A Comparison of Three Imerging Theories of the Policy Process

advertisement

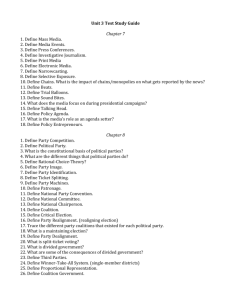

University of Utah A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process Author(s): Edella Schlager and William Blomquist Source: Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 3 (Sep., 1996), pp. 651-672 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of the University of Utah Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/449103 Accessed: 24-11-2018 10:25 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/449103?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Sage Publications, Inc., University of Utah are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Political Research Quarterly This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms FIELD ESSAY A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process EDELLA SCHLAGER, UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA WILLIAM BLOMQUIST, INDIANA UNIVERSITY, INDIANAPOLIS In an earlier review of political theories of the policy process, Sabatier (1991) challenged political scientists and policy scholars to improve theoretical understanding of policy processes. This essay responds by comparing and building upon three emerging theoretical frameworks: Sabatier's advocacy coalitions framework (ACF), institutional rational choice (IRC), and Moe's political theory of bureaucracy, which he calls the politics of structural choice (SC). The frameworks are compared using six criteria: (1) the bound- aries of inquiry; (2) the model of the individual; (3) the roles of information and beliefs in decision making and strategy; (4) the nature and role of groups; (5) the concept of levels of action; and (6) the ability to explain action at various stages of the policy process. Comparison reveals that each framework has promising components, but each remains short of provid- ing a full explanation of the processes of policy formation and change. Directions for future theory development and empirical examination are discussed. Developing logical, empirically supported political theories of the public polic process remains an important enterprise within political science. Many case studies of policy making generate useful insights about elements that a politi cal theory of the policy process must account for. Case studies, however, are not general theoretical explanations of how political actors create, implement and change public policies in order to advance their own purposes and re- spond to perceived problems. Rigorous theoretical work accounts for specific actors, such as legislators, or specific stages of the policy process, such a agenda setting, but does not attempt to address the public policy process in NOTE: The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments of previous readers, especially Hank Jenkins Smith, H. Brinton Milward, Laurence O'Toole, Hal Rainey, Paul Sabatier, John Geer and the anonymous reviewers for this journal. 651 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly its entirety. Sabatier (1991) and Moe (1990a, b) encourage colleagues within the discipline to make further progress in building theories of the policy pro- cess. Their own work contributes to this enterprise. Sabatier and several col- leagues fashioned the advocacy coalitions (AC) framework. Moe developed the "politics of structural choice" (SC) as a promising basis for explaining why public policies and organizations work as they do. Sabatier recommends attention to the institutional rational choice (IRC) approach associated with Elinor Ostrom and colleagues at the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. While these three approaches do not exhaust the activity in the field, this essay focuses upon them because they represent relatively well-developed frameworks which show promise of blossoming into general political theories of the policy process. Like many fields within political science, that of theories of the policy process is hard to delineate firmly because it overlaps with and draws upon several related endeavors. Within the field, important advances include the articulation of the stages of the policy process Oones 1977; Eyestone 1978; Anderson 1979); the path-breaking work on agenda setting by Kingdon (1984) and Baumgartner and Jones (1993), and the distinction among policy types and the politics surrounding them (Lowi 1964; Wilson 1980; Gormley 1983). Comparative policy research, including comparative research involving the American states (Dye 1966; Sharkansky 1968), has shed light on important factors in the external environment of the political system that affect policymaking and policy outcomes, but to date comparative policy research has produced a larger number of anthropological, sociological, and economic explanations of policymaking and policy outcomes than political ones. The work of political scientists studying particular institutions and actors involved in the policy process also feeds the development of political theories of the policy process. Certainly, the development of theories of legislator behavior (Mayhew 1974), bureaucrat behavior (Niskanen 1971), lobbyist behavior (Salisbury 1986; Rosenthal 1993), and the behavior of policy entrepreneurs (Schneider, Teske, and Mintrom 1995) inform us that any truly political theory of the policy process must account for the fact that political actors engage in the policy process not only-indeed, perhaps not primarily-in order to respond to perceived social problems, but also to advance their own political interests and careers. Recent contri- butions in the area of political control of the bureaucracy (Calvert, McCubbins, and Weingast 1989; Macey 1992; McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast 1989; Wood and Waterman 1991) overlap with and contribute to the development of political theories of the policy process that would account for policy implementation and not just policy formulation and adoption. These connections to other fields of research in political science do not, in our view, overshadow the importance of the enterprise of developing more 652 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process general theories of the policy process, theories that can account for the multiple facets and actors that define and motivate the policy process. An update and overview of that field of endeavor is our purpose here. In this essay, we offer a methodological comparison of the IRC, SC, and AC approaches. We present a brief synopsis of each, then compare them on several important aspects. In this comparison, the features of each approach help to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the other two. We conclude with suggestions for further theory development and research. APPROACHES TO POLICY PROCESSES The goal of a political theory of the policy process is to explain how interested political actors interact within political institutions to produce, implement, evaluate, and revise public policies. The explanations offered by the three approaches presented here proceed toward that goal from different starting points, and overlap in places while diverging in others. Ostrom and Institutional Rational Choice IRC theorists conceive of public policies as institutional arrangements-rules permitting, requiring, or forbidding actions on the part of citizens and public officials. Policy change results from actions by rational individuals trying to improve their circumstances by altering institutional arrangements (Bromley 1989: 252). IRC explanations of institutional