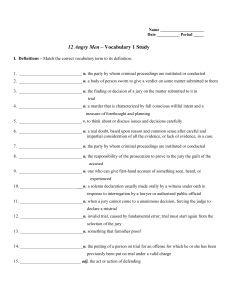

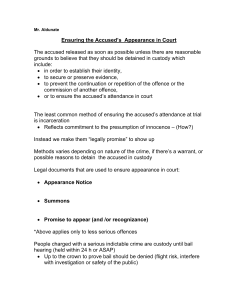

Ratio/importance of case issue case main Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 8 I. 2. R. v. Dudley and Stephens (1884) UK: no defence of necessity recognized ................................... 8 Sources of Criminal Law ........................................................................................................................ 9 A. Common Law .................................................................................................................................. 10 Offence Definition .............................................................................................................................. 10 I. R. v. Sedley (1727): [before written Code, misdemeanors against King’s peace] ........................ 10 The Criminal Code (Statute) ............................................................................................................... 10 II. Frey v. Fedoruk (1950) SCC – [illegal arrest of peeping tom because code in effect in which peeping not an offence] ......................................................................................................................... 11 Doctrine of precedent ........................................................................................................................ 12 I. R. v. Henry (2005) [SCC commenting on the oversimplification between the narrower ratio decidendi which is binding and obiter, which may safely be ignore] ................................................... 12 B. Statutes ........................................................................................................................................... 13 I. R. v. Clark (2005) [example of statutory interpretation of word public place in the offence, masturbating guy in window]: ................................................................................................................... 13 Bilingual interpretation ...................................................................................................................... 14 Strict construction .............................................................................................................................. 14 I. R. v. Paré (1987) [defendant assaults boy then kills boy after a moment of contemplation; no strict construction, murder happened while in act so first-degree] .................................................... 15 Criminology......................................................................................................................................... 16 Punishment and Deterrence: ............................................................................................................. 16 Doob Webster – Sentence Severity and Crime: Accepting the Null Hypothesis .............................. 16 C. Constitution as source of Criminal Law .......................................................................................... 17 Divisions of Powers ............................................................................................................................ 17 Charter of Rights and Freedoms ........................................................................................................ 18 I. Hunter v. Southam Inc. [1984] – purposive approach to interpretation of any provision of Charter .................................................................................................................................................... 18 Section 7 & Principles of Fundamental Justice.................................................................................. 18 I. Canadian foundation for children, youth and the law v. Canada (Attorney General) [2004] – law being vague test – the Spanking case – [child abuse Criminal Code defense] ..................................... 19 1 Ratio/importance of case issue case main II. Bedford v. Canada (Attorney General) [2013] – Section 7’s violation in the sense of the security of the sex workers. Criminal offences that were challenged infringe on the security of person. ...... 21 III. R. v. Safarzadeh- Markhali [2016] – on overbreadth, gross proportionality and arbitrariness 23 IV. R. v. Oakes [1986] – Oakes test to save limits on Charter rights .............................................. 24 Comparing section 7 and section 1 (Bedford): .................................................................................. 24 3. The Criminal Process ........................................................................................................................... 25 A. Procedural Overview....................................................................................................................... 25 Procedural Classification of Offences ................................................................................................ 25 Offences triable only on indictment .................................................................................................. 26 Summary conviction offences ............................................................................................................ 26 Crown election offences (dual, hybrid) ............................................................................................. 26 B. Presumption of innocence .............................................................................................................. 29 I. Woolmington v. D.P.P [1935] – accused presumed innocent until proven guilty; case about guy accidentally shooting his wife to death ................................................................................................. 29 C. Reasonable Doubt ........................................................................................................................... 30 I. R. v. Lifchus [1997] – leading case on explaining proof beyond a reasonable doubt to jury – to be explained in every criminal case ....................................................................................................... 30 II. R. v. Starr [2000] – confirming a lot of the points on proof beyond reasonable doubt from Lifchus – explained in every criminal case ............................................................................................ 31 III. R. v. S. (J.H) [2008] – special case of explaining reasonable doubt to jury in credibility contest cases (he said-she said) .......................................................................................................................... 31 Section 11(d) of the Charter ............................................................................................................... 32 IV. R. v. Oakes [1986] SCC – “reverse onus” burden of proof put on defense by legislation violates s.11(d). ...................................................................................................................................... 32 D. Victims’ Rights ................................................................................................................................. 33 E. Scope of the Criminal Law............................................................................................................... 34 I. R. v. Malmo-Levine [2003] – harm principle not a PFJ – how to classify PFJ ............................... 35 F. Adversary System ............................................................................................................................ 36 Steve Coughlan, “The ‘Adversary System’: Rhetoric or Reality” [1993] .......................................... 37 Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Portia in a Different Voice: Speculation on a Women’s Lawyering Process [1985] .................................................................................................................................................. 37 Madam Justice Bertha Wilson, Will Women Judges Really Make a Difference? [1990] ................. 38 Aboriginal Peoples and Criminal Justice – Law Reform Commission of Canada [1991] .................. 38 Rupert Ross, Dancing with a Ghost.................................................................................................... 39 2 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Honoring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future [2015] .................................................................... 39 I. R. v. R.D.S [1997] – Reasonable Apprehension of bias test – whether judges should bring context/personal values to judgements ............................................................................................... 40 G. Sentencing Principles ...................................................................................................................... 42 H. Aboriginal Sentencing ..................................................................................................................... 43 I. R v. Gladue [1999] – interpretation of s. 718.2(e) for Aboriginal ................................................. 43 II. R v. Ipeelee [2012] – Aboriginal sentencing .................................................................................. 44 I. Ethics of Crown and Defense .......................................................................................................... 44 4. The Act Requirement .......................................................................................................................... 45 1) Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 45 2) Consent making act lawful .............................................................................................................. 46 I. R v. Jobidon [1991] – FIST FIGHT!! consent vitiated by common law limits – assault without consent – no consent to death – culpable homicide ............................................................................. 46 II. R. v. Cuerrier ([998] – HIV case – consent to sexual activity vitiated – aggravated assault – Cuerrier test of “bodily harm” ............................................................................................................... 48 III. R. v. Mabior [2012] – no assault because HIV guy used protection and had treatment aggravated sexual assault in Code ........................................................................................................ 49 IV. R. v. Hutchinson [2014] – consent in code – woman agrees to sex ONLY WITH CONDOM – guy pokes holes in condom – girl pregnant.................................................................................................. 50 3) Omissions ........................................................................................................................................ 52 I. Buch v. Amory Mortgage Co. [1898] – law’s individualistic approach to defining when there is a legal duty to act...................................................................................................................................... 52 Legal Duties found in the Code .......................................................................................................... 52 Liability for Omissions – Requirements: ............................................................................................ 53 II. R v. Browne [1997] – girl swallowed cocaine and her partner calls taxi instead of ambulance to take her to hospital – no undertaking [defined here] of a legal duty so not guilty............................... 53 III. R v. Peterson [2005] – legal duty to person under your charge (such as an elderly parent) ..... 54 4) Voluntariness .................................................................................................................................. 55 I. R. v. Lucki [1955] – acquittal for involuntary act of slipping on black ice ...................................... 56 II. R. v. Wolfe [1975] – reflex actions also involuntary – guy hits with a telephone .......................... 57 III. R. v. Swaby [2001] – guy driving unaware that passenger in his car has an unlicensed gun .... 57 IV. Kilbride v. Lake - This case an example of an involuntary OMISSION (because failure to have the warrant). ........................................................................................................................................... 58 5) Causation ........................................................................................................................................ 58 3 Ratio/importance of case issue case main I. R. v. Smithers [1978] SCC – leading case on causation test (significant contributing factor outside the de minimis range) ............................................................................................................................. 59 II. R. v. Harbottle 1993 – test for causation for 1ST degree murder: “substantial cause test” – ONLY FOR MURDER(sexual assault) ................................................................................................................. 60 III. R. v. Nette 2001 – significant contributing cause test: FOR ALL CAUSATION IN CRIM – START WITH THIS TEST FOR HOMICIDE BEFORE GOING TO HARBOTTLE TEST ................................................ 61 Intervening Cause:.............................................................................................................................. 62 The Code: Causation in Homicide: ..................................................................................................... 62 I. R. v. Smith [1959] – English case about intervening cause ........................................................... 63 II. R. v. Blaue [1975] English case – woman refusing blood transfusion and bleeds out because of wound ..................................................................................................................................................... 64 III. 5. R. v. Maybin – FIRST CASE TO GO TO FOR INTERVENING CAUSE ANALYTICAL AIDS ............... 64 The Fault Requirement ....................................................................................................................... 66 1) Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 66 I. R. v. Beaver [1957] – KNOWLEDGE required for subjective mens rea – guy had cocaine but thought it was powdered sugar............................................................................................................. 67 2) Regulatory offences ........................................................................................................................ 68 I. R. v. City of Sault Ste. Marie [1978] – strict liability fault for regulatory offenses ..................... 68 II. R. v. Wholesale Travel Group Inc. – difference between regulatory and criminal offences ........ 69 Charter Standards for Fault:............................................................................................................... 69 III. Levis v. Tetreault – due diligence can’t be passive – need to take reasonable precautions ... 70 3) Murder ............................................................................................................................................ 70 I. The Simpson Case [1981] – jury instruction for PROPERLY instructing jury on subjective intent for murder (s.229(a) & (b)) ..................................................................................................................... 71 II. R. v. Edelenbos [2004] – no need to give definition of likely – be careful in language used for SUBJECTIVE FAULT (has to include knowledge AND INTENT) ............................................................... 71 Constructive murder .......................................................................................................................... 72 I. Vaillancourt v. R [1987] – murder under constitution requires at least objective foresight ....... 72 II. R. v. Martineau [1990] – constructive murder – ALL OF S.230 UNCONSTITUTIONAL – s.7 of Charter requires subjective, not objective foresight of death to be guilty of murder ......................... 73 Degrees of Murder: ............................................................................................................................ 74 I. R. v. Smith [1979] – leading case for test for planned and deliberate murder: ........................... 75 II. R. v. Nygaard and Schimmens [1989]: - 1st degree murder if bodily harm LIKELY causing death, even if not intending death .................................................................................................................... 75 III. R. v. Collins [1989] – murder of police officers on duty ............................................................. 75 4 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 4) Subjective mens rea ........................................................................................................................ 76 I. R. v. H. (A.D) [2013] – child abandonment code provision, Walmart washroom ........................ 77 II. R. v. Buzzanga & Durocher [1979] – definition of intent as conscious purpose or foresight of prohibited consequence. ........................................................................................................................ 77 III. Sansregret v. R [1985] – definition of recklessness as a subjective fault ................................. 78 IV. R. v. Briscoe [2010] ..................................................................................................................... 78 V. R. v. Blondin [1971] – willful blindness .......................................................................................... 79 5) Objective Fault ................................................................................................................................ 79 Criminal negligence ............................................................................................................................ 80 I. O’Grady v. Sparling [1960] -criminal negligence historically subjective fault ............................. 80 II. R. v. Tutton & Tutton [1989] – discussion of when to use objective vs. subjective fault ............. 80 III. R v. Creighton [1993] – objective standard requires marked departure from SOC ................. 82 IV. R. v. Beaty [2008] -negligent driving in torts but not criminal negligence if no “marked departure” from SOC of dangerous driving........................................................................................... 83 V. R. F (J) [2008] -difference between “marked & substantial departure” vs. “marked departure” 84 Unlawful act manslaughter (UAM) .................................................................................................... 84 I. R. v. Creighton [1993] – leading case on UAM and test for it. ..................................................... 85 Aggravated forms of assault .............................................................................................................. 85 6. Rape and Sexual Assault ..................................................................................................................... 86 1) Rape laws in context – historical rules around rape, granted spousal immunity (yuck) ................ 86 2) Crimes of sexual assault .................................................................................................................. 88 I. 3) R. v. Chase [1987] – leading case for definition of sexual assault ............................................ 88 Consent and mistaken belief .......................................................................................................... 88 I. R. v. Ewanchuk [1999] – meaning of consent, no such thing as implied consent, fear may result in compliance but there still can be no consent so no need to look at vitiation .................... 89 II. 7. R. v. A. (J) [2011] – consent in advance for sexual activities, esp. if unconscious? .................. 91 Incapacity ............................................................................................................................................ 92 1) Age .................................................................................................................................................. 92 2) Mental disorder .............................................................................................................................. 92 I. Cooper v. R. [1979] – leading case on defense of MENTAL DISORDER, disease of mind definition 93 3) Automatism..................................................................................................................................... 94 5 Ratio/importance of case issue case main I. Rabey v. R [1977] – anger/rage/psychological blow not analogous to external cause of automatism of a blow to head – psychological blow must be in extraordinary events to be automatism ............................................................................................................................................ 94 II. R. v. Parks [1992] – OVERTURNED BY STONE – sleepwalking, acquitted under sane automatism 95 III. R. v. Stone [1999] – START WITH THIS CASE WHEN DEALING WITH AUTOMATISM – presumption of automatism as MDA .................................................................................................... 96 IV. 4) R. v. Luedecke [2008] – sexsomnia guy – how to respond to automatism claims ................... 98 Intoxication ..................................................................................................................................... 99 I. R. v. Daviault (1994, SCC) – extreme drunkenness is defense for general intent offences; later removed by Parliament for violent crimes, Charter Minimum ....................................................... 100 II. R. v. Jensen – constitutionality of s.33.1 for being valid as limiting extreme intoxication defense to only non-violent offences with general intent ................................................................................ 101 III. 8. R. v. Daley [2007] – 3 INTOXICATION DEFENSES – START WITH ADVANCED INTOXICATION 102 Justifications and Excuses ................................................................................................................. 103 1) Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 104 I. 2) R. v. Cinous [2002] – “Air of reality” test for ALL Defenses ..................................................... 104 Defense of person ......................................................................................................................... 104 I. R. v. Lavallee [1990] – self-defense by woman in an abusive relationship - battered woman syndrome .......................................................................................................................................... 106 II. R. v. Malott – “battered women” syndrome not a defense in itself – rather, allows for expert evidence to be used for accused women in abusive relationships ................................................. 107 III. Cormier v. R. [2017] – acting in defense of property can also result in defense of person 107 POLICY ON SELF-DEFENSE .................................................................................................................... 108 3) Defense of property ...................................................................................................................... 108 4) Necessity ....................................................................................................................................... 109 I. R. v. Dudley and Stephens (1884) UK: no defense of necessity recognized to kill a life for food 109 II. R. v. Perka [1984] – necessity accepted as an excuse, not justification – 3 PART TEST FOR USING THIS DEFENSE ........................................................................................................................ 111 III. 5) R. v. Latimer [2001] – further interpretation of the PERKA 3-PART TEST for NECESSITY:.. 112 Duress ........................................................................................................................................... 113 I. R. v. Paquette [1977] – s.17 limitations on defense of duress only apply to principle offenders, not aiders/abettors ........................................................................................................ 113 II. R. v. Hibbert [1995] – common law duress defense requires “no safe avenue of escape”.... 115 6 Ratio/importance of case issue case main III. R. v. Ruzic [2001] – reads out immediacy and presence requirement from s.17 defense of duress due to Charter: ...................................................................................................................... 115 IV. R. v. Ryan – 7 requirements for statutory defense of duress vs 6 requirements for common law duress defense: .......................................................................................................................... 115 6) Provocation ................................................................................................................................... 117 I. R. v. Tran – ELEMENTS OF PROVOCATION DEFENSE ............................................................... 118 II. R. v. Hill – who is the ordinary person who is provoked: ........................................................ 119 7 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 1. Introduction Criminal law: about extremely offending behavior in society so that it is punishable by law. Situations like individuals have been murdered, sexual assault, robbery etc. Criminal Code first enacted in 1892 – applies federally except in NWT and Yukon. Jury Trials: Trier of law vs. fact Trier of law Decides what the law is, explains it to the jury and then the trier of fact applies it. In a jury case, it is the judge. In a judge case, it’s the judge Basically, judge always the trier of law Trier of fact Decides the facts and apply the law and come up with a verdict. In a jury case, it is the jury. In a judge case, it is also the judge Example of criminal case for a source of criminal law: I. Facts: Issue: R. v. Dudley and Stephens (1884) UK: no defence of necessity recognized Guys on boat stranded; starving; finally decide to kill and eat a boy A special verdict case in which jury from lower court asked to give facts and then referenced to a higher court. D & S charged with murder of cabin boy Richard Parker, after they were cast away on a lifeboat and lost at sea They run out of food and on the verge of death after 3 weeks of being lost Richard Parker had fallen sick from drinking sea water, so perhaps he would have died anyway D & S decide the boy should be killed so the rest can survive (third guy Brooks dissent) The boy did not consent to being killed or eaten Dudley committed the act of killing; all three ate the boy 4 days later they are rescued, even though there wasn’t any reasonable expectation of them being rescued If they hadn’t killed and eaten the boy, they probably would have died by the time they were rescued. D & S charged with murder for killing Richard Parker Brooks not charged because he dissented, did not want to kill and definitely did not participate in the act (he did eat the boy, which is a moral issue and a different offence than what’s being discussed here) Is necessity a defence for murder for your own survival, especially when the other person has not provoked aggression? Can murder be justified out of desperation to save one’s own life? 8 Ratio/importance of case issue Ratio: case main Necessity is not a defence to murder (broadly) Taking the life away of a person when they haven’t provoked aggression is not a defence (narrow) Reasons: Notes: Lord Coleridge: Dangerous precedent if acquitted because it would open the floodgates by allowing murder to always be justified in some broad way While not every immoral act is illegal, need to be careful on how much to divorce morality from legality and inappropriate to do so in this case because if we allow defence by accused of “temptation” to murder, then there would be fatal consequences...murder is immoral and that shouldn’t be divorced from the law. Who decides how we value one life more than another? Who decides whose necessity is more important and thus grants them survival than another person [ex: they decided to kill the boy because he was already dying – well, why not kill Brooks?] What if Richard Parker had consented? What if straws had been drawn to decide who dies – maybe this is fairer but what is real consent? D & S guilty of murder but consider context for deciding appropriate sentencing Charged with capitol punishment but Queen Victoria eventually brought down the charges to 6 months in jail Law showing its hard-core approach to maintaining morality of certain acts but at the same time taking context into consideration for sentencing Not in this case, but perhaps in other cases necessity could be a defence? Ex: conjunct twins who share a heart and both are dying unless surgery is performed to move the heart completely to one body, in which case one would have to die. 2. Sources of Criminal Law 1. Constitution Most fundamental law of the nation All other laws are dependent on the constitution The constitution gives the parliament the right to makes law It defines the exercise of state authority All other laws conform to the constitution 2. Statutes (legislation) Example: criminal code is a federal statute which is applied throughout Canada Statutes take precedent over common law 3. Common law 9 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Principles found in cases that become part of the common law (example, the necessity principle from Dudley and Stephens) Cases can lay out principles but parliament can overrule by making new statute. A. Common Law Offence Definition I. Historically, open to judges to convict people of immoral offences, even if no written code was violated Judges had power to decide what was a crime as a matter of common law – still prevalent in England to this date. Offences were determined as such because they were laid out in other cases, or if there was no other case, judge could just make it a new offence Vague because how is a person supposed to know what an offense is if the judges declare AFTER the fact that it is actually an offence? Makes it open ended for judges to decide No checks and balances so problematic for rule of law R. v. Sedley (1727): [before written Code, misdemeanors against King’s peace] Facts: Issue: Ratio: Reasons: Sir Charles Sedley drunk and naked in a balcony in Covent Garden Swearing and throwing bottles of urine down into the square where other people present Charged with misdemeanors against the King’s peace (awfully broad) Should the judge convict Sedley for a conduct previously not recognized as a crime? Was guilty of misdemeanor against the King’s peace It was high time to punish this kind of immoral behavior – judge could make new offences under common law at this time The Criminal Code (Statute) After the criminal code was enacted in Canada, is it still open for judges to decide on a case for which there is no offence included in the criminal code? Declares offences, defenses and procedure Didn’t need to go to old cases anymore to find out what was an offence Question became, is it still open to judges to punish someone for an offence if it wasn’t found in Code Provincial offences declared in provincial statutes/regulations 10 Ratio/importance of case issue II. Issue: Decision: Reasons: Notes: main Frey v. Fedoruk (1950) SCC – [illegal arrest of peeping tom because code in effect in which peeping not an offence] Facts: Ratio: case Frey was a peeping tom through Fedoruk’s window at his mother Fedoruk chased Frey with a butcher’s knife and detained him Stone, a police officer, was called and he arrested Frey without a warrant Frey sued Fredourk and police officer on the basis that neither of them was legally allowed to detain or arrest him Did Frey commit an offence by peeping at Fredoruk’s mom, because if so, they were warranted to arrest him? Frey’s behavior did not warrant an arrest because it was not an offence. Judge Cartwright: There was no peeping offence in the Criminal Code at the time, nor was it an established common law offence. If something is not already a crime, either in the Criminal Code or common law, then it is not up to the courts to define whether it is a crime (that’s up to parliament to decide) put a stop to what happened to Sedley; something has to already be an offence at the time the person does it From now on (1950), no new common law offences – only offences created by Statute in the Follow up to this case an amendment to the Code where no person can be convicted by an offense at the common law, no old or new ones either. Only a criminal offence if in the Code. Only common law offence: contempt of court Policy implications of crimes determined by statute: Pros: Citizens know in advance whether something an offence Clarifies roe of judges – they can’t just create criminal offences based on individual cases Protection of citizen’s civil liabilities – can govern behavior according to provisions that are clearly laid out Cons: Statutes take a long time to pass – by the time something actually becomes an offence through statute, a lot of people may already have been wronged Statues are open to political debating/tricks like getting votes Parts of Canadian criminal law found in common law cases: Not offences (these MUST BE in statutes) Some defenses exist only in the common law (e.g. necessity) Often fault element for an offense is found in the common law (where the statute is silent) Your mental state Many other important criminal law principles based on common law 11 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Doctrine of precedent I. Common law develops through precedent Principles from past cases become law and govern the way future cases are decided they come binding common law rules Whether a statement in a case is binding depends on three things: i. Which court made the statement? Higher court’s decision binding on lower courts SCC highest court in Canada so binding on all courts in Canada its own precedents binding on itself Ontario Court of Appeal rulings binding on all courts within Ontario (not on lower courts of other provinces) Trial court rulings and rulings from other provincial courts of appeals just persuasive, not binding Scholarly articles, judgements from foreign courts also persuasive (but generally less so) ii. In which judgement was the statement made? Appeal courts have panels of judges and can issue: Unanimous judgements (binding…most precedent value) Majority judgements (also binding) Dissenting judgements Concurring judgements (reached same conclusion as majority but through different reasoning) iii. Which parts of the judgement is actually binding? Binding precedent on the points a case stands for – what was the point of law that was being decided Stare decisis – to stand by what is decided. The basic principle that precedent governs in the common law that like cases should be decided alike Ratio decidendi – the reasons for the decision (the points the case actually decides and thus is binding on lower courts) Obiter dictum – not binding – are things/remarks said in the course of a judgement that are not essential to resolve the dispute R. v. Henry (2005) [SCC commenting on the oversimplification between the narrower ratio decidendi which is binding and obiter, which may safely be ignore] Judge Binnie highlights two EXTREME and wrong approaches to binding statements: Traditional view as expressed by Earl of Halsbury: “a case is only an authority for what it actually decides” A very narrow view and following cases need to be very similar on facts or You apply the broad Sellers test from Sellars v. The Queen Very broad application in that all SCC’s decisions are binding Problematic because would deprive lower courts of creative thought and reasoning in applying law, especially in novel contexts and to foster growth of jurisprudence. 