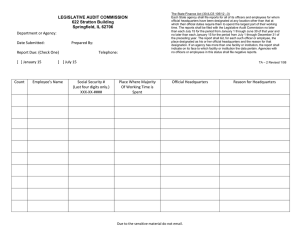

Pergamon PII: European Management Journal Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 83–91, 2001 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved Printed in Great Britain S0263-2373(00)00073-6 0263-2373/01 $20.00 Redesigning the Corporate Centre MICHAEL GOOLD, Ashridge Strategic Management Centre, UK DAVID PETTIFER, PricewaterhouseCoopers DAVID YOUNG, Ashridge Strategic Management Centre, UK The authors report the results of a recent large study of corporate centre transformation: a question which is often an early priority when a new chief executive takes office. This article summarises their approach to corporate centre design which maximises value creation. Recognising that there are differences in the pattern of headquarters between countries, the authors base their recommendation for a corporate centre design process on three different rôles played by headquarter staff: mimimum corporate parent rôle, value-added parenting rôle, and shared services rôle. A case study of Burmah Castrol is described as an example of the method 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved Keywords: Strategy Corporate headquarters, a fresh statement about the essential mission and responsibilities of the corporate centre. Sometimes these efforts lead to radical change and a new and more effectively implemented corporate strategy. More often, unfortunately, they have less success. They result in changes that are only cosmetic or temporary, with little lasting impact. Or else they cause real change, but end up by damaging corporate performance and internal relationships, not improving them. What is more, proposed changes to the corporate centre are liable to meet entrenched opposition from managers who fear they will lose out. They defend the status quo strenuously and find a whole variety of reasons for not changing. Corporate centre re-designs are easy to set up, but much harder to bring to a satisfactory completion. Parenting, When new chief executives take office, one of their early priorities is often to reassess the rôle and composition of the corporate centre. They know that the corporate headquarters represents a significant overhead, and may well be looking for ways to make it more cost effective. They are frequently embarking on new corporate strategy directions, and may be concerned about whether the corporate staff is appropriate to support them. They face probing questions from investors and analysts about spin-off and demerger options and the justification for the group, and so need a clear added-value rationale for the existence of the corporate centre. All of these concerns may be made more urgent by rumbling discontent in the business divisions about the excessive cost and influence, or the downright ineffectiveness, of corporate centre departments. For all these reasons, corporate centre re-design is frequently high on the chief executive’s agenda. Project teams are set up to examine every corporate centre function and process, targets for cost reduction and downsizing are established, and work begins on European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 A major problem is that straightforward benchmarking against other companies is not likely to provide much help, since the corporate centres of successful companies do not follow any single model. Some companies have large staffs, which they believe are more than justified by their value to the company. Companies such as Lucent or Unilever, with large corporate functions in areas such as R&D, Human Resources and IT, have staffs of several thousand. Other companies are convinced that lean headquarters are the right answer. For example, Tyco International, Nucor, and Virgin all have fewer than 50 corporate centre staff. Benchmarks that indicate extensive downsizing and outsourcing are balanced by others that suggest stronger headquarters influence or more extensive shared services. In order to push through a successful corporate centre transformation, it is necessary to design a staff that responds to the specific needs of the company and is fit for the purpose it is intended to serve. For several years now, we have been developing an approach to help companies to do this. At Ashridge Strategic Management Centre, we have carried out extensive research on the rôle of the corporate centre 83 RE-DESIGNING THE CORPORATE CENTRE and its contribution to successful corporate-level strategies. Recently, we have completed a major project that has gathered data on over 600 companies in seven different countries, providing fresh information on the size, composition and determinants of headquarters staffs (see Sidebar). At PricewaterhouseCoopers, the Corporate Centre Transformation practice has undertaken consulting projects for several major clients that were reassessing their corporate centres. In this article, we summarise the approach to corporate centre design which we have devised. We believe the approach leads to real change and results in corporate centres that focus on value creation and are genuinely fit for purpose. Sidebar: The Ashridge Surveys During the period from late 1997 to 1999, Ashridge Strategic Management Centre (ASMC) led a major international research collaboration on the size and structure of corporate