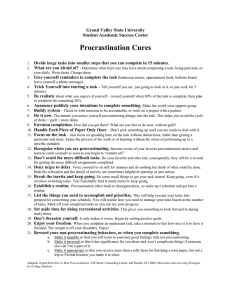

A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even if You Flunked Algebra) by Barbara Oakley Chapter Two: Easy Does It • Prime Your Mental Pump: Take a “picture walk” through the chapter before you read, glancing through graphics, diagrams, photos, section headings, summary, and questions at the end of the chapter. You will be creating neural hooks to hang your thinking on, making it easier to grasp the concepts. Reading through practice quizzes/sample problems before engaging with the material can have the same effect. • Be prepared to be stumped and confused by new concepts and problems. • Learning math and science requires both focused mode thinking and diffuse mode thinking. Focused mode is direct, rational, sequential, and analytical. Diffuse mode is associated with “big picture” perspectives, and happens when you relax and let your mind wander. If you are trying to understand or figure out something new, turn off your focused thinking and turn on your diffuse mode. Try to toggle back and forth between modes, especially if you find yourself stuck. • When you procrastinate, you are leaving yourself only enough time to do superficial focused learning. You are also increasing your stress level. The resulting neural patterns will be faint and fragmented, and will quickly disappear. Cramming at the last minute will not leave you enough time for learning, and will prevent you from synthesizing the connections. o If you find yourself procrastinating, insulate yourself from interruptions (e.g. turn off your phone) and set a time for 25 minutes. Focus on a work task – any task. Do not worry about finishing it; just worry about focusing for 25 minutes. When 25 minutes is up, reward yourself. o Imagine that at the end of the day, you are reflecting on the one most important task you accomplished that day. What would it be? Write it down. Then work on it. Try to complete at least three 25-minute sessions that day, on whatever task you think is most important. At the end of the day, reflect on what you accomplished, and think about what you will accomplish the next day. The early preparation will help your diffuse mode begin to think about how you will get tasks done the next day. Chapter Three: Learning is Creating: • Keep work sessions short to use diffuse mode after focused mode sessions. • Some diffuse mode activities are more recommended than others: o Recommended: Exercise, take a drive, draw or paint, take a bath or shower, listen to music without words, play songs you know well on a musical instrument, meditate or pray, sleep o Use briefly/sporadically: Video games, surf the web, talk to friends, help another with a simple task, read a relaxing book, text friends, go to a movie or play, watch television • Blink or close your eyes for a few second to refresh and renew consciousness and perspective • • • • • • When you find yourself becoming frustrated at something or someone, take a mental step back and observe your reaction. Frustration is a sign that you need to take a break. When you are stuck on a problem or having a difficult time learning a concept, try the following: o Ask for a different perspective. Talk to classmates, TAs, or the instructor, and ask them if they can rephrase the information in a different way. o Work on the problem or study the concept for a few minutes. Then move on to another problem or concept. Return to the first problem later. o Take a power nap. Set your alarm for 20 minutes. Darken the room, focus on slowing down your breathing, and repeat a short phrase (e.g. “time for sleep”) in your head. ! If you go over material right before taking a nap or going to sleep for the night, you have an increased chance of dreaming about it. Deciding that you want to dream about it seems to improve your chances even further. Dreaming about the material can help consolidate your memories into easily grasped chunks. To help aid in long-term memory, engage in spaced repetition – repeat what you are trying to retain over a number of days. If you are tired, it is often best to go to sleep and get up earlier the next day. When you take a short break after studying, try to recall the main ideas of what you just learned while moving around. Make sure to develop an action plan for reviewing new concepts within 2-3 days of learning them so that you do not let too many days pass without review. Chapter Four: Chunking and Avoiding Illusions of Competence • Creating conceptual chunks: mental leaps that unite separate bits of information through meaning • Attempt to recall the material you are trying to learn, rather than just rereading. Rereading and recognizing gives you illusions of competence. The only time rereading text seems to be effective is if you let time pass between rereadings so that you are engaging in spaced repetitions. • Try to recall the material when you are outside your usual place of study to help you strengthen your grasp of the material by viewing it from a different perspective. • Practice interleaving: doing a mixture of different kinds of problems requiring different strategies. Once you feel that you know a concept, try to recall or practice it in different ways, not just in the way you learned it. At the very least, try to practice/recall material in a different order every time. • Avoid long study sessions in favor of multiple, shorter sessions. If you prefer long study sessions, do not devote too much time to any one skill or concept – make sure to mix it up. • When possible, write out ideas by hand, rather than typing. • When checking answers, do not simply move on if you got the answer correct. Ask yourself how you would know how to do this problem if it were mixed with other • content on an exam? How would you know the answer if the question were phrased in a different way? Try to explain what you are learning to someone not taking your course/not familiar with the material. Simplifying material so others can learn it will be helpful in cementing your own understanding. Chapters Five and Six: Preventing Procrastination • Think of procrastination as a bad habit that you can change. Do not think of yourself as a procrastinator • Procrastination offers temporary relief from things that make us feel uncomfortable. However, the more you practice a content area, the less uncomfortable you will feel. • Recognize what launches you into procrastination mode. Cues often include: location, time, how you feel, reactions to other people, or something that just happened. o Start to develop a routine that protects you from being vulnerable to immediate cues to procrastinate. For example, studying at particular set times, shutting off your cell phone, closing tabs that are not directly related to what you are studying. o Think of your most troublesome cue and practice reacting differently to just that one cue. • Develop a ritual to precede studying, such as getting your favorite drink and sitting in a particular chair. • Figure out why you are procrastinating