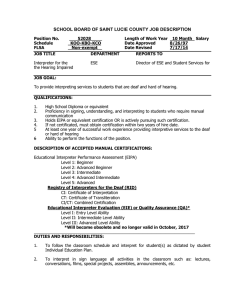

Modality of Instruction in Interpreter Education: An Exploration of Policy Suzanne Ehrlich, Dawn M. Wessling Sign Language Studies, Volume 19, Number 2, Winter 2018, pp. 225-239 (Article) Published by Gallaudet University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/sls.2018.0033 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/717009 Access provided at 3 Oct 2019 01:07 GMT from Texas Tech. University SUZA N N E EHRLIC H A N D D AWN M. W ESSLIN G Modality of Instruction in Interpreter Education: An Exploration of Policy Abstract This study examined the modality of instruction among signed language interpreter education programs in the United States. Faculty members were surveyed to assess their rationale and implementation of language policies within their respective programs. Modality of instruction encompasses spoken languages, signed languages, or a combination of both of these modalities. The researchers identified types of programs based on degree level and language used for instruction. A survey was distributed to identify language use during instructional interactions with interpreting students, with special attention paid to sign language interpreting programs. Results of this study indicated faculty members’ choice of language of instruction was primarily driven by course content. Other themes identified as motivating factors for support (or not) of language policies for instructional purposes included student comprehension and program needs. Translation and inte rpreting students’ practical education ideally begins once students “have a ‘near perfect’ command of their working languages” (Gile 2009, 220). Many academic programs have shifted to a focus that delineates between teaching language and Suzanne Ehrlich is an assistant professor in the University of North Florida’s Educational Technology, Training, and Development program and has presented ­nationally and internationally on the topics of e-learning integration for interpreter education. Dawn M. Wessling is an associate instructor and staff interpreter in the American Sign Language/English interpreting program. 225 S i gn Language Studi e s Vol . 19 N o. 2 Wi nte r 2019 226 | Sign Lang uag e Studi e s teaching interpreting (Sawyer 2004, 3). To further complicate matters, the assumption that all interpreting students have the same level of competency in their L1 may or may not be accurate. A variety of strategies have been developed, from screening students prior to entry into a program to testing students at critical points in their program of study, as well as remediating deficiencies and incorporating a comprehensive examination at the conclusion of a student’s program of study. Oftentimes, pedagogical decisions are rooted in “trial and ­error in the classroom” rather than any grounding in empirical studies (Winston 2013, 179). Students who are learning to interpret in signed languages are acquiring languages that are produced using a different modality than their spoken language(s). In many cases, students have not yet achieved native-like fluency in the signed modality, yet they are acquiring skills based on the process of interpreting (Walker and Shaw 2011). Studies have indicated that for American Sign Language (ASL)-English interpreters the modality of a language is not impactful on the cognition of that language (Corina and Vaid 1994). If the unspoken aim for interpreter educators is to enhance interpreting student’s biliteracy in all of their working languages, then achieving such biliteracy creates challenges on several levels for both the student and for the interpreter educator in determining how to best prepare students for their future professional work. Language policies, the practice of creating policy to favor one language over another or to enforce utilization of a particular language, have emerged as more common practice in interpreting programs (Reagan 2010). If a language policy focuses primarily on signed language, consideration should be given to the concept that educators are teaching in a language in which some students may not have sufficient fluency. This may be considered a practice that more closely resembles status planning, rather than a clear effort to establish a language policy (Reagan 2010). Another concern for interpreting programs is the lack of employed qualified faculty who are deaf and use a signed language as their native language (NL).1 Without a strong deaf faculty presence in programs, interpreter educators are lead to encourage students to engage in interactions in the local deaf community with the intent that this will increase the students’ fluency in their nonnative lan- Instruction Modality in Interpreter Education | 227 guage (L2) (Cenoz and Jessner 2000). This practice parallels well with other language learning methods that encourage students to visit or reside in another country that uses the student’s second target language (TL) in order to increase their fluency in that second language (Gile 2009). The expectation of this study, and its results, is to foster dialogue among individuals researching and working in interpreter education regarding evidence-based decisions around language policies for instruction. History of Interpreter Education Interpreter education has a strong genesis in other fields that include vocational rehabilitation and missionary preparation (Ball 2013). Originally, in the United States the first students enrolled in interpreting programs entered with the expectation that they were already fluent in ASL and English and were considered to be