headquarters staffs. Data was gathered on over 600 companies, located in the UK, the USA, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan and Chile. The research partners were Michael Goold and David Young (ASMC, UK), David Collis (Yale University, USA), Georges Blanc (HEC, France), Rolf Bühner (University of Passau, Germany), Jan Eppink (Free University, Netherlands), Tadao Kagono, (Kobe University, Japan), and Gonzalo Jiménez Seminario (University Adolfo Ibañez, Chile). The research was sponsored by PricewaterhouseCoopers. Reports on the UK research, Effective Headquarters Staff and Benchmarking Corporate Headquarters Staff, were published in 1999 by ASMC, and a report on the international comparisons, Corporate Headquarters: An International Analysis of their Roles and Staffing, was published by Financial Times Prentice Hall in 2000. A major finding from the research was that there are large differences between companies in the size and composition of their headquarters staffs. For example, the size of corporate headquarters varied from about 10 to well over 1000 for companies with 10,000 employees in total. And, while some companies avoid headquarters staffs in functions such as R&D and marketing altogether, others have substantial departments in these areas. These differences reflect different views about the right rôle and responsibilities for headquarters. There is no standard model for successful corporate headquarters. There are however four key factors that account for many of the differences between headquarters. These factors are company size, the amount of functional influence exerted by the headquarters, the level of linkages between businesses in the portfolio, and the corporate policy on shared services. Bigger companies, with stronger functional influence and more linkages between their businesses, or with a policy of providing extensive shared services tend to have 84 larger, more multi-functional headquarters. For example, headquarters size increases by about 60–70 per cent with each doubling of company size, and companies in which shared services staff represent 40 per cent or more of headquarters have more than three times as many HQ staff in total as those in which they represent 20 per cent or less. Other factors, such as industry sector or geographical spread, also matter, but are less strongly or less directly correlated with headquarters size and structure. There are also differences in the pattern of headquarters between countries. In general, the European countries surveyed were remarkably similar. But headquarters in the US and, in particular, in Japan were larger. US companies appear to have bigger and more influential staffs in areas such as IT, purchasing, marketing and R&D. In Japan, the human resources function is particularly strong and large. US companies are more satisfied with the performance of their headquarters, and are in most cases increasing their size and influence, and the amount of services they provide. In Europe, and even more in Japan, there is less satisfaction with HQs, and the trend is to reduce staffing. Three Rôles of the Corporate Centre The essential starting point in any corporate centre re-design is to recognise that headquarters staff play three very different rôles (see Table 1). The first rôle, which we call the minimum corporate parent rôle, involves discharging the legal and regulatory obligations of the company and meeting minimum standards of due diligence in corporate governance. This rôle has limited ability to create value, but is necessary for any corporation. It should, however, be possible to discharge the minimum corporate parent activities with relatively few staff. Most companies greatly overestimate the size of the staff necessary for the minimum corporate parent rôle, so a pressure for leanness and benchmarking against leading-edge companies are likely to be good disciplines. The second rôle, which we call value-added parenting, is about how the corporate parent influences and adds value to the businesses. It is therefore closely related to the company’s corporate strategy, which should lay out the value-added rationale for why it makes sense for all the businesses in the group to fall under common ownership. Staff who add real value for the businesses, for example by helping to develop and share core competences, are clearly justified, and it may well be desirable to maintain large staffs in functional areas that are important sources of value. But staff groups in this rôle that do not have a demonstrable added-value rationale should be downsized or eliminated, since there will otherwise European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 RE-DESIGNING THE CORPORATE CENTRE Table 1 Three Rôles of Corporate Headquarters Rôle Examples Characteristics Minimum corporate parent Raising finance, basic control, compiling and publishing accounts, submitting tax returns Essential Value-added parenting Strategic guidance, stretching targets, leveraging corporate resources, facilitating synergies Shared services Information systems, payroll, training, transaction processing be a danger of excessive costs and misdirected influence. The third rôle, which we call shared services, is about providing centralised services to the businesses. Companies’ policies concerning shared