveness and safeguard economic development by prioritizing environmental risks and following preventive principles. In this rather gloomy picture one hopeful sign is that during the NPC and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) in March 2006, the issue of public incidents management, especially environmental security, was in the political spotlight. Both the NCP representatives and CPPCC members raised bills that emphasized the strategic significance of environmental security, including calls for an all-in-one coordination institution for national security that would stress environmental security, the further empowerment of SEPA in enforcement and enhancing vertical and horizontal co-ordinations, legislation for environmental emergency responses and so on.55 Although not yet law, these calls for action indicate an active institutional dialogue on the integration of risk management and the prioritization of environmental security. As part of the institutional reform package approved by the 11th NPC in March 2008, SEPA was upgraded to the status of Ministry of Environment Protection. This shows that the top policy makers are fully aware of the importance of environmental security and its relationship with other sectors. Of course, translating this political will into actual political and institutional reforms at the local levels is not something that will take place automatically. Nevertheless, this seemingly chaotic situation opens opportunities for reshaping environmental governance and risk management in favor of the ministry and its mission. Indeed, the new head of the MEP picked up this political signal in no time. The ‘Scientific development outlook’ might sound like an empty slogan, but China’s environmental chief Zhou Shengxian said that the slogan ‘has equipped me with a very powerful weapon. If I use this weapon properly I will not end up resigning’. Zhou also said the growth at any cost approach was changing.56 Wisely riding on the wave of the Songhuajiang incident, SEPA included in its work plan for 2006 a list of tasks that included improving enforcement of environmental regulations, building up early warning systems and emergency response plans, implementing measures for reporting environmental incidents, and monitoring potential key polluters. To this end, SEPA had been focusing on the enforcement of EIA, total pollution load control, 53. Turner, ‘China’s environmental crisis’. 54. Economy, ‘The lessons of Harbin’. 55. ‘Environment as the hot issue during NPC and CPPCC’, China Environmental News, (7 March 2006). 56. Lindsay Beck, China Warns of Disaster if Pollution not Curbed, available at: http://www.planetark.org/ dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/35596/story.htm (accessed 13 March 2006). 133 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG investigating and disciplining officials and promoting public participation and international cooperations in this field.57 However, given the nature of environmental risk and its connectedness with other risks, it is not possible for SEPA to address environmental problems and risk management issues without delegating the tasks to and involving other departments and actors. Therefore, SEPA should adjust its position in China’s risk management from an isolated sector to an embedded element in other risk management systems. Otherwise, SEPA’s efforts to improve its own response will have limited effect and SEPA will be kept busy running after incidents caused by the problems rooted in other fields, and will find itself responsible for clean-up, while at the same time being blamed for an inadequate response, just as it was in the Songhua River case. In order to improve its position in the overall risk management system and reduce its isolation, SEPA can focus strategically on three actions: lobbying for an improved legal framework for integrated risk management; institutionalizing public participation; and formulating a plan for both internal and external communications. The modified Constitution 2004 laid a good base for other law making pertaining to risk management in general. However, only if the strategic position of environmental protection and environmental risk management is recognized in the law on emergency responses will it be possible to integrate various incident response plans into one system for maximum effectiveness. In addition, the current Environmental Protection Law needs to be modified to respond to the growing environmental risks along with the rapid industrialization process. Only with this legal framework in place will it be possible to integrate environmental education, the environmental responsibilities of the various levels of governments, freedom of information, and public participation in environmental impact assessment for development planning and projects. Accordingly, all the other specific environmental laws should include incident management as an integral component. Since environmental accidents also involve environmental security assessment, the declaration of a state of emergency and, in some cases, the mobilization of military forces and diplomatic communication, it is also necessary to make a law for environmental incident responses that is approved by the Standing Committee of the NPC or an ordinance by the State Council.58 Given these considerations, MEP should take this opportunity to present a more integrated proposal to law makers so that environmental protection becomes, by law, a responsibility of all the other departments. Then the MEP and local EPBs would be able to concentrate on enforcing the regulations and supervising the performance of other agencies. One of the common features of environmental protection legislation around the world is the principle that environmental protection should be based on public participation and the public’s right to know.59 Although this is also one of the principles of Chinese environmental law, it has never been clearly defined or institutionalized. Public participation is not yet recognized as a basic human right 57. ‘Guiding principles for environmental protection in China’, China Environmental News, (16 February 2006); SEPA, ‘Circular on “Key points of National Protection Work Plan 2006”’, SEPA Policy Paper 8, (2006). 58. Chang, Problems and Countermeasures. 59. Chang, Foreign Experience in Environmental Legislation; Environmental Law Network International, International Environmental Impact Assessment (Bingen: ELNI, 1997). 