established biliterates. This consideration influenced the design of interpreter education programs during the early stages of the field’s development, resulting in curricula that primarily focused on teaching interpreting skills rather than solidifying language skills. Of additional importance is that these early programs had a strong vocational focus in that they were more often geared toward workforce readiness. The aim of these programs at their inception was to develop interpreters who were ready to enter the workforce immediately upon graduation. From the historic beginning of interpreter education in 1948 rooted in religious interpreting to the current practice today, educators have had to adjust their focus from teaching interpreting to building language competency (Ball 2013). A recent shift of interpreting programs implementing an approach of teaching primarily in a signed modality appears to be resulting in a decreased emphasis on the students’ spoken language skills. To complicate this issue further, interpreter educators may not be heritage users of ASL, nor may they have the pedagogical foundation to effectively teach a second language, despite their qualifications to teach interpreting. McDermid’s (2009) study of interpreting programs in Canada found that their programs often separate the faculty by those who teach language and those who teach interpreting. Regardless, interpreting programs are still cognizant of the language deficits, in both spoken and signed modalities, yet may 228 | Sign L ang uag e Studi e s have teaching philosophies that include no formal stance on language policy, and instead may use various approaches such as total immersion and bilingual/bicultural approaches. There are currently about 170 interpreter education programs throughout the United States, ranging from certificate-level to doctoral­-degree programs. The most comprehensive framework for interpreter education curricular standards was produced by the Conference of Interpreter Trainers operated by the Commission on Collegiate Interpreter Education (CCIE 2014). CCIE’s standards address several areas including faculty qualifications, assessment of student language competency, knowledge of interpreting studies, continuing development of language fluency, and field experience requirements. Missing among these competencies is how to teach language within an interpreting program (Napier 2006). There is a dearth of evidencebased research to support practices regarding language learning in the context of pursuing an interpreter education certificate or degree. Curricula Design and Philosophy McDermid (2009) identifies three categories of curriculum: explicit, implicit, and null, within interpreter education programs. Foundational skills in ASL are typically part of an explicit curriculum that includes specific course sequencing throughout the program of study, while attainment of native-like fluency may be a part of the implicit curriculum. The implicit curriculum is similar to what Sawyer (2004) identifies as the hidden curriculum that “instills values and beliefs that shape future members of the professional community” (42). Examples of the ways in which the implicit curriculum may be applied to language learning is evident in how students are encouraged to be involved in deaf community events; directing students to socialize with deaf people outside of interpreting practice. Of concern is the null curriculum, or that which is not taught in programs of study. One example McDermid (2009) suggests is in regard to programs not teaching transliteration. Other examples of null curriculum might either include DeafBlind interpreting, working with deaf interpreters, or pro-tactile/haptic interpreting strategies as there are few programs that teach this beyond introduction. Determinations regarding the type of content taught within a program of study are typically based Instruction Modality in Interpreter Education | 229 on the skills that are in greatest demand immediately upon entering the workforce and less focus is given to skills that are less common to everyday exercise in general practice. Second Language Teaching and Learning Second language acquisition is well researched and examines both the study of individuals learning a second language and the cognitive processes involved in learning a second language (Saville-Troike 2006). Acquisition of a signed language as a second language follows the same cognitive processes as learning a second spoken language (Woll 2012). The cognitive anatomy for “language processing is not determined by the auditory input modality” and so one might think that modality should not determine language proficiency (Campbell, MacSweeney, and Waters 2008, 5). The modality of languages does not appear to suggest differences in the ability to learn them, but the process for learning a signed language is often different from spoken languages (Williams 2011). Students may be instructed in their NL or in the TL, or in some combination of both. A chapter by Rosen and colleagues (2014) suggests that students learning ASL gain greater vocabulary retention through a “voice-off ” approach or through the TL method of instruction. However, some of these students benefited from a mixed method of NL/TL teaching, depending on individual learning styles, which includes visual or auditory processing styles. The least effective modality for vocabulary learning was “voice-on.” Furthermore, they suggested that educators must “. . . appreciate and ascertain the diversity of language processing schemas employed by their learners prior to selecting the