Official Development Assistance Provided by European Union Institutions in Support of Agriculture and Related Policy Objectives - Research Report

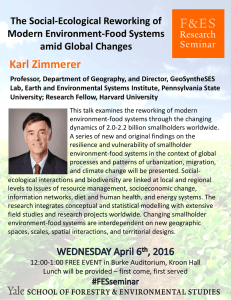

advertisement