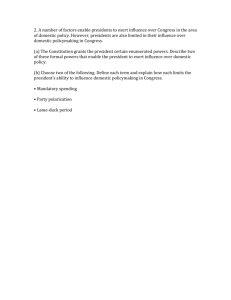

Presidential Powers Article Within the executive branch itself, the president has broad powers to manage national affairs and the workings of the federal government. The president can issue rules, regulations and instructions called executive orders, which have the binding force of law upon federal agencies. As commander-in-chief of the armed forces of the United States, the president may also call into federal service the state units of the National Guard. In times of war or national emergency, the Congress may grant the president even broader powers to manage the national economy and protect the security of the United States. The president chooses the heads of all executive departments and agencies together with hundreds of other high-ranking federal officials. The president may appoint anyone they deem best fills the position. The large majority of federal workers, however, are selected through the Civil Service system, in which appointment and promotion are based on ability and experience. Under the Constitution, the president is the federal official primarily responsible for the relations of the United States with foreign nations. Presidents appoint ambassadors, ministers and consuls -- subject to confirmation by the Senate -- and receive foreign ambassadors and other public officials. With the secretary of state, the president manages all official contacts with foreign governments. On occasion, the president may personally participate in summit conferences where chiefs of state meet for direct consultation. Thus, President Woodrow Wilson headed the American delegation to the Paris conference at the end of World War I; President Franklin D. Roosevelt conferred with Allied leaders at sea, in Africa and in Asia during World War II; and every president since Roosevelt has met with world statesmen to discuss economic and political issues, and to reach bilateral and multilateral agreements. Through the Department of State, the president is responsible for the protection of Americans abroad and of foreign nationals in the United States. Presidents decide whether to recognize new nations and new governments, and negotiate treaties with other nations, which are binding on the United States when approved by two-thirds of the Senate. The president may also negotiate "executive agreements" with foreign powers that are not subject to Senate confirmation. After the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon Administrations had spent nearly a decade committing U.S. troops to Southeast Asia without Congressional approval, Congress responded by passing the War Powers Resolution in 1973. The War Powers Resolution requires that the President communicate to Congress the committal of troops within 48 hours. Further, the statute requires the President to remove all troops after 60 days if Congress has not granted an extension. When passed, Congress intended the War Powers Resolution to halt the erosion of Congress's ability to participate in war-making decisions. This resolution, however, has not been as effective as Congress likely intended (see the "War Powers Resolution" section in the Commander in Chief Powers article). The terrorist attacks against the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001 further complicated the issue of war powers shared between the President and Congress. After September 11, the United States Congress passed the Authorization for Use of Military Force against Terrorists (AUMF). When the United States invaded Afghanistan, the U.S. military rounded up alleged members of the Taliban and those fighting against U.S. forces. The military then placed these "detainees" at a U.S. base located at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba at the direction of the Bush Administration who designed the plan under the premise that federal court jurisdiction did not reach the base. Consequently, the Bush Administration and military believed that the detainees could not avail themselves of habeas corpus and certain protections guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. Among the president's constitutional powers is that of appointing important public officials; presidential nomination of federal judges, including members of the Supreme Court, is subject to confirmation by the Senate. Another significant power is that of granting a full or conditional pardon to anyone convicted of breaking a federal law -- except in a case of impeachment. The pardoning power has come to embrace the power to shorten prison terms and reduce fines. Presidents Who Increased Executive Powers: George Washington set the precedent; when Congress requested documents pertaining to the controversial Jay Treaty, he refused to turn them over, introducing the doctrine of executive privilege and making a point about the autonomy of the executive branch. Over the course of the nineteenth century, other presidents added new weapons to the office's arsenal of powers. Andrew Jackson was the first to make extensive use of the veto and Abraham Lincoln read broadly into his wartime powers as commander-in-chief. But with Teddy Roosevelt and the arrival of a new, more complex century, the office's power grew at an even faster clip. While president, Jefferson's principles were tested in many ways. For example, in order to purchase the Louisiana Territory from France he was willing to expand his narrow interpretation of the Constitution. But Jefferson stood firm in ending the importation of slaves and maintaining his view of the separation of church and state. In the end, Jefferson completed two full and eventful terms as president. He also paved the way for James Madison and James Monroe, his political protégés, to succeed him in the presidency. Under FDR, the American federal government assumed new and powerful roles in the nation's economy, in its corporate life, and in the health, welfare, and well-being of its citizens. The federal government in 1935 guaranteed unions the right to organize and bargain collectively, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 established a mechanism for putting a floor under wages and a ceiling on hours that continues to this day. It provided, in 1935, financial aid to the aged, infirm, and unemployed when they could no longer provide for themselves. Beginning in 1933, it helped rural and agricultural America with price supports and development programs when these sectors could barely survive. Finally, by embracing an activist fiscal policy after 1937, the government assumed responsibility for smoothing out the rough spots in the American economy.