services differ widely. Some decentralise most or all services to the businesses, believing that centralised services are seldom truly cost effective and responsive to business needs. Others prefer to outsource services to third parties. Yet others believe that shared services at the centre, at least in selected areas, can be highly effective, whether due to focused management attention, economies of scale, or opportunities for standardisation. One way to downsize the corporate centre is certainly to decentralise or outsource shared services, which often employ large numbers of people. But, with increasing emphasis on cost competitiveness, the trend amongst many leading companies seems rather to be in favour of centralising services, provided that they are set up as separate units with a dedicated focus on service provision and customer responsiveness. The justification for corporate centre staffs is fundamentally different for each of the three rôles. The design process therefore needs to give separate consideration to each of them. Minimum Corporate Parent Rôle For any corporate parent, there are some unavoidable tasks, such as obligatory legal and regulatory requirements and basic governance functions. Legal and regulatory tasks include, for example, preparing annual reports, submitting tax returns, and ensuring that relevant legislation on issues such as health and safety or the environment is observed. Any corporate entity must discharge these compliance responsibilities. It is also necessary to undertake basic governance European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 Not easily devolved to divisions Discretionary Believed by corporate managers to add value to the business divisions Needed by divisions Could be devolved or outsourced Centralisation believed to provide economies of scale, scope or specialisation functions and show due diligence in representing shareholder interests. The corporate parent must establish a structure for the company, appoint the senior management, raise capital and handle investor relations. It must also implement some form of basic control process, so that it can authorise major decisions, guard against inappropriately risky or fraudulent decisions, and check that delegated responsibilities are being satisfactorily performed. The extent of these necessary governance and due diligence tasks is hard to determine precisely. The strict legal requirements are limited, so it is more a matter of what the chief executive feels obliged to do in order to satisfy his or her fiduciary duties to the shareholders. We call these unavoidable activities the minimum corporate parent rôle. They are the bare minimum necessary to maintain the corporate entity in existence. A vital question concerns the size of the staff needed for minimum corporate parent activities. The Ashridge Strategic Management Centre survey research has allowed us to estimate the numbers of staff required. These numbers are strikingly low. For example, a company with 10,000 employees in total can handle minimum corporate parent activities with only about 15 staff, while a company with 50,000 employees needs only about 35 staff for these tasks (see sidebar). Table 2 shows the total number of staff in the departTable 2 Lean Minimum Corporate Parent Staffs Company size (no. of employees) BAT ITT Ocean Nucor 141,500 58,497 11,400 6800 No. of staff in minimum corporate parent departments 44 55 17 17 85 RE-DESIGNING THE CORPORATE CENTRE ments mainly concerned with minimum corporate parent activities (general management, legal, financial reporting and control, treasury and tax) for four companies with lean headquarters, BAT, ITT, Ocean and Nucor. Since the staff in these departments will be carrying out some activities that go beyond minimum corporate parent requirements, the numbers probably overstate the true size of the minimum corporate parent staff in each case. Through statistical analysis of this information, we were able to identify the factors that are most significant drivers of corporate headquarters staff. From the analysis, we produced ‘ready reckoners’ for the total corporate centre staff and for each department that calculate ‘par’ (i.e. median) staff numbers for any company, adjusted for a variety of factors reflecting its size, the nature of its businesses, and the policies of its corporate centre.1 What is more, significant economies of scale in minimum corporate parent activities are possible. The size of minimum corporate parent staff tends to increase by no more than about 50 per cent with each doubling of company size. Large companies should have a lower proportion of minimum corporate parent staff than small ones. Par staffing of minimum corporate parent activities can be assessed by focusing on general corporate management, together with the treasury, taxation, financial reporting and control, and legal departments. These are the main departments concerned with minimum corporate parent activities, and are present in over 90 per cent of all companies. Staff numbers in these departments are similar in the USA, the UK, France, Germany and the Netherlands. To benchmark staff numbers involved in minimum corporate parent activities, we used our ready reckoners to estimate par staffing for these departments, on the assumption that