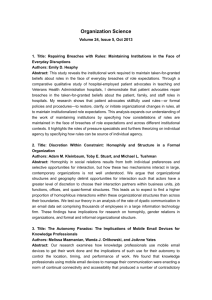

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242076259 Understanding Customer Engagement in Services Article · January 2006 CITATIONS READS 73 4,275 2 authors, including: Paul G. Patterson UNSW Sydney 117 PUBLICATIONS 6,223 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Customer anger and rage View project The impact of interpersonal communications on client loyalty in professional services View project All content following this page was uploaded by Paul G. Patterson on 07 July 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. European Journal of Marketing Converting service encounters into cross-selling opportunities: Does faith in supervisor ability help or hinder service-sales ambidexterity? Ting Yu Paul Patterson Ko de Ruyter Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Article information: To cite this document: Ting Yu Paul Patterson Ko de Ruyter , (2015),"Converting service encounters into cross-selling opportunities", European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 49 Iss 3/4 pp. 491 - 511 Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EJM-10-2013-0549 Downloaded on: 04 May 2015, At: 00:52 (PT) References: this document contains references to 62 other documents. To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 61 times since 2015* Users who downloaded this article also downloaded: Pilar Carbonell, Ana Isabel Rodriguez Escudero, (2015),"The negative effect of team’s prior experience and technological turbulence on new service development projects with customer involvement", European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 49 Iss 3/4 pp. 278-301 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ EJM-08-2013-0438 Luiza Cristina Alencar Rodrigues, Filipe Coelho, Carlos M. P. Sousa, (2015),"Control mechanisms and goal orientations: evidence from frontline service employees", European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 49 Iss 3/4 pp. 350-371 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EJM-01-2014-0008 Valentyna Melnyk, Tammo Bijmolt, (2015),"The effects of introducing and terminating loyalty programs", European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 49 Iss 3/4 pp. 398-419 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ EJM-12-2012-0694 Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by 486125 [] For Authors If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) *Related content and download information correct at time of download. The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/0309-0566.htm Converting service encounters into cross-selling opportunities Does faith in supervisor ability help or hinder service-sales ambidexterity? Service-sales ambidexterity 491 Ting Yu and Paul Patterson University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, and Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Ko de Ruyter Received 8 October 2013 Revised 27 March 2014 28 July 2014 Accepted 14 August 2014 University of Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands Abstract Purpose – This paper aims to examine how the motivation and ability of individual employees to sell influences their units’ capability to align their service delivery with sales in a way that satisfies customers. It also addresses the potential influence of employees’ confidence in their supervisor’s ability to sell, such that they predict a joint influence of personal and proxy agency. Design/methodology/approach – This study uses hierarchical linear modeling to address the research issues. Findings – Employees’ learning orientation has a positive influence on service-sales ambidexterity, but the impact of a performance-avoidance goal orientation is negative, and a performance-prove orientation has no influence. Proxy efficacy enhances the positive impact of learning orientations due to the manager’s ability to lead by example, facilitate knowledge sharing and provide advice. However, it attenuates the impact of self-efficacy on service-sales ambidexterity, because skilled supervisors tend to take over and eliminate opportunities for employees to build their own skills. It also confirms the positive influence of service-sales ambidexterity on branch performance. Originality/value – To examine the emerging service-sales ambidexterity issues raised in frontline service units, this study adopts a motivation and capability paradigm. It is among the first studies to address service-sales ambidexterity issues by considering both individual and branch contextual factors. Keywords Cross-selling, Self-efficacy, Goal orientation, Proxy efficacy, service-sales ambidexterity Paper type Research paper Introduction Service firms increasingly find that their revenues depend on selling more products to existing customers. Wells Fargo claims that its household cross-selling ratio of 5.70 financial products is responsible for more than 80 per cent of its revenues, such that the bank has incorporated cross-selling as a strategic priority for all its retail branches (Wells Fargo, 2011). A McKinsey & Co. report suggests that firms can add 10 per cent to their existing revenues by integrating cross and upselling functions into traditional service centers (Eichfeld et al., 2006). This estimate is based on the premise that in their encounters with customers, frontline employees (FLEs) develop an in-depth The authors gratefully acknowledge that funding for this study was provided by the Australian Research Council (DP110103527). European Journal of Marketing Vol. 49 No. 3/4, 2015 pp. 491-511 © Emerald Group Publishing Limited 0309-0566 DOI 10.1108/EJM-10-2013-0549 EJM 49,3/4 Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) 492 understanding of their needs, such that these employees are particularly well suited to identifying sales opportunities, even as they continue to service customers (Sparacino, 2005). However, Mittal et al. (2005) caution that transforming traditional service units into service- and revenue-generating units can result in unexpected, disappointing consequences, such as deterioration in both service and sales levels (Aksin and Harker, 1999) and/or employee dissatisfaction (Dart, 2009). Many employees seek direction and guidance from operational managers, with their greater status, experience and direct reward power (Yaffe and Kark, 2011). The extent to which service employees depend on these leaders for guidance regarding ways to start selling should influence the impact of their own motivation and self-confidence on their service-sales ambidexterity. However, extant research has been virtually silent on the influence of operational managers, in terms of either their leadership by example or their ability to provide a social context that influences FLEs’ willingness and ability to engage in ambidextrous behavior. We turn to emerging research that uses the concept of ambidexterity as a theoretical perspective for examining service-sales conversion. Ambidexterity, or an organizational entity’s ability to perform seemingly conflicting tasks and pursue disparate goals simultaneously, provides a compelling conceptual lens on the potential competitive advantages to be achieved from combining existing competencies (i.e. service delivery) with new alternative activities (i.e. cross-selling). Most studies focus instead on contextual mechanisms, such as (support) systems, controls or incentive schemes, leaving a gap in our understanding of how the motivation and ability of individual FLEs might predict ambidexterity, beyond pertinent contextual mechanisms. For FLEs, the challenges of providing service and cross-selling simultaneously have long been acknowledged (Burton, 1991); however, they have not been properly addressed. Employees often view selling as incommensurate with service, which creates psychological barriers to blending the two functions (Jasmand et al., 2012). Many service firms report disappointing returns, employee disgruntlement and adverse effects for customers in response to introducing sales initiatives (Aksin et al., 2007). Service firms thus need a more in-depth understanding of how the motivation and ability of individual employees to sell influences frontline service units’ capability to align service delivery with selling, to the satisfaction of customers. This article offers two contributions in this realm. First, we assess how FLEs look up to operational managers or team leaders for guidance or help with integrating sales into the service delivery process. In complex goal pursuits, people tend to seek guidance or even allow others to take over some decision control, according to their own perceived ability. We consider proxy efficacy or a person’s confidence in the knowledge and abilities of a third party to achieve desired outcomes on his or her behalf (Bray et al., 2001). With this study, we examine whether proxy efficacy reinforces or interferes with the influence of individual employees’ selling goal orientations and self-efficacy as predictors of service-sales ambidexterity. Second, on the basis of social cognition theory, we identify for the first time employee goal orientation and self-efficacy as important predictors of successful service-sales ambidexterity. We theorize and empirically assess the predictive ability of these individual-level predictors, compared with the formative influence of two contextual mechanisms, performance management and social support – already identified as important drivers of ambidexterity (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004). Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Conceptual background service-sales ambidexterity Conceptually, organizational ambidexterity is anchored in the distinction between exploration and exploitation (Simsek et al., 2009). Most studies of organizational ambidexterity refer to technological innovation or organizational learning contexts (Gupta et al., 2006), although some recent introductions of service-sales ambidexterity concepts include the simultaneous pursuit of service and sales objectives by service firms (Jasmand et al., 2012). The fundamental premise is that service delivery and selling are two non-substitutable, interdependent activities. Although selling is commonly regarded as a revenue-producing activity, and service delivery generally represents an expenditure, service and sales also can be viewed as interdependent activities, because the sale of an appropriate item provides a satisfying solution to a customer problem, and the delivery of service excellence spurs sales (Zeithaml, 2000). A customer who experiences problems managing a variety of insurance policies might be served well by an offering of an all-inclusive, hassle-free package from one financial services provider for example. Because FLEs can simultaneously engage in or switch between service delivery and selling during the same encounter, ambidexterity is commonly viewed as a multiplicative concept; the activities are non-substitutable and interdependent. Such a multiplicative approach also can serve to index performance measures (Cao et al., 2009). Operationally, service delivery and selling compete for scarce resources, making trade-offs unavoidable in the simultaneous pursuit of both goals. For example, successful explorations of cross-selling opportunities could increase average handling times and require operational managers to relax their thresholds for this service parameter. Customer service activities also traditionally appear passive and reactive, centered on well-defined service requests, ready information access, repetition and standardized processes, with an emphasis on implementation and execution – not unlike order taking. In contrast with this focus on being reliable, courteous and efficient, both up- and cross-selling require FLEs to possess greater product knowledge, be proactive and engage in non-routine tasks to identify sales opportunities. For this task, FLEs must take risks, have an ability to identify opportunities and close sales, be flexible and face uncertain returns for their efforts. The uncertainty and variability associated with upand cross-selling thus are incompatible with the efficiency and reliability emphasis of a customer service role, such that the latter could crowd out the time and effort available for selling (Jasmand et al., 2012). Success in an ambidextrous service-sales role requires FLEs to deal with conflicting demands, which create role ambiguity and role conflict, as well as challenges in the process of pursuing multiple goals. Successfully meeting dual roles in turn requires motivation, self-confidence and self-belief. Personal agency and proxy agency For frontline business units to attain service-sales ambidexterity, employees must exhibit a range of appropriate, self-regulating behaviors. Recent theoretical advances in social cognition offer a general consensus that the effective achievement of desirable outcomes depends on personal agency (Sackett et al., 1998). Personal agency stems from both motivation and perceived ability, in that people must be both willing and able to engage in behavioral change (Bandura, 1997). In a service business unit, employees can choose whether to focus on the sales tasks, how much effort to invest in completing the assigned sales task and whether to be persistent and continue investing until the task is Service-sales ambidexterity 493 EJM 49,3/4 Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) 494 completed. Decisional input related to these options depends largely on the goal orientation of individual employees. As a motivational construct, goal orientation indicates individual willingness to invest effort in particular tasks (Covington, 2000). The notion of self-efficacy instead reflects a person’s ability to cope with work-related tasks (Crant, 2000). Ample evidence suggests that perceived confidence in one’s own ability to perform a specific task is a better predictor of behavioral displays than are actual skills (Bandura, 1997). Self-efficacy beliefs are thus crucial to determining whether and how people persist in attempting to achieve certain behaviors, particularly in the face of unfamiliar task challenges (Bandura et al., 1996). We posit that employee goal orientation and self-efficacy related to selling offer important predictors of a boundary-spanning work unit’s capability to be ambidextrous. Social cognition theory also states that people’s adaptation to change is rooted in the social environment and that vicarious experience has an important role (Bandura, 1997): It accounts for proxy agency, in addition to personal agency and motivation, particularly in relation to necessary adaptations to and the internalization of new activities. In adapting to task demands, people rely on their perceptions of the ability of third parties who have authority, act as role models, and offer guidance. In this study, proxy efficacy implies FLEs’ confidence in their manager’s ability to sell in a service delivery context (i.e. “show them how it is done”). As previous research has demonstrated, when people do not have direct control over changes and institutional requirements, they relinquish personal control to a third party to act on their behalf. In a fitness class, participants count on a trainer to guide them through the exercise program; FLEs similarly look to managers to lead the class, by guiding and supplementing their own ability and strengthening their motivation to sell, even in a service delivery context. Thus, they do not have to worry about choosing the right steps or procedure to follow; they also gain more resources, in terms of their time and effort, to exercise service-sales activities because they learn more and get a feel for the impact of specific actions on goal attainment (Bandura, 1997). Therefore, we regard proxy efficacy as a stimulus that strengthens the impact of personal agency on service-sales ambidexterity. Finally, previous research shows unequivocally that properties of the social context (contextual mechanisms) are important predictors of ambidexterity (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004). Therefore, we examine the intricate interplay of an individual FLE’s goal orientation, self-efficacy and proxy efficacy as predictors of service-sales ambidexterity, using several theory-based research hypotheses. Hypotheses development Goal orientation consists of three dimensions: learning orientation, performance-avoid orientation and performance-prove orientation (Vandewalle, 1997). People with a high learning orientation seek challenging tasks and persist in dealing with challenging situations. These employees possess the “desire to develop the self by acquiring new skills, mastering new situations and improving one’s competence” (Vandewalle, 1997, p. 1000). They are motivated to acquire necessary new skills and knowledge and less concerned about failure or mistakes. Instead, they tend to treat mistakes as useful feedback for their improvement or perceive them as growth opportunities (Sosik et al., 2004). The dual demands of service and newly added sales targets offer a challenge to these employees, who must perform an extended, unfamiliar range of activities in Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) encounters with customers, which creates a higher likelihood of failure. When FLEs are motivated by learning though, they are more likely to expend the effort to acquire new selling knowledge and skills, and then align them with existing service quality objectives. The adoption of mastery goals prompts greater intrinsic motivation, so highly learning-oriented employees should tend to persist and better manage the dual demands of service and sales (Sujan et al., 1994). Accordingly, we hypothesize: Service-sales ambidexterity H1a. A learning goal orientation has a positive impact on service-sales ambidexterity. 