Negotiating

bits with Models:

The Power of Expertise

Tarald Laudal Berge

yvind Stianseny

September 4, 2017

Abstract

The international investment regime is in ux. As a reaction to the growth of treatybased claims for investment arbitration, awareness around the content of investment

treaties has risen. Some states have chosen to exit the regime altogether, some have

started re-negotiating their treaties, while many states are still engaged in signing new

investment treaties. At the same time a legitimacy debate has arisen in academia. One

of the central questions in the debate is: Who are the rule-makers, and who are the

rule-takers in the investment regime? Building on ndings from qualitative research

and theory of deliberation and arguing, we make the case for how success in investment

treaty negotiations is more likely to stem from expertise in states' negotiating bodies

than rational choice assumptions around material assets. In our empirical analysis, we

use novel text-as-data analysis to leverage states' model investment treaties as ideal

type treaty preference measures. When comparing the textual distance between a

large sample of model treaties and treaties concluded on the basis of models, we nd

that states with governance systems that increase negotiation expertise are the most

successful in investment treaty negotiations. Our theoretical approach should be of

interest to other scholars, and our empirical ndings have signi cant implications for

how policy-makers should think about power in economic diplomacy.

y

Dept. of Political Science and PluriCourts, University of Oslo. E-mail: t.l.berge@stv.uio.no.

Dept. of Political Science and PluriCourts, University of Oslo. E-mail: oyvind.stiansen@stv.uio.no.

1

1

Introduction

Based on bilateral investment treaties (bits) and preferential trade agreements (ptas),

investors have now led close to 900 known claims for reparation under investment treaty

arbitration (ita).1 Most of the claims have been brought the last 15 years, and the claims

have spurred allegations of non-egalitarian power structures in the underlying treaties. As

some states have started a full edged retreat from the regime altogether, and others have

initiated extensive e orts to re-negotiating their existing investment treaties (Berge and

Hveem 2017), a vociferous academic debate around the legitimacy of the regime has come

about (see e.g. Ma 2012, Waibel et al. 2010).2 One of the core questions of this legitimacy

debate is who the rule-makers and the rule-takers are in the investment regime. Some

argue that developing countries are pressured to agree with inappropriate laws under

bits

(Gwynn 2016), while others note that the dynamism and decentralisation of the current

investment regime makes it possible for all governments to negotiate, update and/or modify

their agreements (Pauwelyn 2014). In this paper we therefore ask: What can states do to

a ect the content of investment treaties they sign? What determines success in investment

treaty negotiations?

An age-old puzzle in international negotiations is the structuralists' paradox (Zartman

and Rubin 2002: 3). How is it that presumptively weaker states can gain concessions

when negotiating with more powerful states? Expecting to lose, one would assume that

weaker states would avoid negotiations with powerful states at all costs, and strong parties

would have little need to negotiate with weak parties when they can e ectively take what

they want with force. Yet, weak states not only engage in international negotiations with

stronger states, they often emerge with sizeable gains. This is very much the case in investment treaty negotiations, but the current body of empirical studies still lean heavily on

rationalist accounts of strategic competition and coercive bargaining as drivers of negotiating success (Elkins, Guzman and Simmons 2006, Allee and Peinhardt 2010). In the same

way that rationalist approaches to power-based bargaining has been common in analyses of

more formal international organizations,3 recent studies of power asymmetry in economic

As of August 2017, The PluriCourts Investment Treaty and Arbitration Database (PITAD)(Behn, Berge

and Langford 2017) had 879 treaty-based investor-state arbitrations registered, and the unctad investment

policy hub had 817 cases. See: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org

2 The rise of ita has also spawned a vast literature on the evolution of investment treaty law. See e.g.

Alvarez and Sauvant (2011), Brown and Miles (2011), Echandi and Sauve (2013).

3 See e.g. Drezner (2008) on international regulatory regimes in general, Gruber (2000) on supranational

institutions governing money and trade, and Copelovitch (2010) on the lending practice of the imf.

1

2

diplomacy nd that states' ability to include strong enforcements provisions in bits depend

on economic power (Allee and Peinhardt 2014), that developing states are more likely to tie

their hands under unfavourable bits than developed states (Simmons 2014) and that states'

military power a ects negotiation success (Allee and Lugg 2016).

The qualitative research of Poulsen (2014; 2015), however, concludes that rather than

power asymmetries, what is driving success in

bit

negotiations is knowledge asymmetries.

Negotiating capacity is driven by states' experience and expertise in investment treaty making. This focus on knowledge can be reconciled with ndings concerning the nature of

deliberation in other areas of international negotiation where the importance of negotiating

context is highlighted (Risse 2000; 2004). In this paper we therefore propose a power-asexpertise approach to the study of success in

bit

negotiations. We use insights from the

theory of deliberation and arguing, in conjunction with more traditional negotiation theory

and decision analytic techniques (Schelling 1960, Zartman and Rubin 2002), to inform an

understanding of success in bit negotiations as stemming from negotiation expertise.

In addition to the theoretical innovation, our analysis makes a distinct methodological

advance on previous scholarship. Instead of making treaty preference assumptions based on

a capital-exporter vs. capital-importer dichotomy, we utilize public bargaining drafts called

model

bits

to measure states' ideal type preferences. To generate measures of negotiating

success, we compute the verbatim distance between model

bits

and concluded

bits

with

novel text-as-data methods (Spirling 2012, Alschner and Skougarevskiy 2016a).

Our ndings indicate that there is a robust, positive relationship between negotiation

expertise asymmetries and success in bit-making. Interestingly, we also nd that the e ect

of di erences in material assets such as home markets and domestic investment traction is

less associated with bit outcomes than previously thought.

The article is structured as follows. First, we brie y elaborate on the conventional understanding of what drives success in investment treaty arbitration. Next, we develop our

theory of negotiating power as expertise, and discuss the mechanisms through which expertise drives success. Crucially, we argue that certain institutional capacity characteristics are

likely to generate an environment in which negotiating expertise is likely to ourish. Third,

we expand on our measure of success in bit negotiations, and present our data and estimation methods. Fourth, we present our analysis and a broad range of robustness checks. We

conclude by contextualizing our ndings and discussing what implications they should have

for countries that are engaged in investment treaty negotiations or renegotiations.

3

2

The conventional rationalist account

The bit narrative has changed over the years, and researchers have moved away from studying the e ects of

bits

on foreign direct investment (fdi) { towards studying

bit

and the dynamics of investment treaty bargaining. The standard rationale for

di usion

bits

usu-

ally starts with the fact that multinational investors are subject to hazards when investing

abroad. These hazards decrease expected pro t margins through imposing transaction costs

on operations (Williamson 1985, North 1990). At the same time, with global competition

for capital may lead states to craft business friendly policies to attract investment. This

creates a paradox. Before the investment it might be rational to lure investors with concessions such as tax holidays, regulatory exemptions and special production zones (Kobrin

1987). But after the investment it may be rational for states to renege on those concessions,

creating what is known as the time inconsistency problem. The greater the sunk costs of

the investor, the larger the inconsistency problem becomes (Vernon 1971). The challenge

for the investor is to assess whether states' pre-investment commitments are credible. And

the worse the domestic institutions to protect property in the capital importing country,

the less credible that country's commitment is. Countries trying to attract capital therefore

need some mechanism to exhibit ex ante commitment to property rights protection, and

bits

are often viewed as a credible commitment device t for the purpose.

