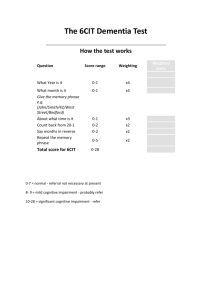

Received: 10 February 2017 Accepted: 18 September 2017 DOI: 10.1002/gps.4822 RESEARCH ARTICLE Evaluation of MESSAGE communication strategy combined with group reminiscence therapy on elders with mild cognitive impairment in long‐term care facilities | Peng‐cheng Liu1 Huan‐huan Zhang1,2 Mei‐ling Zhang1 | Jiao Sun1 1 School of Nursing, Jilin University, PR China 2 The Second Affiliated Hospital Zhejiang University School of Medicine, PR China Correspondence Jiao Sun, School of Nursing, Jilin University, PR China, No. 965 Xinjiang Street, Chaoyang District, Jilin, PR China. Email: sunjiao@jlu.edu.cn Objective: | Jie Ying1 | Ying Shi1 | Shou‐qi Wang1 | This study aims to evaluate combined effects of MESSAGE communication strategy and group reminiscence therapy (GRT) on elders with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in long‐term care facilities in Changchun, China. Methods: This study is a nonrandomized controlled trial. Subjects included 60 elders with MCI. Participants were divided into intervention (MESSAGE communication strategy combined with GRT) and control groups (without any intervention). Primary outcomes comprised cognitive function and quality of life of elderly people, as measured by the Beijing version of the Montreal Cognitive Funding information Jilin University, Grant/Award Number: 2016224 Assessment and the Chinese (mainland) version of Short‐Form 36 Health Survey assessment. Results: We observed significant changes in cognitive function with mean difference of 1.962 after 12 weeks (P = .000; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.341, 2.582), delayed memory dimension of 1.115 (P = .003; 95% CI = 0.417, 1.813). The intervention group exhibited the following improvements: general health of 14.731 (P = .000; 95% CI = 8.511, 20.951), mental health of 21.038 (P = .000; 95% CI = 17.301, 24.776), role‐emotional of 26.925 (P = .003; 95% CI = 10.317, 45.533), and vitality of 14.231 (P = .000; 95% CI = 10.084, 18.377). Conclusions: Using a sample of Chinese elderly people with MCI and residing in long‐term care facilities, we concluded that application of MESSAGE communication strategy combined with GRT resulted in improved cognitive function and quality of life. KEY W ORDS elders, group reminiscence therapy, long‐term care facilities, MESSAGE communication strategy, mild cognitive impairment 1 | I N T RO D U CT I O N illness that progresses through a period when symptoms are initially mild and interventions possibly work more effectively. Among Chinese Dementia comprises progressive neurodegenerative disorders that elderly people (age ≥ 60 y), incidence rate of MCI totals 12.7%,4 and affected 46.8 million people worldwide in 2015, with 9.5 million 10% to 15% of people with MCI exhibit Alzheimer's disease progres- (20.3%) identified in China; in people aged 60 years, prevalence of sion each year5,6; therefore, early intervention must be highly consid- dementia reaches 4.3%.1 In several regions in China, prevalence of ered for people such condition. In recent years, increasing attention Alzheimer's disease accounts for focused on nonpharmacotherapy practices, such as cognitive therapy,7 majority of dementia cases among elderly people. Dementia not only music therapy,8 and reminiscence therapy.9 Basing on improved affects cognitive function, mood, and daily activities of individuals preservation of long‐term memories than recent episodic memories but also quality of life of their families combined with staggering in both older and dementia patients,10 researchers discovered that economic burden on relatives and nations. reminiscence therapy can be significantly used to stimulate long‐term 2 dementia totals 0.8% to 7.5%. Corbyn3 showed that early diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stems from the assumption that people with dementia feature an Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:613–622. memories of patients with dementia with aid of guide materials, such as old photos, life story books, recordings, and old songs. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/gps Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 613 614 ZHANG ET AL. Group reminiscence therapy (GRT) can encourage participants to interact and share their own life experiences. Current research focuses Key points on improving cognitive functions, quality of life, and decreasing depres- • This work is the first study to apply communication sion of patients with dementia and elderly people with MCI using strategy combined with group reminiscence therapy GRT.11 Reminiscence therapy combined with other cognitive enhance- (GRT) among elders with mild cognitive impairment ment (process‐based cognitive training) can also improve cognition and (MCI) in long‐term care facilities in China. quality of life in elderly people with MCI.12,13 However, the study of Barban et al10 failed to confirm efficacy of this method in patients with • In redesigning theme content, application of low‐level MCI. Thus, we suggest conducting further research and discussion on multimedia information technology enables interaction effects of reminiscence therapy on elderly people with MCI in future. and attracts subjects' attention or provides enjoyment. In recent years, several studies applied multimedia information • Results indicated that multimedia information technology technology (MIT) to reminiscence therapy. Using MIT aimed at provid- can improve cognitive function and quality of life among ing health care to patients using mobile devices (eg, telephones, elders with MCI. However, limited evidence can be used computers, and televisions) to meet needs and to capture interest of to support efficacy of MESSAGE communication strategy patients. Based on MIT support for various reminiscence