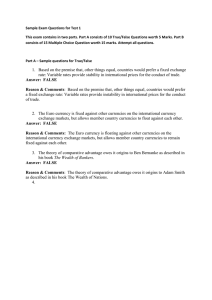

EC2010: Money and Banking Final Examination, 2010-11 Time: Two Hours The exam consists of three parts. Each part is compulsory and carries equal weight. The total marks for the exam add up to 300. Each part counts for 100 marks. Part I (100 marks): Give short answers to all four questions. 1) What do you understand by the term ‘moral hazard’? (25 marks) A: The concept of asymmetric information (AI), which treats the problem of 2 parties to a transaction not having the same information about it, has two sub-concepts or instances. Firstly, AI operates before a transaction to create adverse selection, for example, in the case of finance, that the riskier borrowers enter the market first. (Students may refer to the well-known example of Akerlof’s ‘lemons’ illustration concerning second hand cars in an auction.) Secondly, AI operates after a transaction to create moral hazard, meaning in a financial example that a borrower uses the money borrowed for purposes or in ways not contemplated by and not visible to the lender. In both cases the risk to the lender is increased. A specific dimension of moral hazard concerns the perverse incentives it can engender on the part of managers, known as the principalagent problem. 2) Using simple examples, what is meant by ‘debt’ and ‘equity’? (25 marks) A: A balance sheet has two sides, assets and liabilities, that equal one another (A=L). Liabilities, however, comprise two main types, debt and equity (A=D+E), often written as A=L+E, although this is not strictly true. While equities are certainly assets on the accounts of their owners, on the balance sheet of their issuers they are liabilities. Debt covers loans and bonds, that is, funds lent to the business, comprising, albeit in different combinations, a principal amount and an agreed revenue (interest) due to the lender regardless of its profitability but not conferring ownership of the borrowing entity on the lender. Equity, also known as ‘own capital’, refers to the shares in a company. These do confer ownership on shareholders, but they are also ‘below the line’, meaning they are treated in toto as ‘residual value’ which is only released to shareholders after profitability and then only when the directors deem it prudent to release cash. 3) Regarding central banking, what is the difference between operational and goal independence? (25 marks) A: Independence refers to the central bank’s independence in (a) setting its goals and (b) achieving them. In the clearest example, a goal might be n% inflation; achieving that goal could be a matter of setting interest rates through a monetary policy committee. The arguments for and against central bank independence turn on whether or not (or to what extent) economic governance should be free of political interference. If there is not to be a ‘democratic deficit’, to whom does a central bank governor report and is that accountability meaningful? Generally, central bank independence is understood to mean operational or instrumental independence, meaning the central bank is left free to set interest rates in the context of a given inflation target, say 2%, this being in most people’s mind synonymous with price stability. A long literature dating back to Henry Thornton in 1802 discusses this topic. Nowadays, the central banks of most democratic countries are independent in the narrower sense. 4) Explain ‘price stability’ and identify two advantages of it. (25 marks) A: Price stability refers to a constant low increase in the aggregate price level. Not zero, but gently incremental to allow growth. It is measured in terms of the rate of inflation, but it is achieved in the main by controlling the money supply, a nominal anchor that helps guard against time inconsistency in monetary policy because it’s eye is kept on the longer run, thus countering the short term fluctuations often associated with political interference and its ‘cousin’, discretionary policy. Two advantages of price stability are (1) it reduces uncertainty regarding the financial future which is crucial for income, investment and general economic planning for business, government and individuals alike, and (2) in its wake comes social stability because other important considerations follow on such as the employment level, growth, and stability in financial markets and foreign exchange markets. The, largely now achieved, general perception of price stability as a public good is crucial to the concept’s acceptance by the population as a whole. Part II (100 marks): Answer one of the following two questions. (The remaining answers are given in essence because I assume students will give more amplified answers. The point of these questions is to give the student the opportunity to (a) reiterate ‘bare bones’ knowledge about how the financial system is understood and conducted, but also (b) to show an understanding of the logic of modern finance, why it is conceived and operated the way it is.) 5) A financial centre depends on the depth and breadth of its liquidity. Describe (i) why this is so, (ii) how it is achieved and maintained. A: A financial centre depends for its business on the money passing in and out of it, whether short term, as in money markets, or longer term as in capital markets. If money is to enter, it has to be able to leave easily. For this to happen, assets held need to be readily turned into cash, capable of becoming liquid. This is affected by many things – the type, range and accessibility of markets, intermediaries and instruments and of investments being best priced, so that there are always people willing to lend. They have also to be able to freely on-sell their assets to other parties so that they can exit at will and without hindrance. Depth of liquidity refers not only to the amount of money but to the importance of respect for property rights, the rule of law, and other attributes of a modern democracy, such that one can be sure there will be no sequestrating, confiscating or plundering of assets, for example. It also assumes that central bank independence is operating and that a government’s fiscal objectives and/or party-political goals do not perturb or contradict economic fundamentals. Breadth of liquidity means being open to as many players as possible, for which reason the lighter the regulation the better. Hence, for example, ‘Big Bang’ in mid 1980s London, intended to create off-shore status on-shore and to protect London as a global financial centre in a world that was rapidly becoming not only global but also virtual. Deregulation of this kind often means excusing financial centres of any more highly regulated contexts (concerning exchange controls or taxation, for example) that might otherwise exist in order that they may be able to compete on a global level. On the other hand, to ensure that banks do not take excessive risks, governments seek to regulate in terms of restrictions on entry, disclosure, capital adequacy, etc. 6) Why is it in the interests of a bank’s shareholders that some of the bank’s reserves are held in short term instruments? A: A bank’s shareholders, like all shareholders, are profit seeking and profit maximising, and thus seek to maximise their return to capital. In that sense they would not normally allow funds to lie fallow, but there is a trade-off to be considered between the role of a capital cushion in safeguarding the bank’s overall operations and the reduced direct overall return on invested capital this implies. In non-buoyant or uncertain times, the capital cushion may be preferred because one takes the longer view. But in buoyant times the bank’s profitability is enhanced the more it can, with safety, invest its funds in such things as money market deposit accounts, which escape the net of reserve requirements and thus being included in the money supply. Part III (100 marks): Answer one of the following two questions. 7) Giving examples from the 20th century, describe the main exchange rate regimes, then say which is best suited to today’s conditions. A: The main examples of exchange rate regimes are fixed, floating (flexible) and managed float. They can be characterised as follows: Fixed – a currency is pegged to another currency whose value is assumed to be immutable. Floating – where all currencies float against all other currencies. Managed float – where governments make foreign exchange interventions in order to achieve a specific exchange rate rather than that given by the markets. To keep the parity of a currency fixed the central bank makes FX interventions, e.g. buying its currency (selling FX) when its currency is over-valued so as to effect interest rates, this the perceived value of its currency relative to others, thus its exchange rate. Examples of the first, fixed, are easily identified. The gold standard with an assayed amount of gold at its centre or base, the Bretton Woods system based on the goldexchange standard where 35$ were equivalent to 1 oz of gold. The euro is also a fixed exchange rate system internally, even though it floats against other currencies. Floating exchange rates represent something of a theorem, even a utopia, since the idea presupposes all currencies float against all others, so that market forces universally operate and there is no government intervention. In practice, many of not most governments intervene, if only to protect their economies from adverse payment balances, unaffordable exports and so on. Arguably, if fixed exchange rates are a thing of the past (even the euro floats against the rest of the world), and if universally floating rates are utopian, there is little choice but to opt for managed or ‘dirty’ floating (floating when it suits you or is possible). Exceptions would be political regimes that have no truck with western democracy and countries that either use a currency board to hook onto someone else’s ‘sound’ currency, or adopt entirely the sound currency of another country (so-called dollarisation). 8) The supply of bonds shifts for three main reasons: i) expected investment profitability ii) inflation expectations iii) governmental budgets Discuss and depict (ii), known as the Fisher Effect. A: In the case of expected changes in inflation, because bond prices are negatively related to interest rates, the argument runs that for a given interest rate and a given bond price, when expected inflation increases/falls the real cost of borrowing falls/rises. Hence the quantity of bonds supplied increases/decreases. If the expected rate rises to 10% the expected return on bonds falls, so demand for bonds falls and the demand curve shifts to the left, while the supply curve shifts to the right. In short, when there is an expected rise in inflation interest rates will also rise. This is known as the Fisher Effect, after Irving Fisher, the American economist who first described it. (Illustration required.)