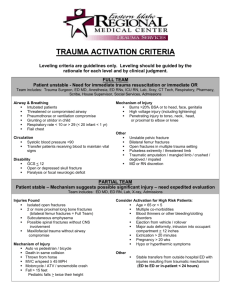

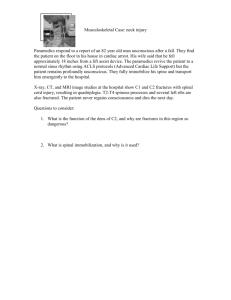

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/41850069 Early history of operative treatment of fractures Article in Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery · March 2010 DOI: 10.1007/s00402-010-1082-7 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 18 1,193 1 author: Jan Bartonícek Military University Hospital Prague 165 PUBLICATIONS 994 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Posterior malleolus fractures, Scapular fractures View project All content following this page was uploaded by Jan Bartonícek on 20 August 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 DOI 10.1007/s00402-010-1082-7 TRAUMA SURGERY Early history of operative treatment of fractures Jan Bartoníbek Received: 29 December 2009 / Published online: 9 March 2010 © Springer-Verlag 2010 Abstract Surgery in the Wrst half of the nineteenth century was primarily dominated by pain and fear of lethal infections. Therefore, the absolute majority of fractures and dislocations were treated non-operatively. Development of operative treatment of fractures was inXuenced by three major inventions: anaesthesia (1846), antisepsis (1865) and X-rays (1895). The Wrst to use external Wxation is traditionally considered to be Malgaigne (1843). However, his devices cannot be considered as external Wxation. Von der Höhe, in 1843, Wxed a non-union of the femur by inserting into both fragments a couple of screws transversely connected outside the wound. Von Langenbeck in 1855 treated a non-union of the humerus with screws connected by a devise designed for this purpose. A predecessor of nailing of acute diaphyseal fractures may be considered to be Wxation of diaphyseal non-unions of the femur, humerus and tibia with ivory intramedullary pegs, performed by DieVenbach in 1846. Nevertheless, until 1885, osteosynthesis was still a Cinderella having at its disposal mainly wires, ivory pegs and very primitive types of external Wxation. During the following 35 years (1886–1921), operative treatment of fractures witnessed an unprecedented revolution. Radiology became an integral part of bone and joint surgery. All types of osteosynthesis, i.e. plates (Hansmann 1886), external Wxation (Parkhill 1897) and intramedullary nails (Schöne 1913) were introduced into clinical practice. Basic experiments were undertaken, surgical approaches described and the Wrst textbooks on osteosynthesis published. J. Bartoníbek (&) Department of Surgery, 1st Faculty of Medicine of Charles University and Thomayer University Hospital, Videnska 800, 140 59 Prague 4, Czech Republic e-mail: bartonicek.jan@seznam.cz Keywords History of osteosynthesis · Plates · External Wxation · Intramedullary nails · Surgical approaches Introduction The history of the operative treatment of fractures is a fascinating story that has engaged many authors [3–7, 14–18, 22, 27, 29, 37, 40, 73, 80–82, 87, 88, 103, 104]. The recent 50th anniversary of the foundation of AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesenfrage) was the occasion for its recapitulation. To understand the development of osteosynthesis, it is important not only to become acquainted with the chronological sequence of individual facts, but also to analyze the causes, implications and consequences of individual events, based on original sources. Operative treatment of fractures in the Wrst half of the nineteenth century In the Wrst half of the nineteenth century, the foundations were laid for the modern treatment of injuries of bones and joints, mainly thanks to the textbooks by Pierre-Joseph Desault (1738–1795), Sir Astley Paton Cooper (1768– 1841) and Joseph François Malgaigne (1806–1865), published and translated both in Europe and North America [19, 20, 23, 24, 66–69]. However, but for a few exceptions, fractures and dislocations were treated non-operatively and discussions concentrated primarily on the position of the limb during reduction, the manner of its performance and immobilization of the injured limb. The main obstacles to the development of operative treatment were the pain associated with surgery and, particularly, concern about infection 123 1386 and its potentially fatal consequences. As a result, the most frequent operation at that time was limb amputation, mainly for war injuries and open fractures, with few cases of surgically treated non-unions or acute fractures [6, 10, 24, 25, 29, 33, 36, 93]. The absence of anaesthesia and asepsis were compensated for by the speed and skill of surgeons. The Wrst textbook to deal with osteosynthesis “Traité de l’immobilisation directe des fragments osseux dans les fractures” was published in 1870 [10]. Its author, Laurent Jean Baptiste Bérenger-Féraud (1832–1900), the French chief naval physician and admiral of the French Navy, summarized from literature more than 400 cases of fractures that were operated on. At that time, the problem of anaesthesia had already been solved and the Wrst steps were taken in the prevention of intraoperative infection. BérengerFéraud described, in total, six types of direct Wxation of bone fragments, the most progressive of which were wire cerclage and the Wrst prototypes of external Wxation known at that time. However, in general, operative treatment of fractures was at that time still in its infancy. Discovery of anaesthesia, antisepsis and X-rays (1846–1895) Surgery in the Wrst half of the nineteenth century was primarily dominated by pain and fear of lethal infections. Surgeons were, to a great extent, inXuenced by their “blindness” resulting from the absence of a method that would allow an accurate diagnosis of fractures and dislocations, or monitoring the course of healing, outcomes and complications of the treatment. All this changed radically within 50 years. On 16 October 1846, William Thomas Green Morton (1819–1868), an American dental surgeon, described for the Wrst time the administration of inhaled ether vapour as an anaesthetic during operation. In the space of a few months, this method had also spread to Europe. The British surgeon Joseph Lister (1827–1912), who lived and worked in Edinburgh and later moved to London, was inXuenced by Pasteur’s teaching and addressed the prevention of surgical infection [14]. In 1865, he treated successfully an open femoral fracture in an 11-year-old boy using an antiseptic carbolic acid spray. In 1877, he performed osteosynthesis of a closed fracture of the patella, under carbolic acid spray, using a silver wire [65]. This operation became an important part of the history of surgery. In Germany, the Listerian method was actively propagated by Richard von Volkmann (1830–1889) from Halle as early as in 1872 and its use quickly spread all over Germany [37, 102]. In 1886, Ernst Gustav Benjamin von Bergmann (1836–1907) from Berlin introduced asepsis (steam sterilization). Prevention of infection improved also 123 Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 thanks to the introduction of rubber surgical gloves in the 1890s by William Stewart Halsted (1852–1922) in the USA and subsequently by Emil Theodor Kocher (1841–1917) in Europe. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845–1923) made his discovery of X-ray imaging on 8 November 1895 and published it in the Wrst week of January 1896. The Wrst clinical radiograph, showing a projectile in the wrist of a 12-year-old boy, was published in Lancet as early as 22 February 1896!!! One of the Wrst radiographs appeared for instance in the “Atlas of Fractures”, published in 1897 by Heinrich Helferich (1851–1945) from Greifswald [42]. The Wrst book on fractures, which had been diagnosed and treated on the basis of radiographic examination, was published by Carl Beck (1856–1911), an American surgeon of German origin, working in New York, in 1900 [8]. The decisive era of 35 years (1886–1921) In 1885, osteosynthesis was still a Cinderella having at its disposal mainly wires, ivory pegs and very primitive types of external Wxation. After World War I, the situation changed radically. During 35 years (1886–1921), operative treatment of fractures witnessed an unprecedented revolution. Radiology had become an integral part of the bone and joint surgery. Introduced into the clinical practice were all types of osteosynthesis, i.e. plates, external Wxation and intramedullary nails. Basic experiments were undertaken, surgical approaches described and the Wrst textbooks on osteosynthesis published. This extremely fruitful period was split by Roentgen’s invention into two diVerent parts: the pre-radiological and radiological eras. Pre-radiological period (1886–1895) Due to the “blindness” of surgeons, operative treatment Wrst focused on “subcutaneous” fractures, i.e. fractures more easily diagnosed by sight and palpation (patella, olecranon, tibia, clavicle and mandible), as well as fractures resisting non-operative treatment (proximal femur, diaphyseal fractures of the forearm). In spite of this “blindness”, several signiWcant publications appeared in this period. Carl Hansmann (1853–1917), a German surgeon from Hamburg, was the Wrst to publish in 1886 Wxation of fractures by a plate (Fig. 1) [38]. Heinrich Bircher (1850–1923), a Swiss surgeon from Bern, published in 1887 an extensive article on intramedullary osteosynthesis of diaphyseal fractures of the femur and tibia by means of pegs, and of the metaphyseal fractures of the tibia by ivory clamps (Fig. 2) [12]. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 Fig. 1 Hansmanns’ plate (Verh Dtsch Ges Chir 15:134–137, 1886) 1387 Nicholas Senn (1844–1908), an American surgeon from Chicago, dealt in detail in 1893 with the then known methods of osteosynthesis [92]. He studied “absorption of aseptic ivory and bone in the living tissues” and developed a “hollow perforated intra-osseous splint” of which he assumed “absorption in a comparatively short time”. For oblique diaphyseal fractures, he designed an extramedullary “bone ferrule”. He successfully used this absorbable osseous sleeve, made from ox bone, in three patients with non-unions of the femoral, humeral and tibial shafts (Fig. 3). Thus, Senn can be called the father of biodegradable implants. His ferrule was predecessor of the PuttiParham bands. Pietro Loreta (1831–1889), an Italian surgeon and personal physician of Garibaldi, was probably the Wrst in the world to perform, in 1888, an open osteosynthesis of a nonunion of the femoral neck, using multiple cerclage [1]. Julius Dolinger (1849–1937), a Hungarian surgeon from Budapest, Wxed an acute extracapsular fracture of the femoral neck by open osteosuture using silver wire, in 1891 [26]. Fig. 2 Bircher’s intramedullary ivory peg and clamp (Langebeck’s Archiv 34:410– 422, 1887) Fig. 3 Senn’s “hollow perforated intra-osseous splint” (a) and an extramedullary “bone ferrule” (b, c) (Ann Surg 18:125–151, 1893) 123 1388 Willy Meyer (1858–1932), an outstanding American surgeon of German origin and Trendelenburg’s pupil, was the Wrst to treat in the USA a non-union of the femoral neck with two nails in 1892 [71]. Elie Lambotte (1856–1912), a Belgian surgeon and brother of Albin Lambotte, was probably the Wrst to treat an oblique fracture of the tibial shaft with screws, in 1890 [55]. William Arbuthnot Lane (1856–1943), a British surgeon from London, advocated in articles published in 1893–1895 operative treatment of fractures “of such a bone as the patella, tibia, Wbula, clavicle, jaw and olecranon”. He Wxed fractures by wire sutures and later by screws [57–59]. Radiological period (1896–1921) The discovery of X-ray imaging provided bone surgeons with a tool for diagnosing fractures and dislocations, as well as for monitoring fracture healing, evaluation of the Wnal outcome and of any complications. Frederic Jay Cotton (1869–1938) from Boston, the author of an outstanding textbook, wrote in 1910 [21]: “We are fortunate today not only in having the X-ray as an accessory method of diagnosis, but in having, as a result of this diagnostic method and of a vast array of observations made directly at operation, a material for deductions not accessible to previous generations. Wisdom did not begin with this generation, but we have had an unusual opportunity to learn”. Similarly, in 1912 Emil H. Beckman stated: “The use of the X-ray Wrst showed us how very inferior our bone repair work has been” [9]. The development of osteosynthesis was gaining momentum and the number of published articles on this subject was growing, both in Europe and in the USA [9, 13, 28, 31, 32, 34, 35, 39, 49–52, 64, 70, 72, 76–79, 83–85, 89, 94, 95, 97, 98, 100]. Some authors, such as Nienhansen Preston, Schöne and Sherman, became famous in this Weld, on the basis of only one or two publications [76, 83, 84, 89, 95, 96]. Others such as Lane, Lambotte and Hey Groves dealt systematically with operative treatment of fractures and published their work in a book form [44, 46, 55, 56, 60, 63]. This period was symbolically rounded oV with the second edition of Hey Groves’ book in 1921 [46]. The development of implants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries One of the Wrst problems brought about by the introduction of operative treatment of fractures was a total lack of suitable implants and instruments. Therefore, those who wanted to treat fractures operatively tended to develop their 123 Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 own implants. It was a period of testing of suitable materials and the search for adequate surgical approaches. Materials EVorts were concentrated on Wnding a suitable implant material. The oldest implants for internal Wxation of fractures were made from various materials, mainly ivory, bone and metal (bronze, lead, gold, copper, silver, brass, steel, aluminium). Ivory and bone pegs were used for intramedullary Wxation [2, 11, 25]. Silver was used for cerclage wires, plates and intramedullary pins. However, the Wrst plates were made from nickel-coated sheet steel [38], and later from silver [98], high carbon steel [60, 63], vanadium steel [95], aluminium [55, 56] or brass [13]. Nevertheless, all the metals were highly problematic from the viewpoint of their mechanical properties and corrosion. This problem was solved by the use of stainless steel. Although it was invented before WWI, it was not used for the production of implants until much later [101]. Experiments Many authors tested their ideas experimentally. One of the Wrst was Ferdinand Riedinger (1844–1918), a German surgeon from Würzburg. His article of 1881, dealing with nonunions of the forearm, included a number of experiments on rabbits and dogs [86]. While the implanted intramedullary ivory pegs and bone blocks integrated into the bone without problem, the wooden and rubber implants caused infections. The article was supplemented also with microscopic drawings not only of integrated ivory pegs, but also of the adjacent physis (Fig. 4). An outstanding researcher was Nicholas Senn, who in 1889 published a book on experimental surgery [91]. He not only studied the healing of intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck [90], but veriWed in dogs “the feasibility, safety and utility of direct fracture Wxation with bone ferrules” [92]. Harry M. Sherman (1854–1921), an American surgeon from San Francisco, studied experimentally in 1914 several signiWcant issues, including: “Are screws and plates tolerated inside a joint?” and “What are the early and late eVects of well, and insuYciently, countersunk screws”. Among other things, he found out that “The use of two diVerent metals in these screws and plates does not change the results in the articulation, except so far as the possible electrical reaction is concerned in the staining of the tissues” [94]. The most extensive and comprehensive experiments were made from 1914 by Hey Groves [44]. In most of his 100 experiments, he studied on the cat tibias and femurs the healing of fractures Wxed by plates, intramedullary pegs Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 1389 Fig. 4 Riedinger’s experiments: a ivory peg (a) incorporated in medullary channel, b physis of operated on bone, c physis of control contralateral bone, the diVerence in the height of both physes is clearly visible (Arch Klin Chir 26:985–993, 1881) (ivory, steel, metallic magnesium, wire spirals, bone, decalciWed bone) and external Wxators. He also studied Wlling of bone defects with bone pieces or chips and regeneration of bone after subperiosteal removal of a piece of its entire thickness. The results of his experiments were illustrated by “skiagrams”, and photographs of microscopic specimens and microscopic sections. His conclusions are valid to this day. He thereby anticipated much of the experimental work of AO by more than 40 years. Cerclage Wire cerclage was one of the earliest methods of internal Wxation [1, 10, 26, 29, 65, 71, 81, 82]. Improvement of this technique was published almost simultaneously by three authors. Robert Milne, an American surgeon, described in 1912 cerclage using Xexible threaded pins [72]; Vittorio Putti (1880–1940), an Italian orthopaedic surgeon, presented in 1914 cerclage with a narrow metal band [85]. Two years later (1916), a similar method was published by Frederick William Parham (1856–1927), an American surgeon from New Orleans [77]. The implant spread worldwide under the name Putti-Parham bands and in various modiWcations it is occasionally used today. Plates The Wrst to publish his experience with plate osteosynthesis was Carl Hansmann, in 1886, as mentioned above [39]. Hansmann used plates from nickel-coated sheet steel in 20 cases, 15 times in fractures (8 fractures of the tibia, 3 fractures of the femur, 1 fracture of the radius, 1 olecranon fracture and 2 fractures of the mandible) and 5 times in non-unions (humerus, ulna, radius, femur, tibia). Part of the plate, and the shanks of the screws that Wxed it to the bone, protruded from the wound and could be therefore removed percutaneously. Hansmann kept the surgical wound strictly aseptic and used washable external rubber splints. He did not mention any complications and removed the plates after 4–8 weeks. Neither in Germany nor elsewhere in Europe did Hansmann have a successor for a long time. It was only after a 14-year interval that other publications in this Weld appeared, mainly in the USA. Lewis W. Steinbach (1851–1913) from Philadelphia in 1900 treated four cases of fracture of the tibia with a silver plate of his own design, Wxed to each of the fragments by two steel screws [98]. He also described in detail the operative technique, including the use of drainage tubes. It was the Wrst publication to use radiography to document the injury, the plate Wxation and the Wnal outcome after implant removal. Edward Martin (1859–1938), also from Philadelphia, published in 1906 radiographs of fractures of the femoral shaft, and the tibial shaft and metaphysis, treated with plates and monocortical screws [70]. Among radiographs published by Martin was also a healed fracture of the distal shaft of the radius treated with plate and bicortical screws by John Ashhurst (1839–1900) 7 years before publication of Martin’s article, i.e. in 1899! William Lawrence Estes (1855–1940), from South Bethlehem, in 1912 in an article on fractures of the femoral shaft, discussed in detail the operative technique, stating: “In 1886 the writer devised a plate for direct Wxation of fractured bones. It has been used in his clinic with good results ever since. It is a modiWcation of the early Schede plate. It is made of soft steel, nickel plated. It has been known to bend a little but has never broken while in use” [28]. This indicates that Estes developed the plate simultaneously with Hansmann! Unfortunately, no details could be traced. Joseph Augustus Blake (1864–1937) of New York reported 106 surgically treated fractures in 1912 dealing in detail with plate osteosynthesis [13]. From 1905, he used plates of his own design, made mostly of silver, and also occasionally of brass or steel. He later applied the Lane plates to the treatment of fractures of the shafts of the humerus, ulna, radius and femur. Emil H. Beckman (1872–1916) from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester was probably the Wrst to publish, in 1912, a radiograph of a fracture of the medial malleolus Wxed with a plate [9]. William O’Neil Sherman (1880–1979) from Pittsburgh was a strong proponent of internal Wxation in the USA and contributed to signiWcant improvements in plate design. As he worked for Carnegie Steel Company, he had optimal conditions for experimenting with both the material and 123 1390 design of plates. He published his results in 1912 [95]. His sophisticated plates, designed on the basis of mechanical principles, were made of vanadium steel, using self-tapping monocortical screws. Later, in 1926, he dealt in detail with plate osteosynthesis of diaphyseal fractures of the femur, attaching the plates with bicortical screws [96]. In 1914, Miller Edwin Preston (1879–1928) from Denver