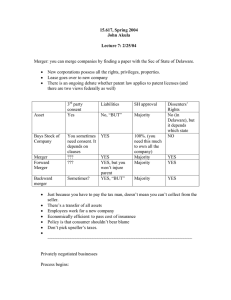

Letters of Intent in Mergers and Acquisitions: Practical Tips for Negotiating (and Preparing) All rights reserved. These materials may not be reproduced without written permission from NBI, Inc. To order additional copies or for general information please contact our Customer Service Department at (800) 930-6182 or online at www.NBI-sems.com. For information on how to become a faculty member for one of our seminars, contact the Planning Department at the address below, by calling (800) 777-8707, or emailing us at speakerinfo@nbi-sems.com. This publication is designed to provide general information prepared by professionals in regard to subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. Although prepared by professionals, this publication should not be utilized as a substitute for professional service in specific situations. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a professional should be sought. Copyright 2018 NBI, Inc. PO Box 3067 Eau Claire, WI 54702 80005 IN-HOUSE TRAINING Can training your staff be easy and individualized? It can be with NBI. Your company is unique, and so are your training needs. Let NBI tailor the content of a training program to address the topics and challenges that are relevant to you. With customized in-house training we will work with you to create a program that helps you meet your particular training objectives. For maximum convenience we will bring the training session right where you need it…to your office. Whether you need to train 5 or 500 employees, we’ll help you get everyone up to speed on the topics that impact your organization most! Spend your valuable time and money on the information and skills you really need! Call us today and we will begin putting our training solutions to work for you. 800.930.6182 Jim Lau Laurie Johnston Legal Product Specialists jim.lau@nbi-sems.com laurie.johnston@nbi-sems.com Letters of Intent in Mergers and Acquisitions: Practical Tips for Negotiating (and Preparing) Author James S. Bruce K&L Gates LLP Charleston, SC Presenter JAMES S. BRUCE is a partner with K&L Gates LLP, where he represents clients in mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures, and other business transactions. He advises Fortune 500 companies, as well as middle-market and emerging growth companies in a broad range of industries. Mr. Bruce also represents private equity firms, corporate strategic investors and distressed company investors. He is admitted to practice in Georgia and South Carolina. Mr. Bruce earned his B.A. degree from Washington and Lee University, and his J.D. degree from Georgetown University Law Center. NBI Teleconference Letters of Intent in Mergers and Acquisitions: Practical Tips for Negotiating and Preparing James S. Bruce Partner K&L Gates LLP © Copyright 2018 by K&L Gates LLP. All rights reserved. OVERVIEW Letter of intent (“LOI”) Structured as a formal letter, usually from buyer Sets forth certain preliminary terms of deal Establishes a deal roadmap Useful, but not appropriate for every transaction Other similar documents Term sheet Memorandum of understanding Commitment letter klgates.com 1 2 PURPOSES OF A LETTER OF INTENT Summarizes the key terms of a potential deal Most of the material terms are not binding Allows parties to determine how close (or far apart) the two sides are Establishes a roadmap for the transaction Sets the tone for the ensuing negotiations Lays out key dates and deadlines klgates.com 3 ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES Factors to consider Complexity and timing of the deal Desire for exclusivity Disclosure obligations Regulatory approvals needed Leverage of parties Sophistication of parties and counsel For some deals, cost of negotiating the LOI may outweigh its benefits klgates.com 2 4 BUYER CONSIDERATIONS Eliminate competition Exclusivity No-shop provision Break-up fee Access to the business Buyer wants as much as possible Business as usual Operating covenants from seller klgates.com 5 SELLER CONSIDERATIONS Capitalize on leverage Seller wants material terms in the LOI Preserve the business Delay Buyer’s ability to access key employees Restrict access to customers and suppliers Prevent business disruption Protect proprietary information Separate Non-Disclosure Agreement klgates.com 3 6 BINDING VS. NON-BINDING Most terms are not binding Intention is to leave room for negotiation Superseded by definitive purchase agreement Expressly designate which provisions are binding and which are not Otherwise court may find LOI inadvertently binding klgates.com 7 BINDING VS. NON-BINDING Typical binding terms include: Exclusivity Break-up / Termination fees Confidentiality Expenses Termination No third-party beneficiaries Governing law Scope of binding terms klgates.com 4 8 DUTY TO NEGOTIATE IN GOOD FAITH May apply even if LOI not binding Requires parties to attempt to reach agreement LOI may include express duty to negotiate in good faith State laws vary as to whether courts will enforce Some states may impose duty even in absence of express provision klgates.com 9 DUTY TO NEGOTIATE IN GOOD FAITH: STATE-BY-STATE SURVEY klgates.com 5 10 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Parties Identify actual buyer and seller entities Acquisition subsidiary / purchaser designee May include parent guarantors / stockholders Deal type and structure Asset acquisition / stock acquisition / merger Deal structure will affect drafting and timeline Outline assets and assumed liabilities for asset deal Describe structure of merger klgates.com 11 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Purchase Price Cash, stock, promissory note or combination Generally assumes no encumbrances Assumption or payoff of debt Escrow Amount Purpose Fixed dollar amount vs % of purchase price Duration klgates.com 6 12 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Purchase price adjustments Net Working Capital Adjustment Net Worth Adjustment Earnout Important to flag in LOI if buyer is proposing Can bridge value gap Outline metrics for achieving earnout payments Seller likely to resist deferred purchase price Often lead to post-closing disputes klgates.com 13 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Due diligence access Level of access / timing Buyer Wants immediate and full access / due diligence review is critical to appropriately evaluating business Will want this to be binding Consider timing and other constraints in scope of request Seller Concerned with minimizing disruptions to business May want to limit access or stage disclosure klgates.com 7 14 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Closing Target date vs mutual agreement Purchase Agreement Outline expectations for definitive agreement Set target for timing / drafting responsibility Generally reference provisions to be included: Representations and warranties Closing conditions Restrictive covenants Indemnification klgates.com 15 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Closing Conditions Often simply refer to “customary” conditions Specific conditions can include: HSR clearance Material consents Financing out Due diligence out Board / shareholder approval Seller – Should seek to minimize conditions to closing klgates.com 8 16 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Conduct of Seller Business Ordinary course Affirmative covenants Preserve business Retain key employees Maintain relationships with customers and suppliers Negative covenants No unusual compensation increases No dividends inconsistent with past practice Capital expenditure commitments No material contracts outside ordinary course w/o consent klgates.com 17 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Exclusivity LOIs often include a “no-shop” provision Critical provision from buyer perspective Keeps seller from negotiating with other parties or soliciting other offers for a fixed period of time Consideration is cost and time of diligence required Another binding provision klgates.com 9 18 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Expiration / Termination of LOI Expiration date usually included Buyer’s ability to