and see if you can substitute something else that will provide that same feeling for you. • Use mental contrasting: think about where you are now and contrast it with what you want to achieve. When you want to procrastinate, draw upon images that remind you of where you want to be, and picture yourself emerging from where you are now to where you want to be. • If you really want to check your email or Facebook, set a timer for 10 minutes. If you can get 10 minutes of focused work done, reward yourself by doing what you want to do. • Make a list of specific actions you can take to curb habits of procrastination. • Use the “Pomodoro” technique: Set a timer for 25 minutes and work without interruption, no matter what. Use this technique to train yourself to ignore distractions. Focus on process (best effort for a short period), rather than product (end result). • When it comes to multitasking, remember that constant shifting of your attention means that new ideas do not have time to take root and flourish. Each tiny shift back and forth siphons off energy. • The next time you feel an urge to check social media (or any other kind of distraction), pause and examine the feeling. Acknowledge it, then ignore it. • If you are feeling fuzzy as you are trying to look away and recall a key idea, or you find yourself rereading the same paragraphs over and over again, try doing a few jumping jacks or pushups, and then try to recall again. Chapter Eight: Tools, Tips, and Tricks • Have a saying to get started, such as, “Quit wasting time and just get on with it. Once you get going, you’ll feel better.” • Three step positive approach to procrastination: 1) No computer time during procrastination – it is too engrossing. 2) Before procrastinating, identify the easiest task you need to do. 3) Copy the information needed to work on this task onto a small piece of paper and carry it around until you are ready to get back to work. • Think of working on procrastination as self-experimentation: keep notes on when you don’t complete what you intended to, what your cues are, and what your reactions to these cues are. • Write a list of key tasks you can reasonably work on or accomplish the evening before, which helps your subconscious figure out how to accomplish them while you sleep. Keep your list to 5-10 items, and do not add to the daily list unless something urgent arises. Do the most important and most disliked jobs first. • Plan your quitting time, as well as your working time. If you find yourself consistently working beyond your quitting time, it is a sign you need to reassess your items, schedule, and/or procrastination. • Transform distant deadlines into daily ones by translating large tasks into very small ones that show up on your daily to-do lists. Chapters Ten & Eleven: Enhancing Your Memory • Use your natural visuospatial memorization abilities to build more neural hooks for the information. Create images to help you remember concepts and link these images to smells, feelings, tastes, and sounds whenever you can. • Use the memory palace technique: Call to mind a familiar place, such as the layout of your home, and use it as a visual notepad where you can deposit concept-images that you want to remember. Walk through your memory palace and deposit your images. • Make up lyrics set to the music your favorite songs to help you remember lists. Using motions along with the songs can help cement the ideas in your memory. • Pretend you are the concept you are trying to remember. Imagine your pathway and what it feels like to take that pathway. • Write out concepts you are trying to remember by hand, which will help you more deeply encode what you are trying to learn. If you are struggling to remember information that you are typing, try switching to writing out the information by hand to see if it helps. • Briefly repeat what you want to remember for a few minutes every day for several days. Gradually extend the time between practicing repetitions. • Create stories with the information where there is a plot, characters, and overall purpose. • Research has shown that regular exercise will boost your memory. • Think like an actor: Actors tend to memorize scripts by understanding characters’ needs and motivations, rather than starting by memorizing lines verbatim. Try to understand the concepts before you try rote memorization. Chapter Seventeen: Test Taking • When you get a test, start first with the hardest problem. Steel yourself to pull away within the first minute or two if you get stuck or get a sense that you might not be on the right track. Turn to an easy problem, and then go back to a harder problem. You will often find that when you return to harder problems, the next steps will seem easier to you. This hard-start-jump-to-easy process allows different parts of the brain to work simultaneously on different thoughts. Make sure you have the self-discipline to pull yourself off of a problem once you find yourself stuck for a minute or two. • Interpret symptoms such as a racing heart or a knot in the pit of your stomach as “this test has gotten me excited to do my best!” rather than “this test has made me afraid.” • When experiencing physical symptoms of anxiety, try to momentarily turn your attention to your breathing. Relax your stomach, place your hand on it, and slowly draw a deep breath. Practice this breathing technique as part of your studying. • When checking answers, try to think from a different perspective or process to avoid making the same mistake the second time around. Even checking answers out of order can help give you brain a fresh framework. • Briefly writing about thoughts and feelings about an upcoming test immediately before you take the test can lesson the negative impact of pressure on performance. Writing helps release the thoughts so they do not pop up and distract you in the heat of the moment (Sian Beilock, author of Choke: What the Secrets of the Brain Reveal about Getting It Right When You Have To). Other suggestions from Beilock include: o Test yourself in a stress-induced manner as you learn the material o Practice combating negative thoughts as they arise by cutting them off midsentence o Learn to pause for a few seconds before jumping in to solving a problem to really think about what the question is asking o Understand that a little stress help you perform at your best when it matters most. Book Notes is a series compiled by Lisa Medoff, PhD, Stanford School of Medicine’s Learning Specialist. These handouts are intended to provide at-a-glance suggestions and strategies relevant to the needs of medical students. If you find the handouts helpful, I encourage you to read the original books, as they will offer much more detailed information on the topic of interest. Please contact lmedoff@stanford.edu if you have a suggestion for a book that should be added to the series and/or if you are a student at the School of Medicine who would like to discuss in person how to implement any of the suggestions listed above.