Almost all existing research on why countries sign

bits

has come to analyse treaty

negotiations in light of this rational choice framework, assuming a simple North-South world

dichotomy (Elkins, Guzman and Simmons 2006, Allee and Peinhardt 2010; 2014, Simmons

2014). At their core, they make ex ante assumptions on three levels. First, they base

their studies on a capital-exporter (developed countries) versus capital-importer (developing

countries) dichotomy. Whereas this dichotomy may have been a fair re ection of reality in

the early days of the regime when North-South bits were predominant, we believe it is less

suited in a world where multinational corporations from developing countries are on the rise

(Sauvant 2009), and both South-South bits (Poulsen 2010) and North-North mega-regional

economic partnerships4 have become commonplace.

Second, the studies derive (static) treaty preferences from this dichotomy. In short, they

assume that treaty content can be mapped along a unidimensional protection- exibility

See for example the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (De Ville and Siles-Brugge 2015),

the Trans-Paci c Partnership (Alschner and Skougarevskiy 2016b) and the Comprehensive Economic and

Trade Agreement between the European Union and Canada (Fafard and Leblond 2013).

4

4

scale, where negotiation success for capital-exporters is when they achieve bits with strong

investor protection,5 and success for capital-importers is maintaining reasonable domestic

regulatory space.6 The degree to which concluded treaties lean more towards either the

protection or the exibility endpoints of this scale depends on the relative degree to which the

two parties depend on the treaty being negotiated.7 The implication is that the party most

dependent on an agreement should be most willing to make concessions in the negotiations,

and each negotiating party's power is thus inversely proportional to the value they place on

reaching an agreement as compared to the best alternative policy option.8

Third, the developing states' treaty dependence is usually assumed to stem from their

dependence on fdi.9 Developed states' treaty dependence on the other hand is assumed to

be shaped by their dependence upon protecting investors abroad { and while fdi is scarce,

the supply of developing country host states with which one can sign

bits

is not. This

creates a dynamic where developing countries, based on continuous assessments of costs

and bene ts, are presumed to engage in rational competition for

fdi

through

bit

signing

(Elkins, Guzman and Simmons 2006: 825).

Research by Poulsen (2014; 2015) however demonstrate that

bit

negotiators in the de-

veloping world have not made their bit decisions based on cost-bene t analyses or rational

competition for capital. Importantly, the rationalist account fails to take into account that

in the absence of issue-speci c expertise and experience, generalist bureaucracies rarely diverge from default solutions when negotiating

bits

(Sunstein 2013). This importance of

possessing expertise in complex, international negotiations has been widely acknowledged

within negotiation theory (Winham 1977, Zartman 1995). The crux of the argument is that

while no negotiator will ever have perfect knowledge of the technical or legal issues at hand,

nor the preferences of other parties to an agreement, those with superior expertise should

As that would relieve them of the potential costs associated with protecting their investors abroad

through diplomatic espousal.

6 As they wish to retain the possibility to adapt industrial regulation and tax policy as their economy

evolves through di erent stages of maturity. See Broude, Haftel and Thompson (2017) for a more recent

discussion of state regulatory space in the context of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.

7 This thinking is based on the notion of asymmetrical interdependence (Keohane and Nye 1977), which, in

the context of intergovernmental negotiations, implies that the distribution of bene ts among the negotiating

parties re ect their relative negotiating power. Power is shaped by patterns of policy interdependence

because getting to an agreement is more important for one negotiating party than the other.

8 This is what is called their preference intensity (Moravcsik 1998: 60-62). Preference intensity in international negotiations is often viewed under the umbrella of issue-speci c power. See for example Tallberg

(2008: 692) on bargaining in the European Council.

9 Which in turn is based on an assumption that bits will attract fdi, a causal relationship around

which there is little empirical consensus. For a reviews of investor surveys, see: Poulsen (2015: 8). For

empirical studies, see: Hallward-Driemeier (2003), Egger and Pfa ermayr (2004), Neumayer and Spess

(2005), Salacuse and Sullivan (2005), Kerner (2009), Aisbett (2009).

5

5

be better positioned to shape agreements in their own favour (Young 1991, Tallberg 2006).

This analysis is an attempt at testing Poulsen's qualitative ndings in a larger sample of

negotiations, while building a broader theory of the power of expertise in bit negotiations.

3

Negotiating expertise as a success factor

Our theory of what drives success in

bit

negotiations departs from theory of deliberation

and arguing (Risse 2000; 2004). This theory states that the modes of rule-setting in international negotiations can be organized along a continuum with two endpoints: arguing

and bargaining. Bargaining follows the logic of rational choice theory, and is a form of

rule-setting where self-interested, utility-maximising actors negotiate agreements based on

give-and-take of ex ante xed preferences.10 In this context, previous hierarchies of power

carry substantial weight. Arguing, and the closely related concept of persuasion, pertain to

a social logic quite di erent from that theorized by rational choice. When arguing, actors

instead try to challenge the validity of claims in normative or causal statements through

communicative consensus-building. Actors that use arguing instead of bargaining, make

themselves open to being persuaded by the better argument, making previously important

social and power hierarchies less decisive for the outcome.

Importantly, when analysing the dynamics of international negotiations, deliberation

theory holds that we should start by identifying the context in which the negotiations take

place. In short, all negotiations are embedded in a material and a social context. Features

of the material context are typically the material assets of the participants (money and

military strength), their cost-bene t calculations, and the various tangible factors that may

heighten the credibility of commitments or make side payments possible (Schoppa 1999).

The key feature of the social context on the other hand is the institutional setting in which

negotiations take place.11 Two points are important in this regard. First, if the context

in which negotiations take place is densely institutionalized, with agreed-upon norms, rules

and decisions-making procedures to guide the process, a strong `logic of appropriateness' is

likely to prevail (March and Olsen 1998: 951-952). This logic restricts negotiators' room

10 This logic of bargaining analogous to the view of political order as stemming from a `logic of expected

consequences,' where order arises \from negotiation among rational actors pursuing personal preferences

or interests in circumstances where there may be gains to collective action" (March and Olsen 1998: 949).

Coordination is, in this view, dependent upon the bargaining position of the actors.

11 The idea that inter-state negotiations in fact take the form of social encounters has been widely recognised within many of the social sciences. See for example Kramer and Messick (1995) for a broad theory of

negotiation as a social process.

6

for exibility through determining which arguments and justi cations are seen as socially

acceptable. Second, the degree to which negotiations are mediated by an external authority

or audience should also a ect the negotiation dynamics. If negotiations take place in front

of an audience they are likely to take a ritualistic form where negotiators remain true to

their mandate and pre-negotiation positions, whilst negotiators are more likely to exhibit

exibility and seek consensus if the negotiations take place behind closed doors. This is

because the negotiators face less risk of being called out by relevant stakeholders when

exposing their states' interests to arguments and compromise.

