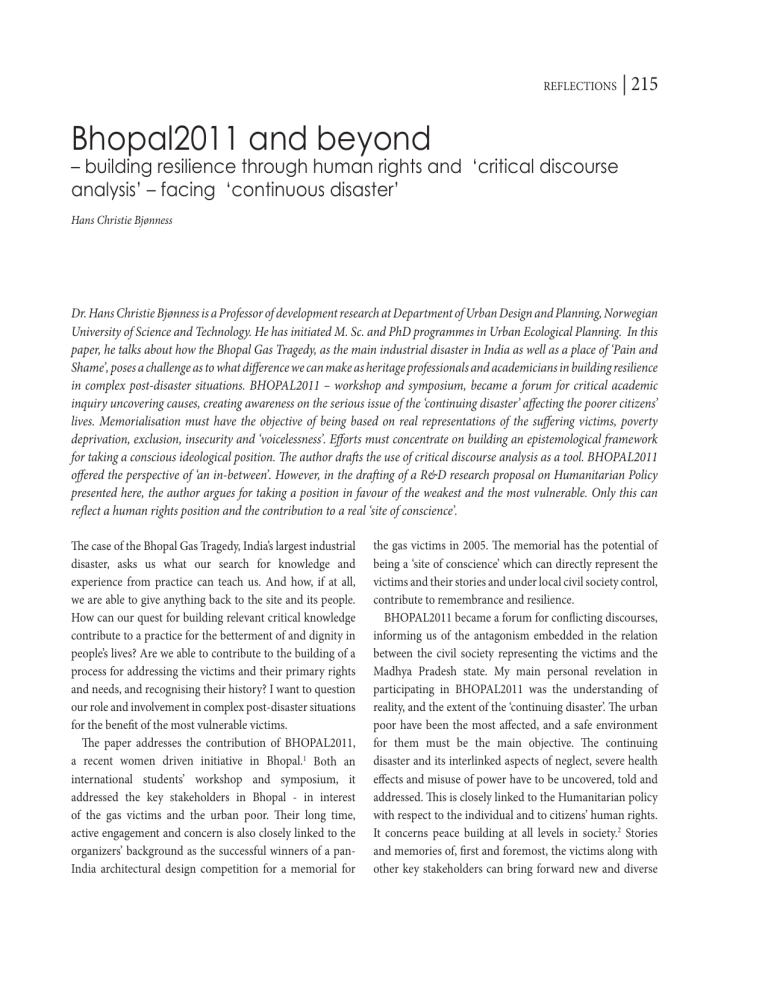

REFLECTIONS | 215 Bhopal2011 and beyond – building resilience through human rights and ‘critical discourse analysis’ – facing ‘continuous disaster’ Hans Christie Bjønness Dr. Hans Christie Bjønness is a Professor of development research at Department of Urban Design and Planning, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. He has initiated M. Sc. and PhD programmes in Urban Ecological Planning. In this paper, he talks about how the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, as the main industrial disaster in India as well as a place of ‘Pain and Shame’, poses a challenge as to what difference we can make as heritage professionals and academicians in building resilience in complex post-disaster situations. BHOPAL2011 – workshop and symposium, became a forum for critical academic inquiry uncovering causes, creating awareness on the serious issue of the ‘continuing disaster’ affecting the poorer citizens’ lives. Memorialisation must have the objective of being based on real representations of the suffering victims, poverty deprivation, exclusion, insecurity and ‘voicelessness’. Efforts must concentrate on building an epistemological framework for taking a conscious ideological position. The author drafts the use of critical discourse analysis as a tool. BHOPAL2011 offered the perspective of ‘an in-between’. However, in the drafting of a R&D research proposal on Humanitarian Policy presented here, the author argues for taking a position in favour of the weakest and the most vulnerable. Only this can reflect a human rights position and the contribution to a real ‘site of conscience’. The case of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy, India’s largest industrial disaster, asks us what our search for knowledge and experience from practice can teach us. And how, if at all, we are able to give anything back to the site and its people. How can our quest for building relevant critical knowledge contribute to a practice for the betterment of and dignity in people’s lives? Are we able to contribute to the building of a process for addressing the victims and their primary rights and needs, and recognising their history? I want to question our role and involvement in complex post-disaster situations for the benefit of the most vulnerable victims. The paper addresses the contribution of BHOPAL2011, a recent women driven initiative in Bhopal.1 Both an international students’ workshop and symposium, it addressed the key stakeholders in Bhopal - in interest of the gas victims and the urban poor. Their long time, active engagement and concern is also closely linked to the organizers’ background as the successful winners of a panIndia architectural design competition for a memorial for the gas victims in 2005. The memorial has the potential of being a ‘site of conscience’ which can directly represent the victims and their stories and under local civil society control, contribute to remembrance and resilience. BHOPAL2011 became a forum for conflicting discourses, informing us of the antagonism embedded in the relation between the civil society representing the victims and the Madhya Pradesh state. My main personal revelation in participating in BHOPAL2011 was the understanding of reality, and the extent of the ‘continuing disaster’. The urban poor have been the most affected, and a safe environment for them must be the main objective. The continuing disaster and its interlinked aspects of neglect, severe health effects and misuse of power have to be uncovered, told and addressed. This is closely linked to the Humanitarian policy with respect to the individual and to citizens’ human rights. It concerns peace building at all levels in society.2 Stories and memories of, first and foremost, the victims along with other key stakeholders can bring forward new and diverse 216 | BHOPAL2011 perspectives contributing to contextual and analytical knowledge. In our respective positions, we need to question if our presence is contributing to the conflict or to mediation and resulting in action benefitting the primary stakeholder, the victims. Dealing with ‘places of pain and shame’ and with difficult heritage3 is possibly more relevant for our daily professional practice than what we think. First of all, it brings forward the misuse of power, serious violations of human rights and sometimes neglect of the civil society. It also embodies complex issues of national pride, nation building and identity. Nietzsche in his ‘On the uses and Disadvantages of History for life’ was early in highlighting