495 A high performance-prove orientation instead leads people to focus on demonstrating their ability so that they look better than others. They seek approval from their peers and supervisors (Brett and Vandewalle, 1999) by achieving a high level of performance. However, these employees need positive reinforcement and feedback. They may regard challenging tasks as threats to their positive image, yet their desire to demonstrate their competency leads them to focus on doing what they are good at, such that they should align service delivery activities with cross-selling effectively. Even if these employees feel uncomfortable in engaging in attempts to sell, they likely seek to prove their ability to meet the new targets. Thus, we hypothesize: H1b. A performance-prove goal orientation has a positive impact on service-sales ambidexterity. In contrast, a performance-avoid orientation causes people to regard challenging tasks as a threat, likely to result in failure (Brett and Vandewalle, 1999). In the face of a challenging situation, performance-avoid-oriented people pursue maladaptive responses because they would rather withdraw from activities than run the risk of failure (Button et al., 1996). Because they need to invest extra effort to succeed, they believe they have received a signal of their low ability, which discourages further effort investments to achieve the required demands. Previous research affirms that a performance-avoid orientation is detrimental to the exhibition of desirable or required behaviors (Vandewalle et al., 1999) but positively associated with a fear of negative evaluations by others (Brett and Vandewalle, 1999). The dual demand of combining service with sales is unfamiliar for most FLEs, so employees with a high performance-avoid goal orientation are unlikely to display behaviors to meet it. Therefore, we hypothesize: H1c. A performance-avoid goal orientation has a negative impact on service-sales ambidexterity. A firm’s ambidextrous performance relies on employees’ abilities to manage disparate tasks and integrate them for cross-fertilization. Self-efficacy thus has emerged as a key construct for explaining and predicting variations in employees’ job performance. It relates positively to proactive behaviors (e.g. identifying opportunities to improve, proactive problem solving and implementation; Crant, 2000). To act ambidextrously, perform dual roles of service and sales and integrate them well, staff usually must take some proactive actions. For example, in a customer interaction, the FLEs need to take the initiative to identify a problem and find a solution, even if not requested by the customer. The solution might be a new product or an upgrade to an existing product; staff members with higher self-efficacy should be more likely to enact such EJM 49,3/4 Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) 496 task-appropriate strategies (Marrone et al., 2007). In addition, self-efficacy relates to employees’ adaptability during service encounters (Ahearne et al., 2005). Higher self-efficacy increases the chances that a person initiates tasks, sustains effort toward task accomplishment and persists in the face of difficulties or failure (Mittal et al., 2005). Therefore, FLEs who are more confident in their ability to sell should be better at achieving both service and sales objectives during service encounters. We hypothesize: H2. Self-efficacy has a positive impact on service-sales ambidexterity. The notion of proxy efficacy has remained virtually unexplored empirically: Bandura’s (1997) theory has not been tested extensively, and the results that exist are equivocal and limited to health care and academic contexts. Thus, we seek to develop theory-based hypotheses regarding the potential moderating role of proxy efficacy. Bray et al. (2001) conclude that proxy efficacy is not a major determinant of self-efficacy beliefs, and Elias and MacDonald (2007) find that it is not a direct driver of behavior. Yet Bray et al. (2004) report that a combination of self- and proxy efficacy accounts for substantial variance in exercise behavior among novice exercisers. Thus, the influence of proxy efficacy may be supplementary (Bray et al., 2001), in line with Bandura’s (1997) contention that proxy efficacy is influential in contexts in which people transfer partial control to an intermediary who can facilitate their attainment of desired objectives. When confronted with an unfamiliar, challenging task, some people respond by actively seeking to learn new knowledge and skills, to be able to manage the task. Bandura (1997) contends that confidence in the ability of third-party agents (e.g. an experienced, skillful operational manager) can facilitate this learning and skill acquisition process, such that it enhances FLEs’ motivation to master selling activities that promote goal attainment. The transfer of partial control to an agent is common in social settings that demand behavioral changes or introduce new routines. In a medical context, for example, Christensen et al. (1996) note that people who experience health problems are likely motivated to engage in rehabilitation programs, but the assistance of an exercise consultant can be instrumental for sustaining this motivation. They find a positive association between renal dialysis patients’ adherence to their healthcare providers’ recommendations and the amount of confidence those patients have in their healthcare providers’ abilities (Christensen et al., 1996). Similarly, FLEs who seek to demonstrate their abilities to coworkers (i.e. performance-prove orientation) likely achieve better ambidextrous performance when they perceive their operational manager as competent, such that they adhere to this manager’s advice and mimic his or her selling behavior. If FLEs possess a performance-avoid orientation, they also should demonstrate improved performance if their operational manager appears to possess the requisite knowledge and skills to help them achieve their sales targets. Overall, if people lack the experience and skills necessary to engage in required but challenging actions, confidence in a knowledgeable agent who models appropriate behaviors should strengthen the impact of their motivation. That is, motivated staff already are willing to pursue service-sales ambidextrous behavior, and their collectively held confidence in the selling abilities of their manager should reinforce this positive impact on the unit’s ambidextrous service-sales behavior. Therefore, we propose an interaction hypothesis: H3. Proxy efficacy strengthens the relationships of (a) learning orientation, (b) performance-prove orientation and (c) performance-avoid orientation with service-sales ambidexterity. Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Bandura (1997) suggests that the interaction of motivation and confidence in a proxy agent contribute to behavioral adaptations and promote individual performance, but he also notes a dilemma. Using a proxy increases levels of dependence, which ultimately could “impede the cultivation of personal competencies” (Bandura, 2001, p. 13) and reduce “opportunities to build skills needed for efficacious action” (Bandura, 1997, p. 17). Dependence on a proxy agent also might increase the person’s likelihood of constantly depending on others, which Bandura (2001, p. 13) refers to as “the price of proxy agency”. When faced with a new challenge, proxy efficacy thus may mitigate the impact of independent, self-regulatory developments on goal attainment and performance – particularly when achieving the new, unfamiliar objectives demands collaborative effort and proxy instruction. In this sense, “people foster self-induced dependencies when they can obtain valued outcomes more easily by having somebody else do things for them” (Bandura, 1997, p. 17). For example, the mere effort to master a new skill set might seem to outweigh its potential benefits. Accordingly, we posit that proxy efficacy has a negative impact on the self-efficacy–ambidexterity performance relationship. That is, FLEs’ confidence in the ability of their operational manager to sell during service delivery attenuates the impact of their own confidence about infusing sales into service encounters. Admittedly, some congruence must exist between proxy efficacy and dependency because of the formal, hierarchical relationship between the FLEs and their branch managers. Yet such relationships do not apply in settings involving personal trainers or medical therapists for example, though these contexts also have been objects of investigation in proxy efficacy research. Therefore, we anticipate that at high levels of proxy efficacy, the impact the self-efficacy on service-sales ambidexterity diminishes. In relation to the facilitating role of local managers in furthering their subordinates’ motivational and efficacy beliefs, we propose: H4. Proxy efficacy weakens the relationship between self-efficacy and service-sales ambidexterity. In an influential study, Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004) posit that at the work unit level, firms’ operational managers must be able to stimulate the pursuit of exploration and exploitation simultaneously. Contextually ambidextrous organizational units need to combine contradictory organizational elements and support individual employees in their exploration and exploitation activities. Furthermore, a business unit’s capacity for ambidexterity depends on the multiplicative effect of performance management and social support. Ambidextrous organizations delegate responsibility to the work unit level, where systemic, formal and informal processes combine to create an environment that is conducive to the attainment of dual foci. The inherent, seemingly contradictory tensions of ambidexterity thus can be managed through the work context. Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004) also report that ambidexterity relates significantly to a unit’s performance. Although our main research focus is disentangling the effects of individual motivation and ability on achieving service-sales ambidexterity, we also assess the impact of these individual factors, in light of the established influence of contextual mechanisms. Therefore, we incorporate a corroborating hypothesis: H5. The joint impact of performance management and social support is positive for service-sales ambidexterity at the work unit level. Service-sales ambidexterity 497 EJM 49,3/4 Finally, we predict a positive relationship between branch-level service-sales ambidexterity and performance. The dual focus inherent in this type of ambidexterity should be reflected in organizational performance indicators too. We conceptualize performance as the combination of sales and satisfaction performance parameters achieved by the branch: H6. service-sales ambidexterity has a positive impact on performance at the work unit level. 498 An overview of our hypotheses appears in Figure 1. Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Methodology A large nationwide retail bank cooperated for this study, facilitating data collection among staff in the branch network and providing a branch performance index, which included customer satisfaction ratings and financial performance. This study focused on retail banking operations, comprising mainly lending (e.g. personal loans and home loans), deposit-taking, credit cards and savings accounts. All retail branches in operation for longer than six months were invited to participate. We distributed questionnaires to all staff in each of the 350 participating branches and received 2,618 usable questionnaires from 302 bank branches. To ensure a sufficient number of employee respondents in each branch (Lüdtke et al., 2008), we compared the staff size and response rate from each branch. If less than 50 per cent of the staff within a branch responded, we excluded it from further analysis. We obtained a final sample of 2,306 employees representing 267 branches. Data collection and measures The measurement scales for all constructs came from prior literature and should offer content validity (Netemeyer et al., 2003). The Appendix presents a complete list of items with their factor loadings, reliability and average variance extracted (AVE) statistics. Branch Context • • Performance Management Social Support H5 Employee Characteristics Goal Orientation • • • Learning Orientation Performance-Prove Orientation Performance-Avoid Orientation H1a-c Service–Sales Ambidexterity H2 Self-Efficacy Figure 1. Conceptual model H3a-c H4 Proxy Efficacy H6 • • Branch Performance Customer Satisfaction Financial Performance Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) All constructs were measured on seven-point Likert scales. Goal orientation was captured by Vandewalle’s (1997) 13-item goal orientation scale, which consists of three dimensions: learning orientation, performance-prove orientation and performanceavoid orientation. For self-efficacy, we used Sujan et al.’s (1994) self-efficacy scale but modified it slightly to focus on both service- and sales-related skills. The proxy efficacy measure used four items that captured the staff’s beliefs about the efficacy of their branch manager, in terms of his or her ability to sell, which we based on existing proxy efficacy scales (Bray et al., 2004; Elias and MacDonald, 2007). The branch context measures included 12 items (6 for performance management, 6 for social support). As recommended by Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004), we considered both performance management and social support holistically and as non-substitutable; we used a multiplicative function of the performance management and social support constructs to measure the branch context, according to an interaction term. Although prior studies have developed instruments to measure ambidexterity, mostly using self-reported, survey data, little effort has been devoted to developing a reliable, valid scale that applies to service and sales at a branch level. For our measure of service-sales ambidexterity, we therefore adapted items developed by Lubatkin et al. (2006), who argue that their orientation measure reflects an organization’s ability to pursue exploration and exploitation goals. All the items loaded significantly on their respective factors (i.e. service orientation and sales orientation (loadings greater than 0.50), with sound reliability (service ␣ ⫽ 0.89; sales ␣ ⫽ 0.91). We computed the multiplicative interaction between the service and sales components to determine a service-sales ambidexterity level for each branch, as commonly used in previous studies (He and Wong, 2004). Two key indicators measure branch performance: financial performance and customer satisfaction. Data for both indicators came from the participating bank for the most recent financial year. Financial performance was a composite of financial (sales) measures, including volume of deposits, credit card activity, housing mortgage activity and personal loan activity. We measured branch financial performance as a percentage of its overall target, which standardizes this assessment for differences in branch size and market potential. Because this approach also assessed what the branch was trying to maximize, it offered operational validity (Gelade and Young, 2005). Customer satisfaction equaled the average of the customer satisfaction rating reported by customers. A product term combined financial performance and customer ratings. By using an objective rather than a subjective measure, we overcame the problem of self-reported performance bias. We also identified other factors that might influence both service-sales ambidexterity and performance for a given branch. Accordingly, we controlled for employees’ age, gender, tenure and experience, as well as branch size and location (city, suburban and regional). Including these control variables provides a more robust test of the hypotheses. Furthermore, we note that FLEs empowered to deal with the tension of providing services and cross-selling likely suffer from increased workload perceptions, which could have negative impacts on their service performance (Chan and Lam, 2011). Although it thus would be helpful to include workload as another control variable, our data do not provide a valid workload indicator (e.g. number of employees per customer, number of calls per employee per day). Service-sales ambidexterity 499 EJM 49,3/4 Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) 500 Results Table I presents the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all the variables in the study. We established convergent and discriminant validity through exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) (Diessner et al., 2008). We examined the values for the goodness-of-fit index (0.93), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (0.91), root mean square error of approximation (0.05), standardized root mean square residual (0.06), normed fit index (0.94) and comparative fit index (0.95) (Byrne, 2001; Marsh et al., 2004). We also examined within-method convergent validity by checking the significance and magnitude of the item loadings. The Appendix provides the results of the CFA and reliability tests. All coefficient alpha values were greater than 0.78, suggesting acceptable reliability (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). As for within-method convergent validity, all items loaded significantly on their respective constructs (minimum t-value ⫽ 23.78) and had standardized loadings of at least 0.50. To establish discriminant validity, we followed Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) recommended procedure. As the Appendix shows, the AVE for all constructs were greater than 0.50 (range: 0.53 to 0.78). We compared each construct’s AVE with the square of the correlation between any two constructs, and the AVE exceeded the square in all cases. In addition, chi-square difference tests (1 degree of freedom) indicated that all pairs of constructs correlated at less than 1 (p ⬍ 0.05). Aggregation statistics For our study, the measurement level (employee) for branch context and proxy efficacy differed from the analysis level (branch). To justify the data aggregation for these constructs