the departments are not trying to influence the businesses, responsibilities that have more to do with value-added parenting than with the minimum corporate parent rôle. Since these departments perform other tasks (e.g. service provision) that go beyond the minimum corporate parent rôle in many companies, we also used lower quartile numbers as our benchmarks. Putting a focus on minimum corporate parent activities achieves three purposes. Firstly, it brings out how small a truly lean corporate headquarters can be. The benchmarks derived from our survey represent a challenge for most companies: how could we carry out the minimum necessary tasks of the corporate centre in a professional manner with a staff of no more than, say, 20 people? This forces some toughminded new thinking about headquarters. Secondly, the discipline of squeezing down minimum corporate parent staff numbers reduces inadvertent value destruction. Due diligence is often a matter of checking what the businesses are planning or doing, a responsibility which even well-intentioned and competent corporate staffers with time on their hands can easily convert into unproductive interference and second guessing. To avoid this sort of value destruction, planning and control activities that simply fulfil minimum corporate parent responsibilities should be strictly limited. Thirdly, the minimum corporate parent staffing provides a good baseline for designing the corporate centre. Although there are some obligatory tasks that any headquarters must carry out, these tasks account for only a small proportion of most corporate centre staff numbers. Any staff over and above those needed for minimum corporate parent tasks must then be justified with a clear value-added rationale. Sidebar: Minimum Corporate Parent Staff The ASMC surveys gathered detailed data on the size, cost, rôles and departmental composition of headquarters staff. They also collected information on overall company sizes, the nature of the businesses in each company (e.g. relatedness, geographical spread) and the policies of the corporate centre (e.g. influence levels, linkages between business). 86 The resulting benchmarks for European companies, are shown below. US benchmarks are approximately 25 per cent higher. Company size Staff required (# of employees) for minimum corporate parent rôle 2000 5 5000 9 10,000 15 20,000 23 50,000 43 100,000 65 Minimum corporate parent staff per 000 employees 2.5 1.8 1.5 1.1 0.9 0.6 Other common departments (present in over 80 per cent of companies) are corporate planning, government and public relations, internal audit, and human resources. Using similar assumptions in the ready reckoners for these more discretionary departments adds around five to minimum corporate parent staff numbers for a company with 10,000 employees and around 15 for a company with 50,000 employees. To be more specific, a company with 20,000 employees that aspires to carry out the minimum corporate parent activities as leanly as possible should be able to manage with no more than 20–25 people, including support staff, made up approximately as follows: European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 RE-DESIGNING THE CORPORATE CENTRE 4–5 General Management 3–4 Legal 5–6 Financial Reporting, Control, Internal Audit 3–4 Treasury and Tax 2 Planning 2 Human Resources 2 Government and Public Relations Truly lean corporate centres might do without the Planning, HR, and Government and PR departments. It is evident that the minimum corporate parent staff numbers needed can be very low. Value-Added Parenting Rôle Any valid corporate strategy needs to be based on some clear ideas about how value can be added by the corporate parent. If there are no important sources of parenting value-added2, the businesses would almost certainly be better off operating independently, and a break-up should be considered. The value-added parenting rôle of the corporate centre is therefore vital. Different companies concentrate on very different sources of parenting value-added. Pfizer and Corning spend heavily on corporate R&D, and have seen big pay-offs in terms of new product development. Dow emphasises manufacturing excellence, and has a strong corporate manufacturing function to influence its businesses and co-ordinate multibusiness manufacturing sites. Rio Tinto adds high value through improved planning of mining operations, using the expertise of its corporate technical staff for this purpose. BP Amoco has pushed hard to create a high performance culture throughout the company by setting stretching targets and agreeing personal performance contracts between business unit heads and the CEO. Virgin leverages its widely recognised corporate brand into a whole variety of businesses, from airlines through financial services to internet access. Some sources of parenting value-added depend on corporate centre staff support. For Pfizer, Corning, Dow and Rio Tinto, high quality staff groups in the relevant functional areas are essential to creating and delivering the value. But other sources of parenting value have less to do with corporate staff. In BP, the performance culture depends much more on line management than on finance or planning staffs. And in Virgin, the value of the brand is enhanced much more by Richard Branson personally, than