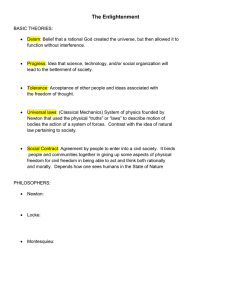

John Locke 1632-1704 John Locke was born on August 29, 1632, in Wrington, Somerset, England. Regarded as one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers, he was known as the Father of Classical Liberalism. He was an economist, political operative, physician, Oxford scholar, and medical researcher as well as one of the great philosophers of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Locke created the philosophy that there was no legitimate government under the Divine Right of King's theory, which emphasized that God chose some people to rule on earth in His will. Therefore, the monarch's actions were the will of God and to criticize the ruler meant you were challenging God. However, Locke did not believe in this theory and wrote his own to challenge it. Locke's writings also greatly influenced the founding fathers of the United States when writing the Constitution. They implemented his idea that the power to govern was obtained from the permission of the people. He believed the purpose of government was to protect the natural rights of its citizens. He stated that natural rights were life, liberty, and property and that all people automatically earned these simply by being born. When a government did not protect those rights, the citizen had the right to overthrow the government. These ideas were incorporated into the Declaration of Independence by Thomas Jefferson. Once they took root in North America, the philosophy was adopted in other places as justification for revolution. Locke believed that children are born with their minds a blank sheet of paper, a clean slate, a tabula rasa. He also maintained that children are potentially free and rational beings and that the realization of these human qualities tends to be disillusioned through the imposition of the sort of prejudice that perpetuates oppression and fallacy. Locke believed it was the upbringing and education that hindered the development of children's humanity. Locke noted two consequences of the doctrine of the tabula rasa: egalitarianism and vulnerability. Locke believed the purpose of education was to produce an individual with a sound mind in a sound body to better serve his country. Locke thought that the content of education ought to depend upon one's station in life. The common man only required moral, social, and vocational knowledge. He could do quite well with the Bible and a highly developed vocational skill that would serve to support him in life and offer social service to others. However, the education of gentlemen ought to be of the very highest quality. The gentleman must serve his country in a position of leadership. For gentlemen, Locke believed that he must have a thorough knowledge of his language. The schools of the Puritans in England broke with tradition completely. They sought to educate one for the society in which he would live. The schools were called, therefore, schools of social realism. Locke, in keeping with Milton and other Puritans, held that the content of the curriculum must serve some practical end. He recommended the introduction of contemporary foreign languages, history, geography, economics, math, and science. Locke proposed the following for the education of the gentleman: a. Moral Training. All Christians must learn to live virtuously. b. Good Breeding. The gentleman must develop the poise, control and outward behavior of excellent manners. Education must aim, therefore, at developing correct social skills. c. Wisdom. The gentleman ought to be able to apply intellectual and moral knowledge in governing his practical affairs. d. Useful Knowledge. The gentleman must receive an education which will lead to a successful life in the practical affairs of the society, as well as that which leads to the satisfaction derived from scholarship and good books. In his final years, he lived in the country at Oates in Essex at the home of Sir Francis and Lady Masham. Before his death, Locke saw four more editions of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. He died at Oates in Essex on October 28, 1704. To summarize, Locke’s Big Ideas are the following; he coined the term tabula rasa (blank slate) to denote that the human mind is born unformed and that ideas and rules are only enforced through experience thereafter; he established the method of introspection, focusing on one’s own emotions and behaviors in search of a better understanding of the self; and argued that in order to be true, something must be capable of repeated testing, a view that girded his ideology with the intent of scientific rigor. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) Jean Jacques Rousseau was an 18th-century philosopher who later became known as a revolutionary philosopher on education and a forerunner of Romanticism. One of the most influential thinkers during the Enlightenment in 18th century Europe, his ideas concerning education and the role society plays in a child's development/education was published in his famous work Emile, which caused some sparks to help light the French Revolution and eventually brought about his exile from Paris. Born in Geneva on June 28th, 1712, Rousseau's ultimate belief was that people are born good, but are corrupted by society. He also thought that individuals only learn these "bad habits" by living in the city, which is why he preferred a rural setting for children to learn. He wanted to abandon society's hypocrisy and pretentiousness. He believed that natural education promotes and encourages qualities