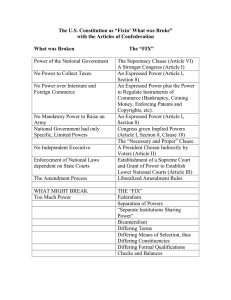

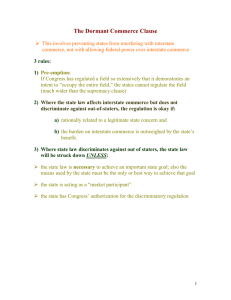

Constitutional Law Outline I. Introduction: The Marshall Court and the Federalist Constitution A. Interpreting the Constitution 1. Scope of Congressional Powers McCulloch v. Maryland (1815): Necessary and Proper Clause allows the Congress to do what is necessary in order to exercise its enumerated powers, without an explicit constitutional provision allowing the action. The Constitution should be read as a “document intended to endure for the ages and, consequently adapted to the various crises of human affairs.” Enumerated Powers: These include the powers to tax, spend, borrow money, fund the military, coin money, etc. The power to tax is the power to destroy. The federal government is limited in its powers but is supreme with its sphere. Necessary does not mean indispensable, but instead something which is reasonably related to an enumerated power. As long as the end is legitimate and the means are plainly adapted to that legitimate end, the act is constitutional. The supremacy of the federal government makes state sovereignty subordinate to the federal government. Taxes on federal property and employees are permitted for revenue collection only, not for regulating the federal government. 2. Modalities of Interpretation a. Appeals to the Text Tends to be the preserve of originalists and has two strands. One focuses on the intent of the founders (Scalia) while another focuses on the original meaning of the words themselves (Thomas). b. Constitutional Structure Infers the intended structure of the government from provisions of the Constitution. The powers of the different branches of government create a constitutionally ordained balance of power that must be maintained. c. Prudentialism/Consequentialism Focuses on the reasonable action and on the potential consequences of a decision. Will tend to avoid decisions that are controversial with the public and other branches of the government. d. History Focuses on the historical events surrounding the adoption or rejection of certain provisions. Constitutional meaning can be inferred from both pre and post ratification history. Can also be used to argue for learning from the mistakes of the past to avoid similar errors in judgment. e. Precedent Looks to past court decisions, actions by Congress, the President and state or local governments, as well as traditions. Precedents from state courts are not binding on the federal courts, but can be used to provide persuasive arguments. The blind adherence to precedent ignores the changes in circumstances over time as well as the actual text of the Constitution. Precedent does help create and maintain a stable body of law, though it can allow misguided decisions to remain in effect. f. National/Narrative Ethos Considers whether a decision is faithful to the identity or destiny of the nation, its deepest commitments or an important aspect of national character. 3. Judicial Review The principle of judicial review is not explicitly provided for in the Constitution. In Marbury v. Madison (1803), the court established the power of the Supreme Court to review acts of Congress and acts of the executive for constitutionality, creating the principle of judicial review. The decision in Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1821) established the precedent that the Supreme Court can review state court decisions. Judicial Review in a Democratic Polity The Countermajoritarian Difficulty In striking down acts of Congress and state legislatures, the Court will stymie the will of the people. Justifications for Judicial Review a. Supervising Inter and Intra Governmental Relations Judicial review helps to prevent states from usurping federal powers and vice versa. It also creates a uniform federal standard on certain issues. b. Preserving Fundamental Values The Court is unelected and is therefore not responsive to the vagaries of the people like a legislature would be. This puts the courts in a position to protect the fundamental values of the Constitution, even when it is unpopular, i.e. Brown c. Protecting the Integrity of the Democratic Process The court is also well positioned to use constitutional review to reinforce freedom of speech/press, protect voting rights and protect minorities from the tyranny of the majority. See Footnote 4, Carolene Products. The Countermajoritarian Difficulty Countered Besides the Court, there are other parts of the federal government that are unmajoritarian, such as the Electoral College or representation in the Senate. Furthermore, unelected cabinet members can exert undue influence on the President. The appointment of Justices by popularly elected Senators can serve as a counterweight to some of the Court’s countermajoritarian tendencies. See Bork confirmation. The Court can, in some cases, act as a counterweight to these unmajoritarian practices. 4. Presidential Interpretation Each branch of government is responsible to some degree to interpret the Constitution. The President can veto legislation that he considers to be unconstitutional and can refuse to enforce a act that he considers to be unconstitutional. This practice was upheld in Meyer v. United States. Jackson’s Veto Message Because the Bank of the United States takes away the power of the states to tax, Jackson believes it is an unconstitutional entity and refuses to sign legislation that would extend its charter. Jackson argues that the precedent set in McCulloch is not decisive authority of the Bank’s constitutionality. This stands in direct contrast to the common law tradition of treating precedent as being authoritative. Jackson believes that each has the right to interpret the Constitution and act that interpretation. AG Dellinger’s Guideposts to When Executive Refusal is Appropriate 1. The President should presume that all Congressional enactments are constitutional and construe them in a way to avoid constitutional problems. 2. If the President believes that the Supreme Court would uphold an enactment as constitutional, he should execute it regardless of personal doubts of its constitutionality. 3. Only when the President has doubts of an enactment’s constitutionality and believes that the Supreme Court will overturn it that he should refuse to execute it. 4. Where both the President’s and the Court’s views are likely to converge, the President should consider the consequences of refusing to enforce the enactment and the likelihood of judicial resolution. 5. The President has an enhanced responsibility to resist unconstitutional encroachments on Presidential power by the legislature, unless he believes that the Court would not rule in his favor. 6. The fact that a previous President signed a piece of legislation should not prevent the current President from refusing to enforce the law if he believes it to be unconstitutional. 7. In conclusion, the President has the authority to sign legislation containing desirable elements while refusing to enforce constitutionally questionable elements. II. The Jacksonian Era and Slavery Natural Law Tradition in America The natural law is a concept that there are certain universal and immutable principles, including the rights to “life, liberty and property” as expounded by John Locke and famously adapted in the Declaration of Independence. Natural law is law that transcends humanity and is a body of universal moral principles, while positive law is law that has been written or declared. Explicit Federal Constitutional Protection of Rights Judicial protection of individual rights arose out of Article I, Sections 9 & 10, which forbade the states from issuing bills of attainder, applying ex post facto law and impairing the obligations of contracts. These first two restrictions were also extended to the federal government as were limits on the government’s ability to suspend habeas corpus. Ninth Amendment The Ninth Amendment stated that the rights of the people were not limited to those enumerated in the Bill of Rights. This was done to allay fears that the Bill of Rights would be interpreted as the outer limits of the people’s rights. Tenth Amendment The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people. Calder v. Bull (1798) The Ex Post Facto Clause applies to criminal laws that have one or more of the following effects: 1. A law that makes an action that was done before the passing of the law and legal at that time a criminal offense. 2. A law that aggravates a crime and makes it a greater offense than when it was committed. 3. A law that increases the punishment for a crime than when the crime was committed. 4. A law that changes the rules for legal evidence and receives less or different testimony than was required at the time of the offense in order to convict the offender. Fletcher v. Peck (1810) The Court held that the right to property precedes the Constitution and did not need to be enumerated to be recognized. Acts of the legislature that take property without compensation are against natural law and the social contract. The primary function of government in a Lockian conception was the protection of private property. Slavery and the Constitution Prior to the passage of the 13th Amendment, slavery was a constitutional practice. There were several Constitutional provisions that protected slavery, including: Article I, Section 2: Required the apportionment of the House to be based on the whole number of free persons and three-fifths of “all others,” i.e. slaves. Article I, Section 9: Barred Congress from outlawing the importation of slaves until 1808. Congress did so at that time. Article IV, Section 2: Contained the Fugitive Slave Clause, which required free states to extradite escaped slaves. Many saw slavery as something beyond the regulatory power of the federal government, while states had full power to regulate or outlaw the trade. By the 1830s, most Northern states had outlawed the slave trade. There were no slave states further north than Delaware or further west than Texas. By the 1850s, free states began to outnumber slave states. Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) This case centers on the conflict between the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and Pennsylvania’s anti self-help law. Under the federal law, an escaped slave must be extradited from a free state. This conflicted with the Pennsylvania law that barred a person from being removed from the Commonwealth by force for the purpose of enslaving that person, without a hearing to determine the person’s status. The court held that the Pennsylvania law was unconstitutional because it violated both the Fugitive Slave Clause and Supremacy Clause of the Constitution. Not allowing slaveowners to recapture escaped slaves was deemed to be an action that divested them of their property without due process, a violation of natural law. States do not need to use their resources to enforce federal law. Missouri Compromise of 1820 Missouri was admitted as a slave state and slavery was permitted south of Missouri on the condition that Maine would be admitted as a free state and slavery would be banned north of the 36.5th parallel north or west of the Mississippi river, except where slavery pre-existed. Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 Allowed for popular sovereignty on the slavery question for newly admitted states west of the Mississippi river or north of the 36.5th parallel north. Scott v. Sanford (Dred Scott Case) (1857) The plaintiff was a slave who was brought to Illinois and Upper Louisiana (present day Wisconsin) while his owner was stationed there in the military. The former was a free state while the latter was a free territory under the Missouri Compromise. Because of this, the plaintiff claimed that he was now free and sued for freedom in federal court. To having standing to sue in federal court under diversity jurisdiction, both parties must be citizens of different states. The plaintiff claims that he is a citizen of Missouri. The court holds that black people, free or slave, cannot be considered citizens of the United States. Chief Justice Taney holds that this is because their ancestors had been enslaved and a “perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one they had reduced to slavery.” Taney cites evidence of numerous legal restrictions on freedmen across the country, such as restrictions on voting rights and anti-miscegenation laws, as evidence of this fact. Additionally, freeing a slave brought into federal territory violates the owner’s Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, by depriving him of his property without due process of law. Taney considers the Constitution to be a pro-slavery document that bars black people from becoming citizens upon obtaining freedom. This decision is considered the anti-canonical decision in Supreme Court history, and was overturned by the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Frederick Douglass on the Constitution Unlike Taney, Douglass considers the Constitution to be an anti-slavery document. This is because it contemplates the elimination of the international slave trade in Article I, Section 9. Additionally, Douglass believes that the text is at worst ambiguous and can be reasonably interpreted by judges to be anti-slavery. III. The Civil War and Reconstruction A. Secession and The Union The Secessionists believed that secession was valid and that the Revolution against the British had the precedent that the people had the right to revolt against a government that does not represent their interests. President Lincoln believed that the Constitution created a perpetual and indissoluble union between the states and that secession was illegal. Emancipation Proclamation Lincoln initially did not allow his commanders to free slaves and believed that the Dred Scott decision had precluded any action by the president or legislature to outlaw slavery. Lincoln depended upon his powers as commander in chief to issue the proclamation, which allowed the military to seize the property of rebels in any territory captured from the Confederacy. This property included slaves. Justice Curtis, in a letter to President Lincoln, expressed concerns that the proclamation exceeded executive powers because it overrode valid state laws about the regulation of citizens and their property. Additionally, the proclamation deprived citizens of property without due process of law. Civil Rights Act of 1866 Following the freeing of the slaves, Congress wanted to protect the freedmen from abuse. When some expressed fears that granted civil rights to freedmen would grant them suffrage, a line was drawn between civil, social and political rights. Civil Rights: The right of blacks to be protected under the law as a citizen. Social Rights: The right of blacks to be treated equal to whites in social contexts. i.e. attending the same schools, using the same transportation, interracial marriage, etc. Political Rights: The right of blacks to vote, hold office or serve on juries. The Civil Rights Act was intended only to grant the first set of rights to the freedmen. B. Constitutional Amendment Thirteenth Amendment The Thirteenth Amendment granted Congress the power to pass legislation to outlaw slavery. The implication of the Amendment is that the Constitution may have originally been pro-slavery. C. Reconstruction and Reaction I: The Fourteenth Amendment Fourteenth Amendment Section 1 All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Section 5 The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article. The Fourteenth Amendment thus provided freedmen with birthright citizenship and made illegal for the states to take actions to discriminate against them. The Fourteenth Amendment is the wellspring of many constitutional rights and much constitutional litigation. D. Reconstruction and Reaction II: Privileges and Immunities and the Status of Women Slaughterhouse Cases (1873) This case was a challenge to a Louisiana law that mandated all slaughtering done in the City of New Orleans be done at a single slaughterhouse in order to confine the practice to a single location in the city and prevent the spread of disease. The city’s butchers argued that this state sanctioned monopoly deprived them of their privileges and immunities as citizens of Louisiana, of which would include the right to earn a living in their chosen field. The Court ruled against the butchers, holding that the Privileges and Immunities Clause affected on the rights of United States citizenship and not state citizenship. In 1873, the privileges and immunities of American citizenship were few, such as the right to travel between states or use navigable U.S. waterways. This decision had the effect of rendering the Privileges and Immunities Clause a nullity. Women’s Citizenship in Post-Bellum Era Women were not given the franchise and had only recently been given the right to own property in their own names. Bradwell v. Illinois (1873) This case was a challenge to the State of Illinois denying a law license to a woman under the Privileges and Immunities Clause. The Court solidified their narrow reading of the Clause by holding that the right to practice a profession was not a privilege or immunity of a United States citizen. The court used arguments referring to the separate spheres of men and women in justifying the decision. Minor v. Happersett (1875) The court held that women did not have the right to vote, because voting was not an inherent right of citizenship protected by the Privileges and Immunities Clause. The Court reasoned that because the Constitution did not grant citizens the right to vote, something the Court believes that the Constitution would have make explicit if it intended to do so. E. Reconstruction and Reaction III: The Reconstruction Amendments and Race Strauder v. West Virginia (1880) A black man who was convicted of murder by an all-white jury challenged a West Virginia law that barred black men from serving as jurors. The Supreme Court held that the exclusion of black jurors denied the plaintiff equal protection of the law in violation of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Did not mandate that the jury pool had to be proportionate to the population, only that black men not be excluded from the jury pool by law. Civil Rights Cases (1883) The Civil Rights Act of 1875 banned states from allowing discrimination in restaurants, inns and places of public amusement. When several such businesses discriminated against black customers, they sued for enforcement of the provisions of the Civil Rights Act. The Court ruled against the plaintiffs and held the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to be unconstitutional. This is because the Fourteenth Amendment authorized Congress to regulate only state action and not the actions of private individuals. Additionally, the Court did not consider the “mere discrimination on account of race or color” to be a “badge of servitude” in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment. Plessy v. Ferguson (1892) This case was a challenge to a Louisiana law that mandated that black and white passengers ride in separate railcars. The plaintiff claims that the law is in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court holds that the Louisiana law did not violate the Equal Protection Clause. The Court holds that the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to provide only legal equality between the races, not social equality. The infamous phrase “separate but equal” comes from this case. The majority held that as long as the facilities in use were equal, than it was perfectly legal to allow these facilities to remain segregated by race. Harlan’s Dissent Harlan believes that the Constitution is “color blind” and should “neither know nor tolerate classes amongst citizens.” Harlan believes that the Equal Protection Clause extends to social as well as legal equality. IV. The Lochner Era A. Substantive Due Process Substantive Due Process is a principle that allows courts to protect fundamental rights from government interference, even if the procedural protections are present or the right is not specifically mentioned in the Constitution. Substantive Due Process draws on the Due Process Clauses of the 5th and 14th Amendments, which bars the federal and state governments respectively from depriving citizens of life, liberty or property without due process of law. Lochner v. New York (1905) This case is a challenge to a New York statute that restricts the amount of hours a baker can work to ten in a single day and sixty in a single week. The Court held that the New York statute did violate the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment by denying freedom of contract. The court read the liberty and property prongs of the Due Process Clause together to synthesize a constitutionally protected right of freedom of contract. Any law that dictates the terms of an employment contract must be a reasonable exercise of the state’s police power. The majority believes that the law in this case is not and the court closely scrutinizes New York’s motivations for passing the law. The decision reads the Constitution as a document that endorses the system of laissez faire capitalism. Harlan’s Dissent Justice Harlan believes that the law passed by New York was a legitimate use of legislative authority and state police powers. He believes that the Court gave insufficient weight to the legitimate health concerns of the legislature in passing the law. Holmes’ Dissent Justice Holmes accuses the majority of engaging in judicial activism by reading the Constitution to “embody a specific economic theory”. In Holmes’ opinion, there are numerous other ways in which the state can interfere with freedom of contract, such as bans on usury or Sunday trading, that the Court would likely uphold. Holmes’ dissent is among the most famous and commonly cited dissents in the history of the Court. There is near universal agreement that Lochner was wrongly decided and is an infamous example of judicial activism. Kopich v. Kansas (1915) A challenge to Kansas law that forbade so-called “yellow dog” contracts, which were employment contracts that had a clause that made a worker promise not to join a union. The Supreme Court overturned this law on the same grounds as Lochner; that it is a state action that interfered with an employee’s freedom of contract. Muller v. Oregon (1908) This case was a challenge to an Oregon law that limited the number of hours women could work. Like the previous cases, it was challenged as an interference to an employee’s freedom of contract. Unlike in the other cases, the Court held that the state had a legitimate interest in protecting women and their capacity to perform maternal functions which outweighed the woman’s fundamental right to contract. Laws that paternalistically protected female workers were the only exceptions to the Lochner principle while it was operative law. This case was overturned by the decision in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital in 1923, which repudiated sex-based distinctions in freedom of contract due to the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment three years prior, which granted women the right to vote. B. Federalism and National Powers Commerce Clause Powers Commerce Clause: Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 Congress shall have the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, amongst the states and with Indian tribes. Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) This case was a dispute between the holder of a federal ferry license between New York and New Jersey and the holder of a license for the same ferry route issued by the New York legislature. Congress issued the plaintiff his license under a law that allowed Congress to regulate the coasting trade. The court held that the Commerce Clause allows Congress to regulate the navigation of waterways because commerce is more than the mere traffic of commodities, but also includes navigation. Champion v. Ames (1903) This case challenged the Federal Lottery Act of 1895, which made it illegal to send lottery tickets across state lines. The plaintiff was convicted under this act for shipping Paraguayan lottery tickets from Texas to California. The plaintiff argues that the trafficking of lottery tickets does not constitute as commerce. The five justice majority of the Court holds that the Act is Constitutional. This is because Commerce Clause power is plenary in nature and can be used as Congress sees fit within constitutional limits. This includes proscribing an entire class of products, such as lottery tickets. Congressional power to regulate interstate traffic is plenary, meaning it is complete in and of itself. Dissent The dissent does not believe lottery tickets to be articles of commerce, and thus believes them to be beyond the reach of Congressional regulation under the Commerce Clause. Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918) This case was a challenge to the Keating-Owens Act of 1916, which prohibited products made using the labor of children under fourteen from the stream of interstate commerce. The law was challenged as exceeding the power of Congress under the Commerce Clause. The Court held that the law exceeded the power of Congress under the Commerce Clause. This is because the Commerce Clause was not held to allow Congress to regulate manufacturing of goods made with child labor. This can be distinguished from past decisions that allowed Congressional bans of “inherently evil” things, like lottery tickets, alcohol or prostitution from interstate commerce. The Court did not believe that goods manufactured with child labor were immoral. The disparate regulation of wages and conditions from state to state may create economic inequality between the states, but such regulations are within the police powers of the states and are beyond Congressional control. Congress could not address the fact that the states had unequal labor laws, as that was within their police power under the 10th Amendment. Holmes’ Dissent Congress can regulate in this case because the goods made were manufactured in one state and sold in another, which is interstate commerce in his view. Holmes believes that the entire manufacturing process should be put under federal purview under the Commerce Clause. The exercise of federal Commerce Clause powers should not be curtailed because of the fact that it “might interfere with the domestic policy of any state.” In terms immorality, Holmes views the products of child labor to be just as immoral as the articles Congress is allowed to ban. It is illogical that prohibition is “permissible against strong drink but not against the product of ruined lives.” “If there is any matter upon which the civilized countries have agreed, it is the evil of premature and excessive child labor.” Constitutional Innovation in the Progressive Period 17th Amendment: Allowed direct allowed election of US Senators. 18th Amendment: Prohibition. Only Amendment to be repealed. 19th Amendment: Granted women the right to vote. V. New Deal Constitutionalism A. Emergence of the Modern Paradigm of Constitutional Scrutiny The Great Depression and its associated economic turmoil unleashed a wave of state and federal legislation that attempted to stabilize the economy and relieve the penury of the citizenry by various means. These various acts of legislation faced constitutional challenges, many premised on Lochnerian argues, such as the freedom of contract and economic substantive rights. Nebbia v. New York (1934) This case was a challenge to the constitutionality of a New York law that created the Milk Control Board to control the price of dairy, so as to support struggling dairy farmers. A grocer who sold milk below the minimum price challenged his fine and conviction on Due Process grounds. The Court applied a rational basis test to the law and held that the right to contract was not absolute and needed to be balanced against the state’s interest in maintaining the public welfare. In this case, the law was rationally related to the state’s goal of maintaining the welfare of the dairy farming industry and was not “unreasonable, arbitrary, or capricious.” As such, it was not unconstitutional, but a legitimate use of state police power that the Court had no authority to strike down. Home Building and Loan Ass’n v. Blaisdell (1934) This case was a challenge to a Minnesota law that imposed a moratorium on banks and other lenders foreclosing on the property of delinquent borrowers. The lenders argued that this was a violation of the Contracts Clause, which was understood as barring states from passing debtor’s relief laws. The Court did not dispute this reading of the Contracts Clause, but refuses to invalidate the Minnesota law, despite it being contrary to it because of emergency circumstances. The Court justifies the law on the grounds that the law was a justifiable use of state police power in the public interest in light of the dire economic conditions of the time. Despite the decisions in Nebbia and Blaisdell, the Court would frequently overturn New Deal legislation from 1935 to 1937. The Court contained three progressives, the arch-conservative Four Horsemen and two swing justices. All of the Four Horsemen were over seventy years old. This lead to President Roosevelt proposing a plan in early 1937 to add one justice to the court for every justice over the age of seventy, in an effort to get favorable decisions. While this plan failed, Roosevelt was ironically able to appoint eight justices following a string of retirements and deaths in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The decision in West Coast Hotel was handed down during the drama of the court packing controversy, and both swing justices joined the Three Musketeers against the Four Horsemen to hand down a pro-New Deal decision. This led to some allegations that the Court was responding to political pressure. West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937) This case was a challenge to a Washington State law that set a minimum wage for female workers. The challenge hinges on the freedom of contract principles expounded in Lochner and the rejection of such legislation in Adkins. The Court instead ruled that the Constitution allowed for the restriction of liberty of contract by state law when the restrictions protected the community, health, safety or vulnerable groups. This decision was an overturning and sharp rebuke of the decision in Lochner, holding that the right to liberty of contract was a qualified right, subject to “reasonable regulations and prohibitions, imposed in the interests of the community.” The Court applies a rational basis test for legislation that regulates wages or working hours, requiring a legitimate end of the state and the means used to be rationally related to that end. Carolene Products v. United States (1938) This case was a challenge to federal law that prohibited the shipment of “filled milk,” or skim milk compounded with fat, in interstate commerce. The law was challenged on both Due Process and Commerce Clause grounds. The Court held that the law was presumptively Constitutional and properly within legislative discretion. This was because it related to the legitimate end of insuring public health and the means of banning such products from interstate commerce was rationally related to this end. Footnote Four While the Court will apply a rational basis or minimum scrutiny and presume most legislation to be Constitutional, Footnote Four describes certain legislative acts that might give rise to a higher level of scrutiny. Strict scrutiny will be applied when: 1. A law appears on its face to violate a provision of the US Constitution, especially in the Bill of Rights, 2. A law restricts the political process that could repeal an undesirable law, such as restricting voting rights, organizing, disseminating information etc., or 3. A law discriminates against "discrete and insular" minorities, especially racial, religious, and national minorities and particularly those who lack sufficient numbers or power to seek redress through the political process. Williamson v. Lee Optical (1955) This case challenged an Oklahoma law that required a prescription before new lenses could be placed in eyeglass frames, a law that disadvantaged opticians, who could not write prescriptions. This law was challenged on Equal Protection grounds. The Court held that state laws regulating business are subject to a rational basis review and that the Court does not have to consider all possible motives for legislation the end is legitimate and the means are rationally related to the legitimate end. The Court on rational basis review and Lochnerism: "The day is gone when this court uses the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to strike down state laws, regulatory of business and industrial conditions, because they may be unwise, improvident, or out of harmony with a particular school of thought." The Court on the Equal Protection Clause: "The prohibition of the Equal Protection Clause goes no further than invidious discrimination.” B. National Powers in the Wake of the New Deal: The Emergence of the Modern Regulatory State The Commerce Clause provides the justification a large amount of diverse legislation, including most of the legislation that created the modern regulatory state. A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935) This case challenged a provision of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which allowed for local codes to be written regulating the sale, slaughter and price of chicken, among other things. Schechter’s company was cited for violations of these codes and argued that the powers granted in the Act exceeded Congressional Commerce Clause powers, since all of the chicken he sold was within the State of New York. The government argued that since most of Schechter’s chickens came from out of state, the code was legitimately regulating interstate commerce. The Court held that the NIRA violated the Commerce Clause, because it regulated an intrastate activity. Although the sale of live poultry was interstate commerce, the stream of commerce stopped at the slaughterhouse, since all of the meat was sold to in state buyers. This act of regulation violated the Tenth Amendment, because it interfered with the state’s police powers, regulating an activity “far removed from interstate commerce.” FDR Constitution Day Speech Supreme Court had struck down many of the New Deal laws. President Roosevelt claims that the Constitution is a people’s document and the president has the power to act unilaterally in national emergencies. NLRB v. Jones and Laughlin Steel (1937) This case was a challenge to the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which created the NLRB. The NLRB stepped in after J&L had fired ten employees from their Aliquippa, Pennsylvania plant. The Supreme Court ruled that the NLRA was a valid use of Commerce Clause powers to safeguard worker’s rights to self-representation. United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941) This case was a challenge to the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which barred from interstate shipment goods that were produced by workers paid less than the federal minimum wage. The government justified the legislation on Commerce Clause grounds, while the defendant argued that the Act violated the Tenth Amendment by reaching into matters that were local in nature. The Court upheld the FLSA, holding that Congress had the power to regulate working conditions under the Commerce Clause. The Act served the legitimate end of regulating the national economy by preventing states from allowing substandard labor practices to gain an advantage in interstate commerce. Commerce Clause powers extend to intrastate activities that are related to interstate commerce and some of the goods are produced for interstate commerce. The Court held that the Tenth Amendment is “but a truism” that does not in any way strip Congress of its enumerated powers under the Constitution. Wickard v. Filburn (1942) This case was a challenge to a provision in the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, which penalized farmers for going over their allotted amount of wheat they were allowed to grow on their farms. The law was meant to prevent prices from being driven down by excessive sale of crops on the open market. The defendant exceeded his allotted amount of wheat, but did not sell it, instead using it to feed animals on his farm. Since the wheat in question was never sold, let alone sold across state lines, the defendant argued that his actions did not constitute interstate commerce and that the Act was unconstitutional for regulating such activities. The Court held that the AAA was a Constitutional use of Commerce Clause powers. This was because even growing wheat for personal use beyond the allotted amount would have an effect on interstate commerce, since the farmer did not buy the wheat on the open market. The Court looked not at the effect of a single actor like the defendant, but instead looked at the cumulative effects of thousands of actors behaving as the defendant did, which would have a substantial effect on the price of wheat on the interstate market. As such activities that are local in nature but still have a substantially effect on interstate commerce can be regulated by the federal government. The Necessary and Proper Clause allows Congress to regulate production and consumption to further their regulation of interstate commerce. Since the regulation of wheat production was rationally related to Congress’ goal of supporting crop prices in the interstate market, the law is a Constitutional exercise of Commerce Clause powers. This case broadly expanded federal powers under the Commerce Clause and laid the foundation of the administrative state in the second half of the 20th century. The Commerce Clause was used to expand federal criminal law enforcement and as a workaround to the limitations of the 14th Amendment in civil rights legislation. VI. National Legislative Power: Recent and Contemporary Debates A. Civil Rights Legislation and the Warren Court Under the 14th Amendment, only government action could be outlawed and have specific legislation directed at it. In order to reach discriminatory acts of private individuals, Congress