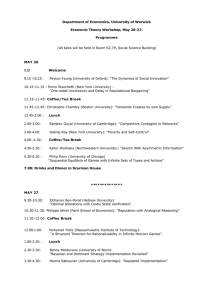

18 hindustantimes SUNDAY HINDUSTAN TIMES, MU MBAI MAY 2 6, 2019 Variety ONLINE GAMING REVENUES HAVE NEARLY DOUBLED IN INDIA OVER THE PAST FOUR YEARS, REACHING ₹43.8 BILLION IN 2018 THE NEXT LEVEL UP Independent gaming studios are creating videogames with desi plots based in music, poetry, myth HOW MANY COFFEES ARE REALLY IN YOUR CUP? When you think beverages and India, you think tea. Maybe wine. But India is currently the seventh largest coffee bean producer in the world! And there are Indian coffees so sought-after in foreign markets that they’re hard to find here at home. According to the Coffee Board of India (CBoI), we produce about 3.1 lakh tonnes of coffee a year. Most, and the best, is exported. Six Indian varieties were recently awarded the Geographical Indicator (GI) tag by the Government of India, meaning that their names can only be ascribed to beans from those specific regions. Here’s a look at the six GI tagged varieties, and the brands where you might encounter them. n Plantation workers in Wayanad. PHOTOS: ISTOCK Anesha George n n Zainuddeen Fahadh, 29, founder of Ogre Head Studio, was 19 when he left home in Mumbai to pursue his dream of becoming a game developer. anesha.george@hindustantimes.com hen a boy is sacrificed by a group of robed men, he rises from the ashes as a demonic form, vowing vengeance and looking like an Indianised version of Hellboy. The trailer for Asura, a videogame released in 2017, looks like a scene from an animated Bollywood mythological drama, complete with rich visuals and a Hindi narrative. Created by Ogre Head Studio, a fivemember team of independent gamers based in Hyderabad, Asura has won nine awards so far, including Nasscom Game of the Year, 2017. Elsewhere in the field of Indian indie gaming, drought-stricken villages must be linked with their river, crumbling cities revived and forgotten tales decoded in museums inspired by poetry. The companies creating these games include Ogre Head, Holy Cow Productions in Bengaluru, a two-person team in Chala, Gujarat, that makes up Studio Oleomingus, and Nodding Heads Games in Pune, all trying to put a slice of India out on global platforms like Steam and GOG.com. “When we think of Indian games, we think of merchandising games based on films like Dhoom and Baahubali, where the script is not original and there is barely any plot progression, so indie games like Asura are a breath of fresh air,” says Abdullah Faiz, 23, an avid gamer based in Mumbai. It’s mainly the really avid gamers that will pay for these indie games, but in absolute W BABA BUDANGIRI & CHIKMAGALUR ARABICA: DESI MOCHA numbers, it’s nu t’ still a large market. Online gaming revenues (typically, sums paid to download a game or for in-game purchases) have nearly doubled in India over the past four years, reaching ₹43.8 billion in 2018, according to a KPMG report released in March. “Gaming companies are emerging in Tier 2 and Tier 3 cities, because of affordable smartphones, high-speed internet and low data prices,” says Ajay Kumar, a professor at Christ College, Bengaluru, currently pursuing a PhD in the political economy of videogame production in India. DAMS, RIVERS, POETRY “In India, there is a story waiting to be told in every corner and videogames are a unique way to tell them,” says Avichal Singh, 28, co-founder of Nodding Heads. Their project, Raji: An Ancient Epic, is a puzzle and a combat game that is slated for release on Steam in early 2020, and follows a young girl searching for her brother who has been taken hostage by a demon king. In Mystic Pillars by Holy Cow, mathbased spatial awareness puzzles help get a river flowing again, in a drought-hit and once-prosperous ancient village. And in A Museum of Dubious Splendours by Studio Oleomingus, Dhruv Jani, 30, plays on surrealist interpretations of post-colonial India. A fictional traveller discovers stories written by a poet, and the player must find his way through displays like a giant tubes of toothpaste, knives and worn-out shoes — and unravel the stories that unfold within each gallery. “I grew up in Dharampur in Gujarat, a city with a peculiar colonial legacy which is evident in its crumbling havelis and temples with Portuguese architecture. The game is loosely based on those memories,” Jani says. “It offers a mix of folklore, literary writing and computational logic.” ZERO-SUM GAMES The big problems facing the indie gaming market are funding and visibility. “Getting investors