12 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Ratio is binding for sure which is bound by facts However, additional analysis intended for guidance, which should be accepted as authoritative In R. v. Oakes for example, the ratio was that there was no connection between possession of narcotics and legislated presumption that the possession was for the purpose of trafficking However, the C.J Dickson provided a very broad purposive analysis of s. 1 of the Charter in coming up to this decision, which was intended to and has been binding on other courts Point of law is not to stifle growth by taking an extreme broad/narrow approach; but rather to foster certainty of the law. Parts from obiter such as Oakes analysis can become binding Over time, you just get very distinct cases coming out of the common law due to distinguishing factors from one case to another and lawyers often look to those fine distinguishing points to argue how precedent may or may not be differently applied for their client. B. Statutes I. Judges interpret what the language of a statute means Not discretionary interpretation; statute needs to be read in their “context, grammatical and ordinary sense, harmoniously with the schemes and objectives of the act and the intention of the parliament in enacting the act.” Iacobucci and Arbour JJ. Legislation needs to be consistent with the constitution and charter – so if two interpretations and of them goes against charter, you discard that. No binding rule of law that statute must be read in grammatical sense; sometimes, reading at face value does not make sense. R. v. Clark (2005) [example of statutory interpretation of word public place in the offence, masturbating guy in window]: Code offences: Facts: s. 150: In this part…” public place includes any place to which the public have access as of right or by invitation, expressed or implied” s. 173 (1). Everyone who willfully does an indecent act a). in a public place in the presence of one or more persons, or b). in any place, with intent thereby to insult or offend any person, is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction. Clark masturbating near an uncovered window in his illuminated living room Noticed by Mrs. S, a neighbor, and her husband who call the police. Police charges Mr. Clark under s. 173(1)(a) and s. 173(1)(b). Trial judge: C didn't know anyone was watching and so couldn't be convicted under second provision, because no intent; but did convict under first provision Court of Appeal B.C confirmed Clark’s conviction under first provision 13 Ratio/importance of case issue main Issue: Decision: Reason: Ratio: Notes: case C appealed to SCC Was Clarks’ living room a public place, as defined by s.150? Was Mrs. S in Clark’s presence while she was watching from her own bedroom? Clark acquitted J. Fish: Applied statutory interpretation to the meaning of the word “public place” in s.150, which he interpreted to only mean physical access, as opposed to peering [visual access] into a place like Mrs. S did. If we allow visual sight as access, it would be too broad Public place means you have to have physical access SCC deals with how Court of Appeal departs from the factual findings of trial judge – which can be allowed if there is a great error but in this case it was uncalled for Justification for this is that trial judge heard evidence, testimonies etc. so more thorough at establishing facts; also to prevent appeals on establishing facts over and over again. Bilingual interpretation In Canada, all statute law (even provincial) is passed in both official languages: English and French. Both versions are authoritative. The aim of the legislation is to express the same meaning in both languages However, often hard to establish the same meaning because of translation Where the meaning is unclear in one language but clear in the other, the interpretation common to both language is preferred (because remember, both languages are authoritative). When one interpretation broad and the other restricted, latter favored more Strict construction Only applies to criminal cases and only when there is still ambiguity after context has been considered. If defense asks for strict construction to be applied in a trial, crown can reject it on the basis that the statute only has one interpretation that favors crown, not defendant “A rule of statutory construction that if a penal provision is reasonably capable of two interpretations that interpretation which the more favorable to the accused must adopted.” R. v. Goulis, per Martin J.A. Strict construction also applies to facts – that if there is doubt about facts, it should favor the accused and give him the benefit of the doubt Policy reasons for 2 possible interpretations of statutes: State exercises great power over an accused’s rights so should only be allowed to infringe on those liberties when we’re absolutely sure that’s what parliament intend Also, important to really be clear whether behavior is criminal or not and not leave any ambiguity so that general public has proper notice of what is criminal behavior and not. 14 Ratio/importance of case issue I. case main R. v. Paré (1987) [defendant assaults boy then kills boy after a moment of contemplation; no strict construction, murder happened while in act so first-degree] Code Provisions: Facts: Issue: Decision: Reasons: Ratio: s. 231(5) “murder is first degree murder…when the death is caused…while committing” a sexual assault. [previously s.214(5)] Accused, 17 yo, lured a 7 yo boy under a bridge and sexually assaulted the boy Boy threatened to tell his mom; accused threatened to kill him Accused hel boy down for a few minutes; then strangled him and hit him on head with oil filter Accused charged with first degree murder according to s.231(5). Dispute whether this is first degree or second-degree murder (would impact sentencing) based on the while committing part Defence argues that strict construction doctrine should apply to defendant because due to ambiguity on whether murder committed while committing sexual assault or not; defense argues the assault had already happened so strict construct Did the defendant commit the murder while committing the assault? Does the doctrine of strict construction apply to the phrase “while committing?” 1st degree murder conviction restored. J. Wilson: Strict construction does not apply because there is only one interpretation If parliament had intended that first-degree requires simultaneous acts, how do you delineate the two? How do you determine when the sexual act ended (was it when he was putting his pants back on because he still had his hand on top of the kid so maybe that was still assault) Irrational to say crime less severe because accused waited a few minutes before strangling – the fact he had moments of deliberation makes it more severe rather Justice Martin’s single transaction approach to define while committing as “when the act causing death and the acts constituting the rape/attempted rape/assault/etc. all form part of one continuous sequence of events, forming a single transaction" so part of one continuous sequence of events. Court clearly recognizes that principle of strict construction does exist, but they don't apply it to this case because there aren't 2 reasonable interpretations that exist Limits on the value of codification In theory, the criminal code should give some clear structure to criminal law. 15 Ratio/importance of case issue case main In reality, Canada’s criminal code does not have a logical structure and is not always consistent or coherent. There is no ‘general part’ jurisdictional rules for which court tries which offense Principles of fault are not articulated clearly or consistently Various provisions and offences in the Code should be removed: Obsolete offences (like publishing crime comics) Provisions that have been “struck down” as unconstitutional Criminology the study of crime as a social phenomenon for example, the causes, nature, punishment or treatment of criminal behavior criminology has many finding relevant to how we organize criminal law and statutes: crime is heterogenous it is very broad (ex: dangerous driving, tax evasion, killing someone in a fight) so what do all these have common that makes them criminal? The fact that all these are considered bad behavior so offensive to society that they should be punishable by law. But this is very broadly defined crimes causes are complex (biological, social, psychological factors etc.) there aren’t simple reasons like poverty rates of reoffending are high, regardless of treatment or punishment future dangerousness is difficult to predict Punishment and Deterrence: Deterrence: Prevention by fear of the consequences Criminal punishment can be directed at: Specific deterrence (of the specific offender) General deterrence (of others in the community who know the offender will be deterred by seeing how the offender ended up in jail and just general public) Deterrent effect of punishment might vary with: The nature of the offense (dangerous driving vs. murder) Probability of being punished (ex: driving on a super isolated road vs. on a major highway where traffic police are common) Severity of punishment Does imposing harsher sentences reduce crime? Generally, no. Doob Webster – Sentence Severity and Crime: Accepting the Null Hypothesis “The hypothesis that harsher sentences would reduce crime through general deterrence – which is to say that there are marginal effects of general deterrence – is not supported by the research literature. Marginal deterrence – the effect of changing the severity of the punishment and they say that it makes no difference. 16 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Deterrence probably works better for certain offences compared to others – i.e. Crimes like murder happen in the heat of the moment, not really thinking through consequences of their actions For harsher sentences to have effect, people would need to first believe it would be reasonable that they would be caught; be aware of harsher sentence; consider consequence when deciding to commit offence; be willing to commit offence for a lesser punishment but not for an increased, harsher one Increasing sentence severity gives false hope to the public that we'll reduce incidence of crime C. Constitution as source of Criminal Law Constitution Act 1867 is the most fundamental law of Canada and it lays down the exercise of state authority and organs of the state. 2 basic topics in constitution law: Divisions of Powers Federalism: Division of legislative power in s. 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act and which of the 2 levels of govt. can create law in particular areas. Fed. Parliament has criminal law-making and procedure making power under s.91 (27) of the Constitution Act 1867 – “The criminal law…including procedure in criminal matter.” Substantive criminal law: deciding what counts as offence and defence, what are blameworthy acts punishable under law Criminal Procedure: how to run a recognized offence through the court system, including matters of charging, arrest, detention and bail, trial procedure, sentencing, appeals etc. Criminal Code a federal statute that applies across all provinces Provinces still have some rights to give rise to offences, as contained in the Const. Act 1867: S. 92 (15) – the imposition of punishment by fine, penalty, or imprisonment for enforcing any law of the province…” (so for stuff like traffic regulations) Not criminal offences but offences you could still go to jail for violating provincial legislation laws. Ex: speeding offences are regulatory offences, not criminal offences. Other powers relevant to criminal law: Federal power over penitentiaries – s91(28) Const. Act 1867 If sentence is more than 2 years, it’s in a federal penitentiary. Provincial power over provincial jails – s92(6) Const. Act 1867 If sentencing less than 2 years, then provincial jail. Provincial power over provincial courts – 92(4) Const. Act 1867 Provincial govt. runs the criminal show from bottom to top but federal govt. has jurisdiction over enacting legislation for criminal matters. 17 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Charter of Rights and Freedoms I. The bill of rights and the limits it puts onto the criminal law. Const. Act 1982 has supremacy law in s.52(1) that constitution is at the top of the law 3o% of language of Charter related to criminal offences Charter puts limits on substantive crim. Law of Canada Charter limits legislative power of Canadian parliament and prov. Legislatures Constitution like a “living tree” so broad interpretation as it evolves over time Constitution not subject to same interpretive techniques used for statute interpretation. Some sections affect substantive law (s. 1 and 7 of charter) Hunter v. Southam Inc. [1984] – purposive approach to interpretation of any provision of Charter A case that tried to find the underlying purpose of the constitution to be broad and evolving “judiciary are the guardians of the constitution Not to be interpreted in the same sense as statutes. In this specific case of wrongful search and seizure, purposive approach applied to s. 8 of charter – which was found to be to protect privacy and thus require police to obtain a search warrant signed off by search to search. Section 7 & Principles of Fundamental Justice Focused on two provisions of the Charter that have implications on substantive criminal law: S. 1 (limitation clause): the rights set out in the charter are not unlimited but can be subject to limitation by the govt. provided they are prescribed by the law and are demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. S. 7: “everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance the principles of fundamental justice” Violation of s. 7 requires BOTH: Deprivation of either life, liberty or security of the person any offence that carries sentencing in prison means denying liberty of a person and thus violation of s.7 HOWEVER Liberty is limited, and state can take away liberty for criminal offence but just have to be in a way that adheres to the principles of fundamental justice (PFJ) [If you’re fair in taking away the liberty in accordance to the PFJ then compliance to s.7 achieved] Violation of the principles of fundamental justice 18 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Principles of fundamental justice (PFJ): legal principle attained through social consensus on how legal system should work and should have sufficient legal precision. A lot of principles of fundamental justice are procedural (e.g. right to fair trial) But SCC said there are also substantive rules of what kinds of conduct can be defined as an offence (put limits on what Parliament is actually allowed to define as an offence) 4 substantive law principles of fundamental justice that put limits on criminal law Criminal law may not be too vague (unclear, imprecise) i.e. See Sedley case (misdemeanors against King’s peace) Criminal law may not be overly-broad - too wide or expansive (some conduct may appropriately be in rule, but law goes too far in criminalizing behavior) Criminal law may not be arbitrary - unfixed or unprincipled Criminal law may not be grossly disproportionate I. Canadian foundation for children, youth and the law v. Canada (Attorney General) [2004] – law being vague test – the Spanking case – [child abuse Criminal Code defense] Criminal Code provision: Facts: Issues: Decision: Reasons: s. 43: “Every schoolteacher, parent or person standing in the place of a parent is justified in using force by way of correction toward a pupil or child, as the case may be, who is under his care, if the force does not exceed what is reasonable under the circumstance.” Sort of like defense to child abuse? The CFCYL challenged the law for violating the FPJ that a law cannot be vague. Is s.43 too vague? Does it delineate a risk zone for criminal sanction? s.43 does delineate such a risk zone and thus not a vague law. McLachlin J (majority): Applies the vagueness test saying that law must delineate a risk zone for criminal sanction – some ambiguity is acceptable Law sets forth who can enter sphere where there is no criminal sanction (parent, teacher, etc.) and what conduct falls within sphere (pulls out implicit limitations through statutory interpretation): Force needs to be for purpose of correction of child’s behavior Has to be sober, reasoned use of forces that addresses child’s behavior, not out of rage or violence Aimed towards educating or disciplining the child Infants and toddlers under the age of 2 can’t understand why they’re being spanked, and other children who are older with certain disabilities may not be able to be corrected by use of force thus can’t use corporal punishment on these groups Force needs to be reasonable under the circumstances Minor corrective force of a transitory or trifling nature Unreasonable uses of force: beating a child, degrading or demeaning treatment, use of belts, blows to the head, use by teachers, punishment of kids under 2 or teens, severe punishment in any situation (no matter how bad the child’s behavior) Arbour J. (dissenting): Terrible frank child abuse cases excused under s.43 19 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Past judges of Canada have not been able to use it in a reasonable way in the past so you can’t be persuasive by coming up with a list on your own setting the limits on the statute is this list even exhaustive? Furthermore, it’s not even the job of the judiciary to do that but rather of the legislation to decide the limits. Reasonableness is an acceptable criterion in some criminal law contexts but here it has no clear meaning (ex: self-defense in a situation where you’re being attacked is reasonable and proportional to the assault but not to a child) To find the provision is not vague, the majority in this decision the rewrites the statute which is beyond the limits of statutory interpretation. Ratio: Notes: Test for vagueness: whether the law delineates a risk zone for criminal sanction. McLachlin discusses POLICY reasons why we need to make sure laws are not too vague Notice to the citizen - people are supposed to know in advance when they might come into conflict with the criminal law Discretionary enforcement problem: leaving too much to discretion of law enforcement officials if law is too vague and up to them to decide when to charge (citz subject to rule of law, not rule of persons) McLachlin’s decision is criticized for being overly enthusiastic in interpretation The leading case (Bedford) for the following three principles of fundamental justice: A criminal law may not be overly broad Can’t have a criminal law that goes beyond what is acceptably considered criminal Ex: Haywood case: a law that give automatic life prohibition on sex offender to loiter in a park. Some application of this law makes sense where the offender might be taking pictures of children But at the same time, the ‘for life’ term was considered overly broad A criminal law may not arbitrary Something is arbitrary when it’s not based on some legitimate principle and instead based on the whim of a decision maker A criminal law may not be grossly disproportionate. Refers to the fact that sometimes even if it is acceptable sometimes to punish someone, some punishments can be way too harsh Ex in the Bedford case: you can have a law against spitting on the sidewalk but life sentence for that would be grossly disproportionate. 20 Ratio/importance of case issue II. case main Bedford v. Canada (Attorney General) [2013] – Section 7’s violation in the sense of the security of the sex workers. Criminal offences that were challenged infringe on the security of person. Criminal Code Provisions challenged: Facts: Issue: Decision: Reasons: S. 210: prohibiting operating common bawdy-houses S. 212(1)(j): living on the avails of prostitution S.213(1)(c): communicating for the purpose of prostitution. Applicant challenged these provisions, arguing they violated their s.7 Charter “rights to life, liberty and security of the person…”by putting safety of prostitutes at risk and preventing them from implementing safety measures for themselves Challenge to the constitutionality of the above provisions, pursuant to s.7 of the Charter Do these Criminal Code provisions violate s.7? Unanimous SCC decision to strike down all three laws. all 3 provisions inconsistent with s.7 because they deprive security of the person of prostitutes. Deprivation is grossly disproportionate re: s.210 and s.213(1)(c) and overbroad re: s. 212(1)(j). Cannot be saved under s1. Reasons: McLachlin (Court) Prostitution itself is a legal activity, and these 3 provisions imposed dangerous conditions by preventing individuals engaged in this activity from taking steps to protect themselves from risk -- effect of making a lawful activity more dangerous All 3 principles are “failures of instrumental rationality” – law is inadequately connected to its objective or goes too far to seek those objectives Rules: o Arbitrariness: asks if there is a direct connection between the purpose of the law and the effect on individuals A law is arbitrary when it limits s7 rights in a way that bears no connection to the objective of the law **Comparing objective of law to negative effect on s7 rights Don't look at how effective the law is in achieving the objective o Overbreadth: where law is so broad that it includes some conduct that has no relation to purpose (arbitrary in part) A law is overly broad where there is rational connection btw the purposes of the law and some, but not all, of its impacts (law overreaches in some areas) When it has some applications where there is no connection between effect and objective of law Case law says this straddle both arbitrariness and gross disproportionality Both arbitrariness and overbreadth also demand the question of how significant the lack of connection must be - is it enough for effects to be inconsistent with purpose (effects actually undermine purpose) or if effects are unnecessary for objective (facts simply show no connection) o Gross disproportionality: law's effects on s7 rights are so serious that they are totally out of sync with the objective (effects are way too harsh) 21 Ratio/importance of case issue case main o Balances the negative effect on the individual against the purpose of the law, not against the societal benefit that might flow from the law The question under s.7 is whether anyone's life, liberty or security has been denied - a grossly disproportionate, overbroad or arbitrary effect on one person is enough to establish breach of s.7 (don't have to balance how many people it benefits or how effective law is in achieving objective) Application: Compare negative effects of law on s7 rights of prostitutes against the objective of the law (first find the objective, then compare to negative effect on s7 rights the more important the purpose looks, the more justified the negative effects of s7) S.210: Prohibiting Common Bawdy House provision: Grossly disproportionate o Objective: AG said to deter prostitution, but court finds objective was really to combat neighbourhood disruption and safeguard public health/safety (prevent nuisance) o Deprivation: endangers sex workers by preventing them from working indoors o Serious effect on safety is totally out of sync with objective of combating nuisance (not such an important government objective) S. 212(1)(j): Living on the Avails provision: Overbroad o Objective: to target pimps and their exploitative conduct o Deprivation: can’t hire bodyguards and other to protect them o Overbroad because it punishes everyone who lives on avails without distinguishing those who exploit workers (like pimps) and those who could increase their safety (like security guards) Not a problem if pimps exploiting sex workers are convicted under the law - this is what the intent is But now sex workers prevented from hiring bodyguards and others who could keep them safe, which has no relation to purpose of law which is to prevent that exploitative kind of relationship S.213(1)(c): Communicating in Public for Purpose of Prostitution provision: Grossly disproportionate o Objective: to take prostitution out of public view to prevent nuisances o Deprivation: displaces prostitutes into less safe, private areas and prevents them from screening clients for drunkenness or violence; out of police eyes/safety o Grossly disproportionate: negative impact on safety is disproportionate response to the relatively trivial possibility of nuisance caused by street prostitution Provisions not saved under s.1 Ratio: o o Charter challenges for arbitrariness, overbreadth and gross disproportionality are distinct Courts have power to strike down legislation that judges find to be irrational when measured against the legislative objective 22 Ratio/importance of case issue main Notes: III. case Parliament introduced new prostitution laws in 2014 – The Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA) PCEPA uses a model of asymmetrical criminalization: Criminalized purchasing but not selling sexual services The actual transaction itself is illegal Criminalizes receiving a financial benefit from the sale of sexual services but exempts non -exploitative relationships Criminalizes communicating for the purpose of prostitution in public places near a school, playground or daycare Criminalizes advertising sexual services (except one’s own) This legislation raises two questions: 1. Is this legislation good public policy to respond to prostitute as a social phenomenon? That depends on whether we see sex work as: Just another form of work, or Inherently exploitative, degrading and dangerous to women This is fundamentally what is underlying the current legislation 2. Is this legislation constitutional? Its effects may be similar to the previous legislation But its objective is different To eliminate the exploitive and degradation of women that is inherent to prostitution The legislation could be challenges on the grounds that it’s grossly disproportional R. v. Safarzadeh- Markhali [2016] – on overbreadth, gross proportionality and arbitrariness McLachlin CJ: In cases on overbreadth, gross proportionality and arbitrariness, identifying purpose of legislation is key. Purpose of legislation is measured against its negative effects Characterize the purpose of law at appropriate level of generality: Not just a general appeal to the underlying social values (it makes it seems the law is more important than it really is it would just inflate the purpose for no reason) But not so detailed that it repeats provision Courts take legislative objectives at face value: judging whether it is appropriate is not part of the s. 7 analysis Evidence of purpose can be found in: Statements of purpose in the legislation Text, context, scheme of the legislation Extrinsic evidence like legislative history and evolution 23 Ratio/importance of case issue case main R. v. Oakes [1986] – Oakes test to save limits on Charter rights IV. s. 1: The Charter guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society. Charter rights are not absolute and can be limited by govt. The burden of justifying the limit will fall to the govt. on a balance of probabilities. The Oakes Test: The test for ‘reasonable limit’ under s. 1 is known as the Oakes test: i. Pressing and substantial objective: “the objective, which the measures responsible for a limit on a charter right or freedom are designed to serve, must be ‘of sufficient importance to warrant overriding a constitutionally protected right or freedom.’” ii. Proportionality test: the “means chosen” to pursue the objective must be “reasonable and demonstrably justified”, balancing “the interests of society with those of individuals and groups”. This broken down into further three qualifications: a) Rational connection – means chosen must be “rationally connected to the objective” – not arbitrary or irrational b) Minimal impairment – the means chosen should impair the right “as little as possible” to achieve the objective – there must be no alternative means to achieve the objective with less rights limitation. o Minimal impairment usually becomes a deciding factor. Often the argument is that the govt. could’ve done something else where rights would not have been limited c) Proportionality of effects – balance the deleterious effects of the right-limiting provision against its objective [later cases clarify: balance the salutary and deleterious effect of the law] Comparing section 7 and section 1 (Bedford): Can a law that infringes s. 7 be saved under s. 1? Historically this seemed unlikely (it would have to be emergencies like times of war). Bedford says maybe infringes of s.7 can be saved under s.1, because s.7 and s.1 are “analytically distinct”: Section 7 puts the burden on the Charter claimant and: Asks if the law’s negative impact on rights offends the POFJ Takes the law’s purpose “at face value” and does not consider its effectiveness Is qualitative not quantitative – an effect on one person is enough Section 1 puts the burden on the government and: Asks if the law’s negative impacts on rights is justified by an “overarching public goal” Measures the law’s impacts on society as a whole – so how many people it affects may be important 24 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 3. The Criminal Process A. Procedural Overview Chronology of criminal process: i. First thing that happens is person gets charged - there's a charging document that says place where offence happened, time and date, and nature of offence conduct If charged, accused's lawyer is going to have to understand what the offence means, and that includes figuring out how offence is classified o More serious offence is, more procedural rights and more severe punishment possibilities (ex: shoplifting vs. murder) Procedural Classification of Offences ii. Classification of Offence: In Code, there are 3 types of offences 1. Summary conviction 2. Indictable 3. Hybrid or dual offences - not really its own category; Crown has choice whether to proceed by indictment or by summary conviction Have to look at offence in Code to see what type of offence it is Type of offence affects: Which court Judge or jury Preliminary hearing or not Best in terms of procedural rights for accused: preliminary hearing in provincial court and then jury trial in Superior Court 25 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Offences triable only on indictment More serious offences - usually offence or penalty section lays out punishment for offences If not, s.743 gives max 5yrs imprisonment 3 kinds: S.469 - Most serious offences known to law Exclusive jurisdiction of superior court (usually by judge and jury)- incl. murder S.553 - Less serious can be dealt with by provincial court judge Least serious indictable offences Absolute jurisdiction of provincial court, judge alone (no right to jury trial for accused, no prelim hearing) Have to look at list of offences listed under s553 of Code For most indictable offences (all those not listed under s.469 or s.553), accused can choose to be tried by prov court without jury, superior court judge without jury, or judge and jury Summary conviction offences Tried by a provincial court judge without prelim hearing and without jury S.787(1): max penalty is $5000 or 6mth in prison or both (default), unless otherwise stated o Example s175(1)(a) …guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction No alternative punishment stated so the default applies Crown election offences (dual, hybrid) Various considerations before Crown elects how to try ie. Higher penalty for indictable, accused prior criminal record, judge shopping In Code, it doesn't explicitly say hybrid, but instead will spell out both summary and indictable options i.e. See Code s.266, see Code s271 - hybrid offence, but even if Crown proceeds by summary conviction, not following the default penalty (higher penalty than for normal summary offences) Various types of trials: Most common: trial by judge alone in provincial court Next most common: trial by judge alone in superior court Least common: trial by superior court judge and jury Types of trial depends on nature of crime o Practice: s. 449 making counterfeit money Check offence provision - it's an indictable offence Check sections 469 and 553 Code is very specific - it must be that exact offence listed It is not listed under either of these lists, which means it is the middle category of indictable offences and so the accused will get to choose mode of trial Purpose of this is to align procedural rights with the seriousness of the offence iii. Preliminary hearing: always in provincial court with judge, no jury Purpose to determine if there is sufficient evidence to proceed to trial - if there is, (if Crown can show prima facie case - on first blush, there's a case) accused is committed for trial OR accused can be discharged and there is no trial (this is the end of the case) Purpose is to screen the charges to be sure Crown has enough evidence to warrant putting the accused through the trial 26 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Defense normally doesn't present any evidence - just looking to see if Crown has enough evidence Defense uses preliminary hearing as a kind of discovery tool - learning more what the Crown's witnesses will say at trial Doesn't make sense from a strategy POV for defense to show evidence iv. Arraignment: The accused appears in court and the charges are read The accused enters a plea: Guilty Not guilty It doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re claiming innocence; but rather, it requires the crown to prove its case. v. Plea bargaining: Agreement between crown and defense for accused to plead guilty Often the accused pleads guilty to a less serious charge, with a joint recommendation on sentence agreed in advance. Beneficial for both parties because crown can save an expensive process Judges not required to follow the joint recommendation on sentence, but they usually do so. There is bargaining power on both sides. vi. Jury selection: Crown and defense can challenge (and keep off the jury) potential jurors who might be biased Jury is normally of 12 persons The must be unanimous in their decision Jury becomes the trier of fact vii. Trial opening statement by crown and defense Witnesses examined (questioned) by lawyers. Note: the questions asked are not the evidence; the ANSWERS GIVEN BY WITNESSES are used as evidence. Examination-in-chief or direct examination (i.e. questioning) lawyer question their own witnesses Cross-examination lawyer questions the witness the other side has brought Re-examination follow up with your own witness after cross-examination The accused has a right to silence and may or may not choose to testify there is no inference of guilt Closing statements by crown and defense Judge instructs the jury on the law Evidence and proof: Crown has the burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt All allegations must be proved by evidence brought forward in court Evidence can be testimony, documents or real evidence Evidence is also testimony people’s stories about what happened 27 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Typically, the guns, bags of bloody gloves etc. are not enough on their own Primarily an opportunity to tell their stories. Direct evidence evidence that directly establishes something that needs to be proven Circumstantial evidence: supports the conclusion that needs to be established but it might need something more viii. Verdict Jury verdict must be unanimous The accused will be found guilty if the Crown has proved guilt beyond a reasonable doubt If not, the accused will be found not guilty and is acquitted Just because not found guilty doesn’t mean the accused is innocent ix. Sentencing if the accused in convicted, the judge imposes a sentence (usually you can bargain with the defense the sentence however not for serious crimes like murder where you automatically go to jail for life): fine a period of imprisonment suspended sentence conditional sentence (ex: house arrest) absolute discharge (found guilty but simply told they can go which is usually for less serious offence) conditional discharge sentence usually has outer limits/boundaries decided by legislation but the common law is highly dependent on for the ranges with various facts taken into account so it is a mix of both common law and legislation for what the sentencing is going to be. x. Appeal Either side may appeal to the court of Appeal Powers of the Court of Appeal Errors in law are the basis of appeals. In jury cases, the error could be in jury instruction. In judge cases, it is errors on how they apply perhaps and it could be on stuff like excluding certain evidence while making Appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada (highest court in Canada): Appeals by leave (permission) of the court (i.e. of SCC) that which are of national importance. Appeals as of right: Accused has a right to appeal to the SCC when a Court of appeal substitutes a conviction for an acquittal, or Either side can appeal by right if there was a dissent in its favor in a point of law at the Court of Appeal 28 Ratio/importance of case issue case main B. Presumption of innocence I. Woolmington v. D.P.P [1935] – accused presumed innocent until proven guilty; case about guy accidentally shooting his wife to death Facts: o o o Woolmington's wife left him after a fight and went to live with her mother W went to ask his wife if she was coming back, and she was shot W said that the gun went off accidentally - he meant to show her the gun and convince her to come back by threatening to commit suicide o He sawed off the barrels of the shotgun, they had been fighting right before and he ran away after she was shot - circumstantial evidence o In his summation to jury, judge said that any killing of another person is murder unless the accused can show that it was something less (prove that it was an accident, out of necessity or infirmity) - possible error in law in judge's charge to jury When the Crown proves that accused killed the victim, it shifts to the accused to prove that it wasn't murder Issue: Is the onus on the accused to prove that it was an accident (prove his innocence)? Holding: Appeal allowed and conviction quashed (in favour of accused) Reasons: (Viscount Sankey L.C.) If at any period the judge could rule that the prosecution proved its case and the onus shifted to the accused to prove he is not guilty, it is essentially allowing the judge to decide the case rather than the jury The accused is entitled to the benefit of the doubt Burden is on the Crown to prove all elements of the offence - onus of proof is not on the accused Crown must prove both that accused killed the victim and that the killing was intentional Prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt Ratio: Accused is presumed innocent, and the Crown must prove all elements of the offence no matter what the charge, not just for murder! Note: Viscount Sankey L.C: “no matter what the charge or where the trial, the principle that the prosecution must prove the guilt of the prisoner is part of the common law of England and no attempt to whittle it can be entertained.” 