had to exercise its Commerce Clause powers. Civil Rights Act of 1964 Discrimination in places of public accommodations was outlawed if their operations effected interstate commerce. This included hotels with more than five rooms and restaurants serving goods that travelled through interstate commerce. United States v. Heart of Atlanta (1964) A challenge to Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination in public accommodations if their operations effected interstate commerce by the owner of the 216 room Heart of Atlanta motel as being beyond Congressional power. The Court ruled in favor of the government, holding that Congress acted within the scope of its Commerce Clause. While there would have been other ways to do this, it was still a valid exercise of Congressional powers. The business was strategically located near the junctions of I-75 and I-85 as well as two major Georgia highways, and 75 percent of the motels guests were from out of state. As such, the motel’s operations had a sufficient justification for Congressional regulation. Katzenbach v. McClung (1964) In this case, Ollie’s Barbeque, a restaurant in Birmingham, Alabama refused to seat black customers, only allowing them to take out orders. The government sought to enforce the Civil Rights Act against him, justifying the enforcement of the Act on Commerce Clause grounds. The Court found that the Civil Rights Act was justified under the Commerce Clause. This is because the Civil Rights Act was designed to prevent the artificial dampening of interstate commerce and travel caused by racial segregation in public accommodations. While the restaurant itself did not have a substantial impact on interstate commerce, the aggregate actions of businesses engaged in segregation had a “highly restrictive effect on interstate travel by Negros”, artificially dampening interstate commerce. Encouraging interstate commerce is a legitimate end of Congress and the Court found that Congressional action was rationally related to this end, based on Congressional findings. B. The Reach of the Commerce Clause United States v. Lopez (1995) This case was a challenge to the Gun Free School Zone Act of 1990, which made possession of a handgun near a school a federal offense. Congress justified this legislation on Commerce Clause grounds. This was because of the negative impact of gun violence on schooling and the importance of schooling in creating a skilled workforce for industry. The Court rejected Congress’ Commerce Clause rationale and held that the GFSZA exceeded Congressional power to regulate interstate commerce. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice Rehnquist identified three broad categories of activities Congress could regulate under the Commerce Clause: 1. The channels of interstate commerce 2. The instrumentalities of interstate commerce, or persons or things in interstate commerce 3. Activities that substantially affect or substantially relate to interstate commerce The Court found that education was too far removed from interstate commerce to be regulated under the Commerce Clause, and that allowing such a regulation to pass muster under the Congress Clause would make Congress capable of regulating anything distantly related to interstate commerce. The Court specifically looked to four factors in determining whether legislation represents a valid effort to use the Commerce Clause power to regulate activities that substantially affect interstate commerce: 1. Whether the activity was non-economic as opposed to economic activity; previous cases involved economic activity 2. Jurisdictional element: whether the gun had moved in interstate commerce 3. Whether there had been congressional findings of an economic link between guns and education 4. How attenuated the link was between the regulated activity and interstate commerce If a criminal activity does not have a substantial effect on interstate commerce, enforcement is left to the police power of the states, reserved to them by the 10th Amendment. United States v. Morrison (2000) This case was a challenge to the constitutionality of the Violence Against Women Act of 1994, which allowed for a federal civil remedy to victims of gender-based violence, even if no charges had been filed by the states. Congress invoked the Commerce Clause in passing the Act. The Court held that Congress exceeded its Commerce Clause power in passing VAWA, because Congressional Commerce Clause powers should be used only to regulate interstate economic activity. Much like in Lopez, the Court does not find the activity being regulated by VAWA to have enough of an impact on interstate commerce to justify Congressional intervention in a subject that would normally be under the purview of the state’s police powers. Gonzales v. Raich (2003) This case was a Challenge to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, in that it allowed the government to regulate intrastate growth of legal medical marijuana by having the DEA seize and destroy it. The Court upheld the Constitutionality of the CSA, holding that its passage was well within Congressional Commerce Clause powers. Additionally, the Court justifies the intervention in intrastate conduct on the aggregate principle expounded in Wickard v. Filburn. This aggregate principle applies to this case because the federal government has a legitimate interest in regulating and controlling the interstate growth of medicinal marijuana for personal use because it could be diverted into the illegal market. As such, the majority holds that seizing medical marijuana is a means rationally related to the federal government’s legitimate goal of controlling the interstate marijuana trade. O’Connor’s Dissent The federal government used the CSA to invade the police powers of the State of California. The State of California decided to permit the intrastate growth and use of small amounts of marijuana for medicinal purposes, which is a legitimate use of state police power. This use of state police power was stifled by the federal government in this case. Thomas’ Dissent Allowing the federal government to regulate the mere possession of a small amount of marijuana for personal, medicinal use where there is not evidence of a transaction is an extreme overreach of Congressional Commerce Clause powers. To allow this would be to interpret the Commerce Clause as granting the federal government unlimited regulatory powers. C. Necessary and Proper Clause Necessary and Proper Clause, Article I, Section 8: The Congress shall have Power ... To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof. National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012) This case was a challenge to the constitutionality of the individual mandate of the Affordable Care Act of 2009, colloquially known as Obamacare. The individual mandate required that all individuals either purchase health insurance or make a shared responsibility payment. Congress passed this law in order to reduce the cost of health care by spread around the costs of insurance more evenly and reducing the number of unpaid hospital bills. The federal government argues that the Act is justified under the Commerce Clause, Necessary and Proper Clause and the Taxing and Spending Power. The Court holds that the individual mandate exceeds Congressional power under the Necessary and Proper Clause. While Congressional authority under the Necessary and Proper Clause is rather broad, it must be “derivative of a granted power” to be a valid exercise of power. Unlike the law in Wickard, which involved regulating preexisting economic activity, the individual mandate compels non-actors to enter the market. The Commerce Clause presupposes existing commercial activity. The federal government cannot regulate economic inactivity that will have an aggregate effect on interstate commerce. Allowing the government to regulate inactivity would allow for regulation of a vast amount of behaviors. Dissent The states were unable to solve the free rider/collective action problem or regulate the insurance market. Only federal intervention in the insurance market could effectively regulate it. Comstock v. United States (2010) This case is a challenge to the Adam Walsh Child Protection Act, which required the civil commitment of certain people already in federal custody. The plaintiff was convicted of possession of child pornography and was deemed to be a sexually dangerous person and was subject to civil commitment after serving his sentence. The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Act under the Necessary and Proper Clause. The Court has five considerations on which it based this decision: 1. The Necessary and Proper Clause grants Congress broad power to enact laws that are "rationally related" and "reasonably adapted" to executing the other enumerated powers. 2. The statute at issue "constitutes a modest addition" to related statutes that have existed for many decades. 3. The statute in question reasonably extends longstanding policy. 4. The statute properly accounts for state interests, by ending the federal government's role "with respect to an individual covered by the statute" whenever a state requests. 5. The statute is narrowly tailored to only address the legitimate federal interest. D. The Taxing and Spending Power Taxing and Spending Clause, Article I, Section 8, Clause 1: The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States. Sebelius (cont.) Although Congress did not invoke the Taxing and Spending Power in passing the ACA, the federal government added an argument that the individual mandate was tax on people who did not purchase health insurance. The Supreme Court held that the individual mandate was a valid exercise of Congressional taxing and spending powers, despite Congress not invoking that power. The Court is bound to the canon of constitutional avoidance, which dictates that a federal court should avoid ruling on constitutional grounds if a decision can be reached on other grounds. It is plausible for the individual mandate’s shared responsibility payment to be a tax because: 1. It is collected by the IRS 2. It is due at the same time as income taxes 3. It is used as a means of revenue collection. Courts have historically given deference to Congressional taxation powers, with the only limit being that penalties cannot be enforced under the guise of taxes. The taxing and spending clause has been interpreted broadly, with any spending for the general welfare that does not violate the Constitution being a legitimate exercise of the power. Congress also has the power to define what the general welfare is, as well as attach conditions to money given to the states, allowing the federal government to influence state policy decisions. South Dakota v. Dole (1987) The state of South Dakota challenged the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984, which withheld 10 percent of federal highway funds from states that did not maintain a minimum drinking age of 21. South Dakota, which had a drinking age of 19 for beer challenged the law. The Court held that the NMDA was a valid exercise of the spending power because there was a rational relationship between building safe highways and the regulation of alcohol sales. The Court allows Congress to attach conditions to spending bills, so long as the spending withheld is not coercive. Otherwise, the Court gives Congress wide deference in its exercise of spending powers. E. Implied Limits on Federal Regulation of the States The court has in recent decades, the Supreme Court has brought back the Tenth Amendment as a constraint on federal power. Anti-commandeering: The federal government cannot compel the states to enforce certain federal laws. New York v. United States (1992) This case was a challenge to the Low-Level Radioactive Waste Amendments Act, which forced the states to “take title” of and assume liability for radioactive waste in state if the state failed to comply with the law. The Court held that this provision of the Act violated the Tenth Amendment, because it coerced the states into enforcing federal law. Printz v. United States (1997) This case is a challenge to a provision in the Brady Act, which had local law enforcement perform the required background checks for handgun purchases while the federal database was being set up. The Court held that this provision violated the Tenth Amendment, because it commandeered local officials into implementing federal policy. The Court looked at the historical practice of Congress avoiding the practice of using state officials to enforce federal laws, as well as the structural concerns over separation of powers, in that having states enforce federal law encroached on the powers of the executive branch. VII. The Modern Debate over Racial Equality A. Brown and Its Legacy Under the