by the activities of the tiny corporate staff. It is not surprising, therefore, that the Ashridge surveys show a wide variation in the size and departmental composition of value-added parenting staffs. Since the corporate strategy for adding value differs from company to company, the appropriate level and European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 nature of staff groups in the value-added parenting rôle is bound to differ. This means that simple benchmarking of the size and cost of these staffs is likely to be misleading, since it does not take account of the corporate strategy differences. What is clear from the Ashridge research, however, is that the level and nature of corporate functional influence is a driving factor in shaping headquarters staff. For example, companies that guide most IT decisions from the centre and have most of the IT staff at the headquarters have IT departments that are over ten times larger than companies with a more decentralised approach.3 Corporate centres in the USA tend to be substantially larger than those in Europe, mainly because US companies generally have more influential and hence bigger staffs in functions such as IT, purchasing, marketing and R&D.4 Size of staff, however, is only one indicator of effectiveness in delivering the desired influence. Indeed, the surveys show that large headquarters staffs are not generally rated more effective in supporting corporate strategy than small ones. It is the skills of the staffs and the value-added from their activities that matter more than their numbers or cost. Most companies accept the logic of focusing on the added-value of the corporate centre. Surprisingly few, however, make this a key design criterion or attempt to measure it. We believe that all corporate function heads should be required to identify what, if any, value their departments intend to add, and how many staff in their departments are playing a value-added parenting rôle. They should also be expected to report on the value they have actually added at least annually. Shell has recently adopted this discipline for its corporate centre, and it has sharpened thinking about the real sources of parenting value-added, and about the staff resources needed to support them. The opinions of business managers should be given strong weight in making the assessments of value-added, and can provide a salutary balance to the views of overoptimistic corporate staffers. Large corporate centre staffs in the parenting valueadded rôle may therefore be fully justified, provided they are genuinely needed to support value creation opportunities. It would clearly be wrong for a Pfizer, a Lucent, a Dow, or a Rio Tinto to cut back on the staff groups that are critical to their corporate strategies. But where the value-added rationale is vague or unconvincing, or where the evidence suggests that the actual impact on performance has been limited or even negative, staff in the parenting value-added rôle are ripe for downsizing or elimination. A crucial challenge for corporate centre re-designers is to identify what important opportunities exist for the parent to add value. In what areas could the businesses improve their performance most markedly, 87 RE-DESIGNING THE CORPORATE CENTRE and what can the parent do to help? What unusual skills or resources does the parent possess, and how could they be used to leverage business results? This is usually much more a matter of finding highly company-specific opportunities rather than implementing general good management practice. A generally well-designed budget process is seldom a key source of added-value, whereas a performance contract process designed specifically to allow John Browne to challenge BP’s oil industry managers to achieve top performance can be far more powerful. Identifying some major opportunities for valueadded parenting is a pre-condition for a successful corporate centre re-design.5 Shared Services Rôle Shared services are activities carried out centrally on behalf of the divisions or business units of a company. The services may be standard, process-driven transactional activities, such as payroll or payments processing, or they may be more complex, professionally-driven expert services, such as applications software development or business intelligence. The divisions or businesses, which would have to carry out or buy in the services themselves if they were not provided by the centre, normally have some control over the work done. Shared services staff can account for a high proportion of total headquarters staff. They represent, on average, 43 per cent of total HQ staff in the UK. In companies with a strong commitment to shared services, these numbers can be even higher. (see Sidebar: Re-designing the Corporate Centre at Burmah Castrol). Historically, many companies have been concerned about whether their shared services were really cost effective and responsive. Functional heads have often run shared services as parts of their departmental empires rather than as client-responsive services for the businesses, and business managers have complained that their needs were disregarded and that better and more cost-effective services could be bought in from third party providers. Many corporate chief executives have therefore sought to reduce