29 Ratio/importance of case issue case main C. Reasonable Doubt I. A reasonable doubt of guilt can arise by evidence brought forward by the defense but even from evidence brought forward by the Crown. It’s not uncommon for defense to not present any defense of their own at all but simply to point to holes, weaknesses in the cross-examination brought forward by the Crown. The judge has to explain the law to the jury so jury can apply the law. A key thing that judge has to explain is the standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. In a criminal trial, the prosecution has the burden to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt (as opposed to probably guilty) In jury trial, the judge must explain this standard and burden of proof to the jury R. v. Lifchus [1997] – leading case on explaining proof beyond a reasonable doubt to jury – to be explained in every criminal case Facts: o o Accused charged with fraud Trial judge told jury that reasonable doubt should be understood with the ordinary meanings of those words in their “ordinary, natural every day sense.” o Accused convicted and appealed that judge had erred in instructions on meaning of "proof beyond a reasonable doubt" - accused won at appellate level and SCC dismissed Crown's appeal Issue: How should "reasonable doubt" be explained to the jury? Decision: judge made error of law in describing it this way to jury - there is a special meaning to this phrase in context of legal proceedings Reasons: (Cory J) o "beyond a reasonable doubt" has special meaning in legal context that may not be the same as the ordinary meanings associated with those words o In criminal cases, the accused's freedom is at stake, so need to make sure that jurors fully understand the burden of proof o Should be explained to the jury that: Standard of proof beyond a reasonable doubt is linked to presumption of innocence Burden of proof on Crown all through trial (never shifts to accused) Reasonable doubt not based on sympathy or prejudice, but instead on reason and common sense Connected to presence or absence of evidence Not absolute certainty - not proof beyond any doubt or imaginary doubt But does require more than proof that the accused is probably guilty - if this is all they can conclude, must acquit o List of things that judges should NOT say: These are ordinary words, you already know what it means -> it does have special meaning This is the standard people use in making important life decisions in your own life Proof to a moral certainty o Model charge on p.93 bottom- use some version of this charge in all jury cases in Canada 30 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Doesn't have to be a word for word recantation – not meant to be a magical reincantation – but informational content should be there Why don't we use a standard charge? We think it's good for judge to be open to explain concept in relation to the unique facts of the case in order to be more helpful to the jury Ratio: Judge must explain to the jury what a reasonable doubt means in the legal context, not in the ordinary sense. II. R. v. Starr [2000] – confirming a lot of the points on proof beyond reasonable doubt from Lifchus – explained in every criminal case III. Facts: accused convicted of two counts of first degree murder Majority felt that reasonable doubt instruction misled jury Ratio: o Not enough to define reasonable doubt by referring to examples from daily life o SCC adding one extra factor that should be explained to jury in this charge o Should explain that standard is closer to absolute certainty than proof on balance of probabilities (if these standards were looked at from a quantitative POV from 0 to 100 where 50 is probably guilty and 100 is absolute certainty of guilt, beyond a reasonable doubt would be closer to 100 - not in the 50s/60s/70s) o More than a probability that the accused is guilty R. v. S. (J.H) [2008] – special case of explaining reasonable doubt to jury in credibility contest cases (he said-she said) Facts: complainant said her stepfather was sexually abusing her, which he denied (only these 2 witnesses) o Trial judge charged jury on credibility of witnesses, telling them that trial was not a choice between two competing versions of events o Nova Scotia COA overturned conviction and ordered new trial because trial judge did not properly explain principles of reasonable doubt as they applied to credibility o We don't want jury to think that they just have to pick which story they like better "between the two of them I see the complainant is more credible so I'm going to convict the accused" - but even if you believe the complainant more and think the accused is lying, that still might not be proof beyond a reasonable doubt Issue: How should reasonable doubt in relation to credibility be explained? Decision: This charge is fine - not exactly the same - as charge in WD but includes all the main content. Conviction restored. Ratio: (Binnie J) When credibility is a major issue in jury trial, the judge must explain the relationship between assessing credibility and Crown's burden to prove guilt to standard "Lack of credibility on the part of the accused does not equate to proof of his or her guilt beyond a reasonable doubt" Warning the jury not to just pick one side that they like better Just thinking that accused is lying is not enough for conviction - the question is whether Crown has brought enough evidence to prove 31 Ratio/importance of case issue case main The W.D charge: “First, if you believe the evidence of the accused, obviously you must acquit. Second, if you do not believe the testimony of the accused but you are left in reasonable doubt by it, you must acquit. Third, even if you are not left in doubt by the evidence of the accused, you must ask yourself whether, on the basis of the evidence which you do accept, you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt by that evidence of the guilt of the accused.” Binnie J thought that the trial judge was correct in the charge she gave and the Court of Appeal’s charge brushed uncomfortably close to using the WD charge as a magic incantation error. Prof: thinks the charge the trial judge gave in this case is way better and clearer than the WD charge: “You do not decide whether something happened simply by comparing one version of events with another, or choosing one of them. You have to consider all the evidence and decide whether you have been satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that the events that form the basis of the crime charged, in fact, took place.” Wouldn't use this charge in case where it does not involve a credibility contest Relationship between not guilty/declaration of innocence: When an accused person is acquitted, it is not a declaration of evidence in a factual way - jury hasn't determined that person is innocent However, the presumption of innocence still stands - if not proven guilty, that person should be regarded as and treated as innocent The fact that people are not guilty as opposed to getting a declaration of innocence is part of how our system is designed - reality – we don’t want to create a two-tier system in which you would have completely innocent people and those that fall within gray area (i.e. the acquitted/not found guilty ones). Section 11(d) of the Charter IV. S. 11(d): Any person charged with an offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law in a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal. Sometimes, a statute puts the burden of proof on an issue on the defense instead of the prosecution – this is called “reverse onus” and was found unconstitutional in R. v. Oaks. R. v. Oakes [1986] SCC – “reverse onus” burden of proof put on defense by legislation violates s.11(d). Facts: S.8 of Narcotic Control Act: if the court finds accused in possession of narcotic, he is presumed to be in possession for purpose of trafficking --> reverse onus on accused to show on balance of probabilities that he was not in possession for the purpose of trafficking or else would be convicted of the latter, more serious offence Oakes found in possession of eight 1g vials of hashish oil and $620, which he said was from workers' comp cheque Said that he had bought the drugs for his own use Crown proved only that he possessed drugs; automatically presumed to be for trafficking purposes, according to legislation 32 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Trial judge found that it was beyond reasonable doubt that Oakes was in possession, presumed for purpose of trafficking ON COA held that reverse onus clause is unconstitutional because violates s.11(d) presumption of innocence in Charter. Crown appealed to SCC Issue: Is the reverse onus clause in s8 of the Narcotic Control Act in violation of s11(d) of the Charter? If so, is this provision unconstitutional? Holding: SCC dismissed Crown's appeal (in favor of accused). Reverse onus clause in s8 violates the Charter Reasons (Dickson J) When analyzing Charter, must take purposive approach (Hunter v. Southam) - look at what interests the guarantee was intended to protect "Presumption of innocence protects the fundamental liberty and human dignity of any and every person accused by the State of criminal conduct" p.100 o Serious consequences of guilty verdict - loss of liberty, ostracized, etc. o For this reason, we require state to meet high burden of proof beyond reasonable doubt o "presumption ensures faith in human kind- presume others to be law abiding until proved otherwise" Presumption included in many international human rights documents as well - widespread acceptance S11(d) at least means: o Individual must be proven guilty beyond reasonable doubt o State has burden of proof - where there is reverse onus, accused has to prove innocence rather than state proving guilt o Prosecution must be carried out in accordance with fair and lawful procedures "If an accused bears the burden of disproving on a balance of probabilities an essential element of an offence, it would be possible for a conviction to occur despite the existence of a reasonable doubt" p.102 The fact that the onus on the accused is at lower standard does not make it constitutional Ratio: A “reverse onus” of burden of proof place on the accused, whether this relates to an element of the offence or defence, violates s.11(d) and the only question is whether it can be saved under s1 (sometimes it can be upheld under s1 for some overriding social policy reason) D. Victims’ Rights Since a criminal trial is between the state and the accused, a victim does not necessarily have a formal part in the process Often the victim is simply a witness That can lead to particular problems that causes difficulties for victims in this trial process Victims have often had very negative experiences in the criminal justice system: Victim is not told about plea bargain in a timely manner They have very little influence on the process Esp. in sexual abuse cases, there is humiliating treatment that victims are subjected to in criminal trials, due to cross examinations. “whack the complainant” defense lawyers hope to scare off the victims in the preliminary inquiries, so they don’t come back during the actual trial. (obviously very unethical). 33 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Attempts remedy this problem have included: The adoption of rape shield laws and, More recently, the Victims’ Bill of Rights Mechanisms to keep the victims informed about the trial Protection from intimidation One mechanism through which victims can have their voice heard is through Victim Impact Statement: Not necessarily good to let the victim dictate the entire sentencing because it could be based on the victim’s own personal values, which would contradict the legal system It is also unfair because it could be different from victim to victim They could be useful in telling the court how the crime has impacted them and the court can take that into account, even if it doesn’t exactly tied in to the actual sentencing. When is the state justified in making conduct into a crime? Philosophical justification of making conduct a crime Controlling anti-social behavior through criminal law should be last step Need to have restraint in scope of criminal law - should be as narrow as possible E. Scope of the Criminal Law Practical Scope: In reality, common charges include: Theft Impaired driving Common assault And breach offences (justice system offences): failure to comply with a court order Breach of probation It is problematic the criminal justice systems requires a lot of compliance with its own internal procedures like meetings with probation officers as opposed to the general behaviors of their offence ex: not stealing anymore. As a result, you become caught up in the criminal justice system because you become guilty of not complying with those internal procedures. Further, people who have low social support usually end up getting more caught up in the criminal justice system because it is harder for them to comply with the internal procedures like probations as opposed to those who have more social support. Indigenous people are vastly overrepresented: As victims of crime And as accused persons/inmates 34 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Normative Scope: I. When is the state justified in imposing criminal punishment? Some suggest the scope of the criminal law is limited by the “harm principle” The harm principle is the idea that the state is only justified in punishing individuals for conduct that harms others The harm principle is discussed in R. v. Malmo-Levine Criminal law costly not just in monetary terms of putting people into jails the expense of the process itself, but also for the suffering it causes to families etc. R. v. Malmo-Levine [2003] – harm principle not a PFJ – how to classify PFJ Facts: Mill’s Harm principle – prohibition of acts that cause harm to others (ex: theft) Appellants argued that the harm principle is a principle of fundamental justice that violates s.7 and thus Canada’s marijuana laws are unconstitutional (because no harm to others). Clearly individual liberty restriction is in play with the possibility of punishment of possessing marijuana, which causes no harm to others. Issue: is the harm principle a principle of fundamental justice under s7 of the Charter which places limits on the type of actions that the state can properly criminalize? Decision: Upholding the constitutionality of Canada’s marijuana laws, the SC firmly rejected the notion that Mill’s harm principle is a principle of fundamental justice that would violate s.7 Reasons: Binnie JJ: Harm principle does 2 things: i. Reject paternalism (prohibiting actions that harm only the actor himself) ii. Rejects notion of moral harm – moral claims are insufficient to justify criminalizing certain acts; Mill requires clear and tangible harm to the rights and interests of others for criminalizing certain acts. Harm aspect just one of the many factors in determining whether an activity is to be criminalized or not Justification for state intervention cannot be reduced to a single factor – harm – but is a much more complex matter Harm principle does not meet the requirements of being a PFJ on three grounds: Harm principle normative principle for state action, not a legal principle. Not attract “significant societal consensus that the harm principle is fundamental to the way in which the legal system ought fairly to operate” Ex: cannibalism is a crime under the code even though no harm to sentient being harm not the only way we criminalize conduct. Weak argument to rely on other codes not fitting the harm principle to show that harm is not a PFJ maybe those codes are unconstitutional too!! Doesn’t yield with sufficient precision a manageable standard against which to measure deprivations of life, liberty or security of the person.” 35 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Stronger argument because… Not a manageable standard because what counts as harm is highly debated and contested and so hard to pin down what counts as harm Arguments of non-trivial harm can be issued on both sides (ex: one side argues about the harm of criminalizing it causing disruptions of family etc. vs the other side who are trying to uphold the law argue that the use and abuse of marihuana is harmful to oneself and to other persons who may come into contact with the user – alteration of mind and thus could lead to dangerous driving etc.) Ratio: state may create laws criminalizing behavior that is not harmful (according to the harm principle) or that which causes harm only to the actor. Can include acts which offend societal notions of justice/ social values Canada still has paternalistic laws to save people from themselves i.e. Seatbelts whether a jail sentence is an appropriate punishment or not for these offences is the debate, but this doesn't relate to the validity of the prohibition of that behavior itself Harm to oneself often has an impact on others! F. Adversary System Civil and criminal trials in Canadian courts are adversary proceedings Three prominent features of adversarial system: Pros: Point of pride in our system that the judge is impartial Better at truth seeking – two sides working hard to illuminate the facts instead of just one judge investigating (a common feature of systems in Europe) Both parties bring evidence to court by acting in their self-interest Both parties gain even if the result not in favor because they can have “their day in court” and get something out of the process (a sense of satisfaction) Cross examination helps with truth seeking 36 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Cons: The vision of the procedure is as a contest adversaries might be formally equal but substantively unequal in terms of wealth (ex: an accused person may not have enough money to hire a lawyer, hire experts etc.) A very binary type of system with the outcomes being win or lose Implications for civil cases in which families are further broken apart by win/lose binary the system reinforces that rather than bringing the families together real truth hidden – prevent evidence that might be unfavorable to their position so lawyers may present best picture of client’s position, not the complete picture impediment to search for truth for facts that are in the past – really relying on testimonies of witnesses from what they now remember as facts so really just guesses about the actual facts Steve Coughlan, “The ‘Adversary System’: Rhetoric or Reality” [1993] SCC has said that the role of the prosecutor does not include considerations of winning or losing…focus on presenting all legal proof of facts as a matter of public duty Idealized role of the prosecutor in Canada is they have a public duty and so “excludes any notion of winning or losing” SCC Saying that the prosecutor's role is not that of an adversary - but then how do we have an adversarial system? Many prosecutors do see themselves as an adversary – i.e. through cross-examining witnesses, poking holes in the defense so not completely non-adversarial Examples of negotiation and win-win model: plea bargains, alternative sentence recommendation for young offenders Prosecutors can't be forced to agree - must work together Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Portia in a Different Voice: Speculation on a Women’s Lawyering Process [1985] Logic of justice (balance of rights) vs. ethic of care (responsibility to relations) to approach Heinz’ dilemma: Because of how men and women are socialized, there are trends in how men and women approach moral problems Heinz problem: H's wife needs a lifesaving drug, pharmacist is asking for too much money, so should H steal it? Boys tend to look at competing rights of life and payment, so we should steal it Girls want to get everyone to be satisfied, keep relationships intact Both ways of looking at the problem are legitimate, but historically authors have seen the male way of looking at it as more morally developed Moving away from adversarial system towards more win-win, ethic of care approaches is valuable Adversary system impedes not only the supposed search for truth, but also hinders expression of concern for the person on the other side Alternative dispute resolution: modifying the harshness of the adversarial model 37 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Ethic of care approach tries to produce the best outcome for all parties concerned, as opposed to just win/lose binaries. Ethic of care also focuses more on mediation method that in some cases better caters to client needs The values that Meadow advocates for such as ethic of care are just ideas that have been associated as feminine values and thus have been excluded from the legal profession’s framing. Madam Justice Bertha Wilson, Will Women Judges Really Make a Difference? [1990] Judges are supposed to be completely impartial - many have questioned whether this it is possible for judges to separate themselves from their personal opinions But some question what the value of diversity is if judges are supposed to be impartial? I.e. A woman judge can't go the bench and make a point of convicting all sex assault accused to advocate for women Yes, there will be a difference Historically, judges have all been men -assumed to be impartial But what if judges do bring their own values and experiences with them? In that case, more female judges may have an effect! Women judges shatter stereotypes and ensure public is confident in those who are making decisions that will affect them Carol Gilligan: women have different responses to moral dilemmas than men (how they think about themselves in relationship to others) Men see moral problems through lens of competing rights: adversarial system comes naturally Women see moral problems as arising from competing obligations, and goal is to achieve optimum outcome - ethic of caring (echoing the Meadow article above) Current adversarial system wants to remove context and focus on bare bones of the facts Aboriginal Peoples and Criminal Justice – Law Reform Commission of Canada [1991] Summarizing report by the Law Reform Commission of Canada on: Aboriginal Peoples and Criminal Justice Report starts off by acknowledging that its findings are an oversimplification of the aboriginal perception on the justice system, due to a number of communities in the system and thus different experiences Still, there is a uniformity that can be drawn Report first summarizes the aboriginal perceptions: Criminal justice system racist towards Aboriginal (imposed by the white society) It is insensitive to Aboriginal values and beliefs Police are not a source of stability but rather instill a sense of fear in the indigenous through abuse of power and discretionary judgement Many indigenous live in remote reserve communities – so not only is the whole system alien to them because of physical access Further isolation caused by the process itself where language is a barrier, and system where judges, police officers, lawyers etc. don’t explain the process adequately to the aboriginal victims or accused persons (further tying in to racist ideologies) 38 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Little confidence from the system – esp. in how it treats their youth who return from the system to their communities and the elders find their rehabilitation difficult Aboriginal aspirations: Aboriginal people have for long strived towards the goal of self-govt. with their own values and beliefs governing them Similar goal for the criminal justice system as well Hence, a system that would give due respect to the community elders, take into account aboriginal spirituality and the relationship between humankind to the land etc. Essentially their vision of justice is more community based rather than individualistic – a system that seeks to reconcile the offender and victim but also to reintegrate the offender back into the community Statue laws insignificant – due to laws varying from one aboriginal community to another, customary practices of the particular community would govern the system The excerpt ends on a note of uncertainty as to what this system would look like, not because aboriginal communities don’t have working models (which in fact they do), but rather because they don’t feel oblige to provide it because they don’t want any more interference in their aspiring goal towards self-governance Rupert Ross, Dancing with a Ghost Rupert Ross was an assistant Crown Attorney who worked closely with the Ojibway and Cree peoples to make the court system more responsive to the needs of their communities He noticed the difference in aboriginal approach to crimes and legal systems Ex: a rape victim refusing to testify because “it’s not right to do this after so much time. He should be finished with it now and getting on with his life.” Victims often question if their testimonies and saying certain things in their defense is the “right thing to do”. Important to recognize that the indigenous people have a highly developed, formal but radically different set of cultural imperatives, especially when it comes to legal systems. We end up misinterpreting their acts; misperceiving the real problems they face By imposing them to govt. policies, we subject them to potentially harmful “remedies” Our court system is obsessed with maintaining the peace Native approach concentrates instead on the personal or interpersonal dysfunctions that caused the problem in the first place Correcting those dysfunctions Integrating and rehabilitating the offenders back into society, unlike the court system that just locks them away. Honoring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future [2015] Important to educate lawyers with residential school survivors with sensitivity By developing a greater understanding of Aboriginal history and culture Multi-faceted legacy of residential schools Call to Action by the Commission: 39 Ratio/importance of case issue case main “Call upon Federation of Law Societies of Candaa to ensure that lawyers receive appropriate cultural competency training…including history and legacy of residential schools, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” “Call upon law schools in Canada to require all law students to take a course in Aboriginal people and the law…including history and legacy of residential schools, UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples…” I. R. v. R.D.S [1997] – Reasonable Apprehension of bias test – whether judges should bring context/personal values to judgements Facts: A young 15-year old black boy arrested by a white police officer because he interfered with the arrest of another youth Only two witnesses in the trial Officer claims RDS rammed his bike into him RDS claims he only rode up and asked what happened when officer told him to shut up The judge acquitted the accused and the crown hadn’t proven beyond reasonable doubt that the accused had rammed his bike J. Sparks: first black judge in Nova Scotia. Acquitted the accused while making the comment “…police officers do overreact, particularly when they are dealing with non-white groups. That to me indicates a state of mind right there that is questionable. I believe that probably the situation in this particular case is the case of a young police officer who overreacted.” Defendant claimed judge was biased or showed a reasonable apprehension of bias towards RDS Issue: Would a reasonable, informed person, aware of all the circumstances, conclude that her comments gave rise to a reasonable apprehension of bias? Not the same test as proving beyond a reasonable doubt Maxim is that justice should not only be done but seen to be done as well Decision: By applying the test of the reasonable apprehension of doubt, the trial judge was found to not have been bias in her decision and thus acquittal upheld. Reasons: Split of 6-3 in favor of acquittal: J. Cory (concurring with another judge): Remarks were worrisome and close to the line in the sense that it could be stereotyping all police officers even when there isn’t proof We have to rely on specific evidence, case specific and not on general facts (ex: police officers overreacting in general towards non-whites) Nevertheless, even though it is close to the line, it did not raise RAOB (reasonable apprehension of doubt) because of the CONTEXT in which Judge Sparks made the comments: 40 Ratio/importance of case issue case main The comments made by Judge Spark were just responsive to the Crown’s arguments that the police officer should be believed because he’s a police officer judge Sparks was only responding to this that there could be a plausible reason for doubting the credibility of the police officer (based on the past treatment) Judge Major + 2 dissent: Similar reasoning to J. Cory but different conclusion There is no case specific evidence that the police officer acted on racial bias which would clearly raise RAOB Judge Sparks was clearly using just her life experiences and overall stereotyping of how white police officers treat black people when she made those comments (as opposed to being responsive as J. Cory J. L’Heureeux-Dube (along with one more judge in favor of acquittal): There is circumstantial evidence that there was a racially motivated overreaction if you look at the overall circumstance Police officer had two youths arrested and pinned, so that’s circumstantial evidence of how the police officer overreacted Judge Sparks actually did not find that the police officer had overreacted but rather that the crown hadn’t proven beyond reasonable doubt that the youth had reacted. The judge was taking into account the racial tensions as any well-informed person would they called it contextualized judging J Gonthier + 1: On board with the previous two on contextual judging No RAOB Ratio: Generalizations in enough of themselves is not enough grounds to make decisions; there needs to be case-specific evidence. The judgement that’s most authoritative, however, is Judge Cory’s and lead judgement: He’s majority in the sense that he found that the remarks were worrisome (3 other judges found that) He’s also in majority of the decision itself He’s also in agreement with 4 other on the reasoning/legal principle applied in analyzing the case, even though he came to a different result than 3 of the other judges (i.e. J. Major and the other two) Despite that, this case is 20 years old and today, L’Heureux-Dube’s judgment would be the majority because yes, judges are allowed to know/should bring into consideration racial tensions in the community. There is higher recognition of racial bias within the system and thus higher contextual judgements. 