change entail some presumptions about the individual actors and key critical characteristics of the decision situation in which the actors behave. An adequate model of the individual actors must specify their: (1) resources; (2) ability to process information; (3) valuation of outcomes and actions; and (4) criteria for selecting actions (Ostrom 1990: 132; 1991b: 241). Actors' strategy choices are guided by their perceptions of expected benefits and costs, conditioned by the decision situation. The structure of a decision situation includes (1) institutional arrangements-rules-that define what actions are permitted, required, and forbidden; (2) attributes of the physical world being acted upon; and (3) characteristics of the community within which action is proceeding. Since in most cases, actors cannot readily change the characteristics of the community or the relevant attributes of the world, they direct their efforts to realize their prefer- ences and improve their situations at changing institutional arrangements. Thus, IRC defines policy change in terms of actions taken to change insti- tutional arrangements within a decision situation that is partially shaped by institutional arrangements. The IRC framework addresses this apparent circularity with the concept of levels of action. Actors operate within rules, but may also be able to establish and modify rules. Actions taken within the existing 653 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly rule set are regarded as one level of action; actions taken to modify the rule set are regarded as another level of action. Actions of the latter type represent "institutional change, as contrasted to action within institutional constraints" (Ostrom 1991a: 8). There are three levels of action: (1) operational, having to do with the direct actions of individuals in relating to each other and the physical world; (2) collective-choice, the level at which individuals establish the rules that govern their operational-level actions; and (3) constitutional, the level at which individuals establish the rules and procedures for taking authoritative collective decisions. The same actor or actors may move between levels of action. Much of the time, actors seek their best outcomes within a given set of rules. At other times, actors try to change the rules in ways that make their preferred outcomes more likely and dispreferred outcomes less likely. IRC conceives of policy change as actions at the collective choice and constitutional levels to change institutional arrangements. Ostrom advances the IRC framework to correct what she views as a shortcoming of the policy literature-the presumption that there are only two types of institutional arrangements for resolving collective problems, markets based on individual private property rights or state-centered public bureaucracies (Ostrom 1990). She and others use the framework to explore the institutional space between these two extremes: in particular, local-level, self-governing organizations designed by users to manage common-pool resources (e.g., Ostrom, Gardener, and Walker 1994). Substantial empirical work based on the IRC framework (Schlager 1990; Tang 1992; Blomquist 1992; Lam 1994) demonstrates that common-pool resource users are not trapped in an inevitable "tragedy of the commons" from which they can be rescued only by bureaucratic control (Hardin 1968) or privatization (Welch 1983). In many situations resource users have operated at the constitutional and collectivechoice levels to change the rules governing their use of the commons-i.e., they have accomplished policy change. Moe and the Politics of Structural Choice Moe's politics of structural choice also conceives of public policies as institutional arrangements. He acknowledges that institutional changes can be viewed as the results of rational individuals' efforts to overcome collective action problems and cooperate for mutual gains (Moe 1990b: 213). Moe, however, proposes that this mainly economic theory of institutional development should be supplemented by a political theory that views institutional development and modification as political processes involving conflict over power (1990a: 119). Moe views the formation of public policies (and the organizations that implement them) as arising from the interaction of interest groups, politi654 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process cians, and bureaucrats within the context of democratic politics (1990a: 131). His "decision situation" includes a two-tiered hierarchy of political action, in which "one tier is the internal hierarchy of the agency, the other is the political control structure linking it to politicians and groups" (1990a: 122). Taking for granted that the principal actors in the policy process are groups-and setting aside the issue of group formation (1990a: 130)-Moe explores processes in which groups struggle to gain control of government in order to achieve their preferred arrangements and policies. Because of the political environment in which structural choice occurs, however, the resulting arrangements are not necessarily designed to be efficient or even effective. Those who gain control of public authority-politicians and their interestgroup allies with whom they trade the use of formal decision-making authority in exchange for political support-may do so only temporarily. In a fully developed democracy, today's winners know that they may be tomorrow's los- ers, unable to exercise public authority (Moe 1990b: 227). Additional concerns arise from the principal-agent problem-the prospect that bureaucrats will fail to implement or enforce designed policies while and after the group is in control. These considerations enter into the political calculus of those in control of government, when they make policy by designing or modifying institutional arrangements. For instance, politicians "establish administrative agencies in ways that reduce the chance that future changes in the political landscape will upset the terms of the original understanding among the relevant politi- cal actors" (Macey 1992: 93). They may specify in detail how an agency will conduct its business, leaving as little discretion as possible to bureaucrats and future political officeholders. They may insulate the agency from sunset or reauthorization provisions that would enhance future political oversight. These and other tools of institutional design can shield an agency and the policies it implements from political interference if or when the currently dominant group loses power. Political compromise also affects institutional design. Particularly in Ameri- can politics, with its separation of powers and federalism, an individual or a single interest group is almost never powerful enough alone to establish its desired policy. Often, to gain even a portion of what it wants, those seeking political control must engage in compromise, even with adversaries. Adversaries who gain a say in institutional design are likely to (1) impose conditions that cripple institutions and policies they oppose, and (2) pursue rules that open up agencies and policies to more direct political control, in anticipation of a future return to political power (Moe 1990a: 127). The SC framework's ironic prediction is that political actors' preoccupa- tion with political control leads them to make or accept choices in the 655 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly policymaking process that so divorce policy design from policy desire that their policy goals are not achieved