From

Scribblesto

Symbols

84-ye8r-old Michele draws a picture, a wide grin spreads How children

across lier face. She looks up from the tahle, her eyes

learn to draw

sparkling, and says, "Look, Dad, my lines look like

mountains!" As Michele moves her crayon way up and write—

on the page and then way down, creating a zigzag and what their

panern, she clearly delights in exploring the possi- pictures and

bilities of the lines she's forming.

stories tell you

Art is a language. It's a way that people—especially children—express ideas and feelings. In by Ellen Booth Church

many ways, art is the "first language" of the beginning reader and writer. Children use their inner photographs by

experiences to create art. Through their initial Frank Heckers

scribbles and imaginative drawings, they create

their own magical worlds, which help them make

sense of the real world around them. What does a tree look

like? How can I show what I see?

Children usually Ix'gin to draw and paint before they learn to

write. Their piaures are like words for them and mark an essential step on the road to literacy. They use what might look like

mere scribbles, lines, and blobs to represent what they see.

Amazingly, children can read these markings. You may have experienced your child "reading" her drawing to you, and then

going to the next person and reading it to them in the same way!

Unfortunately, we are finding that children at younger and

APRIL/MAY 20DS SCHOLASTIC PARENT a CHILD

41

younger ages are heing asked to

trace letters repeatedly and make

them ''fit" within lines. Yet scribbling is a wonderfully heartfelt expression of thoughts, images, and

emotions. Allowing children plent)'

of time to play with the lines,

shapes, and squiggles of scribbling

encourages interest in writing and

art. Best of all, children who engage

in plenty of scribbling are developing fine motor skills, eye-hand

coordination, and the creative confidence that will be so needed in

their later schooling.

Over time, chiidren learn to connect what they create to what the

shapes and figures represent, which

leads to the realization that symbols

stand in for other things. Understanding symbolic representation

helps children grasp that letters and

nil in bers signify something important. Both art and writing involve

making symbols.

When it comes to children's art

and writing, nothing rings truer

rhan the expression "It's the

prtKess, not the product." Children

Iearn how to think and solve problems from the free exploration of

art materials and language. Giving

your child time to express herself

through art and writing and talking

about artistic expression will help

her develop communication skills

and a deeper understanding of her

inner and outer worlds.

Put Feelings into Art

If you've ever asked your child how

she feeis, the answer is often simple:

She'll say "good" or "bad." While

most children have a huge vocabulary to describe their experiences,

they often don't have the words to

describe their feelings. Art is the

perfect outlet for your child's emotions. When creative expression is

not planned or directed into a particular projea, children can express

rheir feelings through a variety of

isplaying your child's

artwork at home [here

with clothespins and

wire) demonstrates your

pride and admiration.

media. A lump of clay or a brush

and paper allows children to express joy and happiness, and work

through sadness, feat; or anger with

artistic movements. Pounding the

clay or making sweeping strokes

with a paintbrush can offer a muchneeded release for a child who is

having a hard day.

Sometimes color is the significant part of your child's emotional

experiment with art. Children may

choose a particular color to express

an emotion—perhaps bright colors

to express happiness and dark,

murky colors to express confusion

or sadness. How the colors are put

on the page is usually even more

telling. Watch your child's brush or

crayon strokes. You can quickly

recognize the difference between a

gentle, peaceful movement and an

angry thrusting motion.

It's important not to jump to

conclusions, though. Just because

your child uses lots of black doesn't

necessarily mean she is angry or depressed. She may just like black for

its opaque quality, the way it covers

everything else. After one preschooler had been using only black

for weeks, her teacher gently asked

about it; "i noticed you are using a

lot of black in your pictures. What

do you like about the color?" The

child answered, "It's the color of

my new kitten! She's shiny and

makes me happy."

Help your child explore her

emotions more deeply by varying

the type and color of the paints and

tools you provide, as well as the

paper and objects to paint on

(boxes, rocks, fabric, for example).