the contested role of history in this respect.4 It also concerns, in Foucault’s perspective, our daily practice with the ‘real history’ and in building constitution and civil society according to Habermas in respect of universal human and cultural rights.5 UNESCO suggests: ‘Your Symposium may serve as an excellent opportunity to exchange experiences from the world over the role of cultural heritage as a democratic and community-building force.’6 The workshop also raised the issue that the site did not constitute ‘authorised heritage’ related to ‘authorised discourses’7, but conflicting heritage in context of ‘sites of pain and shame’8 related to contemporary history of the largest industrial disaster in India.9 The BHOPAL2011 workshop and symposium provided the opportunity for a sharing and learning exercise between the concerned students, faculty and the local, civil and government bodies.10 The active organisers followed this up with publishing and disseminating the outcome. The lessons from the case of Bhopal have the potential to inform theory and method in working with sites of such complexity, and this publication stands to be of great value. On Human and Cultural Rights For the gas victims in Bhopal and the civil society in affected areas, there exist dual perspectives linked to the past and the need to address the present. It can be said that we need to bring the past into the present – the gas tragedy must not be forgotten. The human rights issues of the past are not only about compensation, recognition of severe health effects and rehabilitation, but also about the victims’ rights to get their stories of suffering and neglect heard. It is about the need to recognise and address the ‘continuing disaster’ of groundwater contamination and unsafe upbringing environments along with rights to land and property securing their tenure ship, basic shelter needs and safe drinking water. Irene Khan makes a convincing case that ‘putting human rights at the centre of the effort to end poverty will help us achieve this goal’.11 Poverty is the denial of human rights through discrimination, state repression, corruption, insecurity and violence.12 In her pledge for a new human rights plan to address the poverty alleviation challenge, Irene Khan stresses on the necessary commitment to achieve results on the ground and states that the generally stated Millennium Development Goals (MDG) are unable to do that. Our main effort must be to bring forward the poor’s representation of their own reality. Manheim states that we are unable to represent the poor and that only the poor can represent themselves in efforts of development.13 The third point mentioned by Khan in the Human Rights Plan to address poverty talks of the need to ‘set targets that speak directly to the issues of power’. 14 Relationships between Human Rights and Cultural Rights are mainly discussed in terms of ‘Heritage and Identity’15 and in relation to cultural diversity.16 In this context, I want to bring forward the recent and relevant work of Farida Shaheed to the challenges of working with multiple heritages and with ‘heritage community’. Shaheed recommends in a report on cultural rights to UN Human Rights Council, that a community level dimension should be introduced when it comes to Cultural Rights and the right to access cultural heritage. She writes: “…from a human rights perspective, cultural heritage is also to be understood as resources that enable the cultural identification and development processes of individuals and communities”. In the context of human rights, cultural heritage entails taking into consideration the multiple heritages through which individuals and communities express their humanity, give meaning to their existence, and build their world views’ (my italics). And she provides ‘significance for particular individuals and communities, thereby emphasizing the human dimension of cultural heritage’.17 REFLECTIONS Reference is also given to the Faro Convention, which refers to the notion of ‘heritage community’, and consists of people who value specific aspects of cultural heritage which they wish, within the framework of public action, to sustain and transmit to future generation’.18 Shaheed comments on the societal developmental perspective: ‘This implies that concerned communities may reunite people from diverse cultural, religious, ethnic and linguistic backgrounds over a specific cultural heritage that they consider they have in common’.19 This is highly relevant in the case of Bhopal, where the objective of a memorial must also be to unite people