media, such combined with GRT on elders with MCI. type of technology can be summarized as sets of text, sound, graphics, • Researchers must explore large‐scale and well‐designed and multimedia album,14,15 daily assistance by videophone,16 music randomized controlled trials to confirm effects of game,17-19 computer interactive reminiscence and conversation aid MESSAGE communication strategy combined with GRT system,20,21 and other types. These studies showed that when on elders with MCI in long‐term care facilities in China. combined with reminiscence therapy, MIT encourages positive interactions between dementia patients and their caregivers and elicits verbal reminiscence in patients,17-21 catches their attention and improves to 9 subjects. Each subgroup followed the same intervention protocol. psychological stability,15,16 guides and navigates patients for indepen- Members of intervention group received 1‐ to 1.5‐hour session of GRT dent living,14 and enriches reminiscence material by constructing a once a week for 12 weeks. The control group included participants 20 database that includes clips video, photos, music, or other materials. who did not receive any intervention measures. Cognitive decline impairs memory and language skills, thus interfering with effective communication.22 Researchers developed 2.1 | Participants various communication strategies, such as MESSAGE strategy,23,24 Advanced Innovative Internet‐Based Communication Education strategy,25 and Internet‐Based Savvy Caregiver program26 for (in)formal dementia caregivers. These strategies not only improve care quality of caregivers but also increase effective communication between patients and caregivers. The present study used 7 basic frameworks of MESSAGE communication strategy as models to guide 23 development and implementation of GRT programs. To our knowledge, no study concurrently evaluated combination of MESSAGE communication strategy and GRT for Chinese elderly people with MCI. Our work was based on specific communication education strategy and reminiscence therapy program of a previous study, Inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the study and elderly subjects (age > 60 y) with MCI. Based on Petersen's criteria, inclusion criteria consisted of the following: (1) report of subjective memory complaint (≥1 y); (2) preserved general intellectual functioning (as estimated by Mini‐Mental State Examination [MMSE]); (3) demonstration of memory impairment by cognitive testing (as estimated by Beijing version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA‐BJ]); (4) intact ability to perform daily living activities (activity daily living scale score < 22); and (5) diagnosis of MCI. Exclusion criteria included unstable cardiac diseases, significant cerebrovascular diseases, serious hearing problems, and serious vision problems. which included elderly people with MCI in long‐term care facilities in Changchun, Jilin Province. This method is guided by MESSAGE com- 2.2 munication strategy to explore effects of GRT on Chinese traits and Based on the following formula (power: 80%; α: .05) and data of similar low‐level MIT on elderly people with MCI; it not only broadens chan- study conducted by Wang,27 sample size totaled 30 in each group. | Sample nels of reminiscence therapy but also serves as reference for MIT in application of reminiscence therapy or other nursing care intervention. n1 ¼ n2 ¼ 2 | 2 2× μα þ μβ σ2 δ2 METHODS This work is a nonrandomized controlled study conducted in long‐term 2.3 | Assessments care facilities in Changchun, the capital of Jilin Province, China. The Primary outcomes of this study included scores on MMSE, MoCA‐BJ, researcher was selected totals of 30 elderly people according to room and Short‐Form 36 Health Survey (SF‐36) assessment. Scores on numbers ahead as intervention group, whereas others were selected as MoCA‐BJ and SF‐36 served as bases for both secondary and third out- control group (totals of 3 buildings). For the intervention group, 4 sub- comes. Cognitive function and quality of life were assessed at baseline groups were formed sequentially, with each subgroup consisting of 7 and after 6 and 12 weeks. ZHANG 615 ET AL. Mini‐Mental State Examination was used to assess subjects for festival, and cooking, all of which are features of Chinese era (1930‐) cognitive changes28 and modified based on sociocultural and language and are national characteristics (Table 1). We also noted that participants characteristics of Chinese population. Cut‐off scores were over 17 for failed to provide related personal photos. However, the elderly people illiterate subjects, over 20 for those with 1 to 5 years of schooling, and commented that they also adored public pictures with sense of history over 24 for those with more than 5 years of schooling, indicating as such things trigger past memories. Considering sociocultural general normal cognitive function.29 background of China, we decided not to include the marriage theme. Beijing version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment was However, elderly people similarly look forward to true love. Thus, we translated by Wang and Xie (www.mocatest.org). It is widely studied placed marriage certificates, food stamps at different places and times, and was confirmed with satisfactory reliability and validity when varieties of kerosene lamps, and other generic photos obtained from applied on local elderly populations.30-32 Zhang and Liu33 explored the Internet into the theme of electronic album. We placed toys and school application of MoCA‐BJ in screening of MCI in elderly people living time in childhood theme. Meanwhile, we excluded the theme of life story in nursing homes in Guangzhou. Cut‐off scores of 15 to 24 on book, which is widely used for individual reminiscence