the size and scope of shared services, and, particularly, to consider outsourcing alternatives. One of the easiest ways of downsizing headquarters has been to squeeze the large numbers of people providing shared services. More recently, the trend to cut back on shared services has begun to reverse. Increased pressure on cost competitiveness, the drive for service improvements, and new technology applications are making companies think again about the potential benefits from centralised services, and a new, stronger concept of 88 shared services has emerged. Under this concept, the shared services are provided by organisationally distinct, business-like units, separated out from other functional or departmental activities, and often run by someone in a dedicated general management rôle. The strong definition implies something very different from a traditional corporate centre service function, with a much more dedicated, customer-responsive and performance-driven approach. Many proponents of shared services, such as Dupont, Shell and ABB, believe that the benefits of shared services only really emerge under this type of approach (see Sidebar: Dupont’s Global Services Business). The rationale for the renewed enthusiasm for shared services is that, with appropriate management, they are capable of yielding very large performance improvements. For example, 20–50 per cent cost savings, together with improvements in service levels, are quoted by some supporters of shared services.6 The main source of these performance improvements seems to be the focused management attention that shared service units can give to activities that were previously neglected or poorly managed. Ciba Specialty Chemicals was able to achieve a 50 per cent headcount reduction in their new Business Support Centres (finance and IT), while achieving faster and more error-free reporting, on increased volumes of sales. This was achieved through giving more attention to process improvements, adoption of best practices, and better staff morale and development. It is therefore not so much a matter of centralising services to reap economies of scale as creating a unit or units whose whole purpose is to provide the relevant services effectively and responsively (the strong concept of shared services). If the services are just one part of the responsibilities of a function head, who may well be much more interested in advising the CEO and setting corporate functional policies than in service provision, they will not get the dedicated attention they need. Equally if the services are imposed on the businesses with little attempt to benchmark them against outside providers, to take account of business needs, or to measure their performance, they are not likely to be customer-responsive or cost-effective. Old-style shared services that are insulated from market pressures and are lowstatus, low-attention parts of monolithic departmental empires remain good candidates for downsizing or outsourcing. But new-style, strong form shared services may well be justified, even if they represent a large proportion of the corporate-level headcount. Sidebar: Dupont’s Global Services Business Dupont has been a leader in shared services for some years, and, in early 1999, set up a new, separate European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 RE-DESIGNING THE CORPORATE CENTRE organisation, called the Global Services Business (GSB). It covers a wide range of services, including accounting, legal services, people processes, and sourcing and value chain processes, and employs 6000 people globally, over 6 per cent of Dupont’s total workforce. GSB’s mission is ‘to help Dupont businesses do business better’. To achieve its mission, it is attempting to operate, as far as possible, like a business itself. In other words, it is driven by the demands from its Dupont customers, recognises that it must deliver value in excess of its charges and better than outside suppliers, and concentrates on reliability and responsiveness. Business unit heads sit on the GSB’s advisory board, together with GSB senior executives, service level agreements govern the relationship between GSB and its customers, and regular customer satisfaction surveys are carried out. In this way, customer focus is central to everything GSB does. Businesses are free to buy services from GSB or to go elsewhere. They are charged for actual consumption at an agreed, fixed rate or price. These prices are based on shared forecasts of usage. Transparency of services provided, costs and prices are important to the relationship between GSB and its customers. In addition to professionalism in service offerings and service processes, a critical element in GSB’s success is staff attitudes. The people in GSB are far more motivated as part of a dedicated, customer-responsive, cutting-edge, quasi-business than they were in the old central functions. The combination of professionalism, expertise and commitment is already beginning to yield major performance improvements. Summary Corporate centre re-designs are an integral component of many new corporate strategies and transformation processes. But these re-designs often fail to achieve the effectiveness, agility and value-added that are desired. As a result, enthusiasm for the task flags, line managers lose