Virtue Ethics: Aristotle, Aquinas, Kant - Philosophy Assignment

advertisement

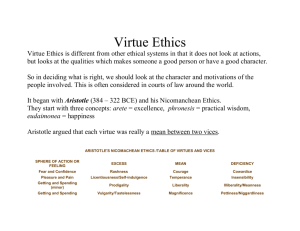

Estenzo, Nieva Marie Cantano, Chenny Marie Mendoza, Jubhin Haze Conde, Angela PHILO101 MWF 7:30 AM – 8:30 AM Miss Chrisley Ann Arsua 10/09/2019 ASSIGNMENT IN ETHICS Research what are the ideas and thoughts of the following philosophers about virtue ethics a. Aristotle b. St. Thomas Aquinas c. Immanuel Kant Researches from online sites: a. Aristotle Aristotle's perspective on ethics was based on the virtue of being human; in other words, virtue ethics. There are two important distinctions between Aristotle's approach to ethics and the other predominant perspectives at the time. First, Aristotle did not consider ethics just a theoretical or philosophical topic to study. To understand ethics, Aristotle argued, you actually have to observe how people behave. That led to the second distinction. Ethics weren't about ''what if'' situations for Aristotle; instead, he took a very practical approach and much of his ideas on ethics were based on what someone did and how their virtues impacted their actions. Nicomachean Ethics & Virtue Nicomachean Ethics is the name of a series of books that Aristotle wrote about ethics. In these writings, he uses logic to determine a definition and the potential impacts of ethics. He starts his presentation of ethics with a simple assumption: humans think and behave in a way to achieve happiness, which Aristotle defined as the constant consideration of truth and behavior consistent with that truth. Aristotle defines virtue as the average, or 'mean,' between excess and deficiency. Basically, he says, the idea of virtue is ''all things in moderation.'' Humans should enjoy existence, but not be selfish. They should avoid pain and displeasure, but not expect a life completely void of them. By striving to live this virtuous life of moderation, human beings can find happiness and, therefore, be ethical. Most importantly, going back to one of the differences between virtue ethics and other theories of ethics, morality or being ethical cannot be achieved abstractly, meaning it cannot only be based on someone's beliefs. Ethical behavior requires behavior by individuals in a social environment. For Aristotle, virtue controls happiness and is required for happiness, but is not identical to happiness. Rather, happiness requires both complete virtue and a complete life where life here is understood be the provisional goods of life. b. St. Thomas Aquinas St. Thomas Aquinas studied Aristotle's ideas about virtue ethics and re-interpreted them from a Christian point of view. He agreed with Plato and Aristotle about the four cardinal virtues: prudence, temperance, justice and fortitude. He stated that they are natural and revealed in nature, and that they are binding on everyone. He went on to suggest, though, that there are also three theological virtues namely faith, hope, and charity. According to Aquinas, the object of the theological virtues is God Himself, who is the last end of all as surpassing the knowledge of our reason. These virtues differ from cardinal virtues in that they cannot be obtained by human effort. Aquinas believed that a person can only receive them by their being "infused"-through Divine Graceinto the person. Contemporary readers can see this integration in Aquinas’s developed account of human virtue. Instead of focusing purely on a theoretical understanding of the nature of a good moral character, Aquinas also provides practical instruction for living well. When he discusses virtues and vices in the Summa theologiae, for example, he addresses not just abstract questions, such as how we should define virtue, but also practical issues, such as how to show gratitude toward someone who does us a favor we are too poor to repay. This dual concern shows up repeatedly in his ethical works and underscores his commitment to putting belief into action. c. Immanuel Kant Immanuel Kant’s most thorough discussion of virtue is in his Doctrine of Virtue (Tugendlehre), which is the second part of his late work The Metaphysics of Morals. Kant explains virtue as a kind of strength or fortitude of will to fulfill one’s duties despite internal and external obstacles. Kant distinguishes the realm of ethics, which concerns moral ends, attitudes, and virtue, from the realm of justice, which concerns rights and duties that can be coercively enforced. Although we speak of many virtues, Kant says repeatedly, there is just one virtue. Virtue ethics can account for the intuitive aspects of Kant’s deontology. First, it affirms that some laws apply universally and necessarily. This universality is explained by the fact that human beings share a common nature and it is necessary insofar as a human being necessarily has the natural ends it has if it is human. Life is essential to human beings; therefore, it is contrary to their good to murder them and therefore always immoral. Another example: it is never the case that one ought to seek what is false because it is the natural end of our rational faculty that it discovers truth. To claim otherwise requires that you use your rational faculty to say something true about the nature of your rational faculty. It is self-contradictory. So, it is clearly always good to seek the truth, and always bad to distort it. Second, it also affirms that if an alien species were to exist, we would have some identical moral obligations toward each other despite having different biological natures because we share the same metaphysical nature as rational beings. Third, it affirms that someone who does their duty despite the inclinations that pulls in the opposite direction is doing something right because reasons function is to direct activity to the fulfillment of its proper end. But of course, this cannot be the whole story as we shall see. Lastly, it affirms that a will that does not value virtue or a person for their own sake cannot possibly be doing something virtuous or good. Just as our well-being is an end, so too is the well-being of another individual that shares the same rational nature. We are social creatures that have it as our end to be a part of something more than ourselves. it dehumanizes us and is unnatural in so-far as it requires that we act only from duty and never from inclination. But to be inclined to something just for the will to be moved (at least in part) toward a certain action.