41 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Personal thoughts on this case: context of J. Spark’s decision resulted in a lot of backlash. What if a white judge had acquitted the teenager? L’Heureux-Dube’s decision at that time was very bold but not anymore. BEF Excerpt Black community don’t view the criminal justice as being impartial (even though that’s what the adversarial system claims to be) It’s a large project done in terms of survey research, one being with their experience with the criminal justice system One concern was racial profiling and targeting of them by over-policing them Black Experience Project in the GTA, 2017 Experience with Police Services and the Criminal Justice System - Police and criminal justice system provide ○ Security for people and property ○ Justice by holding people accountable and supporting the innocent ○ Equity by acting impartially and without prejudice, so unlike other places, Canadians aren't subject to arbitrary/excessive exercise of state power - Black people and other racialized groups/Indigenous people have not been able to enjoy these as fully - compromised by troubled relationship - Overrepresentation in prisons - Excessive police surveillance, police presence in largely Black neighborhoods, police brutality, carding, stops, search and seizures, numerous police killings of young unarmed Black men, extra judicial and illegal drug raids - Racial profiling, systemic police bias, anti-Black racism - Researched in two areas - direct experiences of BEP participants with police/criminal justice systems, and attitudes towards their performance in terms of protecting citizens and treating Black people fairly - Experiences with police ○ Majority had negative experiences - more likely to happen to them ○ Irrespective of education, income, employment levels ○ Men between ages of 25 and 44 especially ○ Women more likely to have needed help ○ Many people have a mixture of experiences, good and bad ○ Good-to-average job - but more than half say they do a poor job of treating black people fairly ○ Consensus that unfair treatment because they are Black - Experiences with criminal justice system ○ More than half had personal involvement in last 10 years - either visiting someone, attending public information sessions, as a witness, or victim ○ 1 in 10 as someone who did wrong - higher among 25 to 44 men ○ 39% felt treated unfairly, most often because Black - Partner with the community, show respect/don't be dehumanizing, require ongoing training G. Sentencing Principles purpose of punishment In philosophy, two main schools of thought: Retributivism – punishment imposed in response to and in proportion to morally blameworthy acts – “just deserts” i.e. getting what they deserve Consequentialism (utilitarianism) – punishment imposed in pursuit of good outcomes, social goals, e.g. to deter future crime Our system does not embrace either theory in its pure form (which philosophers don’t like that because they find the two theories inconsistence with each other) Sentencing has some consequentialist objectives: e.g. deterrence, incapacitation Punishment also has retributive elements: e.g. a sentence that is too harsh is not just and appropriate on retributive principles Denunciation is also a legitimate sentencing objective - communicating society’s condemnation of the conduct 42 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Purpose of sentencing: s. 718: “the fundamental purpose of sentencing si to protect society and to contribute, along with crime prevention initiatives, to respect for the law and the maintenance of a just, peaceful and safe society by imposing just sanctions that have one or more of the following objectives: a) b) c) d) e) f) To denounce…. To deter… To separate offenders from society… …rehabilitating offenders …reparations for harm done… …promote sense of responsibility. Fundamental principle that governs sentencing: s.718.1: a sentence must be proportional to the gravity of the offence and the degree of responsibility of the offender. H. Aboriginal Sentencing I. Criminal code speaks specifically to the sentencing in Indigenous offenders: S. 718.2 A court that imposes a sentence shall also take into consideration the following principles: … e). all available sanctions, other than imprisonment, that are reasonable in the circumstances and consistent with the harm done to victims or to the community should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of Aboriginal offenders. R v. Gladue [1999] – interpretation of s. 718.2(e) for Aboriginal S. 718.2(e) is meant to be remedial and calls for a different method of analysis Recognizes the sentencing of the indigenous Judges need to consider unique, systemic, background factors might have played a role in this person getting involved into the criminal justice system Requires consideration of case-specific information Gladue Reports (subsequent to R. v. Gladue): Bring information about the accused and their background factors, including residential schools etc. They also give information on specific aboriginal values of sentencing that might be appropriate. TRC Report acknowledged that Gladue reports are not equally available to aboriginals all across the country – some indigenous get access to them while others don’t. 43 Ratio/importance of case issue II. case main R v. Ipeelee [2012] – Aboriginal sentencing SCC rejects three key critiques of Gladue: 1. Sentencing is not an appropriate or effective means of addressing overrepresentation SCC rejects this view that sentencing has no role – rather, it is one step that needs to be taken in conjunction with many to strive against overrepresentation 2. Gladue creates an unprincipled race-based discount on sentence Courts making sentences that is proportion to the gravity of the offence Degree of responsibility of the offender comes from his background so it’s really moving away from the criminal code sentencing but rather upholding it 3. Unfair to distinguish offenders from others who are similarly disadvantaged indigenous have special status under law because of their history with the crown as opposed to other disadvantaged groups even then, Gladue does not say we can’t taken into account similar factors for other groups Errors made by courts in applying Gladue: Holding that the offender must establish a “causal link” between the background factors and the offence Holding that Gladue does not apply to serious offences. I. Ethics of Crown and Defense Obligation of defense lawyers include: Duty of confidentiality Duty of loyalty to the client Duty to advocate for the client, within limits of law Duty to treat the court with fairness, courtesy and respect Prohibition on assisting clients to act dishonestly or dishonorably Prohibition on deceiving a tribunal – e.g. by providing false evidence, misstating facts or law Obligation of prosecutors include: Duty to seek truth and justice, to act as a “minister of justice” – no winning/losing role Duty to act and exercise discretion fairly and impartially – for please bargains etc. Duty to disclose all relevant evidence to the defense 44 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 4. The Act Requirement 1) Introduction Elements of an offence: those things that Crown must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt to convict All criminal offences have at least: An ACT element, and A Fault element Expressed in a Latin maxim: actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea= there is no guilty act without a guilty mind Depending on offence, it may or may not have a consequential and circumstantial event. External elements - externally manifested Fault elements - deal with level of moral blameworthiness of the accused person Act element (actus reus, guilty act) - action by accused Mental element (mens rea, guilty mind) - have to show that the accused knew something or intended a particular consequence to come about Circumstance elements - elements of the offence that have OR to be proven by Crown that are in circumstances, not something that the accused does (i.e. S177: trespassing at night - circumstance element is that it must be at night), or assault element requires absence of consent Consequence elements - some crimes require a certain consequence to happen (i.e. Offence of murder requires the victim to die - if you intend to murder someone and shoot them but they don't die, you are morally blameworthy but can't actually be convicted of murder) Negligence - whether the accused should have known something or what the consequences could be 45 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 2) Consent making act lawful Sometimes an act is only an offence if it is done without consent In order to prove the act, you would have to prove there is no consent See for example the definition of the offence of assault: 265 1): a person commits an assault when a). without the consent of another person, he applies force intentionally to that other person, directly or indirectly… Absence of consent is an element of the offence of assault (consent would be a circumstantial element…broadly speaking it is part of the act element but narrowly in the fault element it is circumstantial) Defense for an assault could be that THERE WAS consent Vitiating Consent: For consent to make an act lawful, the consent has to be valid In some situations where consent was apparently given, consent is vitiated “vitiated” means invalid in the eyes of the law for some reason, even if there was consent between the two parties. Ex: even if a child seemingly consents to sexual activity, it is vitiated under law due to the age limit for consent to sexual activity being 16 years of age. Consent vitiated in the eye of law or if induced by fraud. I. CODE: R v. Jobidon [1991] – FIST FIGHT!! consent vitiated by common law limits – assault without consent – no consent to death – culpable homicide Facts: s.265(1)(a): a person commits an assault when without the consent of another person, he applies force intentionally to that other person, directly or indirectly. s.14: no person is entitled to have death inflicted on them, and such consent does affect the criminal responsibility of any person who inflicts death on the person who gave consent. s.222(5)(a): A person commits culpable homicide when he causes the death of a human being by means of an unlawful act. Victim and Jobidon consent to fist fight at a bar and agree to take it outside to parking lot Jobidon knocks victim onto hood of car and victim falls unconscious while J continues a few more punches, not realizing he is unconscious. Victim dies from concussions to the head Trial judge: Both had intention to inflict pain but not kill There was consent Jobidon did not know he was unconscious 46 Ratio/importance of case issue Issue: Decisions: Reasons: Ratio: Notes: case main Question then is whether the punching was an assault or not – it was an assault, then guilty of manslaughter. If not an assault, then not guilty. Trial judge acquitted him. Court of Appeal convicted Jobidon for manslaughter Jobidon then appealed to the SCC Was the fistfight consensual? Was the consent to a fist fight valid or did something vitiate it in the eyes of law? Appeal dismissed.; Jobidon convicted of manslaughter because consent is vitiated. Gonthier J (majority 5): Limits to consent in the code such as s.14 and limits in common law AS WELL Accused went beyond common law limits and convicted based on those (since no such limits in the statutes) Acknowledges common law influences, so long as there are no inconsistencies with the criminal code. Further, the majority points to s.8(3) of the code and if its interaction with the common law principles can be used to authorize new defenses not found in the Code, then courts can surely explain the boundaries of these defense. Policy based limits: Fist fight can lead to larger breaches of peace, needs to be deterred/discouraged and because it is socially useless and has no value (unlike other risky activities like sports and circus). Sopinka J (Concurring): Court has no right to make public policy limits on consent when code says consent makes it not an assault “consent cannot be read out of the offence”. Agrees with conviction but disagrees with trial judge’s finding that Jobidon did not know victim was unconscious – Sopinka argues he knew he was unconscious and at that point, consent no longer applied. “The limitation demanded by s.265 as it applies to the circumstances of this appeal is one which vitiates consent between adults intentionally to apply force causing serious hurt or non-trivial bodily harm to each other in the course of a fist fight or a brawl.” For Jobidon limit to apply, serious hurt or non-trivial bodily harm must be BOTH INTENDED and CAUSED. The ratio could apply narrowly to other examples of fist fights/brawls but also to similar cases around vitiating consent where bodily harm occurs – ex: sexual activities that are consented to Bodily harm: Jobidon vitiates consent where SERIOUS OR NON-TRIVIAL BODILY HARM IS BOTH INTENDED AND CAUSED Bodily harm for this purpose is defined in s.2 as “any hurt or injury to a person that interferes with the health or comfort of the person and is more than merely transient or trifling in nature.” Bodily harm<serious bodily harm<harm required for aggravate assault (s.268: wounding, maiming, disfiguring or endangering the life of the victim.” 47 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Consent vitiated by fraud: s.265(3)(c): [in assault cases], no consent is obtained where the complainant submits or does not resist by reason of fraud. If people apparently consent to touching but they do that on the basis of some fraudulent representation by the other person, consent may become invalid. Historically, consent to sexual activity vitiated very narrowly – either based on the identity of the partner, or not knowing that the nature and quality of the act was a sexual activity. II. R. v. Cuerrier ([998] – HIV case – consent to sexual activity vitiated – aggravated assault – Cuerrier test of “bodily harm” Code: Facts: Issue: Decision: Reasons: s.265(3)(c): [in assault cases], no consent is obtained where the complainant submits or does not resist by reason of fraud. (applies to all forms of assault and sexual assault) s.268(1): Every one commits an aggravated assault who wounds, maims, disfigures or endangers the life of the complainant. Cuerrier charged with two counts of aggravated assault pursuant to s.268 of Criminal Code He tested positive for HIV and was told to use protection and tell partners – he refused Had unprotected sex with two complainants without disclosing status Complainants said they consented to unprotected sex, but would not have done so if they had known of his status Procedural History: Trial: accused acquitted Appeal: acquittal upheld What is the meaning of fraud under s. 265(3)(c)? Does non-disclosure of HIV status amount to fraud vitiating complainant’s apparent consent to sexual intercourse? Appeal allowed. New trial ordered. Consent was vitiated by fraud by non-disclosure (unanimous in holding but split in reasons) Test of bodily harm: “significant risk of bodily harm” – more than any risk but less than high risk J. Cory (majority 4/7): no longer necessary to see if fraud goes to just identity and the nature and quality of the act; we’ve move beyond those narrow lines Look at common law to look at what fraud means 2 elements of fraud: Dishonesty: lying to someone or just not telling the truth (when there is an obligation to disclose information) AND Deprivation: includes putting others at risk (either others have been harmed or put at risk) Crown has to prove that the complainant wouldn’t have otherwise consented if there had been declaration of the guy being HIV positive You have to have both dishonesty and depravation If defense can show that sure they were dishonest, but if there wasn’t any depravation, then there is no fraud. 48 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Fraud vitiates consent when it is dishonesty that exposes the person consenting to a “significant risk of serious bodily harm” (pg. 232) The greater the risk, the greater the obligation to disclose HIV could have fatal consequences Failure to disclose HIV you had a huge duty to disclose Justice L’Heureux-Dube (concurring…1/7): Fraud vitiate consent where “the deceit deprived the complainant of the ability to exercise his or her will in relation to his or her physical integrity with respect to the activity in question.” (pg. 233) Defines deceit/fraud very broadly so could perhaps extend what types of sexual assaults will be ex Justice McLachlin (concurring…most conservative 2/7): Fraud traditionally vitiated consent in cases of “deception as to the presence of a sexually transmitted disease giving rise to serious risk or probability of infecting complainant.” Make only incremental changes very narrow judgement as to only fraud in sexual assault cases Ratio: Fraud can vitiate consent when it is dishonesty that exposes the person consenting to deprivation in the sense of a “significant risk of serious bodily harm.” L'Heaureux-Dube's decision is most consistent with changes in criminal law surrounding sexual assault Notes: III. R. v. Mabior [2012] – no assault because HIV guy used protection and had treatment -aggravated sexual assault in Code Code: Facts: Issue: Decision: Reasons: s.273: Every one commits an aggravated sexual assault who, in committing a sexual assault, wounds, maims, disfigures, or endangers the life of he complainant. Accused charged with aggravated sexual assault under s 273 9 complainants had sex with Mabior, not knowing he was HIV positive He had received treatment that reduced his viral load to low level (had fewer copies of the HIV virus in his blood, which makes him a lot less infectious to partners) They said they would not have had sex with him if they knew he was HIV positive, but none of them contracted HIV He sometimes used a condom Does the Cuerrier test apply? If it does apply, how does it apply to the question of low viral load and condom use, not dealt with in Cuerrier? On the count where there is low viral load AND protection used, consent is not vitiated and Mabior acquitted. McLachlin J (majority): Need to build certainty into the Cuerrier test by indicating when the significant risk test is met 49 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Test requires disclosure of HIV status if ther eis a realistic possibility of transmission of HIV. In the context of non-disclosure of HIV+ status, consent will be vitiated by a “Realistic possibility of transmission of HIV” but if no realistic possibility of transmission, then failing to disclose will not be fraud vitiating consent under s.265(3)(c). There is no realistic possibility of transmission where: Viral load is low, AND A condom is used Ratio: Notes: IV. Code: Facts: Issue: "To obtain a conviction under ss. 265(3) (c ) and 273, the Crown must show that the complainant's consent to sexual intercourse was vitiated by the accused's fraud as to his HIV status. Failure to disclose (the dishonest act) amounts to fraud where the complainant would not have consented had he or she known the accused was HIV positive and where sexual contact poses a significant risk of or causes actual serious bodily harm (deprivation). A significant risk of serious bodily harm is established by a realistic possibility of transmission of HIV…A realistic possibility of transmission is negated by evidence that the accused's viral load was low at the time of intercourse [AND] that condom protection was used" p.237 Still gonna use Cuerrier test of significant bodily harm How this applies in HIV is realistic possibility of transmission No realistic transmission possibility if condom AND low viral load Criticisms: Those who see HIV positive individuals as marginalized don't see why HIV positive people should have to disclosed if they get therapy which reduces the risk of transmission and why condoms also need to be used to avoid criminality Those who advocate for complainants say that even if risk is low, should be disclosed for informed decision making R. v. Hutchinson [2014] – consent in code – woman agrees to sex ONLY WITH CONDOM – guy pokes holes in condom – girl pregnant s.273.1(1): Subject to subsection (2) and subsection 265(3), “consent” means, for the purposes of sections 271, 272 and 273, the voluntary agreement of the complainant to engage in the sexual activity in question Hutchinson poked holes in condom and partner became pregnant Charged with aggravated sexual assault All judges agreed that he was guilty and that there was no effective consent, but didn't know how to classify the non-consent Did the complainant never consent to the sexual activity in question, namely sex without a condom; or was the complainant's consent vitiated by fraud during the act? (agreement that consent was not effective, but disagreement amongst judges as to why it wasn't effective) 50 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Decision: There was consent, but that consent was vitiated by fraud Reasons: McLachlin CJC (majority): Because technically she did consent to the act of sexual intercourse, but it became vitiated during the act when the accused misrepresented Going back to Cuerrier for the test significant risk of serious bodily harm test: It really applies to sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV, herpes and other STIs. Here, we’re looking at another type of harm where a woman becomes pregnant without consent and suffers the risks of abortion Cuerrier doesn’t apply directly but by analogy because getting pregnant and the abortion risks involved are analogously serious to resulting in harm to the complainant as an STD would be. Thus, Cuerrier is more directly applicable to STDs but can apply to other cases indirectly through analogy if you have serious bodily harms involved. Ratio: If a complainant has chosen not to become pregnant, deceptions that take away her choice by making her pregnant or increasing her risk of become pregnant by removing effective birth control, may constitute sufficiently serious deprivation for purposes of fraud vitiating consent 51 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 3) Omissions I. An omission to do something is a criminal act General rule: failure to act does not give rise to criminal liability BUT AN EXCEPTION: an omission can ground criminal liability where there is a legal duty to act Legal duties are narrower than moral duties There are situations where we think people should intervene or act but where that person does not have a legal duty to act so no criminal liability. Buch v. Amory Mortgage Co. [1898] – law’s individualistic approach to defining when there is a legal duty to act Acting like the good Samaritan is the right thing to do The common law doesn’t require this, however. There is no general duty to rescue in the common law, unlike the Quebec Charter of Rights which does require this duty along with some European codes such as the French Penal Code Justification of no duty in the common law: Where would you draw a line? How far do you go rescuing the other person at your own cost? The law is good at drawing the line so not really a good argument… Once you get involved in a rescue, you could be causing more problems It really reflects the common law’s individualistic philosophy each person should be entirely free to do what they want for themselves unless they’re doing something that might interfere with other people’s rights That doesn’t mean you have no legal duties there are cases when you do… Legal Duties found in the Code Some legal duties to act are found in statute The Criminal Code imposes several important duties to act, for example: Section 215 duties to provide the “necessaries of life” to one’s children, one’s spouse, and people under one’s charge. Ex: duty to give food, medical care and shelter to my kids Section 216 duties of those undertaking medical or surgical treatments or doing other lawful acts that may endanger life Ex: you can’t be performing brain surgery if you’re not a neurosurgeon or a drunk one Section 217 duty to follow through on undertakings where an omission to act would be dangerous to life Section 217.1 duty of those directing others’ work to take reasonable steps to ensure safety Construction sites where responsibility of contractors to ensure proper safety equipment and environment for their workers 52 Ratio/importance of case issue case main In addition, duties to act may be found in the common law. If legal duty in common law or provincial statutes that could ground criminal liability on that, that’s just turning a common law/provincial statute into an offence which is problematic because it would be different from one province to another based on each province’s provincial statutes. Liability for Omissions – Requirements: s. 215 or 217 that creates duty is not in itself an offence – they are duties to the effect which can make the omission an offence. No one is charged for failing to undertaking under s. 215 – rather they are charged with an offence An omission can ground criminal liability where: 1. The offence is one that is capable of being done by omission 2. The accused was under a legal duty to act under one of: The Criminal Code Another statute, federal or provincial The common law II. R v. Browne [1997] – girl swallowed cocaine and her partner calls taxi instead of ambulance to take her to hospital – no undertaking [defined here] of a legal duty so not guilty Code: Facts: Issues: Decision: Reasons: s.217: Everyone who undertakes to do an act is under a legal duty to do it if an omission to do the act is or may be dangerous to life. s.219(1)(b): everyone is criminally negligent who in omitting to do anything that is his duty to do, shows wanton or reckless disregard for the lives or safety of other persons. 219(2): for the purposes of this section, “duty” means a duty imposed by law. Deceased and accused drug dealing partners Deceased swallowed bag of cocaine – few hours later, showed symptoms of overdose Accused said he would take her to the hospital – called taxi which took time to arrive and another 15 min to get to the hospital. Deceased dead at arrival to the hospital Browne charged with criminal negligence causing death under s.219 Did Browne undertake to do an act giving rise to legal duty? Browne not guilty of criminal negligence because there was no undertaking For the court of Appeal, J Abella of ON COA defines an undertaking under s. 217: Not about the relationship between the two but rather whether there is an agreement between the two that there will be an undertaking A “binding commitment” “clearly made, and with binding intent” 53 Ratio/importance of case issue case main “mere expression of words indicating a willingness to do an act” is not enough to create an undertaking “something in the nature of a commitment, generally, though not necessarily, upon which reliance can reasonably be said to have been placed” Browne’s word “I’m going to take you to the hospital” is not really an undertaking – it is more of a phrase rather than a binding commitment Ratio: An undertaking requires binding commitment and generally (but not necessary) reliance by the other party – just stating willingness to do something (just words) is not enough to create a legal undertaking. But then what would count as an undertaking if not a verbal commitment in such an emergency situation? Even if you could see his phrase as an undertaking, he did fulfill it because he did take her to the hospital where she was then pronounced dead (so he did fulfill his undertaking – just not in the way that might have been expected i.e. by calling an ambulance). Notes: III. R v. Peterson [2005] – legal duty to person under your charge (such as an elderly parent) Code: Facts: Issues: Decision: Reasons: s.215(1)(c): Everyone is under a legal duty to provide necessaries of life to a person under his charge if that person: (i) is unable, by reason of detention, age, illness, mental disorder or other cause, to withdraw himself from that charge, AND (ii) is unable to provide himself with the necessaries of life Arnold is elderly and has dementia, lives with his son Dennis The house is divided into units; Dennis had control over locking Arnold’s floor Arnold living in unhygienic conditions - not eating, would get lost, but he was also fiercely independent Dennis was told about community agencies but chose not to use them and didn't give Arnold food regularly Dennis convicted of failing to provide necessaries of life to Arnold Charged: failing to provide necessaries of life Was Arnold under Dennis’ charge under s.215(1)(c)? Arnold was under D’s charge. Dennis failed to provide necessaries of life. Reasons: (Weiler JA, MAJORITY) Offence provision in s.215(2) imposes liability on objective basis – “marked departure from the conduct of a reasonably prudent person having the charge of another in circumstances where it objectively foreseeable that failure to provide necessaries of life would risk danger to life or permanent endangerment of the health of the person under the charge of the other “ p. 278-79 How do you define being under someone’s charge? Being under someone's charge requires exercise of element of control by one person and dependency from the other person who is under the charge 54 Ratio/importance of case issue case main o Also consider relative positions of the parties and their ability to understand the circumstances (i.e. Arnold may not have understood his inability to care for himself because of his dementia) o Was there some sort of public acknowledgement in words or action of accused to suggest that someone was under charge/taking public responsibility for the other person said to be under charge Lists non-exhaustive criteria to support charge (indicators that in this case add up to finding that A under D's charge): o A was dependent and D knew this (ex: gave A food often) o S.215: family relationship can be part of why you think one person under charge o Dennis controlled Arnold's living conditions (locking out) and personal care o Power of attorney: legal recognition of charge o When Arnold was lost, neighbors would return to him - public acknowledgement that D was in charge o A unable to withdraw from other person's care because of his age and illness o A refused help from community organizations but could be argued that it was because of his dementia. DISSENT (Borins JA): Essentially agrees with reasons of majority, but says we need legislation Ratio: Notes: Being under someone’s charge requires exercise of element of control by one person and dependency from the other person that is under charge Autonomy of elderly interfered but you could argue that the autonomy of elderly could be questioned if you see a change in their behavior and if they are no longer able to take care of their own environment/food/clothing etc., then perhaps adult child living with them then has a duty of undertaking. 4) Voluntariness Basic principle: An act is only capable of constituting a criminal act when it is voluntary. There is willpower involved. An involuntary act is no act at all – it does not even fulfill the act requirement. It flows from behavior being unconscious or the person him/herself is unconscious Ex: physical reflex at a doctor where you accidentally hit him is involuntary – your leg could have spasmed while he was testing with a reflex testing hammer on your knee and so that would be an involuntary act Involuntary act: epileptic seizure Driving and you suddenly have a heart attack resulting in the car swarming – that would also be involuntary [Automatism – a sub category of involuntary act but we’ll do it later] – people who are in altered states on consciousness, usually because of some sort of mental disorder where they can do complex activities (such as sleepwalking) without realizing it. 55 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Why don’t we punish involuntary acts? Why is not counted as act at all? Lack of intent is a problem for sure (Ex. reflex hammer) but I also don’t even have the act so why not? The person hasn’t made a choice to do the action itself You can’t deter these types of actions because people have no control over it Voluntariness and Absolut liability An “absolute liability offence” is an offence that has no fault element – the act is all you need to be to guilty of offence (for ex: parking in a place where you’re not supposed to be parked – the act of parking in that place is all you need to prove the offence, not the intent) To convict the accused of an absolute liability, the Crown only has to prove the act element Because voluntariness is part of the act element, it is a requirement even for absolute liability offences (ex: someone stole your car and parked your car where it wasn’t supposed to be). Distinguishing Voluntariness and fault: I. H.L.A. Hart gives a useful definition of involuntary acts as “not subordinated to the agent’s conscious plans of action: they do not occur as part of anything the agent takes himself to be doing.” The law distinguishes lack of fault, for example lack of foresight of consequences, from true involuntariness For examples, in most cases firing a gun is a voluntary act whether or not you think you will hurt someone R. v. Lucki [1955] – acquittal for involuntary act of slipping on black ice Fact: Guy going super slow but slips on ice and hits the car coming from the other side Issue: Can Lucki be held responsible for this or was this act involuntary? Decision: Judge acquitted him for an involuntarily ending up on the wrong side of the road due to the black ice causing his car to slip Reasoning: Car skidded to ice (so out of his control) Driving appropriately for conditions (i.e. super slow) Ratio: A person who ends up driving on the wrong side of the road due to an involuntary act for which he is not to blame is not guilty of the act. Note Judge made mistake in reasoning by saying that Lucki wasn’t in control, it was involuntary, so he didn’t have mens rea and cant be convicted…. HOWEVER Voluntariness is internal to the act element, not fault element. So judge should have said that the act did not occur. 