through the processes and structures they adopt (Moe 1990b: 228). Direct links between institutional means and policy ends cannot be assumed, because of the politics of structural choice. Where do specific political actors, such as legislators, interest groups, and the president, fit within this framework? For Moe (1990a, 1990b), the catalytic actors are organized interest groups. Organized groups are interested in, and pay careful attention to, not only the content of policies but the structure of the organizations that will implement the policies. Given the twin pressures of political compromise and political uncertainty, organized groups want "bureaucracy that is highly 'bureaucratic,' buried in formal rules and requirements that undermine effectiveness and insulate against democratic control" (Moe and Wilson 1994: 5). Will elected officials-legislators and presidents who make structural decisions-accede to the groups' demands? Moe suggests that legislators will be most responsive to organized inter- ests because of their "almost paranoid concern for reelection," and because most of the time legislators gain little by acting contrary to the demands of organized interests (Moe and Wilson 1994: 8). Presidents, however, are another matter. Presidents face a different set of pressures, such as a national constituency. Citizens hold them responsible for "virtually every aspect of national performance" (Moe and Wilson 1994: 11). Consequently, presidents want bureaucracies that are relatively effective and that they can control, not bureaucracies insulated from democratic control. The struggle for structural choice occurs among organized interests, their legislative supporters, and the president, with losers in the legislative arena aligning themselves with the president in hopes of more favorable outcomes as the executive branch implements and interprets legislative decisions. Although Moe's work remains in its early stages, its latest installments offer the possibility of a move away from political scientists' strong attachment to Congress as the policy actor in Ameri- can politics, toward a more explicit inclusion of other actors such as organized groups and the president. Sabatier and Advocacy Coalitions Sabatier advocates an "advocacy coalition" (AC) framework that highlights multiple major actors and other variables at work in the process of policy change. Policy change, normally occurring over a period of a decade or more, is viewed as a function of: (1) the interaction of competing advocacy coalitions within a policy subsystem; (2) changes external to the subsystem (e.g., in socioeconomic conditions); (3) the effects of relatively stable system parameters (e.g., constitutional rules, basic social structure). The policy subsystem is the unit of analysis for understanding policy change, with the other 656 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process two sets of factors constraining and affecting it. A policy subsystem consists of actors from "public and private organizations who are actively concerned with a policy problem" (Sabatier 1988: 131). Advocacy coalitions group the actors within a policy subsystem. Those coalitions consist of individuals "who share a particular belief system-i.e., a set of basic values, causal assumptions, and problem perceptions-and who show a non-trivial degree of coordinated activity over time" (Sabatier 1988: 139). Through its broad definition of advocacy coalitions the AC framework firmly anchors itself in a pluralistic notion of politics. The shared belief system that defines an advocacy coalition contains "fun- damental normative axioms," plus beliefs about policies to achieve those axioms (Sabatier 1988: 144). The belief system contains a coalition's understanding of the connections between institutional structures and policies and their effectiveness for realizing the coalition's goals. Members of coalitions act in concert, based on their belief systems, "to manipulate the rules of various governmental institutions to achieve" shared goals (Sabatier 1991: 153). Their methods of operation include: (1) developing and using information in an advocacy mode to persuade decision-makers to adopt policy alternatives supported by the coalition; (2) manipulating the choice of decision-making forum; and (3) supporting public officials in positions of public authority who share their views or may even be members of the coalition. While coalitions compete for control over public authority, typically there is a dominant coalition and one or two minor coalitions. Major policy changes occur in the following ways: (1) coalitions engage in compromise (often mediated by a "policy broker") to gain passage of desired policies; (2) "external perturbations," such as changes in socioeconomic conditions, shift coalition resources and/or perceptions of policy problems; (3) trial-and-error learning from the adoption, implementation, and evaluation of government programs modify belief systems; or (4) one or more coalitions' belief systems change in an "enlightenment" episode resulting from the accumulation of policy information. The AC framework emphasizes the role of information and learning as motivating factors in the process of policy change. As a result, the policy pro- cess is conceived as a continuous and "iterative process of policy formulation, problematic implementation, and struggles over reformulation," rather than a unidirectional progression implied by the stages heuristic (Sabatier 1988: 130). Only core elements of the relatively large and complex AC framework have been quantitatively tested, although numerous case studies have critically explored much of the framework (see Sabatier andJenkins-Smith 1993a). For instance, relatively stable and longlasting coalitions opposed one another 657 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly in airline regulation and deregulation debates, with the coalition favoring deregulation taking advantage of the opportunities provided by exogenous events, such as record rates of inflation, to promote its preferred policies (Brown and Stewart 1993). Access and use of professional fora, such as U.S. Senate subcommittee hearings, promoted policy learning as each side presented and supported its position. In the process, the arguments in support of regulation were discredited and the central policy question changed from whether deregulation should occur to how it would occur. Quantitative tests of the AC framework, based on content analysis of tes- timony at public hearings, support its core elements. Testimony at congres- sional hearings on the U.S. offshore oil leasing program, and testimony at hearings regarding land use and water quality at Lake Tahoe, support the posited structure of belief systems, the stability and longevity of coalitions, and the importance of exogenous events for promoting policy change (Jenkins- Smith and St. Clair 1993; Sabatier and Brasher 1993). Overall, the AC framework appears to be tailored to explaining policy change over a period of decades. It emphasizes policy changes resulting from changing preference or beliefs on the part of critical actors, as opposed to explaining change as a consequence of the appearance of new actors with different sets of preferences. COMPARING THE APPROACHES There are several differences among the theoretical frameworks. They can, however, be compared systematically through a review based on six criteria: (1) the boundaries of inquiry; (2) the model of the individual; (3) the roles of information and beliefs in decision making and