Equal Protection Clause, no state shall deny any person equal protection of law. For the first half of the 20th century, equal protection of law was understood as protecting solely equality of legal rights. This was the crux of the separate but equal principle from Plessy. Brown v. Board of Education (1954) This case was a challenge to the practice of school segregation, as well as the separate but equal principle expounded in Plessy. All but one of the plaintiffs in the initial case had lost their cases in the lower court, with the Delaware court finding the schools in question to be unequal. The Supreme Court overturned Plessy and held that separate schools were inherently unequal. The Court could not find an original intent of the framers of the 14th Amendment as to its relation to public schooling because public schooling was nonexistent at the time of ratification and there was no consensus as to the Amendment’s meaning. The Court instead decided to interpret the 14th Amendment in the light of the current moment. The Court found that segregation, even if facilities were equivalent, was an inherently unequal practice contrary to the Equal Protection Clause because of the negative psychological effects it had on black children. Segregation created an inferiority in black children, disincentivizing them from learning and perpetuating the racist status quo. The Court decided this case in light of its ethical commitment. Bolling v. Sharpe (1954) This case was a companion case to Brown, challenging the segregation of Washington, D.C. public schools under the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment. The 14th Amendment had been modeled on the 5th Amendment, but the latter lacked an Equal Protection Clause. The Court ruled segregation by the federal government to be unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment. This was achieved through reverse incorporation, which applied the Equal Protection Clause to actions of the federal government. The concepts of equal protection and due process were held to be closely related and both part of American ideal of fairness. The court held that it was unthinkable that the Constitution would impose less of a duty onto the federal government than the one imposed upon the states. Brown II: Required that the decision in Brown be made with “all deliberate speed.” This requires a good faith effort on the part of the states to integrate their schools. Lower federal courts were used to enforce desegregation, as well as other Congressional legislation on the 14th Amendment. Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1964) In response to an order to integrate the county’s school system in June 1959, the County Board of Education shut down the county’s public school system and instead disbursed tuition grants for all students, regardless of race, for private schools. Since there were no private schools in the area that took black students, this had the effect of depriving black students of access to education. The Court held this practice to be unconstitutional and ordered the schools reopen. It was held that denying black students the action to education was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. This case was the first time that the Supreme Court ordered a county government to exercise its power of taxation. It was this unusual level of intervention that caused Justices Clark and Harlan to dissent, holding that federal courts are empowered to order the reopening of public schools in Prince Edward County. Some states offered what were called freedom of choice plans, which allowed parents to choose which schools they wanted their children to attend. This had the effect of perpetuating the segregation of schools in the area. Green v. County School Board of New Kent County (1968) The Court held that freedom of choice plans were constitutional, but that many of them were ineffective at implementing integration. The specific freedom of choice plan of New Kent County was held to be unconstitutional. Following the decision, the county school board organized the schools along grade level and not racial lines. The Meaning of Desegregation and Busing There was disagreement as to what desegregation meant. Given the extent of residential segregation at the time, many school districts that were not explicitly segregated were not integrated either. Some courts responded to this de facto segregation by ordering inter-district school busing. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971) While resistance to integration was relatively weak in North Carolina, the situation was more complicated in the City of Charlotte, due to deeply intrenched residential segregation. As a result of this, most of the city’s black students still attended schools that were de facto segregated. A district court judge had ordered mandatory busing as the only way to redress the racial imbalance and a fractured decision by the Fourth Circuit upheld the order. The Court upheld the order and held that mandatory busing was an adequate remedy for segregated schools, even when this segregation was the result of selection of students based on geographic proximity and not on an intentional policy of segregation. Milliken v. Bradley (1974) A district court judge ordered busing to remedy racially imbalanced schools in Detroit, which were the product of the city being among the most residentially segregated in the country. Much like the City of Charlotte, the City of Detroit had no explicit policy of segregation, but the district court and Sixth Circuit both held that Detroit and the State of Michigan had a responsibility to integrate the Detroit school system, The Supreme Court reversed these lower court decisions, holding that school districts were only responsible for desegregation if they had explicit segregationist policies in the past. The Court held that desegregation was the “dismantling of a dual school system,” not the creation of a racial balance within “each school, grade or classroom.” The Court also emphasized the importance of local control over schools. B. The Anti-Discrimination Principle: Anti-Classification and Anti-Subordination There are two schools of thought in anti-discrimination: Anti-Classification and AntiSubordination. Anti-Classification: This school of thought is opposed to laws that classify citizens based on race. Anti-Subordination: This school of thought is opposed to laws that perpetuate the inferior status of one race relative to another, even when such an intent is not explicitly stated. Suspect Classification Doctrine Koreamtsu v. United States (1944) This case was a challenge to the executive order which excluded all people of Japanese descent from the West Coast states and sent them to internment camps. The plaintiff claims that the mandatory relocation is a violation of the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment. The Court, citing Footnote Four from Carolene Products, will apply strict scrutiny to acts of the government that discriminate on the basis of race. Strict scrutiny requires that the ends of the government be compelling and the means be narrowly tailored. Despite stating that strict scrutiny will be applied, the Court showed deference to the military’s judgment and held that the interment was warranted on national security grounds. Dissent Justice Murphy saw Japanese exclusion as “falling into the ugly abyss of racism,” and objected to the Court’s upholding of a plainly racist action. He used the differing treatments of German and Italian Americans compared to Japanese Americans to prove that the internments were motivated by racial animus and not military necessity. Justice Murphy’s dissent is also the first time the word “racism” appears in a Supreme Court opinion. Justice Jackson objects to the level of deference shown to the military by the majority. He recognizes that the Court may not be able to enforce its decision, but still would rule the internment to be unconstitutional. While an unconstitutional military will last for as long as an emergency and may be rescinded sooner, the Court legitimizing such an action will have lasting consequences. The principle of racial exclusion in times of emergency then “lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.” While Korematsu is considered an anti-canonical decision and was overturned in Hawaii v. Trump in 2018, it is also the first case to hold that strict scrutiny should apply in cases of race based discrimination. C. Defining Discrimination “Based On” Race 1. Discriminatory Intention Loving v. Virginia (1967) This case is a challenge to Virginia’s anti-miscegenation statute, which banned interracial marriage. The plaintiffs argue that this statute violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The state argued that it was not a violation, since both parties would be punished equally. The Court strikes down the statute as unconstitutional, being in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. The court applied strict scrutiny because the Virginia law clearly involved racial classifications. Applying strict scrutiny, the Court found that the Commonwealth’s justification of preserving racial integrity was not compelling or even legitimate. The law is a clear example of a race based distinction, which the Court finds to be inherently suspect. Reasons for Strict Scrutiny in Racial Classification Political Process Rationale: Since racial minorities often lack adequate representation in the political process, judicial intervention is justified so such groups can have their rights protected. Immutable Characteristic: Since race is a characteristic beyond the control of the individual, it is unfair to burden someone on the basis of race. Facially Neutral Laws A law does not have to be discriminatory on its face to be a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. A facially neutral law can be unconstitutional if it was passed with a discriminatory intent. Ho Ah Kow v. Nunan (1879) This case was a challenge to a San Francisco ordinance that required all men in county jail to have their heads shaved. The law does not specify any racial categories, but was passed to target Chinese men, because it was a custom at the time for Chinese men to shave the front of their scalp and keep the remaining hair in a long braid or queue. The Court held that the ordinance was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause, because the law imposed a cruel and demeaning punishment to a person under the jurisdiction of the United States. Although the law was facially neutral, it was commonly understood as targeting Chinese men, being colloquially known as the “Queue Ordinance.” Facially Neutral Law Without Proof of Race Based Intent Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971) This case challenged the practices of the Duke Power Company, which required employees have a high school diploma for its higher paid jobs. While this company policy was facially neutral, it had the effect of shutting black employees out from higher paid positions. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in employment based on race, color, religion, national origin or sex. There are exceptions based on bona fide occupational qualifications. The Court, ruling on the grounds of Title VII and not the Constitution, held that if job qualifications have a disparate impact on minority groups, the business must demonstrate that the qualifications are reasonably related to the job for which the qualifications are required. Washington v. Davis (1976) This case is a challenge to the hiring practices of the Washington, D.C. Police Department, which included test of verbal skills (Test 21) which had a disproportionately negative impact on black applicants. The plaintiffs sued under both the 5th Amendment Due Process Clause and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, claiming that the tests constituted impermissible employment discrimination. The Court that under the Equal Protection Clause a law is not unconstitutional if it has a racially disparate impact, only if it is passed with a discriminatory motive. Massachusetts v. Feeney (1979) This case was a challenge to a Massachusetts law that gave absolute preference for veterans in hiring for civil service position. At that time, 98 percent of veterans were men, which caused the law to have a disproportionate impact on women. The Court held that this law did not violate the Equal Protection Clause because of the law’s gender neutral language. 2. Race and the Criminal Process United States v. Clary (1994, Eastern District of Missouri) This case challenged the 100 to 1 sentencing disparity between possession of crack cocaine and possession of powder cocaine. 