therapy. Finally, MoCA‐BJ indicate MCI (without reports on educational bias). The we discussed feasibility of each theme with a nursing and geriatrics present study adopted a similar cut‐off score. specialist who selected 12 themes (see Table 2). In comparison with MMSE, MoCA performs better in screening MCI and sensitivity.29 According to the National Institute of Neurolog- 2.4.2 ical Disorders and Stroke‐Canadian Stroke, MoCA is advantageous in Based on 12 themes, we redesigned the theme content for interven- diagnosing vascular cognitive impairment.34 This method also aids in tion group, and we used Smith's MESSAGE communication strategy confirmation of MCI diagnosis as recommended by the Third Canadian as model, properly adjusted the framework of MESSAGE communica- Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia.35 tion strategy (Table 3). Our study also used reminiscence elements To measure quality of life, this study used the Chinese (mainland) (generic photos and suitable theme‐content video materials) suitable version of SF‐36 as developed by experts of Sun Yat‐Sen University of for Chinese elderly people. To engage interaction and to provide Medical Sciences, China. Short‐Form 36 Health Survey contains 36 items enjoyment, low‐level MIT was used in redesigning theme content. (9 scales). Responses were made on 2‐ to 6‐point Likert scale except for Each individual features a different life experience, and individual dif- that of reported health transition. Raw score of each eight‐SF‐36 scale ferences are large. Thus, the present study did not create relevant | Redesigning of theme content was derived by summing item scores and converting the numbers to generic video of these 3 themes: work experience, my ideals, and my values ranging from 0 to 100. High scores indicate high quality of life. achievement. As self‐introduction and memories of good times only represented the beginning and end of group reminiscence activity, 2.4 2.4.1 we also did not create any relevant generic video for these themes. GRT program | | Theme design Related research at home and abroad was first consulted and considered 2.5 | Statistical analyses 16 themes (old picture, old films, traditional Chinese opera, food stamps, Collected data were analyzed using SPSS software, Chinese version music, childhood, toys, traditional festival, school time, cooking, my ideals, 17.0. Data features were described using statistical descriptive tests, marriage, my achievement, life story book, work experience, and family). such as mean, standard deviation, and percentage. We analyzed inter- When screening for related topics, 10 individuals (age > 60 y; 5 male action group × time of repeated measures of analysis of variance with individuals, 5 female individuals) were selected through convenient groups as between‐subject factor and time of assessment as within‐ sampling in face‐to‐face survey interviews (10 min). Interviews mainly subject factor. We reported mean difference of within‐group and its focused on music, old films, old picture, marriage, childhood, traditional 95% confidence interval. TABLE 1 Interview content Type Interview Questions Aim Music Talk about Chinese opera or songs that you like To determine types of music preferred by elderlies Old films Talk about films that you have seen To find video clips that cause emotional resonance with elderlies Old photos Share your individual photos and tell their story To determine whether elderlies can provide individual photos that they associate with good memories or have profound impact on them Marriage Talk about the story of you and your wife To determine whether marriage can be a separate activity theme Childhood Share your childhood with us To determine whether toys (or games) and school time can be integrated into a theme Traditional festival Talk about your views on traditional Chinese festival To determine whether the theme of traditional festival can stimulate good memories of elderlies Cooking Talk about meals that you like to eat or you often cook To determine whether elderlies are interested in the theme of cooking Themes Self‐introduction Music Old films Electronic album Childhood Traditional festival Cooking Family Work experience Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Group reminiscence activity program Arrangement TABLE 2 1. Talk about work experience you have accumulated 2. Talk about your personal understanding of your work 1. Play relevant generic video (5 min) 2. Briefly introduce family situations 3. Share happy memories with family 1. Play relevant generic video (5 min) 2. Memories of childhood and delicious foods 3. Share home‐cooked meals or soups that you like 4. Talk about meals that you often cook 1. Play relevant generic video (5 min) 2. Take about traditional festivals that you like 3. Share interesting things that you do or observe during festivals 4. Discuss how you celebrate your favorite festivals 1. Play relevant generic video (5 min) 2. Share good times of childhood (around games/toys/school times) 1. Play electronic album (about 10 min) 2. Share stories behind photos 1. Play film clips (40 min) 2. Tell about the feeling and memory of films 3. Share films that like elderlies watching and reasons for watching them 1. Use the song machine to play classic songs 2. Share the story behind these songs 3. Encourage singing songs that elderlies like 1. Self‐introduction 2. hobbies and interests of elderly people Content Warm Animation video (Home Memory) was split with Studio by Ulead Video and played in the projection screen. Digital photos of characteristic foods of the northeastern region of China were selected and edited (approaching week 4). Then clips of soft music accompaniment (Song of brook) were inserted as background music into a series of relevant digital photos. Spring