strategy; (4) the nature and role of groups; (5) the concept of levels of action; and (6) the ability to explain action at various stages of the policy process. We believe that these criteria represent essential elements of any proposed political theory of the policy process, and provide critical points of comparison for the three approaches discussed here. The first two criteria, boundaries of inquiry and model of the individual, are important for highlighting methodological similarities and differences-in other words, whether and to what extent the theoretical approaches are attempting to explain the same phenomena from the same starting point. Criteria (3), (4), and (5) all capture a particular emphasis of one of the three frameworks and examines its treatment by the others-AC's focus on information and beliefs, Moe's use of groups as catalytic political actors, and IRC's conception of the levels of action. The sixth criterion returns to the frameworks' potential as political theories of the policy process, as opposed to their ability to explicate some more limited aspect of public policy 658 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process Table 1 encapsulates the comparison of the three approaches on those six criteria. The narrative that follows elaborates on the comparison. The Boundaries of Inquiry Each theoretical approach includes boundaries of inquiry, separating endogenous elements requiring explanation from exogenous elements that are given. The IRC approach permits the analyst to define the boundaries of inquiry, as TABLE 1 COMPARING THE APPROACHES Institutional Criteria Rational Choice Structural Choice Advocacy Coalitions Boundaries The decision Typically, a public Policy subsystem of Inquiry stiatuation and organization plus its organized around individuals creators, benefactors policy problems and administrators Model of the Intendedly but Substantively rational Procedurally rational Individual boundedly rational maximizer seeking acting on information problem-solver power and beliefs Uncertainty, Actors use search and Actors' behavior Accumulation and use Information and trial-and-error driven largely by of information a key Beliefs learning to reduce political uncertainty, element of policy uncertainty Beliefs Interests emphasized change. Actors' enter in as attributes over beliefs as beliefs serve as of the community, motivations for perceptual filters i affecting the costs & actors' behavior their receipt of benefits of options information, but information can also change beliefs Nature and Role Groups are not central Groups are central to Coalitions, which of Groups to IRC explanations political action, but include interest and collective action their formation is groups, are central barriers to group assumed rather than actors and cohere formation emphasized explained. Groups and around beliefs. politicians exchange Process of coalition political support for formation is assumed favorable policies rather than explained Levels of Action Explicitly made part Implicitly included in Implicitly part of of actors' coalitions' explanation; however, strategic behavior in strategic behavior; most of the time, rules attempt to influence policy change of the political game choice of decision conceived as rule assumed fixed making forum change Stages of the Emphasis on problem Emphasis on adoption Emphasis on problem PolicyProcess definition, policy stage definition, policy formulation, formulation, adoption, evaluation evaluation 659 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly long as the analyst specifies the required elements of the decision situation and the model of the individual. An IRC approach could entail explaining a decision or decisions made within an organization, between organizations, or among multiple organizations and actors. The boundaries of the inquiry depend largely on the interests of the analyst. The SC framework's more tightly constrained boundaries of inquiry include a public organization (in many instances an agency), and the interests and interactions of its creators (legislators), its benefactors (interest groups), and its administrator or executive. Policy change and policy implementation arise from control by or compromise among one or more of these actors. Like the AC framework, the SC framework takes the constitutional rules and the structure of formal authority as given, as outside of the scope of inquiry. Sabatier broadens the inquiry to include a policy subsystem. A policy subsystem, organized around a policy problem (e.g., air pollution), includes a potentially broader array of actors involved with that problem. The policy subsystem concept allows the inquiry to encompass multiple public organizations, and to include additional actors such as policy analysts and journalists. In practice, the AC framework has usually focused on a specific government policy and the actors who coalesced around its development. The Model of the Individual The frameworks diverge significantly in their models of the individual actors involved in policy processes. The AC framework is based upon a view of the individual that is substantially different from the one employed in the SC and IRC approaches. The individual in the AC framework is based on Simon's notion of procedural rationality (Simon 1985: 294). The individual engages in limited search processes, makes choices based on his or her subjective representations of the situation, and satisfices. Analysts attempting to understand the individual's behavior must learn about those subjective representations-an individual's perceptions as well as his or her information resources and information-processing capability SC's individual actor is more firmly grounded in economics-a substantively rational, self-interested individual who actively searches for best outcomes. No attention is paid to the internal belief systems of individuals, or to how they gather, process, and synthesize information. Decisions are understood and explained entirely in terms of individuals' assumed preferences or interests and the characteristics of the external situation. The IRC framework, as developed and presented by Ostrom, involves intendedly but boundedly rational individuals. These individuals are not assumed to have perfect information or infallible information-processing abili660 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process ties, but they are capable of learning. In most previous applications, however, IRC explanations have employed substantive rationality-individuals understand their situations and make choices strategically to maximize utility. Practitioners of the AC framework have devoted much of their attention to the inner world of individuals, to the structure and content of their belief systems (Sabatier 1988; Jenkins-Smith 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993a). As an empirical enterprise, instead of assuming individuals' preferences, AC analysts develop and test empirically verifiable hypotheses concerning actors' belief systems. Furthermore, AC's attempt to account for belief systems and how they change over time also highlights the importance of policy learning-something that most models fail to do-elevating it to the status of a critical causal variable. Subsuming the notion of preferences or interests into the concept of belief systems, however, raises two potentially serious shortcomings of the AC framework. First, because belief systems of individual members of an advocacy coalition are considered homogeneous, their individual interests are