terminate LOI Surviving provisions Break-up Fee Seller pays to break exclusivity for superior deal Reverse Break-up Fee Buyer pays if deal falters for failure to secure financing klgates.com 19 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Confidentiality Can be in LOI or in a separate agreement Generally should not supersede existing NDA Prohibit public disclosure Governing law Usually not contentious But may set precedent for the purchase agreement Parties often choose Delaware or New York klgates.com 10 20 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Costs & Expenses Often parties agree to pay own fees Can be subject of negotiation Other expenses (HSR fee, etc.) Binding / Non-binding terms Critical provision LOI should generally be non-binding Expressly designate which provisions are binding Should be included in binding terms klgates.com 21 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Assignment Buyer should preserve flexibility to assign to affiliate Amendment Must be in writing Authority Parties have the authority to execute and perform No third-party beneficiaries Important if LOI references commitments with respect to employees or other third parties klgates.com 11 22 KEY LOI PROVISIONS Counterparts Provide for counterpart signature pages from parties Entire Agreement / Integration Supersede other negotiations / agreements Exceptions Expiration of LOI Offer Can range from one day to one week or longer Motivates seller to accept LOI quickly Avoid seller acceptance of “stale” LOI klgates.com 23 CONCLUSIONS LOI Benefits Help parties find consensus Create deal momentum Used with regulators, banks, insurers, etc. Create a sense of “moral commitment” LOI Disadvantages Time and resources Trigger disclosure requirements Inadvertent binding agreement klgates.com 12 24 13 NBI TELECONFERENCE LETTERS OF INTENT IN MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS: PRACTICAL TIPS FOR NEGOTIATING AND PREPARING JAMES SHARPE BRUCE 1 K&L GATES LLP I. Overview A letter of intent (an “LOI”) is a document entered into at a preliminary stage of a negotiated transaction, especially in connection with mergers and acquisitions. An LOI often takes the form of a formal letter from the buyer to the seller and generally sets forth certain preliminary terms of the deal. An LOI is not required for an M&A deal, although they are common in most deals (other than public company mergers) and can be useful in setting out the key terms of a transaction. However, as will be discussed in more detail below, there are several reasons or situations where an LOI is not necessary or recommended. An LOI is similar to, and may sometimes be referred to as, a “term sheet,” a “memorandum of understanding” or a “commitment letter.” For the most part, the points discussed below will also be applicable to these other documents, but there are some key differences. The terms of the LOI are often negotiated by the business side of the deal team – rather than among the lawyers – so that the attorneys’ first involvement in a deal may be after the LOI has been signed. However, if possible, the legal team should be actively involved in the drafting of the LOI. At the very least, attorneys should review and comment on the LOI before it is signed. Although most of the terms of an LOI are not intended to be legally binding, having the guidance of counsel during the negotiating and drafting of the letter can set the deal up for success and help clients avoid many common pitfalls. II. Purpose of a Letter of Intent An LOI summarizes the key terms of an M&A transaction. While it does not necessarily set out every detail of the deal, the LOI typically includes many of the material provisions. The 1 Mr. Bruce is a partner in the Corporate/M&A practice group of K&L Gates LLP and oversees the Corporate/M&A practice in the firm’s Charleston, SC office. Mr. Bruce gratefully acknowledges the assistance of his colleagues Will Grossenbacher, Nate Strickler and Claire Flowers in preparing these materials. © 2018 K&L Gates LLP. All rights reserved. 14 final agreement between the parties will be laid out in a formal, comprehensive negotiated agreement – generally an asset purchase agreement, a stock purchase agreement or a merger agreement (each referred to herein as a “purchase agreement”) – that will govern the transaction in its entirety. Once the definitive purchase agreement is executed, the terms of set forth in LOI will generally be superseded by the terms of the purchase agreement. The LOI nevertheless plays an integral role in guiding the deal negotiations throughout drafting of the purchase agreement. Additionally, in the event that the parties cannot reach a consensus and the purchase agreement is not signed, the binding terms in the LOI (such as confidentiality and expenses) will be even more crucial. A. Setting Initial Terms The main purpose of an LOI is to document the initial understanding of the parties with respect to the key terms of the deal. Even though the LOI is generally nonbinding and unenforceable with respect to the main deal terms, it is important in documenting the basic terms of the deal as the parties move toward a definitive agreement. The key to an effective LOI is to strike the appropriate balance between outlining sufficient details of the transaction and keeping the momentum of the deal progressing towards the purchase agreement. If the parties get bogged down in too many details in the LOI, they may simply abandon the transaction out of a belief that an agreement will ultimately be unreachable, or they may determine that it would be more efficient to move directly to a purchase agreement. On the other hand, if the LOI does not cover enough of the material terms, the parties may discover at a later stage of negotiation that there are fundamental disagreements that will prevent the parties from reaching a deal. B. Establishing a Roadmap Another important purpose of an LOI is to establish a framework or plan for the transaction. The LOI helps the parties work towards a final agreement by forcing both sides to come to terms on the key issues and identifying potential areas of conflict. By memorializing the key terms of the proposed purchase agreement, the parties reduce the chances for disagreement later. Finally, the LOI will often contain the preliminary schedule and deadlines for signing the purchase agreement and closing the deal. The LOI may also contain other deadlines, such as a period of exclusivity or a date by which the terms of the LOI must be accepted by the seller or they will expire. -2- 15 III. Advantages and Disadvantages It is important to note that an LOI is not necessary or desirable for every deal. Factors that ought to be considered in deciding whether to implement an LOI include: x the size and complexity of the deal; x timing of the transaction; x the desire for exclusivity; x disclosure requirements; x the necessary regulatory approvals required; x the amount of apparent leverage; and x the sophistication of the parties and their counsel. A relatively simple deal without an intense buyer bidding process may be best served by skipping the LOI entirely and focusing on the definitive purchase agreement. In some cases, negotiating an LOI could disrupt, rather than help, the deal flow, as well as create disclosure obligations for public companies under the securities laws. Ultimately, counsel must weigh whether the possible benefits of an LOI outweigh the costs, both in terms of time and resources, as well as deal disruption and reaching the client’s goals. IV. Buyer Interests A. Eliminate Competition Buyers typically prefer to enter into an LOI if they are able to achieve exclusivity and eliminate other bidders for some period of time. This may come in the form of a “no-shop” provision, whereby the seller is forbidden from marketing the business to prospective buyers for certain duration. This may also mean the seller is free to continue to field offers under certain conditions, such as providing the buyer with notice and copies of any other offers the seller receives. A buyer may also attempt to negotiate for some compensation from the seller