designed the Wrst angled blade plate for osteosynthesis of femoral neck fractures, although he used it probably only in a few cases [83]. At the beginning of the twentieth century, plate osteosynthesis started spreading in Europe, mainly due to William Arbuthnot Lane and Albin Lambotte, who were followed several years later by Ernest William Hey Groves. Albin Lambotte stated in the 1907 Wrst edition of his book that from 1900 he had treated various diaphyseal fractures with plates made of aluminium, which he Wxed by self-tapping monocortical screws [55]. In the second edition of his book, published in 1913, he described three diVerent types of plates, one of which was contoured [56]. Albin Lambotte also used plates for the Wxation of fractures of the distal humerus, distal femur, proximal tibia and the mandible. William Arbuthnot Lane published, in 1907, a successful Wxation of diaphyseal fracture of the femur using a pair of plates [61]. The second edition of his book in 1914 was devoted primarily to plate osteosynthesis [63]. Lane Wxed carbon steel plates of his own design with monocortical screws. Their disadvantage was their Ximsiness and the necessity to immobilize postoperatively the limbs with external splints. Lane used plates for the Wxation of all diaphyseal fractures of the clavicle, humerus, radius, ulna, femur, tibia and Wbula, and also of both malleoli, olecranon and scapula. Henry S. Souttar (1875–1964), an outstanding surgeon from London, who later became famous for his operation for mitral stenosis, published in 1913 his own design of a plate Wxed with a Wnely threaded screw [97]. He considered the vascular impact of the plate on the bone and tried to reduce its “footprint” on the bone in order to not impair healing. Ernest William Hey Groves dealt in detail with plate osteosynthesis, including experiments on animals [44]. For instance, he designed curved plates or plates with T-shaped ends. He compared the mechanical properties of the Lane and Lambotte plates, as well as Wxation properties of “wood” and “metal” screws. Hey Groves also used interfragmentary Wxation and bolted plates. Due to the eVorts of the above-mentioned authors, plates became, at the beginning of twentieth century, the most frequently used implants for internal Wxation of fractures. External Wxation The Wrst to use external Wxation is traditionally considered Malgaigne (Fig. 5) [16, 81, 82]. In 1840, Malgaigne used 123 Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 Fig. 5 Malgaigne’s “external Wxators”: a pointe métallique, b griVe métallique (Traité des fractures et des luxations. JB Baillière, Paris 1847) and in 1843 published pointe métallique, by which he percutaneously Wxed fractures [66]. However, this device cannot be considered as external Wxation [18]. The same applies to griVe métallique, which Malgaigne designed in 1843 and described in 1847 [66]. GriVe métallique was subsequently modiWed by Rigaud in 1850 and Chassin in 1852 [10]. It was not a typical external Wxator and was intended only for fractures of the patella [10, 18, 66]. Povacz [82] in “Historie der Unfallchirurgie” ascribed the Wrst application of external Wxation to Carl Wilhelm Wutzer (1789–1863) from Bonn, Germany. In 1843, Wutzer allegedly used the Wrst external Wxator to treat a nonunion of femur persisting for 11 years [82]. But the reality is diVerent. Geller [33] in his dissertation thesis in 1847 brieXy mentioned that C. Claus von der Höhe Wxed in 1843 at Wutzer’s clinic a non-union of the femur by inserting into both fragments a couple of screws transversely connected outside the wound. However, the patient died. Therefore, Wutzer in 1846 treated a non-union of the femur by resection of the ends of the fragments and use of a goldwire cerclage, and the operation was successful [33]. Bernhard Rudolf Konrad von Langenbeck (1810–1887) from Berlin in 1855 treated a non-union of the humerus with screws connected by a devise designed for this purpose [30]. Due to infection, the Wxator had to be removed after 12 days and the non-union was left to heal conservatively. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 1391 Fig. 7 Parkhill’s external Wxator (Ann Surg 28:552–570, 1898) Fig. 6 Heine’s external Wxators: Fig. 1 and 2 “ivory pins” Wxator, Fig. 3 and 4 “pin-less” external Wxator. (Langebeck’s Archiv 22:472– 495, 1878) An original and today quite unknown concept of external Wxation was developed by Carl Wilhelm v. Heine (1839– 1877), who worked in Innsbruck and later in Prague [41]. In 1872, Heine Wxed a non-union of the femur by two ivory pins inserted transversely through both cortices of each fragment, threaded at the end to accommodate the end cap. Each of the pins was transversely connected to the bar. The other end of the bar was Wxed in an arch, the arms of which were integrated into the plaster bandage (Fig. 6). However, this Wxation proved to be inadequate. Therefore, in the patients with non-union of the humerus, tibia and femur, the fragments were directly Wxed by bone clamp jaws resembling a pin-less external Wxator. The clamp protruded from the surgical wound and was connected by a transverse bar Wxed again in the plaster bandage (Fig. 6). In this way, Heine healed only the non-union of the humerus, while the other cases required amputation. External Wxation, as we know it today, started to develop as late as at the turn of the twentieth century. In the USA, in 1897–1898 Clayton Parkhill (1860–1902) from Denver designed external Wxation clamps and used them for diVerent types of fractures (Fig. 7) [78, 79]. His early death, caused by acute appendicitis when he refused operation, prevented him from developing this method, which was then further developed by his colleague Leonard Freeman (1860–1935). In 1911, Freeman described the detailed operative technique, including various tips and tricks [31]. In 1919, he introduced the “turnbuckle” to facilitate reduction, which was a highly sophisticated precursor of the AO femoral distractor [32]. Howard Lilienthal (1861–1946), from New York, who later became an outstanding thoracic surgeon, used external Wxation of his own design in diaphyseal fractures, including the infected ones in 1912 [64]. In Europe, Albin Lambotte became the father of external Wxation. He developed his own external Wxator clamps, independently of Parkhill. The design of the Lambotte Wxator was highly sophisticated and was very similar to the current AO tubular Wxator. The screws were self-threading and self-tapping and the clamps provided the Wxator with diVerent degrees of freedom. Lambotte used it successfully from 1902 for all diaphyseal fractures [55, 56]. In 1916, Ernest Hey Groves described diVerent types of external Wxator clamps for intraoperative reduction of fractures, allowing both distraction and compression of fragments. For stabilization of diaphyseal fractures of the femur and tibia, he used external Wxator frames [44]. Although external Wxation was not used as frequently as plates, it was relatively