who prioritise creative content is the biggest hurdle,” says game developer Mithun Balraj, 27. “Brilliant ideas being shelved for a lack of funding.” Zainuddeen Fahadh, 29, founder of Ogre Head Studio, was 19 when he left home in Mumbai to pursue his dream of becoming a game developer. “My co-founder Neeraj Kumar and I borrowed ₹6 lakh from our very supportive families to build the prototype of Asura,” he says. They started providing game design services on the side to finish the project. The founders of Nodding Heads Games sold their own assets to raise money. It was only in March that international gaming platform Super.com became interested in their project, Raji. Since most indie developers are also catering to a global audience, there’s a polish to the designs and narratives, says former Nasscom gaming forum head, Shruti Verma, now business operations head of the subcontinent for Unity, a gaming software company. “A lot of the developers are very passionate and are hence great artistes but lack business acumen to market and push their products, so we need to create an ecosystem for them with mentorship programmes and business incubation facilities.” n (Top) A still from Asura, the hackand-slash mythbased videogame by Ogre Head Studio, Hyderabad. (Above) A Museum of Dubious Splendours has players unravel stories as they make their way through a museum with surreal exhibits like a giant tube of toothpaste. The Baba Budangiri hills in Chikmagalur, Karnataka, are where coffee was first grown in the country. According to legend, seven coffee beans were smuggled here from Yemen in the 17th century, hidden in the tunic of a Sufi saint named Baba Budan. TASTE NOTES: Intensity and clarity of a rich mocha flavour USED BY: KC Roasters, Dope Coffee Roasters ARAKU VALLEY: THE DESI EXPAT Getting your hand on a cup of Araku Valley coffee might be easier in Paris than in India. This complexly flavoured bean is grow on the borders of Orissa and Andhra Pradesh, by tribals who follow traditional practices of apus, most growing. As with the Ratnagiri Hapus of it is exported. TASTE NOTES: Exhibits bright citric flavours and striking aromaa with a note of chocolate, full body and sweet finish WAYANAD ROBUSTA: INSTANT BEAN The rich laterite soil of low-lying Wayanad in Kerala is excellent for growing Robusta beans. According to the CBoI, Wayanad produces 90% of the state’s coffee. Filter coffees are usually a blend of Robusta and Arabica, combined with chicory. TASTE NOTES: Bitter, pungent, but with a mild flavour and full body USED BY: A number of instant coffee and filter coffee brands COORG ARABICA: SOUTHERN STAPLE Coorg is the largest coffee-growing district in the country. The Coorg Arabica, cultivated at high altitudes, exhibits balanced flavours that are best extracted through a medium roast and hot brew. TASSTE NOTES: A well-balanced and mildly sweet taste with subtle m body, low acidic levels and a b chocolatey aftertaste USED BY: Dope Coffee Roasters, B Tokai Roasters Blue USED IN INDIA BY: Araku Valley Coffee House in Vishakapatnam MONSOONED MALABAR The Monsooned Malabar was identified tifi d as a specialty i lt coffee ff by the CBoI in the 1960s. The bean is left to soak up the moisture laden winds of the Western Ghats during the monsoon, to replicate the conditions created during its rocky voyage from India to Europe centuries ago. As the story goes, owing to the monsoon winds en route, the swollen beans at the end of the journey acquired special characteristics. TASTE NOTES: Mellow, musty and fruity-flowery flavour, mildly aromatic and reduced acidity USED BY: Marc’s Coffees, Dope Coffee Roasters, The Coffee Co NATASHA REGO NOWSTREAMING SHWETA TRIPATHI ON WORK, HER PARENTS, AND BEING DIFFERENT WOMEN ‘I’D LOVE TO PLAY AN OLDER WOMAN, JUST FOR CONTRAST’ Dipanjan Sinha n dipanjan.sinha@htlive.com ou probably know her as the girl from Masaan (2015). That film won multiple accolades, including at Cannes, and two years later, Shweta Tripathi’s reputation was sealed with her turn in the critically acclaimed Haraamkhor. Tripathi turned another corner last month, with the release of Season 2 of the Amazon Prime Original, Laakhon Mein Ek. Season 1 dealt with the coaching class industry. Season 2 follows the challenges of a young doctor on a rural assignment. It’s a raw, rugged tale and Tripathi is its star. We sat down with the 33-year-old to talk career choices, big screen vs small, and being many women all at once. Y What has the response been like