92.6 percent of all violators caught with crack were African American and the plaintiffs argue that the law was motivated by racial animus, with the congressional record showing that crack dealers were portrayed as young black men. Thus it is argued that the sentencing disparity is a violation of the 5th Amendment. The District Court upheld the constitutionality of the sentencing disparity, stating that Congress was motivated by the dangerous nature of crack cocaine and not racial animus approving the sentencing ratio. The fact that Congress could and did foresee disparate impact on black people is not sufficient to prove discriminatory intent. McCleskey v. Kemp (1987) In this case, a black inmate on death row in Georgia appeals his death sentence, arguing intentional discriminatory acts by the state. Among the evidence included complex statistical models that showed that black defendants were four times more likely to be condemned than white defendants. The Court held that the statistical evidence did not prove discriminatory intent, because the disparity did not prove conscious, deliberate bias on the part of law officials involved with the plaintiff’s case. The Court holds that disparate impact is not proof of discriminatory intent. D. Affirmative Action Affirmative action is a presumptively race based decision, but it is permitted in some circumstances. Bakke v. Regents of University of California (1978) This case is a challenge to the affirmative action program used by the University of California, which had a mandatory racial quota in admissions at its medical school. The plaintiff challenges this racial quota as being against both the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Court held that strict racial quotas in university admissions violated the Civil Rights Act. The Court applies strict scrutiny to this case, because of the use of racial classifications. It is not a compelling interest to remedy past discrimination, unless it is the past discrimination of an actor’s own past discrimination. The compelling interest Powell cites is the interest in maintaining a diverse student body. The means of using a racial quota is not narrowly tailored enough. The use of race as a plus factor would be narrowly tailored enough, as it would not be a rigidly applied system that shuts applicants out solely on the basis of race. City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co. (1989) The Court held that the city of Richmond’s minority set aside program, which set aside 30 percent of city contracts to minority business enterprises, was in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. The city failed investigate any race neutral methods that could rectify the problem of a lack of minority owned construction businesses and the 30 percent goal did not actually correspond to any actual measured injury. Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena (1995) This case was a challenge to the requirement that federal contractors give a certain amount of contracts to “disadvantaged” businesses, typically those owned by racial minorities or women. The Court held that racial qualifications used by the federal government must be narrowly tailored to further a compelling government interest. Reverse incorporation of the Equal Protection Clause was used to hold the federal government to the same standard as the states. Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) This case was a challenge to the affirmative action program in place at the University of Michigan Law School. The plaintiff argued that the school, in seeking to ensure a “critical mass” of students from minority groups, were operating a disguised quota system. The University argued that achieving this critical mass was a compelling government interest. The Court held that the school’s interest in obtaining “critical mass” was a compelling interest and the means the university used were narrowly tailored. As such, the school’s admissions system satisfied strict scrutiny. The Court did state that affirmative action should not be allowed to persist, in the interest of creating a colorblind society. The Court predicts that the use of racial preferences in admissions would no longer be necessary in 25 years. Dissent Justice Thomas holds that the use of racial preferences in the admissions process of a state school is a violation of the Equal Protection Clause and will be just as illegal in 25 years as it is at the moment of the decision. The court ignored the fact that more narrowly tailored programs create equally diverse classrooms and that there is evidence that the university was operating on a quota like system. VIII. Gender Classifications and Gender Equality A. The Intermediate Scrutiny Standard Prior to the 1970s the court applied a rational basis test to laws that distinguished on the basis of sex. This changed as a result of political and social changes that changed the role of women in society. Fronteiro v. United States (1973) This case is a challenge to a Department of Defense policy that allowed wives of servicemen to get automatic access to benefits, but did not allow the husbands of servicewomen to collect such benefits unless they were dependent upon their wives for more than half of their support. The DOD argued that this sex based distinction was necessary for administrative convenience. The Court held that legislation that drew sharp distinctions between the sexes could not be constitutionally justified simply on the basis of administrative convenience. The court did not apply a clearly standard of review, but did apply more than a rational basis test. Justice Brennan wanted strict scrutiny to be applied, but the rest of the Court decided not to apply strict scrutiny because the pending Equal Rights Amendment would have made such application automatic. The Court’s decision to defer to the political process meant that strict scrutiny would not become the standard of review used in sex discrimination cases. Intermediate Scrutiny Instead, sex discrimination cases apply the intermediate scrutiny standard of review first applied in Craig v. Boren (1976). To satisfy intermediate scrutiny a the law or policy being challenged must further an important government interest by means substantially related to that interest. United States v. Virginia (1996) This case is a challenge to the all-male admissions policy of the Virginia Military Institute. The 4th Circuit had ordered VMI to either allow women admission, create a separate academy for women or not take state funding. VMI chose the second option, but the academy for women was less prestigious and of a lower quality than VMI. The Court held that the exclusion of women from VMI was unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause. The Court applied intermediate scrutiny. The form of intermediate scrutiny that the Court applied, however, was one in that required the showing of exceedingly persuasive justification for a government action. Justice Scalia’s lone dissent argues that this requirement is closer to strict scrutiny than it is to intermediate scrutiny, while not following the standard of either of these levels of scrutiny. B. What is Discrimination “On the Basis of Sex” Massachusetts v. Feeney (1979) The Court held that the absolute preference for veterans was not unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause. The Court applied intermediate scrutiny and found that the hiring of veterans to reintegrate them into society was an important government interest and the absolute preference was substantially related to this interest. The policy, according to the majority, does not in any way intend to discriminate on the basis of sex. Dissent The dissent, in applying strict scrutiny, would find that the policy was not narrowly tailored to the reintegration of veterans into society. This is both because the policy grants all veterans, no longer how far removed they are from their service, preference and that the preference is absolute when using veteran’s status as a plus factor would achieve the same result. Additionally, the dissenters hold that the proof of discriminatory intent should come from the fact that the veteran’s absolute preference would have an obvious negative impact on female applicants, since only 2 percent of women in MA were veterans. Geduldig v. Aiello (1974) This case was a challenge to a California state-run disability insurance program that does not cover pregnancy related injuries that occurred in the absence of complications. The State of California justified this exclusion injuries from normal pregnancy because it saved the program money. The Court held that this was not discrimination on the basis of sex because it did not limit access to benefits for all women. The Court applied a rational basis test for discrimination based on pregnancy or childbirth and found that California’s actions were a reasonable way to save the system money. Title VII and Pregnancy Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, discrimination based on pregnancy or childbirth is barred and courts are to apply strict scrutiny to such claims. Nevada Dept. of Human Resources v. Hibbs (2005) This case is a challenge to the Family Medical Leave Act of 1993, which the plaintiff argues was an unconstitutional exercise of congressional power under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment, in that it allowed states to be sued, contrary to the sovereign immunity guaranteed to the states in federal court by the 11th Amendment and can only be abrogated by valid exercise of congressional powers under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment. The Court held that the FLMA was a valid exercise of congressional power under Section 5 of the 14th Amendment, and as such the Act could validly override state sovereign immunity. The FLMA was a valid exercise of Congressional power because it was passed in order to remedy sex based discrimination by the states. The sex based discrimination in question was the failure of the states to allow paternity leave. Although this case did not overturn Geduldig, the logic used by the majority stands in diametric opposition to the logic of that prior decision. IX. Modern Substantive Due Process: Privacy, Sexual Autonomy, Guns, Tradition A. Privacy Constitutionalized Fundamental Rights: These are rights that are protected under the 14th Amendment and are incorporated against the states. For a right to be fundamental, it must be implicit in the concept of ordered liberty or deeply rooted in the history and tradition of this Nation. Fundamental rights doctrine was a workaround to the limitations on privileges and immunities imposed by the Slaughterhouse decision, allowing the Court to incorporate sections of the Bill of Rights to apply to the states under the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses. Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942) The Court struck down an Oklahoma statute that required repeat offenders to be sterilized, holding that the right to marry and procreate were fundamental rights. Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) This case was a challenge to the Connecticut law that outlawed contraception. It was argued that the Connecticut law was against the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause. Connecticut claims the law is justified because it furthers the end of preventing adultery. The Court held that the Connecticut law was unconstitutional, violating the fundamental right to privacy, which was first applied in this case. The right to privacy is not explicitly provided for in the Bill of Rights, but is an unenumerated right that emerges from the “penumbras and emanations” of the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and the First Amendment right to free association. Justice Goldberg holds that the right to privacy was a right that was retained by the people under the Ninth Amendment, which presupposes the existence of rights not enumerated in the Bill of Rights. The Court holds that privacy in the marital relationship is a fundamental right, given the importance of the marital relationship in society. Restricting the use of contraceptives by married couples is not narrowly tailored to the state end of preventing adultery. Dissent Justice Black, although in disagreement with the Connecticut law as a matter of policy, cannot find Constitutional grounds on which to invalidate it. Black argues that the Constitution does not contain a right to privacy and criticizes the majority’s interpretation of the Ninth and Fourteenth Amendments. In particular, Black is perturbed by the Court embracing substantive due process and sees this as a return to the Lochner era, where the Court dictated matters of policy to the states in accordance with their own views. The right to privacy in sexual relationships was expanded to unmarried couples in Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972). Level of Abstraction Michael H. v. Gerald D. (1989) In this case, Michael had an affair with Gerald’s wife Carole, who gave birth to Victoria, who was Michael’s biological daughter, but Gerald’s legal daughter. Michael was denied visitation rights by a California family court and argues that as Victoria’s biological father, he has a fundamental right to paternity over Gerald. The Court held that an adulterous natural father does not have a fundamental right to assert paternity over the marital father. Justice Scalia held that under the traditions of the Nation, such a man does not have a fundamental right to paternity rights, given the importance of the unitary nature of the family. Scalia’s Footnote (joined by Rehnquist, explicitly repudiated by Kennedy and O’Connor) Scalia proposes a rule that would require the most specific applicable right be advocated for be applied to the analysis, in order to avoid judicial overreach. The protection of a fundamental right often requires it to be stated in the broadest terms possible, thus Scalia’s proposal would make it difficult for the Court to find violations of fundamental rights. B. Abortion, Autonomy, Equality Roe v. Wade (1973) This case is a challenge a Texas law that outlawed abortion. The plaintiff challenged this law under the right to privacy found under the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. Texas claimed the compelling interests of protecting maternal health and protecting future life were furthered by its anti-abortion law. The Court held that a woman had a fundamental right to access abortion, which meant that any regulations of such a right would have to satisfy strict scrutiny. The Court created a trimester framework to balance the fundamental rights of the woman and the interests of the state in protecting fetal life and maternal health. In the first trimester of pregnancy, the states can pass no laws that restrict access to abortion, because neither maternal health nor the life of the fetus is a compelling state interest at that time, leaving the decision to the woman and her doctor. From the end of the first trimester of pregnancy to the point of fetal viability, protecting maternal health became a compelling interest of the state, allowing for the state to make regulations reasonably related to protecting maternal health. At the point of viability, the third trimester, the state interest of preserving potential life becomes compelling and states can regulate or even ban late term abortions as long as there was an exception for cases where the mother’s life was in danger. Dissent The dissent does not see a privacy right and believes that the Court fashioned this right using substantive due process and engaged in judicial activism. Criticisms of Roe The decision in Roe was controversial both politically and legally. Politically the decision inspired a conservative, anti-abortion backlash and abortion became a politically salient issue. Legal scholars and judges, including some who agree with the result, have criticized the decision on multiple grounds. Archibald Cox, Watergate Prosecutor and Contemporary: "[Roe's] failure to confront the issue in principled terms leaves the opinion to read like a set of hospital rules and regulations.... Neither historian, nor layman, nor lawyer will be persuaded that all the prescriptions of Justice Blackmun are part of the Constitution." Ruth Bader Ginsburg: "[Roe was] about a doctor's freedom to practice his profession as he thinks best.... It wasn't woman-centered. It was physician-centered. John Paul Stevens: Roe should have been decided solely on the privacy issue and the trimester framework was not as acceptable from a legal standpoint and should have been avoided. William Saletan, Liberal Journalist: "Blackmun's [Supreme Court] papers vindicate every indictment of Roe: invention, overreach, arbitrariness, textual indifference." John Hart Ely, Professor, Yale School of Law: Roe "is not constitutional law and gives almost no sense of an obligation to try to be…What is frightening about Roe is that this super-protected right is not inferable from the language of the Constitution, the framers’ thinking respecting the specific problem in issue, any general value derivable from the provisions they included, or the nation's governmental structure." Lawrence Tribe, Professor, Harvard School of Law: "One of the most curious things about Roe is that, behind its own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found." Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) This case was a challenge to several abortion laws passed by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania that restricted women’s access to abortion. This laws included requiring doctors to give women informed consent, requiring spousal notice and parental consent for minors. These laws were challenged on the grounds that they improperly regulated a woman’s fundamental right to abortion. The majority of the Court upheld the central holding of Roe, that access to abortion is a fundamental constitutional right that touches on “intimate and personal choices…central to dignity and personal autonomy.” Applying the undue burden standard, the Court struck down the spousal consent requirement but upheld the other two laws. Casey and Stare Decisis The Court holds that stare decisis has to apply to the core holdings of Roe because of reliance interests. The Court holds that many people have ordered their lives around the possibility of getting an abortion and that taking away that right would be unfair. Past decisions can be overturned only when society’s understanding of certain rights have changed, such as separate but equal. The Court is also worried about legitimacy, feeling that the Court should not merely overturn past decisions because of political pressure. Overturning too many cases would also strain the public’s faith in the courts, since only so much error can be imputed to past courts. The Court feels that overturning too many past decisions makes it appear that the Court is responding to outside pressures and personnel changes and not making principled decisions. The Court abandoned the trimester framework from Roe, and created the undue burden standard. Under this, the state can regulate abortions at any point from viability and beyond without restrictions, and can regulate access to abortions so long as the regulation does not create an undue burden on the woman. It was held that the spousal notification requirement placed an undue burden on women because is exposed some women to the threat of domestic violence and retaliation and gave a husband veto power over his wife’s choice. The other laws are upheld as not being an undue burden. Dissent Roe was wrongly decided and the Court should have struck it down entirely instead of heavily modifying it. There is no fundamental right to privacy issue in relation to abortion, if there even is a fundamental right to privacy at all. The standard of review for abortion cases should be rational basis. Abortion cannot be a fundamental right because there is no long standing tradition of treating it as such in American society. In fact, the opposite is true, since traditionally, American states were allowed to legally proscribe abortion. Gonzales v. Carhart (2007) This case was a challenge to the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003, which banned the lateterm termination of pregnancy via intact dilation and extraction, colloquially referred to as partial birth abortions, if it affects interstate or foreign commerce. The Act was passed by Congress on Commerce Clause grounds, but was challenged by the defendant on Due Process grounds, in that it created an undue burden to a woman’s fundamental right to access abortion. The Court held that the PBABA did not create an undue burden to a woman’s right to access an abortion. The Court states that it is assuming that the holdings of Roe and Casey are valid for the sake of this decision, implying some justices do not think they are valid. The Court found that a central holding in Casey was that the state had an interest in protecting fetal life and that this law was furthering this interest in a manner that did not impose an undue burden. The Court showed a high level of deference to Congressional findings that stated that D&X procedures were never needed to protect women’s health, even when the District Court found contrary evidence. Instead, the Court found Congress could regulate as they pleased on the subject when the medical community had not yet reached a consensus. The concurrence by Justices Thomas and Scalia question whether Congress could justify such a law on Commerce Clause grounds, but do not rule on those grounds since the issue never came up. The two concurring Justices also state that current abortion jurisprudence has no basis in the Constitution. Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016) This case was a challenge to a Texas law, House Bill 2, that required doctors who performed abortions to have admitting privileges at a hospital with in 30 miles of the clinic and that abortion clinics meet the same standards as outpatient surgical facilities, which would require upgrades to the facilities and their staff. This had the effect of cutting the number of abortion clinics in the State of Texas by more than half. Texas claims that the laws are motivated by an interest in maintaining the safety of women receiving abortions, while Whole Woman’s Health claims that it is motivated by creating undue restrictions to abortion access. The Court holds that Texas cannot place undue burdens on the delivery of abortion services and that the challenged provisions of H.B. 2 did just that. This is because the Court found that this restrictions prevented women from exercising their right to access pre-viability abortions and that the laws were not justified on the grounds of protecting the health of the women. Undue burden is described as being one which creates substantial obstacles to abortion access. C. Sexual Orientation/Identity Bowers v. Hardwick (1987) This case was a challenge to a Georgia statute that outlawed sodomy, both by heterosexuals and homosexuals and called for 1 to 20 years of imprisonment for violations. Hardwick was caught engaged in homosexual acts by a police officer who was serving a warrant, and was subsequent arrested, although the charges were later dropped. The plaintiff claims that such laws violated the right to privacy. The Court rejects the plaintiff’s argument that anti-sodomy laws violate the right to privacy and holds that there is no fundamental right to engage in homosexual acts. This is because there is no historical precedent such a right being deeply rooted in the history and tradition of the Nation or implicit in the concept of ordered liberty. Justice White brusquely dismisses such an argument as “facetious at best.” He also adds a slippery slope argument, that if the state isn’t allowed to punish homosexual acts that occur within the home, the state wouldn’t be able to punish any sex crime that occurred within a home. Justice Powell concurs with the decision, but has 8th Amendment concerns about the possibility of 20 year sentence for a consensual act. Dissent Justice Blackmun argues that the majority is willfully blind to the privacy issues in this case, stating that sexual intimacy is “a sensitive, key relationship of human existence, central to family life, community welfare, and the development of human personality.” As such the right to privacy should be extended to it. Justice Stevens wrote a separate dissent about the state’s selective enforcement of the law against only homosexuals, since previous Court decisions declared the right to privacy in heterosexual relationships. Romer v. Evans (1996) This case is a challenge to Amendment 2, an amendment to the Colorado Constitution passed by referendum that forbade the passage of anti-discrimination laws for gays and lesbians by localities. The State of Colorado claims that they are preventing gays from obtaining special treatment, while the plaintiffs argue it is a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Court held that Amendment 2 did not satisfy even a rational basis review and was an unconstitutional denial of equal protection of the law to gay residents of Colorado. Justice Kennedy states that the law’s purpose was not to ensure that gay people did not get special treatment. Instead the amendment denied gay people protection of laws that protect other minority groups from arbitrary discrimination. Such a resulting disqualification of a class of people from protection of the laws is unprecedented in the Court’s jurisprudence and that animus towards gay people is the only possible explanation for such a sweeping and broad provision. This imposition