language of instruction in their classrooms” (170). This may indicate that the selection of modality for instruction should be fluid and dependent upon the students’ needs rather than the educator’s preference or program language policy. In interpreting programs where the second language is another spoken language, students will often live and learn within a country where the TL is in the majority. Conversely, there is no “deaf ” country that will facilitate natural learning for signed languages and students often learn in a classroom and through contrived interactions with the deaf community. The Signing Naturally curriculum is used by many 230 | Sign L ang uag e Studi e s programs in the United States and suggests a functional-notional approach to teaching ASL (Smith, Lentz, and Mikos 2008). This concept uses contextually authentic situations in order to guide students in their understanding of how the language functions within particular settings. Smith, Lentz, and Mikos’s (2008) curriculum for postsecondary programs recommends lesson objectives to teach signed languages, with an aim of acquiring the TL as it is used in conversational (i.e., informal) contexts, rather than preparing students to become fluent in all registers of the language. This results in a reduction of exposure to other critical aspects of language development and fluency in their second language, and in some cases an erroneous self-determination of fluency. As Bienvenu (2014) suggests, interpreters and interpreter educators may not have the same working definition of what it means to be bilingual in a signed and spoken language exchange. In many areas of the United States, students may already be bilinguals of spoken languages, namely Spanish and English.This additional spoken language fluency is not formally incorporated in any interpreting programs within the United States, although there are several resources available through the National Consortium of Interpreter Education Centers (2014). In addition to these resources, there are existing qualification exams such as the Texas Board for Evaluation of Interpreters that assess for trilingual interpreting skills (Texas Department of Health and Human Services 2016). Curricula Decisions in Interpreter Education One issue within contemporary work for signed language interpreting is the readiness to work gap of graduates from interpreter education programs. Despite continuous improvement to curricula and increasing numbers of empirically based teaching practices, many students are graduating without certification from associate, baccalaureate, or master’s level programs (Williams 2011).While this is not an indication that students are not qualified and well prepared, it does propose a potential issue in determining their ability to provide adequate services from a consumer perspective (Steinberg, Sullivan, and Loew 1998). Lack of proficiency in ASL is often cited as one reason for the gap from school to work (Quinto-Pozos 2005). Curriculum design and enhanced skill development across an entire program are also con- Instruction Modality in Interpreter Education | 231 cerns in interpreter education programs (Cokely 2005; Humphrey and ­Alcorn 2007). Consideration must also be given to the high failure rate (70 percent) for the current iteration of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) National Interpreter Certification Interview and Performance Exam (RID 2014). The written portion of the RID test has a much lower failure rate (16 percent). This might suggest that interpreter education programs are preparing their students for the work only in theory but not in practice or application. Methods of instruction in interpreter education programs in the United States have recently moved toward a full-immersion approach, which is an effort to teach using only signed language, primarily ASL. The effort to immerse students in one of the TLs (i.e., ASL) overlooks the need for practice to gain fluency in both languages. The idea of using one modality during instruction reinforces a narrow assumption regarding modality and directionality.There is an unspoken belief that much of interpreting directionality will be into ASL. To further complicate matters, delivering new content to students in this second language may decrease the efficacy of their learning. While this may be viewed as an attempt to mimic the language immersion experience that has been effective in second language learning for spoken languages, it begs the question as to whether students are fluent enough to receive and comprehend such information. There are few universities that can offer a true immersion experience in signed language that resembles a visit to another country, as noted earlier. However, such an immersive environment can be experienced at Gallaudet University or the National Technical Institute for the Deaf, where the university and its students use ASL as their primary language in all facets of campus life. Historically, at the inception of interpreting programs in the 1980s, programs were built on the preconceived notion that students entering interpreting programs would have a foundational level of knowledge in ASL. Often those who were already involved with the deaf community as either family or friends of deaf community members, sought to further their education in interpreting. Throughout the decades, programs have shifted to accepting and attracting students who have a general interest in the profession, but may have no prior language exposure or cultural knowledge as it pertains to the deaf 232 | Sign L ang uag e Studi e s