con- sidered homogeneous. In some situations, however, the interests of the members of an advocacy coalition conflict, even while they continue to share a core set of beliefs. These conflicts among members of an advocacy coalition often contribute to policy change, but this is not one of the sources of policy change identified in current explanations of the framework. By failing to account for the interests or preferences of the individual members of advocacy coalitions, the AC framework cannot explain intra-coalition rifts caused not by differences in policy learning but by underlying differences in interests. In addition, without separately accounting for interests among the factors motivating individuals, the AC framework lacks a basis for predicting or explaining strategic behavior. One is left instead to presume that individuals act naively on the basis of their beliefs, and that they do not misrepresent their policy preferences when attempting to attain more preferred outcomes. These are questionable assumptions in the context of politics. Absent the notion of strategic behavior motivated by interest, the AC framework may not be able to account for the variety of institutional structures found in the public sector. Using a substantively rational model of the individual, on the other hand, Moe's SC approach offers an explanation of how particular organizational struc- tures emerge from the political decision-making process. The SC framework provides a crucial insight that neither the AC nor IRC approaches generateswhy institutional arrangements designed in the political arena seem poorly suited to accomplishing their stated purposes. For AC's procedurally rational coalition members, or IRC's intendedly rational problem-solvers, poor institutional performance is typically due to design error that is (or can be) cor- rected by learning from information through analysis, experience, or 661 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly experimentation. In the explicitly political world described by Moe, interest groups, politicians, and bureaucrats respond strategically to the uncertainty and conflict of their environment by balancing their interest in creating effec- tive institutions with their interest in shielding their creations from potential control by adversaries. Institutional effectiveness is therefore compromised, not incidentally (because the individuals engaged in institutional design had inadequate information or experience), but deliberately. Information and Beliefs The SC and IRC frameworks do not explicitly attend to the role of beliefs. Ostrom argues that any model of the individual must include assumptions about how that individual views and values the world, but there is no exploration within the IRC framework of how different belief systems affect the calculations and strategy selections of the individual. To the extent that "beliefs" enter into the IRC framework at all, they are "attributes of the community" that affect the costs or benefits attached to choice options. By adopting substantive rationality, the SC and IRC frameworks confine the use of information to relatively narrow roles. Individuals with fixed prefer- ences are treated, at least implicitly, as information sponges. They incorporate any relevant information from any source into their decision making. For instance, Moe's interest groups, politicians, and bureaucrats do not "filter" the information they receive from their environment through a system of beliefs that screens some items out while accepting others readily. In both frame- works, individuals' limited information processing capabilities explain the selective incorporation of information in the learning and decision-making processes, not ideological resistance. The AC framework incorporates a much more sophisticated use of infor- mation. For instance, coalitions may base their choice of decision-making forums on their perception of the strength of the substantive, technical policy information that supports their positions. A coalition will favor the highly professionalized forum if it believes that it can prevail on the technical merits, while a coalition with a weaker analytical case will favor a more openly political forum or the intervention of a "policy broker". An advocacy coalition may use information as part of a socialization process, for recruiting and adding members, for reinforcing the views of existing members, and for increasing the congruence of members' perceptions of their goals and policy preferences. People with common understandings of their preferred outcomes are more likely to sustain collective action than people who do not share such understandings and must unite on commonality of interest alone (Miller 1992). 662 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process Belief systems, as information filters, stabilize preferences. This interaction of information and beliefs is a central point of the AC framework. AC's emphasis on values and beliefs supposes that members of an advocacy coalition will readily incorporate information into policy change while resisting or ignoring other information. Actors in the AC framework resist or reject infor- mation that challenges their core beliefs. Core beliefs therefore serve as "perceptual filters" through which information passes before being incorporated into the knowledge of members of an advocacy coalition. The AC framework incorporates the deliberate cultivation and accumulation of information within the array of coalition actions. Indeed, the "advocacy" part of the AC explanation for policy change represents the conviction that coalitions in the policy process devote considerable resources to the development and deployment of policy information that supports their views, and that such activities matter. Policy change in the AC framework occurs less from the successful seizure of control than from the successful pursuit of persuasion: In political systems with dispersed power, [political actors] can seldom develop a majority position through the raw exercise of power. Instead, they must seek to convince other actors of the soundness of their position concerning the problem and the consequences of one or more policy alternatives. (Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier 1993b: 45) The Nature and Role of Groups Groups, alliances, and coalitions are central political actors in the AC and SC frameworks. On the other hand, while Ostrom notes that the "actor" in the IRC framework may be a single individual or a group functioning as a corporate actor, IRC has not accorded a large role to group behavior. It is especially unclear how IRC would deal with the involvement in the policy process of alliances and coalitions, which are something short of a group functioning as a single corporate actor. IRC theorists instead frequently emphasize collective-action barriers and the difficulty of forming and maintaining coordinated activity. In the IRC framework, the mere fact of a set of similarly situated individuals by no means assures that they will work together. This recognition presents a challenge to the AC and SC approaches. Each of those frameworks include coalitions consisting of heterogeneous individuals-legislators, bureaucrats, and interest group leaders at a minimum. Yet both frameworks simply assume coalitions among such actors exist, overlooking problems of coordination and collective action. An individual's self-interest, or the interests of an organization an individual represents, may not coincide with the coalition's