Remember that emotions also have

texture. Supply small pieces of differently textured materials for her

to use. Mix a tiny bit of white glue

into the paint so that your child can

stick the bits right onto her paintings for a collage effect.

You can further expand your

child's artistic and emotional

growth by introducing "emotional"

vocabulary words. Use a variety of

words to describe how you feel. For

example, instead of saying you are

happy, say you are glad, joyful, or

merry. Instead of saying you had a

bad day, say you are frustrated or

weary. Children pick up words easily in context and will very quickly

start using them appropriately. Naturally, you can use these same

words when talking with your child

about her art.

Seeing with

an Artist's Eye

Art is perspective—seeing things a

certain way. Children are very good

at looking at the world in different

and unusual ways. In fact, their art

and writing are always a unique reflection, perfectly their own, which

makes them natural artists! And

that's something you can encourage by pointing out interesting

ways of seeing things. (See "Art Is

Seeing ..." on the next page.)

Inviting children to discuss their

work strengthens this connection

between pictures and words. Fouryear-old Alyssa was fascinated by a

rainbow she saw in a puddle. After

she made a rainbow at home with

her watercolors, her mom asked,

"What do you think makes rainbows?" Alyssa said, "Rainbows are

in puddles because they fell out of

the sky with the rain."

Introducing children to the work

of great artists is one of the best

ways to get them more interested in

artistic expression—and vision.

(Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, Henri

Matisse, Jackson Pollack, and Joan

Miro are all good starting places.!

Your child may be surprised to see

that many valued works of art are

similar to her own beginning drawings. Explain that artists have a

style. As she comes to realize that

artists don't always draw or paint

recognizable things, she'll feel less pressure

to draw something that looks perfect.

When you invite your child to look at

the work with an artist's eye, you open

the door for her to understand what the

artist is expressing. Talking about what

another artist might be thinking, feeling,

and trying to say sets the stage for her to

talk about her own work.

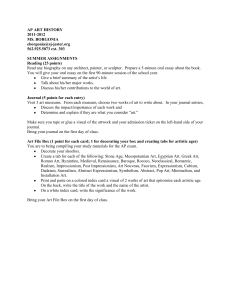

Let kids find

theirown style.

As you show your child a work of

modem art, invite her to suggest a title for

it—another way to connect art and language. Emphasize that there is no right

answer. For example, 5-year-old Omari

titled Mondrian's Broadway BoogieWoogie "Dancing Lines." and his friend

Marcy was surprised to learn that a Joan

Miro painting was titled People and Dog

in Sun. To her, it looked like "Kids Playing on the Swings."

How to Talk to Your Child

About Her Work

Unfortunately, one of the biggest problems with art in the early years is the wide

difference m children's artistic abilities. It

is not unusual for some children in the

same age group to be scribbling while

others are creating true representational

drawings that begin to look like people,

plants, and things.

When talking to your child about her

artwork, be sensitive and open. Consider

these points:

Tnf to avoid general compliments ("That's

pretty!"); judgments ('i really like what

you painted!"); corrections ("Nice picture, but remember that dogs have four

legs."); and direct questions ("What did

vou draw?").

Art Is Seeing...

Shapes in the clouds

Texture throughtlie trees

Lines on the buildings

Forms in the dark

Beauty in everyday things

Don't respondrightaway. By first smiling

and nodding when your child shows you

her work, you give her the chance to say

what she wants to say about it.

Simply say "Thank you!' The power of

those two little words is amazing, and

says so much: Thank you for making this

picture, for showing me, for working so

hard on it. There is no judgment, just a

sincere gratitude for the artistic effort.

Describe what you see. Say, "You used

many colors and some of them have

mixed together to make new ones!" Or

say, "I notice you made lines across the

bottom of the page." This opens the door

for your child to tell you something more

about the elements you are describing.