should the seller move forward with another buyer. This could take the form of a break-up fee or a seller reimbursement of the expenses the buyer accrued during due diligence and negotiations, which can be substantial. -3- 16 B. Access to the Business Usually, a buyer has already been provided access to some information about seller’s business prior to the signing of the LOI. However, the LOI often ushers in the due diligence period where the buyer inspects the seller’s business to determine if it is worth purchasing at the proposed purchase price. The terms of the LOI will often govern the nature of the due diligence to be performed by the buyer, and in negotiating the LOI a buyer will be fighting for wide access to the business. A buyer’s goal is to learn as much about the seller’s business as possible to understand exactly what it is buying and to confirm buyer’s preliminary valuation of the business. This means the buyer will want broad access to contracts, books and records, real estate, customers, suppliers and employees. Particularly with respect to both customers and employees, the buyer wants to ascertain whether the business will operate as it did under the prior ownership by confirming that key customers and employees will not leave when their relationship with the prior owner ceases. Of course, the seller often resists providing this information to the buyer prior to the signing of a definitive purchase agreement to decrease the risk of disclosing sensitive information (in some cases to one of its competitors) in connection with a deal that does not ultimately close. On the other hand, a buyer is unlikely to purchase a business that it knows nothing about, so the seller must provide reasonable access to the business so the buyer can make an informed decision. C. Business as Usual Finally, a buyer will want certain operating covenants from the seller. If the seller knows the business is soon to be sold, its managerial rigor may become lax or it may seek to accelerate distributions or defer ordinary course maintenance. For this reason, the buyer will want the seller to agree to continue to operate the business up to certain standards or refrain from taking certain actions. For example, a seller may not be permitted to enter into certain material contracts without the consent of the buyer or the seller may not be able to make certain expenditures unless they are in the ordinary course of the seller’s business. Further, a seller may be prevented from taking certain actions, such as selling assets or issuing dividends that could cause the business to decrease in value. -4- 17 V. Seller Interests A. Capitalize on Leverage A seller generally wants to make sure that all material terms of the agreement are hammered out in the LOI. It is important to note that the seller’s strongest negotiating position is generally prior to the signing of the LOI, and the seller’s leverage typically diminishes precipitously after the LOI is signed. This is because the seller generally will not be able to market the business to other potential buyers for a period of time due to a “no-shop” provision contained in the LOI. Accordingly, after the signing of an LOI there is generally no longer a competitive bidding process with buyers competing as to both price and terms. This means the buyer can pressure the seller into making concessions it may not have otherwise made if it knew it could get better terms from another prospective buyer. Because the buyer is usually trying to get the LOI signed and achieve exclusivity, it is not uncommon for the seller to use this as leverage to get a more seller-favorable LOI. For example, the seller may attempt to negotiate for some type of break-up fee to be paid by the buyer in the event a definitive agreement is not reached. A buyer may be willing to risk a potential break-up fee for the benefit of eliminating competing prospective buyers. Similarly, a seller will want to nail down important terms, such as purchase price, escrow amounts and indemnification terms, in the LOI, when its bargaining power is strongest, as opposed to waiting to negotiate after the LOI when it may have substantially less leverage. B. Preserve the Business The seller also generally wants to delay for as long as possible, preferably until a definitive agreement is signed, the buyer’s ability to contact key customers and employees. The seller wants to create as little disruption as possible to the operation of the business in case the deal fails to close. Normally, this means the seller will try and keep the key employees and customers from knowing that the business is up for sale or that a deal may be imminent until there is a signed purchase agreement. One way to do this is to delay disclosure of, and limit the buyer’s access to, such customers and personnel. Of course, the buyer wants to get to know the key employees because they are often integral to the success of the business, and therefore an important aspect of the buyer’s diligence. The seller not only wants to prevent business disruption, it also wants to prevent a scenario where the transaction does not close, but the buyer -5- 18 has poached one or more its key employees. To prevent the latter, some LOIs will contain no hire/no solicitation provisions that preclude the buyer from attempting to draw employees away from the seller’s business. An LOI may also provide that seller will not disclose customer information until immediately prior to the signing of the purchase agreement. C. Protect Proprietary Information As noted above, the seller should also make sure that all the buyer and its affiliates are bound by a nondisclosure agreement either in the LOI or in a separate document. After the LOI is signed, the buyer will be conducting due diligence on the seller during which the buyer will have access to a plethora of non-public and proprietary information. Because of this, sellers often require buyers to enter into a separate confidentiality agreement prior to initial negotiations. This agreement should obligate the buyer to not only refrain from disseminating private information, but also return or destroy the information if the deal is not consummated. VI. Binding vs. Non-Binding A. No Binding Agreement One of the primary legal issues concerning LOIs is whether the letter is binding or nonbinding. In most cases, either the buyer or the seller, or both, do not want to be obligated to consummate a proposed sale before the parties have actually entered into a definitive purchase agreement. This means that the parties generally stipulate in the agreement that it is not binding (except with respect to certain provisions discussed below). In the event that negotiations fall apart, there is always the risk that one party will nonetheless attempt to enforce the terms established in the LOI. In order to avoid such claims to the greatest extent possible, the LOI should clearly state which provisions, if any, are to be binding on the parties. However, as discussed more fully below, the conduct of the parties in negotiating the transaction can also come into play in the event that the parties dispute the binding or non-binding nature of the agreement. B. Conduct Matters When Courts Consider Whether an LOI Is Binding If there is an intention that an agreement is not complete until reduced to a subsequent definitive purchase agreement, the general rule is that no binding contract exists. If the intent of the parties to be bound, or not to be bound, is clearly stated in the LOI, courts presumably give -6- 19 such intent effect. However, courts may look beyond the words of the LOI to the parties’ “real” intent. To do so, courts consider the parties’ surrounding conduct, both before and after the signing of the LOI. Because of this, parties should make always sure the LOI reflects reality and their conduct remains consistent. For example, in the widely cited case Texaco, Inc. v. Pennzoil Co., the Texas Court of Appeals upheld a jury award of $10.7 billion in damages after the seller backed out of a proposed sale, even though the parties had only entered into a memorandum of understanding that contemplated a more definitive agreement. 