widespread both in Europe and the USA during the study period. Intramedullary nailing A predecessor of nailing of acute diaphyseal fractures may be considered to be Wxation of diaphyseal non-unions of the femur, humerus and tibia with ivory intramedullary pegs, performed by the prominent Berlin surgeon Johann Friedrich DieVenbach (1792–1847) and published in 1846 [25]. The same method for a non-union of tibia was used in 1861 by the German surgeon Theodor Bilroth (1829–1894), 123 1392 who worked at that time in Zurich [11]. He removed the ivory grafts 2 weeks after operation, examined them microscopically and found their partial resorption. His method consisted in opening the medullary cavity of both diaphyseal fragments with a drill. The ivory grafts inserted subsequently served as biological stimulators, rather than as mechanical Wxation. Antisepsis was not known at that time and thus the wound always became infected and the pegs had to be removed after 1–3 weeks. However, the subsequent inXammatory hyperaemia often resulted in healing of the non-union. The superWcial resorption of ivory pegs by macrofags was described also by Emanuel Aufrecht (1844–1933), from Magdeburg. In 1877, Aufrecht microscopically examined ivory pegs, which an outstanding German surgeon Werner August Hagedorn (1831–1894), had used to Wx a non-union of the tibia under antiseptic conditions [2]. Carl Wilhem v. Heine described in 1878, in an article published after his death [41], a successful Wxation of diaphyseal non-union of humerus and ulna with ivory pegs. Ferdinand Riedinger studied experimentally internal Wxation with ivory pegs in 1881 [86]. Heinrich Bircher treated successfully in 1887 diaphyseal fractures of the femur and tibia with intramedullary pegs [12]. A similar type of intramedullary Wxation was the intraosseous splint described by Nicolas Senn in 1893 [92]. Metallic nails were initially used to Wx fractures of the articular ends of bones, particularly in fractures of the femoral neck [71, 74, 93]. The Wrst operation in this respect was performed by Langenbeck in 1858 [93]. Paul Niehans (1848–1912) from Bern, in 1904, described treatment of a supracondylar humeral fracture in a child [76]. The author performed open reduction and nailing in six cases, from the Kocher radial approach after temporary osteotomy of the olecranon! The Wrst successful “closed” nailing of a diaphyseal fracture was described by Georg Schöne (1875–1960) working in Greifswald in 1913 [89]. Under Xuoroscopic control, he treated a total of seven diaphyseal fractures of the ulna or radius, using percutaneously inserted silver pins (Fig. 8). A highly signiWcant, although until now not fully recognized, contribution to intramedullary nailing was made by Ernest William Hey Groves. He conducted a series of experiments with intramedullary pegs and nails made of bone, ivory and metal [44, 46]. Hey Groves also tested diVerent designs of nails. In 1918, he treated two cases of gunshot fracture of the femoral shaft by a steel nail [45]. Unfortunately, Hey Groves’ remarkable contribution to intramedullary osteosynthesis has been rather overshadowed by the eminence accorded to Gerhard Küntscher. Despite all eVorts, nails did not win recognition in the treatment of diaphyseal fractures at the beginning of the 123 Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 Fig. 8 Schöne’s intramedullary nailing of forearm fractures (Münch Med Wschr 60:2327–2328, 1913) twentieth century. One of the main obstacles was the lack of a suitable material. Surgical approaches It is surprising that the authors of this period paid such little attention to operative approaches in their books and articles. The Wrst book containing a more detailed description and Wgures showing operative approaches was Operationslehre (Textbook of Operative Surgery) published in 1907 by Theodor Kocher, a Swiss surgeon from Bern [50]. Kocher described therein a number of approaches that today bear his name (hip, elbow and calcaneus). The very Wrst publication dealing in detail with operative approaches to long bones was the 1918 article by James Edwin Thompson (1863–1927) [99]. This English surgeon and anatomist, who moved to Galveston in Texas [17], deWned the requirements for operative approaches that are valid till today: • • • • ease of access, preservation of all nerves, both sensory and motor, prevention of unnecessary injury to muscles, preservation of the vascular supply. Subsequently, he described a number of approaches to all the long bones, including their articular ends. Of the whole article, history remembers merely the posterolateral approach to the radial shaft that is today named after him. It was not until 1945 that the Wrst two comprehensive textbooks of operative approaches were published. The Wrst of them was “Extensile exposure applied to limb surgery” written by Arnold Kirkpatrick Henry (1886–1982) [43]. This Irish surgeon and anatomist, an outstanding representative of the Dublin surgical school, formulated the concept of extensile approaches in internervous planes. In addition to general principles, he described also a number of approaches, the best known of which is Henry’s volar approach to the radius. A comprehensive “Atlas of surgical Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 approaches to bones and joints” containing also approaches to the spine, pelvis, mandible and temporomandibular joint was published by TouWck Nicola (1894–1987), an American orthopaedic surgeon from New York [75]. Luminaries of bone surgery of the Wrst half of the twentieth century Outstanding from the above-mentioned authors, who more or less contributed to the development of osteosynthesis, are three extraordinary personalities especially worthy of mention. William Arbuthnot Lane (1856–1943), the British surgeon working in London, was a pioneer of internal Wxation who treated closed fractures operatively from 1892. His Wrst publications may be considered as the Wrst declaration rationally defending operative treatment of fractures [57–59]. In 1905, he published the book “The operative treatment of fractures” [60]. In 1907, he added also plates of his own design [61]. These plates appeared as a preferred method only in the second edition of his book in 1914 [62]. Lane was an excellent surgeon with a profound knowledge of anatomy. He was the originator and a strong proponent of the “no touch” technique, for which he developed a number of dedicated instruments [15, 70, 78]. As a result, he had a very low incidence of infective complications. He was in close contact with the German Surgical Society, and regularly attended its congresses at the beginning of the twentieth century. His concepts became very popular, particularly in the USA [39, 62]. Albin Lambotte (1866–1955), a Belgian surgeon from Antwerp, was a true genius of bone surgery, who at the beginning of the twentieth century extraordinarily inXuenced its development [27, 73, 81]. His contribution is remarkable mainly due to the comprehensiveness of the