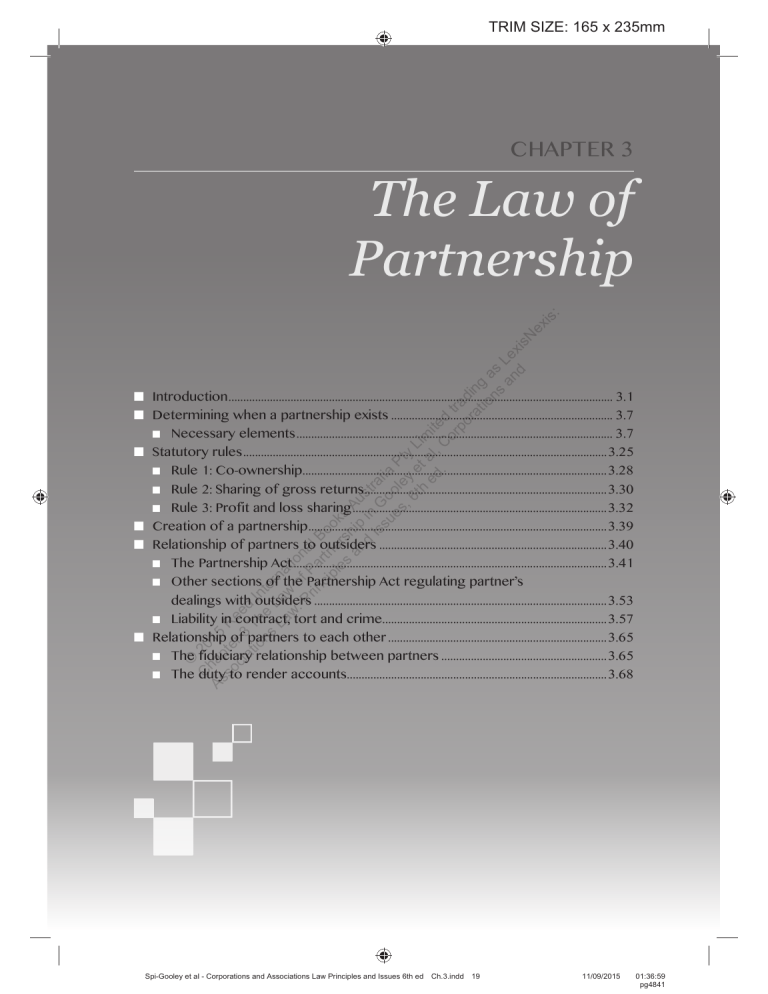

Gooley's - chpt 3 Partnership Law, Corporations and Associations Law Principles and Issues 6th ed Ch03 waterma

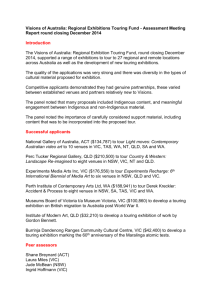

advertisement