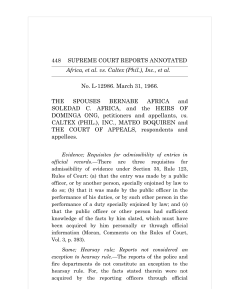

Agency Case Digests Nielson v. Lepanto Issue: Whether the management contract is a contract of agency or a contract of lease services Held: Article 1709 of the Old Civil Code, defining contract of agency, provides that "By the contract of agency, one person binds himself to render some service or do something for the account or at the request of another." Article 1544, defining contract of lease of service, provides that "In a lease of work or services, one of the parties binds himself to make or construct something or to render a service to the other for a price certain." In both agency and lease of services one of the parties binds himself to render some service to the other party. Agency, however, is distinguished from lease of work or services in that the basis of agency is representation, while in the lease of work or services the basis is employment. The lessor of services does not represent his employer, while the agent represents his principal. Further, agency is a preparatory contract, as agency "does not stop with the agency because the purpose is to enter into other contracts." The most characteristic feature of an agency relationship is the agent's power to bring about business relations between his principal and third persons. "The agent is destined to execute juridical acts (creation, modification or extinction of relations with third parties). Lease of services contemplate only material (non-juridical) acts." Herein, the principal and paramount undertaking of Nielson under the management contract was the operation and development of the mine and the operation of the mill. All the other undertakings mentioned in the contract are necessary or incidental to the principal undertaking — these other undertakings being dependent upon the work on the development of the mine and the operation of the mill. In the performance of this principal undertaking Nielson was not in any way executing juridical acts for Lepanto, destined to create, modify or extinguish business relations between Lepanto and third persons. In other words, in performing its principal undertaking Nielson was not acting as an agent of Lepanto, in the sense that the term agent is interpreted under the law of agency, but as one who was performing material acts for an employer, for a compensation. It is true that the management contract provides that Nielson would also act as purchasing agent of supplies and enter into contracts regarding the sale of mineral, but the contract also provides that Nielson could not make any purchase, or sell the minerals, without the prior approval of Lepanto. It is clear, therefore, that even in these cases Nielson could not execute juridical acts which would bind Lepanto without first securing the approval of Lepanto. Nielson, then, was to act only as an intermediary, not as an agent. Further, from the statements in the annual report for 1936, and from the provision of paragraph XI of the Management contract, that the employment by Lepanto of Nielson to operate and manage its mines was principally in consideration of the know-how and technical services that Nielson offered Lepanto. The contract thus entered into pursuant to the offer made by Nielson and accepted by Lepanto was a "detailed operating contract". It was not a contract of agency. Nowhere in the record is it shown that Lepanto considered Nielson as its agent and that Lepanto terminated the management contract because it had lost its trust and confidence in Nielso “Quote” 2 Dela Cruz v. Northern Theatrical Issue: Plaintiff De la Cruz is considered as an agent of the corporation and as such entitled to reimbursement for expenses incurred in connection with agency Held: No, Plaintiff is mere employee. The relationship between the movie corporation and plaintiff was not that of principal and agent because the principle of representation as a characteristic of agency was in no way involved. Plaintiff was not employed to represent corporation in its dealings with 3rd parties. Plaintiff is a mere employee hired to perform a certain specific duty or task, that of acting as a special guard and staying at the main entrance of the movie house to stop gate crashers and to maintain peace and order within the premises Fressel v. Uy Chaco Sons & Co. Issue: a Held: Where the contract entered into is one where the individual undertook and agreed to build for the other party a costly edifice, the underlying contract is one for a contract for a piece of work, and not a principal and agency relation. Consequently, the contract is authorized to do the work according to his own method and without being subject to the client's control, except as to the result of the work; he could purchase his materials and supplies from whom he pleased and at such prices as he desired to pay. And the mere fact that it was stipulated in the contract that the client could take possession of the work site upon the happening of specified contingencies did not make the relation into that of an agency. Consequently, when the client did take over the unfinished works, he did not assume any direct liability to the suppliers of the contractor. 