of a disadvantage on a single minority group on the basis of animus is not even a legitimate government interest. As such, Amendment 2 does not even meet the rational basis test. Dissent Justice Scalia argues that the Court’s decision in this case is inconsistent with the decision in Bowers. This is because if it is legitimate to criminalize homosexual acts, then it should be legitimate to deny “special protection” to anyone with a propensity for such acts. Scalia argues that the Court is engaging in judicial activism and picking a side in the culture wars. Lawrence v. Texas (2003) This case is a challenge to a Texas law that outlawed “deviant sexual intercourse with individuals of the same sex. The case was argued both on Equal Protection grounds, in that it targeted only homosexuals and on liberty and privacy grounds, in a direct attempt to overturn Bowers. The Court held overturned Bowers, holding that homosexuals had a protected liberty interest to engage in private sexual activity and that moral disapproval of such an activity was not a legitimate justification to criminalize such activity. The issue in question is not the mere question of whether the right to have homosexual sex is a fundamental right, but whether homosexuals have a fundamental right to privacy like heterosexuals do. The right to privacy had previously been used to protect the sexual autonomy of heterosexuals from government intrusion and the Court is extending that same right to homosexuals. While traditional conceptions of liberty are important, the Court should consider developing mores when considering fundamental rights. While condemnation of homosexuality is firmly rooted in Judeo-Christian morality, it was never a long standing legal tradition in the United States, and the majority cannot use their control of the criminal justice apparatus to uphold or enforce such views. Additionally, recent trends in the United States and the Western world show a trend of increased decriminalization and tolerance.\ In sum: Bowers was wrong when it was decided and was even more wrong when it was overturned. Dissent Justice Scalia criticizes the majority for not adhering to the rigid application of stare decisis called for in Casey, calling their application of it opportunistic and inconsistent. Additionally, he argues that there is a long standing tradition of recognizing that homosexuality is wrong and that any repeal of such laws should occur through the democratic process. Additionally, Scalia believes that this too is an activist decision, motivated by the legal profession’s embrace of the so-called “homosexual agenda.” Scalia believes that it is a matter of time before the Court sanctions gay marriage, like the Canadian Supreme Court had done shortly before this decision. United States v. Windsor (2013) This case was a challenge to the Defense of Marriage Act of 1996, which defined marriage as being between one man and one woman for the purposes of federal law, thereby denying recognition to state sanctioned same-sex marriages. The plaintiff argues that DOMA violates the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment. The Court ruled that DOMA was unconstitutional, although the exact grounds on which it was struck down were unclear. On one hand, it was argued that DOMA denied couples in same sex marriages equal protection of the law, in violation of the reverse incorporated equal protection requirement of the 5th Amendment Due Process Clause. On the other hand, the Court also held that the federal government was acting contrary to federalism interests by not recognizing state sanctioned marriages as valid. This is because it is the states that have the police power to regulate marriage and not the federal government. The decision continues that denying recognition of same-sex partnerships is denying homosexuals equal dignity compared to the rest of the population. Dissent Justice Scalia vociferously objected to the decision, claiming that the Court should be involved in this case. In particular he criticized the Obama administration for continuing to enforce DOMA while failing to defend it. He additionally criticized the muddled reasoning of the majority and accuses them of engaging judicial activism. Additionally, Scalia claims that the decision effectively characterizes those who are opposed to same-sex marriage as “enemies of the human race. In allegedly characterizing opponents of same-sex marriage as being opposed to human decency, Scalia believes that the Court has given an argument to opponents of same-sex marriage bans at the state level. Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) This case is a challenge to state level bans on same-sex marriage on the grounds of the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the 14th Amendment. The Court held that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couple under the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the 14th Amendment. As such, all fifty states, the District of Columbia and the Insular Areas are required to perform and recognize same-sex marriages on the same terms as marriages of opposite-sex couples, with all of the accompanying rights and responsibilities. The Court cited both Loving v. Virginia, which recognized marriage as a fundamental right and Lawrence v. Texas, which recognized the right to privacy interest in sexual autonomy for all consenting adults, regardless of sexual orientation as precedential for finding a fundamental right for all to marry, regardless of sexual orientation. Bans on same sex marriages significantly burdened the liberty and equality of same-sex couples, denying them access to benefits and legitimacy offered to opposite-sex couples. Such bans were found to violate both the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses on these grounds. The Court justified in intervening in this case because of the substantial and continuing harm and instability and uncertainty caused by differing marriage laws between the states. While the Court recognizes the importance of the democratic process, protection and recognition of fundamental rights should not be left to the whims of the democratic process. The majority dismisses arguments that allowing same-sex marriage will harm the institution of marriage through the severing of the tie between marriage and procreation, since elderly and infertile people are allowed to marry. The majority points out that opponents of same-sex marriage will be protected by the First Amendment, and will still be allowed to freely express their opposition. Dissent Each dissenting Justice wrote separate opinions, on which some other dissenters joined. The recognition of same-sex marriage has no constitutional basis, and the majority is stretching the recognition of substantive rights to the breaking point. (Roberts) The dissenters see implications for religious liberty and believe that the opinion’s language unfairly attacks opponents of same-sex marriage. (Roberts) A ban on same-sex marriage would not have been considered to be a violation of the 14th Amendment at the time that it was adopted. (Scalia) Same sex marriage is not a fundamental right because it is not rooted in the traditions and history of the nation (Alito) The principle of substantive due process is to be rejected because it “invites judges to do exactly what the majority has done here—roam at large in the constitutional field guided only by their personal views as to the fundamental rights protected by [the Constitution].” (Thomas and Scalia) Additionally liberty has historically meant freedom from government action, not a right to a government entitlement. (Thomas and Scalia) Justice Scalia also criticized the Justice Kennedy’s use of rhapsodic prose in his decision, comparing it to the “mystical aphorisms of a fortune cookie.” D. Guns and “Self-Defense” Second Amendment: A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed Historical Interpretations of the Second Amendment United States v. Cruickshank (1876) The Supreme Court refused to apply the 2nd Amendment to the states holding that:"The right to bear arms is not granted by the Constitution; neither is it in any manner dependent upon that instrument for its existence. The Second Amendment means no more than that it shall not be infringed by Congress, and has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the National Government." United States v. Miller (1939) The Supreme Court upheld the National Firearms Act of 1934, which required short barreled shotguns and automatic weapons be registered with the ATF and a $200 tax be paid if the weapon were ever sold. This was because it was held that the Second Amendment does not protect those weapons that do not have “reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well-regulated militia.” District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) This case was a challenge to the Firearms Control Regulation Act of 1975, which banned handguns from the District of Columbia, only allowing the possession of rifles and shotguns in the home, provided that these weapons were left “unloaded and disassembled or bound by a trigger lock.” The lead plaintiff, Dick Heller, was a licensed police officer who could carry a handgun at work, but couldn’t keep one in his home. The Court holds that the right to bear arms is an individual right of the “people” unrelated to service in the militia, and the 2nd Amendment protects the use of that arm for traditionally legal purposes, such as self-defense. As a result, the handgun ban and the requirement of keeping rifles and shotguns unloaded and disassembled were in violation of the Second Amendment. Scalia looks back to the history of the right to bear arms, looking at the Anti-Federalist’s fears of the government disarming the people, the interpretation of the 2nd Amendment from the founding to the 19th century by courts, legislators and scholars and early drafts that 2nd Amendment to prove that it was originally understood to be an individual right. The 2nd Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose. Examples of valid restrictions include: Concealed carry bans Barring felons and the mentally ill access to firearms Laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places, such as schools or government buildings Imposing conditions and qualifications on commercial sale of firearms Banning the carrying of dangerous or unusual weapons (a la Miller) Scalia comes up with a common use standard to justify bans on dangerous or unusual weapons from civilian possession, such as machine guns or other military grade weaponry. The handgun ban and trigger lock requirement is an unconstitutional infringement on the right to self-defense and to bear arms and would fail to pass constitutional muster under any standard of review. This is because both requirements impose harsh restrictions on the use of commonly used arms in the home for self-defense. This is especially acute given the importance of self-defense in the home. Dissent Justice Stevens criticizes Justice Scalia’s reading of the Amendment and views the right to bear arms as being contingent upon service in the militia and was thus a collective right. Like Scalia, Stevens is able to find sources from around the time of the founding to bolster his viewpoint that the founders did not recognize the right to bear arms as an individual right, but instead as a collective one. Additionally, Stevens believes that the decision in Miller endorses a collective right interpretation of the 2nd Amendment, and that stare decisis should apply. McDonald v. Chicago (2010) This case is a challenge to an ordinance by the City of Chicago that banned the possession of handguns. This was challenge on 2nd Amendment grounds, with the hope that the 2nd Amendment would be incorporated against the states as a fundamental right. The Court held that the 2nd Amendment right to keep and bear arms for self-defense was a fundamental right applicable to the states by the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. As such, the City of Chicago’s ordinance was unconstitutional. The firearms mentioned in the Heller decision are assumed permissible and are not directly dealt with in this case. Much like in Heller, the Court holds that the right to bear arms is not an unqualified or unrestricted right, and cites the regulations cited in that case as being valid. Dissent Justice Stevens dissents, citing Cruikshank, stating that “The so-called incorporation question was squarely and, in my view, correctly resolved in the late 19th century,” when that case refused to incorporate the 2nd Amendment. Justice Breyer wrote: "In sum, the Framers did not write the Second Amendment in order to protect a private right of armed self-defense. There has been, and is, no consensus that the right is, or was, 'fundamental.'"