methods he used. Plates, external Wxation, cerclage, screws and nails, all of which he used for various types of fractures. In addition, he invented or improved a number of instruments. In 1907, he published the book “L’intervention opératoire dans les fractures récentes et anciennes envisageé particuliérement au point de vue de l’ostéo-synthèse” [55] the title of which presents for the Wrst time the term “osteosynthesis”. The revised edition of 1913 is a work, which to date remains fascinating by virtue of its scope of coverage [56]. Unfortunately, it has been translated into neither English nor German. Both editions contain a detailed documentation of a great number of his surgical cases. Lambotte used radiographs as a standard for diagnosis, as well as for monitoring the course of healing. He carefully recorded the radiograph documentation of each of his patients in the form of sche- 1393 matic drawings made from X-rays using a pantograph, sometimes including functional results. The technique of his operations and their results were well ahead of his time. Although Lambotte was well known in the English-speaking surgical world, due to the language barrier his ideas could not spread as did those of Lane. Ernest William Hey Groves (1872–1944) from Bristol is nowadays unjustly neglected in the history of osteosynthesis. During World War I, in 1916, he published a textbook that is almost unknown today “On modern methods of treating fractures” [44]. A second edition followed in 1921 [46]. The textbook surprises by its comprehensive coverage of the given issue and many of its concepts are almost the same as in current textbooks on bone trauma. The reader will also Wnd here three extensive chapters dealing with operative treatment, showing in detail how the author used plates, nails and external Wxation. His extensive experiments on animals using all these implants are unique. A large space was devoted to mechanical properties of diVerent types of plates and screws suitable for the cortical bone. In fractures of the femur, he introduced nailing from the tip of the greater trochanter, as well as retrograde nailing from the fracture site [45]. In some cases, the author Wxed intramedullary pegs by transversely inserted screws, which anticipated the concept of locking nailing. Hey Groves was a universal bone surgeon. He studied also the application of solid bone grafts and used them to treat fractures of the femoral neck [48]. He signiWcantly inXuenced reconstructive surgery of the hip and, in 1927, designed an ivory hip replacement, similar in form to the later Judet prosthesis [47]. In spite of this, Hey Groves’ historical contribution to operative treatment of fractures has not yet been fully appreciated. Contribution of individual surgical schools British surgical school Throughout the nineteenth century and in the early twentieth century, British surgeons were pioneers in the Weld of closed and operative treatment of fractures. Lister, Lane and Hey Groves could rely on the foundations laid by Sir Astley Cooper, and the Dublin and Edinburgh surgical schools [4–6, 19]. Lister succeeded in reducing infection [14]. Lane became a respected proponent of osteosynthesis and the “no touch technique”, not only in Great Britain, but also in Germany and the USA [15]. Hey Groves studied all types of osteosynthesis, including experimental ones; he published the Wrst modern textbook on closed and operative treatment of fractures and contributed also to the development of reconstructive hip surgery [44–48]. 123 1394 German surgical school In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Germanspeaking surgeons became strong advocates of the operative treatment of fractures and promptly accepted the Listerian principles as early as in 1872 [14, 37]. In addition, many of them gained experience from the Prussian–Austrian (1866) and German–French (1870) wars. As a result, in the 70s and 90s of the nineteenth century, German surgery had the edge over the rest of the world. In 1847–1913, German surgeons published key original articles on external Wxation, plate osteosynthesis and intramedullary nailing [25, 30, 33, 38, 41]. Unfortunately, none of these German authors dealt systematically with operative treatment of fractures. This was the main cause for the gradual decline of German bone surgery from its position of pre-eminence at the beginning of the twentieth century. The only signiWcant proponent of operative treatment in Germany in the Wrst decades of the twentieth century was Fritz König (1866–1952), the son of the well-known German surgeon, Franz König (1832–1910) [51–54, 104]. Fritz König was also the author of the Wrst German book on osteosynthesis, published as late as in 1931 [54]. French surgical school In the Wrst half of the nineteenth century, the French school of bone surgery, represented by Dupuytren, Larrey and mainly Malgaigne, reached its climax. However, BérangerFéraud’s book of 1870, dealing with osteosynthesis, was an epilogue of this era [10]. Its author had no successor in France for many years. The situation radically changed with Albin Lambotte, a Belgian surgeon with links to French surgery and writing in French, whose contribution was cardinal [55, 56]. American surgical school At the beginning of the nineteenth century, surgeons in the USA had established close contacts with the English, German and French surgical communities. Clayton Parkhill signiWcantly inXuenced the development of external Wxation, both in the USA and around the world. Also, the development of plate osteosynthesis was extraordinary in the USA, from the very beginning of the introduction of this method. It is amazing how many interesting articles dealing with operative treatment of fractures, published by a signiWcant number of authors, appeared in the Wrst few years of the twentieth century [9, 13, 28, 34, 49, 64, 83, 94, 95, 100]. Writers discussed in detail operative techniques and many other related topics. Most of the articles were amply documented by radiographs and drawings. This period culminated around 1912. Sherman plates subse- 123 Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 quently spread all over the world. Many of the above-mentioned authors excelled also in other surgical disciplines (thoracic surgery, neurosurgery, andrology), but in fact none of them was a “full-time” specialist in bone and joint surgery. This was probably one of the reasons why a textbook on internal Wxation of fractures did not appear in the USA until as late as 1947 [101]. Epilogue It is fascinating how aptly Preston deWned the main problems of internal Wxation of fractures as early as in 1916 [84]: “There is no branch of surgery in which nature is more exacting then bone work. To be successful in this Weld, the cases must be carefully selected, the most rigid asepsis should be observed, the surgeon must possess a good working knowledge of anatomy and fully appreciate the laws of stress, strain and leverage. The internal Wxation of a fracture is