Bipolar Disorder: Symptoms, Types, Prevalence & Comorbidity

advertisement

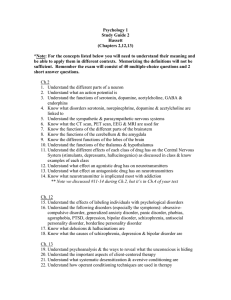

BY: JAMIELYN MANGUBAT BIPOLAR AND RELATED DISORDERS BIPOLAR DISORDERS The key identifying feature of bipolar disorders is the tendency of manic episodes to alternate with major depressive episodes in an unending rollercoaster ride from the peaks of elation to the depths of despair MAJOR DEPRESSIVE HYPOMANIA MANIA MANIC EPISODE A DISTINCT PERIOD ABNORMALLY OF & PERSISTENTLY ELEVATED, EXPANSIVE OR IRRITABLE MOOD AND ABNORMALLY & PERSISTENTLY INCREASED GOAL-DIRECTED ACTIVITY OR ENERGY NEARLY EVERY DAY. MAJOR DEPRESSIVE EPISODE 5 (OR MORE) OF THE SYMPTOMS IS PRESENT NEARLY DURING THE EVERYDAY SAME 2 – WEEK PERIOD AND REPRESENT A CHANGE FROM THE PREVIOUS FUNCTIONING; AT LEAST ONE OF THE SYMPTOMS IS EITHER (1) DEPRESSED MOOD LOSS OF PLEASURE INTEREST OR (2) OR SYMPTOMS ARE THE SAME SYMPTOMS ARE THE SAME AT LEAST 4 DAYS AT LEAST 1 WEEK NOTICEABLE BUT NOT SEVERE ENOUGH TO IMPAIR FUNCTIONING OR REQUIRE HOSPITALIZATION INTERFERES SOCIAL OR OCCUPATIONAL FUNCTIONING OR REQUIRES HOSPITALIZATION TO PREVENT HARM BIPOLAR I BIPOLAR II DISORDER DISORDER DIAGNOSED WITH MANIC EPISODE HYPOMANIC EPISODE AND MAJOR DEPRESSIVE EPISODE DIAGNOSED WITH HYPOMANIC EPISODE AND MAJOR DEPRESSIVE EPISODE CYCLOTHYMIC DISORDER DIAGNOSED WITH 2-YEAR PERIOD OF HYPOMANIC & MAJOR DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS BUT DO NOT MEET THE CRITERIA SUBSTANCE/MEDICATIONINDUCED BIPOLAR AND RELATED DISORDER • A prominent and persistent disturbance in mood that predominates in the clinical picture and is characterized by elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, with or without depressed mood, or markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities. • The symptoms developed during or soon after substance intoxication or withdrawal or after exposure to a medication. • The involved substance/medication is capable of producing the symptoms. BIPOLAR AND RELATED DISORDER DUE TO ANOTHER MEDICAL CONDITION • A prominent and persistent period of abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and abnormally increased activity or energy that predominates in the clinical picture • There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is the direct pathophysiological consequence of another medical condition • The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, or necessitates hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others, or there are psychotic features. PREVALENCE • There is some similarity in the lifetime prevalence rates for bipolar spectrum disorders across many different countries ranging from India and Japan to the United States, Lebanon, and New Zealand (0.1 to 4.4 percent; Merikangas et al., 2011). • Bipolar disorder seems to occur at about the same rate (1%) in childhood and adolescence as in adults (Brent & Birmaher, 2009; Kessler et al., 2012; Merikangas & Pato, 2009). • Bipolar I disorder (must be diagnosed with mania): The 12-month prevalence rate is estimated at approximately 0.6 percent. Lifetime male-to-female prevalence ratio is approximately 1:1:1 • Bipolar II disorder (diagnosis of hypomania): The 12-month prevalence rate is estimated at 0.8 percent in US; 0.3% internationally. • Cyclothymic disorder: This is a more chronic but less intense manifestation of bipolar-like symptoms. Lifetime prevalence is estimated to be between 0.4 percent and 1 percent. • Co-occurring mental disorders are common, with the most frequent disorders being any anxiety disorder (e.g., panic attacks, social anxiety disorder [social phobia], specific phobia), occurring in approximately three-fourths of individuals • ADHD, any disruptive, impulse-control, or conduct disorder (e.g., intermittent explosive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder), and any substance use disorder (e.g., alcohol use disorder) occur in over half of individuals with bipolar I disorder. • Adults with bipolar I disorder have high rates of serious and/or untreated co-occurring medical conditions. Metabolic syndrome and migraine are more common among individuals with bipolar COMORBIDITY FOR BIPOLAR I disorder than in the general population. • More than half of individuals whose symptoms meet criteria for bipolar disorder have an alcohol use disorder, and those with • Bipolar II disorder is more often associated with one or more cooccurring mental disorders, with anxiety disorders being the most common. Approximately 60% of individuals with bipolar II disorder have three or more co-occurring mental disorders; 75% have an anxiety disorder; and 37% have a substance use disorder. • Children and adolescents with bipolar II disorder have a higher rate