interest. Consequently, collective action problems must be 663 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly addressed for coalitions to form. And to remain in existence, those coalitions that do form must develop mechanisms for resolving ongoing social dilemmas that emerge within groups-such as opportunism, information asymmetries, and bargaining over the allocation of benefits produced by the group (Miller 1992). Understanding how potential coalition members achieve coordination is important because institutions matter. The rules, norms, and sanctions coalition members devise to coordinate their actions almost certainly affect the outcomes that coalitions achieve. Understanding the types of coordination mechanisms that are adopted, how well matched those mechanisms are to the environments in which they are used, and how effectively they bind coalition members together should reveal much about the successes and failures of coalitions. This area has been little studied, but is critical for explaining policy outcomes. Levels of Action Of the three, the IRC framework most explicitly addresses and inc the concept of levels of action. Policy actors act within a decision s realize their preferences, or to advance their interests by shifting level of action at which to change rules, including rules defining the public authority. IRC's emphasis on levels of action brings instituti into the realm of what is to be explained. By contrast, the AC framework handles changes in the rules decision situation as exogenously generated perturbations. The work contains some implicit recognition of the levels of action con marily in its discussion of multiple decision-making forums and the that coalitions attempt to influence the choice of decision-making implementing agency in ways that will advantage their side (Heintz a Smith 1988). Sabatier (1993: 28-29) writes, "One of the basic str any coalition is to manipulate the assignment of program responsib that the governmental units that it controls have the most authorit In his presentation of the "politics of structural choice" framew (1990a: 120-21) explicitly assumed fixed rules of the political ga the relevant period. Accordingly, the players in the SC framework over political and administrative control without necessarily shifting of authoritative decision making. On the other hand, in previous w ing to political control and public organizations (e.g., 1987: 240), Mo nizes the importance of strategic decisions taken by political actors c whether and how to try to change the rules of the game, so a "level conception may be compatible with the SC framework Moe present 664 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process Stages of the Policy Process Although Sabatier (1991: 147) argues that the "stages heuristic ... has outlived its usefulness and must be replaced, in large part because it is not a causal theory", it may still be of some use. As Jenkins-Smith and Sabatier (1993a: 2) acknowledge, "The stages heuristic has provided a useful conceptual disaggregation of the complex and varied policy process into manageable segments." A worthwhile political theory of the policy process should explain activity at each stage. The stages concept retains usefulness as a measuring stick for efforts to develop policy theories. In its emphasis on coalition formation and institutional design, the IRC framework focuses primarily on the problem identification, policy formula- tion, and policy evaluation stages. Policy adoption and implementation are problematic, but the IRC framework to date has not been used to explore policy adoption in conflictual settings, and has restricted its analysis of imple- mentation primarily to principal-agent problems. Development of the SC framework so far has focused primarily on policy adoption, at which stage implementation is "hard-wired" through structural choice. The questions Moe has explored have been why and how policies are made. The learning stages of the policy process-problem identification and policy evaluation-have not received as much direct attention. AC theorists have given most of their attention to the learning and advocacy stages of the policy process, emphasizing the role of coalitions and their belief systems in understanding problem definition, the formulation of policy alternatives, and feedback from prior program adoptions. The adoption stage has been explored in terms of the multiple ways in which policy change occurs, including the attention given to the importance of decision-making fo- rums and "policy brokers." Implementation has not been given the same attention. Taken individually each framework attends to multiple stages of the policy process, although not all stages. It may even be said that each framework seems to relate better to some stages than to others. Only when taken together do the frameworks attend to all of the states of the policy process, and to relationships among them. CONCLUSION Each of these political theories usefully moves explanations of the policy process beyond a single policy stage, or a single actor. In so doing, each contributes important pieces to the policy process puzzle. In addition, each presents challenges to, and faces challenges from, the others. The IRC and SC frameworks, based on substantive rationality, challenge the AC framework to ac- 665 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly count for strategic and opportunistic political behavior. The AC framework's more sophisticated incorporation of the roles of information and learning, challenges the other frameworks to consider the ideological filtering of infor- mation, and changes in individuals' beliefs, as mechanisms promoting or inhibiting policy change. The IRC framework's explicit consideration of collective action problems challenges the failure of the AC and SC frameworks to explain how coalitions form and maintain themselves over time. Furthermore, each framework requires further development. In particu- lar, two areas need substantial attention-collective action and institutional complexity. While these two areas do not exhaust the shortcomings of the frameworks, they do represent areas, that if addressed, would achieve substantial theoretical purchase with very little work. The frameworks can, rather easily, accept these changes. First, both the AC and SC frameworks must come to grips with the prob- lems posed by the necessity of collective action. Incorporating theories of collective action would strengthen the basic premises of each framework. For instance, the AC framework's treatment of beliefs as the glue binding coalitions together comes dangerously close to disregarding the lessons of the vari- ous collective action literatures, beginning with the work of Olson (1965). Simply because individuals hold common beliefs does not mean that they will collectively act on those beliefs. For beliefs to act as an important explanatory variable of policy outcomes, beliefs must be linked to individuals' ability to form advocacy coalitions and to act in concert over time (Schlager 1995). In order to form workable coalitions, individuals must overcome a series of collective action problems. Even though members of a potential coalition would agree that each would be better off if together they coordinated their actions, that coordination may not occur because of freeriding problems. Shared beliefs among individuals concerning appropriate policies and desirable outcomes may reduce the costs of overcoming freeriding. Identifying potential coalition partners may be easier, appeals to work