Festival documentary of China Central Television was split by Ulead Video Studio, and we inserted Spring Festival couplets and paper‐cuts into the end of this clip video. Meanwhile, clips of soft music accompaniment (Spring Festival Overture) were played consistently in the background as video soundtrack. The sand painting video (Recalling Our Lost Childhood) was split by Ulead Video Studio, and all kinds of childhood memories were presented with scrolling marquee at the end of clipped video. Then, clips of soft music accompaniment (Children) were played in the background. Brightness and size of digital photos' (generic photos of the 1930s to 1960s) adjusted by Photoshop; images were blown up and annotated by Ulead Video Studio or Windows Media Player. Then, clips of soft music accompaniment (Where Are All The Time) were inserted as background music into a series of relevant digital photos. Two films were split by Ulead Video Studio and merged, and name and age of film were introduced by word annotation. Then, we added pictures of related themes and inserted dynamic image that displayed countdown timer before the beginning of the video. When projectors and song selection system were connected, four downloaded classical songs were played, and corresponding lyrics also appeared in the projection screen. Application of Technology (Continues) 3. To stimulate good memories of elderlies and to share their happiness with one another; 2. Encourage elderlies to participate in activity and promote interaction between them; 1. To stimulate vision and auditory senses of elderlies and add fun to the activity; To build trust Aim 616 ZHANG ET AL. 617 ET AL. To adopt suggestions, improve program activities, and remain calm and optimistic toward life. Application of Technology Aim 4. To encourage self‐identity and self‐worth. TABLE 3 MESSAGE communication strategy Term Content M—Maximize attention 1. Attract attention; 2. Maintain eye contact; 3. Limit distractions E—Expression and body language 1. Relaxed and calm; 2. Shows interests S—Keep it Simple 1. Short, simple, familiar; 2. Give clear choices S—Support their conversation 1. 2. 3. 4. A—Assist with Aids 1. Electronic album; 2. Five relevant generic videos; 3. Music G—Get their message 1. Listen, watch, and actively work out; 2. Check behavior and nonverbal message E—Encourage and Engage in conversation 1. Interesting, fixed topics; 2. Talk about researchers, other elders 3 3.1 Provide sufficient time; Assist with finding words; Repeat then rephrase; Remind of the topic RESULTS | | Characteristics of respondents Table 4 summarizes baseline characteristics of respondents. A total of 53 subjects completed all sessions of the study. Study protocol was not completed by 7 (11.7%) subjects: 4 from intervention group (2 moved away, 1 was sick, and 1 went home) and 3 from control group 1. Summary of activities 2. Talk about activity themes that you like most 3. Talk about your feelings and suggestions for the activity 4. Suggestions for young people Talk about your sense of accomplishment and comforting things in your life 1. Dreams of youth 2. Talk about your efforts to achieve your ideals 3. Talk about your sentiment Content (1 went to travel with children, and 2 became sick). No significant difference was observed in age, gender, marital status, educational level, profession, religious belief, drinking situation, smoking status, and disease situation of intervention and control groups (P > .05); it pointed that subjects of the 2 groups were homogeneous. Table 5 presents total MoCA score and scores for 7 cognitive domains of MoCA. Total MoCA indicated significant effects of time, group, and group × time interaction. For visuospatial/executive function, naming, delayed memory, and orientation, significant effects of time were observed, but group or group × time interaction did not yield significant effects. Time and group × time interaction significantly affected visuospatial/executive function, naming, and language. For visuospatial/executive function and naming, significant improvements were observed in control group at 12 weeks. Intervention and control Memories of good times My achievement My ideals tion. For delayed memory, both groups showed most significant improvements at 6 and 12 weeks. Significant advancements in language were observed for the intervention group at 6 weeks. For intervention and control groups, Table 6 shows changes in various items on health‐related quality of life based on SF‐36 at baseline and 6 and 12 weeks. Time and group × time interaction significantly affected general health, vitality, social functioning, role‐ emotional, and mental health. However, social function did not Week 12 Week 11 significantly affect observed groups. For role‐physical, only time Week 10 Arrangement (Continued) Themes groups did not show enhancement in attention, abstract, and orienta- TABLE 2 ZHANG caused significant effects. For role‐physical, social function, and mental health, both groups showed significant increases at 6 and 12 weeks. The intervention group exhibited significant enhancement in general 618 ZHANG TABLE 4 Characteristics of participants at study inclusion ET AL. health, role‐emotional, and vitality at 6 and 12 weeks. Significant improvements in bodily pain were observed for each group at 6 weeks Characteristics Intervention (n = 26) Control (n = 27) P‐value but not at 12 weeks. For physical functioning, the intervention group Age (mean ± SD) 81.19 ± 5.48 80.78 ± 6.80 .81 showed slightly significant increase after 6 weeks. 