respect for the corporate centre, and corporate staffs become demoralised and demotivated. The remedy is to base the corporate centre design process on the three rôles we have described.7 In the sidebar, we describe the use of the approach at Burmah Castrol. Sidebar: Re-designing the Corporate Centre at Burmah Castrol In 1998, Burmah Castrol embarked on a re-design of its corporate centre. At the time, its turnover was £3 billion, and it had four global business units in Lubricants and six global business units in Speciality European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 Chemicals. The corporate centre (‘everything that isn’t part of a business’) had a staff of around 400 people.8 Burmah Castrol began with an activity analysis that showed that 80 per cent of the staff were engaged in shared services, with much smaller numbers concerned with minimum corporate parenting and value-added parenting. Laying out who was playing which rôles was vital. ‘Previously, people were not clear about the nature of their responsibilities. In HR, for example, individuals were unsure if they were supposed to be advising the businesses what to do (parenting) or asking them what they wanted (services). If you can get clarity on the rôles, everything else follows’, stated Jonathan Vickers, the leader of the transformation project. Benchmarking of the minimum corporate parent activities showed that Burmah Castrol was broadly in line with its peer group in terms of numbers. Furthermore, there were no evident shortcomings in the professionalism with which these tasks were being carried out. Only modest changes in these areas were needed. Identifiying major sources of parenting value-added was harder. The CEO and the senior corporate management worked through a long list of possible sources of value-added, but concluded that many of them had limited potential, or entailed downside risks of excessive costs or negative influence. Some important opportunities did, however, emerge, including the development of managers to run small local operations as part of global businesses, and the sharing of best practices concerning ‘customer intimacy ’ (applications development, relationship management, service responsiveness). By contrast, it was decided that some other parenting activities should be eliminated, because they were never likely to create positive net value-added, including ‘the parenting that we didn’t even know we were doing’. The sources of parenting value-added were then extensively discussed and refined with the business managements, yielding a much clearer sense of where the real value lay and how to get at it. This led on to re-design of the corporate centre to implement the parenting value-added rôle more effectively. The re-design also paid particular attention to the shared services, since they accounted for such a large part of the total corporate centre. Discussions with both the providers and users of the services rapidly showed that there were problems to be addressed and differences in perspective between the centre and the businesses. ‘We don’t feel that what we do is appreciated’ (Service Department). ‘We have conflicting priorities and no way to resolve them’ (Service Department). ‘What do they do at the centre? No, really, I don’t know’ (Business). 89 RE-DESIGNING THE CORPORATE CENTRE The cost effectiveness and importance of each service were assessed through a series of workshops involving both service providers and business users, together with a benchmarking process. This led to the elimination of some unwanted services, outsourcing of some commodity items, and the establishment of a new Services Centre for the remaining services. The Services Centre was set up to be culturally and organisationally separate from the rest of the corporate centre, with a single general manager in charge reporting to the CEO. It included all the servicerelated activities of the IT, HR, Legal and Accounting departments, but not their parenting value-added or minimum corporate parent activities. The Services Centre established service contracts with the businesses, using simple charging mechanisms and giving ultimate control to the businesses. This created better mutual understanding, and led to lower costs. The Services Centre’s attitude has also become more service oriented and customer responsive. The result of the re-design has been a more effective corporate centre, better attuned to the needs of Burmah Castrol. Headcount is down by about 10 per cent. But the real benefit has had much more to do with added value and effectiveness than with simple downsizing and cost reduction. The first step is to establish the staff needed for the minimum corporate parent rôle. This is a matter of ensuring that all corporate obligations can be professionally discharged, while weeding out unnecessary activities that may be value destroying. Aggressive benchmarking of staff numbers against comparable companies is desirable to provide some reference points. porate centre value added also need to be designed, but must take account of the costs and the risks of misguided interference as well as the upside potential. The third step is to focus attention on shared services. The service activities of central departments need to be broken out and tested for cost effectiveness