729 S.W.2d 768 (Tx. App. Ct. 1987). In reaching that conclusion, the court placed particular emphasis on the wording of a press release between the parties that indicated an intent to be bound, even though the memorandum of understanding did not contain such language. Additionally, even though the memorandum of understanding contained open terms (which were presumably to be settled in the definitive agreement), the court argued that these terms were largely perfunctory and not material to the agreement. While the language of the LOI and the parties’ intentions are the most important considerations that courts will consider in determining whether an LOI will be binding or nonbinding, the Second Circuit, applying New York law, has looked to other factors in its analysis. In Vacold, LLC v. Cerami, the court stated that preliminary agreements, such as LOIs, fall into one of two categories. 545 F.3d 114 (2d Cir. 2008). The first type of preliminary agreement is a fully binding agreement where the parties agree to all terms and require no further negotiation. The second type of preliminary agreement is where “the parties agree to certain major terms, but leave other terms open for further negotiation.” This type of preliminary agreement only obligates the parties to negotiate the open terms in good faith. The court looked to the context of the negotiations and determined that the parties fully intended and understood the letter agreement to be fully binding. The court also noted that the parties left open no major terms and that “there is a strong presumption against finding binding obligations in an agreement that includes open terms.” Another important consideration is to ensure that the LOI remains completely in effect until a formal deal is reached, no matter how close to a deal the parties think they are. In Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. McDavid, the parties had a non-binding LOI in place; however, it expired before a formal deal was made. 693 S.E.2d 873 (Ga. Ct. App. 2010). The principal negotiator for Turner stated that an extension of the LOI was not necessary because the parties -7- 20 were “very, very close to a deal.” Two weeks later Turner told McDavid on the phone, “We have a deal.” The court interpreted that statement as a binding oral contract, even though the LOI stated that all agreements must be executed in writing. The court found that the LOI provision that the parties express their intentions to be bound only by written agreement had expired when Turner’s representative told McDavid that he had a deal. The court further stated that a meeting of the minds of the parties on the material terms of the agreement had occurred at that point, which expressed both parties’ intent to be bound. Whether or not an LOI is considered binding or non-binding could depend on how the court characterizes the function of the LOI. In Copeland v. Baskin Robbins, U.S.A., the court drew a distinction between “a contract to negotiate the terms of an agreement” and an “agreement to agree.” 96 Cal. App. 4th 1251 (2002). The court held that when two parties are simply negotiating to potentially “form or modify a contract, neither party has an obligation to continue negotiating or negotiate in good faith.” However, if parties are under a contractual obligation to continue negotiating, then the covenant of good faith and fair dealing attaches. In this case, the court determined that the LOI constituted a contractual obligation to negotiate and that the damages should be measured by the injury the plaintiff suffered in relying on the defendant to negotiate in good faith. These damages could include out-of-pocket costs associated with conducting the negotiation as well as lost opportunity costs. The court was unwilling to award damages for lost expectations (profits) because “there is no way of knowing what the ultimate terms of the agreement would have been or even if there would have been an agreement.” C. Intentionally Binding Provisions Although most LOI provisions are typically intended to be non-binding, LOIs almost always contain some binding provisions. In most cases, provisions regarding the business terms of the deal (such as the purchase price) are non-binding and subject to continued negotiations. Binding provisions are usually limited to those that a party thinks necessary during the negotiation period. Common binding provisions include exclusivity, confidentiality, expenses, no third-party beneficiaries, and governing law. In some rare cases, the parties may make the entire LOI binding. If the party that wants a binding LOI has more bargaining power, the other party can agree to be bound if it is highly -8- 21 motivated to complete the deal. Parties must ensure that the LOI properly reflects their intentions. If the LOI includes provisions that are intended to be binding, these must be clearly identified and the legal requirements for creation of a valid contract must be satisfied (for example, the terms must be sufficiently certain and there must be consideration). The parties should be careful to include appropriate language to document the non-binding nature of the LOI provisions, because otherwise a court may find that the parties have entered into a binding agreement. This is more of a risk for the buyer who will generally be at a disadvantage if forced to acquire a target business on the basis of an LOI without the protections afforded by a full purchase agreement. VII. Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith - Surveying Case Law In the event of a dispute over the terms of an LOI, even if the court does not find that the parties intended the agreement to be binding, the court may impose a duty to negotiate in good faith that is distinct from a breach of contract claim. The existence of this duty does not necessarily require that the parties actually close a deal once negotiations have begun. Rather, the duty to negotiate in good faith imposes a duty on the parties to at least attempt to reach a deal. Failure to do so could result in reliance damages to the injured party. Notably, in a recent case, the Delaware Supreme Court ruled that expectation damages can be awarded if the court determines that the parties would have reached a deal but for the defendant’s breach of its duty to negotiate in good faith. SIGA Technologies, Inc. v. PharmAthene, Inc., 67 A.3d 330 (Del. 2013). Courts have not applied this duty uniformly. However, the states can generally be grouped into four categories as follows: (i) a court has affirmatively found that there is no duty to negotiate in good faith; (ii) a court has enforced a duty to negotiate in good faith if the LOI is binding or the LOI states such a duty; (iii) a court has imposed a duty to negotiate in good faith for preliminary agreements, such as non-binding LOIs; or (iv) courts applying that state’s laws have not addressed the issue. Based on these four categories, the current state of case law for each state is indicated in the table on Exhibit A attached hereto with citations where applicable. -9- 22 VIII. Advanced Strategic Negotiations A. Transaction Type The LOI should state both the subject and structure of the transaction. This means determining whether the purchase will be of stock or assets and whether the deal will be in the form of an acquisition or merger. For an asset purchase transaction, the parties may not know all the specific assets that will be purchased. In that event, the LOI should at least contain a general description of the assets or provide a mechanism for determining the assets (such as “all assets used or held for use in the business”). While big-picture deal terms such as these can (and often do) change after the LOI is agreed to, establishing these key terms early in the negotiation process is critical. With these terms outlined in the LOI, the parties can more efficiently negotiate and draft the purchase agreement pursuant to which they will actually consummate the transaction. While some transactions may be conducted between a single buyer on one side and a single seller on the other, other transactions can be more complex. As a