decidedly an engineering problem, as well as a surgical procedure, and it is probable that a larger percentage of failures have resulted from violation of mechanical laws than have been due to faulty surgical asepsis.” After World War I, the way opened for operative treatment of fractures to spread successfully all over the world. Plate osteosynthesis, particularly, became highly popular both in Europe and in the USA. However, the Wrst generation of advocates of osteosynthesis was no longer as active in publishing works on bone surgery as hitherto. As a result, internal Wxation of fractures, in many cases, passed into the hands of unprepared surgeons, whose knowledge was insuYcient to understand the principles deWned and respected by their predecessors. Over a short period, a large number of catastrophes occurred to swing the pendulum of specialized public opinion in favour of conservative treatment, for many years. This, however, cannot change the fact that in a historically very short period of 50 years (1870–1921), solid foundations were laid for operative treatment of fractures, many of which we continue to respect to this day. Acknowledgments This article could not have appeared without the extraordinary help in collecting original sources, oVered by Ms. Ludmila Frajerová from the Klementinum (Czech National Library) and Ms. Mirka Plecitá from the 3rd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague and Arsen Pankovich, MD. I also wish to thank Ms. Ludmila Bébarová and Chris Colton, MD for editing the English version of the manuscript. References 1. Anonymous (1888) Treatment of ununited fracture of the neck of femur. Brit Med J1443:446 Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 2. Aufrecht E (1877) Ueber Riesenzellen in Elfenbeinstiften, welche zur Heilung einer Pseudoarthrose eingekeilt waren. Centrallblat Med Wissensch 15:465–467 3. Bagby GW (1977) Compression bone-plating. J Bone Joint Surg A 59:625–631 4. Bartoníbek J (2002) History of fractures of the proximal femur. Contribution of the Dublin Surgical School of the Wrst half of 19th century. J Bone Joint Surg B 84:795–797 5. Bartoníbek J (2002) Internal architecture of proximal femur – Adam’s or Adams’ arch? Historical mystery. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 122:551–553 6. Bartoníbek J (2004) Proximal femur fractures—the pioneer era of 1818 to 1925. Clin Orthop Rel Res 419:306–310 7. Bartoníbek J, Cronier P (2010) History of the treatment of scapula fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 130:83–92 8. Beck K (1900) Fractures: with an appendix on the practical use of the Roentgen rays. Saunders, Philadelphia 9. Beckman EH (1912) Repair of fractures with steel splints. Surg Gyn Obst 14:71–76 10. Bérenger-Féraud LJB (1870) Traite de l’immobilisation directe des fragments osseux dans les fractures. Adrien Delahaye, Paris 11. Bilroth Th (1861) Ueber Knochen—resorption. Langebeck’s Archiv (Arch Klin Chir) 2:118–132 12. Bircher H (1887) Eine neue Methode unmittelbarer Retention bei Fracturen der Rohrenknochen. Langebeck⬘s Archiv (Arch Klin Chir) 34:410–422 13. Blake JA (1912) The operative treatment of fractures. Surg Gyn Obst 14:338–345 14. Bonin JG, LeFanu WR (1971) Joseph Lister 1827–1912. A bibliographical biography. J Bone Joint Surg B 49:4–23 15. Brand RA (2009) Sir William Arbuthnot Lane, 1856–1943. Clin Orthop Rel Res 467:1939–1943 16. Broos PLO, Sermon A (2004) From unstable internal Wxation to biological osteosynthesis. A historical overview of operative fracture treatment. Acta Chir Belg 104:396–400 17. Burns OR, Campbell HG (1999) The extraordinary inXuences of two British physicians on medical education and practice in Texas at the turn of the 20th century. Vesalius 5:79–84 18. Colton CL (2009) The history of fracture treatment. In: Browner BD, Jupiter JB, Levine AM, Trafton PG, Ch Kretek (eds) Skeletal trauma. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 3–31 19. Cooper AP (1822) A treatise on dislocations and on fractures of the joints. Longman, Hurst, London 20. Cooper BB (ed) (1851) A treatise on dislocations and on fractures of the joints by Sir Astley Cooper. Blanchard and Lea, Philadelphia 21. Cotton FJ (1910) Dislocation and joint fractures. Philadelphia, Saunders 22. Crawford RR (1973) A history of the treatment of nonunion of fractures in the 19th century, in the United States. J Bone Joints Surg A 55:1685–1697 23. Desault PJ (1798) Oevres chirurgicales, ou tableau de la doctrine et de la pratique dans le traitement des maladies externes par Xav. Bichat. Desault, Méquignon. Devilliers, Deroi, Paris 24. Desault PJ (1805) A treatise on fractures, luxations and other aVections of the bones. In: Bichat X (ed) Fry and Kammerer. Leatitia court, Philadelphia 25. DieVenbach JF (1846) Neue sichere Heilmethode des falschen Gelenkes oder der Pseudoarthrose mittels Durchbohrung der Knochen und Einschlagen von Zappfen. Casper’s Wochenschriftt Gesam Heilk 46–48:727–734, 745–752, 761–765 26. Dollinger J (1891) Schenkelhlasbruch geheilt mit Silberdrahtnaht. Centrallblat Chir 18:456–457 27. Elst VE (1971) Les débuts de l’ostéosynthèse en Belgique. Private publication for Société Belge de Chirurgie Orthopédique et de Traumatologie, Imp des Sciences, Brussels 1395 28. Estes WL (1912) End results of fractures of the shaft of the femur. Ann Surg 56:162–184 29. Evans PEL (1983) Cerclage Wxation of fractured humerus in 1775. Fact or Wction? Clin Orthop Rel Res 174:138–142 30. Fock C (1855) Pseudoarthrosis humeri sinistri mit gleichzeitiger Fract. colli humeri dextri und Querbruch im unteren Drittheil desselben Oberarmes. Volständige Heilung. Deutsche Klinik 314–315 31. Freeman L (1911) The treatment of oblique fractures of the tibia and other bones by means of external clamps inserted through small openings in the skin. Trans Am Surg Assoc 29:70–93 32. Freeman L (1919) The application of extension to overlapping fractures, especially of the tibia, by means of bone screws and turnbuckle, without open operation. Ann Surg 70:231–235 33. Geller FCHJ (1847) De resectione pseudoarthroseos e femoris fractura ortae. Dissertatio inauguralis chirurgica. Lechner, Bonn 34. Gerster JCA (1912) The reduction of fragments in fractures of the long bones. Ann Surg 57:769–779 35. Gerster JCA (1913) A further note on reduction of fragments in fractures of the long bones at open operation. Ann Surg 58:656–658 36. Gurlt E (1860) Handbuch der Lehre von der Knochenbrüchen. Medinger Sohn and Co., Frankfurt 37. Hach W, Hach V (2001) Richard von Volkmann und die Chirurgie and der Friedrichs-Universität in Halle von 1867 bis 1889. Zentralbl Chir 126:822–827 38. Hansmann H (1886) Eine neue Methode der Fixierung der Fragmente bei complicierten Fracturen. Verh Dtsch Ges Chir 15:134– 137 39. Harrigan AH (1919) The use and value of the Lane plate. Ann Surg 69:161–170 40. Heim UFA (2001) The AO phenomenon. Huber, Bern 41. Heine C (1878) Ueber operative Behandlung der Pseudarthrosen. Langebeck⬘s Archiv (Arch Klin Chir) 22:472–495 42. Helferich H (1897) Atlas und Grundriss der traumatischen Frakturen und Luxationen. 