and responsiveness. This will involve benchmarking against other possible providers, as well as consulting the business users. The potential benefits from setting up a separate, dedicated shared services organisation need to be considered before making decisions on whether and how to provide each service centrally. If shared services are set up or retained, the businesses should have some freedom to opt out if they are dissatisfied with the services provided. This means that shared services will only survive in the long run if they are delivering good value to their business customers. Designing the corporate centre in this way gives a much sharper justification for the existence of different sorts of staffs, allows both headquarters managers and business managers to see what staff rôles are worthwhile, and identifies the skills and competences needed. By thinking through the three rôles, it is possible to create a genuinely fit-for-purpose corporate centre that supports the corporate strategy and delivers real value. Notes 1. For a full description of the ready reckoners see Young et al. (2000); Young and Ullmann (1999). 2. The PricewaterhouseCoopers’ term is corporate centre value propositions. 3. See Young and Ullmann (1999, p. 75). 4. See Young et al. (2000, Ch. 6). 5. See Goold et al. (1994, Ch. 12) for a fuller discussion of how to identify value-added parenting opportunities. 6. Gunn Partners Inc., for example, have carried out survey research with 30 companies that supports these conclusions. See Gunn Partners (undated). 7. See Pettifer (1998) for a fuller description of such a process. 8. As part of the general trend to consolidation in the oil industry, in July 2000 BP Amoco acquired Burmah Castrol, and Burmah Castrol ceased to have a separate corporate headquarters. The second step is to identify the major intended sources of value added by the corporate centre, each of which should have the potential to make a measurable impact on corporate results (e.g. 10 per cent or better uplift in profits). Once these sources of parenting value-added have been laid out, it is essential to think through in detail how they will be implemented, and, in particular, to design the staff resources and processes needed to support them. Companies that can find no major parenting value added opportunities should consider demerger, or else retrenchment of the corporate centre to minimum corporate parent activities only. References Provided that some large sources of parenting valueadded have been identified, it is also appropriate to include other secondary sources of value-added in the design of the corporate centre. Corporate purchasing, for example, may not add enough value to provide a rationale for the group’s existence. But if we are going to have a corporation at all, there may well be some value available from centralising selective areas of purchasing. The staffs and processes required to support these secondary sources of cor- Goold, M., Campbell, A. and Alexander, M. (1994) CorporateLevel Strategy. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester. Gunn Partners (undated) Introduction to Shared Services. Gunn Partners Inc., Boston. Pettifer, D. (1998) Corporate Centre Transformation. PricewaterhouseCoopers, London. Young, D. and Ullmann, K.D. (1999) Benchmarking Corporate Headquarters Staff. Ashridge Strategic Management Centre, London. Young, D. (2000) Corporate Headquarters: An International Analysis of their Roles and Staffing. Financial Times/Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 90 European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 RE-DESIGNING THE CORPORATE CENTRE MICHAEL GOOLD, Ashridge Strategic Management Centre, 17 Portland Place, London W1N 3AF. michael.goold@ashridge.org.uk Michael Goold is a director of the Ashridge Strategic Management Centre. His research interests are concerned with corporate strategy and the management of multi-business companies, and he runs the Centre’s programme on Strategic Decisions. His publications include Synergy: Why Links Between Business Units Often Fail and How to Make Them Work (Capstone, 1998), Corporate-Level Strategy: Creating Value in the Multibusiness Company (John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 1994) and Strategic Control: Milestones for Long-Term Performance (Financial Times/Pitman, 1990). DAVID PETTIFER, PricewaterhouseCoopers, 1 Embankment Place, London, WC2N 6NN, UK. David Pettifer is a Leading Partner in the Global Strategic Change Practice of PricewaterhouseCoopers where he is responsible for assisting major clients with the design and implementation of value-focused corporate centres. He has published several articles on Corporate Centre Transformation and leads PwC’s relationship with Ashridge Strategic Management Centre. DAVID YOUNG, Ashridge Strategic Management Centre, 17 Portland Place, London W1N 3AF. David Young is an associate of Ashridge Strategic Management Centre and an independent consultant. He has led ASMC’s research on the size, structure and rôle of corporate headquarters staff over the last seven years, and his management guides, Effective Headquarters Staff and Benchmarking Corporate Headquarters Staff are recognised as the premier publications in their field. European Management Journal Vol 19 No 1 February 2001 91