community. This shift in program recruitment and acceptance has created a new challenge for associate-level programs, whose brief window of learning (typically two years), creates an unexpected and often challenging paradigm in which students are learning a second language while concurrently studying to become interpreters of that language. Without the necessary fluency to operate in their second language, students were often frustrated by their lack of fluency resulting in attrition, or even the prospect of entering the workforce underqualified and ill-prepared. The baccalaureate experience in interpreter education in the United States was conceived as one way to meet the challenges ­(Annarino and Stauffer 2010). This education shift is further supported by the requirement that a prospective test-taker must possess a bachelor’s degree before they may sit for the RID Certification Performance Exam. The goals of this shift were to increase language exposure and extend time in the program for students by one or two more years, beyond the limited time in the associate-level, thus allowing for greater depth in language learning. The notion was rooted in an anticipation that a more comprehensive experience provided by a bachelor’s program could bridge the existing language learning gap in fluency that has been identified as an issue in interpreting programs (Annarino and Stauffer 2010). Research concerning interpreting students’ experiences, their readiness to work postgraduation, and the challenges of acquiring a second language has been in existence for well over a decade. One response by some interpreter educators during this period of development may be attributed to the creation of a language policy in which educators are to use a monolingual approach, using ASL as the only language of instruction. With the emerging trend of instituting language policies, our study has sought to investigate the motivation behind this pedagogical change, and the decision-making processes of programs that institute specific language policies regarding the language of instruction, which includes any empirical reasoning that might have influenced these decisions. Methods The data were collected using an electronic survey via Qualtrics software (2016), and included demographic information, such as geo- Instruction Modality in Interpreter Education | 233 graphical information regarding the educator’s teaching location, faculty rank, program type, and graduation rates. The survey consisted of seven questions that primarily focused on the decision-making behind language of instruction in teaching interpreting in USbased institutions. The survey was distributed to both associate- and baccalaureate­-level signed language interpreter education programs. The survey yielded forty-three responses, however only thirty-one respondents completed all questions. The survey questions were developed to gather data regarding the rationale and considerations made when determining which language modality was used to teach interpreting courses (i.e., whether a spoken and/or signed language was chosen). The survey data also captured subjective assessments of faculty member’s use of language in the classroom from the student perspective.The survey was emailed to programs listed in the RID database and, employing the snowball sampling method, links to the survey were posted via social media (Atkinson and Flint 2001). This snowball effect yielded a majority of responses from programs in the United States and a few responses from outside of the United States. Discussion The survey data of the respondents (N = 31) revealed an even distribution of modality use in the classroom (signed or spoken) as well as motivation and reasoning for using a particular modality. The survey data examined six items including: (1) length of program, (2) language of instruction policy, (3) rationale for policy, (4) graduation rate, (5) professional role of survey participant, and (6) location of participant. Of the respondents, approximately 72.41 percent were faculty responsible for direct instruction. However, this study’s survey data revealed that these practices in signed language programs suggest that there is great variety in what methods educators are actually employing to enhance language fluency. One area of particular interest is determining which of these are existing practices within a program and which are evidence-based practices (see Winston 2013). Existing practices are those that may not be formal whereas evidence-based practices are formalized and informed by current trends and research. One of the most notable data points from the survey respondents was that there was a somewhat even division between programs with 234 | Sign L ang uag e Studi e s F i g ure 1. Survey question: Does your program have a requisite or mandated language of instruction? and without an explicit language policy. As seen in figure 1, fourteen of the thirty-one survey respondents reported having a language policy of instruction, which is slightly less than half. For those with a formal language policy in place, only signed language was selected as the requisite language of instruction (see figure 1). Whether or not programs had a policy in place, the educators selected several different rationales for this decision.The survey data indicated that policies were or were not implemented for such factors including: • • • • • Language use dependent on content (59.26 percent) Student language needs and comprehension (14.81 percent) Other (11.11 percent) Instructor choice (7.41 percent) Program needs (7.41 percent) Respondents were