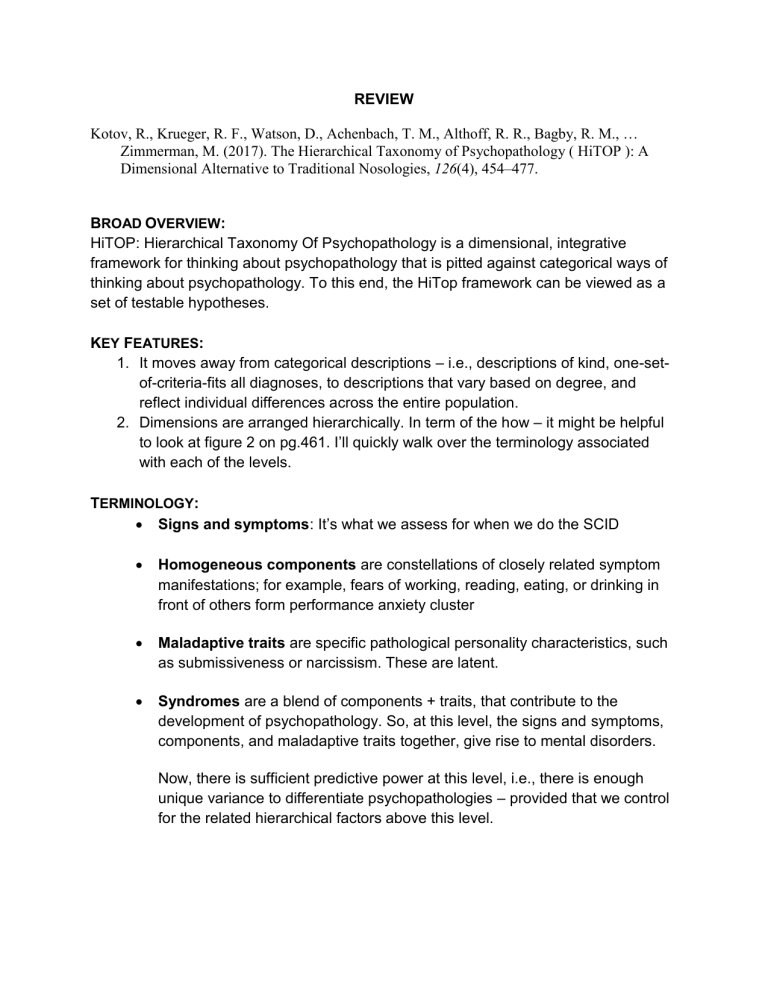

REVIEW Kotov, R., Krueger, R. F., Watson, D., Achenbach, T. M., Althoff, R. R., Bagby, R. M., … Zimmerman, M. (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology ( HiTOP ): A Dimensional Alternative to Traditional Nosologies, 126(4), 454–477. BROAD OVERVIEW: HiTOP: Hierarchical Taxonomy Of Psychopathology is a dimensional, integrative framework for thinking about psychopathology that is pitted against categorical ways of thinking about psychopathology. To this end, the HiTop framework can be viewed as a set of testable hypotheses. KEY FEATURES: 1. It moves away from categorical descriptions – i.e., descriptions of kind, one-setof-criteria-fits all diagnoses, to descriptions that vary based on degree, and reflect individual differences across the entire population. 2. Dimensions are arranged hierarchically. In term of the how – it might be helpful to look at figure 2 on pg.461. I’ll quickly walk over the terminology associated with each of the levels. TERMINOLOGY: Signs and symptoms: It’s what we assess for when we do the SCID Homogeneous components are constellations of closely related symptom manifestations; for example, fears of working, reading, eating, or drinking in front of others form performance anxiety cluster Maladaptive traits are specific pathological personality characteristics, such as submissiveness or narcissism. These are latent. Syndromes are a blend of components + traits, that contribute to the development of psychopathology. So, at this level, the signs and symptoms, components, and maladaptive traits together, give rise to mental disorders. Now, there is sufficient predictive power at this level, i.e., there is enough unique variance to differentiate psychopathologies – provided that we control for the related hierarchical factors above this level. Subfactors are groups of closely related syndromes; so, in this figure, all the phobias, OCD, and panic disorder are related to the Fear subfactor. Similarly, MDD, GAD, PTSD, BPD are explained by the Distress subfactor. So, now going back to syndromes: if I wanted information unique to say, MDD, I would statistically control for the variance explained by the “Distress” subfactor and then account only for the variance associated with MDD that is coming from signs and symptoms, homogenous components, and maladaptive traits. Anomalies: Panic disorder appears to have features of both fear and distress and has been found to load on both subfactors. Also, OCD is a relatively weak member of the fear cluster and shows some overlap with the thought disorder dimension. Spectra are larger constellations of syndromes, such as an internalizing spectrum composed of syndromes from fear, distress, eating pathology, and sexual problems subfactors. Spectra are an answer to the “classic problem” of co-occurring mental disorders, since they account for comorbidity between disorders. Anomalies: At present, it is unclear whether the mania subfactor belongs to the internalizing or thought disorder spec- trum or blends features of both (see Superspectra are extremely broad dimensions comprised of multiple spectra, such as a general factor of psychopathology (p; Caspi, 2014) that represents the liability shared by all mental disorders. LIMITATION OF CURRENT TAXONOMIES Categories seek to “carve nature at its joints”. Imposition of artificial categories in naturally dimensional phenomena. As a result of forceful categorization, there is loss of information. Test-retest reliability is poor, since “carving nature at its joints” is based on what makes sense. HOW HiTOP HANDLES THEM Does not rest on the assumption that mental disorders ate categorical; no loss of info. Test-retest reliability is high; based on structural model evidence. Is not able to explain transdiagnostic conditions and co-occurring disorders satisfactorily. Individual at subthreshold? At best, an NOS diagnosis. By virtue of a shared-covariance hierarchical model, co-occurring disorders are readily explained. Everyone is included! METHODS: (i) EFA and CFA to test the fit of hypothesized structures to data (ii) Class-based models. E.g. latent variable analysis. Not particularly useful since it identifies only extreme dimensions – i.e., suitable if interest is in someone who is severely depressed (so severe MDD diagnosis) or someone with very mild depression (mild MDD). (iii) Advocate for factor mixture models APPLICATION TO CLINICAL SETTINGS: 1. Go for ranges: Just like you have ranges of blood pressur or fasting glucose, provide ranges description of psychopathology, rather than a clear cut-off. Significant advances in the case of intellectual disability where ranges of intelligence and flexibility in adaptive functioning are used as diagnostic descriptors for intellectual disability. INTERFACE WITH RDoC: RDoC: Bottom-Up; biologically driven HiTOP: More top-down Let’s find a meeting ground; integrate top-down and bottom-up approaches. SPECTRA: CLINICAL: The internalizing dimension accounts