to the release of Laakhon Mein Ek? This has been my favourite project until now. Even while shooting it, I knew we were making something special. When your work is out it definitely matters what others think — friends, family, people from the industry. But with this series I was so content that it did not matter at all. What drew you to the role of the young Dr Shreya Pathare? What kind of research went into getting into character? One thing that helped a lot was the script. The director Abhishek Sengupta and [the show’s creator] Biswa Kalyan Rath had spoken to many doctors and that reflected in the script. My research was mainly in two parts — the professional and the psychological. For the professional part, I keenly followed the way doctors carry themselves, carry their stethoscope, the difference in tone when they speak with a patient and when they are speaking with friends. And then there was the psychological part. Can a doctor show emotion? What is the emotional toll that this job really takes? I interacted with doctors — how do they feel at the end of a bad day, how do they spend their free time. I did not want a doctor to say, this is not what doctors are like. So it felt special when doctors called me to thank me for how accurately the story of their lives was told. You played a schoolgirl in Haraamkhor. You’re constantly playing women much younger than you are... In fact, the oldest character I have played is Dr Pathare, who’s 24. It’s just worked out like that. Directors don’t seem to worry about my age if I fit into the character. Now I find it easier to play younger characters. › your parents think about your shows? Well, people do recognise me on the streets and come up to talk. This happens a lot in Uttar Pradesh, where they identify me with the roles I played in Mirzapur and Masaan, Initially, I used to be very restrained in public. But now I am just myself, a little more responsible. It mostly feels good when people recognise you but sometimes it can get a little tiring when you want to be by yourself or are in a low mood. At home things haven’t changed much. My parents and my in-laws are ardent followers of all my work, even my interviews. They are often among the first to watch and give feedback. But with all this I always manage to make time for my two important hobbies of reading and watching films. Doing starkly different characters gives you access to worlds different from your own. After Gone Kesh, a story about a girl with alopecia, the idea of beauty gained a different meaning for me. In Haraamkhor, I couldn’t figure why this schoolgirl would fall in love with a teacher so not right for her. As an actor, you realise you just cannot be judgmental. Does critical feedback affect you? SHWETA TRIPATHI, seen here in a still from Laakhon Mein Ek There is a simplicity to things when you are young. When Sandhya [from Haraamkhor] falls in love, she doesn’t overthink it. A character my age would ask practical questions. But at that age, when you’re in love, you’re in love. I would love to play a character much older than I am, just for the contrast. You play women who inhabit very different worlds. What is that like? These characters make you explore lives that are very different from yours and make you more sensitive. After Gone Kesh (in 2019), a story about a girl with alopecia, the idea of beauty gained a different meaning for me. In Haraamkhor, I couldn’t figure why this schoolgirl would fall in love with a teacher who was so not right for her. To understand the character, you start thinking about her life. As an actor, you realise you just cannot be judgmental. How has your everyday life changed? What do I do not get overwhelmed by criticism or praise. I try to take it in my stride and pick up anything useful. If we start getting affected by all kinds of opinion, given the number of people who watch our work, it will be difficult to function. Which is your preferred platform, the big screen or small? The idea of being shown on the big screen is still very special but the reach of OTT is amazing. The series format is also more challenging, considering the sheer length. How do you maintain consistency of character from one season to the next and the next? We can say that talent has a little more opportunity now. PRINTED AND DISTRIBUTED BY PRESSREADER PressReader.com +1 604 278 4604 ORIGINAL COPY . ORIGINAL COPY . ORIGINAL COPY . ORIGINAL COPY . ORIGINAL COPY . ORIGINAL COPY COPYRIGHT AND PROTECTED BY APPLICABLE LAW