60‐69 1 (3.9) 3 (11.1) 70‐79 7 (26.9) 5 (18.5) 80‐89 18 (69.2) 19 (70.4) Female sex, n (%) 21 (80.8) 17 (63.0) Illiterate 4 (15.4) 1 (3.7) Primary school 3 (11.5) 4 (14.8) Secondary school 4 (15.4) 3 (11.1) We confirmed that GRT improved cognitive function of patients with High school or technical secondary 4 (15.4) 3 (11.1) mental dysfunctions. In the present work, MESSAGE communication 11 (42.3) 16 (59.3) Education, n (%) College or above 4 | DISCUSSION .15 .54 4.1 | Effect of GRT on cognitive function of elderly people with MCI strategy was used as prototype to increase effective communication Marital status, n (%) Single .51 between elderly people with MCI and researchers and to reduce .26 negative effects of ineffective communication on intervention effect. 1 (3.8) 0 (0.0) Married 10 (38.5) 15 (55.6) and evaluation, a 12‐theme program of group reminiscence activities Divorced 2 (7.7) 0 (0.0) was developed for each theme to stimulate life experience and good 13 (50.0) 12 (44.4) Widow Occupational status, n (%) Original GRT program was also used as basis. Finally, through screening memories in the intervention group. The following conclusion was then .23 drawn: A 12‐theme program of group reminiscence can actively improve Farmer 0 (0.0) 4 (14.8) Worker 9 (34.6) 4 (14.8) Technicians 2 (7.7) 1 (3.7) MIT to individual reminiscence therapy or GRT. Significant interven- Functionary 4 (15.4) 4 (14.8) tion effect was also observed in language and memory function of Teacher 5 (19.2) 5 (18.5) people with dementia.36,37 The present study used Ulead Video Studio Other 6 (23.1) 9 (33.4) Religion, n (%) None cognitive function, especially delayed memory, of elderly people. With continuous its development researchers gradually applied and Windows Media Player to edit digital photos with special signifi.61 cance and time characteristics. Soft background music was then added 23 (88.5) 23 (85.2) to the electronic album. Existing activities were also added in line with Buddhism 3 (11.5) 3 (11.1) themes of existing complete videos, such as the old films Five Golden Christian 0 (0.0) 1 (3.7) Flower and Landmine War, the documentary Spring Festival, and other 23 (88.5) 22 (81.5) Sometimes 2 (7.7) 5 (18.5) Often 1 (3.8) 0 (0.0) Drinking status, n (%) Never clips. Video clips were then integrated and edited using story to Smoking status, n (%) Never .32 stimulate intervention of episodic memories. When using music as theme of activities, machine was required. The songs Let's Sway Twin Oars, Shooting Back, and others were played in the projection screen. .37 Lyrics were prepared, and tracks were played, allowing participants 24 (92.4) 24 (88.9) to sing together. As a result, improvement was noted in recall ability Sometimes 1 (3.8) 0 (0.0) of familiar songs and language skills of intervention group members Often 1 (3.8) 4 (11.1) Disease status, n (%) Without alone or with other subgroups and subgroup members, thus facilitating .86 language communication and memory function among participants. 5 (19.2) 5 (18.5) Results of this study showed that increase in delayed memory may With one kind of disease 15 (57.7) 14 (51.9) benefit from MoCA scale of 5 words in 3 repetitive memories gener- 2 or more than 2 kinds of diseases 6 (23.1) 8 (29.6) Genetic history, n (%) ated by exercise. A longitudinal study38 showed that twice‐repeated practice effects affected memory of patients with MCI; through .58 story‐memory and list‐learning tests, one study39 also showed signifi- 25 (96.2) 25 (94.3) cant effects of practice on delayed recall of MCI patients. Thus, based Dementia 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) on practice effects and tolerance of elderly people to continuous Other 1 (3.8) 2 (5.7) intervention plan, group reminiscence program should be adjusted Without ADL (mean ± SD) 15.27 ± 2.13 15.70 ± 2.42 .96 and improved in future studies. This finding disagrees with decline in MMSE (mean ± SD) 25.73 ± 2.38 25.81 ± 2.51 .90 orientation scores among elderly people with MCI in the 2 groups. Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination. Possibly, in long‐term care facilities, admitted elderly people claim that they lack time perception. With increased degree of cognitive impair- ***P < .001, ment, time‐directed decline serves as sensitive indicator for cognitive **P < .01, and. function of patients.40,41 Therefore, early intervention is needed by *P < .05. elderly people at MCI stage to strengthen training in time orientation. Intervention Control t/Z P Intervention Control Z P Intervention Control Z P Intervention Control Z P Intervention Control Z P Intervention Control t/Z P Intervention Control Z P Visuospatial/ Executive function Naming Attention Language Abstract Delayed memory Orientation 5.92 ± 0.27 5.59 ± 0.69 −2.09 0.037* 1.65 ± 1.44 1.41 ± 1.08 −0.854 0.393 0.77 ± 0.77 0.74 ± 0.66 −0.029 0.977 1.69 ± 0.62 1.63 ± 0.57 −0.103 0.918 4.50 ± 1.33 4.48 ± 1.16 −0.184 0.854 2.54 ± 0.65 2.74 ± 0.53 −1.285 0.199 2.35 ± 1.23 2.81 ± 1.11 −1.456 0.151 19.42 ± 2.56 19.41 ± 2.21 0.024 0.981 Baseline Mean ± SD 5.77 ± 0.51 5.41 ± 0.75 −2.004 0.045* 2.04 ± 1.11 1.78 ± 1.05 0.877 0.384 0.69 ± 0.68 0.74 ± 0.59 −0.388 0.698 2.04 ± 0.66 1.59 ± 0.64 2.399 0.016* 4.46 ± 1.27 4.15 ± 1.06 −1.044 0.279 2.81 ± 0.40 2.74 ± 0.53 −0.328 0.743 2.96 ± 1.08 2.67 ± 1.41 −0.982 0.326 20.77 ± 2.36 19.19 ± 2.27 2.493 0.016* 6 wk 5.69 ± 0.55 5.15 ± 0.82 −2.598 0.009** 2.77 ± 0.99 2.04 ± 0.98 2.703 0.009** 0.73 ± 0.72 0.56 ± 0.75 −1.009 0.313 1.92 ± 0.69 1.56 ± 0.64 −1.836 0.066 4.42 ± 0.90 4.04 ± 1.13 −1.185 0.236 2.81 ± 0.40 2.85 ± 0.53 −0.615 0.539 3.08 ± 1.09 2.96 ± 1.19 −0.509 0.611 21.38 ± 2.00 19.22 ± 2.19 3.755 0.000*** 12 wk *P < .05. **P < .01, and ***P < .001, Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; MoCA = the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Intervention Control t P Group Effects of intervention on cognitive function Total MoCA score Outcome Variable TABLE 5 .086 .076 .212 .363 −0.154 (−0.401, 0.094) −0.185 (−0.596, 0.226) .425 1.000 −0.077 (−0.272, 0.118) 0.000 (−0.155, 0.155) 0.385 (−0.059, 