While both the material and the social context is important, Ulbert and Risse (2005)

show that studies of international negotiations have tended to focus overwhelmingly on the

material side. This is also true in the eld of

bit

studies, as discussed above. Most studies

focus exclusively on material context factors such as market size, coercive capabilities and

the utility-maximising way in which states leverage their material assets. As such, the

studies assume bargaining to be the chief strategy sought by states when negotiating bits.

However, when we explore the social context of

bit

negotiations, there are good reasons to

believe that arguing plays an important role too.

First,

negotiations do not usually happen under the auspices of any particular international or intergovernmental organization.12 Quite the contrary, bit negotiations have

bit

largely taken place on an ad-hoc basis, often in conjuncture with other interstate negotiations. Secondly, until Lauge Poulsen (2014; 2015) started his seminal project on

bits

the developing world a few years ago, we had very few rst hand accounts of how

bit

in

ne-

gotiations transpired, simply because they were all negotiated behind closed doors. What

we knew came from unctad:

bit

negotiations usually entail several rounds of discussions,

the exchange of drafts and counter-drafts, and face-to-face negotiations around particularly

dicult provisions. Ultimately, bits are negotiated in a setting where there should be ample

room for exibility, compromise, argumentation and persuasion. As highlighted by

tad,

unc-

\the key point to be stressed is that each [bit] negotiation is a unique and peculiar

process requiring exibility and accommodation" (1998: 28). Following the theory of deliberation and arguing outlined above, one can therefore assume that the degree to which

states' negotiators are skilled in normative and causal arguing should have an in uence on

their success in bit negotiations.

The only exception being the bit signing ceremonies unctad hosted in the late 1990's and early 2000's.

However, the organization itself did not participate in, or oversee, the individual negotiations { they only

facilitated them (Poulsen 2015: 91-99).

12

7

Before we expand on our theory, it should be noted that pure arguing and pure bargaining represent opposite ends of a continuum, and that the communicative processes adopted

in most international negotiations are hybrids forms that reside somewhere along this continuum. In other words, the importance we place on social context should not be confused

with the claim that arguing always is of most importance to nal outcomes. Instead, material assets and negotiating expertise seem to be important at di erent stages of a treaty

negotiating processes. Empirical research does for example seem to suggest that negotiating expertise is particularly relevant during the agenda-setting and pre-negotiation phases,

where the initial frame for the negotiations are set. Arguing also seem to be of particular

importance when negotiations break down or reach stalemates, because arguing may allow

actors to re-re ect about their stance and interests (Risse 2004: 302-303).

Material assets on the other hand, seem to be of special importance during the prenegotiation phase. A case study of the 1987 negotiations on the United States-Canada

fta,13 illustrates this dynamic very well (Winham and DeBoer-Ashworth 2002). Canada

entered the negotiations with an interest in establishing a rule-based (rather than powerbased) relationship with the United States. They viewed a strong dispute settlement mechanism in the treaty as a way to achieve this. And surprisingly to commentators at the time

they achieved just that, in spite of their material inferiority. In Chapter 19 of the treaty

the parties agreed to replace judicial review by national courts in cases of anti-dumping and

countervailing with bi-national panel reviews. In their analysis of the negotiations, Winham

and DeBoer-Ashworth note that the United States appeared to leverage its superior material

resources to encourage Canada to participate in the negotiations. But once the negotiations

actually began \a threshold was crossed in which a perceived asymmetric economic-power

relationship did not automatically translate into an asymmetric negotiating-power relationship" (2002: 48).

3.1

Decision analytics and expertise

An adapted version of Schelling's (1960: 47-51) binary choice diagram can be used to

illustrate the mechanism through which parties' negotiating expertise a ects outcomes in bit

negotiations.14 In this scheme, one party exercises negotiating power vis-a-vis its counterpart

when its actions negatively or positively alter their (perceived) valuation of a particular

13

14

The 1987 US-Canada fta was the North American Free Trade Agreement (nafta) forerunner.

Adapted by Zartman and Rubin (2002: 11-12).

8

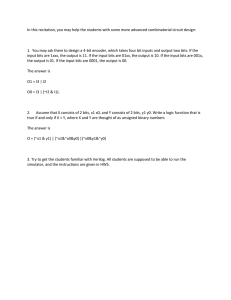

CountryA 's output value

r

r

0

0

s

s

CountryB 's output value

Figure 1: From pre-negotiation to post-negotiation perceptions of value

outcome; for example the wording of a

bit

provision. While rational materialists such

as Schelling viewed credible threats and side payments as the most important bargaining

tactics, deliberation theory assumes that the ability to make causal and normative arguments

{ what we label negotiating expertise { is the chief mechanism through which bit negotiators

obtain gains in international negotiations (Risse 2004: 297).

So for the purpose of our study, consider the following example: Country and Country

A

are negotiating a

bit

B

(see Figure 1). After they have swapped opening drafts or pre-

negotiation policy preferences, they establish a draft document with contentious provisions

and formulations in brackets. One of these is the transfer of funds provision.15 Because

Country is worried about depletion of its foreign currency reserves, it wishes to maintain

A

the right to impose some level of exchange controls on foreign investors. Country however

B

is more worried about its outgoing investors' right to transfer investments and returns into

freely convertible currencies. Let Country 's pre-negotiation transfer of funds preference

A

be connoted by

r

and Country 's preference connoted by s. The two countries' perceived

B

output valuations of preferences r and s are mapped along the y- and x-axes.

As negotiations on how to solve the con icting considerations evolve, both negotiators

try to argue in favour of their speci c perception of the ideal transfer of funds provision.

In e ect, they try to convince their counterpart that his or her pre-negotiation valuation is

wrong. Country 's negotiator may for example manage to reassure Country 's negotiator

B

A

Most bits include a provision guaranteeing free transferability of investment-related payments (Vandevelde 2010: 316-324). This is however a notoriously dicult provision to negotiate (Vandevelde 1998: 632).

For example, the negotiators in the 2004 us-Chile fta spent nearly two years negotiating back and forth

before they found a version both parties could accept (Ffrench-Davis et al. 2015: 335-336).

15

9

that concerns over foreign currency depletion are overwrought, while also making the case for

why free transfer of funds will be conducive to inward investment in the future. If, through

this interaction, Country 's negotiator negatively alter Country 's perceived valuation of

exchange controls (from r to r0 ), at the same time as positively altering Country 's perceived

valuation of free transfer of funds (from s to s0 ), the parties should agree on a transfer of funds

B

A

A

provision that is more in line with Country 's pre-negotiation preferences than Country 's.

B

A

As such, Country has used its superior negotiating expertise vis-a-vis Country to achieve

B

A

a more favourable outcome for itself.

3.2

Institutional capacity and negotiating expertise

In the absence of data on states' actual treaty negotiators (which would be our direct dependent variable), we propose an indirect approach to thinking about negotiating expertise.