134 Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 INTEGRATING AND PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS in either the Constitution or the Environmental Protection Law and the public (whether as individuals or social organizations) is often absent from environmental governance. MEP should continue to raise its voice in support of greater public participation by working closely with mass media, NGOs and environmental activists. This strategy will also help MEP with environmental monitoring and supervision. Enhancing public participation should not dilute the responsibility of the government in incident management in China. On the contrary, the increasing frequency of incidents in China challenges deep-rooted administrative traditions, attitudes and approaches, and highlights the need for more transparency and reliability. To respond to this, a series of new measures have recently been issued to guarantee collective decision making for major public projects, an expert support system, public hearings and announcements, the release of information and investigations into the parties responsible. MEP is also working on new measures to enforce public participation in Environmental Impact Assessments of public plans. Environmental indicators will be included in the evaluation of officials’ work performance as initially proposed by the former environmental minister, Mr Xie Zhenhua.60 In fact, MEP has already modified the criteria to qualify as an ‘Environmental Protection Demonstration City’ by adding an indicator for the capacity to respond to environmental incidents in April 2006, which will have veto status in the evaluation process.61 These are very positive and timely moves. Communication is an important instrument an organization can use to achieve its goals but communication plans are often neglected by Chinese organizations when a policy or a project is implemented. If MEP adopts a strategy of promoting an integrated risk management system, then the next steps should be: (a) analysis of the issues; (b) outlining the role of communications; (c) identifying target groups; (d) determining communication targets; (e) determining the communications strategy/messages; (f) determining the means; (g) budget; (h) organization; (i) implementing; and (j) evaluation. A number of methods of communication can be employed to achieve a specific objective, for instance, regular opinion and attitude surveys, mass media content analysis, ongoing networking with NGOs, interest groups and scientific institutions, and regular briefings and interviews and meetings with interest groups and the press, participating in various trainings on risk management, etc. It would also be useful to further formalize the existing National Inter-Ministerial Conference for Environmental Protection and to bring environmental security issues into its discussions. Combining the force of the ‘auditing storm’62 and the ‘environmental storm’63 can also enable MEP to make a bigger impact with fewer resources. Chinese risk management is in its infancy. Much remains to be done but the field has the potential to make a strong contribution, and win positive recognition. MEP 60. ‘Xie Zhenhua says’, Xinhuanet. 61. SEPA, ‘Circular on “Environmental incidents reporting measures” (trial)’. 62. 2004 witnessed the shocking impact of the auditing reports published by the China National Office of the Auditor on sensitive issues like corruption among governmental officials, misuse of governmental budgets, etc. Many high ranking officials fell during this ‘auditing storm’. See: http://www.xinhuanet.com (accessed 28 December 2004). 63. In 2005, more than 30 large-scale construction projects were stopped by SEPA because they failed to carry out Environmental Impact Assessment. Henceforth, SEPA increased its scrutiny of major potential polluters. These actions are labeled as ‘environmental storm’. See: http://www.xinhuanet.com (accessed 28 September 2005). 135 LEI ZHANG AND LIJIN ZHONG should take this opportunity to push the central government for real reforms which can support development based on scientific approaches. Downloaded By: [Wageningen UR Library] At: 09:31 11 December 2010 IV. Conclusions As Rob Swart predicted more than ten years ago,64 the ‘environment-related security risks associated with “conventional development” have not only increased but it will be years before we have full knowledge of their impact on social, economic, political, and institutional conditions and their environmental consequences’. Environmental factors are very important in addition to political, social and economic factors in bringing about civil strife and vital damage to the public. Time is not on China’s side to protect its people from the risks associated with modernization. Even if the lack of institutional preparation for the sudden and unexpected outbreak of SARS was tolerable and the subsequent mitigation measures were respectable, the chemical spill in the Songhua River made it extremely clear that the country needs to establish institutions and mechanisms for contingency responses to emergencies and the effective implementation of those plans. An effective risk management system is important not only in order to respond quickly to incidents, but more importantly to prevent incidents from happening. The absence of government strategies to prevent and respond to risks is now recognized and efforts have been made to change this situation,65 but although the rapid formulation of emergency response plans in China is a good sign, it must not be the end of the story. Concrete actions need to be taken to establish a national information platform for emergencies, make training and publicity plans, invest in research and development and form subject-specific expert teams. Beyond all this, awareness of and responsibility for environmental risks must be not only felt but also borne by the whole society. Increasing attention to environmental security has opened up new space for MEP and EPBs to operate. Since the current evidence does not support the creation of an integrated risk management system in China, it is wise for the ministry to take appropriate actions to bring a new order to the chaos. The new ministry should take all opportunities to systematically highlight and support nascent Chinese policy efforts to introduce integrated risk management. It can also build confidence and help to foster positive and constructive interagency interactions by facilitating cooperation across lines of tension. Given the recent nature of China’s efforts to establish a risk management system, it is clear that many questions remain, especially at the operational level, and that further research will be needed as the system evolves. This paper represents only an initial attempt to identify strategies that the Ministry of Environment might employ to further the development of an effective and integrated risk management system that prioritizes environmental protection. 64. Rob Swart ‘Security risks of global environmental changes’, Global Environmental Change 6(3), (1996), pp. 187 –92. 65. SARS and Public Policy Project Team, Governmental Emergency Response Capacity Building—Thoughts on SARS Crisis (Public Policy Research Center of Northeastern Finance and Economics University, 2003). 136