0.828) 0.370 (−0.042, 0.783) .059 .814 .832 .047* −0.038 (−0.408, 0.331) −0.333 (−0.662, −0.004) 0.346 (−0.014, 0.706) −0.037 (−0.357, 0.282) .016* … .000*** .294 .000*** .477 0.269 (0.054, 0.485) 0.000 (0.000, 0.000) 0.615 (0.311, 0.919) −0.148 (−0.432, 0.136) 1.346 (0.681, 2.012) −0.222 (−0.856, 0.411) P‐value Mean Change from Baseline (95% CI) 6 wk −0.231 (−0.404, −0.057) −0.444 (−0.860, −0.029) 1.115 (0.417, 1.813) 0.630 (0.175, 1.084) −0.038 (−0.252, 0.175) −0.185 (−0.376, 0.006) 0.231 (−0.118, 0.579) −0.074 (−0.402, 0.254) −0.077 (−0.488, 0.334) −0.444 (−0.860, −0.029) 0.269 (0.087, 0.452) 0.111 (−0.016, 0.238) 0.731 (0.417, 1.045) 0.148 (−0.136, 0.432) 1.962 (1.341,2.582) −0.185 (−0.700, 0.330) 12 wk .011* .037* .003** .008** .713 .057 .185 .646 .703 .037* .016* .083 .000*** .294 .000*** .466 P‐value 0.018* 0.000*** 0.256 0.414 0.146 0.001** 0.000*** 0.000*** Time Significant 0.000*** 0.075 0.768 0.012* 0.387 0.642 0.948 0.035* Group 0.613 0.304 0.256 0.223 0.361 0.036* 0.001** 0.000*** Time × Group ZHANG ET AL. 619 Intervention Control t/Z P Intervention Control Z P Intervention Control Z P Intervention Control Z P Intervention Control Z P Intervention Control t/Z P Intervention Control Z P Mental health Role‐emotional Vitality Social functioning Role‐physical Physical functioning Bodily pain *P < .05. **P < .01, and ***P < .001, Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. Intervention Control t P Group 68.38 ± 24.29 73.74 ± 27.43 −0.751 0.456 63.65 ± 10.64 60.93 ± 11.44 0.898 0.373 30.77 ± 35.57 32.41 ± 35.23 −0.168 0.867 30.29 ± 14.65 41.20 ± 17.95 −2.42 0.019* 40.96 ± 10.20 42.59 ± 11.21 −0.553 0.582 38.46 ± 32.24 40.74 ± 31.12 −0.262 0.794 52.65 ± 10.07 55.04 ± 9.47 −0.888 0.379 38.54 ± 21.31 32.96 ± 15.32 1.097 0.278 Baseline Mean ± SD Effects of intervention on quality of life General health Outcome Variable TABLE 6 72.12 ± 17.51 76.07 ± 20.09 −0.763 0.449 65.19 ± 9.75 60.74 ± 8.05 1.816 0.075 51.92 ± 22.28 43.52 ± 21.48 1.399 0.168 46.63 ± 15.23 44.91 ± 13.54 0.437 0.664 49.81 ± 11.36 42.78 ± 8.47 2.561 0.013* 55.13 ± 24.84 41.98 ± 25.48 1.902 0.063 66.00 ± 7.69 57.19 ± 7.75 4.154 0.000*** 50.31 ± 20.23 36.85 ± 14.27 2.806 0.007** 6 wk 68.88 ± 18.00 73.00 ± 17.99 −0.832 0.409 65.19 ± 10.34 61.30 ± 9.77 1.411 0.164 57.69 ± 22.10 48.15 ± 21.85 1.581 0.120 53.84 ± 14.48 45.83 ± 16.26 1.892 0.064 55.19 ± 9.64 41.30 ± 11.65 4.721 0.000*** 65.39 ± 24.00 41.97 ± 31.48 3.036 0.004** 73.69 ± 6.71 62.44 ± 10.88 4.550 0.000*** 53.27 ± 17.86 33.81 ± 13.54 4.479 0.000*** 12 wk 3.731 (−6.291, 13.753) 2.333 (−9.369, 14.036) 1.538 (−1.578, 4.655) −0.185 (−3.925, 3.555) 21.154 (9.840, 32.468) 11.111 (−0.949, 23.172) 16.346 (8.297, 24.395) 3.704 (−4.153, 11.560) 8.846 (4.410, 13.282) 0.185 (−3.712, 4.083) 16.668 (3.894, 29.441) 1.235 (−11.686, 14.156) 13.346 (10.719, 15.974) 2.148 (−2.428, 6.742) 11.769 (6.023, 17.516) 3.889 (−1.549, 9.327) .450 .685 .319 .920 .001** .069 .000*** .341 .000*** .923 .013* .846 .000*** .343 .000*** .154 P‐value Mean Change from Baseline (95%CI) 6 wk 0.500 (−9.779, 10.779) −0.741 (−14.223, 12.741) 1.538 (−2.241, 5.318) 0.370 (−3.096, 3.837) 26.923 (11.300, 42.546) 15.741 (3.738, 27.743) 23.558 (15.694, 31.422) 4.630 (−3.951, 13.211) 14.231 (10.084, 18.377) 1.296 (−6.960, 4.367) 26.925 (10.317, 45.533) 1.234 (−15.717, 18.186) 21.038 (17.301, 24.776) 7.407 (0.988, 13.827) 14.731 (8.511, 20.951) 0.852 (−3.775, 5.479) 12 wk .921 .911 .410 .828 .002** .012* .000*** .278 .000*** .642 .003** .882 .000*** .025* .000*** .708 P‐value 0.634 0.688 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.020* 0.000*** 0.000*** Time Significant 0.260 0.135 0.361 0.900 0.006** 0.044* 0.001** 0.004** Group 0.885 0.741 0.295 0.001** 0.000*** 0.038* 0.000*** 0.001** Time × Group 620 ZHANG ET AL. ZHANG 621 ET AL. In future studies, intervention should be added to stimulate concept of 5 | CO NC LUSIO N time for elderly people with MCI delay downward trend in orientation, and improve their cognitive function. We must identify suitable interventions and the most effective methods of improving cognitive function and quality of life in elderly population. According to results of the present study, a 12‐week period 4.2 | Effects of GRT on quality of life of elderly people with MCI (consisting of 12 group reminiscence sessions) of intervention plays an active role in cognitive function (especially delayed memory) and quality of life (general health, mental health, role‐emotional, and vitality) in Quality of life of elderly people and different cognitive impairments show elderly people with MCI. To compare MESSAGE communication strat- significant differences.42 Improved in cognitive function results in higher egy, MIT, and combination of 2 effects of reminiscence therapy, future quality of life.43 The present study shows that intervention improved studies should include large samples of 2 or more randomized con- cognitive function in elderly people with MCI, thus improving their trolled trials. We also communicated knowledge and skills training to quality of life. Group reminiscence activities also promote interaction researchers or caregivers of people with MCI for their benefit. between elderly people, establish good social support system44 that reduces solitude and loneliness generated by sense of self‐conscious fatigue, and increase their vitality. In this study, elderly people with MCI were provided with group activities aimed at promoting life quality. Communication between dementia and caregivers can be promoted by MESSAGE communication strategy,23,24 thereby improving quality of life of dementia patients. This study not only used MESSAGE communication strategies to redesign the content of GRT program but ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank the participants and their families, caregiving staffs, and