general rule, the LOI should also identify the parties to the transaction, or, if the parties cannot be presently defined, then contain a reference to that fact. For a transaction structured as a stock purchase, this could mean listing the selling shareholders or providing a mechanism for determining the selling shareholders or at least identifying a shareholder representative. Additionally, in certain merger transactions, the acquiring entity may have not been formed as of the time of the signing of LOI. In that case, including additional information about the timeline for forming the acquisition subsidiary and additional information on the entity type (e.g. a Delaware limited liability company) will be useful in creating certainty and reducing to writing the various moving parts of the deal. B. Price The LOI should also set out the purchase price and whether the purchase price will be paid in cash, stock, via a promissory note, or a combination of methods. If all or a portion of the purchase price is to be paid with a promissory note from the buyer or in buyer stock, the LOI should reflect this. If a promissory note is to be issued, seller’s counsel should consider setting out the principal terms of the note (for example, unsecured or secured, interest rate, maturity date). There are typically a number of commercial and tax considerations that determine the - 10 - 23 nature and structure of the consideration. The tax consequences to the parties can vary depending on the type of consideration and the transaction structure, so counsel should consult a tax specialist before committing to any particular structure at this stage. If the purchase price is subject to any adjustment (such as a working capital adjustment), the LOI should reflect this. Until due diligence has been completed, the buyer is at a disadvantage in terms of knowledge about the business being sold. The buyer may or may not have received an information statement concerning the target business, and the preliminary information on which it based its valuation is not likely to include particularly sensitive contingencies or other material non-public information. It is possible that the purchase price reflected in the LOI may be negatively affected by the due diligence findings and a more thorough review of the target’s financial statements. In terms of establishing any adjustments, the LOI often states the general basis on which the purchase price was calculated and the assumptions considered by the buyer in determining the purchase price. This will provide the buyer with additional leverage if it wants to lower the purchase price if one of the assumptions proves false during the course of due diligence. Buyers use purchase price adjustments to protect themselves against decreases in the value of the target business (or a depletion of its working capital) during the period between the date of the most recent financial statements and the closing. Counsel to the buyer must confirm with the buyer that a working capital adjustment is appropriate for the proposed transaction. Alternatively, the buyer can include a purchase price adjustment based on something other than working capital, such as net worth, profits and losses, value of specific assets and EBITDA. In that case, appropriate changes must be made in this section although it is not necessary to fully document the mechanics of the desired adjustment. In drafting the LOI, it may be better to state the general principle of the adjustment rather than attempt to provide any detailed formula, calculations or definitions in the LOI itself. The LOI should also discuss whether a portion of the purchase price will be held in escrow to settle potential indemnification claims against the seller and other post-closing obligations. Also, if the parties agree to an earn-out, the seller may request that the buyer deposit some or all of the deferred consideration payments into escrow. In either case, if either party is considering an escrow, the general terms (such as, how much should be deposited into escrow and for how long) are often negotiated at this stage and incorporated into the LOI. The other - 11 - 24 details of the escrow will be negotiated when the purchase agreement and escrow agreement are drafted. C. Confidentiality An LOI generally contains commercially sensitive information, and the parties will want to ensure that the contents (and even the existence) of the document are confidential. Assuming a confidentiality agreement has already been entered into, the LOI should simply acknowledge that the information is confidential and make it clear that it is subject to the terms of the existing confidentiality agreement that will continue in full force and effect. The parties should confirm the terms of the confidentiality agreement to ensure that what is said in the LOI is consistent with the operative provisions of that agreement. If no confidentiality agreement has been entered into by the time the LOI is to be signed (or it is unclear whether the LOI will be treated as confidential information for the purpose of any confidentiality agreement), the parties should consider including a legally binding confidentiality provision in the LOI. D. Costs and Expenses An expense reimbursement provision can be included along with an exclusivity provision to further shift the risk that the transaction is not consummated onto the seller. An expense reimbursement provision requires the seller to pay the buyer’s legal and other transaction expenses if the seller decides not to proceed with the transaction, except in limited circumstances (mutual agreement, a material change in the offer terms or the buyer deciding not to proceed). This provision may be viewed as fairly aggressive at this stage of the transaction, but depending on the buyer’s leverage and its concerns about the seller’s commitment to agreeing to a definitive agreement and completing a transaction, it may be appropriate. Buyer’s counsel should expect resistance to this provision, which is similar to a break-up fee. Seller’s counsel will likely argue that the seller is also investing considerable time and expense (such as legal and financial advisors’ fees) in undertaking the proposed transaction and it therefore has demonstrated its commitment to seriously consider the transaction. If the buyer insists on an expense reimbursement provision, the seller can counter by requesting either a reciprocal expense reimbursement provision or that the buyer pay an exclusivity fee. Whether or not an expense reimbursement is included in the LOI will depend ultimately on the negotiating leverage of the parties. - 12 - 25 E. Exclusivity Another important function of an LOI is to establish the terms of exclusivity, if any, among the parties. The exclusivity provision acts as a way to shift some of the risk of negotiating the transaction and conducting due diligence onto the seller. The length of the exclusivity period can vary, ranging from a few weeks to a few months, depending on factors such as the complexity of the transaction, the amount of due diligence material to be reviewed, and the presence of other interested buyers. Thirty to sixty days are common exclusivity periods in LOIs. The most common means of enacting an exclusivity provision is through a no-shop provision. The no-shop seeks to prevent the seller from negotiating with, or soliciting offers from, other parties for a fixed period. It gives the buyer a period of exclusivity so that it can negotiate the definitive agreement with a view toward completing the proposed transaction. A comprehensive no shop provision requires the seller and its affiliates to terminate any pending discussions with any third parties and prohibits the seller group from entering into, soliciting or negotiating an alternative transaction for the duration of the exclusivity period. Restrictions such as these are fairly standard for exclusivity provisions. Exclusivity is frequently negotiated as a part of the LOI. Usually this is because the seller has chosen to preserve its leverage and not grant exclusivity to the buyer until it has negotiated the material terms of the