empirically, we performed several tests to demonstrate within-group agreement and between-branch differences (Dixon and Cunningham, 2006). We used one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) to calculate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC [1] and ICC [2]) for the branch context (i.e. performance management and social support) and proxy efficacy (Bliese, 2000). The ICC (1) for branch context and proxy efficacy were greater than 0 (performance management ⫽ 0.29; social support ⫽ 0.30; and proxy efficacy ⫽ 0.37) with a correspondingly significant ANOVA test statistic (F). This value also exceeded the median ICC (1) value of 0.12 in organizational research (James, 1982). The ICC (2) for branch context and proxy efficacy (performance management ⫽ 0.68; social support ⫽ 0.68; and proxy efficacy ⫽ 0.78) were above the acceptable cutoff value of 0.6 (Glick, 1985). According to an interrater reliability coefficient (Rwg) test (James et al., 1993), the Rwg(j) coefficient for the branch context and proxy efficacy were far above the acceptable level (performance management ⫽ 0.96; social support ⫽ 0.97; and proxy efficacy ⫽ 0.97). These results showed high consistency ratings among employees within branches (James, 1982), which led us to conclude that the aggregation of branch context and proxy efficacy to the branch level was appropriate. We took several measures to mitigate any bias. Following Podsakoff et al.’s (2003) suggestions, we separated measures of the independent variables from service-sales ambidexterity by inserting them into separate sections of the instrument. We also assured respondents of their anonymity, thereby reducing any evaluation apprehension or demands for social desirability. Next, because the data came from three distinct sources (customers, objective firm financial performance data and employees), we sought to minimize common method bias. We investigated the potential impact of Learning orientation Performance-prove orientation Performance-avoid orientation Self-efficacy Proxy-efficacy Branch context service-sales ambidexterity Age⫹ Gender⫹⫹ Tenure⫹⫹⫹ Experience⫹⫹⫹ 5.66 5.13 3.53 4.85 5.78 31.84 34.30 2.43 1.63 54.53 111.35 0.93 1.16 1.46 1.06 1.24 9.54 9.84 0.98 0.48 55.80 87.11 Employee level Mean SD 5.67 5.15 3.55 4.86 5.82 32.00 34.49 2.50 1.61 55.48 116.03 0.47 0.57 0.71 0.54 0.74 5.53 5.46 0.34 0.19 28.62 39.05 Branch level Mean SD 2 0.50** ⫺0.08** 0.23** 0.58** 0.42** 0.38** 0.25** 0.53** 0.33** 0.66** 0.38** 0.08** 0.11** ⫺0.07** ⫺0.08** 0.01 0.06** 0.05* 0.09** 1 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ⫹⫹ 11 gender 0.01 ⫺0.05* 0.37** ⫺0.07** 0.50** 0.65** ⫺0.09** 0.52** 0.49** 0.61** 0.07** 0.23** 0.13** 0.08** 0.15** ⫺0.02 ⫺0.12** ⫺0.08** ⫺0.04 ⫺0.09** ⫺0.42** 0.06** 0.05** 0.04 0.01 0.05* 0.34** ⫺0.10** 0.08** 0.13** 0.09** 0.06** 0.09** 0.55** ⫺0.30** 0.41** 3 Notes: a Correlations are based on employee-level data (n ⫽ 2,306); ⫹ age consists of four categories, coded as “25 and below” ⫽ 1; “26 – 35” ⫽ 2; “36 – 45” ⫽ 3; “46 and above” ⫽ 4; is coded as male ⫽ 1, female ⫽ 2; ⫹⫹⫹ tenure and experience are calculated by months L; * p ⬍ 0.05; ** p ⬍ 0.01 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 No. Variable Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Service-sales ambidexterity 501 Table I. Means, standard deviations and correlationsa EJM 49,3/4 502 common method variance statistically, using multiple tests. We conducted an EFA with all manifest variables; Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first factor accounted for only 37.91 per cent of the variance. We also tested two measurement models, one with the focal constructs and one that also included a method factor (Paulraj et al., 2008). The method factor slightly improved model fit (increases of 0.01 in the adjusted goodness-of-fit index, normed fit index and confirmatory fit index). However, these slight improvements do not indicate that the results were inflated. Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Hypotheses testing We used hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to test H1-H5 (Raudenbush et al., 2004) and summarize the results in Table II. We first ran a null model including only the dependent Level and variable Intercept Individual-level control variables Age Gender Tenure Experience Branch-level control variables Branch size Branch location-city Branch location-suburban Individual-level antecedents Learning orientation Performance-prove orientation Performance-avoid orientation Self-efficacy Branch-level antecedents Branch context Null model (M1) 34.502** With individual-and branch-level predictors (M2) 34.479** 34.480** 0.513** 0.080 0.001 0.002 0.472** 0.098 0.001 0.002 ⫺0.356 ⫺1.071* ⫺1.518** ⫺0.357 ⫺1.070* ⫺1.518** 5.171** (H1a) 0.182 (H1b) –0.372** (H1c) 1.308** (H2) 5.383** 0.163 –0.369** 1.216** 0.703** (H5) 6.354** Cross-level interactions: individual-level antecedents ⫻ proxy efficacy Learning orientation ⫻ proxy efficacy Performance-prove orientation ⫻ proxy efficacy Performance-avoid orientation ⫻ proxy efficacy Self-efficacy ⫻ proxy efficacy n (Individual-level) 2,306 2,306 n (Branch-level) 267 267 16,852.33 15,647.185 Model deviancea Table II. Hierarchical linear modeling results With interaction terms (M3) 0.877** (H3a) 0.158 (H3b) –0.027 (H3c) –0.606** (H4) 2,306 267 15,637.212 Notes: * p ⬍ 0.05 (one-tailed); ** p ⬍ 0.01 (one-tailed); a deviance can be used as a measure of model fit: smaller deviance implies better model fit (Liao and Chuang, 2007) Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) variables. To test H1, H2 and H5, we added branch- and individual-level predictors. To test H3 and H4, we added interaction terms for proxy efficacy with each individual-level variable in the model. We used the group centering method for Level-1 variables to avoid the potential confound between a cross-level interaction and a between-group interaction (Hofmann and Gavin, 1998). To test H6, we aggregated service-sales ambidexterity to the branch level and performed a multiple regression analysis, such that we could test the relationship between service-sales ambidexterity and branch performance (de Jong et al., 2005). Null model. Table II contains the results of the null model (M1). We also calculated ICC (1) for service-sales ambidexterity, to illustrate the significant between-branch variance. The ICC (1) for service-sales ambidexterity was 0.30, such that 30 per cent of the variance in employees’ perceptions of service-sales ambidexterity resided between branches, and 70 per cent resided within branches. Therefore, the use of HLM analysis was appropriate in this case (Marrone et al., 2007). Adding individual- and branch context-level predictors: H1, H2 and H5. To test our prediction that goal orientation and self-efficacy are significantly associated with service-sales ambidexterity, we added goal orientation, self-efficacy, and branch context (performance management ⫻ social support). As we show in Table II (M2), we found a positive relationship of learning orientation (H1a ␥ ⫽ 5.171, p ⬍ 0.01) and a negative link of performance-avoid orientation (H1c ␥ ⫽ ⫺0.372, p ⬍ 0.01) with service-sales ambidexterity. However, we found no significant relationship between a performance-prove orientation and service-sales ambidexterity. Thus, H1 received only partial support. We also confirmed H2 because in Table II (M2), we find a positive relationship between self-efficacy and service-sales ambidexterity (␥ ⫽ 1.308, p ⬍ 0.01). Finally, we predicted a positive joint impact of performance management and social support on services–sales ambidexterity at the work unit (branch) level, and the results accordingly provided significant support for H5 (␥ ⫽ 0.703, p ⬍ 0.01). Adding cross-level interaction terms: H3 and H4. Regarding the potential moderating role of proxy efficacy, to test H3 and H4, we generated four cross-level interaction terms. The results appear in Table II (M3). We found support for H3a (␥ ⫽ 0.897, p ⬍ 0.01) and H4 (␥ ⫽ ⫺0.587, p ⬍ 0.01) but not for H3b or H3c. service-sales ambidexterity and branch performance: H6. Finally, we aggregated employee-level perceptions of service-sales ambidexterity to the branch level and performed a multiple regression analysis to uncover any positive relationship between them. We included branch size and branch location as control variables. The results indicated a significant positive relationship between service-sales ambidexterity and branch performance (F ⫽ 11.39, R2 ⫽ 0.148, p ⬍ 0.01); it explained 14.8 per cent of the variance in branch performance, in support of H6. Discussion We examine the service-sales ambidexterity issues raised in frontline service units by adopting a motivation and capability paradigm, which enables us to explore the impact of individual heterogeneity on a branch’s ability to be service-sales ambidextrous. Our study is among the first to address this challenge by considering both individual and branch contextual factors. Proxy efficacy, or confidence in the operational manager, exerts an interesting influence on the relationships between employee characteristics and ambidexterity performance. Confidence in this ability enhances the impact of an Service-sales ambidexterity 503 EJM 49,3/4 Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) 504 FLE’s learning orientation on service-sales ambidexterity, mainly due to the manager’s ability to lead by example, facilitate knowledge sharing and provide advice. Conversely, our data reveal that an FLE’s confidence in her or his own ability to sell may decrease when a supervisor displays greater ability and takes over the process. A manager who tends to dominate training and the sales process thus reduces opportunities for the FLE to build her or his own skill set. This limitation then prompts FLEs to relinquish some control if it is the easiest path to take; it even might demotivate them from learning new required skills. In these circumstances, the intervention of a proxy efficacy agent means that the FLEs’ self-confidence has a diminished impact on ambidexterity performance. Contextual factors offer important predictors of service-sales ambidexterity; we thus find support for prior theoretical findings in a specific, service-sales context. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the impact of these factors is complemented by FLE’s motivation and ability. The inclusion of proxy efficacy as a branch-level moderator also enhances understanding of the nature of these influential factors. Employees’ selling motivation and ability are associated with service-sales ambidexterity, but not all goal orientations have equivalent impacts. For example, FLEs’ learning orientation exerts a positive influence on service-sales ambidexterity, but the impact of the performance-avoid goal orientation is negative, and the performance-prove orientation seems to exert no influence at all. These findings match previous, inconsistent results regarding the relationship between salespeople’s goal orientation and performance (Ahearne et al., 2010). Blending familiar activities (i.e. service provision) with unfamiliar ones (e.g. selling) may diminish FLEs’ need to show that they can do well. Some FLEs actively try to avoid selling because they were not hired to perform such tasks. The positive association of self-efficacy with service-sales ambidexterity is consistent with previous studies that have argued that highly self-efficacious people display flexibility and persistence, which instigates a willingness to experiment by infusing service delivery with selling attempts. A key issue in pursing service-sales ambidexterity is resource constraints (March, 1991). The adoption of a flexible and persistent attitude helps FLEs deal with the apparently conflicting demands of these two types of activity. Finally, we confirm that service-sales ambidexterity is positively associated with branch performance. If a branch can successfully pursue both service and sales goals, its performance improves. This finding encourages a firm to pursue a dual emphasis service-sales strategy. Managerial implications Our findings offer significant managerial implications for retail banking branch managers who face service delivery– cross-selling tensions. A learning orientation is important, and branch managers should foster a climate that encourages the acquisition of new knowledge and skills, such as by providing FLEs with information, relevant training and exposure to internal and external experts. Learning efforts also need to be recognized, evaluated and rewarded. However, because staff members with strong performance-avoid orientations are likely to withdraw from challenging tasks, such as the simultaneous pursuit of service and sales goals, branch managers need external mechanisms to motivate these staff. For example, designated rewards might encourage them to take on challenging tasks (Fry, 2003). Alternatively, branch managers who assign tasks might give performance-avoid-oriented employees more simple, routine jobs rather than difficult and challenging tasks. In ambidextrous environments, branch Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) managers should also consider ways to release such employees and attract “new blood” if an ambidextrous environment is really a priority. Although adding a sales focus to a service unit is not a recent phenomenon (Burton, 1991), many employees continue to have difficulty dealing with the associated complexity. Self-efficacy is a dynamic construct that can change over time and improve through training (Gist and Mitchell, 1992). If the overall level of self-efficacy is low, branch managers should develop training programs to enhance it; continuous training support is necessary. Such programs require some caution though because branch managers’ efforts to assist and coach FLEs could have negative impacts on ambidextrous performance overall. Coaching FLEs who already have high levels of confidence seems likely to backfire and diminish their confidence. Instead, branch managers could grant more freedom and power to self-efficacious staff. In general, branch managers must be aware of the needs of their staff, improve communication skills and help them be more sensitive and empathetic, especially when training FLEs who already possess confidence in their ability to sell. The findings thus have direct implications for retail banking branch managers, but the implications also may be relevant to other service firms with multiple branches that simultaneously pursue service and sales targets, such as travel agencies, telecommunication providers and insurance. In these settings, FLEs face a similar dilemma when they must perform service and sales-related tasks simultaneously, with limited resources. Research implications Some limitations of our approach suggest directions for ongoing research. First, as we noted, FLEs empowered to deal with service-sales ambidexterity may suffer increased workload perceptions that hinder their service performance (Chan and Lam, 2011). Our surveys did not include a measure of workload or perceived workload, but further research that integrates this control variable could be insightful. Second, a longitudinal research design could better reveal whether self-efficacy loses significance for predicting performance over time (Vancouver et al., 2001). In general, longitudinal research could clarify the long-term impacts of service-sales ambidexterity on performance and the possibility of reciprocal effects (Lubatkin et al., 2006), resulting in a more comprehensive view. Third, simultaneity conceptually distinguishes organizational ambidexterity from dynamic capability (Kortmann, 2012). Similar to previous ambidexterity studies, we assumed that our operationalization of service-sales ambidexterity implicitly featured a simultaneity aspect, but this assumption has been questioned (Good and Michel, 2013). Therefore, investigations should include simultaneity in their operationalizations of ambidexterity. Fourth, the data for our independent and dependent variables came from the same source, which may create some common method bias. Most ambidexterity studies similarly rely on self-reported, survey data (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004), but we call on further research to collect objective ambidexterity data, such as objective indicators of service-sales ambidexterity that explicitly acknowledge simultaneity characteristics. Fifth, our assessment of proxy efficacy in relation to ambidexterity remains preliminary and offers a starting point for further inquiry. The diverging interaction effects with employee goal orientation and self-efficacy might reflect our Service-sales ambidexterity 505 EJM 49,3/4 Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) 506 operationalization of proxy efficacy, as employees’ confidence in their operational manager’s ability to sell in a service delivery context. Perhaps the emphasis should shift to capture the ability of a proxy to teach and communicate. Bandura (1997) asserts that proxy agents can help manage and coordinate the factors necessary for goal attainment; we hope that additional research incorporates an operationalization of proxy efficacy that reflects this assistance aspect and tests the robustness of the interaction effects that we encountered. Sixth, further research should determine if our proxy efficacy findings hold across contexts that vary in the extent to which they are proxy led (e.g. self-management teams) or proxy close (e.g. employees work in close contact with their supervisor or autonomously). Our research referred to an individual employee context, so these findings should be extended to include perceptions of collective agency too (i.e. team efficacy). More research is needed to examine broader ranges of individual characteristics and organizational factors that might drive service-sales ambidexterity. In our study context, the sales function was only recently added; studies modeling successful service-sales ambidexterity could refer instead to industries in which the twin goals have been an industry norm for some time. References Ahearne, M., Lam, S.K., Mathieu, J.E. and Bolander, W. (2010), “Why are some salespeople better at adapting to organizational change?”