over the common struggle for justice and resilience following the Bhopal gas tragedy. Across religious divides, mostly the urban poor and labourers, were the worst hit and continue to be the sufferers. Furthermore, the Bhopal gas tragedy indiscriminately hit across existing social divides and created new classification in the post-disaster vocabulary – the victims, the survivors, women, widows, disabled children, ‘paani peedit’ (Hindi for water affected), but what was common is that almost all were poor.20 Critical discourse theory towards memories Possibly, the most difficult challenge we face is in being able to bring forward the stories and memories that can have an impact on human and cultural rights’ implementation and mediation in Bhopal for the benefit of the victims. Thomas Brandt writes that one of the overarching research questions arising in relation to the planning of a memorial site and Union Carbide, Bhopal plant is simply: What stories could be told at a museum or a memorial site for the Bhopal gas tragedy? The ‘authorized heritage’ must not dominate. The local struggle towards resilience as well as the opposition of the national government must be understood from all parties’ recognition that ‘heritage becomes a political resource’ around which stakeholders ‘interests negotiate and play out political recognition and struggles for legitimacy’.21 (my italics). Smith stresses the importance searching for the main, and often underlying, root causes of the conflict at hand. The researcher’s role will be to bring forward real views representative of the discourses among the different stakeholders and at different levels in society. 22 | 217 The method of Critical Discourse Analysis is, therefore, central in addressing and bringing forward the victims and the urban poor’s legitimate rights, as well as building knowledge and representations which ‘frame shared perceptions of the past’ of the victims. In the following paragraphs I will illustrate this with quotes from the open discourse at BHOPAL2011, and move on to critical discourse analysis and its challenges in relation to the building of public memory. During the two week workshop and symposium, the participants were confronted with opposing views of the past, the present and future with respect to the nature of the disaster, responsibilities and on-site measures. The content and language used in the discourse exposed large gaps to be bridged between the acceptance of the consequences of the disaster by the two main parties - the state government and the civil society representing the gas victims. A Madhya Pradesh state representative characterised the situation in strong words: “It has been WAR here – literally speaking - between the government and the civil society. This has happened because a dialogue of reasonable character has not taken place. It is hard to take a discussion when someone abuses you. If it is by design or accident … Well, we have different ways of addressing it”.23 This is in stark contrast to another statement by a journalist and civil society activist: “The immediate tragedy was followed by another – 26 years of painful struggle on the streets, courts, college campuses and corporate boardrooms. But there is a crucial difference in the two tragedies. The gas leak rendered them passive victims. The sustained struggle gave them agency and restored power. Any commemorative project at the site must give the right to the survivors to construct their identity”.24 New normative perspectives have been brought into the situation regarding the Right to Information Act by the Government of India and the legal proceedings in Bhopal in 2010. In the context of the Bhopal gas tragedy, it is important to bring forward discourses at different time periods right from the start up of the Union Carbide in the 60s up till now. This should be brought forward in terms of the public memory at the time, possibly through interviews with living representatives.25 James Jasinski defines public memory as “a body of beliefs and ideas that help the public and society understand its past, present and by implication, its future”.26 218 | BHOPAL2011 The contextual situation is always at the centre, but opens to diverse interpretations.27 Conducting memory studies, especially targeting witness testimonies, also transmits responsibilities. Ross Poole comments, ‘In so far collective memory has a cognitive aspect, it makes claims about the past. These may be confirmed or disconfirmed by historical research. This does not mean that collective memory is just bad history. It is more like