Our general claim is that higher levels of institutional capacity should produce an environment more conducive to generating expertise in the civil service. Institutional capacity

is de ned as the potential capabilities of bureaucratic institutions to make and implement

policy, independent of partisan and ideological policy preferences (Krause and Woods 2014:

370). As such, it is analogous to Teorell and Rothstein's (2008) approach to quality of

government as driven by impartiality. They focus on how the implementation of policies by

civil servants should happen without having to take into consideration interest that are not

beforehand stipulated in the policy or the law.

In line with this thinking, our speci c claim is that where bureaucrats are insulated from

executive or private interest capture, institutional systems that are conducive to the generation and maintenance of expertise are more likely to emerge. And when negotiators are

selected from an expert bureaucracy, they should be better at making causal and normative

arguments. Thus, because states usually select their negotiators from the civil service, we

believe that bureaucratic capacity is the factor most important for fostering negotiating

expertise. However, we believe that public sector corruption, a particularly harmful trait of

bureaucracies, should be considered as well. We discuss these two factors in turn.

Bureaucratic capacity

The reasons for why we believe that impartial bureaucracies are better at generating and

maintaining expertise than impartial ones is grounded in the `Weberian state hypothesis'

10

(Evans 1995). The key institutional characteristics of a `Weberian' bureaucracy include

meritocratic recruitment; civil service procedures for hiring and ring; and lling of higher

levels of the hierarchy through internal promotion. While merits-based hiring16 and civil

service procedures for hiring and ring, are processes that in and of themselves makes entry

and exit in the bureaucracy a question of expertise, the fact that civil servants enter the

bureaucracy based on their merit also make it more likely that e ective performance and

skill-enhancement becomes valued attributes among colleagues (Rauch and Evans 2000: 5052). Indeed, multiple studies have found meritocratic stang of bureaucracies to increase

competence (Krause, Lewis and Douglas 2006, Lewis 2007; 2010, Gallo and Lewis 2011).

In turn, the long-term career rewards that a system of internal promotion generates should

improve intra-bureaucracy communication and information-sharing, and reinforce civil servants' commitment to the job. In the absence of formal merits, civil servants main nevertheless develop expertise through experience and feedback (Neale and Bazerman 1991: 86-87).

As such, structures that ensure stability should also be an aspect on bureaucratic capacity

is assessed.17 ikewise, low levels of turnover should enhance the institutional memory-role

played by the bureaucracy.18

Public sector corruption

There are a couple of reasons for why we believe levels of public sector corruption is also

connected to expertise in states' bureaucracies, but the basic idea is that corruption run

directly counter to the fundamental ideas of meritocracy. Public sector corruption involves

using ones public position to achieve private gain, and is a violation of impartiality through

discriminatory exercise of power (Kurer 2005: 230). In the `tollboth' theory of corruption,

Shleifer and Vishny (1993) suggest that in states that are plagued by corruption, the red

tape regulation that corrupt civil servants and politicians set up to extract bribes lead to

very inecient governance procedures.19 This very ineciency may stop the best people

from being hired, and keep incompetent personnel in the administration. Moreover, a key

manifestation of public corruption is the creation of patronage classes, which in turn politicises and a ects hiring procedures in the civil service system. This feat has for example been

That is, conditioning hiring on a civil service exam or university degree.

See e.g. Weyland's (2006) study of policy reform in Latin America, quoted in Poulsen (2015: 29). The

same argument is made in the context of trade negotiations (Busch, Reinhardt and Sha er 2009).

18 This institutional memory-argument has also been made in the context of legislative turnover (Krause

and Woods 2014: 372).

19 Their theory is empirically corroborated by Djankov et al. (2002).

16

17

11

found to hinder the development of bureaucratic expertise and competent administration in

countries like Spain, Italy, Greece and Portugal (Sotiropoulos 2004).

Before we go on to discuss our data and empirical analysis, it should be noted that the

e ect of institutional capacity on success in

bit

negotiations may also function through

the more conventional credible commitments mechanism. Bureaucracies, to the degree that

they are impartial, function as shock absorbers that minimize the (immediate) e ect of

sudden changes of opinion in the executive oce. Thus, an impartial bureaucracy probably

provides a more ecient and stable negotiating climate for bit negotiators than politicised

bureaucracies. This is important because we know that bit negotiations can be lengthy

procedures,20 and a state's credibility over time may impact its success in negotiations.

4

Research Design

In this section we rst discuss how states' model

bits

are good measures of treaty prefer-

ences, and how a comparison of model bits and concluded bits gives us a valid measure of

relative negotiating success. Next, we present a set of indicators that capture the institutional capacities we believe drive negotiating expertise at the state level, before we present

our control variables and our choice of model speci cation.

4.1

Measuring negotiation success with model BITs

bits

are essentially agreements that set reciprocal terms and conditions for investment between pairs of states, and potential dispute-resolution mechanisms.21 Although bits appear

largely similar when assessed at face value, there are \signi cant di erences concerning

their substantive details" (UNCTAD 2006: xi). Moreover, there are huge di erences in

the relative coherence within states' treaty networks, which is indicative of a fundamental

asymmetry in BIT negotiations (Alschner and Skougarevskiy 2016a).22

The us-China bit negotiations has for example been under way since 2008, and are at the time of

writing still not concluded (Hufbauer, Miner and Moran 2015).

21 bits cover the following areas: de nition of investor and investment (who is protected), admission and

establishment (when is protection given), expropriation (lawfulness and compensation), standards of protection (absolute and relative rights), and investor-state dispute settlement (adjudication and enforcement).

For a more thorough review of the structure of bits, see Dolzer and Schreuer (2008) and Vandevelde (2010).

22 See also the Alschner and Skougarevskiy's Mapping bits website, where the internal consistency of

states' bit networks over time can be explored: http://mappinginvestmenttreaties.com.

20

12

Available model BIT

No available model BIT

Figure 2: Countries with publicly available model bits

An interesting trait of

available. Model

bits

bit

negotiations is that many states make model

are essentially states' starting point when entering

bits

bit

publicly

negotiations

(Brown 2013: 2). Models may be prepared by one or both parties to a negotiation, and the

use of models has proved to be ecient when developing extensive bit networks.23 The use

of model

bits

is also widespread; developed economies such as Switzerland, Netherlands,

Germany, United Kingdom and the United States use them; transition economies like India,

Turkey and Malaysia use them; and developing economies such as Benin, Burkina Faso and

Uganda use them (see Figure 2).

The fact that model

bits

are made public is interesting. Given the high stakes and

general degree of secrecy in economic diplomacy, it would perhaps have been more rational

Big bit signers such as Germany (Dolzer and Kim 2013), Switzerland (Schmid 2013) and China (Shan

and Gallagher 2013) all use model bits when negotiating investment treaties. As of 2013, Germany had

signed 139 bits (of which 130 were in force), Switzerland had signed 130 (116 in force), and China had

signed 130 (101 in force).

23

13

to keep preferences undisclosed. But in practice, the use of model

bits

serve multiple

functions. They facilitate the negotiations around the legal content of treaties, whilst at

the same time reducing drafting and negotiation costs for countries involved.24 The bottom

line is that model

bits

represent, \inter alia, an expression of a states' investment policy,

[and] its negotiation position on the protection of foreign investment" (Brown 2013: 2).25

As such, model bits should represent a more direct expression of state preferences than the

exibility vs. protection assumptions derived from a North-South dichotomy.