for the comorbidity among depressive, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and eating disorders, as well as sexual dysfunctions and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). The externalizing dimension captures comorbidity among substance use disorders, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder, adult antisocial behavior, intermittent explosive disorder (IED), and attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). More recently, a thought disorder spectrum was identified, which encompasses psychotic disorders, cluster A PDs, and bipolar I disorder. Finally, initial evidence suggests existence of an additional somatoform spectrum SPECTRA: PERSONALITY: Goal is to explicate personality organization using factor analysis across different operationalizations of personality. Consistent results indicating five domains: negative affectivity, psychoticism, disinhibition, antagonism, and detachment (i.e., social withdrawal). For example, negative affectivity would be a common theme for dependent, avoidant, and borderline PDs. W.r.t. the FFM operationalization of personality, NA maps onto neuroticism. Similarly, antisocial, narcissistic, histrionic, borderline and paranoid PDs likely reflect antagonism. W.r.t. FFM operationalization of personality, antagonism maps onto low agreeableness. Cross-Talk: Joint Structures See figure 1. HIERARCHY ABOVE SPECTRA: The HiTOP spectra are positively correlated. and these associations are consistent with the existence of a general psychopathology factor or p factor. AT THE LEVEL OF SYMPTOM STRUCTURE: Word of advice: Watch out for skip-logic: Skip logic like in the SCID can result in incomplete symptom data for respondents who do not endorse the stem question. See figure 3, for symptom components and maladaptive traits organized by spectrum. Brief discussion of different questionnaires that capture at least 2 levels of the hierarchy (e.g., Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS)). Applications of quantitative classification versus one based on “that make’s sense” 1. Genetic studies concur with HiTOP model; factor analytically derived spectra appear to reflect common genetic vulnerabilities. 2. Common environmental risk factors shape the spectra -e.g., discrimination and childhood maltreatment are linked much more closely to spectra than to unique aspects of disorders. 3. Neurobiological abnormalities may show clearer and stronger links to the HiTOP dimensions than to traditional diagnostic categories, because empirically derived dimensions offer greater informational value and specificity. For example, Nelson, distress subfactors are associated with blunted neural reactivity to all stimuli, whereas fear subfactors are associated with enhanced reactivity to negative stimuli. 4. Fourth, quantitative dimensions can effectively capture illness course. Categorical outcomes such as remission and recovery are controversial as they lack natural benchmarks. In contrast, dimensions can characterize the outcome at every level of psychopathology from severe impairment to subthreshold symptoms to full recovery. 5. A quantitative organization may explain and predict the efficacy of treatments, including limited diagnostic specificity of treatment response observed for many interventions. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors originally were regarded as antidepressants but subsequently were found to be efficacious in treating anxiety disorders and are increasingly used in eating disorders. Transdiagnostic cognitive–behavioral therapy and even disorderspecific psychotherapies have been found to reduce symptoms of various internalizing conditions. Comments: Eiko Fried: “Psychopathological symptoms are inter-related in complex ways. What I am missing is a discussion about the assumption that identified underlying constructs cause the covariance among symptoms. Besides, what does it actually mean that the internalizing factor causes the internalizing symptoms? What is the internalizing factor in the world? These are important questions if we want to move the field of psychopathology research forward. The two approaches described above are not everything the field has to offer, an alternative notion has emerged a few years ago that also explains why some symptoms co-occur more than others. It does not posit mystic latent entities that everybody assumes but nobody talks about. The covariance among symptoms is not due to a common cause, but due to mutual interactions in a dynamic complex system. Depression is a good example, where certain symptoms seem to occur together quite often. From the perspective of networks, insomnia causes fatigue which triggers psychomotor and concentration problems, instead of a latent factor depression (whatever that is) causing these symptoms. I am not suggesting the network approach as a superior solution here that is without difficulties, but merely for the sake of having all options that explain symptom covariance on the table.”