history written in first person, and its role is to inform the present generation of its responsibilities to the past’28 – and I would add the present and future. This is also a reminder to the educator and researcher that bringing forward witnesses memories commits us as professionals. We will become involved and must also take responsibility in terms of the pledges of the victims in support of their human rights. The Bhopal Union Carbide disaster has possibly given poverty an identity in India and internationally and has exposed the vulnerability of the urban poor, in particular women and children in critical disaster situations. Furthermore, Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer mention, the second interpretive use of witness testimony to be the development of ‘cosmopolitan ‘or transnational memory cultures able to sustain efforts towards global attainment of human rights’.29 Hopefully, the Bhopal Gas Tragedy also has this effect in India and internationally to impart the necessity of corporate and state responsibility in terms of practice of human rights’ principles on the ground. We must, with respect and care, enter into the past. I would quote Dipesh Chakrabarty from his book on memories of Partition in India in 1947, ‘Habitations of Modernity’: “…what people do not even wish to remember, the forgetting that comes to our aid in dealing with pain and unpleasantness in life. Memory, then, is far more complicated to the investigator-historian who approaches the past with one injunction: ‘Tell me all’”30 Teun Van Dijk reminds us that it is necessary, in addition to personal and group knowledge, to build cultural knowledge for implementing critical discourse analysis (CDA). He writes ‘Discourses are like icebergs of which only some specific forms of (contextually relevant) knowledge are expressed, but of which a vast part of presupposed knowledge is part of the shared socio-cultural common ground’.31 This is also stressed by Ruth Wodak in a critical discourse-historical approach: ‘In investigating historical, organisational and political topics and texts, the discoursehistorical approach attempts to integrate a large quantity of available knowledge about historical sources and the background of the social and political fields in which discursive ‘events’ are embedded’32. Jan Nederveen Pierse (2004) writes that discourse analysis in development ”means a step beyond treating development as ideology, or interest articulation, because it involves meticulous attention to development text and utterances, not merely as ideology but as epistemology”33 (my italics). The use of discourse analysis in critical education and research and development (R&D) efforts is essential in post disaster inquiries. But we have to be careful to focus on the fascination of making our inquiry into only narratives of representations of social and cultural realities. Our concern must be that discourse matters in bringing forward different stakeholders’ understanding, based on their experiences and class and thereby articulates the understanding of different positions, as suggested by Foucault, of both ‘insiders’ and us as ‘outsiders’. In the words of Habermas, this is necessary in a dialogue in civil society to work towards a shared understanding, not necessarily without internal conflicts in the understanding of realities and representations; but which can contribute to resilience for the victims and bring its civil society and citizens their due rights, without antagonising the government. A call for humanitarian policy in development and cultural continuity in Bhopal A sustained recovery for the urban poor victims and an address of the continuing disaster are interlinked and form the prime areas of the research proposal titled Bhopal 2012 – 2015 Humanitarian Policy, Planning and Practice. Postdisaster recovery tends to focus on the immediate aftermath of the disaster, and few studies look into long term recovery and accumulated knowledge. It requires understanding causes of changing livelihoods, in relation to embedded knowledge in the society – both in terms of indigenous knowledge and acquired knowledge, and in relation to local potential for disasters and measures for disaster risk REFLECTIONS reduction.34 When addressing the objective of building livelihoods, it is first needed to understand the diverse bundle of entitlements poor households command.35 This is closely linked to Amartya Sen’s works on ‘deprivational poverty and freedoms’,36 his last work on the ‘Idea of Justice’37 and an understanding of ‘critical literacy’ among the poor.38 