3 AuXage. Lehmann, München 43. Henry AK (1945) Extensile exposure applied to limb surgery. Longman, London 44. Hey Groves EW (1916) On modern methods of treating fractures. Wood and Co, New York 45. Hey Groves EW (1918) Ununited fractures with special reference to gunshot injuries and the use of bone grafting. Brit J Surg 6:203–247 46. Hey Groves EW (1921) On modern methods of treating fractures. Wood and Co/Wright, New York/Bristol 47. Hey Groves EW (1926–1927) Some contributions to reconstructive surgery of the hip. Br J Surg 14:486–517 48. Hey Groves EW (1930) Treatment of fractured neck of the femur with especial regard to the results. J Bone Joint Surg 12:1–14 49. Huntington TW (1912) The operative treatment of recent fractures of the femoral shaft. Ann Surg 56:420–431 50. Kocher T (1907) Chirurgische Operationslehre. Fisher, Jena 51. König F (1902) Aussprache zu: Knochennaht. Verh Dtsch Ges Chir 31(I):36–39 52. König F (1905) Ueber die Berichtigung frühzeitiger blutiger EingriVe bei subcutanen Knochenbrüchen. Arch Klin Chir 76:725–777 53. König F (1924) Die operative Behandlung der Knochenbrüche. Arch Klin Chir 133:380–388 54. König F (1931) Operative Chirurgie der Knochenbrüche. I: Operationen am frischen und verschlepten Knochennbruch. Springer, Berlin 55. Lambotte A (1907) L’ intervention opératoire dans les fractures récentes et anciennes envisagées particuliérement du point de vue de l’ostéosynthèse. Lambertin, Brussels 56. Lambotte A (1913) Chirurgie opératoire des fractures. Masson, Paris 123 1396 57. Lane WA (1893) On the advantage of the steel screw in the treatment of ununited fractures. Lancet 142:1500–1501 58. Lane WA (1895) Some clinical observations on the principles involved in the surgery of fractures. Clin J 5:392–400 59. Lane WA (1893–1894) A method of treating simple oblique fractures of the tibia and Wbula more eYcient than those in common use. Trans Clin Soc London 27:167–175 60. Lane WA (1905) The operative treatment of fractures. Medical publishing Co, London 61. Lane WA (1907) Clinical remarks on the operative treatment of fractures. Brit Med J 1:1037–1038 62. Lane WA (1909) The operative treatment of fractures. Ann Surg 50:1106–1113 63. Lane WA (1914) The operative treatment of fractures, 2nd edn. Medical Publishing Co, London 64. Lilienthal H (1912) Safety in the operative Wxation of infected fractures of long bones. Ann Surg 56:185–191 65. Lister J (1883) An address on the treatment of fracture of the patella. Br Med J 855–860 66. Malgaigne JF (1847) Traité des fractures et des luxations. JB Baillière, Paris 67. Malgaigne JF (1855) Traité des fractures et des luxations. Atlas de XXX planches. JB Baillière, Paris 68. Malgaigne JF (1850) Die Knochenbrüche und Verrenkungen. Erster Band: Knochenbrüche. Rieger’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 69. Malgaigne JF (1859) A treatise on fractures. Lippincott, Philadelphia 70. Martin E (1906) The open treatment of fractures. Surg Gyn Obst 3:258–271 71. Meyer W (1893) Old ununited intracapsular fracture of neck of femur treated by nail Wxation. Ann Surg 18:30–32 72. Milne R (1913) Remarks. Clin JB Murphy 2:229–234 73. MostoW SB (2005) Who’s who in orthopaedics?. Springer, London 74. Nicolaysen J (1897) Lidt om Diagnosen og Behandlingen af Fractura Colli Femoris. Nordiskt Medicinskt Arkiv 8:1–19 75. Nicola T (1945) Atlas of surgical approaches to bones and joints. The Macmillan Company, New York 76. Niehans P (1904) Zur Fracturbehandlung durch temporäre Annagelung. Arch Klin Chir 73:167–178 77. Parham FW (1916) Circular constriction in the treatment of fractures of the long bones. Surg Gyn Obst 23:541–544 78. Parkhill C (1897) A new apparatus for Wxation of bones after resection and in fractures with a tendency to displacement. Trans Am Surg Assoc 15:251–256 79. Parkhill C (1898) Further observations regarding the use of the bone-clamp in ununited fractures, fractures with malunion, and recent fractures with a tendency to displacement. Ann Surg 28:552–570 80. Peltier LF (1988) The treatment of forearm fractures with pins. Professor Georg Schöne. Clin Orthop Rel Res 234:2–4 81. Peltier LF (1990) Fractures: a history and iconography of their treatment. Norman Publishing, San Francisco 123 View publication stats Arch Orthop Trauma Surg (2010) 130:1385–1396 82. Povacz E (2007) Geschichte der Unfallchirurgie. 2 AuXage. Springer, Heidelberg 83. Preston ME (1914) New appliance for the internal Wxation of fractures of the femoral neck. Surg Gyn Obstet 18:260–261 84. Preston ME (1916) Conservatism in the operative treatment of fractures. Colo Med 13:83–88 85. Putti V (1914) Un nuovo metodo di osteosintesi. Clin Chir 22:1021–1024 86. Riedinger F (1881) Ueber Pseudarthrosen am Vorderarm mit Bemerkungen über das Schicksal implantierter Elfbein- und Knochenstifte. Arch Klin Chir 26:985–993 87. Schatzker J (1996) Osteosynthesis in trauma. Int Orthop (SICOT) 20:244–252 88. Schlich T (2002) Surgery, science and industry. A revolution in fracture care, 1950s–1990s. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 89. Schöne G (1913) Zur Behandlung von Vorderarmfrakturen mit Bolzung. Münch Med Wschr 60:2327–2328 90. Senn N (1883) Fractures of the neck of the femur. Trans Am Surg Assoc 1:333–453 91. Senn N (1889) Experimental surgery. Chicago 92. Senn N (1893) A new method of direct Wxation of the fragments in compound and ununited fractures. Ann Surg 18:125–151 93. Senftleben H (1858) Beiträge zur Kenntinss der Frakturen an den Gelenken. Annalen des Charité-Krankenhauses 8:98–143 94. Sherman HM, Tait D (1914) Fractures near joints. Fractures into joint. Surg Gyn Obst 19:131–141 95. Sherman WO (1912) Vanadium steel bone plates and screws. Surg Gyn Obst 14:629–634 96. Sherman WO (1926) Operative treatment of fractures of the shaft of the femur with maximum Wxation. J Bone Joint Surg 8:494– 503 97. Souttar HS (1913) A method for the mechanical Wxation of transverse fractures. Ann Surg 58:653–655 98. Steinbach LW (1900) On the use of Wxation plates in the treatment of fractures of the leg. Ann Surg 31:436–442 99. Thompson JE (1918) Anatomical methods of approach in operations on the long bones of the extremities. Ann Surg 68:309–329 100. Van Meter SD (1911) The open treatment of fractures. J Am Med Assoc 56:863–867 101. Venable CS, Stuck WG (1947) The internal Wxation of fractures. Thomas, SpringWeld 102. Volkmann von R (1878) Die Behandlung der complicierten Fracturen. In: Volkmann R (ed) Sammlung Klinischer Vorträge in Verbindung mit Deutschen Klinikern. Bd II, Nr 117,118. Breitkopf und Härtel, Leipzig, pp 923–976 103. Watson-Jones R, Adams JC,. Bonnin JG, Burrows HJ, King T, Nicoll EA, Palmer I, vom Saal F, Smith H, Trevor D, VaughanJackson O J, Le Vay AD (1950) Medullary nailing of fractures after Wfty years. J Bone Joint Surg B 32:694–729 104. Ch Weisser (2001) Fritz König (1866–1952) Wegbereiter der Osteosynthese und seine EinXüsse auf die Unfalheilkunde. Zenbtralbl Chir 126:237–242