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 74 No. 3, pp. 65-79. Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J. and Rapp, A. (2005), “To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 90 No. 5, pp. 945-955. Aksin, O.Z., Armony, M. and Mehrotra, V. (2007), “The modern call center: a multi-disciplinary perspective on operations management research”, Production and Operations Management, Vol. 16 No. 6, pp. 665-688. Aksin, O.Z. and Harker, P.T. (1999), “To sell or not to sell: determining the tradeoffs between service and sales in retail banking phone centers”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 19-33. Bandura, A. (1997), Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control, W.H. Freeman, New York, NY. Bandura, A. (2001), “Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective”, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 52 No. 1, pp. 1-26. Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G.V. and Pastorelli, C. (1996), “Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning”, Child Development, Vol. 67 No. 3, pp. 1206-1222. Bliese, P.D. (2000), “Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: implications for data aggregation and analysis”, in Klein, K.J. and Kozlowski, S.W.J. (Eds), Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organization, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, pp. 349-381. Bray, S.R., Gyurcsik, N.C., Culos-Reed, S.N., Dawson, K.A. and Martin, K.A. (2001), “An exploratory investigation of the relationship between proxy efficacy, self-efficacy and exercise attendance”, Journal of Health Psychology, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 425-434. Bray, S.R., Gyurcsik, N.C., Ginis, K.A.M. and Culos-Reed, S.N. (2004), “The proxy efficacy exercise questionnaire: development of an instrument to assess female exercisers’ proxy efficacy beliefs in structured group exercise classes”, Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 442-456. Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Brett, J.F. and Vandewalle, D. (1999), “Goal orientation and goal content as predictors of performance in a training program”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 84 No. 6, pp. 863-873. Burton, D. (1991), “Tellers into sellers?” International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 9 No. 6, pp. 25-29. Button, S.B., Mathieu, J.E. and Zajac, D.M. (1996), “Goal orientation in organizational research: a conceptual and empirical foundation”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 67 No. 1, pp. 26-48. Byrne, B.M. (2001), Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, London. Cao, Q., Gedajlovic, E. and Zhang, H. (2009), “Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects”, Organization Science, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 781-796. Chan, K. and Lam, W. (2011), “The trade-off of servicing empowerment on employees’ service performance: examining the underlying motivation and workload mechanisms”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 39 No. 4, pp. 609-628. Christensen, A.J., Wiebe, J.S., Benotsch, E. and Lawton, W. (1996), “Perceived health competence, health locus of control, and patient adherence in renal dialysis”, Cognitive Therapy & Research, Vol. 20 No. 4, pp. 411-421. Covington, M.V. (2000), “Goal theory, motivation, and school achievement: an integrative review”, Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 51 No. 1, pp. 171-200. Crant, M.J. (2000), “Proactive behavior in organizations”, Journal of Management, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp. 435-462. Dart, J. (2009), “Bank workers forced to push loans to public”, Sydney Morning Herald, 1 February, Sydney. de Jong, A., de Ruyter, K. and Wetzels, M. (2005), “Antecedents and consequences of group potency: a study of self-managing service teams”, Management Science, Vol. 51 No. 11, pp. 1610-1625. Diessner, R., Solom, R.D., Frost, N.K., Parsons, L. and Davidson, J. (2008), “Engagement with beauty: appreciating natural, artistic, and moral beauty”, Journal of Psychology, Vol. 142 No. 3, pp. 303-332. Dixon, M.A. and Cunningham, G.B. (2006), “Data aggregation in multilevel analysis: a review of conceptual and statistical issues”, Measurement in Physical Education & Exercise Science, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 85-107. Eichfeld, A., Morse, T.D. and Scott, K.W. (2006), “Using call centers to boost revenue”, McKinsey Quarterly, Washington. Elias, S.M. and MacDonald, S. (2007), “Using past performance, proxy efficacy, and academic self-efficacy to predict college performance”, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 37 No. 11, pp. 2518-2531. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50. Fry, L.W. (2003), “Toward a theory of spiritual leadership”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 14 No. 6, pp. 693-727. Gelade, C.A. and Young, S. (2005), “Test of a service profit chain model in the retail banking sector”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 78 No. 1, pp. 1-22. Service-sales ambidexterity 507 EJM 49,3/4 Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) 508 Gibson, C.B. and Birkinshaw, J. (2004), “The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47 No. 2, pp. 209-226. Gist, M.E. and Mitchell, T.R. (1992), “Self-efficacy: a theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 183-211. Glick, W.H. (1985), “Conceptualizing and measuring organizational and psychological climate: pitfalls in multilevel research”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 601-616. Good, D. and Michel, E.J. (2013), “Individual ambidexterity: exploring and exploiting in dynamic contexts”, Journal of Psychology, Vol. 147 No. 5, pp. 435-453. Gupta, A.K., Smith, K.G. and Shalley, C.E. (2006), “The interplay between exploration and exploitation”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 49 No. 4, pp. 693-706. He, Z.L. and Wong, P.K. (2004), “Exploration vs. exploitation: an empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis”, Organization Science, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 481-494. Hofmann, D.A. and Gavin, M.B. (1998), “Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: implications for research in organizations”, Journal of Management, Vol. 24 No. 5, pp. 623-641. James, L.R. (1982), “Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 67 No. 2, pp. 219-229. James, L.R., Demaree, R.G. and Wolf, G. (1993), “r-sub(wg): an assessment of within-group interrater agreement”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 78 No. 2, pp. 306-309. Jasmand, C., Blazevic, V. and de Ruyter, K. (2012), “Generating sales while providing service: a study of customer service representatives’ ambidextrous behavior”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 76 No. 1, pp. 20-37. Kortmann, S. (2012), The Relationship Between Organizational Structure and Organizational Ambidexterity: A Comparison Between Manufacturing and Service Firms, Springer Gabler, Munster. Liao, H. and Chuang, A. (2007), “Transforming service employees and climate: a multilevel, multisource examination of transformational leadership in building long-term service relationships”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 92 No. 4, pp. 1006-1019. Lubatkin, M.H., Simsek, Z., Ling, Y. and Veiga, J.F. (2006), “Ambidexterity and performance in small- to medium-sized firms: the pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration”, Journal of Management, Vol. 32 No. 5, pp. 646-672. Lüdtke, O., Marsh, H.W., Robitzsch, A., Trautwein, U., Asparouhov, T. and Muthén, B. (2008), “The multilevel latent covariate model: a new, more reliable approach to group-level effects in contextual studies”, Psychological Methods, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 203-229. March, J.G. (1991), “Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning”, Organization Science, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 71-87. Marrone, J.A., Tesluk, P.E. and Carson, J.B. (2007), “A multilevel investigation of antecedents and consequences of team member boundary-spanning behavior”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50 No. 6, pp. 1423-1439. Marsh, H.W., Hau, K.T. and Wen, Z. (2004), “In search of golden rules: comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings”, Structural Equation Modeling, Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 320-341. Mittal, V., Anderson, E.W., Sayrak, A. and Tadikamalla, P. (2005), “Dual emphasis and the long-term financial impact of customer satisfaction”, Marketing Science, Vol. 24 No. 4, pp. 544-555. Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Netemeyer, R.G., Bearden, W.O. and Sharma, S. (2003), Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. Nunnally, J.C. and Bernstein, I.H. (1994), Psychometric Theory, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Paulraj, A., Lado, A.A. and Chen, I.J. (2008), “Inter-organizational communication as a relational competency: antecedents and performance outcomes in collaborative buyer-supplier relationships”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 45-64. Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., MacKenzie, Lee, J.Y. and Podaskoff, N.P. (2003), “Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88 No. 5, pp. 879-903. Raudenbush, S.W., Bryk, A.S., Cheong, Y.F., Congdon, R.T. and du Toit, M. (2004), HLM6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling, Scientific Software International, Lincolnwood, IL. Sackett, P.R., Gruys, M.L. and Ellingson, J.E. (1998), “Ability-personality interactions when predicting job performance”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 83 No. 4, pp. 545-556. Simsek, Z., Heavey, C., Veiga, J.F. and Souder, D. (2009), “A typology for aligning organizational ambidexterity’s conceptualizations, antecedents, and outcomes”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 46 No. 5, pp. 864-894. Sosik, J.J., Godshalk, V.M. and Yammarino, F.J. (2004), “Transformational leadership, learning goal orientation, and expectations for career success in mentor-protégé relationships: a multiple levels of analysis perspective”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 241-261. Sparacino, J. (2005), “Cross-selling made easy: first, ensure that all of your employees know the bank’s products inside out. Then, train them to ask basic questions about customer needs”, ABA Bank Marketing, October, available at: www.questia.com/library/1G1-175181372/ cross-selling-made-easy-first-ensure-that-all-of (accessed 7 February 2011). Sujan, H., Weitz, B.A. and Kumar, N. (1994), “Learning orientation, working smart, and effective selling”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58 No. 3, pp. 39-52. Vancouver, J.B., Thompson, C.M. and Williams, A.A. (2001), “The changing signs in the relationships among self-efficacy, personal goals, and performance”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86 No. 4, pp. 605-620. Vandewalle, D. (1997), “Development and validation of a work domain goal orientation instrument”, Educational and Psychological Measurement, Vol. 57 No. 6, pp. 995-1015. Vandewalle, D., Brown, S.P., Cron, W.L. and Slocum, J.W. Jr (1999), “The influence of goal orientation and self-regulation tactics on sales performance: a longitudinal field test”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 84 No. 2, pp. 249-258. Wells Fargo (2011), “News release: wells Fargo reports record quarterly and full year net income, January 19”, available at: www.wellsfargo.com/downloads/pdf/press/4q10pr.pdf (accessed 7 February 2011). Yaffe, T. and Kark, R. (2011), “Leading by example: the case of leader OCB”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 96 No. 4, pp. 806. Zeithaml, V.A. (2000), “Service quality, profitability, and the economic worth of customers: what we know and what we need to learn”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 67-85. Service-sales ambidexterity 509 EJM 49,3/4 Appendix Measures Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) 510 Table AI. Measures and measurement criteria Branch context Performance management Members of my team are responsible for deciding how to organize our work Members of my team are responsible for deciding how to achieve our goals Members of my team are responsible for determining the best way to satisfy our customers’ requirements Members of my team are empowered to make the day-to-day business decisions that enable us to be successful Members of my team are empowered to change our work processes in order to improve our performance The recognition and rewards employees receive for the delivery of superior work is high Social support In our branch, we help each other in serving our customers when needed In our branch we place a high value on the mutual support of team members In our branch, each team member is personally responsible for the assistance of other members in serving the customer In our branch, each team member is involved with what is going on in our team The job knowledge and skills of employees in our branch to deliver superior quality work and service is sufficient The leadership shown by management in our branch in supporting the service and sales effort is appropriate Goal orientation Learning orientation I am willing to select a challenging task that I can learn a lot from I often look for opportunities to develop new skills and knowledge I enjoy challenging and difficult tasks at work where I’ll learn new skills I prefer to work in situations that require a high level of ability and talent Performance-prove orientation I try to figure out what it takes to prove my ability to others at work I enjoy it when others at work are aware of how well I am doing I prefer to work on tasks where I can prove my ability to others Performance-avoid orientation I would avoid taking on a new task if there was a chance that I would appear rather incompetent to others Avoiding a show of low ability is more important to me than learning a new skill I prefer to avoid situations at work where I might perform poorly Self-efficacy I am good at selling I know the right thing to do in selling situations I am good at finding out what customers need It is easy for me to get customers to see my point of view Proxy efficacy Our branch manager has a clear understanding of where we are going Our branch manager is able to get others committed to his/her dream Our branch manager provides a good model for me to follow Our branch manager leads by example Loadings t-Value 0.87 0.90 28.02 28.53 0.88 28.18 0.79 26.67 0.73 25.51 ␣ AVE 0.91 0.60 0.88 0.53 0.89 0.68 0.85 0.66 0.78 0.55 0.83 0.54 0.93 0.78 0.54 0.66 23.78 0.85 27.27 0.85 27.30 0.83 27.01 0.58 26.68 0.53 0.85 0.86 0.86 0.72 38.98 39.47 39.27 0.72 0.84 0.86 37.01 43.48 0.82 26.43 0.78 0.61 26.31 0.78 0.73 0.75 0.69 32.05 30.47 31.11 0.94 0.96 0.87 0.76 49.56 67.27 91.55 (continued) Downloaded by University of New South Wales At 00:52 04 May 2015 (PT) Measures Service-sales ambidexterity Service In our branch, we increase the level of service quality delivered to customers In our branch, we constantly survey existing customers’ satisfaction In our branch, we fine tune what we offer to keep our customers satisfied In our branch, we continuously improve the reliability of our services Sales In our branch, we create new ways to expand client portfolios In our branch, we look for creative ways to increase the number of sales In our branch, we explore the sales potential of market segments In our branch, we actively target new customer groups In our branch, we penetrate more deeply into our existing customer base In our branch, we base our success on our ability to explore sales opportunities Loadings 0.76 0.70 0.75 0.79 0.91 0.80 0.81 0.77 0.83 0.76 t-Value ␣ AVE 0.89 0.70 32.80 30.50 32.34 511 0.62 33.89 34.53 33.20 35.01 32.84 0.67 Notes: Fit indices: goodness-of-fit index ⫽ 0.93; adjusted goodness-of-fit index ⫽ 0.91; root mean square error of approximation ⫽ 0.05; square root mean residual ⫽ 0.06; normed fit index ⫽ 0.94; confirmatory fit index ⫽ 0.95. About the authors Ting Yu is a lecturer in Marketing at the University of New South Wales. Her major research interests include organizational ambidexterity (service versus sales; efficiency versus flexibility), relationship termination management and consumer emotions. Her research has appeared in Journal of Service Research, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Services Marketing and Journal of Service Management/International Journal of Industry Management. Ting Yu is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: ting.yu@unsw.edu.au Paul G. Patterson is a Professor of Marketing in the Australian School of Business at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia. His research has been published in numerous leading journals, including Journal of Service Research, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Retailing, Journal of International Business Studies, International Journal of Research in Marketing, European Journal of Marketing and California Management Review. Ko de Ruyter is a Professor of Marketing at Maastricht University, The Netherlands. He has published six books and numerous scholarly articles in, among others, Journal of Marketing, Management Science, Journal of Consumer Research, Journal of Retailing, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Decision Sciences, Organization Science, Marketing Letters, Journal of Management Studies, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Economic Psychology, Journal of Service Research, Information and Management, European Journal of Marketing, and Accounting, Organisation and Society. For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com View publication stats Service-sales ambidexterity Table AI.