56 Ratio/importance of case issue II. case main R. v. Wolfe [1975] – reflex actions also involuntary – guy hits with a telephone Facts: Wolfe owns hotel Complainant not allowed in Wolfe's hotel, but he entered one night Wolfe asked him to leave and he would not, so Wolfe went to call police Complainant punched Wolfe, who turned around quickly and hit the complainant on the head with the phone receiver Complainant was cut on the forehead as result Wolfe charged with assault causing bodily harm Issue: Is Wolfe guilty of assault? Decision: Appeal allowed. Guilty verdict set aside, verdict of acquittal entered Reasons: Trial judge called Wolfe hitting complainant a reflex action but still convicted If reflex action, not voluntary Ratio: Reflex actions are involuntary, so no actus reus III. R. v. Swaby [2001] – guy driving unaware that passenger in his car has an unlicensed gun Code: Facts: Issue: Decision: Reasons: S91(3): Every one who is an occupant of a motor vehicle in which he knows there is a restricted weapon is, unless some occupant of the motor vehicle is the holder of a permit under which he may lawfully have that weapon in his possession in the vehicle, or he establishes that he had reason to believe that some occupant of the motor vehicle was the holder of such permit 1. Guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years; OR Guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction Facts: Police follow a car based on a tip - Swaby driving, J is a passenger J got out of the car and ran into a backyard, where police found a loaded, unregistered, restricted gun Accused convicted of "being an occupant in a vehicle knowing there was present an unlicensed, restricted weapon contrary to s. 91(3) of the Criminal Code" J testified that the gun was the accused's, and accused gave it to J to dispose of it Accused: gun was J's and he learned about it after arrest Accused appealed conviction Did the crown prove voluntary act here to ground criminal liability? Appeal allowed. Crown didn’t prove voluntary act – conviction set aside and new trial ordered to consider voluntariness. Section requires Crown to prove 1) occupancy in vehicle and 2) knowledge of weapon, but also prove that the coincidence of occupancy and knowledge was attributable to a voluntary act (even though statute doesn't explicitly state such a requirement) If one is in the car and then becomes aware of weapon, there needs to be a period of time where the individual can make a choice - if driver acts appropriately to get himself or the gun out of the car, there is no voluntary act 57 Ratio/importance of case issue Ratio: Notes: IV. case main (even though there may have been an overlap of both knowledge and occupancy, even for a very short time) Concern with possible scenario where Swaby found out if he was driving MacPherson JA (DISSENT): Swaby said he didn't know about the gun until after arrest, while J said he knew all along - no evidence as to whether he found out while driving so it wasn't necessary for judge to explain to the jury May need to have a reasonable opportunity to make a voluntary choice in some situations often happens in drug scenarios where you find out you are in possession of drugs – do you choose to call the police or keep it? Kilbride v. Lake - This case an example of an involuntary OMISSION (because failure to have the warrant). Facts: The accused was charged with having his car on the road without a current warrant of fitness He acknowledges that he parked his car at the time where there was a current warrant of fitness and walks away However, when he came back, there’s no warrant of fitness but a ticket instead. He argues that someone else could have removed it or it could have flown away. Issue: Can appellant be held guilty for something which resulted from a cause outside his control? Decision: Appeal allowed. No actus reas. Reasoning: At trial and appeal, lawyers argue whether an absolute liability offence where proof of the act is enough, or it is a mens rea/fault requirement act. Judges: we don’t even need to get into fault act – this is an issue of involuntariness. Ratio: “person cannot be made criminally responsible…. where there was some other course available to him.” If you had no choice of doing the act, then it is involuntary. 5) Causation Causation also part of the act requirement but always a requirement (unlike voluntariness of an act) causation one of the elements that must be proven by the crown Causation must be proven in offences that carry certain prohibited consequences “consequence crimes” – such as s. 222: “a person commits homicide when, directly or indirectly, he causes the death of a human being.” CAUSATION MUST BE PROVEN IN ALL HOMICIDE CASES (murder & manslaughter) BECAUSE OF THE PROHIBITED CONSEQUENCE OF THE ACT. 58 Ratio/importance of case issue I. Code: main other offences where causation must be proven include: Assault causing bodily harm Aggravated assault (wounds or maims disfigure the life of a person…. i.e. the consequence is that the person’s life is endangered, or body is disfigured) Willful damage to property (there actually has to be damage to the property) Arson Criminal negligence causing bodily harm Criminal negligence causing death Dangerous driving causing bodily harm (or death) Impaired driving causing bodily harm (or death) Generally, offences with more serious consequences are considered more serious and attract higher penalties (Such as death) Factual causation A mechanical, causal story What’s the factual cause of death (ex: gunshot wound) Legal causation Whether it is appropriate in the circumstances to hold the accused responsible for having caused the consequence. There is no question about factual or legal causation in straightforward cases where A shoots B. In other cases, there might be other factors contributing to the death, which makes death something like a freakish accident (ex: you don’t shoot a person but punch them in the face that suddenly causes their death because perhaps they had some underlying vulnerability). Both must be proven to prove causation The criminal code contains no general causation principles, but it does contain special rules applicable in homicide cases: See sections 222(5)(c), 224-226 General causation principles are found in common law. R. v. Smithers [1978] SCC – leading case on causation test (significant contributing factor outside the de minimis range) Facts: case s.265(1)(a): a person commits an assault when without the consent of another person, he applies force intentionally to that other person, directly or indirectly. s.222(5)(a): A person commits culpable homicide when he causes the death of a human being by means of an unlawful act. Smithers (a black teenager) subject to racial slurs by the deceased during a hockey game Smithers pursues deceased after game; punches him, who doubles over and while Smithers arm being held back by some people so he delivers a kick to the deceased’s stomach deceased vomits, aspirates on his vomit and dies found that aspiration occurred due to epiglottis malfunction (rare and unusual cause of death). 59 Ratio/importance of case issue case main not murder because death was not intended as a consequence charged with unlawful act manslaughter (s.222(5)(a)) [i.e. unlawful act of assault causing death] Issues: Was jury adequately instructed of whether they could find beyond reasonable doubt that kick caused the death? Decision: Kick was one of the contributing causes of death outside the de minimis (non-trivial) range, so Smithers found guilty. Reasoning: Dickson J: What is the test for causation? o "There was a very substantial body of evidence, both expert and lay, before the jury indicating that the kick was at least a contributing cause of death outside the de minimis range" The kick does not have to be the only cause of death or even the main cause of death, just one of the causes of death outside the de minimis range Given medical event that aspirating vomit is rare cause of death, argument would be that it's not the kick that caused death but the victim's malfunctioning epiglottis o Kick doesn't have to be the only cause! Illegal act doesn't have to be only cause of death but a contributing cause outside de minimus range o Malfunctioning epiglottis arguably broke chain of causation but it doesn’t matter because it was one of the causes of death Thin skull rule – take victim as he finds him, some frailty of the victim meant assault had worse consequences than it would have had without that frailty, still have to deal with the consequences that do come o does not mean the accused is not liable, even with the malfunctioning epiglottis (see p.311) Even if another person would not have died by the kick without the malfunction, Smithers is still responsible for what happened here Ratio: For unlawful act manslaughter, test of causation is a contributing cause of death outside the de minimis (trivial) range – low standard for causation Contributing cause of death that is not trivial Criminal law is harsh when it comes to causation! **General Smithers test for manslaughter and homicide generally, incl most murders, but special test for murder under s231(5) specifically** R. v. Harbottle 1993 – test for causation for 1ST degree murder: “substantial cause test” – ONLY FOR MURDER(sexual assault) II. s.231(5): Irrespective of whether a murder is planned and deliberate on the part of any person, murder is first degree murder in respect of a person when the death is caused by that person while committing or attempting to commit an offence under one of the following sections...(b) 271 (sexual assault) A woman and companion confine a woman and the companion sexually assaults the woman They then discuss ways to murder her 60 Ratio/importance of case issue III. case main Harbottle then holds down the legs of the victim while the companion kills the woman. Does holding down someone’s legs constitute as causing their death under s.231(5)? Yes. Guilty. A stricter approach to causation applies to first degree murder under s.231(5) Judge Cory: To be guilty of first-degree murder under s.231(5), an accused must have “committed an act or series of acts which are of such a nature that they must be regarded as a substantial and integral cause of the death.” (324) This is known as the “substantial cause test” only under s.231(5) the accused’s acts must be an “essential, substantial and integral part of the killing” (pg. 325) requires the accused to play a very active (usually physical) role in the killing – the accused was physically dominating the victim. this test is more demanding than the Smithers test that applies generally in homicide in its most favorable light of this stricter requirement for causation requirement under s.231(5) is because of the sentencing consequences of first degree. The problem under the facts of this case is that it does not apply to all first-degree murders such as planned degree murder it applies only under s.231(5). It seems like an easy case that Harbottle was definitely involved in the killing that he held the legs down. However, it is problematic for people who may have had a smaller contributory role in a killing but could still be categorized under first degree murder. R. v. Nette 2001 – significant contributing cause test: FOR ALL CAUSATION IN CRIM – START WITH THIS TEST FOR HOMICIDE BEFORE GOING TO HARBOTTLE TEST Woman bound to bed with cloth wrapped around her head after a robbery The cloth gets tighter and tighter and she eventually dies. Of course, he caused her death how did this case end up all the way up to SCC!! SCC – for the majority, Arbour J.: Distinguished Factual causation = cause of death in a medical, mechanical, physical sense Legal causation = whether the person should be held responsible in law Reaffirmed the Smithers test for causation in homicide (“a contributing cause of death, outside the de minimis range”), but reworded as….” Significant contributing cause” In Dissent, L’Heureux-Dube J. distinguished: “a contributing cause of death, outside the de minimis range” and “significant contributing cause” In her view, these two phrases do not have the same meaning. According to SCC, it means any contributing cause outside the de minimis range. 61 Ratio/importance of case issue case main In most/all cases in criminal law, if causation an issue you apply the significant contributing cause test. Then, If there is an issue that the accused might be guilty of first degree murder SPECIFICALLY UNDER S.231(5), that’s when you pull out the substantial cause test as an additional cause test when deciding if the accused is guilty of first-degree murder under 231(5). Even in Harbottle, you still have to start with the significant contributing cause test to establish first if the accused is guilty of murder and then if they’re guilty of murder under s.231(5) which is aggravated murder. You would also have to talk about other issues under s.231(5)….under Pare we talked about the meaning of while committing as a single transaction. You would also have to talk about that to prove if accused is guilty of first-degree murder under s.231(5). Intervening Cause: Chain of causation is from the accused’s act that goes over to a prohibited consequence (ex: death). Intervening cause question comes IN THE MIDDLE of the accused’s act and the prohibited consequence. The chain of causation WE are concerned with is the timeline that flows from accused’s guilt (not the intervening cause/person) to the prohibited consequence. Ex: If A caused B’s death and C was an intervening cause, talk about whether A’s act is a significant contributing cause to the death, NOT C’S intervening cause!!! Talk about C in relation to A and whether they break the chain of causation BUT not whether or not C is guilty – only focus on whether or not A is guilty – not C. The Code: Causation in Homicide: 1. Homicide: 222…(5) A person commits culpable homicide when he causes the death of a human being… (c) by causing that human being, by threats or fear of violence or by deception, to do anything causes his death. Ex: you run after a person with a knife but the person decides to jump out of the window. You caused their death under the Code, not them jumping out of the window. 2. Death that might have been prevented: 224 “where a person, by an act or omission, does anything that results in the death of a human being, he causes the death of that human being notwithstanding that death from that cause might have been prevented by resorting to proper means.” Ex: you shot a person and they didn’t die right away but they bleed out on the spot. The theme of the Code provision is to widen the scope provision and uphold the causal chain, even when you think it might be broken or there might be doubt. 3. Death from treatment of injury 62 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 225 “where a person causes to a human being a bodily injury that is of itself of a dangerous nature and from which death results, he causes death of that human being notwithstanding that the immediate cause of death is proper or improper treatment that is applied in good faith. Ex: the person you shot is taken to the emergency but there is some surgical error – in this case, the shooter still caused the death because he’s the one made the person end up in a hospital. 4. Acceleration of death 226 Where a person causes to a human being a bodily injury that results in death, he causes the death of that human being notwithstanding that the effect of the bodily injury is only to accelerate his death from a disease or disorder arising from some other cause. Ex: a person with a heart disease receives a heart attack during an assault and dies because of the heart attack, not the assault act directly. That wouldn’t break the causal chain and the person assaulting would have caused the death because it accelerated his death as the heart attack happened in THAT instant of the assault. I. R. v. Smith [1959] – English case about intervening cause From England court martial appeal court. Fight between English soldiers Victim stabbed twice with a bayonet – in the arm and the back (nobody noticed the back wound) His friends tried to take him to the medical station and dropped him twice on the way there The medical staff did not see he was in too much distress so he ended up not getting the best medical care – the best treatment would have been for him to get a blood transfusion, which the medical center did not even have a set up. Defense: bad medical treatment caused the death, not the accused. Court: there is no requirement that the accused’s unlawful act be the only cause of death – it does not relieve the accused of his act because of other intervening causes. Causation does not require that the criminal act is the ONLY cause of death Intervening acts must be overwhelming to make the operating and substantial cause/original wound “history” in order to make the intervening act the cause of death Issues: Did the stabbing cause death or did the intervening causes (dropping, bad medical care) alter the situation? Ratio: pg.340 “if at the time of death the original wound is still an operating cause and a substantial cause, then the death can properly be said to be the result of the wound, albeit that some other cause of death is also operation. Only if it can be said that the original wounding is merely the setting in which another cause operated can it be said that the death does not result from the wound. Putting it another way, only if the second is so overwhelming as to make the original wound merely part of the history can it be said that the death does not flow from the wound.” Ex: an overwhelming second cause could be a plane crushing the hospital and the stabbed guy dies. Or if he was recovering from the wound but doctors negligently gave him antibiotics that he knew he was allergic to and ends up dying to it (Jordan case); in this case the court acquitted the accused but that could go either way. Another hypothetical of an 63 Ratio/importance of case issue II. case main overwhelming second cause would be SARs epidemic breaking out in the hospital that forces the stabbed person who was recovering and ready to check out back in the hospital and die because of SARs – that would break the causation. You could apply Canada’s s. 225 – death from treatment of injury -to the above case. R. v. Blaue [1975] English case – woman refusing blood transfusion and bleeds out because of wound An English court case. 18-year old woman was a Jehovah’s Witness Blaue came to her house and when she refused sex, he stabbed her She was rushed to the hospital and required blood transfusion or her organs would go into failure She refuses blood transfusion on religious grounds, signs a consent form that she is refusing treatment and she dies. Defense: stabbing did not cause the death; the decision by the victim to not take the treatment that caused the death was an intervening cause that broke the chain of causation. You could say that there is an independent choice (by the victim) that is causing death and maybe that should relieve Blaue of responsibility. English court argues no, she bled out from the stab wound; her refusing the blood transfusion is just a cause of death Court also argues that this is kind of like “thin-skull” example – you take the victim not just with their physical features and diseases but also their religious beliefs. How would Blaue be decided in Canada? It’s just an application of the thin skull rule – so Canadian court would support it. S. 224: Blaue fits perfectly within s. 224 – she was entitled not to resort to proper means This case would have been decided the same way in Canadian courts. If there is any argument that Blaue didn’t cause the death, the only thing that they could do is bring a Charter challenge against the legislation that this is too broad. III. R. v. Maybin – FIRST CASE TO GO TO FOR INTERVENING CAUSE ANALYTICAL AIDS Big things that you would need to mention is intervening cause, signif contrib test, foresee and indep acts Leading Canadian case on causation and intervening causation. Maybin brothers beat up a victim and leave him on the pool table and leave The bouncer comes up and delivers a punch to the unconscious victim lying on the pool table before throwing him outside. 64 Ratio/importance of case issue case main The victim died of head injuries – not sure whose punch exactly caused the death. That leads to causation problem that works to the benefit of the bouncer – he’s not guilty of manslaughter because there is a very reasonable doubt that the victim did not die of the bouncer’s punch so he is off the hook. But how are the Maybin brothers different? Unlike the bouncer, they were a significant cause of the death Either they beat him up and caused the death in the literal sense with their own fist or They put him in a situation where he was in vulnerable situation. Bouncer different and not a significant cause of death because: Either his punch contributed to the death or It did nothing to the guy because he was already going to die. The court suggests an approach to causation: Factual causation – generally apply the “but for” test. “but for” the assault of the Maybin brothers, the victim would not have died or would not have been in a situation of vulnerability such as this that would have resulted in his death. Legal causation – determine whether the accused should be held accountable for the consequences – intervening causes go here. The basic test is still “significant contributing cause” Looking at the link between accused’s act and the consequence - is there a significant link between the two? Two analytical aids (which means they don’t need to be passed – they’re just aids for the significant contributing cause test) can help determine whether an intervening act breaks the chain of causation: 1. Reasonable foreseeability – was the general nature of the intervening act and the risk of harm foreseeable at the time of the accused’s act? Reasonably foreseeable that others at the bar could get physically involved? Yes – which means that the Maybin’s brothers act was a significant contributing cause of the death. 2. Independent acts – was the intervening act so independent of the accused’s act that it should be regarded as the sole cause? Or were the acts so connected that they can’t be said to be independent? Overwhelming cause from Smith’s – that the second cause was so overwhelmingly independent of the first cause (Ex: falling plane example). 65 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 5. The Fault Requirement 1) Introduction The fault element will vary with the act – ex: negligent vs. guilty mind Actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea – “there is no guilty act without a guilty mind” This maxim expresses the idea that criminal offences require some fault element Mens rea could be different from one act to another It could be a useful umbrella category Fault includes in the form of negligence whereas mens rea is more in the mental mind of the accused. Fault element usually mirrors the act element. What the fault elements are you can look at the act elements. Fault element broadly reflects the moral blameworthy that goes with the act. What the fault element is will vary with the offence There is no single state of mind intended by the term mens rea Subjective/objective distinction of fault: Subjective fault: The accused must actually hold a particular blameworthy state of mind – e.g. knowledge of some fact Associate with the concept of mens rea, the sense that it is guilty mind. Concerns what was actually in the mind of the accused at the time of the act. Objective fault the accused must have failed to live up to the standard of reasonable person – criminal liability generally requires a “marked departure” from that standard associated with the concept of negligence – sometimes you’ll see the phrase negligence crimes (which means they carry an objective fault) concerns what the accused “ought to” or “should” have known – e.g. objective fault is lower on the fault requirement – easier for the crown to prove and isn’t as blameworthy. That doesn’t mean that objective fault doesn’t carry serious sentencing – if dangerous driving leads to death for example that could carry sentencing. Proving Mental State: “the state of a man’s mind is as much a fact as the state of his digestion” (Bowen L.J., p. 362) The accused’s state of mind is a fact that can be proven by evidence Sometimes, the accused testifies directly about what he or she was thinking at the time of the act (direct evidence) 66 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Often, state of mind can reasonably be inferred from the circumstances (circumstantial evidence) Ex: When you stab someone several times, anyone can infer that it would kill a person. So even if the accused say he didn’t intend to kill, you can tell from the circumstantial evidence of the act (i.e. repeated stabbing) would kill a person and so that proves his state of mind as guilty and with the intent to kill. Mental state usually inferred from circumstantial evidence Fault element: I. The fault element, or mens rea, has “nothing to do with the accused’s system of values.” (R. v. Theroux at 363) A person knows the consequences of their act, even if they don’t think it’s wrong Mens rea is not about what the accused thought of the moral value – like it doesn’t matter if the accused person doesn’t think it’s wrong – criminal law is perfectly capable of defining that. The blameworthy state of mind will often be inferred from the act itself, or from the circumstance. Presumption = a permissible inference, presumption means that the conclusion must follow and that’s not really the state of law – it is just a permitted inference. R. v. Beaver [1957] – KNOWLEDGE required for subjective mens rea – guy had cocaine but thought it was powdered sugar Two brothers sell heroine to an undercover cop. Accused says that they thought it was some sort of sugar. Issue: Is possession of a drug an absolute liability offence, or must there be knowledge as part of the subjective mens rea of the accused? Even if he did think it was sugar of milk, he actually think it was heroine for his possession Accused: it is important to knowing whether it was sugar milk for his being proven guilt What if the accused possessed heroin but thought it was sugar? Possession requires “KNOWLEDGE of the character of the forbidden substance” (pg. 371). Dissenting judge: problem in legislation (pg. 368): The language seems to demand absolute liability – it just says anyone who has possession of any drugs is guilty of offence. Majority: knowledge is required to mens rea. Absolute liability problematic because punishes people who are actually free of moral blameworthy and are completely innocent. Ratio: To be guilty of possession, must have knowledge that you are possessing something and of the character of the thing you possess -possession is not an absolute liability offence (All drug offences require subjective mens rea) Problem with absolute liability: convicts morally innocent people, which is against a major principle of the criminal law Can't be guilty of possession without knowledge of the character of the forbidden substance 67 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 2) Regulatory offences I. R. v. City of Sault Ste. Marie [1978] – strict liability fault for regulatory offenses City charged with polluting the creek by contracting out the cleaning to another company. Whether the City would also be guilty of pollution offences They weren’t responsible for Cherokee’s offence (who was hired as an independent contractor to deal with the pollution) J. Dickson (not a fan of absolute liability): Distinction between criminal and regulatory offences He confirms criminal offences require subjective mens rea – however, not always true because sometimes subjective mens rea isn’t required for criminal offences. Regulatory offences – not true crimes but rather public welfare offences that prohibit certain acts such as speeding and polluting waters Strongly urged by the crown that absolute liability for public welfare offences which was not accepted: Pros: Faster and more efficient for the crown to not required to prove fault and make them pay for consequences If people know they won’t be able to use a fault element loophole to get out of liability, then they’ll uphold higher standards to prevent being fallen to absolute liability. People have bought in to being regulated therefore we should be strict with how those are upheld by the regulatory bodies. It’s not a criminal offence so people don’t see you as a criminal so therefore you don’t have to be as worried as you would be for a convicted; penalties and stigma is lower. Cons (J Dickson): It punishes morally innocent people – if someone has done everything they could to meet the regulation and still pollution occurs it is unfair to hold them to absolute liability It also doesn’t deter people based on a loophole – if people will still be held absolutely liable no matter how much care they take, why would they hold higher standards? No administer efficiency - you can’t punish morally innocent people just for the sake of efficiency. Judge Dickson: Strict liability: crown proves act and accused can raise defense of due diligence (accused on a balance of probabilities can prove non-negligence and be exonerated). An opportunity to give duly diligent people to show that they were perhaps innocent Defense has the onus to prove All regulatory offence: default would be the strict liability offence subject to exceptions. Strict liability is another option for fault element. 68 Ratio/importance of case issue case main There could also be a different fault element for regulatory offence which is in the legislation or you can Ratio: Any regulatory offence will be an offence of strict liability by default, unless the language of the legislation clearly indicates it is either subjective or absolute liability, or through historic interpretation shows that it should carry some other fault liability. II. R. v. Wholesale Travel Group Inc. – difference between regulatory and criminal offences Justice Cory: Suggests ways to distinguish regulatory and criminal offences Prohibited wrongs are wrong because regulation prohibits it (Ex: driving on the left side of the road in Ontario is wrong in Ontario but wouldn’t be a wrong in Canada), whereas criminal offences are those acts that are so morally wrong and unacceptable to the public Regulatory offences: induce compliance of the public through following stop signs, abiding traffic rules etc. for the protection Criminal offences are more focused on past attacks – also more culpable and more imprisonment False advertisement comes more under regulatory offences because it is not so wrong in itself and rather aims to protect the public. Justifications for imposing higher fault requirement for criminal offences than for regulatory offence: Licensing justification – when people participate in regulatory activities, they enter a sphere where they know they must adhere to certain standards/regulations. Ex: you don’t have to drive a car in Ontario but if you choose to do so, you must abide by the regulations that bind all drivers on the road. Regulations are often there to protect powerless and disadvantaged people in society – ex: post industrial Revolution there were crazy working conditions. Regulations came into play by placing high standards in favor of vulnerable people (i.e. workers, and to prevent child labor). Charter Standards for Fault: Are there some fault requirements that are constitutionally required? Person who buys the baking soda but is actually heroine – that is so offensive to our ideas of FPJ A fault element can be constitutionally required under s.7 of the Charter: The principles of fundamental justice require a minimum level of fault to be proved for an accused to be guilty of certain offences. In these cases, the charter sets constitutional minimum fault requirements The BC Motor Vehicle Act Reference sets the Charter minimum for regulatory offences. (pg. 398) Driving while prohibited an absolute offence under the Act and carried a minimum penalty of imprisonment That is problematic for FPJ – for example, they checked everything they could to make sure their license was suspended but for some reason it still was so that would be unfair to hold such an innocent person morally responsible. 69 Ratio/importance of case issue case main It is a PFJ that the innocent must not be punished An offence that combines absolute liability and the possibility of imprisonment violates s. 7 of the Charter Therefore, strict liability is the Charter minimum fault requirement for any offence punishable by imprisonment. Three options of fault: 1. Absolute liability 2. Strict liability (part of objective liability) open to accused to prove due diligence. 3. Subjective liability What does due diligence require? III. Due diligence – taking reasonable care – means different things in different contexts, for example: Making only reasonable mistakes Taking reasonable safety precautions Levis v. Tetreault – due diligence can’t be passive – need to take reasonable precautions Missed deadline for not registering vehicles properly Waiting for the notice to come in the mail for a reminder so they were being duly diligent. SCC held that doing nothing is not due diligence – pure passivity is not due diligence. 3) Murder Difference between murder and manslaughter: if you mean to kill someone= murder. If you didn’t intend to kill someone= manslaughter. The fault element is what separate murder and manslaughter. Homicide = causing human death. (homicide itself is not an offence) culpable homicide is an offence = murder (subjective fault) and manslaughter (criminal negligence causing death). Manslaughter is the default rule for culpable homicide, unless it can be proven it was murder. Culpable homicide – the actus reas of murder and manslaughter. (every murder and manslaughter must be a culpable homicide). Usually in murder, there is a very obvious unlawful act – ex: assault. It being an assault is an illegal act and if that causes death, then we’re in culpable homicide. s. 222: “A person commits homicide when directly or indirectly…” murder usually prosecuted under: s.229: culpable homicide is murder a). where the person who causes the death of a human being 70 Ratio/importance of case issue case main i). means to cause his death, or ii). Means to cause him bodily harm that he knows is likely to cause his death, and is reckless whether death ensues or not. s. 229 is the fault element for murder. s. 229 (b) – transferred intent Culpable homicide is murder… b). where a person, meaning to cause death to a human being or meaning to cause him bodily harm that he knows is likely to cause his death, and being reckless whether death ensues or not, by accident or mistake causes death to another human being, notwithstanding that he does not mean to cause death or bodily harm to that human being. s.230: [defines murder] first question, are you even guilty of murder? If yes, then move on to next question – was it first degree or second degree? I. II. The Simpson Case [1981] – jury instruction for PROPERLY instructing jury on subjective intent for murder (s.229(a) & (b)) Attempted murder case. Fault element to cause death also required for attempted death. Judge charged jury with fault element for murder but problem with the charge: PG. 425: Stated the fault element in an objective way (i.e. ought to have known) Rather, should be in subjective way (DO NOT CITE THIS CASE FOR FAULT ELEMENT – FOR THAT USE THE CODE) use this case to stress that jury instructions need to be subjective. R. v. Edelenbos [2004] – no need to give definition of likely – be careful in language used for SUBJECTIVE FAULT (has to include knowledge AND INTENT) Accused admitting to sexually assaulting and then strangling victim to death so we know at the very least it is culpable homicide but he defends he did not intend to kill her so not murder only strangled her to stop her from screaming. Trial Judge: What likely means – pg. 426 “likely means more than a possibility…by using the word likely the legislators were trying to get at killings where the risk was subjectively…” COA: Definition of likely should not be given not because it is wrong but rather unnecessary If probabilities arise, then ask the parties how submissions should be made to the jury, not the judge just deciding to read it without it being necessary. Maybe important to charge the jury what is likely to cause death if only it is necessary but not in all causes. So no definition of likely because unnecessary in this case. So even though error of giving definition of likely, doesn’t change/affect the verdict. Has the COA phrased the test correctly in para. 29 (pg. 430)? No!! COA should have stated it as “he knew it was likely” not “that was likely” to 71 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Essence of the fault element is subjective intent which HE WOULD KNOW cause death – DO NOT OMIT INTENTION AND KNOWLEDGE, WHICH IS THE ESSENCE OF THE FAULT ELEMENT FOR MURDER Constructive murder – a killing that in the eyes of the law is deemed to be murder, even though the normal fault requirement under s. 229(a) is absent. I. There are such sections of constructive murder– ss.229(c) and 230 All these held to be unconstitutional – abolished in Canada What is the constitutional minimum fault requirement for murder? Vaillancourt v. R [1987] – murder under constitution requires at least objective foresight Dealt with s.213(d) [now s. 230(d))] since repealed: Accused and accomplice committed armed robbery in pool hall Accomplice had gun and shot and escaped and never found Accused charged with murder as an accomplice to the murder Vaillaincourt insisted on taking away the bullets from his friends before the robbery to minimize risks Convicted by jury on s.213(d) which was later numbered s.230(d): Homicide was murder if two conditions held: Homicide occurred while the accused was committing or attempting to commit a specified offence (e.g. robbery, arson, rape, kidnapping, forcible confinement, breaking and entering) Death ensued because the offender used or had a weapon while committing the offence or when fleeing afterwards. But s. 213(d) explicitly did not require the accused to intend to cause death or even to know that death was likely S.213(d) allowed a murder conviction where the ordinary fault requirement for murder (in s.229(a)) was not fulfilled (i.e. intention and knowledge) Justice Lamer: Charter analysis: S.7 – fundamental justice to be followed to prevent unfair deprivation of life This section indicates that some crimes carry such a high stigma and so a fault element reflecting the nature of the crime will be constitutionally required. Pg. 439: “whatever the minimum mens rea for the act or the result may be……” It wouldn’t be allowed for parliament to just redefine all manslaughter as murder because it would be capturing people whose moral blameworthiness does not reflect the severity. This murder provision did not require death to be even objectively foreseeable. Murder should always require subjective foresight of death (Lamer in obiter) Ratio: Vaillantcourt hold only that s.7 and the principles of fundamental justice require at least that death must have been objectively foreseeable before a person can be convicted of murder. 