This forms the starting point for a more comprehensive survey of social, human and cultural capital, together with physical and economical capital or assets. Social capital is also interpreted in its vertical dimensions which could imply hierarchical relationships and an unequal power distribution among its members and the government.39 It is recognised that place relations of the poor are essential for their survival through the critical networks they have built.40 Evictions, as well as most resettlement, are socially disruptive and have often severe gender selective effects on the less mobile part of the household, the women and children.41 The first objective in the research is to understand the stakeholder environment where their interests and contribution will be assessed.42 The first two research objectives related to humanitarian policy, process and practice are: (i) To contribute to livelihood entitlements and coping strategies; and the building community resilience for the affected community, and (ii) To determine the territorial and spatial relations between community based stakeholders and government networks related to disaster mitigation; and to understand how they interact. The third research objective as part of humanitarian policy, process and practice addresses the memories of a painful past, the post disaster struggle and efforts to rebuild community: (iii) Bringing forward the relation of the cultural legacy of the painful past of the disaster and long term development initiatives in affected precincts. The last research objective is related to planning, practice and Risk Reduction Strategies in the future: (iv) To develop an area based approach for integrated urban risk reduction strategies, based on mapping the effects in the field of the Bhopal gas tragedy, its continuing disaster and community struggle and cooperation. The research area is challenging and relevant. It is challenging because it touches the core of ethical | 219 considerations of our professional practice in cases of emergency and crises and the consequent efforts in R&D. It is relevant because it concerns humanitarian policy and practice, which should form the core, both in post disaster action and in risk reduction related to the continuing disaster and future preventive action. The research objectives above are related. For planning practice, mapping into the spatial consequences of memory will provide insights for strategies that integrate socio-spatial and environmental justice into the disaster prevention and mitigation. Care has to be taken not to contribute to ‘exclusion in efforts of inclusion’ (personal communication Professor Ashok Kumar, SPA, Delhi). The research area significantly brings forward the need to see planning ideology and policy in relation to a well-informed, assessed and disseminated knowledge base, and a responsive and responsible action on the ground. Concluding remarks We must continuously question our role, and involvement in complex post disaster situations and how we contribute to making a difference in the practice of human rights for the benefit of the most vulnerable victims. Universities role will always be marginal but can contribute constructively with long term involvement with research and development efforts. The intention of the architects at Space Matters, New Delhi, to design for a centre of research along with the memorial centre, has the clear mandate to build relevant knowledge for the cause of the gas victims and constructive assistance, and also building capacity for future risk reduction. This must not be wishful thinking! The causes and the serious consequences of the Bhopal gas tragedy will continue to be discussed and should, by educators and researchers. They must be explicit on their affiliations and interests, as well as research focus. BHOPAL2011 created a constructive targeted forum. In the process of post disaster recovery, we must never forget our duty to contribute in building resilience through human rights and critical discourse analysis – and to address ‘continuous disaster’.43 Our knowledge is not neutral. With it, comes a necessary and continuous effort to contribute whatever little to critical ‘cosmopolitan or transnational memory cultures able to sustain efforts towards global attainment of human rights’. ▪ 234 | BHOPAL2011 Thakur, N. (2008). “Hampi world heritage site: Monuments, site or cultural landscape”. Landscape Journal, vol. 12, no. 5. New Delhi: School of Planning & Architecture UNESCO. 2008. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. <http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/> Varma, P. K. (1997). The Great Indian Middle Class. New Delhi: Penguin Ward, John (1995). “Cultural Heritage Site Monitoring: Towards a Periodic, Systematic, Comparative Approach”. In Momentum, vol. 4, no. 3, ICOMOS Canada <http://www.icomos.org/icomosca/bulletin/ vol4_no3_ward_e.html> Why do people not visit Bhopal? Western experiences with and perspectives towards sites with catastrophe heritage (p. 194-197) 1. Blume, G. (2010). “Die Leiden von Bhopal”. Die Zeit, 12 Aug. 2010, p. 25 2. Comprehensive studies on the inadequacy of justice (especially in respect with technological globalisation) and its relation to the insufficiency of science in the case of Bhopal are numerous; for a survey see Jasanoff, S. (2007). “Bhopal’s trials of knowledge and ignorance”. In Isis, 98 (2007), pp. 344-350 3. Schweer, H. (2009). “Die Chemische Fabrik Stoltzenberg in Hamburg von 1923 bis 1945”. In Wolfschmidt, G. (ed.). Hamburgs Geschichte einmal anders – Entwicklung der Naturwissenschaften, Medizin und Technik, Teil 2. Nordestedt: Books on demand 2009, pp. 149-150. 4. For a detailed historical reconstruction of the relations between Stoltzenberg and the German Reich military authorities see the evidence provided by Schweer, H. (2008). Die Chemische Fabrik Stoltzenberg bis zum Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges. Ein Überblick über die Zeit von 1923 bis 1945 unter Einbeziehung des historischen Umfeldes mit einem Ausblick auf die Entwicklung nach 1945. Diepholz: GNT 2008 5. Op. Cit. Schweer (2009), pp. 151-152. 6. Phosgene is very volatile with a boiling point of 8°C. On wet surfaces, e.g. in the lungs, phosgene splits to hydrogen chloride, with delayed but even fatal physiological consequences for animals and humans. 7. Lütje, A. & Wohlleben, T. (1990). “Chemiefabrik Stoltzenberg – Zwei Katastrophen ohne Schuldige?” In Andersen, A. (ed.). Umweltgeschichte: Das Beispiel Hamburg. Hamburg: Ergebnisse-Verlag 1990, pp. 135136. 8. Op. cit. Schweer (2009), p. 156. 9. Ibid. Schweer (2009), p. 155. 10. Op. Cit. Lütje/Wohlleben (1990), p. 136. 11. Op. Cit. Schweer (2009), pp. 154-158. 12. Op. Cit. Lütje/Wohlleben (1990), p. 145. The official German permissions for the Techncische Pyrotechnik Klasse T1 are still accessible: BAM-PT1-0103 & BAMPT1-0104 (accessed 23 Jan. 2011). 13. Ibid. pp. 145-147. 14. Scholz, E.-G. (2004). “Stoltzenberg-Skandal – zuerst starb ein Kind”. Hamburger Abendblatt 7 September 2004 Bhopal2011 and beyond. Building resilience through human rights and ‘critical discourse analysis’ – facing ‘continuous disaster’ (p. 213217) 1. The full title: BHOPAL2011 Requiem and Revitalisation. 23rd of January – 4th of February 2011. The two initiators were Ms Moulshri Joshi and Ms Amritha Ballal of School of Planning & Architecture & Space Matters, Delhi. I am indeed thankful to the architects Ms Amritha Ballal and Ms Moulshri Joshi who invited me to join the struggle for financial and institutional support and for participating in the mind provoking and sharing exercise of BHOPAL2011. In October 2011, linked to the URBAN INDIA conference at NTNU, we met for a continuing joint effort on research application within ‘Humanitarian policy’. The BHOPAL2011 initiative with its workshop and symposium and publication and dissemination has been supported by the Research Council of APPENDICES Norway under its INDNOR research programme. 2. Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2009). Norway’s Humanitarian Policy. Report No. 40 (2008 -2009) to the Storting (Parliament). Oslo 3. Logan, William and Reeves, Keir (2009). “Places of Pain and Shame”. Dealing with difficult heritage. Series Key Issues in Cultural Heritage.Abingdon, Oxon (UK): Routledge 4. Nietzsche, Friedrich (1874). “Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen” (in German). “Untimely Meditations” (in English). Zweites Stück: Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben (in German). Second Part: On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life (in English). Berlin: C.G.Naumann (Original publication in German) 5. Flyvbjerg, Bent (1998). “Empowering Civil Society: Habermas, Foucault and the Question of Conflict”, in Douglas, Mike and Friedmann, John (1998). Cities for Citizens – Planning and the Rise of Civil Society in Global Age. Chichester, West Sussex (UK): John Wiley and sons 6. Letter written by Armorogum Parsuramen, UNESCO Representative for India to the Organising Committee of Bhopal2011. 