such as happiness, spontaneity, and the inquisitiveness associated with childhood. He wanted children to be shielded from societal pressures and influences so that the natural tendencies of each child could emerge and grow without any unwarranted corruption. Rousseau's greatest work was Émile, published in 1762. More a tract upon education with the appearance of a story than it is a novel, the book describes the ideal education which prepares Emile and Sophie for their eventual marriage. Book One deals with the infancy of the child. The underlying thesis of all Rousseau's writings stresses the natural goodness of man. It is a society that corrupts and makes man evil. Rousseau states that the tutor can only stand by at this period of the child's development, ensuring that the child does not acquire any bad habits. Rousseau condemned the practice of some mothers who sent their infants to a wet nurse. He believed it was essential for mothers to nurse their children. This practice is consistent with natural law. According to Rousseau’s Émile Book Two, the purpose of education consisted of the tutor preparing the child for no particular social institution, but to preserve the child from the baleful influence of society. Emile is educated away from city or town; living in the country close to nature should allow him to develop into a benevolent, good adult. The child learns by using his senses in direct experience. He lives in Spartan simplicity. Book Three describes the intellectual education of Emile. Again, this education is based upon Emile's nature. When he is ready to learn and is interested in language, geography, history, and science, he will possess the inner direction necessary to learn. This learning would grow out of the child's activities. He will learn languages naturally through normal conversational activity. Rousseau assumes that Emile's motivation leads to the purposive self-discipline necessary to acquire knowledge. Finally, Emile is taught the trade of carpentry to prepare him for an occupation in life. Book Four describes the social education and the religious education of Emile. The education of Sophie is considered and the book concludes with the marriage of Emile and Sophie. Emile is permitted to mingle with people in society at the age of 16. He is guided toward the desirable attitudes that lead to self-respect. Emile's earlier education protects him from the corrupting influence of society. The revelation and dogma of organized religion are unnecessary for man. The fundamental tenets of any religion affirm the existence of God and the immortality of the soul and these are known through the heart only. Having completed the explanation of Emile's ideal education, Rousseau turns his attention to the education of Sophie. Women are not educated as are men. The natural purpose of a woman is to please a man. She is expected to have and care for children, and to please, advise and console her husband whenever necessary. Her education does not extend beyond this purpose. His views of monarchy and governmental institutions outraged the powers that be and his ideas on natural religion, unorthodox to both Catholics and Protestants, forced him to flee to Môtiers in Neuchâtel under the protection of Frederick the Great. There Rousseau studied botany and eventually accepted David Hume's invitation to settle in England where he wrote most of his autobiographical Confessions. Rousseau's philosophical ideas on the education of children were very risqué and created quite the uproar. His philosophy was also not gender-neutral. Rousseau believed females were to be educated to be governed by their husbands. They were to be weak and passive, brought up in ignorance and meant to do housework. Males were to be educated to be self-governed, and the philosophies in Emile essentially only pertained to males in society. He believed that the private sphere depended on the naturalized subordination of women for both it and the public political sphere to function. Ironically, one of his main beliefs in Emile that would not have been scandalous in Rousseau's day would be seen as sexist in today's society. Rousseau's powerful influence on the European Romantic movement and after was due to his vision of a regenerated human nature. His philosophy revealed a striking combination of idealistic and realistic elements that constantly seemed to open the possibility of a better world. This optimistic outlook was transmitted through a particularly eloquent and persuasive style, rich in emotional and musical overtones, giving the impression of intense sincerity. Rousseau's great challenge was to convince the humblest of men that they should never feel ashamed to call themselves human beings. Rousseau ultimately left the city of Paris to live in the country. He had become completely disillusioned with the norms of society in the city, especially that of the monarchy, and had even become disgusted with his friends. He felt that children more fully learned right and wrong by experiencing the consequences of their actions firsthand rather than being physically punished as most people in his day did. Rousseau firmly believed that nature is kind and man essentially is not; humans have the potential to be kind, but oftentimes choose not to. Seeking shelter in a hospital, Rousseau eventually died insane in a cottage at Ermenonville, July 2, 1778, from a sudden attack of thrombosis, which aroused suspicions of suicide. He was buried there until 1794 when his remains were placed with Voltaire's in the Panthéon in Paris.