able to provide additional comments via the ­“other” response selection. These responses related language of instruction to instructors’ levels of competency in the language. Additional responses suggested students may not have the same level of comprehension in ASL as they do when using spoken English. Of interest is the lack of responses that suggested that language policies were implemented in order to provide access for deaf faculty in the work environment. Instruction Modality in Interpreter Education | 235 This may be due to deaf faculty often teaching only language courses (McDermid 2009). The researchers acknowledge the small sample size of the study, however, the limitations in research surrounding interpreter education pedagogy may be due in part to the small number of interpreter educators in the United States. A recent membership report indicates that the Conference of Interpreter Trainers has 309 members (Doug Bowen-Bailey, CIT webmaster, personal communication, July 21, 2017). The hope is that this study will encourage more in-depth research of interpreter educators and programmatic language policies (both implicit and explicit) in order to better prepare interpreting students for their future practice. Upon the analysis of the data related to program graduation rates, close to half of the respondents (48.28 percent) were unable to identify the graduation rates for their students and selected unknown. Of those who were able to report an estimated graduation rate (33.40 percent of the respondents), the average graduation rate was reported to be 82.90 percent. Respondents’ who provided location indicated primarily in the Americas (89.66 percent), with some representation from Europe (6.90 percent) and Australia (3.45 percent).The international responses were unexpected but yielded responses similar to those within the Americas suggesting that there may be similarity between trends in the Americas related to sign language interpreter preparation and those that may be in existence in other parts of the globe. Conclusion The distinction between language immersion for experience and language policy for pedagogical reasons bears further examination. Clearly, the need to further students’ exposure and development in both languages is of paramount importance in any interpreter education program. As interpreter education pedagogy seeks to enhance practice that is evidence-based, we must also consider what other evidence is needed to inform our decisions on language modality in the interpreter education classroom. The impact of language of instruction on students’ retention and comprehension of course content in the interpreter education classroom might be investigated through qualitative and quantitative design to include ethnographic studies of 236 | Sign L ang uag e Studi e s programs, focus groups with interpreter educators, interviews with student interpreters, and discussions with deaf consumers of interpreting services, and longitudinal assessment of student outcomes. Areas of additional investigation that would be valuable include examination of the ways in which we orchestrate language experiences in the classroom to mimic authentic interaction. Coupling this process with the limitation of the use of only one language to teach a process that involves two language modalities seems counterintuitive. One might also investigate this phenomenon as it relates to the creation of an artificial language learning environment.This study also brought to light the need for further research as to whether students’ comprehension is statistically and substantially greater as a result of a monolingual environment. Lastly, this research topic would benefit from further comparative studies that highlight educational values between artificial immersions within the classroom versus real community interactions as learning tools. There is not a one-size-fits-all solution to any interpreter education program, as the individuality of each program and its curricular design provides a unique point of view that is rooted in local deaf community needs and enhances the experiences of students. A pedagogical philosophy embedded in differentiated instruction ­(Santangelo and Tomlinson 2009), seeks to maximize learning for all students through diverse avenues of teaching and assessment (Iris Center 2018). Linguistic diversity and flexibility are critical to supporting acceptance of language in the many forms it is represented. By embracing this variety, interpreter educators will be encouraging respect for all languages used by interpreters. This will provide for the most effective solution for communication and ultimately all communities will be positively impacted, most especially the deaf community. The suggestion that language policy should be dichotomous is not beneficial to any of the stakeholders. Let the choice of the interpreter educator not be one or the other, but rather that all languages are valued and welcomed. Note 1. The decision to use the lowercase form of deaf is done to acknowledge that the people who use signed languages have discretion in how they wish Instruction Modality in Interpreter Education | 237 to be identified (Woodward and Horejes 2016). Since we are not members of this cultural group, it is not appropriate for us to decide their cultural identity by capitalizing the term. Further, there are sub-groups within the deaf community to include DeafBlind, LGBTQ, and ethnicity. The author is using a generic lowercase term to encompass everyone. References Annarino, P., and S. Stauffer. 