of co-occurring anxiety disorders and the anxiety disorder most often predates the bipolar disorder. Anxiety and substance use disorders occur in individuals with bipolar II disorder at a higher rate than in the general population. • Approximately 14% of individuals with bipolar II disorder have at least one lifetime eating disorder, with binge-eating disorder being more common than bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. • These commonly co-occurring disorders do not seem to follow a course of illness that is truly independent from that of the bipolar disorder, but rather have strong associations with mood states. For example, anxiety and eating disorders tend to associate most with depressive symptoms, and substance use disorders are moderately COMORBIDITY FOR BIPOLAR II Substance-related disorders and sleep disorders (i.e., difficulties in initiating and maintaining sleep) may be present in individuals with cyclothymic disorder. Most children with cyclothymic disorder treated in outpatient psychiatric settings have comorbid mental conditions; they are more likely than other pediatric patients with mental disorders to have comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. COMORBIDITY FOR CYCLOTHYMIC DISORDER Jane was the wife of a well-known surgeon and the loving mother of three children. The family lived in an old country house on the edge of town with plenty of room for family members and pets. Jane was nearly 50; the older children had moved out; the youngest son, 16-year-old Mike, was having substantial academic difficulties in school and seemed anxious. Jane brought Mike to the clinic to find out why he was having problems. As they entered the office, I observed that Jane was well-dressed, neat, vivacious, and personable; she had a bounce to her step. She began talking about her wonderful and successful family before she and Mike even reached their seats. Mike, by contrast, was quiet and reserved. He seemed resigned and perhaps relieved that he would have to say little during the session. By the time Jane sat down, she had mentioned the personal virtues and material achievement of her husband, and the brilliance and beauty of one of her older children, and she was proceeding to describe the second child. But before she finished she noticed a book on anxiety disorders and, having read voraciously on the subject, began a litany of various anxiety-related problems that might be troubling Mike. In the meantime, Mike sat in the corner with a small smile on his lips that seemed to be masking considerable distress and uncertainty over what his mother might do next. It became clear as the interview progressed that Mike suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder, which disturbed his concentration both in and out of school. He It also became clear that Jane herself was in the midst of a hypomanic episode, evident in her unbridled enthusiasm, grandiose perceptions, “uninterruptable” speech, and report that she needed little sleep these days. She was also easily distracted, as when she quickly switched from describing her children to the book on the table. When asked about her own psychological state, Jane readily admitted that she was a “manic depressive” (the old name for bipolar disorder) and that she alternated rather rapidly between feeling on top of the world and feeling depressed; she was taking medication for her condition. I immediately wondered if Mike’s obsessions had anything to do with his mother’s condition. Mike was treated intensively for his obsessions and compulsions but made little progress. He said that life at home was difficult when his mother was depressed. She sometimes went to bed and stayed there for 3 weeks. During this time, she seemed be in a depressive stupor, essentially unable to move for days. It was up to the children to care for themselves and their mother, whom they fed by hand. Because the older children had now left home, much of the burden had fallen on Mike. Jane’s profound depressive episodes would remit after about 3 weeks, and she would immediately enter a hypomanic episode that might last several months or more. During hypomania, Jane was mostly funny, entertaining, and a delight to be with—if you could get a word in edgewise. Consultation with her therapist, an expert in the area, revealed that he had prescribed a number of medications REFERENCES American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Fifth ed.). Bangkok: IGroup Press. Barlow, D. H., & Durand, V. M. (2015). Abnormal psychology: an integrative approach (Seventh ed.). Singapore: Cengage Learning Asia Pte Ltd. Butcher, J. N., Mineka, S., & Hooley, J. M. (2014). Abnormal psychology (12th ed.). Boston: Pearson.