7. Smith, Laurajane (2007). “Empty Gestures? Heritage and the Politics of Recognition” in Silverman, Helaine and Fairchild Ruggles, D (eds. 2007) Cultural Heritage and Human Rights. New York: Springer Science + Business Media 8. Op. Cit. Logan, William and Reeves, Keir (2009) 9. Laurajane Smith (2007) writes: ‘Embedded in the heritage management process are certain dominant or authorized discourses that both draw on and underpin the position of technologies of government. The naturalization of these discourses also facilitates the regulation of competing knowledge about the past and conceptualizations about the meaning of nature of heritage places and objects’ (ibid. page 163) (my italics) 10. Amritha Ballal (BHOPAL – emerging from the shadow of disaster. Not published abstract for presentation at the URBAN INDIA conference at the | 235 Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) October, 2011) brings forward the focus of the Bhopal2011 symposium and workshop within three issues, urban environmental conditions, memorialisation and dialogue with civil society. She sees ahead and suggests who the key stakeholders are: an emerging network of survivors groups, civil society, urban planners, architects, scholars, researchers and government officials. She proposes that they must together attempt to meet challenges of contemporary Bhopal. 11. Khan, Irene (2009). The Unheard Truth. Poverty and Human Rights. New York /London: W.W. Norton & Company. Quote of Kofi Annan in his foreword. 12. Khan, Irene (2011). “The Unheard Truth. Poverty and Human Rights”. On – tube http://www.youtube. com/watch?v=u5IHv_4cJ90 (Accessed 1 December 2011) 13. Manheim, K. (1949). Man and Society in an Age of Reconstruction. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World 14. Op.cit Khan, Irene (2009) 15. Graham, Brian and Howard, Peter (2008). The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity. Aldershot, Hampshire (UK): Ashgate Publishing Limited 16. Silverman, Helaine & Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2007). Cultural Heritage and Human Rights. New York. Springer Science + Business Media. Langfield, Michele, Logan, William & Crait, Máiréad Nic (2010). Cultural Diversity, Heritage, and Human Rights. Intersections in Theory and Practice. UK: Routhledge 17. Shaheed, Farida (2011). Report of an independent expert in the field of cultural rights. In Human Rights Council. “Promotion of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development”. Seventeenth Session. Published 21st March 2011. Geneva: UN General Assembly 18. Council of Europe (2005). “Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. The Faro Convention”. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. 236 | BHOPAL2011 19. Op.cit. Shaheed, Farida (2011) 20. We must never forget to ask what do a woman’s perspectives to human rights imply. (The Iranian Nobel Peace Prize laureate interviewed Shirin Ebadi interviewed by Nermeen Shaikh (2007) in The Present as History: Critical Perspectives on Global Power. New York: Colombia University Press. 21. Smith, Laurajane (2007). ibid page 159. 22. Brandt, Thomas (2011), Memo. Trondheim: NTNU 23. Statement made during the Bhopal2011 workshop 31 January 2011 24. Ms Rama Lakshmi, activist, journalist and museologist in her speech on “Processes through which Trauma and Social Movements are represented in Museum Space”. 4 February 2011. 25. Bjønness, Hans Christie (2011). “Building Memory of Heritage in multicultural Societies” in Tomaszewski, Andrzej & Giometti, Simone (eds. 2011). The Image of Heritage: Changing Perceptions, Permanent Responsibilities. Proceedings of International Conference of the ICOMOS Committee for Theory and Philosophy, March 2009, Firence: Edizioni Polistampa 26. Op. cit., Jasinski, (2001). “Sourcebook on Rethoric. Key Concepts on Contemporary Rhetoric Studies”. London/Delhi: Sage Publications. p.336. 27. Jovchelovitch, Sandra (2007). Knowledge in Context. Representations, Community and Culture. London and New York: Routledge 28. Poole, Ross (2008). “Memory, history and the claims of the past”. Memory Studies 2008 1: 149, Sage Publications 29. Hirsch, Marianne & Spitzer, Leo (2009). “The witness in the archive: Holocaust Studies”. Memory Studies 2009 2: 151, Sage Publications 30. Chakrabarty, Dipesh (2002). “Habitations of Modernity”. Essays in the wake of subaltern studies. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p.115 31. Van Dijk, Teun (2001). “Multidisciplianary CDA: a plea for diversity” in Wodak, Ruth & Meyer, Michael (2001). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London. Sage publications. page 114 32. Wodak, Ruth (2001). “The discourse – historical approach”. Ibid. Meyer (2001) 33. Pierse, Jan Nederveen (2004). Development Theory. Deconstructions/Reconstructions. London: Sage Publications 34. Sillitoe, Paul; Bicker, Alan and Pottier, Johan (2002). Participating in Development. Approaches to Indigenous Knowledge. London and New York. Routledge and Jigyasu, Rohit (2011), “Socio-economic recovery”. Unpublished article. 35. Griffin, Keith (1981) “The Poverty Trap”. Guardian, 25 October 1981 reviewing Sen, Amartya (1981). Poverty and Famines. An Essay on Entitlements and Deprivation. UK: Oxford Universtiy Press. Rakodi, Carol (2002). “A Livelihood Approach: Conceptual issues and Definitions” in Rakodi, Carol & LloydJones, Tony (2002). Urban Livelihoods. London, Eartscan 36. Sen, Amartya (1999). Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press 37. Sen, Amartya (2009). The Idea of Justice. London: Allen Lane of Penguin Books 38. Freire, Paulo (1972). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Middlesex, UK: Penguin Books Ltd 39. Groothert, Christian (1998). “Social capital”. The Missing Link. The World Bank. Social Development Family. Environment and Socielly Sustainable Network. Social capital Initiative. Working Paper no. 3. 40. Hamdi, Nabeel (2010). The Placemakers Guide to Building Community. London: Earthscan 41. Ballal, Amritha (2011a). “The spatial dimensions of urban homelessness. Nizamuddin basti, Delhi.” Master of Science in Urban Ecological Planning. Department of Urban design and Planning, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim 42. Samset, Knut (1996). The Logical Framework Approach. Oslo: Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation 43. The ‘continuous disaster’ and the urban dimension have been elaborated in Bjønness, Hans C. (2012) “Post Disaster Struggle. Towards socially responsible APPENDICES urban conservation and development. The case of Bhopal Gas Tragedy” in Proceedings of Int. conference of ICOMOS Committee for the Theory and Philosophy of Conservation and Restoration, Firenze, March 2011 (Published in April 2012) Post Bhopal2011(p. 221-224) 1. Moulshri Joshi cited by Rama Lakshmi. Washington Post Foreign Service, 9 July 2010. <http:// www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/ article/2010/07/09/AR2010070903209.html> accessed 28 May 2012. 2. Smith, Laurajane (2006). Uses of Heritage. Oxford: Routledge. 3. Sevcenko, Liz (2010). “Sites of Conscience: new approaches to conflicted memory”. Museum International. Vol. 62. No. 1. Pg. 24. UNESCO Publishing and Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 4. Ibid. Smith (2006), p. 3 5. Sevcenko, Liz (2008). “To Recall is to Learn”. Inter Press Service News Agency. <http://ipsnews.net/news. asp?idnews=42854> accessed 5 March 2010. Websites Wikipedia, The Bhopal Disaster http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhopal_disaster Bhopal Medical Appeal and Sambhavna Trust Clinic http://www.bhopal.org/ International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal http://www.bhopal.net/ Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief and Rehabilitation Department (Official Website of Government of Madhya Pradesh) http://www.mp.gov.in/bgtrrdmp/ Bhopal: 25 years on BBC News’ website on the Bhopal disaster http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/in_depth/business/2009/ bhopal/default.stm Students for Bhopal http://www.studentsforbhopal.org/ | 237 Books Amnesty International (2004). Clouds of Injustice. Bhopal Disaster 20 Years on Chouhan, T. R., Alvares, Claude, Jaising, Indira & Jayaraman, Nityanand (2004). Bhopal: The Inside Story Dembo, David, Wykle, Lucinda & Morehous, Ward (1990). Abuse of Power. Social Performance of Multinational Corporations: The Case of Union Carbide Doyle, Jack (2004). Trespass Against Us. Dow Chemical and The Toxic Century Eckerman, Ingrid (2005). The Bhopal Saga: Causes and Consequences of the World’s Largest Industrial Disaster Fortun, Kim (2001). Advocacy after Bhopal. Environmentalism, Disaster, New Global Orders Hanna, Bridget, Morehouse, Ward & Sarangi, Satinath (eds. 2005). The Bhopal Reader. Remembering Twenty Years of the World’s Worst Industrial Disaster Lapierre, Dominique (2004). Five past midnight in Bhopal Mukherjee, Suroopa (2010). Surviving Bhopal. Dancing Bodies, Written Texts, and Oral Testimonials of Women in the Wake of an Industrial Disaster Subramaniam, M. Arun & Morehouse, Ward (1986). The Bhopal Tragedy. What Really Happened and What it Means for American Workers and Communities at Risk Weir, Davied (1988). The Bhopal Syndrome. Pesticides, Environment, and Health