The rst step of our research was therefore to gather all model bits we could nd. We

identi ed 92 model texts in total, 90 of which we have a con rmed year of commenced use

on. Most of the texts were downloaded from unctad's Investment Policy Hub.26 We also

identi ed 25 additional texts in various book volumes (Dolzer and Stevens 1995, Dolzer and

Schreuer 2008; 2012, Gallagher and Shen 2009, Brown 2013), some from unctad's old international investment instrument compendiums27 or through direct contact with academics

and ministries in relevant countries.28 Of the 90 models in our dated sample, only 70 model

texts are matched against concluded

bits.

Thus, 20 models were dropped either because

they were shelved, or because we have no available concluded bit to match it against.29

Next, we downloaded all texts of concluded

bits

that are available through

unctad's

Investment Policy Hub, and transformed concluded and model bit pdfs to clean text les

with optical recognition software. To measure the degree of negotiation success, we correlate the verbatim of model bits with bits concluded on the basis of the model.30 We

follow Spirling (2012) and Alschner and Skougarevskiy (2016a) in using an unsupervised

measurement approach based on dividing each text into 5-character substrings (5-grams )

and calculating the similarity between the sets of 5-grams. This yields the dyad-speci c

Jaccard similarity coecient, which is de ned as the size of the intersection between the

two sets of 5-grams divided by the union of the sets of 5-grams. Denoting the 5-gram for

For governments using them, model bits may also contribute to achieving uniformity across ones treaty

universe, as has been demonstrated in the development of the United States' bit program (Schill 2009: 91).

25 This does not mean that model bits are states ideal type preferences. Models are most likely \live"

documents that negotiators continuously amend. We address this measurement error in Section 4.3 and 4.4.

26 See: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org.

27 See:

http://unctad.org/en/Pages/DIAE/DIAE\%20Publications\%20-\%20Bibliographic\

%20Index/International-Investment-Instruments-A-Compendium.aspx

28 A full list of where each model bit was obtained is on record with the authors.

29 Table A1 in the Appendix lists all model texts used in our analysis, and the number of concluded bits

matched per model bit.

30 We use the date of signature to identify which model bit to match concluded bits against. However,

where it is obvious that bits have been concluded on the basis of earlier models (as negotiations may be

lengthy), we swap the match to the former model.

24

14

Similarity

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

1979_netherlands

1984_china

1986_switzerland

1987(I)_netherlands

1989_china

1991_denmark

1991_germany

1991_uk

1993_czech_republic

1993_netherlands

1994_austria

1994_chile

1994_china

1994_us

1995_egypt

1995_hongkong

1995_indonesia

1995_jamaica

1995_srilanka

1995_switzerland

1997_china

1997_netherlands

1998_cambodia

1998_croatia

1998_germany

1998_malaysia

1998_mongolia

1998_southafrica

1998_us

2000_denmark

2000_peru

2000_turkey

2001_finland

2001_greece

2001_iran

2001_korea

2001_russia

2002_austria

2002_belgium

2002_sweden

2002_thailand

2003_canada

2003_china

2003_ghana

2003_india

2003_israel

2003_italy

2003_kenya

2003_uganda

2004_netherlands

2004_romania

2004_us

2005_germany

2005_uk

2006_france

2007_colombia

2007_norway

2008_austria

2008_colombia

2008_germany

2008_ghana

2008_mexico

2008_uk

2009_colombia

2009_macedonia

2009_turkey

2012_usa

2014_serbia

2015_brazil

2015_india

2016_azerbaijan

Model2

2016_azerbaijan

2015_india

2015_brazil

2014_serbia

2012_usa

2009_turkey

2009_macedonia

2009_colombia

2008_uk

2008_mexico

2008_ghana

2008_germany

2008_colombia

2008_austria

2007_norway

2007_colombia

2006_france

2005_uk

2005_germany

2004_us

2004_romania

2004_netherlands

2003_uganda

2003_kenya

2003_italy

2003_israel

2003_india

2003_ghana

2003_china

2003_canada

2002_thailand

2002_sweden

2002_belgium

2002_austria

2001_russia

2001_korea

2001_iran

2001_greece

2001_finland

2000_turkey

2000_peru

2000_denmark

1998_us

1998_southafrica

1998_mongolia

1998_malaysia

1998_germany

1998_croatia

1998_cambodia

1997_netherlands

1997_china

1995_switzerland

1995_srilanka

1995_jamaica

1995_indonesia

1995_hongkong

1995_egypt

1994_us

1994_china

1994_chile

1994_austria

1993_netherlands

1993_czech_republic

1991_uk

1991_germany

1991_denmark

1989_china

1987(I)_netherlands

1986_switzerland

1984_china

1979_netherlands

Model1

Figure 3: Heat map of distances between English language model bits

15

text i as G , the Jaccard similarity J between a model bit M and bit B is given by:

i

(

J M; B

)=

jG \ G j

jG [ G j

M

B

M

B

(1)

Theoretically, J (M; B ) ranges from 0 { in the case of complete dissimilarity between

the two texts { to 1 in the case of complete similarity. This approach has a number of

advantages over more typical bag-of-word approaches to text-as-data-analysis. Most importantly, because we compare sets of 5-grams rather than the frequency of certain terms, we

are better able to capture di erences in the ordering of words. Our ability to capture the

context of certain phrases is also increased by the fact that our approach does not require

removal of stop-words or reliance on extensive pre-preprocessing of strings that may obscure

the meaning of legal phrases. In Figure 3, we charted the textual similarity, as measured

by Jaccard similarity coecients, between all the English language model bits in our applied sample.31 As there are very few light squares besides the diagonal, there seem to be

substantial variation across di erent states' model bits.

To further assess the validity of our success measure, we manually checked whether

di erences in verbatim distance between treaty texts actually capture substantive di erences

in treaty drafting. While Alschner and Skougarevskiy (2016a: 12) makes a credible case for

using Jaccard similarity to compare model bits and concluded bits,32 a closer look at two

bits

concluded on the basis of the United Kingdom's 1991 model bit shows how a modest

word-by-word di erence that is signi cant in legal terms, translates to a substantial change

in the Jaccard similarity coecient (see Appendix A.) While the Belarus-United Kingdom

bit

from 1993 record a relatively high general similarity coecient (0.810) when compared

to the 1991 model, comparing the 1994

between Lithuania and the United Kingdom

yields a substantially lower Jaccard similarity (0.537).33 However, both treaties are actually

bit

quite close mirrors of the United Kingdom's model { the recorded di erence in similarity is

mainly due to three changes made to the model in the Lithuania-United Kingdom bit: (1)

a reformulation of the transfer of funds provision, (2) the addition of a consultation clause,

and (3) a clause specifying the temporal application of the treaty.34

In the analysed sample we also use model bits in French (matched with 46 treaties) and Spanish

(matched with 10 treaties).

32 See also Allee and Lugg (2016).

33 What is also interesting about this treaty in particular is that we know Lithuania in 1993 actively

started working to increase their expertise in the international investment law, and that they adopted a

more active approach to investment treaty negotiations than other former Soviet states (Poulsen 2015: 85).

34 The two concluded bits also have di erent dispute settlement provisions, but they correspond to each

of the two optional provisions the United Kingdom has in their model.

31

16

Model

Austria, 2008

Netherlands, 2004

Austria, 2002

Israel, 2003

USA, 2004

Netherlands, 1997

Mexico, 2008

USA, 1998

United Kingdom, 1991

Denmark, 2000

Malaysia, 1998

Croatia, 1998

Netherlands, 1993

India, 2003

South Africa, 1998

Chile, 1994

United Kingdom, 2008

Switzerland, 1995

Uganda, 2003

Turkey, 2000

Korea, Republic of, 2001

Canada, 2003

France, 1999

Turkey, 2009

Italy, 2003

FYR Macedonia, 2009

China, 1994

Korea,, 2001

Thailand, 2002

Guatemala, 2010

Benin, 2002

China, 1997

Denmark, 1991

France, 1996

Russian Federation, 2001

USA, 1994

Finland, 2001

Germany, 1991

Switzerland, 1986

Sweden, 2002

Cambodia, 1998

China, 2003

Mauritius, 2002

Germany, 1998

Colombia, 2011

China, 1989

Indonesia, 1995

Czech Republic, 1993

Sri Lanka, 1995

Germany, 2005

Burkina Faso, 2002

Romania, 2004

Iran, 2001

Kenya, 2003

Colombia, 2009

Mongolia, 1998

Guatemala, 2003

Jamaica, 1995

China, 1984

Peru, 2000

Greece, 2001

United Kingdom, 1972

0.0

0.3

0.6

Mean similarity between models and BITs

Figure 4: Mean similarity between models and treaties.

17

0.9

After matching model bits and concluded bits, we have 746 unique observations. However, the observations are only based on 700 unique treaties, because when both parties

to the negotiations use model

bits

(of which there are 46 instances), the concluded

bit

enters the data twice (with di erent values on the dependent variable). Figure 4 displays

the average Jaccard similarities and standard deviations for all model bits with at least one

matched

bit

in our sample. The more successful negotiating countries are Austria (with

their 2002 and 2008 models), the Netherlands (2004 model) and the United States (2004

model). Moreover, the relative success of the United Kingdom's 1991 model treaty is perhaps particularly interesting given the high number of bits that have been negotiated based

on this model (24 in our sample). On the other hand of the spectrum, we nd countries

such as Peru (2000 model), China (1984 model) and Jamaica (1995 model).

4.2

Institutional capacity

We use two indicators to capture the institutional capacity that fosters negotiating expertise

at the state level. To capture the relatively broad notion of impartial and merits-based

bureaucracies we apply the Bureaucratic Quality (bq) index from the International Country

Risk Guide (icrg). The

bq

index captures the degree to which \the bureaucracy has

the strength and expertise to govern without drastic changes in policy or interruptions in

government services" at the same time as having "an established mechanism for recruitment

and training" (The PRS Group 2012: 7).35 Increased scores on the bq index corresponds

with higher bureaucratic quality.

To capture the speci c notion of corruption in the civil service, we apply the Public

Sector Corruption (psc) index from the Varieties of Democracy (v-dem) dataset (McMann

et al. 2016). The

psc

index captures the extent to which \public sector employees grant

favours in exchange for bribes, kickbacks, or other material inducements, and how often [...]

they steal, embezzle, or misappropriate public funds or other state resources for personal

or family use" (Coppedge et al. 2016: 67). As such, it is a good measure of patronage and

nepotism. Higher scores on the psc index indicate higher levels of corruption.

It should be noted that since our indicators are indirect measures of negotiating expertise,

some might question the potential problem of random measurement error. Aside from

the fact that there are close theoretical and empirical links between bureaucratic capacity

and corruption control on the one side, and expertise in the bureaucracy on the other (as

35

See: http://www.prsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/icrgmethodology.pdf.

18

discussed in section 3.2), the most likely e ect of using these indirect measures in our analysis

is an attenuation of the results.36 Thus, if anything, the indirect measures should represent

a tough test of our theoretical relationship.

4.3

Control variables

We also control for a number of other aspects that may confound negotiating success. First,

as highlighted in the rationalist choice accounts of

bit-making

(Elkins, Guzman and Sim-

mons 2006, Allee and Peinhardt 2014, Simmons 2014), the size of home markets, as a proxy

for the potential future fdi a negotiator brings to the table, may have an e ect on the concessions parties are willing to make in the negotiations. We therefore include gross domestic

product (gdp) and gross capital formation (gcp) as conrol variables in all of our models.

captures the amount of capital invested per year in a country, and is therefore a more

direct measure of investment activity than gdp.37

gcf

Second, to account for any issue-speci c learning e ect we include two controls. Since the

parties' experience from previous negotiations should a ect their negotiating capacity, we

generate a cumulative count of previous

at the time of concluding a

bit

bits

the parties to the negotiations have concluded

in our sample. However, learning may also emanate from

exposure to disputes. As demonstrated by Poulsen and Aisbett (2013), countries tend to

change their approach to

bits

after they experience an investor claim. To control for this

phenomenon we generate a cumulative count of

ita

claims each party to the case has

experienced at the time of concluding the bit in question. The data on ita claims is taken

from the PluriCourts Investment Treaty and Arbitration Database (pitad) (Behn, Berge

and Langford 2017).

Third, a concern with using model

bits

as preference measures is that, even though

many states have publicly updated their models over time, they are \live" documents. That

means that they are probably also incrementally amended without public disclosure. We

therefore assume that older model bits are less valid measures of countries' preferences than

new ones. To account for this diminishing precision we include a variable that counts the

age of each model (number of years the model has been in force) at the time of conclusion of

a matched bit. For countries with multiple models, we always let the former model expire

This is also referred to as regression dilution, and is driven by random noise in the errors of independent

variables, leading to underestimation of the regression slope's absolute value and biasing it towards zero.

37 Both variables are taken from the World Bank's World Development Indicators. See: https://data.

worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators.

36

19

when a new model is published.

Fourth, we control for the e ect of having a large home-base of multinational investors,

because outgoing investors may try and pressure their governments to conclude

bits

that

are structured in a certain way (Allee and Peinhardt 2014: 64). A larger investor lobby

may also in uence the vigour with which preferences are upheld in

bit

negotiations. We

therefore include a variable that captures the percentage of the worlds' largest multinational

corporations head-quartered in the two parties to the bits in our sample.38

Fifth, we control for aspects pertaining to the negotiating parties historic ties such as

shared cultural origins and legal systems. We therefore introduce three country-pair dummies: Common legal background to account for the fact that some countries have baseline

preferences are more conform than others.39 Shared colonial history, because in these relations the former colonial principal may have knowledge or pressure points vis-a-vis the

colony that makes it more capable of dictating the treaty-terms.40 And, alliance ties, because in these relations the parties should be more worried about jeopardising their alliance,

and as such be more yielding in the negotiations (Allee and Peinhardt 2010: 11).41

Finally, the use of model

bits

may in and of itself be a source of negotiating power.

If only one party to the negotiations brings an explicit model, that model is likely to be

the template from which the negotiations depart.42 As such, the model country is likely

to have a type of framing-power going into the negotiations. If both parties use model

bits

however, the negotiation dynamic should change and it should be more dicult to

succeed for both parties. We therefore create a dummy variable that captures model-model

negotiations (whether both parties to the negotiation brings a model

bit

to the table).

Descriptive statistics for all variables are reported in Table A2, and the correlations are

reported in Figure A1 in the Appendix.

These data were obtained directly from Clint Peinhardt, and are taken from the Forbes magazine's

annual list of the world's largest multinational corporations. To standardise the list across years, all corporations with revenues above $5 billions 1980 us dollars (Allee and Peinhardt 2014: 64-65).

39 This variable is taken from La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes and Shleifer (2008). The legal systems are

French, English, German, Scandinavian or Socialist legal traditions.

40 These data are taken from the Issue Correlates of War (icow) Project Colonial History data set, version

1.0. See: http://www.paulhensel.org/icowcol.html.

41 These data are taken from the Alliance Treaty Obligations and Provisions dataset (Leeds et al. 2002).

Only alliances after the Second World War are taken into account, as almost all states were engaged in some

sort of alliance during the war.

42 As Poulsen (2015) demonstrates throughout his research on bit-making in the developing world.

38

20

4.4

Estimation

We consider a number of strategies to account for hierarchical nature of our dependent variable, where concluded bits are nested in model bits. Our main approach is to acknowledge

that there probably are di erences in the rigorousness with which states apply their models,

and how far from their baseline preferences they are willing to venture. We therefore apply

two di erent estimators. Given the nature of the Jaccard similarity coecient, we use ordinary least square (ols) estimators in both sets of models. In the rst set, we use a random

e ects. In these estimations each model bit is given its own intercept, but the intercepts are

assumed to fall within a common Gaussian distribution. As such, the estimates are based on

the full variance of our data but controls for unobserved heterogeneity at the model treaty

level. The random e ects models represent a moderately strong test of our theory. Second,

we use ols models, with model bit xed e ects, treaty language xed e ects, and standard

errors clustered on model

bits.

Here we also control for unobserved factors at the model

treaty level, and within treaty languages, that may bias the results. With this strategy our

estimates are based solemnly on variation in-between

bits

negotiated on the same model.

As such, the xed e ects estimations constitute very strong tests of our theory.43

For all independent variables where it is feasible, we estimate relational observation

values, meaning we subtract variable values for non-model states in any pairing from the

model state's value.44 This is because we believe that it is the negotiation-speci c asymmetry

between the parties' expertise and material assets the matters, rather than each party's

negotiating assets having independent e ects on the negotiation outcome. In other words,

any given state's ability to persuade it's counterpart, depends on the negotiating expertise

of that counterpart. Thus, in negotiation dyads where the model country has a higher value

on a relational independent variable, the observed value will be positive. In the opposite

case, where the partner state scores better than the model state, it will be negative.

5

Results

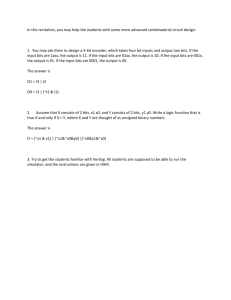

In Figure 5, the bivariate relationships between our two expertise variables and negotiation

success is depicted. Both scatter plots indicate that increasing di erences between negotiating parties' institutional structures conducive to expertise seem to co-vary with increased

43

44

See the number of bits concluded per model bits in Table A1 in the Appendix.

In the regressions tables below we use to denote variables that are estimated in relational terms.

21

● ●

●

0.50

0.25

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●●

●

●

● ●● ●● ●

●

●

●

● ●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●● ●

●●●

●

● ●● ● ●●

●●● ● ●●

●

● ●

●

●●●

● ●

● ●●

●

● ●●

●

●

●

● ● ●●

●

●

●

●●

●● ●●

●●

● ●

●● ● ●● ●

●

●

● ● ●

●●●●●

●●

●●●

●

● ●●

●● ● ●

● ●

● ●

●● ●●

●●

●●

●

●●

●

●

●

●●

● ●● ● ●

●

● ●

● ●

●

●

● ● ● ● ●●

●

●●

●●

●

●

●●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●●

●

●

●●

●●●

●

●● ●

●

● ●● ●

●● ●

●

● ●

●●

● ●

● ●●●●

●

● ●●●●

●

●●

●

●● ● ●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

● ● ●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●● ●

●●●

●

● ●●

●

●● ●●

●

●

●●● ● ● ●

●

●

●

●

● ●●

● ●●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

● ●

●● ●

●

●● ● ●

● ●●●

●●

● ●● ● ● ●

●●● ●

●●

● ●

● ● ●●● ● ●●●●

●●

●

●

●

●

● ●●

● ● ●●

●

●

●

● ●

● ● ●●

● ●●●

●

●

●

● ●

●

● ● ● ●● ● ●

●● ●

●

●

●● ●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ● ● ● ● ● ●●

●

●

● ●●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

●●

●

●●●

●

●●

●

●●

● ● ●●

●

● ●●

● ●● ●

●

● ●● ●●● ● ●

●

● ● ●● ● ●

● ●

● ●●

● ●

●●

●

●●

●●

●●

●●●●

●

● ● ●

●

●●●

●●● ●

●

●

● ●●

●

●

●●●

● ●●

●●

●

●

●

●● ●●●●● ●

● ●● ●

●

●

●

●

●●

●●

● ● ●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

● ●

● ●

● ● ●

●

●

● ● ●● ●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●●

●

●

● ● ●

●

●●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

0.75

Similarity Between Model and BIT

●

●

●

●

●● ●

●

●

●

●

●

0.75

●

●

●

●

●

●

Similarity Between Model and BIT

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

0.50

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

0.25

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●● ●

●

●

●

●

●●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●●

●

●

●● ●

●

●

●●●

●

● ●●●

●

●

●

●●

●

●●●

●●●● ●●●

−1.0

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

0.00

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

−0.5

●

● ●

0.0

0.00

●

●

−2

0.5

●

●

0

●

●

● ●

●

●

2

4

Difference in bureaucratic_quality

Difference in public sector corruption

Figure 5: Negotiating expertise and success in bit negotiations.

success in

bit

negotiations. The results from our multivariate analyses presented in Ta-

ble 1 and 2 reveal that the bivariate relationships largely hold true when controlling for

other dyad-speci c factors, state learning and historic ties between the negotiating parties.

As such, our theory of power-as-expertise seem very robust across both estimation strategies. When model states have higher quality bureaucracies, or lower levels of public sector

corruption than their negotiating partner, they tend to exhibit higher levels of preference

attainment in

bit

bit

negotiations { meaning they manage to reproduce more of their model

verbatim in concluded bits.