3 Shell Co. v. Firemen’s Insurance Issue: The next issue is whether Caltex should be held liable for the damages caused to appellants. Held: This issue depends on whether Boquiren was an independent contractor, as held by the Court of Appeals, or an agent of Caltex. This question, in the light of the facts not controverted, is one of law and hence may be passed upon by this Court. These facts are: (1) Boquiren made an admission that he was an agent of Caltex; (2) at the time of the fire Caltex owned the gasoline station and all the equipment therein; (3) Caltex exercised control over Boquiren in the management of the state; (4) the delivery truck used in delivering gasoline to the station had the name of CALTEX painted on it; and (5) the license to store gasoline at the station was in the name of Caltex, which paid the license fees. In Boquiren's amended answer to the second amended complaint, he denied that he directed one of his drivers to remove gasoline from the truck into the tank and alleged that the "alleged driver, if one there was, was not in his employ, the driver being an employee of the Caltex (Phil.) Inc. and/or the owners of the gasoline station." It is true that Boquiren later on amended his answer, and that among the changes was one to the effect that he was not acting as agent of Caltex. But then again, in his motion to dismiss appellants' second amended complaint the ground alleged was that it stated no cause of action since under the allegations thereof he was merely acting as agent of Caltex, such that he could not have incurred personal liability. A motion to dismiss on this ground is deemed to be an admission of the facts alleged in the complaint. Caltex admits that it owned the gasoline station as well as the equipment therein, but claims that the business conducted at the service station in question was owned and operated by Boquiren. But Caltex did not present any contract with Boquiren that would reveal the nature of their relationship at the time of the fire. There must have been one in existence at that time. Instead, what was presented was a license agreement manifestly tailored for purposes of this case, since it was entered into shortly before the expiration of the one-year period it was intended to operate. This so-called license agreement (Exhibit 5Caltex) was executed on November 29, 1948, but made effective as of January 1, 1948 so as to cover the date of the fire, namely, March 18, 1948. This retroactivity provision is quite significant, and gives rise to the conclusion that it was designed precisely to free Caltex from any responsibility with respect to the fire, as shown by the clause that Caltex "shall not be liable for any injury to person or property while in the property herein licensed, it being understood and agreed that LICENSEE (Boquiren) is not an employee, representative or agent of LICENSOR (Caltex)." But even if the license agreement were to govern, Boquiren can hardly be considered an independent contractor. Under that agreement Boquiren would pay Caltex the purely nominal sum of P1.00 for the use of the premises and all the equipment therein. He could sell only Caltex Products. Maintenance of the station and its equipment was subject to the approval, in other words control, of Caltex. Boquiren could not assign or transfer his rights as licensee without the consent of Caltex. The license agreement was supposed to be from January 1, 1948 to December 31, 1948, and thereafter until terminated by Caltex upon two days prior written notice. Caltex could at any time cancel and terminate the agreement in case Boquiren ceased to sell Caltex products, or did not conduct the business with due diligence, in the judgment of Caltex. Termination 4 of the contract was therefore a right granted only to Caltex but not to Boquiren. These provisions of the contract show the extent of the control of Caltex over Boquiren. The control was such that the latter was virtually an employee of the former. Taking into consideration the fact that the operator owed his position to the company and the latter could remove him or terminate his services at will; that the service station belonged to the company and bore its tradename and the operator sold only the products of the company; that the equipment used by the operator belonged to the company and were just loaned to the operator and the company took charge of their repair and maintenance; that an employee of the company supervised the operator and conducted periodic inspection of the company's gasoline and service station; that the price of the products sold by the operator was fixed by the company and not by the operator; and that the receipts signed by the operator indicated that he was a mere agent, the finding of the Court of Appeals that the operator was an agent of the company and not an independent contractor should not be disturbed. To determine the nature of a contract courts do not have or are not bound to rely upon the name or title given it by the contracting parties, should thereby a controversy as to what they really had intended to enter into, but the way the contracting parties do or perform their respective obligations stipulated or agreed upon may be shown and inquired