2010.AA-BA Partnerships: Creating New Value for Interpreter Education Programs 2010. National Consortium of Interpreter Education Centers (Monograph). Retrieved from: http://www.interpretereducation .org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Monograph.pdf. Atkinson, R., and J. Flint. 2001. Accessing Hidden and Hard-to-Reach Populations: Snowball Research Strategies. Social Research Update 33 (1): 1–4. Ball, C. 2013. Legacies and Legends. History of Interpreter Education from 1800 to the 21st Century. Alberta, Canada: Interpreter Consolidated. Bienvenu, MJ. 2014. Bilingualism: Are Sign Language Interpreters Bilinguals? Street Leverage. [Online Article]. Retrieved from https://www.streetleverage .com/2015/05/bilingualism-are-sign-language-interpreters-bilinguals/. Campbell, R., M. MacSweeney, and D. Waters. 2008. Sign Language and the Brain. A Review. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 13 (1): 3–20. CCIE. 2014. Accreditation Standards 2014. Retrieved from http://ccie -accreditation.org. Cenoz, J., and U. Jessner, eds. 2000. English in Europe:The Acquisition of a Third Language. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters. Cokely, D. 2005. Curriculum Revision in the Twenty-First Century. In ­Advances in Teaching Sign Language Interpreters, ed. C. B. Roy, 1–21. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. Corina, D. P., and J. Vaid. 1994. Lateralization for Shadowing Words versus Signs: A Study of ASL-English Interpreters. In Bridging the Gap. E ­ mpirical Research in Simultaneous Interpretation, ed. S. Lambert and B. Moser-­Mercer, 237–48. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Gile, D. 2009. Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Hoza, J. 2010. Principles and Practice: Teaching Team Interpreting as Collaboration and Interdependence. Connecting Our World 3. Humphrey, J. H., and B. J. Alcorn. 2007. So You Want to Be an Interpreter? An Introduction to Sign Language Interpreting. Benton, WA: H&H. Iris Center. 2018. Differentiated Instruction: Maximizing the Learning of All Students. Retrieved from https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/di/. McDermid, C. 2009. The Ontological Beliefs and Curriculum Design of Canadian Interpreter and ASL Educators. International Journal of Interpreter Education 1:7–32. 238 | Sign L ang uag e Studi e s Napier, J. 2006. Effectively Teaching Discourse to Sign Language Interpreting Students. Language, Culture and Curriculum 19 (3): 251–65. National Consortium of Interpreter Education Centers. 2014. Tri­lingual Interpreting. Retrieved from http://www.interpretereducation.org/specialization /aslspanishenglish/. Qualtrics [computer software]. November 2016. Provo, UT: Qualtrics. Quinto-Pozos, D. 2005. Factors that Influence the Acquisition of ASL for Interpreting Students. In Sign Language Interpreting and Interpreter Education: Directions for Research and Practice, ed. M. Marschark, R. Peterson, and E. A. Winston, 159–87. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Reagan,T. 2010. Language Policy for Sign Languages.Washington, DC: ­Gallaudet University Press. Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. 2014. NIC Validity, Reliability, and Candidate Report. Alexandria, VA: Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Rosen, R., M. DeLouise, A. Boyle, and K. Daley. 2014. Native Language, Target Language, and the Teaching and Learning of American Sign Language. In Teaching and Learning Sign Languages. International Perspectives and Practices, ed. R. Rosen, D. McKee, and R. McKee, 145–74. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan. Santangelo, T., and C. A. Tomlinson. 2009. The Application of Differentiated Instruction in Postsecondary Environments: Benefits, Challenges, and Future Directions. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 20 (3): 307–23. Saville-Troike, M. 2006. Introducing Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: ­Cambridge University Press. Sawyer, D. S. 2004. Fundamental Aspects of Interpreter Education: Curriculum and Assessment. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Smith, C., E. Lentz, and K. Mikos. 2008. Signing Naturally.Teacher’s Curriculum Guide. Units 1–6. San Diego: DawnSignPress. Steinberg, A. G.,V. J. Sullivan, and R. C. Loew. 1998. Cultural and Linguistic Barriers to Mental Health Service Access:The Deaf Consumer’s Perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry 155 (7): 982–84. Texas Department of Health and Human Services. 2016. Board for Evaluation of Interpreters[website]. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs /leadership/advisory-committees/board-evaluation-interpreters-bei. Walker, J., and S. Shaw. 2011. Interpreter Readiness for Specialized Settings. ­Journal of Interpretation 21 (1), article 8. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons .unf.edu/joi/vol21/iss1/8/. Williams, C. L. 2011. Sojourners of the Master Mentor Program: A Study of Effective Practice PhD. diss., Capella University. ProQuest (AAT 3464682). Instruction Modality in Interpreter Education | 239 Winston, E. 2013. Infusing Evidence into Interpreting Education. In Evolving Paradigms in Interpreter Education, ed. E. Winston and C. Monikowski, 164–87. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. Woll, B. 2012. Second Language Acquisition of Sign Language. In Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, ed. C. A. Chapelle. Chichester, UK:Wiley-Blackwell. Woodward, J., and T. P. Horejes. 2016. deaf/Deaf: Origins and Usage. In The Deaf Studies Encyclopedia, ed. G. Gertz and P. Boudreault, 284–87. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.