Encouraging

Self-Expression

Helping your child make the conneCTion

between art and writing starts with

time—and space—to experiment. Even if

space is tight in your home, try to set

aside a corner or table for your child's

artistic endeavors. Provide plenty of tools

and materials, such as washable paints,

crayons, glue sticks, child-safe scissors,

and paper. (See the story "An Center," on

page 68, for more ideas.)

Here are some easy activities that will

inspire your young artist:

Introduce the elements of art. Use "art

words" to teach her about the basics of

art: color (names of shades, light and

dark); shape (circle, square, triangle); texture {bumpy, smooth, fuzzy, lumpy); line

(long, short, straight, curvy, thick, thin,

spiral, slanted); and space (front, back,

high, low, near, far).

Use the internet to explore great art. You

can access images online by going to

google.com, clicking on Images, and typing in tbe artist's name. You'll quickly get

Symbols soon

emerge from

5cribbie5.

Use an old or new picture frame (posterstyle Plexiglas frames work well). Once a

month (or week!), ask your child to

choose a piece she wants to celebrate.

You can also string a clothesline across a

wall and hang her work witb clothespins.

Use a scanner to scan your child's art and

create cards for friends and relatives.

Create a portfolio. In addition to drawings, save your child's accompanying

words and dictation. Periodically, review

the portfolio so she can see how she has

grown. Involve your child in selecting the

work to save. Look for magnetic photo

albums to hold the art.

When young children experiment

with art, in any form, tbeir creative expression, language, and communication

skills blossom. Art is an outlet for emotions and a fertile ground for new ideas

to take form and flight. Swirls of color,

joyous or brooding; forgiving lumps of

clay to be molded and pounded; or any

material that can be shaped by imagination is a refuge.

some mini snapshots of the artist's work. "message" is revealed when it is held up

Simply click on the small version to en- to the heat of a lamp or in the sun!

Dispiay and share your child's art. As a Ellvn Booth Church is an earty childhood consuttani

large and then print it.

author Some of the activities in this story have

special

way to honor your child's work, and

Put a spin on paint-blot art. Ask your

been excerpted from her new book, 25 Literacychild to pick up thin tempera paint with frame it and hang it in the living room. Building Art Activities (Scholastic).

an eyedropper and drip it onto paper. Repeat with another color. Place plastic

wrap over her paper and invite her to

press it gently. The paints will blend and

swirl into interesting images that keep

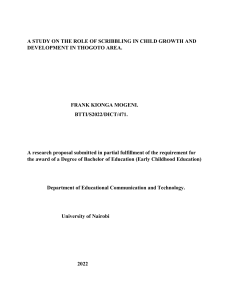

AGE

WHAT KIDS 00

STAGE

changing as your child moves her fingers

• Take great pleasure in moving a crayon over paper

over the plastic wrap. Remove the plastic

• Become interested in the page when they notice

wrap and set the painting aside to dry.

Random

to

their movements result in drawings

Scribbling

Make a book of dreams and wishes. Art

•

By age 2, may start to label their scribbles

and writing intersect in this handmade

project. What does your child usually

• Many 3s manipulate materials with a more purdream about? What does she wish for?

poseful action, as in "controlled scribbling"

Whenever your child remembers a

Pre

symbol

ism

•

By

age 4, children may attempt to represent the

to

dream, she can add drawings and words

human form with simple figures—mostly heads

to tell the story of her dream or wish. Try

with legs and arms

using lots of differently textured papers.

Punch holes on the sides of the pages and

• Begin creating simple representational drawings

store them in a binder. Glue a photo of

[self-portraits, pets, and family] with more details

your child on the cover.

Symboiism

• Have more control over the lines they draw

to

Make Invisible ink! Kids will love this

• May use the letters of their name [or other letters

science-inspired trick. With a paintbrush,

they know) repeatedly to write a message

your child can draw or write with lemon

juice or white vinegar on white paper. The

The Process of Learning to Draw and Write

1

2

3

4

5

6