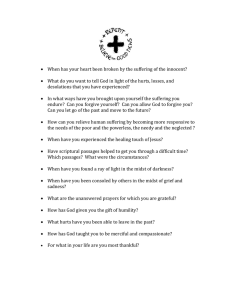

1 Sermon at Oriel college, Oxford, 27 January 2019 — Holocaust Memorial Sunday Job 40:1-14; 41:1-11 Dear friends, The story of Job can only be described as far-fetched. Job starts out as what we would call a pillar of society—in his time, of course, very long ago. He is rich, and lots of servants, day-workers, seasonal workers and occasional workers depend on him for their livelihood. He is wise, running his estate in an efficient way. And he is pious, trying to please God and to be fair to all his fellowhumans, not only his own clan. The Bible doesn’t say whether he was an Anglican, but there is no harm in thinking that he was. This man, unbeknownst to himself, becomes the object of a wager between God and his courtier, Satan. Satan in Job is like the “eye of the king” in the Persian empire mentioned in Herodotus and Xenophon (Torczyner). I quote from Wikipedia: “The Eye of the King was appointed by the Persian king to inform him of what was going on in the empire. Eyes supervised the payment of tribute, oversaw how rebellions were suppressed, and reported evils to the king.” Satan—God’s eye—assures God that there is something fishy about Job, his subject. Job looks very devout, but his faith is superficial only. If any misfortune should befall him, Job would turn his back on God. God, for his part, is certain that Job’s piety is authentic. To find out who is right the two of them submit Job to a series of cruel accidents: he loses his fortune, his children all die, he falls ill with a horrible skin-disease… God easily wins the wager: Job doesn’t budge an inch from his piety: “shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil?” he says. The case seems closed—but we’re only in chapter 2 of a book that has 42 chapters. Indeed, in the process of proving the integrity of Job, God has created a new problem. Bringing all those catastrophic events upon his servant just to test his loyalty was not politically astute. Of course, Job doesn’t know what happened in heaven. But prodded by his friends, who try to make him admit that he somehow deserved his misfortune—no doubt he has sinned in secret, they suggest—Job eventually figures it out for himself: what has happened to him is simply unfair. Job is happy to be patient, but if pressed he cannot accept responsibility for his misfortune. It must be God’s fault. 2 In his former life, Job thought the universe made sense. But in light of his recent experience, he now observes that he is not alone: lots of things are going on that do not seem to agree with the notion of a just and benevolent deity. What happens next, the crux of the book, is told in chapters 38, 39, 40 and 41. We read an extract from those chapters this evening. God answers Job from the whirlwind. God’s speeches are magnificent, as one would expect—God is a powerful speaker—but they are also enigmatic. The Hebrew is difficult. And the logic is hard to grasp. One cannot escape the impression that God in a way is skirting the issue. God never once mentions human suffering. But he gives a very long description of the crocodile. Today we observe Holocaust Memorial Sunday. A European State developed a political programme to annihilate all Jews living within its borders. This wasn’t new. Eventually—and this was new—six million Jews were killed. The injustice and the suffering still cry to high heaven. The wounds can never be healed. Especially because in our days again antisemitism is on the rise, in Europe, in the US, and also, although we may not like to hear it, in the United Kingdom. On this memorial Sunday I would like to propose a somewhat daring interpretation of God’s reply to Job. In this reply there is no answer to Job’s question, but there is something else: a suggestion that God suffers with humanity. More than what God says, the fact itself that God responds seems relevant. Although God does not give an explanation for human suffering, he does turn up. He shows concern. In fact, and this is the daring part of my interpretation: it almost seems as if God’s speech is bit rambling. God is taken aback, profoundly disturbed by Job’s words and the situation in which they are spoken. It is a constant characteristic of the biblical God to be touched by human suffering. “The LORD, the LORD God, merciful and gracious” is the name proclaimed to Moses when he demands to see God after the sin of the golden calf. The idea is not that God sits on a high throne pitying abject human beings. In story after story we observe that God is really moved by whatever happens to his creatures. More than that. God is drawn into the life of human beings: in Job he makes a special appearance to respond to Job’s claims. In the book of Ezekiel, God leaves the Temple of Jerusalem and goes into exile, just like his people. The magnificence of God’s throne-chariot, described in Ezekiel 1, and the magnificence of God’s speeches in Job 38-41 cannot hide the underlying poverty: when Israel goes into exile, the Lord loses his earthly dwelling place; and 3 when Job formulates his questions on the suffering of the innocent, God doesn’t really have an answer. It is not just compassion. The God of the Bible is an only God. He has no one to interact with except humans. He has some apparatchiks in his court, like Satan, who comes and tells God what he already knew; or like the angels: God says, “Go and say such and such a thing,” and the angel goes. But this is not what God is after. The real partners of God are human beings. Created in God’s image they are able to interact with him; to praise him, to call upon his help, to broach challenging theological questions. In this constellation—a unique God faced with only humans— human suffering cannot happen without God suffering too. A well-known story in Genesis resembles the story of Job in many respects. God puts a righteous man to the test to see if his piety is genuine. He tells Abraham: Go offer up your son on the mountain I will show you. In Job, the idea of the test comes from Satan, thus at least initially exculpating God. But in Genesis 22, it is God who designs the test and carries it out. Abraham passes the test with flying colours, so much so that it is unnecessary to see it through to the end. An angel calls Abraham back and everything ends well, except for three days of dread and confusion (explored in Shalom Spiegel’s The Last Trial). In this story, the suffering of God is not located in the response he is called upon to give. Abraham doesn’t call God to account. In this story, divine suffering is situated, if anywhere, at the very beginning. God has promised Abraham a son, and this son has now been born, as told in the preceding chapter. Will Abraham still walk with God? Will he still go were God calls him to go? Are they still partners? God’s uncertainty pushes him to put Abraham to the test. The biblical motif of divine suffering is meant to give us hope. “Trouble shared is trouble halved,” they say. In our pain and desperation we are not alone: the entire universe awaits redemption with the children of God; and not only the universe, the Maker too is involved. In all our affliction he is afflicted. It may seem odd, on Holocaust Memorial Sunday, to preach a message of hope. Is it not disrespectful of the victims, for whom, on the face of it, there was no hope? But preaching is not something that should be channeled by decorum. We preach from a text. Preaching is rather similar to singing from a sheet. Of course the choir this evening is not narrowly following the sheet: you have internalized the notes, the melody, the extraordinary force of the music. You, and your director/David, are interpreting. But ultimately, what you bring to us in this service does not come 4 from you. It comes from the sheet, from the composer; from the muse… So it is with preaching: the message of hope is in the sheet. The preacher draws the sermon from the biblical text, from the dramatic human experiences that are condensed in it, from the spirit. In the Saint Ludger Church in Münster, Germany, there is a wooden image of Jesus on the Cross. The image was carved by Heinrich Bäumer in 1929 and hung on the West side of the Church. In 1944 the church was destroyed when the city was bombed. After the war, the image was found under the rubble: it had lost both its arms. It was not repaired, but hung back on the reconstructed church wall—a Christ without arms—with the inscription: „ICH HABE KEINE ANDEREN HAENDE ALS DIE EUEREN“—I have no other hands than yours.