72 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Section 213(d) did not require even objective foreseeability of death, so it violated s.7 II. R. v. Martineau [1990] – constructive murder – ALL OF S.230 UNCONSTITUTIONAL – s.7 of Charter requires subjective, not objective foresight of death to be guilty of murder Shot the two to death s.7 also require that murder requires subjective mens rea Convicted of second degree murder (another form of constructive murder – s.213(a)/now s.230(a) which is still in the Code). Under s.230(a), homicide is murder if two conditions hold: Homicide occurs while the accused is committing or attempting to commit a specified offence (e.g. robbery, arson, sexual assault, kidnapping, forcible confinement, breaking and entering) Death ensues from bodily harm intentionally caused by the accused for the purpose of facilitating the offence. CJC Lamer: Held for the majority that the principles of fundamental justice under s.7 require subjective foresight of death for a murder conviction Reasons the PFJ require fault element should be at least of subjective foresight is because stigma of murder conviction is very high and the penalty is the highest too – so there has to be as a matter of fairness some proportionality between the stigma/penalty on one hand and the moral blameworthy on the other. Under Martineau: All parts of s.230 are unconstitutional S.229(c) is unconstitutional at least in part Dube (dissenting): It does require death will be at least objectively foreseeable – the person intends to cause bodily harm and it has to be in the context of subjective mens rea. If we look at people who harm people in the We can just use Vaillancourt here and the objective foreseeability is met under this court. Why parliament might have chosen to define these particular killings as murder not manslaughter: Fault element doesn’t entirely define how a crime is Policy arguments in favor of limited constructive rule in s.213(a) She says there will be still stigma for manslaughter Even if murder has a higher stigma, these people who have caused bodily harm/death deserve the stigma of causing death in an act – this is just misplaced compassion She thinks it’s a valid deterrence for parliament to have exceptionally strict rules for people committing crimes such as theft, kidnapping, sexual assault because homicide usually in these contexts. Accidental killings won’t be covered (this section on the other hand requires intentional killing) 73 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Unlawful Object Murder: After Martineau, it’s clear that s.229(c) of the Code is unconstitutional at least in part: 229. Culpable homicide is murder…. (c) where a person, for an unlawful object, does anything that he knows or ought to know is likely to cause death, and thereby causes death to a human being, notwithstanding that he desires to effect his object without causing death or bodily harm to any human being. The unconstitutional part is the ought to know language – not allowed under Martineau. Degrees of Murder: When convicted of murder, it’s either first-degree or second-degree. By default, your murder is second-degree murder (just like the default for culpable homicide is manslaughter). Section 231(1) of the Code provides: Murder is first degree murder or second-degree murder Whether a murder is first or second-degree murder only arise where the accused is guilty of murder Where the accused is charged with first degree murder, two questions must be decided: 1. Is the accused guilty of murder? 2. If yes, should it be classified as first-degree murder? Always keep those questions separate and answer in that order. Classification: First-degree murder sentencing is much more severe than second-degree sentencing They both automatically lead to imprisonment for life. (s.235) Difference in parole for the two degrees – s.745 Serve 25 years of sentence before eligible for parole under first-degree Serve 10 years of sentence before eligible for parole under second-degree What classifies murder as first-degree murder (which has an act and fault element). Aggravating factors/circumstances turn second-degree to first-degree murder Stop using the language of actus rea (act) and mens rea (fault) for classifying murder – aggravating circumstance is the language you use First degree murder includes: “planned and deliberate” murder: s. 231(2) What exactly does this mean? Murder of specified victims (on-duty police, prison workers, etc.): s. 231(4) Murder “while committing’” specified offences of illegal domination (hijacking, sexual assault, kidnapping, hostage taking, etc.): s. 231(5) S. 231(7) 74 Ratio/importance of case issue I. II. case main R. v. Smith [1979] – leading case for test for planned and deliberate murder: Third person breaking windows and comes around the house to find accused and victim pointing guns at each other Accused shot the victim in the arm; accused took a couple of minutes to reload his shotgun and shoots the victim several more times until the victim dies. Jury finds him guilty of first-degree degree – no doubt that it is murder. Question is if it was planned and deliberate such that jury was entitled to find him guilty of firstdegree murder Court said that no evidence to support that finding This was a sudden impulse killing and so was not planned Since no evidence of planning, the jury should not have been even given the option of making a finding the Smith was guilty of first-degree murder. First-degree murder has to be BOTH planned AND deliberate. Planned and deliberate mean something more than intentional Planned means arranged beforehand – the result of a scheme or design previously formulated by the accused Deliberate on the other hand means considered and not impulsive. Smith hadn’t arranged to kill before they got to the farmhouse. Issues with this: technically he took the time to reload the shotgun in his car. His friend asked him what are you going to do? The accused at the time was formulating his thoughts, wasn’t he? Court said it was not enough time to devise and thus was considered impulse, not planned. This case kind of on the line between first-degree and second-degree murder. Mention Smith on an exam where someone quickly deciding to kill. Pg. 465: planned and deliberate language “carefully thought out, not hasty or rash”, “slow in deciding”, “cautious”. R. v. Nygaard and Schimmens [1989]: - 1st degree murder if bodily harm LIKELY causing death, even if not intending death Can you combine s.231(2) with murder under culpable homicide with intention equalizing planned and deliberate? You can have planned and deliberate murder even where there wasn’t an intention to cause death if their planned involved causing bodily harm that they knew would likely cause death. Ex: in this case, crown combined s.31(2) – planned and deliberate and s.229(a)(ii) – intent for bodily harm because accused planned and deliberate the causing od bodily harm which would likely result in death, so charged with first-degree murder (i.e. beat up the victim with a baseball bat)/ Plan and deliberate murder is the main category for first-degree murder. III. R. v. Collins [1989] – murder of police officers on duty murder of specified victims defined by occupation, such as on-duty police. They put themselves at risk of violence, so the intention of the code is to protect them. 75 Ratio/importance of case issue case main court ruling: accused had to know or appreciate the risk that the victim could have been a police officer – it would be so unfair to not require such knowledge which would make it unconstitutional murder “while committing”….s.231(5) – make connections from Pare and causation that applies from Harbottle case. 4) Subjective mens rea Statute requiring subjective mens rea: looking for words like… “meaning to” “willingly, willfully” “intentionally” “knowingly” 76 Ratio/importance of case issue I. II. case main R. v. H. (A.D) [2013] – child abandonment code provision, Walmart washroom Code: 218: every one who unlawfully abandons or exposes a child who is under the age of ten years, so that its life is or is likely to be endangered or its health is or is likely to be permanently injured, (a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years; or (b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding eighteen months. Facts: Woman gives birth to child in walmart bathroom – thinks he’s dead so leaves him there. Other patrons come find the baby – also think he is dead until he moves. Issue: What is the fault requirement that applies to this offence? Decision: Fault is SMR - common law presumption that all true crimes require SMR applies. Appeal dismissed. Accused acquitted. Crimes are presumed to have a SMR requirement. S.218 requires a subjective fault requirement SCC Cromwell J (majority): the trial judge was wrong to think that the offence required objective fault element when it actually had subjective mens rea. the presumption does not require all offences be treated as subjective mens rea – you need to look at the legislation to look for hints if there are any hints for if it’s a subjective mens rea. but the text is ambiguous too so the common law presumption of subjective mens rea is not displaced. he also relies on the language of abandoning or exposing as meaning “subjective mens rea”. Minority (concurring): this is a way to protect children from any foreseeable danger – imposes a societal minimum standard of conduct if we take this as subjective mens rea, then we have to take a lot of other things into account such as if she was intoxicated, young and uneducated. he still agreed thought that the acquittal should be affirmed. is this departure from the standard of care of what the reasonable person thought? others thought the child was also dead so she didn’t really depart from that standard and thus should have been acquitted. R. v. Buzzanga & Durocher [1979] – definition of intent as conscious purpose or foresight of prohibited consequence. defines intention as the actor’s: conscious purpose to bring about a consequence or subjective foresight that the prohibited consequence is substantially certain to occur 77 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 2 French guys charged with promoting willful promotion of hatred against French – but was it willful if they meant it to be satirical? this is definitely subjective mens rea but is there the intent to spread hate because their pamphlet was meant to be satirical? there promotion of hatred was not willful so new trial order. willful promotion of hate requires intention or knowledge. they wanted to create some sort of uproar/controversy but not by promoting hatred against the French specifically – rather they wanted to create sympathy for the French causes by pointing to the hatred against to the French. Recklessness: III. IV. recklessness a type of subjective mens rea that actually requires that the accused had ACTUAL AWARENESS of risk (different from negligence which is an objective mens rea). Sansregret v. R [1985] – definition of recklessness as a subjective fault this case defines recklessness as a subjective standard Mcintyre J: “it is found in the attitude of one who, aware that there is danger that his prohibited conduct could bring about the result prohibited by the criminal law, nevertheless persists, despite the risk.” recklessness meaning it is the conduct of “one who sees the risk and who takes chance.” less blameworthy than intent because you intend the consequence of death whereas in recklessness you just it as a possible risk. case further hold that willful blindness is also a subjective state of mind it is tantamount to knowledge a person who is willfully blind is treated in law as a person with knowledge willful blindness exists where the accused is aware of the need for inquiry and deliberately fails to inquire in order to preserve ignorance. ex: you’re in Venezuela, which is known for growing cocaine. somebody at the airport gives you 5k to take back a suitcase. you accept without inquiring what is in the suitcase because you think that if you don’t know, you can just that as defense that you didn’t know it had cocaine in it. THAT’S WILFUL BLINDNESS if you were just super naïve and didn’t know then it could be considered negligence still because any reasonable person should be careful to not take something from a stranger at the airport. R. v. Briscoe [2010] – willful blindness definition as a subjective fault described as “deliberate ignorance” IT INVOLVES “AN ACTUAL PROCESS OF SUPPRESSING A SUSPICION” (such as not opening the suspect) Accessory after the fact – ex murder of your friend’s worst enemy on tv. friend comes over covered in blood and you don’t inquire or suppress your suspicions and let them stay in the basement – that’s willful blindness coz you suppress your suspicions and inquiries. 78 Ratio/importance of case issue V. case main R. v. Blondin [1971] – willful blindness imported 23 pounds of hashish in a scuba tank. Blondin gets caught at the airport all he knew was there was something illegal in the tank but not exactly what. so does that meet the fault requirement of the offence? think back to Beaver: essence of possession requires knowledge as well. Blondin knew it was illegal but not a drug to be convicted of trafficking hashish, Blondin had to know or at least suspect that the substance in the tank was a narcotic. there could be a reasonable inference that there could be some sort of narcotics, at which point you could still say he was willfully blind (even if not knowing it was hashish in particular). he did not have to know it was hashish it would be sufficient to find, in relation to a narcotic, mens rea in its widest sense.” but knowing it was “something illegal” would not be enough – he had to know it was some sort f drugs. 5) Objective Fault Accused’s conduct measured against the standard of a reasonable person Crown proves objective fault element beyond a reasonable doubt Exception: strict liability offences, where fault is objective and there is a reverse onus (defense of due diligence). Language indicating objective fault – “ought to”, “reasonable care/steps”, “good reason”, “due care and attention” Examples of objective fault offences: Failure to provide necessaries of life, dangerous driving, careless use of a firearm, endangering aircraft safety 79 Ratio/importance of case issue case main OBJECTIVE FAULT CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE OFFENCES Examples: ONLY S.220 & 221 OFFENCES TEST: “marked and substantial departure” from SOC OTHER OBJECTIVE FAULT CRIMES Examples: failing to provide necessaries of life, careless use of a firearm, dangerous driving TEST: “marked departure” from SOC REGULATORY OFFENCES UNLAWFUL ACT MANSLAUGHTER (UAM) Examples: Strict Liability offences EXAMPLE: R. V. CREIGHTON TEST: simple negligence with reverse onus – defense of “due diligence” TEST: additional fault requirement “objective foreseeability of the risk of BODILY HARM which is neither trivial nor transitory Criminal negligence ALL objective fault offences usually use "marked departure from reasonable standard" as level of fault *Note: criminal negligence is just one section under negligence crimes/objective fault crime category The definition of “criminal negligence” appears in s. 219 of the Code: 219(1) every one is criminally negligent who (a) in doing anything, or (b) in omitting to do anything that it is his duty to do, shows wanton or reckless disregard for the lives or safety of other persons. (2) for the purposes of this section, duty means a duty imposed by law. I. II. The ONLY associated offence provisions appear in s. 220 and s. 221. criminal negligence offenses only exist when there is some bodily harm (s.221) or death (s.220) caused. If an act wanton or reckless but no one gets hurt, then no criminal negligence charge O’Grady v. Sparling [1960] -criminal negligence historically subjective fault Historically, criminal negligence was an offence that required some level of subjective fault. R. v. Tutton & Tutton [1989] – discussion of when to use objective vs. subjective fault Facts: 80 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Accused charged with manslaughter in relation to death of their son Alleged that they caused death of their son by criminal negligence by omitting to provide necessaries of life - failed to provide insulin and obtain timely medical help Knew their son had diabetes, knew how to control his sugar levels and did so for a time, but they were part of a religious sect believing in faith healing Stopped giving him insulin - he was saved the first time, but he died after the second time Trial: convicted of manslaughter This case is liability based on omission - duty is that they are parents, under s215 have duty to provide necessaries of life to child (in this case, life-saving medical treatment) Issue: What level of fault is required for criminal negligence causing death? Decision: New trial. Court split 3:3 on fault element Reasons: McIntyre J: (2) -CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE =OBJECTIVE We don't get answer about fault element in this case - split Fault requirement is the same for criminal negligence whether it was an act or an omission (all 6 members of the Court are in agreement on this) Criminal negligence should require objective fault The provision focuses on conduct of accused rather than mental state or intention - conduct has to objectively show wanton or reckless disregard, not fault in accused's own mind What is criminal under this section is negligence - "negligence is the opposite of thoughtdirected action" (clearly not thinking things through clearly, so how could we require subjective fault) What is punished is not the intention but the "consequence of mindless action" Test for showing wanton or reckless disregard: test of reasonableness and proof of conduct "which reveals a marked and significant departure from the standard which could be expected of a reasonably prudent person" Departure from SOC of reasonable person is negligence in a civil standard For criminal neg, it's not just any departure from SOC - you have to do something that is VERY unreasonable, not just unreasonable/not living up to standard Idea is not to criminalize the whole law of tort - trying to mark out narrower, morally blameworthy area that deserves punishment Note: recklessness is NOT the same as reckless disregard Mistakes: Unreasonable mistakes don't provide a defense - for Tuttons to say we made mistake and thought he didn't need insulin Question becomes, is that mistake reasonable or not - if unreasonable, it departs from standard of reasonable person under objective standard Example of the welder: welding in confined space, asks owner if anything flammable around and owner says no, so he welds and causes explosion Not liable because it was reasonable to rely on what owner told him - this is a reasonable mistake which could provide a defense Lamer J: CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE=OBJECTIVE Agrees that standard is objective but says it needs to have "generous allowance" for taking into account factors unique to the accused, such as age, education, mental development Concerned that we are laying out standards that some people won't be able to meet Wilson J (3): CRIMINAL NEGLIGENCE= SUBJECTIVE 81 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Says basing criminal negligence in objective fault is essentially making it an absolute liability offence That is incorrect - absolute liability has no fault element at all! Very strict penalties, given ambiguity in section we should hold accused to subjective standard, ESPECIALLY BECAUSE PARLIAMENT HASN’T MADE IT CLEAR IN STATUTORY LANGUAGE THAT IT IS OBJECTIVE “it requires some degree of awareness or advertence to the threat to the lives or safety of others or alternatively a willful blindness to that threat.” Mistaken beliefs don’t have to be to reasonable to exonerate the excused but rather look carefully to see if person is being willfully blind Tuttons had a mistaken belief that their son didn’t require insulin so perhaps no subjective mens rea – but were they willfully blinding themselves? The doctor did warn them after all… they had a perception of the risks because mom had educated herself in diabetes Ratio: Inconclusive 3:3 split in 6-member court - 3 talking about objective standard, 3 talking about subjective standard -gives arguments as to why you would use objective or subjective standard to understand the context III. R v. Creighton [1993] – objective standard requires marked departure from SOC Facts: The accused, a companion and the deceased consumed a lot of alcohol and cocaine The accused knew a lot about drugs, he was expert drug user Deceased consented to accused injecting cocaine in her arm, she overdosed Companion wanted to call ambulance but accused said no and intimidated him The two cleaned the apartment of fingerprints and left Accused charged with unlawful act manslaughter (unlawful act = trafficking drugs, injecting drugs into the deceased’s arm) Issues: Is the fault requirement for unlawful act manslaughter subjective or objective? Decision: Objective fault for manslaughter, accused is found guilty Reasoning: Lamer (concurring) NOT THE LAW: Take into account personal factors which would change the standard of care Ex: Creighton was an experienced drug user so the standard of care would be higher Could also be lower depending on person’s knowledge, experience, age, incapacities such as illiteracy, lack of knowledge etc. McLachlin (majority/5): The “marked departure” test applies to objective fault crimes generally Objective fault crimes have a “single, uniform legal standard of care…subject to one exception: incapacity to appreciate the nature of the risk which the activity in question entails.”:” unlike Lamer who would take into consideration more factors All objective fault crimes require marked departure of standard of care of reasonable person (later confirmed in Beatty) 82 Ratio/importance of case issue case main In general, this is true But exceptions: crim neg requires marked and substantial departure (higher) Unlawful act manslaughter also different, has its own test Ratio: Unlawful act manslaughter requires objective fault Generally, don't consider personal characteristics except for incapacity, but of course we still consider what the reasonable person would have done in the circumstances (welder example) nge of personal characteristics such as inexperience IV. R. v. Beaty [2008] -negligent driving in torts but not criminal negligence if no “marked departure” from SOC of dangerous driving Facts: Accused driving truck Went straight instead of turning and went into oncoming traffic- hit a car, killed three people Was driving at speed limit and not drunk, but may have had sun stroke Momentary lapse of attention Charged with three counts of dangerous driving causing death Trial said negligence was not sufficient to be criminal negligence – civil negligence for sure because only a few seconds of negligent driving but doesn’t meet criminal standard for dangerous driving CoA said negligence constituted criminal offence of dangerous driving Issues: How does the objective test apply in this dangerous driving case? Decision: SCC – reinstated trial decision. Momentary lapse of attention is not marked departure Reasoning: Dangerous driving is an objective fault crime and the objective standard is modified in 2 ways: 1. Standard is a “marked departure” Criminalizing a person should not be done lightly only when the reasonable conduct of a driver is way off the standard should criminalize it look at the DEGREE of negligence as well 2. Exculpatory defenses can be considered (ex: unexpected happenings while driving such as heart attack, seizure, retina detached) Prof thinks these are just examples of involuntary behavior Elements of dangerous driving: Actus Rea: 249(1) Every one commits an offence who operates (a) A motor vehicle in a manner that is dangerous to the public, having regard to all circumstances, including the nature, condition, and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that at the time is or might reasonably be expected to be at the place. Beaty had the actus rea – due to the failure to confine his car to his own lane. Mens Rea: 83 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Beaty lacked objective fault of “marked departure” from SOC of reasonable driver (was driving on speed limit and only a momentary lapse of attention) Instead, guilty of provincial highway regulatory offence for careless driving instead He had civil negligence (so tort damages) but not enough to warrant a “marked departure” required for the criminal offense of dangerous driving. Need a “marked departure” for objective fault because of Charter implications for imprisonment Ratio: For dangerous driving cases specifically, momentary lapse of attention is not enough to meet criteria of “marked departure” to have objective fault for criminal negligence. V. R. F (J) [2008] -difference between “marked & substantial departure” vs. “marked departure” Distinguished between: “marked and substantial departure” for criminal negligence only under s.219 VS Other objective fault crimes requiring just “marked departure” PROF’S DRIVING EXAMPLE TO DIFFERENTIATE BETWEEN THE TWO: NO CRIMINAL OR CIVIL LIABILITY: Driving a car and someone runs in front of you CIVIL LIABILITY (like BEATY): Momentary lapse of attention – careless driving under highway traffic law of province MARKED DEPARTURE (UNDER S.249(1)(a)): Overloaded truck driving too fast in rainy conditions, crosses red light and crashes into another care. MARKED AND SUBSTANTIAL DEPARTURE (UNDER S.219): Intoxicated driving with lights off in the on-coming traffic lane to scare people and you hit someone. Unlawful act manslaughter (UAM) UAM based on a predicate offence: 84 Ratio/importance of case issue I. case main Accused must have committed some other offense that causes death Usually assault, like in Jobidon but could be something else Need to prove following to charge UAM: Predicate offence The predicate offence caused death (in terms of principles of causation ACT ELEMENT of manslaughter, and its fault element – either subjective or objective) Fault element of UAM (see below) R. v. Creighton [1993] – leading case on UAM and test for it. Recall: man injected cocaine into someone he was doing drugs with, that person ended up dying Predicate offence here was not assault because she consented to cocaine, but rather it was drug trafficking Issue: What is the fault element for the offence of unlawful act manslaughter? Decision: Court divided 5-4 on whether objective test for unlawful act manslaughter did not require reasonable foresight of DEATH (Lamer CJ, minority) but reasonable foresight of BODILY HARM (McLachlin J, majority) Reasoning: The fault requirement for unlawful act has two parts: i. Fault element of the predicate offence (i.e. drug trafficking), which must: Involve a dangerous act, Not be an absolute liability offence, and Be itself constitutionally valid ii. The ADDITIONAL fault requirement for manslaughter “objective foreseeability of the risk of bodily harm which is neither trivial nor transitory, in the context of a dangerous acts. “ Minority: this is a low fault requirement for UCM which results in imprisonment/heavy penalties majority: not true because court considers blameworthy of accused on a case by case basis Majority: there is a lower social stigma than murder minority: not true because still damaging to a person’s social status after going through the whole process Minority: death has to be foreseeable under Charter requirements for such a harsh penalty majority: the whole point of UAM is that it’s not murder so will have a lower fault requirement and penalties. Also, no constitutional requirement to have fault mirror exactly the act element (death, in this case) so acceptable to have fault requirement for only foreseeability of bodily harm. Majority: under the thin skull rule, any time someone imposes nontrivial bodily harm, then death is inherently foreseeable so that gets blanketed under foreseeability of bodily harm. Terrible consequence of death demands more than a lesser offence – it has to be manslaughter because of consequence of death Aggravated forms of assault DEFINITION (not offence) OF AGGRAVATED ASSAULT: 85 Ratio/importance of case issue case main s. 268 (1) every one commits an aggravated assault who wounds, maims, disfigures or endangers the life of the complainant. under R. v. Godin, SCC 1994, aggravated assault requires: (ACTUS REA): an assault that wounds, maims, disfigures or endangers life, AND (MENS REA): objective foreseeability of bodily harm (drawn from Creighton) assault CAUSING bodily harm is controversial some provinces only require an assault that actually causes bodily harm (with no fault element related to the harm) others (including Ontario) say that harm must be reasonably foreseeable. 6. Rape and Sexual Assault sexual offenses were overhauled in 1982 the offence of “Rape” was repealed and replaced with “Sexual assault” for both offences, lack of consent is an element of the offence that must be proven by the Crown rape was nonconsensual intercourse however, sexual assault offence is much broader and covers other physical touching such as groping and is gender neutral. in other words, there is a “defense of consent” in sexual assault and rape cases 1) Rape laws in context – historical rules around rape, granted spousal immunity (yuck) Historical rules specific to rape cases (see numbered points): rape is a gender issue in the sense that, rape/sexual assault typically committed by adult men and typically against females. although it is not uncommon to be committed against males but is less common than female victims. women with disabilities experience a higher rate than normal women. indigenous women also much more likely to experience assault than non-indigenous women commonly held beliefs/myths: sexual assault is not prevalent and there are just false allegations. however, not true. myth that rape involves a stranger in a dark alley – there are definitely some rapes that happen that way. however, most happen by family members or acquaintances they know. another myth that even if raped by family member, not so bad. however, again untrue because just as psychologically damaging to be sexually assaulted by a close/loved/trusted family member. 86 Ratio/importance of case issue case main long history in law of victim-blaming to hold the complainant responsible for being sexually assaulted (ex: the way she’s dressed, certain types of women got raped and “good girls” didn’t…prevented many women from coming forward due to that stigma). rape was really an offence against the father or husband and thus girl might become less marriageable/less pure and so sexuality treated as a “property” of the husband/father. 1. prior sexual history of the complainant: was routinely admitted and said to be relevant to: did she consent? if she had sex with the accused before was relevant was she a credible (believable) witness? chastity went to the credibility of the woman. rape shield laws limit the sexual history of evidence. 2. doctrine of recent complaint rape victims were expected to report the rape: at the first available opportunity, and spontaneously reporting late was a reason to doubt the truth of the report 3. corroboration for women and child complainants their testimony in a rape case had to be corroborated by independent evidence implicating the accused Alan Young, “When Titan Clashed” defense lawyers looking for psychiatric and therapeutic access of the complainant to attack their credibility a trend in the 90s. two ways of understanding this trend: i. latest version of thinking all rape allegations are false and just discrediting the women by turning it into a trial of the victim ii. think about the fact that there might be something unique about sexual assault trials because there is no other evidence – just that of the complainant’s stacked up against the accused. harder to prove beyond a reasonable doubt when there are only two witnesses – the complainant and the accused. not surprising then that defense lawyers find new ways to discredit the complainant. the old rape offence: not illegal to rape your wife once married, consent was always there rape was limited to sexual intercourse (penetration) we know the crown must prove non-consent non-consent is a circumstance element – part of the act element is there a corresponding mental element? accused’s subjective awareness of non-consent yes – this mental element is reflected in the defense of sexual assault as being consensual. 