While we expected that the size of e ects and the levels of signi cance for the two expertise variables would decreasing as we move from the random e ects to the xed e ects

models, the fact that we nd relationships signi cant at the 95% level in the xed e ects

models is a very strong indication that expertise is associated with success in

22

bit

negoti-

Table 1: Random intercept models: Similarity between model and negotiated BIT

ICRG Bureaucratic quality, standardized

Public sector corruption, standardized

GDP (in millions), standardized

Gross capital formation, standardized

ITA exposure, model state

ITA exposure, partner state

BITs signed

Years since model

Share of MNCs

Same legal origin

Shared colonial history

Alliance tie

Partner state has model

AIC

BIC

Log Likelihood

Num. obs.

Num. groups: modelBITid

Var: modelBITid (Intercept)

Var: Residual

0 001, 0 01, 0 05.

Random intercept for model BITs.

p <

:

p <

:

p <

Model 1 Model2 Model 3

0 16

(0 05)

0 15

(0 04)

0 09

0 12

0 09

(0 07) (0 08)

(0 07)

0 05

0 01

0 05

(0 03) (0 04) (0 03)

0 30

0 42

0 32

(0 16) (0 17) (0 16)

0 26

0 22

0 27

(0 10) (0 11)

(0 10)

0 00

0 00

0 00

(0 00) (0 00) (0 00)

0 03

0 03

0 03

(0 01) (0 01)

(0 01)

1 27

0 37

0 61

(1 21)

(1

45)

(1

25)

0 24 0 19 0 26

(0 07) (0 08)

(0 07)

0 08

0 10

0 08

(0 11)

(0 13)

(0 12)

0 16

0 15

0 15

(0 07) (0 10) (0 08)

0 21

0 25

0 20

(0 09) (0 10)

(0 09)

1445.78 1183.47 1400.35

1508.41 1247.02 1466.79

-708.89 -576.74 -685.17

648

511

620

68

63

68

0.40

0.35

0.37

0.40

0.42

0.41

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

ations. Especially when viewed in light of the expected attenuation of our results induced

by the indirect measures of negotiating expertise. When interpreting the ndings from the

xed e ects models substantively, one standard deviation increase in the di erence between

model states' and partner states' bureaucratic quality is associated with a 0.11 standard

deviation increase in similarity between model bits concluded bits. Inversely, one standard

deviation increase in the di erence between model states' and partner states' public sector

corruption is found to increase the distance between model

bits

concluded

bits

by 0.13

standard deviations.

There are also a couple of other ndings that warrant comments. First, model 1 in both

Table 1 and 2 are baseline models estimated with control variables only. Given the amount

of studies that nd the size of states' home investment markets to impact success in

bit

negotiations, we would have expected that high, positive di erences between model states'

and negotiating partners' levels of production (gdp) and investment (gcf) would to lead

to increased negotiating success. But neither economic variable is statistically signi cant in

23

Table 2: Fixed e ects models: Similarity between model and negotiated BIT

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

ICRG Bureaucratic quality, standardized

0 11

(0 06)

Public sector corruption, standardized

0 13

(0 05)

GDP (in millions), standardized

0 12

0 11

0 12

(0 09) (0 10) (0 09)

Gross capital formation, standardized

0 05

0 03

0 05

(0 04) (0 05) (0 04)

ITA exposure, model state

0 27

0 41

0 30

(0 21) (0 21) (0 23)

ITA exposure, partner state

0 29

0 26

0 31

(0 11) (0 12) (0 11)

BITs signed

0 00

0 00

0 00

(0 00) (0 00) (0 00)

Years since model

0 02

0 02

0 02

(0 01) (0 02) (0 01)

Share of MNCs

1 84

0 99

1 43

(1 14)

(1

47)

(1

20)

Same legal origin

0 27 0 22 0 28

(0 07) (0 08) (0 07)

Shared colonial history

0 06

0 12

0 06

(0 09)

(0

12)

(0

09)

Alliance tie

0 17

0 17

0 17

(0 06) (0 08) (0 06)

Partner state has model

0 23

0 27

0 22

(0 12) (0 13) (0 12)

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

:

0 001, 0 01, 0 05.

Standard errors are clustered on model BITs.

Fixed e ects for model treaties and treaty language are estimated but not reported.

p <

:

p <

:

p <

:

any of the baseline models. This non- nding remains robust through all models controlling

for institutional capacity. One interpretation of these ndings is that the insistent focus on

the material context and rational choice logic when modelling bit negotiations is incoherent

with the actual negotiation dynamics at play, and that the social context seems to matter

more than previously assumed.

It should be noted however that previous studies may have found states' material assets

to matter due model speci cation issues. First, deriving static state preferences from the

North-South dichotomy may have impacted the results.45 More importantly however, the

use of non-relational variable speci cation may have impacted ndings in previous studies.

That is, by entering the negotiating states' economic performance values independently in

regressions instead of estimating the relative di erence between the parties, one assumes

that each party's material assets have an independent e ect on negotiating outcomes. In

Table A6 in the Appendix we re-estimate our three main models with this kind of nonrelational variable speci cation. And indeed, when assessed non-relationally, home markets

seem to matter more for negotiation outcomes.

Second, turning to the variables that capture state learning we nd strong support for

45

But, see Allee and Lugg (2016).

24

the assumption that non-model negotiating parties become better negotiators after they

experience investment arbitration claims under previously negotiated bits. However, we do

not nd states using model

bits

in our sample to exhibit the same learning e ect. There

might be a di erent reasons for this. Even though we have identi ed states that use model

bits

all along the scale of economic development, the majority of concluded

bits

in our

sample are based on models from states with relatively high levels of institutional capacity.46 As such, one can assume that the potential for learning should be larger for most

partner states. Moreover, the mere task of formulating a model bit in and of itself may also

induce issue-speci c learning before the negotiation.47 Poulsen and Aisbett (2013) highlight

another interesting point { the potential economic downside to ita cases represents a comparatively larger burden for developing states than developed states. Therefore, they may

also be more likely to `react' when exposed to ita claims. As for exposure to previous bit

negotiations, we nd no signi cant e ect from having participated in more negotiations than

ones counterpart. One way of interpreting this is that the generation and retention of negotiating expertise within state apparatuses is more important to success in bit negotiations

than issue-speci c learning through experience.

Third, we nd strong, positive relationships between two of the variables capturing

historic ties and success in

bit-making.

When the model state has the same legal origin

as the partner state, there is a signi cant and relatively strong, positive e ect on how

close concluded bits resemble model bits. The same goes for alliance ties. Having a shared

colonial history with ones negotiating partner however, does not seem to signi cantly impact

model states ability to attain their treaty preferences. This might be a re ection of how

newly independent colonies for a long time viewed

bits

as a continuation of colonial era

economic dominance (Poulsen 2015: 50-51).

Lastly, there seem to be some changes to the negotiating dynamic when both parties to

the negotiations have model bits. We nd a relatively stable, negative e ect on the model

state's preference attainment when the partner country also brings a model bit to the table.

This is at least an indication that negotiating with explicit preferences reduces the `framing'

e ect of negotiating based on someone else's default draft.

Our general conclusion based on these ndings is that expertise seem to matter more

63 percentage of all concluded bits in the sample where based on models from states with a score of 3

or higher on the bureaucratic quality indicator, and 45 percent are given the highest score (4).