into, and should such performance conflict with the name or title given the contract by the parties, the former must prevail over the latter. (Shell Company of the Philippines, Ltd. vs. Firemens' Insurance Company of Newark, New Jersey, 100 Phil. 757). The written contract was apparently drawn for the purpose of creating the apparent relationship of employer and independent contractor, and of avoiding liability for the negligence of the employees about the station; but the company was not satisfied to allow such relationship to exist. The evidence shows that it immediately assumed control, and proceeded to direct the method by which the work contracted for should be performed. By reserving the right to terminate the contract at will, it retained the means of compelling submission to its orders. Having elected to assume control and to direct the means and methods by which the work has to be performed, it must be held liable for the negligence of those performing service under its direction. We think the evidence was sufficient to sustain the verdict of the jury. (Gulf Refining Company v. Rogers, 57 S.W. 2d, 183). Caltex further argues that the gasoline stored in the station belonged to Boquiren. But no cash invoices were presented to show that Boquiren had bought said gasoline from Caltex. Neither was there a sales contract to prove the same. Dela Peña v. Hidalgo Issue: W/N Hidalgo is considered an agent of Gomiz and as such must reimburse present administrator, De la Pena Held: No 5 Gomiz, before embarking for Spain, executed before a notary a power of attorney in favor of Hidalgo as his agent and that he should represent him and administer various properties he owned and possessed in Manila. After Hidalgo occupied the position of agent and administrator of De la Pena y Gomiz’s property for several years, the former wrote to the latter requesting him to designate a person who might substitute him in his said position in the event of his being obliged to absent himself from these Islannds From the procedure followed by the agent, Hidalgo, it is logically inferred that he had definitely renounced his agency and that the agency was duly terminated according to the provisions of art 1782 Although the word “Renounce” was not employed in connection with the agency executed in his favor, yet when the agent informs his principal that for reasons of health and by medical advice he is about to depart from the place where he is exercising his trust and where the property subject to his administration is situated, abandons the property, turns it over to a third party, and transmits to his principal a general statement which summarizes and embraces all the balances of his accounts since he began to exercise his agency to the date when he ceased to hold his trust, it then reasonable and just to conclude that the said agent expressly and definitely renounced his agency. Ker & Co. v. Lingad Issue: ACCEPTANCE OF CHECKS INDORSED BY AN AGENT; RULING IN THE CASE OF INSULAR DRUG CO. v. NATIONAL. Held:— In Insular Drug Co. v. National, 58 Phil. 685 (1933), the Court made the pronouncement that." . .The right of an agent to indorse commercial paper is a very responsible power and will not be lightly inferred. A salesman with authority to collect money belonging to his principal does not have the implied authority to indorse checks received in payment. Any person taking checks made payable to a corporation which can act by agents, does so at his peril, and must abide by the consequences if the agent who endorses the same is without authority. 6 Ker & Co. v. Lingad Issue: W/N the relationship thus created is one of vendor and vendee (contract of sale) or of broker and principal (contract of agency) Held: Broker and principal- contract of agency. By taking the contractual stipulations as a whole and not just the disclaimer, it would seem that the contract between them is a contract of agency The CTA, in considering such stipulations provided in the contract, concluded that all these circumstances are irreconcilably antagonistic to the idea of an independent merchant :CTA: upon analysis of the whole, together with actual conduct of the parties thereto, that the relationship between them is one of brokerage or agency National Internal Revenue Code: defined Commercial broker as all persons, other than importer, manufacturers, producers or bona fide employees who, for compensation or profit, sell or bring about sales or purchase of merchandise for other persons or bring proposed buyers and sellers together and also includes commission merchants such as Ker in this case *The mere disclaimer in a contract that an entity like Ker is not “the agent or legal representative for any purpose whatsoever” does not suffice to yield the conclusion that it is an independent merchant if the control over the goods for resale of goods consigned is pervasive in character *thus, SC rejected Ker’s petition to reverse decision of CTA. Ker & Co. v. Lingad Issue: W/N the relationship thus created is one of vendor and vendee (contract of sale) or of broker and principal (contract of agency) 7 Held: 8 Column Heading Column Heading Row Heading Text 123.45 Row Heading Text 123.45