long‐term care facility managers who took part in the study. We also thank the postgraduate students (RN) who were involved and communicated with people with MCI. Finally, we express our gratitude to the Consultative Committee and Graduate Innovation Fund of Jilin University for the study. also implemented the program based on its basic framework to promote (non)verbal communication between researchers and elderly people with MCI. Encouragement of researchers also allowed creation of activities with pleasant and relaxed atmosphere. Such condition CONFLIC T OF IN TE RE ST None declared. aided elderly people with MCI to share personal experiences or good memories related to theme of activities. To aid intervention, the elderly SOURCE OF FUNDING people must possess positive attitude to live lives in state of pension Supported by the Graduate Innovation Fund of Jilin University— agencies and to engage in activities for self‐identity, allowing success- Project 2016224. ful physiological and psychological interventions to a certain extent. Thus, elderly people with MCI were guided with positive and optimistic attitude to help them adapt in long‐term care facilities. This study used zooming effect and annotation for a self‐made electronic album and relevant generic video of 5 themes to enrich activity content. Thus, participants felt calm and happy because of various familiar scenes that guided them during language reminiscence, resulting in easier expression and release of emotions in the activity, agreeing with the findings of Hamada et al.14 Meanwhile, when watching electronic album and relevant generic videos, the elderly people continually communicated their views or asked us about what was shown on the screen. Finally, the elderly people discussed their interests and asked us to add more content or extend screening, making the whole activity more active and easy and promoting interaction among elderly people with MCI and with researchers. This study also acknowledges the following limitations. First, owing to schedule of rest and recreational activities, this study featured nonuniform time of data collection and evaluation. Weaker intervention effects ORCID Huan‐huan Zhang http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4491-9935 RE FE RE NC ES 1. Prince M, Imo A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, Wu YT, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2015: the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer's Disease International;2015. 2. Chen H, Huang YQ, Liu ZR, Luo XM. A review of epidemiological studies of Alzheimer. Disabil Res. 2011;2:22‐26. 3. Corbyn Z. New set of Alzheimer's trials focus on prevention. Lancet. 2013;381(9867):614‐615. 4. Tong JF, Guo SY, Tao XJ, et al. The elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment in the community of Tangshan. China J Health Psychol. 2013;21(11):1642‐1644. 5. Jia J, Zhou A, Wei C, et al. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and its etiological subtypes in elderly Chinese. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(4):439. resulted from longer time needed by participants to complete the assessment. Second, this study selected only 1 nursing home in Changchun because of limitation in time, funds, and human resources. Studies rarely explored living in different levels of scale and management of long‐term facilities from Changchun, China, failing to show subsequent effects of long‐term intervention. Finally, tools were insufficient to assess interaction and communication among elderly people with MCI and between researchers and participants of the study. 6. Zhao JF, Wu TF, Han FM, et al. Study on demographic factors of mild cognitive impairment among elderly population in Tianjin community. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2015;19(4):330‐333. 7. Zhao J, Yao L, Wang C, Yun S, Sun Z. The effects of cognitive intervention on cognitive impairments after intensive care unit admission. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2015;27(3):1‐17. 8. Tanaka Y, Nogawa H, Tanaka H. Music therapy with ethnic music for dementia patients. Int J Gerontol. 2012;6(4):247‐257. 622 ZHANG ET AL. 9. Subramaniam P, Woods B, Whitaker C. Life review and life story books for people with mild to moderate dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(3):363‐375. 28. Jia JP, Wang YH, Zhang ZX, et al. Guidelines for dementia and cognitive impairment in China (three): selection of neuropsychological assessment scale. Natl Med J China. 2011;91(11):735‐741. 10. Barban F, Annicchiarico R, Pantelopoulos S, et al. Protecting cognition from aging and Alzheimer's disease: a computerized cognitive training combined with reminiscence therapy. Int J Geriatr Psych. 2015; 31(4):340‐348. 29. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr. 2005;53(4):695‐699. 11. Ghanbarpanah I, Khoshknab MF, Shahbalaghi FM. Effects of 8 weeks (8 sessions) group reminiscence on mild cognitive impaired elders' depression. IJB. 2014;5(4):11‐22. 12. Nakatsuka M, Nakamura K, Hamanosono R, et al. A randomized controlled trial of psychosocial interventions for old‐old people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI): physical and neuropsychological outcomes‐the Kurihara project. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(4):P492. 13. Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: amulti‐center, randomized, controlled, double‐blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;55(2):787. 14. Hamada T, Kuwahara N, Morimoto K, Yasuda K, Akira U, Abe S. Preliminary study on remote assistance for people with dementia at home by using multi‐media contents. Berlin:Springer. 2009;5614: 236‐244. 15. Yasuda K, Kuwabara K, Kuwahara N, Abe S, Tetsutani N. Effectiveness of personalised reminiscence photo videos for individuals with dementia. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2009;19(4):603‐619. 16. Yasuda K, Kuwahara N, Kuwabara K, Morimoto K, Tetsutani N. Daily assistance for individuals with dementia via videophone. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(5):508‐516. 17. Boulay M, Benveniste S, Boespflug S, Jouvelot P, Rigaud AS. A pilot usability study of MINWii, a music therapy game for demented patients. Technol Health Care. 2011;19(4):233‐246. 18. Benveniste S, Jouvelot P, Péquignot R. The MINWii project: renarcissization of patients suffering from Alzheimer's disease through video game‐based music therapy. EntertainmentComputing ‐ ICEC 2010 9th. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2010;6243(4):79–90. http:// www.cri.ensmp.fr/classement/doc/A‐417.pdf 19. Benveniste S, Jouvelot P, Pin B, et al. The MINWii project: renarcissization of patients suffering from Alzheimer's disease through video game‐based music therapy. Ent Comput. 2012; 3(4):111‐120. 20. Alm N, Dye R, Gowans G, Campbell J, Astell A, Ellis M. A communication support system for older people with dementia. Computer. 2007; 40(5):35‐41. 21. Purves BA, Phinney A, Hulko W, Puurveen G, Astell AJ. Developing CIRCA‐BC and exploring the role of the computer as a third participant in conversation. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;30(1):101‐107. 30. Chen H, Yu H, Kong LL, et al. Reliability and validity of Beijing version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment in the elderly people residing in Qingdao. Int J Geriatr. 2015;36(5):202‐205. 31. Sun YR, An C, He W, Zhu YZ, Liu Y, et al. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2012;21(10):948‐950. 32. Zhang XQ. The application of Montreal Cognitive Assessment in screening of mild cognitive impairment among the elderly in Changsha city. Changsha:Central South University. 2013. 33. Zhang LX, Liu XQ. Determination of the cut‐off point of the Chinese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Chinese elderly in Guangzhou. Chin Ment Health J. 2008;22(2): 123‐125, 151. 34. Hachinski V, Iadecola C, Petersen RC, et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke‐Canadian Stroke Network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards. Stroke. 2006;37(9): 2220‐2241. 35. Chertkow H, Nasreddine Z, Joanette Y, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment, no dementia: part A, concept and diagnosis. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(4):266‐282. 36. Davis BH, Shenk D. Beyond reminiscence using generic video to elicit conversational language. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014; 30(1):61‐68. 37. O'Rourke J, Tobin F, O'Callaghan S, Sowman R, Collins DR. ‘YouTube’: a useful tool for reminiscence therapy in dementia? Age Ageing. 2011;40(6):742‐744. 38. Machulda MM, Pankratz VS, Christianson TJ, et al. Practice effects and longitudinal cognitive change in normal aging vs incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia in the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;27(8):1247‐1264. 39. Gavett BE, Gurnani AS, Saurman JL, et al. Practice effects on story memory and list learning tests in the neuropsychological assessment of older adults. Plos One. 2016;11(10): e0164492. 40. Jin Y, Ni QN, Wu T. Temporal and spatial disorientation in patients with Alzhelmer's and mild cognitive impairment. Prev Treat Cardio‐Cerebral‐ Vascular Dis. 2010;10(2):95‐96. 41. Luo X, Schmeidler J, Rapp MA, et al. The MMSE orientation for time domain is a strong predictor of subsequent cognitive decline in the elderly‐Guerrero‐Berroa‐2009‐International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry‐Wiley Online Library. Int J Gaeriatr Psych. 2009; 24(12):1429‐1437. 22. Cohen‐Mansfield J, Golander H. The measurement of psychosis in dementia: a comparison of assessment tools. Alz Dis Assoc Dis. 2011; 25(2):101‐108. 42. Weiss EM, Papousek I, Fink A, Matt T, Marksteiner J, Deisenhammer EA. Quality of life in mild cognitive impairment, patients with different stages of Alzheimer disease and healthy control subjects. Neuropsychiatr. 2012;26(2):72‐77. 23. Smith ER, Broughton M, Baker R, et al. Memory and communication support in dementia: research‐based strategies for caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(02):256‐263. 43. Deng LL. The effect of structured comprehensive cognitive intervention on community‐ dwelling elderly people with mild cognitive impairment. Chongqing:Third Military Medical University;2014. 24. Broughton M, Smith ER, Baker R, et al. Evaluation of a caregiver education program to support memory and communication in dementia: a controlled pretest–posttest study with nursing home staff. Int J of Nurs Stud. 2011;48(11):1436‐1444. 44. Gaggioli A, Scaratti C, Morganti L, et al. Effectiveness of group reminiscence for improving wellbeing of institutionalized elderly adults: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):1‐6. 25. Chao HC, Kaas M, Su YH, Lin MF, Huang MC, Wang JJ. Effects of the advanced innovative internet‐based communication education program on promoting communication between nurses and patients with dementia. J Nurs Res. 2016;24(2):163‐172. 26. Lewis ML, Hobday JV, Hepburn KW. Internet‐based program for dementia caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;25(8):674‐679. 27. Wang QY. Study on the Effect of Art Therapy in Elderly with Mild Cognitive Impairment under the Theme of Reminiscence. Hangzhou: Hangzhou NormalUniversity; 2016. How to cite this article: Zhang H, Liu P, Ying J, et al. Evaluation of MESSAGE communication strategy combined with group reminiscence therapy on elders with mild cognitive impairment in long‐term care facilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:613–622. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4822