87 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 2) Crimes of sexual assault I. the sexual assault provisions in the Code have a three-tier structure, ascending order of penalty and seriousness: 1. sexual assault: s.271 2. sexual assault with a weapon, threats to a third party, causing bodily harm, or multiple perpetrators: s.272 3. aggravated sexual assault: s.273 three-tiered system adopted to de-emphasize sexual assault as a sexual assault and more as an act of violence of which the sexual is one part of. no spousal immunity R. v. Chase [1987] – leading case for definition of sexual assault Issue: how to determine whether assault is sexual or not facts: complainant a 15-year old girl whose neighbor came over while she was playing with her brother the accused groped her breasts and said, “I know you want it”. New Brunswick court convicted as normal assault case, not sexual assault because it did not involve any genital parts. SCC- CONVICTED the accused McIntyre (majority) defining sexual assault: Ratio: a sexual assault is an assault “committed in circumstances of a sexual nature, such that the sexual integrity of the victim is violated” the sexual nature of the contact is determined objectively, on the standard of the reasonable observer factors to be considered include: the body part touched the nature of the touching the surrounding situation or circumstances accompanying words or gestures, including threats the intent or purpose behind the touching, including sexual gratification 3) Consent and mistaken belief Consent in Code & vitiation of consent: 88 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Applies to all assaults Applies only to sexual assaults (s. 271, 272 & 273) Definition of consent none 273.1(1) Where consent vitiated 265(3) 273.1(2) Note: other common law limits on consent beyond the above row – ex: Jobidon Mistaken belief in consent 265(4) 273.2 Defense of Mistaken belief in consent: the complainant may not have consented, but the accused thought the complainant did consent it negates the mens rea requirement of subjective fault. Section 265(4): Commanding judge to instruct the jury where mistaken belief is an issue, to consider presence or absence of reasonable grounds for the mistaken belief. Limitations on this defense: applies in a “situation of ambiguity” (R. v. Davis) some limits are in the Code (s.273.2 and s.265(4)): no defense of mistaken belief without reasonable steps no defense of mistaken belief based on self-induced intoxication, recklessness, or willful blindness juries must be instructed to consider reasonableness. additional limitations from Ewanchuk (see below) include: a mistaken belief in consent must be a belief that consent was expressed or communicated a belief that no means yes, or that silence, passivity or ambiguous conduct equals consent is no defense. once the complainant says “no” the accused is on notice and must be sure consent is communicated before proceeding. I. R. v. Ewanchuk [1999] – meaning of consent, no such thing as implied consent, fear may result in compliance but there still can be no consent so no need to look at vitiation Facts: She met accused for essentially a job interview, went into his trailer and she believed she was locked in 89 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Accused initiated a number of touching incidents, each got progressively more intimate although the complainant said no and stop every time Trial judge found the complainant to be credible BUT acquitted on the basis that even if that happened, it wasn't a sexual assault Subjectively, in her mind, she didn't consent and was fearful But he also found that she was trying not to seem afraid, which is consistent with what she said Because she concealed her fear, her subjective feelings are irrelevant and consent should be implied at law because of her conduct Acquittal on basis of "implied consent", upheld by COA Issues: What is consent? Whether consent was vitiated by fear? Held: SCC imposes a conviction Reasoning: (Major/ MAJORITY) Goes over elements of sexual assault: i. Actus reus, 3 parts: (i) Touching – objectively determined (ii) Sexual nature – objectively determined (accused does not need to have any mens rea with regards to the sexual nature of the touching) (iii) Absence of consent – subjective, determined by complainant’s subjective internal state of mind (what was in the mind of the complainant at the time of the sexual touching) If court finds she did not subjectively consent, consent cannot be implied by the circumstances Trial judge was wrong to find implied consent she either consented or not, there is no third option defense of implied defense does not exist there is no consent at all do not have to consider consent vitiated by fear because no consent at all Subjective question of why she submitted - the fear doesn't have to be reasonable for consent to be vitiated on this basis consent shown in 2 ways: the complainant in her mind wanted the sexual touching to take place OR the complainant had affirmatively communicated by words or conduct her agreement to engage in sexual activity defense of mistaken belief of consent is a mens rea requirement ii. mens rea of sexual assault: (i) intention to touch (ii) subjective mens rea regarding non-consent (here, concerned with the mind of the accused accused knew, was reckless to, or willfully blind to fact that complainant was not consenting) Only by looking at what the other person expressed can we determine what was in the mind of the accused continuing sexual conduct after someone has said no is reckless conduct where there is mistaken belief in consent, then acquittal 90 Ratio/importance of case issue case main defense is limited; accused must believe the complainant communicated consent (not enough to think that the complainant thought it in her head) Consent can be communicated by words OR conduct To rely on defense of mistaken belief of consent, they have to rely on some II. affirmative consent from the complainant (in the form of words or conduct) silence is not a defense “no means yes” belief is not a defense Once complainant say no, accused must be very sure of consent before continuing to engage - complainant is able to change their mind, but accused is going to have to be very sure of an expression of consent before pressing on Can't "test the waters" with further sexual touching once someone says no APPLICATION Complainant said no Accused didn't raise defense of mistaken belief of consent, but if he had it was clear there was no air of reality R. v. A. (J) [2011] – consent in advance for sexual activities, esp. if unconscious? Facts: Complainant unconscious during some sexual acts that she had consented to Issues: can a person consent in advance to sexual activity that takes place while the person is unconscious? And If she consented in advance to the sexual touching, whether the consent was still valid once unconscious. Decision: impossible for an unconscious person to satisfy requirement even if expressed advance consent because consent is in the MIND of the person (Ewanchuk) at the time of EACH ACTIVITY so sexual activity with an individual incapable of consciously evaluating whether she is consenting is not consensual within the meaning of the code. Reasoning: McLachlin (MAJORITY/6) Ongoing, conscious consent is required by Parliament - requires complainant to be conscious throughout the entire sexual activity and agree to each activity as its happening S 273.1(1) – consent definition – "in the sexual activity in question" means that consent has to be given for each activity, rules out broad advance consent S 273.1(2)(b) – no consent if incapable of consenting to the activity (may arise from unconsciousness) Protects from sexual exploitation Protects right to ask partner to stop at any time Consent is actual subjective consent in the mind of the complainant AT THE TIME of the sexual activity (Ewanchuck) Issue here is actus reus consent Question for actus reus is whether the complainant was subjectively consenting in her mind – not required to express her lack of consent or revocation of consent for the actus reus to be established 91 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Fish J dissent: Issue: not whether unconscious person can consent (which they can’t he agrees with majority), but whether a conscious person is allowed to consent to sex acts during a brief period of unconsciousness Nothing in code to say that Parliament put exception for advance consent or about timing of consent The code does not preclude advance consent from conscious person that carries through brief period of unconsciousness consent can be revoked, true that revocation not possible during unconsciousness, but suggests that consent is operative until revoke (carries through unconsciousness) - can revoke before or when you regain Policy arguments: If we're trying to protect people's sexual autonomy, isn't that regressive? Why police people’s consensual, private sex lives? (dissent) Kissing a sleeping partner would be sexual assault – absurdity (dissent) No it wouldn’t because that’s not as big a deal as sexual integrity being questioned during unconsciousness – need to protect vulnerable people (majority) On balance, criminal law needs to protect these people “de minimis non curat lex” the law does not care for small or trifling things Prof agrees with majority, despite sexual autonomy argument - need to protect vulnerability of unconscious people Ratio: definition of consent for sexual assault requires the complainant to provide ongoing, conscious consent. Consent means conscious agreement of consent of every sexual act in a particular encounter. 7. Incapacity 1) Age Criminal Code for child under twelve lacking capacity to be held responsible for criminal acts: s.13.: No person shall be convicted of an offence in respect of an act or omission on his part while that person was under the age of twelve years. problem with this rule: some mature 11-year-olds vs. immature 12-year-olds who commit homicide. proceedings different for youth criminal justice (under 18-year-olds). 2) Mental disorder S.16 of the Code: The accused is not criminally responsible by reason of mental disorder if: i. The accused committed the act “While suffering from a mental disorder” 92 Ratio/importance of case issue ii. case main “that rendered the person incapable of…” a. “appreciating the nature and quality of the act” or b. “knowing that it was wrong” Section 2 of the Code defines “mental disorder” as “a disease of the mind”. Leads to a verdict of not criminally responsible – which results in psychiatric detention until deemed fit by the facility to be released. Harder part is showing that the mental disorder made the person INCAPABLE of appreciating the nature and quality of the act or knowing that it was wrong. I. Cooper v. R. [1979] – leading case on defense of MENTAL DISORDER, disease of mind definition Facts: He had history of psych problems, strangled female friend to death Accused charged with murder of patient at psychiatric hospital Because of mental illness, may not have understood danger that he could kill his friend when choking her At trial, defense of insanity not raised by accused but judge still put it to jury because he thought defense was raised on the evidence (discussion of psychiatric history) Issue: Was there an evidentiary basis to put defense to the jury? Was there a basis on which jury could find accused was suffering from mental disorder that would prevent him from appreciating nature and quality of act or knowing it was wrong? Note: this criteria has not changed today! Decision: Trial judge was right to put defense to the jury, but he didn't explain it properly. New trial Reasons: Dickson J (5) meaning of “disease of the mind” is a question of law (for the judge) whether a particular disorder or disease is also a question of law so overall meaning of it and specific diseases like schizophrenia are disease of mind also to be decided by law – i.e. judge whether the accused was in fact suffering from the condition is a question of fact (for jury) Dickson CJ defined disease: “in a legal sense “disease of the mind” embraces any illness, disorder or abnormal condition which impairs the human and its functioning, excluding however, self-induced states caused by alcohol or drugs, as well as transitory mental states such as hysteria or concussion. in order to support a defense of insanity the disease must, of course, be of such intensity as to render the accused incapable of appreciating the nature and quality of the violent act or of knowing that it is wrong. underlying all of this discussion is the concept of responsibility and the notion that an accused is not legally responsible for acts resulting from mental disease or mental defect.” more difficult test is usually the incapacity. what it means to appreciate the nature and quality of the act: appreciating something is deeper than knowing it. 93 Ratio/importance of case issue case main appreciating requires emotional awareness and understanding of the consequences of the act, not just the physical act. Notes: Not hard to get client to be found to have disease of the mind, but harder to show the incapacity part of the defense 3) Automatism Reverse onus on defense to prove it Defined in Rabey as: “automatism is term used to describe unconscious, involuntary behavior, the state of a person who, though capable of action is not conscious of what he is doing. It means an unconscious involuntary act where the mind does not go with what is being done.” Sources of automatism & defenses: i. Internal Cause = mental disorder automatism (MDA)– ex: sexsomnia NCR that may result in indeterminate psychiatric detention ii. External Cause = sane (non-mental disorder) automatism – ex: blow to the head Can get a clear acquittal I. Rabey v. R [1977] – anger/rage/psychological blow not analogous to external cause of automatism of a blow to head – psychological blow must be in extraordinary events to be automatism Facts: Ms. X thought of Rabey just as a friend while Rabey was infatuated with Ms. X he had taken a large piece of rock from the lab and hit her with the rock a couple of times and strangled her Ms. X was not gravely injured and recovered soon after Rabey apparently at the time thought he had killed her and ran to someone in the hallway – some sort of physical signs of being in a weird state he claims he doesn’t remember anything he claims he was in a state of automatism due to his amnesia where he couldn’t remember anything. defense wants to say that psychological blow due to reading the letter that shut rabey’s mind off on how ms. X thought of him. suggestion is psychological blows are analogous to physical blows of getting hit in the head external cause. crown: he was in extreme state of rage – important distinction because that’s not automatism or a mental disorder because you can still be acting voluntary. Further, lack of memory was due to blocking out afterwards – not because of amnesia. it’s okay if they have flashes – but to claim amnesia would be to not remember at all. 94 Ratio/importance of case issue case main claim of amnesia is necessary for automatism claim – but not a strong claim because of so many people using amnesia to lie Issue: Should his defense have been non-insane automatism or mental disorder automatism? Decision: San automatism not available. New trial Reasoning: TWO CENTRAL QUESTIONS: 1. is the condition the accused claims to have suffered a disease of the mind? (I.E. In Rabey, is a dissociative state a disease of the mind?) question of law for the judge 2. does the evidence establish that the accused was in that state at the time of the offence? (was Rabey actually in a dissociative state as claimed?) question of fact for the jury Rabey’s dissociative state (assuming it existed) must have been caused by mental disorder distinguish automatism flowing from an external cause, and automatism flowing from a cause internal to the accused: automatism from an internal cause = mental disorder automatism (MDA) automatism from an external cause = non-mental disorder automatism (Sane automatism – blow to the head) and “the ordinary stresses and disappointments of life…do not constitute an external cause.” sane automatism can only arise from a “psychological blow” in cases of “extraordinary external events [that] might reasonably be presumed to affect the average normal person.” for example: being in a serious accident without being physically injured seeing a loved one murdered II. R. v. Parks [1992] – OVERTURNED BY STONE – sleepwalking, acquitted under sane automatism Facts: Parks was seriously sleep-deprived – due to personal issues and loss of job One night he “slept-drove” on the 401 for 20 min to his in-laws’ house murders his mother-in-law and injures father-in-law afterwards he went to the police station and said he killed two people and was at the time holding a knife and cut his hands completely to the bone might suggest automatism defense of sleep-walking crown appealed all the way up to the SCC Issues: Is sleepwalking sane or mental disorder automatism? Decision: appeal dismissed, trial judge did not err in leaving jury with defence of sane automatism rather than that of mental disorder because it was shown that sleepwalking is not disease of mind. Sane automatism was a valid defense here Reasoning: 95 Ratio/importance of case issue case main (Lamer, for the Court on this point) sleep-walking is a form of sane mental disorder automatism all 5 defense experts concluded sleepwalking experts: Parks personally had a history of sleep disorder, including in his family experts: violence during sleepwalking very rare but… experts: the risk of recurrence violence was very small experts: only thing you can do is practice good sleep practices. thus, right to give him a full acquittal on the basis of sane automatism. error in Lamer’s reasoning: if the experts say sleepwalking is not a disease of the mind, then there should be acquittal. (for the law – i.e. judge – to decide if something a disease of the mind. La Forest (concurring): is sleepwalking sane of mental disorder automatism? a question of law, not solely determined by psychiatric evidence: “the legal community reserves for itself the final determination of what constitutes a ‘disease of the mind.’ this is accomplished by adding the ‘legal or POLICY COMPONENT’ to the inquiry.” two approaches to the POLICY COMPONENT: 1. the continuing danger theory (mental disorder if continuing to show signs of danger to protect society; sane automatism if no recurrence danger) 2. the internal cause theory (ex: Raby – was this dissociative state caused something internal to Raby or external) both reflect concerns about recurrence and public safety internal cause is the dominant theory, but it is an analytical tool and not an overarching test in addition, wider policy concerns should be considered: floodgates concerns (if start giving people full acquittal on sleepwalking and psychological blows then is it opening it too wide?) but not easy to feign sleepwalking brain activity test and family history can’t be feigned for specifically sleepwalking but could be true for other psychological blow automatism which can be feigned – ex: Rabey automatism is easy to feign Ratio: Sleepwalking is not a mental disorder/disease of the mind. Note: Here, default seems to be sane automatism until there is evidence of MDA, but this is overruled by Stone, which changes presumptive rule to MDA III. R. v. Stone [1999] – START WITH THIS CASE WHEN DEALING WITH AUTOMATISM – presumption of automatism as MDA Facts: 96 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Wife was verbally abusive to Stone – said many insulting things to him, threatened to divorce him, said she had already falsely reported to police that he was abusing her He was in a car with his wife He felt a whoosh sensation, and lost contact with reality When his eyes focused again, he was staring straight ahead and holding a knife He stabbed her 47 times He hid the body, fled to Mexico He admitted to stabbing his wife, surrendered to police But he wanted to use defense of sane automatism - psychological blow automatism that caused him to snap in response to abuse Raised defenses including insane automatism, non-insane automatism, and alternatively provocation Trial judge found evidence of unconsciousness throughout the commission of the crime (evidentiary foundation for some type of automatism) but ruled that the defense had laid an evidentiary foundation for MDA, but not sane automatism Ultimately convicted of manslaughter Issues: Should this be sane automatism or MDA? Did Stone have a right to have his sane automatism defense to the jury? Decision: Verdict of manslaughter by trial judge upheld, who was also correct in instructing MD automatism because no extraordinary external event that triggered sane automatism RATIO: For defense of automatism, we start from presumption of MD automatism and defense will have to show it is not. Also, reverse onus is on defense to prove automatism and sane automatism. Reasoning: (Bastarache/ MAJORITY) Case of psychological blow automatism, kind of like Rabey Confirmed automatism is a defense because it negates the voluntariness of the actus reas and while in ordinary circumstances crown bears burden of proving voluntariness, in automatism case the burden is on defense to prove automatism on a balance of probability to the trier of fact – Reversal of burden of proof This harmonizes automatism with two related defenses, which also have reverse onus: Extreme intoxication, akin to automatism Mental disorder under s.16 In automatism cases, judge decides two things: Step 1: decide whether the defense of automatism is properly at issue and thus should be put to the jury: For this, we need two things: an assertion of involuntariness AND expert evidence to indicate person was in state of automatism Just being angry or rage doesn’t get you even close to the assertion of involuntariness – rather, it has to be something where you lose touch with reality Automatism is a rare defense Factors to be considered when automatism needs to be proved: Severity of the triggering stimulus (minor the trigger, the less likelihood of automatism) Corroborating medical history and of bystander witnesses Evidence of a motive Step 2: If automatism at issue, is it MD or sane automatism? Presumption that it's MDA, and the accused has burden of coming up with evidence to show that it should be sane automatism rather than MDA Take holistic approach to decide between the MD and sane automatism: 97 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Internal [md] vs. external [sane] cause theory Continuing danger (fundamental question of whether society needs protection from accused and thus needs to be subject to psychiatric detention under MD NCR regime of the Code) Thin line between sane and MD – if high risk of recurrence, then MD. If no danger of recurrence, then sane automatism. Policy concerns of being easy to feign, floodgates etc. Worried about opening floodgates because of how easy it is to feign in some instances (like Rabey) The more senseless the act looks, the more likely automatism will be accepted. Binnie J dissent: There was evidence to support that accused was not conscious and was in a state of automatism Stone was sane and did not have a MD, according to medical experts, so why leave it as a matter of law to avail him of only MD automatism and not sane automatism? Sane automatism should not have been taken away from jury because he was entitled to it – only plausible defense Onus of voluntariness on Crown – burden of proving that he was not in state of sane automatism Doubts usefulness of internal cause theory Rejects idea that we can presume mental disorder, unless an extreme external cause can be shown IN AUTOMATISM AREA, don't use test from Cooper to determine mental illness. Just look at holistic approach from Stone Note: this case says automatism will mainly be put into MD automatism pool, which didn’t exist in Parks. IV. R. v. Luedecke [2008] – sexsomnia guy – how to respond to automatism claims Facts: 98 Ratio/importance of case issue case main L at a party and had sex with the complainant while “sleep walking” Turns himself later to the police when he finds out someone was sexually assaulted at the party Had a history of abnormal sleep patterns (parasomnia) and had sex while asleep with his gfs in the past. Experts say parasomnia/sexsomnia not a disease of mind – just need to practice good sleep hygiene. Trial judge acquitted on sane automatism defense from Parks But Parks, has been overturned by Stones. Issue: Whether “sexsomina” was properly classified as mental disorder automatism? Decision: L found NCR under MD automatism and detained for a short while but released after assessment Reasons: apply the Stones analysis internal cause theory: L had a genetic condition and family history of sleepwalking AND…. Doherty JA outlines “a comprehensive response to automatism claims”: i. Pre-Verdict - when deciding whether to find NCR of full acquittal: Focus on social defense – where there is a risk of recurrence, that will almost always lead to an NCR verdict ii. Post-Verdict Focus on individual assessment of the individual’s dangerousness and only be detained if dangerous. Doherty further clarifies why medical experts saying not a disease of mind is of little value to the legal question medical experts are driven by moral intuition to get rid of blameworthiness whereas legal question doesn’t decide moral blameworthiness but rather if accused is a threat to society and needs to be deterred. non-mental cases of automatism will be limited to very rare cases where accused can point to a specific external event that precipitated that event, can demonstrate it is unlikely to reoccur, and show that the event could have produced a dissociative state in an otherwise “normal” person ex: unanticipated or unusual reaction or blow to head would be clear non-mental cases of automatism. 4) Intoxication 99 Ratio/importance of case issue I. case main R. v. Daviault (1994, SCC) – extreme drunkenness is defense for general intent offences; later removed by Parliament for violent crimes, Charter Minimum Facts: o o o o o o o o Accused went to acquaintances’ house, had 7 or 8 beers, brought large bottle of brandy Accused threw her on bed and sexually assaulted her, then got dressed and went home to bed Didn’t remember anything Expert testified that his blood alcohol level was very high and would have caused death or coma in a normal person Expert said Daviault might have suffered from amnesia automatism – alcoholic blackout where acts are involuntary and have no memory of them afterwards Expert evidence went uncontested because Crown didn’t bring own expert to counter this Mere fact that Daviault said he doesn’t remember is separate from voluntariness – had to not know what you were doing at the time to be in automatism state Trial judge acquitted here b/c of rule from Bernard – accused was extremely intoxicated, so had a reasonable doubt about whether he could form the intent of the offence Cory J (+3): o o o o o o o Upholds distinction between specific and general intent offences Explicitly adopts reasons of Justice Wilson from Bernard – Her reasons become the law in Daviault Intoxication can be a defense to general intent where intoxication is so extreme it violates the Charter and allows a person to be convicted even though the Crown has not proven mens rea for the offence (required by presumption of innocence) – just intending to become drunk is not the same as intending to sexually assault someone Dufraimont: sometimes Cory goes too far Cory says there is no rational link between intoxication and crime Dufraimont: There is a rational link, it’s a fact But yes, just being intoxicated isn’t a crime “Substitute mens rea” is a drastic violation of s. 7 and 11(d) of Charter and can’t be saved under s. 1, no pressing objective/need to violate the Charter here, and no rational link btw drunkenness and violence Charter minimum Requires at least giving defense of intoxication for general intent offences where the accused was intoxicated to the point of automatism known as defence of “extreme intoxication” Reverses burden of proof, and it’s acceptable to put burden on accused Accused has to show extreme intoxication based on a balance of probabilities Similar to defence of automatism and defence of MD We don’t have to be worried about requiring this Charter minimum b/c drunk defences will still be rare and still only applies to general intent offences where drunkenness is extreme 100 Ratio/importance of case issue case main o II. Floodgates argument not convincing b/c in jurisdictions where drunkenness defence is allowed, it’s still rarely successful o Dealt with this as negating mens rea of the offence, but all analysis would apply if you discussed this in terms of actus reus too b/c if the person is drunk to the point of automatism, then there’s no voluntariness and actually no act that’s why we have to have this defence so that Crown has to prove both actus reus and mens rea where there’s a doubt about these things Sopinka J (+2, dissent): *Dufraimont likes the dissent’s view o There is blameworthiness here and mens rea broadly speaking is supposed to reflect moral responsibility, and people who get themselves so drunk that they do violence to other people are morally responsible for that perverse result to use doctrine of mens rea to say someone is not responsible in that situation o Everyone accepts intoxication is a defence for specific intent offences, which is taken into consideration in sentencing and person can be punished for lesser offences R. v. Jensen – constitutionality of s.33.1 for being valid as limiting extreme intoxication defense to only non-violent offences with general intent Facts: The appellant was charged with murdering his roommate by stabbing her sixteen times. He admitted killing her, but asserted his extreme intoxication merited an outright acquittal, or at worst a conviction for manslaughter. He claimed an intoxication-induced blackout akin to automatism. Yet uncontradicted Crown evidence showed: far from being trance-like, he concealed the murder weapon that night; far from a total blackout, he made inculpatory statements the next day, showing he remembered much more about this killing than he let on at trial. The appellant testified he didn't recall killing Lynda but didn't dispute killing her Flaws in his story, inculpatory statements, selective memory History of drinking/pills so how much could it really affect him waking up the next morning in bed beside Lynda, seeing that she was dead; getting out of bed and pouring a beer; gradually realizing that he may have caused some kind of tragedy; Covering up after himself Weakness in defense pharmacy expert - Dr. Rosenbloom was erroneously permitted to testify beyond his qualifications (see Issue 7). While he had a pharmacy doctorate and had taught medical students and psychiatrists, including about alcohol and drugs effects, he has no degree in pharmacology, psychiatry, psychology, toxicology or medicine. Never assessed him either but argued that because the appellant took alcohol and Valium, he was an automaton, too intoxicated to form murder or manslaughter mens rea. He said that substantial drinking can lead to blackouts. Taking Valium, including in the amount the defence claimed, can contribute to this. It can cause memory loss for the period after the drug is taken. This can lead to a person not knowing what they are doing and not afterwards remembering what they had done. 101 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Issue 6: Does Code s. 33.1 as applied here violate the appellant's Charter ss. 7 and 11(d) rights? Daviault doesn't render s. 33.1 unconstitutional, even though Parliament's approach differs from Daviault, because: Daviault considered a Charter attack on a common law rule, not legislation. The Daviault Court gave Parliament no deference. In contrast, here appellant attacks new legislation. Hence, judicial deference to Parliament applies Section 33.1 is aimed at the pressing and substantial objective of protecting the innocent public from violence perpetrated by people who voluntarily get themselves extremely intoxicated Section 33.1 is rationally connected to that objective, as was the broader common law rule attacked in Daviault. Parliament's legislative record included expert psychiatric advice on the relationship between intoxication and violence. Oakes’ test: Section 33.1 minimally impairs Charter rights for the preceding reasons and since: (a) under s. 1's minimal impairment requirement, Parliament needn't adopt the least intrusive law imaginable. It is sufficient for Parliament to have, as it here amply had, a reasonable basis for concluding that it had minimally impaired Charter rights consistent with effectively promoting its pressing societal objectives (Canadian Newspapers Co. v. Canada (Attorney General) [1988] 2 S.C.R. 122 (S.C.C.) at paras. 17-20). – (b) Section 33.1 meets Charter s. 1's proportionality requirement for the preceding reasons, and because, in the important aim of protecting the lives and safety of the innocent public, Parliament has taken the minimal step of not treating brutally destructive conduct such as the appellant's as blameless. Issue 7: Did the judge err in law in admitting material parts of defence pharmacy expert Rosenbloom's evidence? – III. proposed Rosenbloom as an expert in three areas: (i) absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination of drugs and alcohol, (ii) effects of drugs and alcohol on the human body; and (iii) actions, interactions and adverse effects of drugs and alcohol in healthy subjects and patients with illnesses. – The judge erred in letting Rosenbloom testify in three areas. First, he was wrongly permitted to opine on what constitutes consciousness, and on whether a person in a blackout is in a state of consciousness. The Crown submits that this question more properly fits within psychology or psychiatry - And memory - if seasoned drinkers are more likely than non-seasoned drinkers to experience blackouts from drinking, he said yes because non-seasoned drinkers may well choose not to have it happen again R. v. Daley [2007] – 3 INTOXICATION DEFENSES – START WITH ADVANCED INTOXICATION According to Daley, there are three legally relevant degrees of intoxication: 102 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 1. Mild intoxication – reduces inhibitions and can increase aggression, but it is not a defense. 