together may more likely be heeded, and substantial heterogeneities among individuals, that under other circumstances would impede cooperation, may be muffled by shared beliefs. Forming a coalition is not the end of collective action problems. Members must agree upon a particular policy to pursue, which raises critical distributional issues. There may be a variety of policies that would make each member of a coalition better off. However, each policy likely makes some members of the coalition better off than others. Consequently, reaching agreement on a specific policy, deciding how to allocate the benefits produced by a particular policy, may be difficult to achieve. Coalition members must resolve other distributional issues such as allocating the costs of engaging in collective action, 666 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process i.e., providing meeting space, writing draft legislation, conducting research and writing reports, etc., not to mention gaining consensus on the strategies that the coalition will use to attempt to achieve its policy goals. The more completely a coalition resolves these collection action problems, the more stable, strong, and effective the coalition is likely to be. The consistency, and overlap of individuals' beliefs is likely to support coordination. Thus, while beliefs play a central role in the AC framework as filters of information, as bases for strategy selection, and so forth, beliefs have a much more substantial role to play, a role that can be realized once collective actions issues are admitted into the framework. The SC framework can also be strengthened by paying explicit attention to collective action. No doubt, political uncertainty and political compromise strongly influence the policies a group selects and the strategies a group pursues to realizes its policy goals. The twin pressures of uncertainty and compromise that bear down on a group, however, are mediated by how the group resolved the numerous collective action problems it confronted. For instance, political compromise may shatter a group that could find consensus only on a narrowly defined policy goal. On the other hand, political compromise may play a minor role in the adoption of a particular policy if its supporting coali- tion has largely resolved many of its most pressing collective action issues. It may be sufficiently stable and influential that it need not compromise, or com- promise much, for its policy goals. The structure, stability, and effectiveness of a coalition are a function of whether and how it resolved its collective action problems, and thus how it will respond to political uncertainty and com- promise. This is something that the SC framework fails to account for by simply assuming that groups, or coalitions, exist. Second, both the SC and the IRC frameworks, at least in their applications, fail to account for institutional complexity created by constitutionallevel arrangements such as a separation of powers and federalism as found in the U.S. Such complexity means that a given problem situation does not involve a single federal agency, its congressional overseers, perhaps the presi- dent, and active interest groups, as Moe has focused upon. Instead, a given problem situation is much more likely to include more than a single federal agency, their congressional overseers, perhaps a court, coalitions organized at the national level, a state agency or agencies implementing the policy, perhaps a state's legislators and governor, and coalitions active within the state. While this setting is somewhat more complex than the current SC framework, it immeasurably adds to its explanatory power. Similarly, the AC framework may have been developed with larger-scale, federal-level policymaking in mind. Future efforts to apply the AC framework 667 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly in order to explain policymaking in state and local settings may illuminate shortcomings that have not been revealed heretofore. It remains to be seen, for example, whether the prominent role accorded to scientific and technical analysis by the AC framework exhibits the same significance in policymaking in local jurisdictions. Incorporating subnational actors would also allow greater attention to be paid to policy implementation. The implementation process itself is strongly affected by political uncertainty and compromise, as subnational actors come to grips with placing the policy into -practice. Implementation outcomes in turn affect groups at the national and state levels that are likely to remain active, and the nature and influence of political uncertainty and compromise in subsequent rounds of policy formation. Thus, by accounting for institutional complexity the SC framework is expanded to explicitly include implementation, while the powerful explanatory variables of the SC framework are brought to bear on this area. The issue of addressing institutional complexity is of greater significance to the IRC framework. The framework must prove useful for handling more institutionally complex situations if it is to gain wider acceptance. Applying it to more complex situations, characterized by both cooperation and coercion, and involving multiple actors (corporate as well as individual) and multiple decisions occurring across several decision situations, is not a straightforward task. Analysts may become quickly overwhelmed in attempting to track down dozens of actors and the strategies they pursue in a rich and varied institutional context. Problems emerge in attempting to simplify the analysis, since there are no guidelines informing the analyst when it would make sense to lump similar actors together and treat them as a single actor, or which types of institutional rules (if any) can be safely ignored. This discussion of the frameworks' comparative strengths and weaknessess in handling institutional complexity may raise for some readers another question: whether the frameworks differ also in their applicability to different policy areas, in the sense meant by Lowi (1972). Policies of the regulatory, and especially of the self-regulatory, type may show more signs of the organizationalchoice-for-political-control decision making emphasized by the SC framework. The significance the AC framework places upon coalitions' differing core be- liefs and values may give it an advantage in accounting for redistributive policymaking. The IRC framework has been applied to policies of all types identified by Lowi, but most often to less-conflictual distributive and regulatory ones. We do not believe the shortcomings identified above are fatal to any of the frameworks. In some cases the lessons and insights produced by the various literatures addressed in the introduction can be drawn upon. For instance, 668 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process problems of collective action and methods of resolving such problems are relatively well understood and form the subject of a growing literature in po- litical science and economics. In other cases, such as developing a more satisfactory model of the individual, a model that admits both opportunism and learning, await rich and productive research programs. Regardless of how these issues are resolved within the context of each framework, together they reveal that there is much to be gained by considering the policy process as a whole. REFERENCES Anderson, James E. 1979. Public Policymaking, 2d ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Baumgartner, Frank, and Bryan Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in Ameri- can Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Blomquist, William. 