transaction. Exclusivity provisions are common in LOIs because transactions can involve complex, expensive due diligence reviews and lengthy negotiations. A buyer often conditions its execution of the LOI on the seller agreeing to an exclusivity period. While exclusivity provisions are often included in an LOI, the parties can also negotiate and document exclusivity in a stand-alone agreement. The exclusivity provision should be one of the binding provisions in an LOI. To be enforceable, the seller’s obligation not to shop the deal must be supported by consideration. Generally, the consideration for having an exclusivity agreement is the time and expense incurred by the buyer in pursuing the proposed transaction. However, if there is doubt as to the sufficiency of this consideration, especially agreements with particularly long exclusivity periods, the buyer sometimes pays a fee in consideration for exclusivity. - 13 - 26 F. Termination An LOI should also include terms for how and when the parties can withdraw from the proposed transaction. One potential termination provision is a “financing out,” whereby the buyer is not longer obligated to consummate the transaction if it is unable to obtain financing. Including the availability of financing as a closing condition protects the buyer, but is a controversial provision. While sellers typically resist financing outs, a buyer may succeed in including one if it has significant leverage in the transaction. The buyer should be prepared for the seller to ask about the details of the financing (such as the amount needed, the stage of commitments and buyer’s history with financings and relationship with prospective lender or lenders). G. Break-up Fee The buyer may also seek to include a “break-up fee” provision that requires the seller to pay the buyer an agreed-upon amount in the event the seller sells the target to any other buyer within a specified time. The seller may also require a “reverse break-up fee,” whereby the buyer will be obligated to pay the seller should the transaction not close due to some condition not caused by the seller (such as buyer’s failure to secure financing). The logic for the seller, particularly sellers who may have multiple interested buyers, is that there is a potential opportunity cost for agreeing to exclusively negotiate with the buyer and that in the event that the buyer backs out, that cost should be accounted for. H. Due Diligence Requirements and Access to Information Another important consideration is the amount of access that the seller will give the buyer and its representatives to the records and key employees of the target business in order for the buyer to conduct its due diligence. Sellers will generally want to avoid giving unlimited access and a commitment to provide all information requested or deemed relevant by the buyer. This is because the due diligence process can be disruptive to the employees, customers and suppliers of the target business. Once employees and others become aware that a transaction in the works, it may be difficult for the seller to terminate discussions and resume business as usual if the seller decides not to go forward with the proposed deal. Additionally, open access to employees and information may be inconsistent with the approach set out in the relevant confidentiality agreement. There also may be regulatory or - 14 - 27 contractual limitations on the disclosure of information. For example, providing information that contains person data about employees may be subject to federal and state privacy and data security laws. Finally, if the parties are competitors, the seller may want to impose additional restrictions on disclosing materials. Competitors may be prohibited by law from sharing certain information (for example, pricing). Even if not prohibited by law, a seller may be wary about sharing information (such as customer names) before a closing is imminent. Nonetheless, from a buyer perspective, adequate access to information is crucial in determining whether the transaction is viable. At the same time, the buyer should be aware that its legal and financial teams will not have unlimited time to review the provided material, so the buyer should not sacrifice negotiating leverage to gain access to material it has no ability or intention to review. I. Expiration Date Buyer’s counsel usually includes a bid expiration date to motivate the seller to timely accept the terms of the LOI. Essentially the buyer is saying that if the LOI is not accepted by a date certain, the proposal is no longer valid. Counsel to the buyer should discuss with its client the appropriate date when the offer will expire. This period varies and can range anywhere from one day to one week or longer. Including an expiration date also protects the buyer from having a seller attempt to accept a stale LOI after negotiations have broken down. J. Governing Law Most LOIs do not need to contain overly detailed boilerplate provisions. In general, the parties should choose the law of a state that has a relationship to the parties or the proposed transaction (or there should be some other reasonable basis for the choice). The parties should also consider whether the choice of governing law for a preliminary agreement like the LOI will set a precedent for the choice of law for the purchase agreement. Many parties choose Delaware or New York as a neutral governing law because of their sophistication and well-established contract law. IX. Sample Letter of Intent Attached hereto as Exhibit B is a sample LOI that can be tailored for use in connection with an asset purchase transaction. This sample LOI is drafted from a buyer’s perspective and - 15 - 28 assumes, inter alia, that the transaction involves a single corporate buyer and a single corporate seller and that the buyer is purchasing substantially all of the assets of seller. This sample LOI also includes a number of other assumptions, including, without limitation, that (a) the consideration is in cash, with a portion being paid into escrow, (b) there is a working capital adjustment, (c) the signing and closing of the transaction will not be simultaneous, and (d) the parties have already entered into a confidentiality agreement. Buyer’s counsel should discuss the terms and utility of an LOI with the client prior to drafting the LOI and should carefully tailor the LOI to the specifics of a given transaction. X. Conclusions An LOI can be useful both for documenting points where the parties can easily find consensus, as well as identifying potential points that could derail the deal. It can also help provide the parties with a better sense of the potential timeline of the deal by laying out a staged schedule. Signing an LOI can provide both sides with momentum and increase the confidence of the parties that a final deal can be struck. It can also be used with regulators (e.g., Hart-ScottRodino filings), financiers, insurers, and others to help bring the deal to an eventual closing. Furthermore, an LOI can create a sense of “moral commitment” between the parties to work out their differences when negotiations stall to find a way to come to agreement. On the other hand, LOIs can take considerable time and resources and may not always justify the extra expense. A signed LOI can also potentially trigger public disclosure obligations, something one or both parties may wish to avoid at this juncture of the deal process. Also, by agreeing to an LOI at an early stage in the deal process, a party may hinder its ability to negotiate a better deal at a later time. Finally, while an LOI can be a useful tool to facilitate a transaction, if not properly drafted it can leave open the possibility that the parties have inadvertently created a binding agreement. * * * * * - 16 - 29 Exhibit A Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith State-By-State Survey State No Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith Imposed on Preliminary Agreements Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith when LOI is Binding or the LOI States a Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith Implied Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith for Preliminary Agreements, such as Non-Binding LOIs Have Not Addressed the Issue Alabama 9 Alaska 9 9 Arizona Arkansas FutureFuel Chemical Co. v. Lonza, Inc., 2012 WL 4049267 (E.D. Ark. Sept. 13, 2012). California Copeland v. Baskin Robbins, U.S.A., 96 Cal. App. 4th 1251 (2d Dist. 2002). 9 Colorado Connecticut Kopperl v. Bain, 2010 WL 3490980 (D. Conn. Aug. 30, 2010). Delaware SIGA Technologies, Inc. v. PharmAthene, Inc., 67 A.3d 330 (Del. 2013). District of Columbia Howard Town Center Developer, LLC v. Howard University, 278 F. Supp. 3d 333 (D.D.C. 2017). Florida Aldora Aluminum & Glass Products, Inc. v. Poma Glass & Specialty Windows, Inc., 683 F. App’x 764 (11th Cir. 2017). Georgia Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v. Thomas, 2011 WL 13234704 (N.D. Ga. Dec. 22, 2011). Hawaii 9 Idaho 9 A-1 30 State No Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith Imposed on Preliminary Agreements Illinois Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith when LOI is Binding or the LOI States a Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith Implied Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith for Preliminary Agreements, such as Non-Binding LOIs Have Not Addressed the Issue Midwest Mfg. Holding, LLC v. Donnelly Corp., 975 F. Supp. 1061 (N.D. Ill. 1997). Indiana 9 Iowa 9 Kansas 9 Kentucky Cinelli v. Ward, 997 S.W.2d 474 (Ct. App. Ky. 1998). Louisiana Beary v. Deese, 2017 WL 4791177 (E.D. La. Oct. 23, 2017). 9 Maine Maryland Phoenix Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Shady Grove Plaza Ltd. Partnership, 734 F. Supp. 1181 (D. Md. 1990). Massachusetts Schwanbeck v. FederalMogul Corp., 592 N.E.2d 1289 (Mass. 1992). Michigan Frazier Industries, L.L.C. v. General Fasteners Co., 137 F. App’x 723 (6th Cir. 2005). Minnesota C & S Acquisitions Corp. v. Northwest Aircraft, Inc., 153 F.3d 622 (8th Cir.). Mississippi 9 Missouri 9 Montana 9 Nebraska 9 9 Nevada New Hampshire Howtek, Inc. v. Relisys, 958 F. Supp. 46 (D.N.H. 1997). New Jersey Katsiavrias v. Cendant Corp., 2009 WL 872172 (D.N.J. March 30, 2009). 9 New Mexico A-2 31 State No Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith Imposed on Preliminary Agreements Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith when LOI is Binding or the LOI States a Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith New York Teachers Insurance and Annuity Ass’n of America v. Tribune, 670 F. Supp. 491 (S.D.N.Y. 1987). North Carolina TSC Research, LLC v. Bayer Chemicals Corp., 552 F. Supp. 2d 534 (M.D.N.C. 2008). Implied Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith for Preliminary Agreements, such as Non-Binding LOIs 9 North Dakota Ohio Nephrology & Hypertension Specialists, LLC v. Fresenius Medical Care Holdings, Inc., 2010 WL 3069758 (S.D. Ohio Aug. 5, 2010). 9 Oklahoma Oregon Logan v. Sivers, 169 P.3d 1255 (Or. 2007) (en banc). Pennsylvania Channel Home Centers, Div. of Grace Retail Corp. v. Grossman, 795 F.2d 291 (3d Cir. 1986). Rhode Island South Carolina Have Not Addressed the Issue Newharbor Partners, Inc. v. F.D. Rich Co., Inc., 961 F.2d 294 (1st Cir. 1992). Stevens & Wilkinson of S.C., Inc. v. City of Columbia, 762 S.E.2d 696 (2014). 9 South Dakota Tennessee Barnes & Robinson Co., Inc. v. OneSource Facility Services, Inc., 195 S.W.3d 637 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2006). Texas Karns v. Jalapeno Tree Holdings, LLC, 459 S.W.3d 683 (Tex. Ct. App. 2015). A-3 32 State Utah No Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith Imposed on Preliminary Agreements Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith when LOI is Binding or the LOI States a Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith Have Not Addressed the Issue King v. Nev. Elec. Inv. Co., 893 F. Supp. 1006 (D. Utah 1994). Vermont Sunnyside Cogeneration Associates v. Central Vermont Public Service Corp., 915 F. Supp. 675 (D. Vt. 1996). Virginia Beazer Homes Corp. v. VMIF/Anden Southbridge Venture, 235 F. Supp. 2d 485 (E.D. Va. 2002). Washington Commercial Development Co. v. Abitibi-Consolidated, Inc., 2008 WL 916951 (W.D. Wash. April 1, 2008). West Virginia Implied Duty to Negotiate in Good Faith for Preliminary Agreements, such as Non-Binding LOIs Akers v. Minnesota Life Ins. Co., 35 F. Supp. 3d 772 (S.D.W.V. 2014). Wisconsin 9 Wyoming 9 * * * * * A-4 33 Exhibit B Sample Letter of Intent for Asset Acquisition [BUYER LETTERHEAD] _____________, 2018 [SELLER AND ADDRESS] [_____________________] [_____________________] [_____________________] Dear [___________]: [BUYER], a [________] corporation (“Buyer”), is pleased to submit this letter (this “Letter”) to [SELLER], a [________] corporation (the “Company”), [and [STOCKHOLDER] (the “Stockholder”), the sole stockholder of the Company,] with respect to the proposed acquisition of substantially all of the assets of the Company by Buyer (the “Transaction”). This Letter of Intent is intended to summarize the principal terms and conditions of the Transaction and the present intentions of the parties. 1. Acquisition of Assets. Subject to the satisfaction of the conditions described in this Letter of Intent, Buyer would acquire substantially all of the assets of the Company (the “Assets”) at the closing of the Transaction, [except that Buyer will not purchase certain assets to be specified in the Purchase Agreement including the following: ____________]. 2. Assumption of Liabilities. Buyer would not assume any liabilities of the Company except for those obligations of the Company under certain assumed contracts and certain current liabilities reflected in the Net Working Capital Amount (as hereinafter defined) (the “Assumed Liabilities”). 3. Purchase Price. Subject to adjustment as provided below, based on information that Buyer has received to date, the purchase price for the Assets would be $_________________ (the “Purchase Price”). A portion of the Purchase Price in the amount of $_________ will be deposited in escrow for a period of _________ following the Closing (as defined below) to secure post-closing obligations of the Company. The Purchase Price assumes the Assets would be purchased free of any liens or encumbrances. Any long term debt or capitalized lease obligations (including the current portion thereof and any prepayment penalties B-1 34 or similar costs or expenses) giving rise to any such liens or encumbrances will be repaid in full at Closing out of the Purchase Price. 4. Net Working Capital Adjustment. The Purchase Price would be decreased dollarfor-dollar by the amount, if any, by which the Net Working Capital Amount set forth on an [audited] closing balance sheet reflecting the Assets and Assumed Liabilities is less than the target Net Working Capital Amount agreed to by the parties in the definitive purchase agreement. “Net Working Capital Amount” shall mean the book value of the current assets included in the Assets less the book value of the current liabilities included in the Assumed Liabilities. 5. Closing. The closing (the “Closing”) of the Transaction would occur on a date to be set pursuant to the terms of a definitive asset purchase agreement (the “Purchase Agreement”) to be executed by the parties hereto. 6. Due Diligence. The Company will afford to Buyer and its officers, employees, accountants, counsel and other authorized representatives full access to and the right to inspect, review and make copies of the assets, properties, books, contracts, commitments and records of the Company, view physical properties and communicate with key employees, customers and vendors of the Company. The Company will furnish promptly to Buyer such additional financial and operating data and other documents and information related to the Company as Buyer or its representatives may from time to time request. 7. Definitive Agreement. The objective of this Letter of Intent is to document the intention of the parties to seek to execute and consummate a Purchase Agreement. The obligation of the parties to enter into a definitive Purchase Agreement will be subject to the negotiation by the Company and Buyer of a mutually agreed upon form of such Purchase Agreement. The Purchase Agreement would contain, among other provisions, appropriate representations and warranties and indemnities of the Company and the Stockholder, closing conditions, noncompetition and nonsolicitation covenants and other matters reasonably required by Buyer and its counsel and mutually agreeable to all parties. 8. Conditions to Closing. The Purchase Agreement would contain customary conditions to each party’s obligation to close. In addition, the obligation of Buyer to close shall be conditioned upon [list closing conditions such as HSR or other regulatory approvals, material consents, employment agreements, etc.] 9. Conduct of Business. During the effectiveness of this Letter of Intent, the Company will conduct its business in the ordinary and usual course of business consistent with past and current practices, and will use its reasonable best efforts to (a) maintain and preserve intact the business organization and goodwill of the Company, (b) retain the services of key personnel and employees, and (c) maintain satisfactory relationships with all persons having B-2 35 business relationships with the Company (including customers and vendors). The Company will not (v) increase the compensation of or pay or accrue any bonus to any employee other than in accordance with past established practices both as to type and amounts without the consent of Buyer, (w) pay any dividends inconsistent with past practices, (x) commit to any material capital expenditures, (y) make any unusual purchases or commitments, or (z) enter into any material contract or agreement or engage in any transaction out of the ordinary course of business without prior consultation with Buyer. 10. Exclusivity. In consideration of Buyer’s commitment to expend time, effort and expense to evaluate the transactions contemplated hereby, the Company and the Stockholder hereby agree that all negotiations or discussions with third parties regarding the sale of all or any portion of the stock or any of the assets of the Company or any of its subsidiaries (other than sales of inventory in the ordinary course of business) (a “Sale”), if any, will immediately cease, and that neither the Company or any of its affiliates, the Stockholder nor their representatives will directly or indirectly solicit or respond to any solicitation from, or provide any information to, or otherwise enter into any discussions or negotiations with, or enter into any letter of intent, memorandum of agreement or other binding or non-binding agreement with, any person or entity regarding a Sale or any other transaction inconsistent with the transactions contemplated by this Letter of Intent. 11. Termination. This Letter of Intent will automatically terminate and be of no further force or effect upon the earlier of (a) execution of the definitive Purchase Agreement, and (b) 5:00 p.m. New York City time on _________, 2018; provided, however, that the obligations contained in Sections 12, 13, 14 and 16 shall survive such termination. The termination of this Letter of Intent shall not affect any rights any party hereto has with respect to the breach of this Letter of Intent by another party hereto prior to such termination. 12. No Disclosure. The parties agree that the existence of this Letter of Intent, all of its terms and the discussions of the parties regarding the transactions contemplated hereby will be kept confidential by the parties in accordance with the confidentiality agreement, dated _________, 2018, executed by the parties (the “Confidentiality Agreement”). Buyer, the Stockholder and the Company will not, and Buyer, the Stockholder and the Company will cause their representatives and affiliates not to, issue any press release or make any other public announcement relating to the transactions contemplated herein without the prior written consent of the other party, except that any party may make any disclosure required to be made by it under applicable law. Prior to issuing any press release or making any public announcement required under applicable law, the party issuing such press release or making such public announcement will give reasonable prior notice to the other party. 13. Governing Law. This Letter of Intent shall be governed and construed and enforced in accordance with the laws of the State of _________, without giving effect to any B-3 36 choice or conflict of law provision or rule that would cause the application of laws of any jurisdiction other than those of the State of __________. 14. Costs and Expenses. [The Company and Buyer will each pay one-half of the Hart-Scott-Rodino filing fee.] Each party will bear its own costs and expenses (including, without limitation, any investment banker’s, broker’s or finder’s fees and any attorney’s and accountant’s fees) incurred in connection with the execution and delivery of this Letter of Intent and the consummation of the transactions contemplated herein. 15. Non-Binding. It is understood that this Letter of Intent is intended only to state the present understandings and intentions of the parties with respect to the proposed acquisition of the Assets by Buyer. Notwithstanding the terms of this Letter of Intent, or any other past, present or future written or oral indications of assent or indications of results of negotiation or agreement to some or all matters then under negotiation, it is agreed that no party hereto (and no person or entity related to any such party) will be under any legal obligation with respect to the proposed transaction or any similar transaction, unless and until a formal and definitive Purchase Agreement has been executed and delivered by all parties intending to be bound; provided, however, that the obligations set forth in Sections 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16 hereof will be binding on Buyer, the Stockholder and the Company upon execution and delivery of this Letter of Intent in accordance with the terms hereof. 16. Miscellaneous. a. Assignment. This Letter of Intent may not be assigned by any party hereto, except that Buyer may assign this Letter of Intent to any affiliate. b. Amendment. This Letter of Intent may be amended only by a written agreement executed by all parties hereto. c. Authority. Each party hereto represents and warrants that it has full power and authority to execute, deliver and perform this Letter of Intent and that such execution, delivery and performance do not violate (or require disclosure to any third party under) any provision of any other agreement to which any party hereto is a party. d. No Third Party Beneficiaries. Nothing herein is intended or shall be construed to confer upon any person or entity other than the parties hereto and their successors or permitted assigns, any rights or remedies under or by reason of this Letter of Intent. e. Counterparts. This Letter of Intent may be executed in counterparts, each of which will be an original, but all of which together will constitute one and the same agreement. f. Entire Agreement. This Letter of Intent constitutes the entire agreement between Buyer and the Company with respect to the matters covered herein and B-4 37 supersedes any prior negotiations, understandings or agreements with respect to the matters contemplated hereby, other than the Confidentiality Agreement. If the foregoing proposal is satisfactory to the Company, please so indicate by executing and returning a copy of this letter to the undersigned on or before 5:00 p.m. New York City time on __________, 2018. This Letter of Intent shall expire and be of no further force and effect if not executed and returned to Buyer prior to such time. Sincerely, [BUYER] By:_______________________________ Name: ____________________ Title: _____________________ Agreed to and accepted this ___ day of __________, 2018 by: [THE COMPANY] By:___________________________ Name:_________________ Title: _________________ [THE STOCKHOLDER] By:___________________________ Name:_________________ Title: _________________ B-5 38 Thank You for choosing NBI for your continuing education needs. Please visit our website at www.nbi-sems.com for a complete list of upcoming learning opportunities. 39