2. Advanced intoxication [start with this defense] – depending on the facts, can raise a reasonable doubt about whether the accused formed specific intent (for specific intent offences like murder and assault with intent to resist arrest) Specific intent – intent beyond just the physical assault When someone is quite drunk, then that can raise a reasonable doubt about whether they formed the specific intent to kill for murder or assault for intent to resist arrest A highly intoxicated person will try to use this defense as not foreseeing death from their actions It is a factual question at the end of the day whether this specific person formed the intent Not just how drunk they were, but what did they do? With certain actions might be easier to see if they foresaw death (ex: drunk and shooting point blank another person in the head vs. in a brawl and kicking someone) 3. Extreme intoxication [very rare defense]– makes the accused’s actions involuntary and applies to general intent offences of non-violent nature only (ex: theft, drug trafficking, property damages) by Code, s. 33.1 (which may be unconstitutional under R. v. Daviault) S. 33.1(3) of the Code: This section says Daviault defense removed for violent offences – interference with, or threat of interference with the bodily integrity of another person Extreme intoxication that can result in involuntariness may be unconstitutional if denied for violent offences Crown would still argue s.33.1 – it’s just under a cloud This defense raises doubts around actus rea as well 8. Justifications and Excuses True defenses justify both the actus rea and mens rea – ex: self- defense, duress, necessity and provocation 103 Ratio/importance of case issue case main VS Defenses that negate certain elements of the offence – ex: no actus rea in involuntary acts. No fault element if you lack knowledge that a heap of white powder is cocaine. Sources of true defenses: i. Common law S.8(3) of Code preserves common law defenses, (but not offenses). ii. Statutes 1) Introduction I. R. v. Cinous [2002] – “Air of reality” test for ALL Defenses Test applies to all defenses – including mistaken belief in consent TEST FOR “AIR OF REALITY”: Whether there is evidence on the record upon which a properly instructed jury acting reasonably could acquit. First, consider whether defense even arises A defense should be put to a jury if there is an evidential found for it – only if there is then you explain to the jury the particular defense raised Note: judge does not have to explain all defenses that are not relevant because it may confuse the jury Second, what are the merits of the defense? Where defenses are raised, crown has to disprove it beyond reasonable doubt that no defense. ON EXAM: you wouldn't spend a lot of time talking about air of reality - be aware of it, and if defense looks weak you can mention it might not have air of reality, but main analysis is whether the defense actually exists or not 2) Defense of person Also known as self-defense or if defending another person against an aggressor This defense is understood as a justification which makes the wrongful act right, as opposed to “excusing” the wrongful act. 104 Ratio/importance of case issue case main However, no language in the code about justification for self-defense BUT the defense itself covered in s.34(1): a person is not guilty of an offence if… a) reasonable belief that force is being used against them b) has to be a defensive purpose – not simply that you’re being threatened so you take the opportunity to kill the person because you hate them c) defensive act is reasonable in the circumstances – does it go too far if they weren’t under that much threat? (Use factors listed in s.34(2) to determine if reasonable). Limitations on this defense: for defending/protecting oneself or another person AND act must be reasonable in the circumstance factors for reasonableness under s. 34(2) include (see code for full list): the extent to which the threat was happening further, statute also talks about whether other means were available to defense such as retreat, call the police 34(2)(c) if the person claiming self-defense was the initial aggressor, that weakens the selfdefense claim grounded in claim (ex: if you started the fight but started losing it so took your knife and killed the person). threats made with weapons are much more serious and dangerous. (g) very important – response should be proportionate to the original threat. interpretative issues of self-defense laid out in s.34: the person who is subject to force the notion that you would be required to weigh it to a nicety (ex: 3-inch knife for a 3inch knife and not a gun instead) enot required to weigh to a nicety because law acknowledges the limited options you are operating under – ex: if being threatened with knife but you only have gun. need to take into account the person’s subjective and reasonable understanding (i.e. mistaken self-defense such as thinking the other person has a gun, so you shoot them, but they really don’t have a gun) to justify the person’s action of using force. retreat – under 34(2) whether other means available. no specific requirement that you always retreat. Rather, it is unnecessary if you’re in your own home. so, ability to use selfdefense is likely to be higher in home than in any other place. while they’re centrally aimed at a classic self-defense situation, but in fact the language is so broad that it could involve to other kinds of criminal act that may not involve act – it 105 Ratio/importance of case issue case main may go beyond classical self-defense situations. it gives rise to possibility of swallowing the defense of necessity (such as breaking into a car to get away from assault and using self-defense for theft?) and captures those defenses as well. I. R. v. Lavallee [1990] – self-defense by woman in an abusive relationship - battered woman syndrome Facts: accused was battered woman she killed her partner by shooting him in the back of the head as he left the room he said “wait until everyone leaves and then you’ll get it, either you kill me or I’ll kill you” PROBLEM: he was not about to attack her, maybe she had other reasonable alternatives Up until this case, it was thought to be inherently unreasonable to apprehend threat of death or grievous bodily harm unless physical assault was in progress Issues: Does she have a viable claim of self-defense? Were her fears of being attacked and her response to those fears reasonable in the circumstances? Decision: Lavallee found to have valid self-defense claim Reasoning: (Wilson J/MAJORITY) Wilson notes that difficult what a reasonable man would do because men don’t typically find themselves in situation of threat by their partner – such violence is very gendered and Wilson makes a very important note on this. Imminence threat requirement under traditional common law rule (self-defense only available for imminent threat to make sure self-defense only used when really necessary, not for revenge) - Court sees it as too restrictive in case of battered women problem is that the woman has to wait until there is real danger to her at which point, she may not even be able to defend herself DURING the abusive act. Expert evidence important on battered women syndrome - without this evidence, regular people wouldn't have the information to know if her fears were reasonable in the circumstances battered spouse has heightened appreciation to know when there could be violence, esp. life-threatening based on their history with the abusive partner– what is reasonable in her circumstances with her perceptions/relationship with the spouse Have to look at her perceptions, history and experience to determine whether her use of force was reasonable Not what an outsider would reasonably perceive, but what the accused reasonably perceived she believed she couldn’t preserve herself without using lethal force (battered women syndrome not defense in itself, but helps inform how it applies in the circumstances) 106 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Ratio: the need for expert evidence in analyzing self-defense in battered women syndrome cases, not that battered women can get away with self-defense any time. II. R. v. Malott – “battered women” syndrome not a defense in itself – rather, allows for expert evidence to be used for accused women in abusive relationships Facts: accused and deceased lived as common law spouses, deceased abused the accused she shot him, and went to the deceased’s girlfriend’s home and shot and stabbed her she testified to the extensive abused she had suffered – battered women syndrome Decision: jury at trial found her guilty of second-degree murder and attempted murder of the girlfriend. COA and SCC affirmed the convictions because “no air of reality” to the defense of self-defense. Reasoning: (Obiter by L’Heureux-Dube and McLachlin JJ) battered women syndrome is not a legal defense in itself such that an accused woman need only establish that she is suffering from the syndrome to gain acquittal - the defense is self-defense, but battered women's syndrome is considered in meeting the requirements of that larger defense Lavallee also implicitly accepted that women’s experiences and perspectives may be different from the experiences and perspectives of men Objectiveness test still applies but it’s not the “reasonable man” Look more specifically to level of threat, relationship, physical capabilities, etc. and expert evidence in analyzing self-defense of battered women. Concern that battered women’s syndrome creates a new stereotype – “damsel in distress” picture acknowledge reasons why battered women don’t leave their abusive spouses – finances, protect children All affirm women’s beliefs/response Battered women’s experience is individual but there are some shared features – both important when assessing reasonableness of circumstances III. Cormier v. R. [2017] – acting in defense of property can also result in defense of person Facts: 107 Ratio/importance of case issue case main Cormier charged with 2nd degree murder after killing E. E threatened C on a number of occasions such as through texts to break the windows of his dad’s apartment where C had locked himself up C and his dad and a friend go out with pipes and knives to defend themselves E swung a pipe at C at which point C stabbed E, resulting in his death. The trial judge wrongly instructed the jury that in leaving the house, C forfeited any selfdefense claim so C appealed on that to NB CoA. NB CA: Appeal successful; wasn’t true that opening the door barred C’s self-defense claim accused was technically just defending his dad’s property which they had a right to by going out to prevent the damage or entry by A; if in that context E attacked C, he could have a self-defense claim C would be justified in defense of property so not really a pure self-defense case. Rather, opening the door is just one step because also involved defending property. no duty to retreat from one’s home in this case POLICY ON SELF-DEFENSE This is a body of law that is very important in the current context: When police shoot civilians this is the body of law that often forms the basis of their defence Linked to race issues in both Canada and the States Ie. Sammy Yatim case in Toronto o Holding knife on streetcar and shot 8 times o Forcillo claimed defense, but Yatim was 10 feet away at the time so didn’t look like much of a threat o Also, officer Forcillo shot 6 more times after shooting Yatim thrice and while he was lying on the ground – which is attempted murder. Difficulty of the law in this area o Concern of the law is to make sure that people in situation of self-defense don't have too high of a burden to meet, because they’re in an emergency situation o BUT if we don’t have some strictness, especially in situations with undercurrents of racial inequality, we have issues of people being exposed to very excessive uses of force by police that shouldn’t be justified o Perhaps different legislation to govern police using force because they themselves targets of violence due to uniforms o More training in racial tensions o racial aspect very important many cases of white people seeing racialized people as threats due to the racial bias they’re operating under – it is not reasonable. 3) Defense of property s.35 of the Code lays out this defense but no list of factors for what is reasonableness. 108 Ratio/importance of case issue case main to claim defense of property a person must: reasonably believe they are in “peaceable possession” (i.e. owner) or assisting a person in peaceable possession reasonably believe another person is going to enter, damage, destroy or take the property act for the purpose of preventing the damage, entry, taking, etc. (subjective) act in a way that’s reasonable in the circumstances (objective) usually defending real property – usually one’s home or land – but could also be a valuable piece of property like car or an art piece and the same section s.35 would apply. intentionally killing a person in defense of property – like just of trespassing property – it is inherently disproportional not in the Code but a common law understanding that can be tied in. factual = what justifies as a defence of property could turn into a defense of person (ex: Cormier case) 4) Necessity I. necessity applies in emergency – doesn’t apply just to sea-faring or starvation incidents. on the face of it, it could cover any situation (such as person coming at you with a knife and so you have to shoot). if you have an obvious self-defense defense, then you talk about that and not necessity. selfdefense is a statutory defense whereas necessity is a common law defense. self-defense can swallow up necessity – what the lines are blurry. if on exam: one person using force against another, (force v. force), it would be self-defense – no need to go into necessity afterwards (self-defense would be enough). R. v. Dudley and Stephens (1884) UK: no defense of necessity recognized to kill a life for food Guys on boat stranded; starving; finally decide to kill and eat a boy 109 Ratio/importance of case issue Facts: Issue: Ratio: case main A special verdict case in which jury from lower court asked to give facts and then referenced to a higher court. D & S charged with murder of cabin boy Richard Parker, after they were cast away on a lifeboat and lost at sea They run out of food and on the verge of death after 3 weeks of being lost Richard Parker had fallen sick from drinking sea water, so perhaps he would have died anyway D & S decide the boy should be killed so the rest can survive (third guy Brooks dissent) The boy did not consent to being killed or eaten Dudley committed the act of killing; all three ate the boy 4 days later they are rescued, even though there wasn’t any reasonable expectation of them being rescued If they hadn’t killed and eaten the boy, they probably would have died by the time they were rescued. D & S charged with murder for killing Richard Parker Brooks not charged because he dissented, did not want to kill and definitely did not participate in the act (he did eat the boy, which is a moral issue and a different offence than what’s being discussed here) Is necessity a defense for murder for your own survival, especially when the other person has not provoked aggression? Can murder be justified out of desperation to save one’s own life? Necessity is not a defense to murder (broadly) Taking the life away of a person when they haven’t provoked aggression is not a defense (narrow) Reasons: Notes: Lord Coleridge: Dangerous precedent if acquitted because it would open the floodgates by allowing murder to always be justified in some broad way While not every immoral act is illegal, need to be careful on how much to divorce morality from legality and inappropriate to do so in this case because if we allow defence by accused of “temptation” to murder, then there would be fatal consequences...murder is immoral and that shouldn’t be divorced from the law. Who decides how we value one life more than another? Who decides whose necessity is more important and thus grants them survival than another person [ex: they decided to kill the boy because he was already dying – well, why not kill Brooks?] What if Richard Parker had consented? What if straws had been drawn to decide who dies – maybe this is fairer but what is real consent? D & S guilty of murder but consider context for deciding appropriate sentencing Charged with capitol punishment but Queen Victoria eventually brought down the charges to 6 months in jail Law showing its hard-core approach to maintaining morality of certain acts but at the same time taking context into consideration for sentencing 110 Ratio/importance of case issue II. case main Not in this case, but perhaps in other cases necessity could be a defence? Ex: conjunct twins who share a heart and both are dying unless surgery is performed to move the heart completely to one body, in which case one would have to die. R. v. Perka [1984] – necessity accepted as an excuse, not justification – 3 PART TEST FOR USING THIS DEFENSE FACTS: drug smugglers from Columbia to Alaska – ship in trouble so had to bring it ashore to repair it and unload it to unloaded their cargo of marijuana in BC charged with importing cannabis – put it on the beach of Vancouver Island they said no intention to leave or traffic any marijuana in Canada other ex: throwing people overboard to save others, or speeding to bring someone injured to the hospital REASNONING – Dickson: there is a necessity defense in Canadian law rejects necessity as a justification, saying a “choice of evils” approach is too subjective a choice where what’s the consequence of not letting the boat come on Vancouver Island (and thus letting everyone on board die) vs. allowing cannabis to be unloaded onto the island, albeit illegal in Canada, for the purposes of repairing the boat. weigh the evil of staying out in the sea by not bringing the cannabis against that of bringing the cannabis into Canada Justice Dickson rejects it because: people cannot be allowed to decide on a subjective basis when it’s worthwhile to follow the law in different circumstances instead, accepts necessity as an excuse based on a “realistic assessment of human weakness” where following the law would be intolerable. not realistic for people to sacrifice themselves for the sake of respecting the law – act is still wrongful but not justifiable pressing circumstances people find themselves under would allow us to excuse themselves from obeying the law. accepts this because: situations of “moral involuntariness” – think back to physical voluntariness in epilepsy attack you’re overwhelmingly compelled to do it because no other choice – realistically unavoidable. The Court concludes that “a liberal and humane criminal law cannot hold people to the strict obedience of laws in emergency situations where normal human instincts, whether of selfpreservation or of altruism, overwhelmingly impel disobedience.” 111 Ratio/importance of case issue case main These are situations of “moral involuntariness” because the actor has no real choice but to break the law – the act is “realistically unavoidable” why would be punish someone for what they don’t have a choice about? three-part test by the court: (IMPORTANT TO STATE IT IF ON EXAM) 1. An urgent situation of imminent peril possibility of a rescue ship, storm passing – situation must be critical (so the possibility of rescue has passed as well) 2. no reasonable legal alternative compliance with law must be demonstrably impossible whether something else they could have done other than importing the law 3. proportionality between harm inflicted and harm avoided harm inflicted by breaking the law should be LESS than the harm sought to be avoided by not breaking the law can’t blow up a city in order to prevent your finger from breaking for example there should be some pressure to break the law Notes: even though doing something illegal, necessity still available, unless you get yourself into an emergency that you know will rise from your illegal act NOTE: VERY NARROW DEFENSE – doesn’t cover a lot of situations onus of proof necessity on the CROWN lost alpinist – breaking into the cabin to save himself from the cold vs. squatters claiming necessity for occupying empty houses on necessity of their homelessness (former accepted necessity defense, but not later – why?) necessity has to be acute, short term emergency whereas homeless is a long-standing problem which is a social state of affairs III. R. v. Latimer [2001] – further interpretation of the PERKA 3-PART TEST for NECESSITY: Latimer killed Tracy with carbon monoxide poisoning kills his severely disabled daughter because doctors wanted to do surgery which he thought would be mutilating her further he claims he did it out of necessity convicted both times by jury – second degree murder further interpretation of Perka 3-part test: 1. peril has to be “on the verge of transpiring and virtually certain to occur” 2. no reasonable legal alternative – realistically assess options 3. proportionality between harm inflicted and harm avoided – not required that harm avoided clearly outweigh the harm inflicted – at a minimum the must be of equal gravity. modified objective test for 1 & 2 (NOT SAME UNDER THE OBJECTIVE FAULT OFFENCES) here, it means we do an objective evaluation that takes account of the characteristic and situation of the accused. accused must have honestly believed on reasonable grounds that he or she was in imminent peril with no legal way out. requirement 3, proportionality, is assessed objectively 112 Ratio/importance of case issue case main inflicted death on Tracy which is not proportional to following the law and was disproportionate. no air of reality to any of these requirements on the facts his motivation was not amongst the worst kind – in some worked way, he thought he was doing the right thing for his daughter. shows how harsh the homicide laws are. 5) Duress I. different from necessity – no threat there duress – covers situations where accused commits offence from pressure from someone else ex: bank robber gets into a car, holds the gun to the head to speed and break all red lights section 17: committing an offence under compulsion by threats this is thought of an excused defense section 17 requirements: 1. threat of death or bodily harm to the accused or a third party threat to property or even a dog is not excusable 2. immediacy: act committed under threat of “immediate death or bodily harm” 3. presence: Threatener must be “present when the offence is committed” 4. Belief: accused must “believe…the threats will be carried out” 5. accused not party to conspiracy so if you’re already involved with a gang and told to beat up someone and you don’t do it and are under threat for that, you can’t use defense of duress 6. exclusion of certain offences: statutory defense of duress not available for murder, sexual assault, robbery, etc. however, s17 cannot be read at face value anymore – these requirements have been modified in light of the Charter R. v. Paquette [1977] – s.17 limitations on defense of duress only apply to principle offenders, not aiders/abettors FACTS: 113 Ratio/importance of case issue case main robbery which resulted in an innocent bystander’s death – both the robbers pled guilty to murder the accused, driver, also charged with murder driver claims defense that he did not want to drive them to the robbery but he had a gun held to himself however, problem is that robbery EXCLUDED from s.17 so no defense of duress Ratio: The s17 defense of duress is only applicable to principal offenders Reasoning: SCC could have simply said no defense of duress instead, they said s.17 only applies to the person who actually commits the offence (known as the principle), not to people who HELP that person (aiders and abettors) SCC held that s.17 only applies to the person who actually commits the offence, not other parties: this view is based on s.17, which says “a person who commits an offence under compulsion by…” it doesn’t say a person who is a PARTY to the offence, but rather only talking about the principle good thing for Paquette because: s.17 is codified defense of duress only for the principle offender– since no codified defense for aiders and abettors (i.e. Paquette), then you can look at the common law defense of duress. he’s just a party so only helping with the robbery and murder – he didn’t do it himself therefore, he gets common law defense of duress which SCC accepts good news for him because s.17 has all the exclusions under number 6, not clear whether those offences are excluded in common law so he could have common law defense for murder or robbery as an aider or abettor. NOTES: unwelcomed complexity obviously in law of duress – on the other hand, some justification for having difference between principle and third parties for defense of duress: principle actually shoots the person, person who hands the gun some more sympathy to handing the gun if you have a gun to your head whereas the person who is shooting because more moral blame worthiness not accept duress for actual shooting (i.e. murder) because when is it ever proportional to kill someone else? if you’re going to be killed unless you execute someone else, then just be killed law holds you to a higher moral standard. but isn’t that extreme? need to have a sliding scale of proportionality in defense – to have something in between for some sympathetic cases – what about a principle under duress to kill someone or their child will be shot? 114 Ratio/importance of case issue II. III. IV. case main R. v. Hibbert [1995] – common law duress defense requires “no safe avenue of escape” common law defense of duress of Hibbert, who was an aider and abettor like necessity, duress is an excuse based on moral involuntariness and no realistic choice first additional requirement added to COMMON LAW defense of duress for aiders/abettors: (no safe avenue of escape) just like necessity, it is judged on a modified objective standard – i.e. take into account accused’s personal characteristics. R. v. Ruzic [2001] – reads out immediacy and presence requirement from s.17 defense of duress due to Charter: Ruzic imports narcotics from Serbia to Canada – under threat from a criminal gangster in Serbia – if not, he would kill the mom in Serbia she is the principle, not aider and abettor, so s.17 does apply to her. Also, drug trafficking not on the the list of offenses excluded so she can use that defense. problem is that person threatening her wasn’t right beside her (he was in Serbia) so not an immediate threat SCC says: her act was morally involuntary – she had no realistic choice because SCC argues that she did not have a safe avenue of escape because at the time in Siberia, there was no law enforcement – police to whom she could have gone to due to political instability. under s.7 of the Charter, there is a principle of fundamental justice that only morally voluntary conduct can attract criminal liability. s.17 violates s.7 of the Charter because immediacy and presence requirements remove the defense for some morally involuntary acts s.17 excludes certain acts that are morally involuntary, which goes against s.7 the immediacy and presence requirement were read of out s.17 and the following remains: 1. threat of death or bodily harm to the accused or a third party (so not to you, but a second party in the car) 2. immediacy: act committed under threat of “immediate death or bodily harm” 3. presence: Threatener must be “present when the offence is committed” 4. Belief: accused must “believe…the threats will be carried out” 5. accused not party to conspiracy so if you’re already involved from the 6. exclusion of certain offences: statutory defense of duress not available for murder, sexual assault, robbery, etc. R. v. Ryan – 7 requirements for statutory defense of duress vs 6 requirements for common law duress defense: 115 Ratio/importance of case issue 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. case main Nicole Ryan physically abused by her husband – threatened her and their daughter’s life went to police on several occasions but they did not protect her (kind of like Ruzic in Siberia) she decided to have him killed unlike Lavalé who shot her partner herself, she decided to hire a hitman over several months the police found out because of her several attempts to hire one charged with counselling murder – if you ask or advice or hire someone to murder based on defense of duress – problematic because seems more like self-defense – experiencing aggression and thus responds through force by hiring a hitman) self-defense was not broad enough to cover this so Ryan should be allowed to cover duress defense of duress only available when the accused “commits an offence under compulsion of a threat made for the purposes of compelling” the accused to commit the offence – whatever her husband did to her in terms of physical abuse, he did not COMPEL his wife to kill him (why would he do that?) so, court said duress not available statutory defense of duress by court: threat of death or bodily harm to the accused or a third party (so not to you, but a second party in the car) threat to property or even a dog is not excusable Belief: accused must “believe…the threats will be carried out” accused not party to conspiracy so if you’re already involved with a criminal organization you can’t claim defense of duress exclusion of certain offences: statutory defense of duress not available for murder, sexual assault, robbery, etc. Plus three common law requirements from Hibbert which also apply to statutory defenses which ensure moral involuntariness: no safe avenue of escape – on a “modified objective standard” (characteristic and situation of the accused) (Hibbert) close temporal connection between threat and harm (ex: Ruzic) proportionality – harm threatened at least equal to harm inflicted by accused (similar to proportionality requirement in necessity), and accused must show normal resistance to the threat (like in necessity) – also on “modified objective standard” Common Law Defense of duress (under R. v. Ryan) – 6 requirements: 1. threat of death or bodily harm to the accused or a third party (so not to you, but a second party in the car) 2. Belief: accused must “believe…the threats will be carried out” 3. accused not party to conspiracy so if you’re already involved with a criminal organization you can’t claim defense of duress 4. exclusion of certain offences: statutory defense of duress not available for murder, sexual assault, robbery, etc. whole purpose in Paquette!! Plus three common law requirements from Hibbert which also apply to statutory defenses which ensure moral involuntariness: 116 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 5. no safe avenue of escape – on a “modified objective standard” (characteristic and situation of the accused) (Hibbert) 6. close temporal connection between threat and harm (ex: Ruzic) 7. proportionality – harm threatened at least equal to harm inflicted by accused (similar to proportionality requirement in necessity), and accused must show normal resistance to the threat (like in necessity) – also on “modified objective standard” SUMMARY OF DURESS only two differences remain between statutory and common law duress defenses: 1. the statutory defense applies only to principals, while the common law defense applies to other parties 2. the statutory defense excludes a number of offences, and it’s unclear whether any offences are excluded from the common law defense principle of fundamental justice in Ruzic – by excluding principles in a robbery case where they might have been acting involuntary conduct from defense of duress would be contrary to s.7 (think back to a mother acting under duress to kill a person or her child dies) the statutory exclusions may also be unconstitutional if they remove the defense in situations of moral involuntariness recall Ruzic holds that under s.7 of the Charter, there is a principle of fundamental justice that only morally voluntary conduct can attract criminal liability. moral involuntariness never met when a person intentionally actually kills a person because proportionality never met so principle needs to be held to a high standard of morality. Ex: woman under duress from her husband to assault her child. She is principal so statutory defense of duress would apply. However, assault is excluded under the 6th requirement so now what? Can there a similar Charter argument like Ruzic? 6) Provocation 117 Ratio/importance of case issue I. case main Can claim both self-defense AND provocation!! Partial defense to murder is a defense that does not lead to the person being acquitted, but instead of being convicted of murder, they are convicted of manslaughter. One example of partial defense is extreme intoxication. Provocation is another example Where provocation defense is successful, the person is convicted of manslaughter instead of murder. IT ONLY APPLIES TO MURDER – NOT TO ANY OTHER OFFENCE!! It is a statutory defense that ONLY APPLIES TO MURDER. And only convicted of manslaughter where they killed someone in a heat of passion. s.232 of the Code: MURDER REDUCED TO MANSLAUGHTER 232(1) & 231(2). Subsection 2 of s.231 has been amended – it used to be provocation used to be a wrongful act. New language says: victim must have done something that would constitute an indictable offence, 5 years max (so assault or sexual assault would count) and it would deprive an ordinary person power of self-control Racial slur is offensive and insulting but not a provoking act today. R. v. Tran – ELEMENTS OF PROVOCATION DEFENSE IGNORE FACTS Comes from prior state of law before provocation and talks a lot about insult which is not in statutory language anymore so bad law kind of like that But still some good stuff Adultery cases where a man broke into home of his estranged wife and found her with new bf Kills the bf Trial judge accepts the defense and convicts of manslaughter. Appeal: No air of reality to the defense of provocation and therefor Tran should be convicted of murder Two elements in this defense: 1. Objective element: there was provoking conduct (which now must be an offense) sufficient to deprive an ordinary person of self-control When looking at ordinary person, have to infuse them with contemporary norms including fundamental values of the Charter Adultery not an offence in and of itself so it won’t count as raising provocation defense (making it narrower) 2. Subjective element: the accused was actually provoked, lost control and acted while out of control Suddenness is a requirement – in the sense that it strikes a mind unprepared for it Tran trouble in both issues because he knew about the cheating wife before hand Also, not sudden because he followed the bf room to room trying to attack him. Thus, no air of reality of this defense because: 118 Ratio/importance of case issue case main 1. No insult 2. No suddenness about alleged insult or homicidal response. II. R. v. Hill – who is the ordinary person who is provoked: Accused Hill – 16 years old boy Stabbed to death a man who was his Big Brother Hill said that the victim was provoked by the victim’s sexual advances. Jury convicted him of 2nd degree murder Jury should have been told that the ordinary person would have deprived of self-control – but the ordinary person should be of the same age as Hill Who is the ordinary person? Maybe it should reflect some of the characteristics of the accused If you can’t take a person’s characteristics into account, how can you understand racial slur being insulting enough to lead to provocation? But isn’t the purpose of criminal law to have standard behavior rather than shifting standards based on individual characteristics? Dickson: First, clearly the ordinary person is a person of normal temperament and self-control Person can’t be exceptionally excitable – none of these things taken into account for ordinary person Btu still need to consider characteristics that are relevant to considering ordinary person in some circumstances – gives example of racial slur where you will need to take the race into account to understand ordinary person Held: Ordinary person does not possess personal characteristics but only to the extent they are relevant to the provocation (ex: age, race etc.) Notes: 3 types of cases that raise this defense: homo-phobic sexual homicide (like Hill), adultery cases, excessive self-defense cases these cases are the least problematic in terms of discriminatory tones unlike the first two. How to answer Fact Pattern: o o o Actus Reus Mens Rea - make some reference to fault, even if not really contentious Defences - only mention if it is actually an issue Policy Qs ask you to explain the law and then comment on it - MAKE SURE YOU DO ACTUALLY COMMENT ON THE LAW ITSELF, and then strength/weakness, too vague, not protective enough of victims 119