1992. Dividing the Waters: Governing Groundwater in South- ern California. San Francisco: ICS. Bromley, Daniel. 1989. Economic Interests and Institutions: The Conceptual Foun- dations of Public Policy. New York: Basil Blackwell. Brown, Anthony, andJoseph Stewart. 1993. "Competing Advocacy Coalitions, Policy Evolution, and Airline Deregulation." In Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith, eds., Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. Calvert, Randall, Mathew McCubbins, and Barry Weingast. 1989. "A Theory of Political Control and Agency Discretion." American Journal of Political Science 33: 588-611. Dye,Thomas. 1966. Politics Economics, and the Public. Chicago: Rand McNally. Eyestone, Robert. 1978. From Social Issues to Public Policy. New York: Wiley. Gormley, William. 1983. The Politics of Public Utility Regulation. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. Hardin, Garrett. 1968. "The Tragedy of the Commons." Science 162: 1243-48. Heintz, H. Theodore, and Hank Jenkins-Smith. 1988. "Advocacy Coalitions and the Practice of Policy Analysis." Policy Sciences 21: 263-77. Jenkins-Smith, Hank. 1988. "Analytical Debates and Policy Learning: Analysis and Change in the Federal Bureaucracy." Policy Sciences 21: 169-211. Jenkins-Smith, Hank, and Gilbert St. Clair. 1993. "The Politics of Offshore Energy: Empirically Testing the Advocacy Coalition Framework." In Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith, eds., Policy Change and Learning.: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. Jenkins-Smith, Hank, and Paul Sabatier. 1993a. "The Study of Public Policy Processes." In Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith, eds., Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. 669 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly . 1993b. "The Dynamics of Policy-Oriented Learning." In Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith, eds., Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. Jones, Charles 0. 1977. An Introduction to the Study of Public Policy, 2d ed. Boston: Duxbury Kingdon, John. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston: Little Brown. Lam, Danny. 1994. "Institutions, Engineering, Infrastructure, and Performance in the Governance and Management of Irrigation Systems: The Case of Nepal." Unpublished dissertation, Indiana University. Lindblom, Charles E. 1968. The Policy-making Process. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Lowi, Theodore. 1964. "American Business, Public Policy and Political Theory." World Politics 16: 677-715. . 1972. "Four Systems of Policy, Politics, and Choice." Public Administration Review 32: 298-310. Macey, J. 1992. "Organizational Design and Political Control of Administrative Agencies." Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 8: 93-110. Mayhew, David. 1974. Congress: The Electoral Connection. New Haven: Yale University Press. McCubbins, Mathew, Roger Noll, and Barry Weingast. 1989. "Structure and Process, Politics and Policy: Administrative Arrangements and the Political Control of Agencies." Virginia Law Review 75: 431-82. Miller, Gary 1992. Managerial Dilemmas: The Political Economy of Hierarchy. New York: Cambridge University Press. Moe, Terry 1984. "The New Economics of Organization." AmericanJournal of Political Science 28: 739-77. . 1990a. "The Politics of Structural Choice: Toward a Theory of Public Bureaucracy." In Oliver Williamson, ed., Organization Theory: From Chester Barnard to the Present and Beyond. New York: Oxford University Press. . 1990b. "Political Institutions: The Neglected Side of the Story." Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 6: 213-53. Moe, Terry, and Scott Wilson. 1994. "Presidents and the Politics of Structure." Law and Contemporary Problems 57: 1-44. Niskanen, William 1971. Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Chicago: Aldine. Olson, Macur. 1965. The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons. New York: Cambridge University Press. 670 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Comparison of Three Emerging Theories of the Policy Process . 199 la. "A Framework for Institutional Analysis." Working paper 91-14. Bloomington, IN: Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. . 1991b. "Rational Choice Theory and Institutional Analysis: Toward Complementarity." American Political Science Review 85: 237-43. Ostrom, Elinor, Roy Gardner, andJames Walker. 1994. Rules, Games, and Common-pool Resources. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Rosenthal, Alan. 1993. The Third House: Lobbyists and Lobbying in the States. Washington, DC: CQ Press. Sabatier, Paul. 1988. "An Advocacy Coalition Framework of Policy Change and the Role of Policy-Oriented Learning Therein." Policy Sciences 21: 129-68. . 1991. "Toward Better Theories of the Policy Process." PS: Political Science and Politics 24: 147-56. . 1993. "Policy Change Over a Decade or More." In Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith, eds., Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coali- tion Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. Sabatier, Paul, and Ann Brasher. 1993. "From Vague Consensus to Clearly Differentiated Coalitions: Environmental Policy at Lake Tahoe, 19641985." In Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith, eds., Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. Sabatier, Paul, and Hank Jenkins-Smith, eds. 1993a. Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalitions Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. . 1993b. "The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Assessment, Revisions, and Implications for Scholars and Practitioners." In Paul Sabatier and Hank Jenkins-Smith, eds., Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. Salisbury, Robert. 1986. "Washington Lobbyists: A Collective Portrait." In Allan Cigler and Burdett Loomis, eds., Interest Group Politics, pp. 146-61. Wash- ington, DC: CQ Press. Schlager, Edella. 1990. "Model Specification and Policy Analysis: The Case of Coastal Fisheries." Unpublished dissertation, Indiana University. . 1995. "Policy Making and Collective Action: Defining Coalitions Within the Advocacy Coalition Framework." Policy Sciences 28: 243-70. Schneider, Mark, and Paul Teske, with Michael Mintrom. 1995. Public Entrepreneurs: Agents for Change in American Government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Sharkensky, Ira. 1968. Spending in the American States. Chicago: Rand McNally. Simon, Herbert. 1985. "Human Nature in Politics: The Dialogue of Psychology with Political Science." American Political Science Review 79: 293-304. 671 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Political Research Quarterly Tang, S. Y. 1992. Institutions and Collective Action: Self-Governance in Irrigation. San Francisco: ICS Press. Welch, W P 1983. "The Political Feasibility of Full Ownership Property Rights: The Cases of Pollution and Fisheries." Policy Sciences 16: 165-80. Wilson, James Q. 1980. The Politics of Regulation. New York: Basic Books. Wood, B. Dan, and Richard Waterman. 1991. "The Dynamics of Political Control of Bureaucracy" American Political Science Review 85: 801-28. Received: September 16, 1995 Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 3 (September 1996): pp. 651-672 672 This content downloaded from 197.220.196.195 on Sat, 24 Nov 2018 10:25:28 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms